Few entrepreneurial careers illustrate the role of fortunate accidents (and accidental fortunes) as clearly as that of Stewart Butterfield, cofounder of Flickr and Slack. Butterfield’s first startup built a multiplayer online game whose main purpose was to “kick ass.” It largely failed to do so, but the tools created for developing the game provided the building blocks for Flickr, a photo-sharing site that Butterfield eventually sold to Yahoo! He later returned to gaming to produce Glitch, another failure—and another instance where software written for a project that failed proved generally useful: thus was born Slack. The workplace communication platform went public in 2019. A year later, it was valued at $15 billion.

In many ways, Slack exemplifies the mindset we have explored throughout this book. The company obsesses about customer willingness-to-pay (WTP) and talent willingness-to-sell (WTS). Slack works hard to escape a narrow product mindset. In a now-classic memo titled “We Don’t Sell Saddles Here,” Butterfield explains how a focus on WTP opens up business opportunities:

Consider the hypothetical Acme Saddle Company. They could just sell saddles, and if so, they’d probably be selling on the basis of things like the quality of the leather they use or the fancy adornments their saddles include.… Or, they could sell horseback riding. Being successful at selling horseback riding means they grow the market for their product while giving the perfect context for talking about their saddles.1

Because the company espouses a broad notion of value creation, Slack seems novel and unique to many of its customers, which is interesting because it is not. Similar products existed before Slack, but Yammer, HipChat, and Campfire failed to catch on because clients found it difficult to see how group messaging would create value. Butterfield describes the process of developing a deep understanding of customer WTP.

Just as much as our job is to build something genuinely useful, something which really does make people’s working lives simpler, more pleasant and more productive, our job is also to understand what people think they want and then translate the value of Slack into their terms.… Putting yourself in the mind of someone who is coming to Slack for the first time—especially a real someone, who is being made to try this thing by their boss, who is already a bit hangry because they didn’t have time for breakfast, and who is anxious about finishing off a project before they take off for the long weekend—putting yourself in their mind means looking at Slack the way you look at some random piece of software in which you have no investment and no special interest.2

For a company that is as obsessed with WTP as Slack is, Butterfield and his team made a counterintuitive decision when they first developed the communication platform. Rather than developing an all-around well-working product, they expended all their energy on only three features—search, synchronization across devices, and file sharing—at the expense of many other desirable functions. Why would a company that genuinely cares about customer WTP adopt a shortcut? Why not do it properly? Why not do it all? The notion that a focus on WTP (or WTS) implies doing it all, getting better by every conceivable measure, is perhaps the single biggest risk of adopting a strategy that is centered entirely on value creation. Invariably, companies that attempt to do it all fail to create significant value, because every value proposition reflects a set of trade-offs, a mixture of dos and don’ts, a blend of promises and letdowns.

Slack’s decision to focus on only three features is an example of such a trade-off. Slack is what my colleague Professor Youngme Moon, in her elegant book on differentiation, calls a reverse-positioned brand.3 These brands choose to be bare-bones in many respects, only to surprise us with extravagance in others. IKEA, JetBlue, the early Toyota Corolla, and Slack have all assumed reverse positions.

Resource constraints are the main reason firms assume reverse positions. To be great in one specific dimension—search, for example—Slack had to neglect many others. This principle holds true not only for startups, where resource constraints are particularly severe. Excellence invariably requires resources in short supply: time, capital, managerial attention. Investing these resources in one place (so as to be outstanding) means they will not be available elsewhere. Companies that spread their resources over many product attributes and innumerable service features end up being mediocre throughout, because they lack the means to be truly excellent. As my colleague Professor Frances Frei and Anne Morriss write in their analysis of companies that provide uncommon service quality, “You must be bad in the service of good.”4

The logic of trade-offs is impeccable and not difficult to understand. “We had a lot of conversations about choosing the three things we’d try to be extremely, surprisingly good at,” says Butterfield. “And ultimately we developed Slack around really valuing those three things. It can sound simple, but narrowing the field can make big challenges and big gains for your company feel manageable. Suddenly you’re ahead of the game because you’re the best at the things that really impact your users.”

