In the past few decades, strategy has become increasingly sophisticated. If you work for a sizable organization, chances are your company has a marketing strategy (to track and shape consumer tastes), a corporate strategy (to benefit from synergies), a global strategy (to capture worldwide business opportunities), an innovation strategy (to pull ahead of the competition), an intellectual property strategy (to defend the spoils of innovation), a digital strategy (to exploit the internet), a social strategy (to interact with communities online), and a talent strategy (to attract individuals with extraordinary skills). And in each of these domains, talented people work on long lists of urgent initiatives.

Companies are right, of course, to consider all these challenges. Rapid technological change, global competition, supply chain disruptions due to climate change and worldwide health emergencies, as well as ever-evolving consumer tastes, do conspire to upend traditional ways of doing business. As the world’s economies became more integrated, firms needed a global strategy. As technology altered consumer tastes and ways to satisfy them, it was imperative to rethink innovation and marketing. As the cost and utter unfairness of limiting workplace diversity became impossible to ignore, companies needed to find ways to build more inclusive talent pools and career paths. By responding to each of the new challenges, however, we asked ever more of our organizations, had even higher expectations of employees, and required our complex strategies to bring about sheer miracles.

I see evidence of such increased expectations everywhere. They manifest themselves in outstanding products, unbelievable experiences, and “deals of a lifetime”—but also in long working hours, seemingly impossible stretch goals, and harried lives. When I visit companies to do research and write cases, I rarely leave without being impressed by how much people accomplish in short periods of time, often with limited resources. But here is what surprises me most: given the sophistication of firm strategies and the intensity of our work lives, I would expect to see impressive firm profitability at most companies and more-than-generous compensation packages for nearly everyone. I see neither. Take firm profitability: one-fourth of the firms included in the S&P 500 fail to earn long-term returns in excess of their cost of capital. In China, this fraction is even higher, closer to one-third.

Think about it. How can it be that so many companies, their ranks filled with talented and highly engaged employees, have so little to show for so much effort? Why do hard work and sophisticated strategy lead to enduring financial success for some companies but not for others? We have the most educated workforce in human history and incredibly talented corporate leaders. Why does enduring success so often seem elusive? If you’ve ever wondered about these questions, this book is for you.

When our companies fall short of expectations, we often suspect that we are missing some key ingredient. If only we had a better talent strategy. If only we had a more robust supply chain. If only we had a richer innovation pipeline. If only … And so we develop a talent strategy, invest in business resilience, accelerate innovation cycles. As our strategic initiatives multiply, something unforeseen happens. In concentrating on all the trees, we lose sight of the forest. In a profusion of activities, an overall direction, a guiding principle, is hard to see. Any promising idea is an idea that seems worth pursuing. In the end, common sense rules, and strategy loses much of its ability to steer our businesses. In this world, strategic planning becomes an annual ritual that feels bureaucratic and less than helpful in resolving critical issues. In fact, it is not difficult to find firms that have no strategy at all. In many others, it consists of an 80-page deck that is rich in data but short on insights, fabulous at listing considerations but of little help in actual decision-making.1 When I review companies’ strategic plans, I often see a plethora of frameworks—many of them inconsistent with each other—but few guideposts for effective management. If the hallmark of a great strategy is its telling you what not to do, what not to worry about, which developments to disregard, many of today’s efforts fall short.2

In this book, I argue that strategic management faces an attractive back-to-basics opportunity. By simplifying strategy, we can make it more powerful. By using an overarching, easy-to-grasp framework that is tied to financial success, we gain a common language that allows us to evaluate and pull together the many activities that take place in our organizations today.

