Network effects benefit larger companies and their customers. Whoever gets to scale first will have a substantial advantage. Building a network-effects business is a mad rush. But what about the companies that are left behind? What about small firms? Are there effective strategies for companies that have a limited number of customers? Yes! There are many examples of smaller companies that compete successfully with (and sometimes even displace) larger organizations that benefit from network effects. Some of the smaller firms succeed by creating customer delight that does not reflect scale. Others find success by giving preference to one of the groups on the platform. Serving a small set of customers can also lead to stellar performance. Let’s look at some examples that illustrate these three strategies.

Creating Customer Delight That Does Not Reflect Scale

We have already encountered this strategy. Remember how Taobao, once a small startup, battled eBay, then the dominant platform with an 85 percent share in the Chinese market? Taobao’s success is all the more surprising because platforms like eBay benefit from network effects. In fact, it was these network effects that made Meg Whitman, then CEO of eBay, so confident that she would win in China.

From Taobao’s perspective, the competitive situation must have looked daunting (figure 9-1). Having been the first to enter the market, eBay had attracted a much larger number of customers, and that drew many more stores to its platform. It is a classic network-effects story. How could Taobao possibly catch up? It did so by finding other ways to boost willingness-to-pay (WTP)! With the help of services such as Alipay and Wang Wang, and thanks to a superior website design and two-sided ratings, Taobao increased and eventually matched eBay’s ability to delight customers. The company caught up with and eventually surpassed eBay by developing crowd-pleasing features that work independent of scale.

Figure 9-1 Network effects and competitive advantage

As powerful as network effects can be, it is important to remember that WTP and customer delight are the currency that ultimately counts. In this sense, there is nothing magical about network effects.1 An increase in WTP that results from network effects is no more valuable than increases in WTP that reflect great ideas, a more pleasant customer experience, or less-expensive complements.

Favoring One Group on the Platform

October 8, 2015, was a dark day for Etsy, a prominent online marketplace for handcrafted goods. On that day, Amazon launched Handmade, which competed directly with Etsy’s business. “Amazon Launches Its Etsy Killer,” cried USA Today, and Etsy’s share price dropped 6 percent.2 Amazon’s advantage was plain to see: “Etsy … has reason to be worried,” explained CNBC’s Catherine Clifford. “While the company already has significant brand association with the artisanal maker movement, Amazon’s customer base—and potential exposure for makers—is much larger. Amazon has an estimated 285 million active buyers, while Etsy has just under 22 million.”3 Remember, in platform competition, scale wins.

Or does it? In the five years since Amazon’s entry, Etsy’s revenues have more than tripled and its share price has risen tenfold. One reason that Etsy and Handmade can live side by side is that their platforms favor different groups. Amazon is squarely in the customer’s corner. Every feature of its business is designed with customers in mind. By contrast, Etsy was set up to support artisans and serve the craft movement. This difference in orientation manifests itself in many ways. Etsy charges sellers lower fees and releases their payments immediately, while Amazon holds on to seller funds. Etsy has a long history of supporting the maker movement, engaging in extensive seller education and community support. When the company went public in 2015, it offered sellers a pre-IPO participation program. While Amazon insists on controlling communication and the interaction between sellers and their customers, artisans on Etsy can harvest customer contact information and add promotional materials in their shipments.4 Lela Barker, a seller on Etsy, explains the basic difference: “In the final equation, Etsy has raised a generation of savvy makers that Amazon can now monetize. While that’s a brilliant business move on Amazon’s behalf, the maker community isn’t any better for it…. I fear that handmade sellers are little more than dollar signs to Amazon.”5 Robin Romain, who sells her quirky, pet-lover clothes and accessories on both platforms, adds, “[Amazon] always sides with the customer and that can put handmade sellers in jeopardy, especially with customized offerings.”6

Platforms serve multiple groups of customers, and while many create value for all groups, some choices betray the organization’s primary orientation. A travel site that sorts hotels by profit margin primarily serves the lodging industry. A site that sorts by customer reviews has the opposite orientation. The distinction between buyer-focused and seller-dominated platforms is particularly stark in B2B. At one extreme, procurement platforms serve buyers by creating efficiencies in purchasing. At the other end of the spectrum, seller-oriented platforms often resemble business directories. Some platforms evolve over time. Alibaba, for example, started out being oriented toward sellers and became more buyer focused over time.7 In markets where buyer-oriented and seller-focused platforms compete, neither can afford to neglect the other’s prime group of customers entirely.8 Competing with Handmade, Etsy has become less seller oriented. It now mimics Amazon in some of its decisions—it offers free shipping, for example. Despite the greater similarities, however, a profound sense of difference remains.