Making Trade-Offs Visible

In many executive education courses at Harvard Business School, we conduct what we call a value map exercise. Of all the hands-on tasks with which we engage our course participants, this is one of our most impactful activities. We must have run this exercise with hundreds of companies. It leaves a deep impression every time.

You begin to build a value map by selecting a group of customers—or a group of employees if you create a map for talent. Next, you compile a list of criteria that are important to these customers when they make a purchase. These criteria are called value drivers (figure 17-1). Think of them as the product and service attributes that determine WTP (or WTS).

Figure 17-1 Value drivers

You then rank the value drivers from most important to least important. For example, your customers might value speed of service above all else. In this case, “speed” is value driver number one. If your customers do not care much about the price of your service, “price” goes toward the bottom of the list. Keep in mind that this is the customer’s perspective, not yours. In a final step, indicate for each value driver how good your company is at meeting this customer demand. For instance, “speed” could be important for your customers, but your company might be mediocre at providing fast service.5

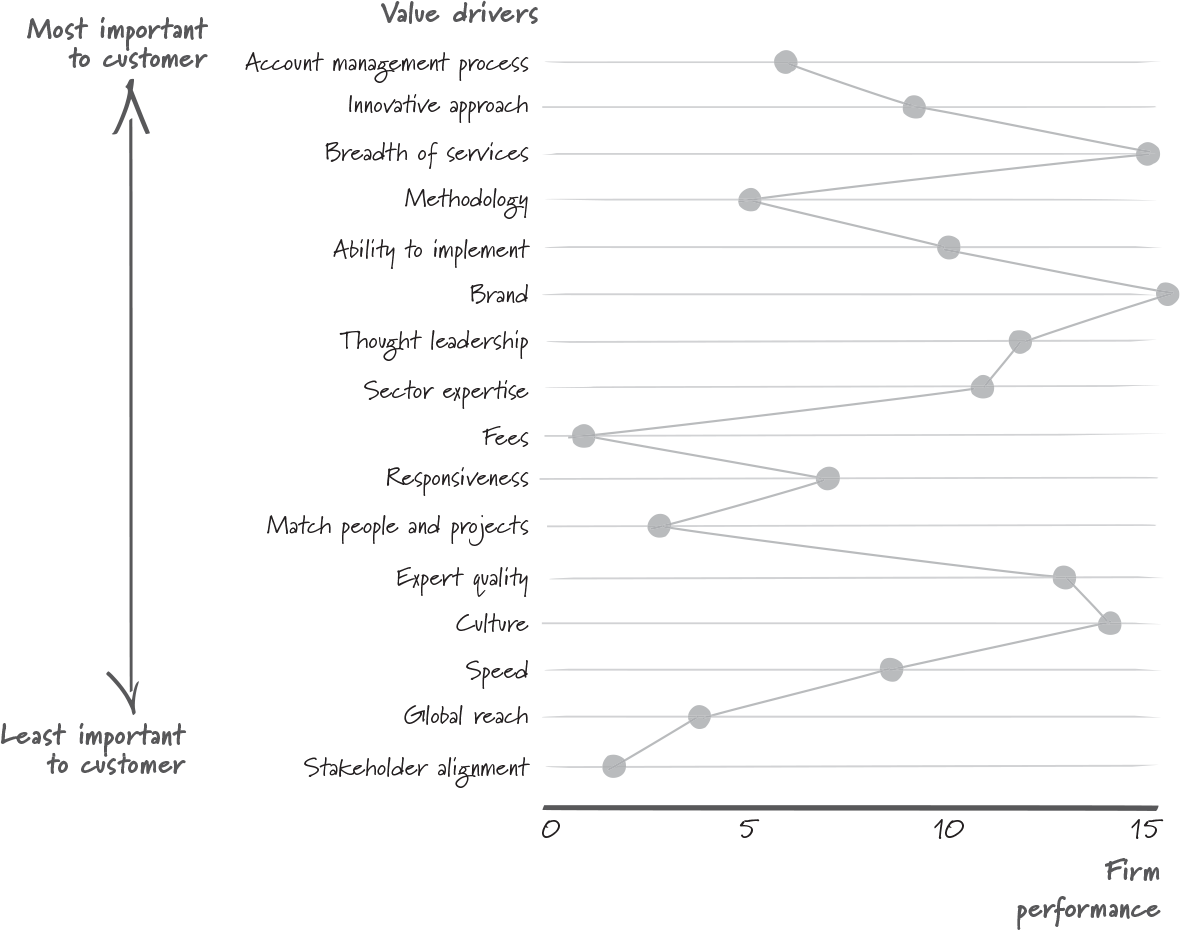

Value maps allow you to see, at a glance, your competitive standing and strategic opportunities.6 Figure 17-2 shows an example of a global consulting company, one of the so-called Big Four firms. This value map is based on interviews conducted by Source Global Research, a firm based in London. To establish the list of value drivers and rank them, Source speaks annually with over 3,000 executives about their recent experience with consulting engagements.

Figure 17-2 Value map for a global consulting firm