I have seen the effect of simpler thinking in hundreds of executives I have taught at Harvard Business School. These managers were familiar with popular strategy frameworks, and their firms had often implemented laborious planning processes to guide investment decisions and managerial attention. Yet in many instances, it was difficult, even for these accomplished professionals, to recognize how specific projects were linked to their firm’s strategy. At best, strategy provided smart arguments for and against business propositions, but it offered little guidance on how to choose and where to focus. As a result, initiatives and activities proliferated. When no one knows when to say no, most ideas (brought forward by talented and ambitious employees) seem like good ideas. And when most ideas seem like good ideas, we end up in the hyperactivity that pervades the business world today.3

I honed my approach to strategy in response to the challenges that I observed in the classroom and in my capacity as an adviser to companies. In my experience, value-based strategy, the approach I describe in this book, is well suited to cutting through complexities and evaluating strategic initiatives. The framework provides a powerful tool that will allow you to see how your digital strategy is (or is not) related to your global ambitions, and how your marketing strategy is (or is not) consistent with the way you compete in the market for talent. Value-based strategy helps inform your decisions about where to focus and how to deepen your firm’s competitive advantage.

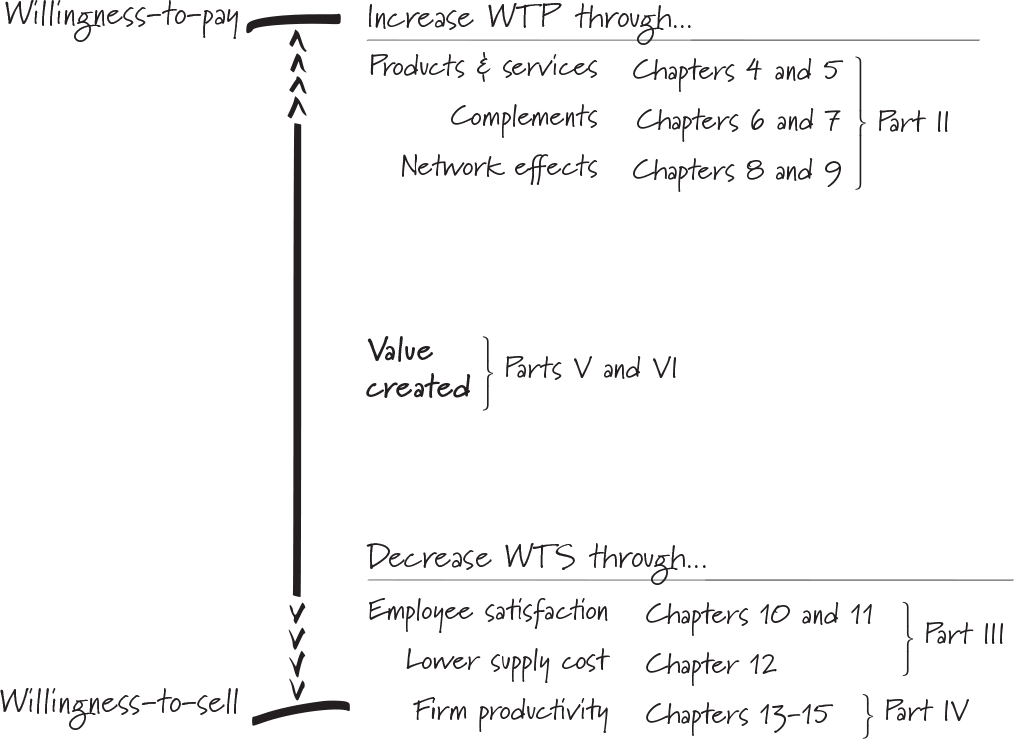

The basic intuition underlying value-based strategy could not be simpler: companies that achieve enduring financial success create substantial value for their customers, their employees, or their suppliers. The idea is best captured in a simple graph, which I call a value stick (figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1 How businesses create value

Willingness-to-pay (WTP) sits at the top end of the value stick. It represents the customer’s point of view. More specifically, it is the most a customer would ever pay for a product or service. If companies find ways to improve their product, WTP will increase.

Willingness-to-sell (WTS), at the bottom end of the value stick, refers to employees and suppliers. For employees, WTS is the minimum compensation they require to accept a job offer. If companies make work more attractive, WTS declines. If a job is particularly dangerous, WTS increases and workers require more compensation.4 In the case of suppliers, WTS is the lowest price at which they are willing to sell products and services. If companies make it easier for their suppliers to produce and ship products, supplier WTS will fall.