If yours is a small company staring at a large platform, it is always worth asking whether you might be able to create meaningful differentiation by focusing on the WTP of the group that is less favored by your competitor. Etsy found success battling the superpower that is Amazon by doing exactly that—maintaining a sharp focus on the success of its sellers.

Serving a Small Set of Customers

In all likelihood, this is the most counterintuitive move that platforms make when they compete against larger rivals that benefit from network effects. How can you succeed against big by being small? Consider online dating as an example. With 35 million monthly visitors, Match.com is the leading dating site in the United States.9 It dwarfs competitors such as eharmony. And yet eharmony thrives. The company even manages to charge a price premium for access to a far smaller pool of dating prospects.10 This is all the more surprising because eharmony lacks basic services—the site has no search function, for instance—and it limits the number of potential dates its users can see on any given day. How is this a recipe for success?

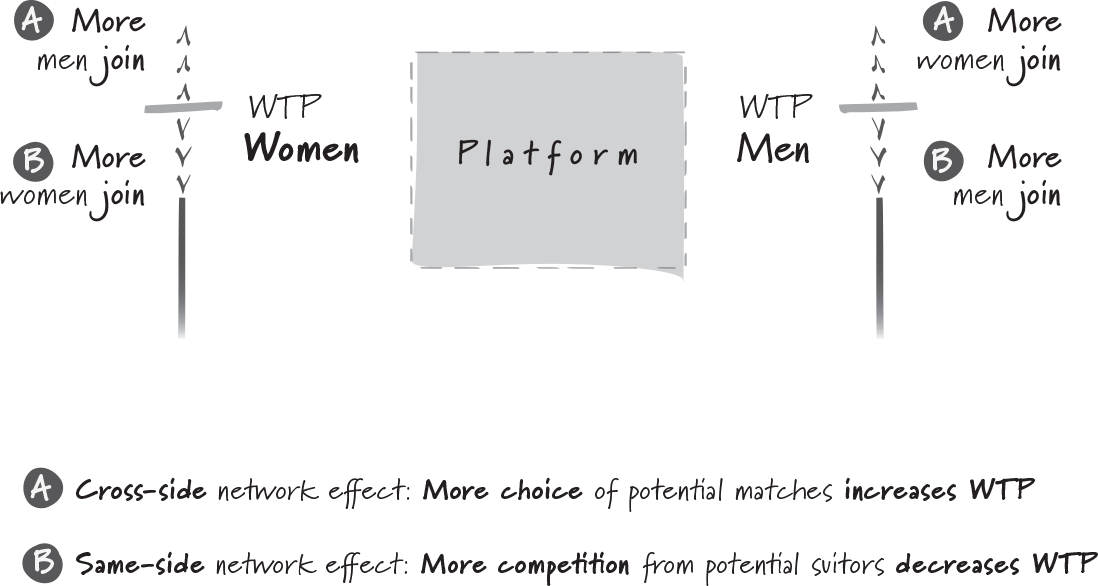

To understand eharmony, let’s think about what happens when a dating site begins attracting more customers. As its membership grows, WTP is pulled in opposite directions.11 For a man who would like to date a woman, WTP increases as more women join the site. This is the classic network effect. It is sometimes called a cross-side network effect because it describes the connections between different groups on the platform (figure 9-2). By contrast, the WTP of men who want to date women dwindles as more men join the site, because they now face greater competition. The “same-side network effect” is negative.