As you can see in figure 17-2, the firm’s clients care most about how well their account is managed and the firm’s innovation capabilities. These are the top two value drivers. Global reach and stakeholder management are less critical. The figure also shows that the firm’s value proposition is not particularly well aligned with the clients’ WTP. The firm underperforms on some important service attributes (e.g., innovation), and it exceeds expectations in areas of little importance to clients (e.g., culture). Fiona Czerniawska, cofounder and joint managing director of Source, was not surprised by these results.

Most consultants have a very strong sense of client service; they are genuinely trying to do what clients want. But they don’t really know what their clients want. And their tendency is to deliver what they think the client needs. They are not trained to have a good conversation about it in practice. When a client asks for a proposal, consultants talk about their work, but they don’t say, “Why are we here then? Why don’t you do this yourselves? What are we supposed to bring that is of value to you?” And that means it’s not embedded in the proposal, which means that people working on the project don’t really understand why they are there.7

The consulting industry is no exception. Many value maps resemble the one shown here. If the value drivers are appropriately ordered from most important to least important, an ideal value curve—the line that connects the levels of performance for each value driver—would tend to slant from top right to bottom left. Firms exceed expectations where it counts, and they sustain excellence by diverting resources from lower-ranked value drivers. Why not be excellent on all dimensions? Trade-offs. The slanted value curve reflects the trade-offs that are necessary to deliver stellar services.

Executive Ambition Meets Trade-Offs

When I conduct this exercise at Harvard Business School, we discuss the importance of trade-offs before the executives create value maps for their own firms. It is usually a short conversation. Everyone agrees that companies cannot be good at everything; true excellence requires firms to shift resources from value drivers of lesser importance to critical customer concerns that drive WTP.