The difference between WTP and WTS, the length of the stick, is the value that a firm creates. Research shows that extraordinary financial performance (returns in excess of a firm’s cost of capital) is rooted in greater value creation.5 And there are only two ways to create additional value: increase WTP, or lower WTS.6 Strategy is conceptually simple, and simpler strategic thinking, I am convinced, will lead to better outcomes.

Renew Blue

An example of the power of this approach is Best Buy, America’s biggest consumer electronics and appliances retailer. In late 2012, the company was looking for a new CEO. Imagine yourself taking on this role. It seemed impossible to succeed. Best Buy, most of us thought, was doomed. Amazon had successfully grown its electronics business at the expense of Best Buy, offering consumers a broad selection of products and aggressive pricing. At the same time, Walmart and other big-box retailers stole market share by focusing on the most popular devices and appliances that could be sold at high volumes. Worst, perhaps, was the growing trend among customers to “showroom,” that is, to visit stores to decide which products they liked and then buy them online. Having endured this onslaught, it is no surprise that Best Buy performed poorly. In 2012, the company lost $1.7 billion in a single quarter. Its return on invested capital (ROIC), which had long been in decline but was still in the upper teens, plunged to minus 16.7 percent.7 “It was as if Best Buy was coming to a gunfight with a knife,” said Colin McGranahan, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein. “Best Buy Should Be Dead,” titled Business Insider.

Hubert Joly, a former strategy consultant and most recently CEO of Carlson, a hotel and travel conglomerate, took on the challenge. Recognizing the dire circumstances, Joly and his team devised a plan they dubbed Renew Blue. The core idea was to create more customer value by increasing WTP and improving price perception. Rather than thinking of Best Buy’s more than 1,000 stores as a liability that made it difficult to compete, the company reimagined their role and turned them into assets. Going forward, the stores would serve four functions: points of sale (the traditional role), showrooms for brands that built stores-within-a-store, pickup locations, and mini-warehouses.

Best Buy had allowed Apple to operate its own showrooms in Best Buy stores starting in 2007. Joly expanded the program, adding Samsung Experience Shops and Windows Stores in 2013 and the Sony Experience a year later. Even Amazon eventually opened kiosks in Best Buy stores. The store-within-a-store concept provided the company with a fresh source of revenue and an enhanced shopper experience. Sharon McCollam, then CFO, explained, “When you look at the investments that our vendors have made in our stores, it is incredible. It is literally hundreds of millions of dollars.”8 Vendors also subsidized the salaries of Best Buy employees who worked in their showrooms. Perhaps more importantly, Best Buy was now able to offer deeper sales expertise because the company’s staff, dressed in vendor-branded shirts and supported by consultants, each focused on a specific brand. Not only did the store-within-a-store program benefit Best Buy, the company’s vendors were also better off. By creating a more cost-effective way to reach customers—operating a store-within-a-store is less expensive than running your own store, and vendors can benefit from increased traffic—Best Buy lowered vendors’ operating cost and, as a result, vendors’ WTS.9

Using Best Buy’s stores as mini warehouses proved similarly effective. Joly’s team understood that the speed at which customers received new products was an important driver of their WTP. It is hard to beat instant gratification. Traditionally, the company had shipped from large distribution centers. These were closed on weekends, and the inventory management software was decades old, leading to frequent stockouts and snail-speed shipping.10 Under the Renew Blue plan, products were shipped from the location that provided the quickest delivery— sometimes a distribution center but often a store down the road. By 2013, Best Buy shipped from 400 stores. A year later, that number rose to 1,400, helping the company beat Amazon’s shipping times for the first time.11 Customers also loved the idea of ordering online and picking up the products in Best Buy stores. Within a few years, 40 percent of Best Buy’s online orders were either shipped from or picked up from a store.12

Joly and his team also reassessed the company’s online presence. Like many traditional retailers, Best Buy management had perceived the internet primarily as a threat, a substitute for established ways of doing business. Best Buy had built an online sales channel, but it had done so half-heartedly. BestBuy.com provided sparse product descriptions, few customer reviews, poor search capability, and no integration with the company’s loyalty program. Frustrated customers complained that the site often promoted products that were out of stock. All this changed under Joly. Rather than seeing the internet as a substitute, the company now regarded it as a complement, an investment that would increase the value of Best Buy’s physical stores. Although most customer journeys begin online, many consumers want to touch and feel the products before they make a purchase. Joly banked on converting store visitors into paying customers by matching, for the first time, online and offline prices. Even customers who completed their transactions online added value to the stores; when they picked up their purchases, they often ended up buying additional products and service plans. Recognizing that Best Buy’s online presence was supporting store activity, the company accelerated its investment in BestBuy.com. In just a few years, the site came to rival leading e-commerce sites, and online sales boomed. By 2019, the company derived one-fifth of its revenue from e-commerce.