Figure 9-2 Same-side and cross-side network effects

A supersized site like Match.com presents millions of choices, and competition is fierce. Both effects are more moderate on smaller sites like eharmony. The balance of choice and competition helps daters choose their preferred site. Consider someone for whom finding a romantic partner is very important. This person is happiest in a committed relationship; being rejected is particularly painful. For this person, eharmony is the better choice because it keeps competition at bay by offering no search and giving a limited set of potential matches each day.

Now think of someone who is as happy in a relationship as they are outside one. Being rejected is still unpleasant, but it is less consequential. This person will look at eharmony and think, “Why would I pay a premium for fewer choices?” eharmony’s pricing policy is a factor that helps daters identify their preferred site. Those seeking committed relationships flock to eharmony, which further improves their experience on the site. Angela G’s account is typical: “I totally love eHarmony. I had no success on other sites like Match.com or Plenty of Fish, but on eHarmony I got … real results. They truly give you compatible people.”12 The key insight here is that every large platform serves many different types of customers. The attraction between the types varies, however, and building a smaller platform for individuals who greatly value one another is a promising strategy.

Failing to pay attention to differences in the mutual attraction of platform participants can have grave consequences. Do you remember Friendster, a social network that predated Facebook? Friendster was enormously popular. In fact, it was so successful that it was unable to serve everyone who wanted to sign up. It simply lacked the technical and financial capacity to keep up with its user growth. “Friendster was having a lot of technology problems,” remembers Jonathan Abrams, the company’s founder. “People could barely log into the website for two years.”13 To tackle this predicament, Friendster decided to register new users on a first-come, first-served basis—a big mistake, given that the site’s users were geographically dispersed. Friendster had many fans in North America, but it was also popular in Indonesia. Adding Indonesians to the network did not raise the WTP of most Americans, because they did not have Indonesian friends; and growing the US user base was meaningless for most Indonesians. By admitting new users first-come, first-served, Friendster diluted its network effects, and that added to its competitive woes. Compare Friendster with Facebook. The latter built powerful network effects by focusing initially on a single college and then on a select number of universities. Facebook ended up dominating the world precisely because it limited its growth early on, creating small communities whose members highly valued being connected with each other.

ShareChat, an Indian social network, applies that same strategy by offering its services in 14 local languages. “It becomes very difficult for the Indian netizens to search information in vernacular content,” explains cofounder and CEO Ankush Sachdeva. “Platforms like Quora or Reddit solved it for the English-speaking users, but nothing was available in an organized curated format in Indian languages.”14 With its focus on smaller local languages and content, Twitter-backed ShareChat attracts 160 million monthly active users, making it about as popular in India as Instagram.15

To strengthen the mutual attraction of smaller groups of customers, some companies cleverly segment their services. Istanbul’s MAC Athletic Club, for instance, offers three types of clubs. Top-tier members have the highest WTP for fitness, and they are charged a premium price for access to particularly attractive facilities. MAC also charges premium prices for personal trainers who seek to work with the company’s top-tier clients. The match—members and personal trainers who greatly value fitness—is attractive to both parties.

“Focus on a limited set of customers” is not the most intuitive advice if you are trying to build a business that will benefit from network effects. It is nevertheless good advice. By serving a select group of users who benefit most from being connected to one another, you might be able to compete with much bigger platforms.

In the early days of studying companies that benefit from network effects, many investors assumed these companies were poised to dominate their markets. Scaling quickly without any regard for profitability became the mantra.16 This approach is deeply flawed for two reasons. In chapter 8, we observed how geography often limits the power of network effects. In this chapter, we have seen that markets with network effects often remain competitive because small players find ways to persist.

- Underdogs lift WTP in ways that do not depend on scale. Network effects are one way to raise WTP, but there are many others. As long as these alternatives require no substantial investments, the smaller organization is not at a disadvantage in exploiting them.

- Underdogs cater to neglected parties. Most platforms favor specific groups—customers or vendors. Serving the unloved group allows for meaningful differentiation.

- Underdogs focus on a small group of customers who place a high value on connections with one another. The number of users, a common proxy for the strength of network effects, has always been a flawed metric. In practice, customers attach a different value to connections with different groups. The dominant platform boasts the largest number of users. But smaller companies can build businesses that emphasize high-value connections.