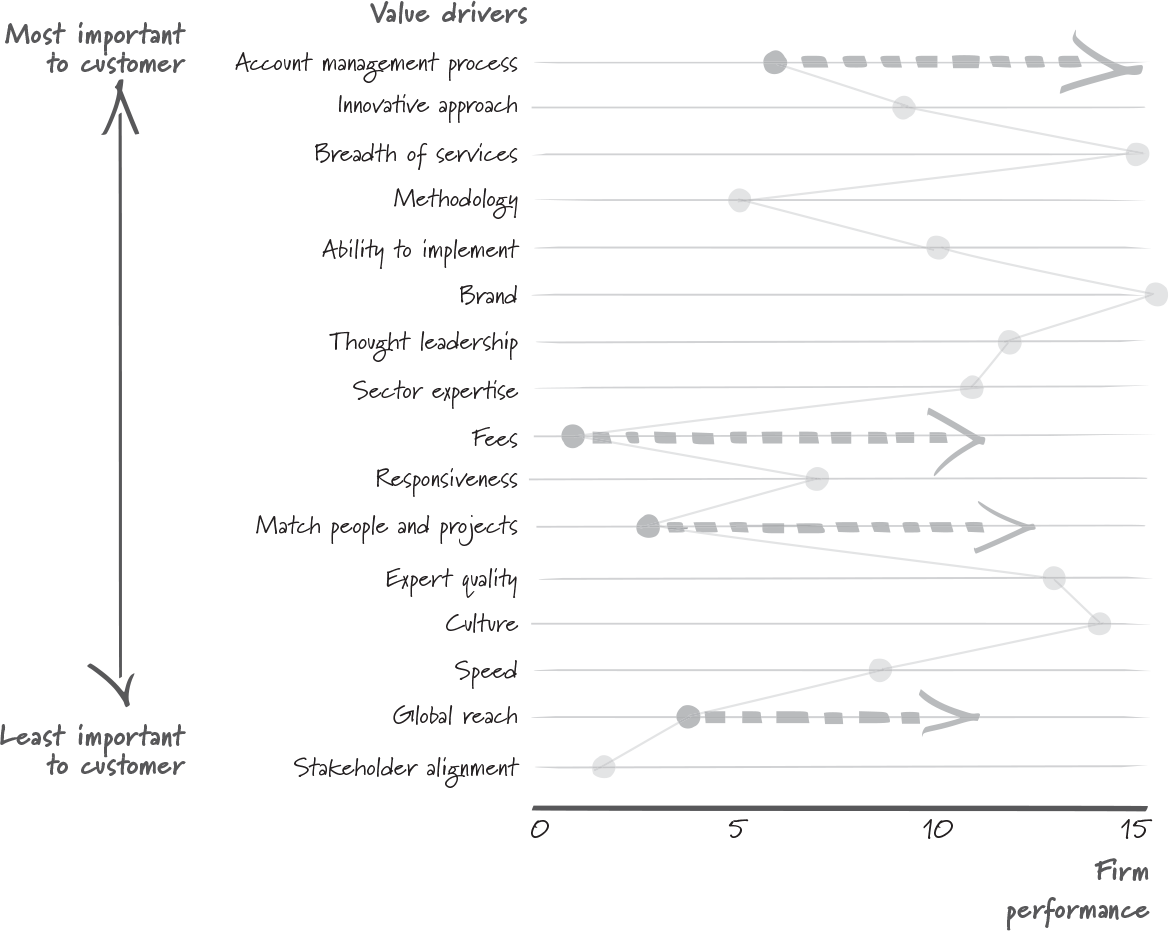

When the course participants complete their maps, I ask them to use arrows to indicate how they would like to evolve their firm’s value proposition over time (figure 17-3). Can you guess the results?

Figure 17-3 Improving the global consulting firm’s value proposition

All the arrows point to the right! A good hour after we have all agreed on the importance of trade-offs for business success, there are often few trade-offs in sight. Smart, ambitious executives want to become better at everything. Does this remind you of your firm? Do you sit in meetings where you make long lists of products and processes to improve? The sad news is, of course, that any attempt to get better at everything virtually guarantees mediocrity—exhausted mediocrity at that. By spreading scarce resources across many value drivers, you make it impossible for your organization to achieve true excellence.

I have been thinking about why it is so difficult to make trade-offs. Why is it challenging to decide what not to do? Where not to invest? Where to underperform? Here is one conjecture: the idea of trade-offs applies least to incredibly talented, supersmart people, the type I encounter in C-suites and in HBS executive education programs. These folks can be good at almost everything. And if they sacrifice a little sleep, they get huge amounts of work done, just in time and in fabulous quality. The danger is to take this model of personal success and apply it to organizations. (Some) people can be good at almost everything, but companies cannot. Firms must pick and choose where they strive for excellence lest they be condemned to remaining second-rate.

The lessons here are straightforward.

- Value maps are a simple tool that provide a wealth of information. They reveal the product and service attributes that determine customer WTP; they show where you have an advantage in creating customer delight and where you lag; and, perhaps most importantly, they indicate if your firm is making appropriate trade-offs. Do you excel where it counts?

- It is exciting to decide where to excel and figure out how to make progress. It is far harder, however, to determine where not to invest, where to underperform. True excellence is built on trade-offs. No company can be good at everything.

- The next time you and your team sit in a strategy meeting and you start making a long list of issues to resolve, projects to complete, and services to improve, remember to ask, “What will we stop doing?”