Renew Blue provided Best Buy a new lease on life. Look at all the ways in which Joly and his team managed to increase customer WTP and decrease vendor and staff WTS (figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2 Value creation under Renew Blue

By 2016, when Joly declared that Renew Blue had achieved it goals, Best Buy’s ROIC had climbed from negative territory to 22.7 percent, and EBT margins had doubled. The company’s share price quadrupled in only six years.*

The Best Buy turnaround illustrates some of the key principles of value-based strategy.

- Companies that excel at creating value focus squarely on WTP and WTS. Every significant initiative is designed to either enhance the customer experience—that is, increase consumers’ WTP—or make it more attractive for vendors and employees to work with the company, in other words, decrease their WTS. Initiatives that fail to meet this test are cut. For example, Best Buy eliminated its Amazon-like marketplace—an exchange that allowed third-party vendors to sell their own products—because it failed to create value.

- Companies that outperform their peers increase WTP or decrease WTS in ways that are difficult to imitate. Best Buy’s most distinctive asset is its large network of stores. Skillful, impartial service provided in a brick-and-mortar environment is difficult for Best Buy’s competitors to match. Amazon lacks a similar physical presence. Walmart is not known for high-touch service. Apple is disinclined to give impartial advice.

- Simplicity opens up room for creativity and broad engagement. Joly describes the Renew Blue strategy in the simplest of terms: “Our mission is to be the destination and authority for technology products and services. We are here to help our customers discover, choose, purchase, finance, activate, enjoy, and eventually replace their technology products. We also help our vendor partners market their products by providing them the best showroom for technology products, both online and in our stores.”13 No PhD required. It is plain to see, all that matters is customer WTP and vendor and employee WTS. Looking at Best Buy’s turnaround, it is astounding how fast the company moved, how quickly it created and implemented dozens of initiatives—many more than I am able to describe here. The simplicity of the strategy is key if one is to execute at breakneck speed. Every executive, every store manager, every employee with an idea about ways to raise WTP or lower WTS can be sure that they are helping move the company in the right direction.

- Many of the most successful companies focus on their competitive position inside an industry, as opposed to the average performance of their segment of the economy. Joly explains, “If you remember, [in the past] the message from this company was all about the headwinds in our industry. [Today,] we never talk about the headwinds.… What we do has more impact, we think, than the overall environment.” There are three reasons why this type of thinking is prevalent in companies that create exceptional value. A first is that in most industries, variation in profitability inside the industry exceeds the profitability differences across industries.14 In other words, your best opportunities are almost always in your current industry, even if it is considered a difficult place for business. A second reason to focus on competitive positions inside an industry (versus industry attractiveness) is that positive industry fundamentals will simply be reflected in the multiples that companies need to pay to enter an attractive industry. Finally, for companies that happen to be in struggling industries, a focus on headwinds is demoralizing, and it likely contributes to decreases in productivity. “It’s a virtuous cycle,” says Joly. “Once you start winning, people get more excited, more confident.” Best Buy’s internal data show that by 2013, staff engagement was higher than at any point since 2006.15

Many questions linger about Best Buy’s future, of course.

- Was Best Buy lucky? No doubt. I don’t know any organization whose stellar performance does not, in part, reflect good fortune. Hugely popular electronics products such as new generations of iPhones and video game consoles surely played a role in Best Buy’s turnaround. So did the lessened competition after Circuit City, RadioShack, H. H. Gregg, and other smaller electronics retailers closed their stores. Sheer luck, however, rarely leads to exceptional long-term value creation. The best firms build on their circumstances, whatever those may be. Value-based strategy is not about the hand that you are dealt. It is about better ways to play.

- Will Best Buy be a long-term success? Time is generally not kind to high-performing organizations. When I examine companies that have created exceptional value, I find that the average firm loses about half of its competitive advantage over a ten-year period. In Best Buy’s markets, Amazon (in consumer electronics) and home improvement companies like Lowe’s (in appliances) continue to grow market share. In 2018, Amazon, for the first time, narrowly beat Best Buy to become the largest US consumer electronics retailer. Relative market share is important in an industry where 80 percent of cost is the cost of goods sold. The larger a company’s market share, the better positioned it is to bargain with its vendors. “To win, we have to lead,” acknowledges Joly.16 While these dynamics are challenging, he is characteristically upbeat: “We get 26 percent of our consumers’ electronic spending. That’s embarrassing. If we get a third, it would still be embarrassing, but the growth for the company would be tremendous.”17 Value-based strategy provides clear guidance on the potential sources of growth and the opportunities that promise to be of greatest value.

A Preview

In the pages that follow, I will take the principal idea that animated Best Buy’s strategy—long-term financial success reflects superior value creation—and explore how firms in different industries and business contexts have applied this approach in practice. Think of this book as a journey along the value stick (figure 1-3).

Figure 1-3 Key value drivers

Part one (“Exceptional Performance”)—We ask why some companies are so much more successful than others. For example, aren’t the home improvement retailers Lowe’s and Home Depot essentially clones? How can it be that one, Home Depot, is far more profitable than the other? The answer, it turns out, has much to do with how companies create value for their customers, their employees, and their suppliers. It is surprising, perhaps, but true nevertheless: the companies that perform best do not think about themselves first and foremost. They dream up ever better ways to create value for others. Think value, not profit, and profit will follow.

Part two (“Value for Customers”)—Do you tend to root for the underdog? If so, you will love the story about the ways Amazon gained a toehold in the market for consumer electronics in fierce competition with then-dominant Sony. Sony had it all: the best e-reader technology, a stellar brand in consumer electronics, and a marketing budget the size of a small country’s GDP. Amazon’s edge? A better way to think about value for customers. Early in my research, I had an intuition that sales-driven organizations (like Sony) and companies that focus on WTP (like Amazon) would show similar performance. But this intuition turned out to be wrong. Companies that train their lens on WTP have a significant long-term competitive advantage.

Some approaches to raising WTP are obvious: increase the quality of your products, enhance their brand image, innovate. But even strategies that are often overlooked can be exceptionally powerful. For instance, it is fascinating to observe how some companies leverage the power of complements: products and services whose presence raises the WTP for other products and services. Think printer and toner, cars and gasoline. Michelin and Alibaba Group rely on complements to supercharge their entry into new industries. Apple uses them defensively to soften the blow from declining prices. Harkins Theatres cleverly offers complements to fill seats in its movie theaters. If you compete on the basis of your products and services alone, if you fail to recognize your complements, there is a good chance your business is already in trouble.

Speaking of trouble, are you surprised that ride-sharing companies such as Uber, Grab, and DiDi have such difficulty attaining profitability? Shocked that investors loved the companies at first, only to sour on them subsequently? The swing in sentiment reflects how we think about network effects. Network effects create a positive feedback loop: more passengers attract more drivers, which, in turn, attracts more passengers. Many of the leading tech companies rely on network effects to drive WTP. At an extreme, network effects can create so much customer value that markets tip; we are left with a single firm. As the ride-sharing market illustrates, however, winner-take-all outcomes are rare. More important than knowing that your company benefits from network effects is your ability to gauge their strength. What are the forces that enhance them? When do they fade?

The companies that we encounter in part two could not be more different from one another. They range from cosmetics to pharmaceuticals, from publicly traded to family owned, from global champions to regional upstarts. And yet they all rely on the same trio of levers to increase WTP and create greater customer value: more attractive products, complements, and network effects.

Part three (“Value for Talent and Suppliers”)—Our attention will swing to the bottom of the value stick. We will meet companies that gain a competitive advantage by decreasing the WTS of their employees and their suppliers. In competition for talent, firms pursue two approaches to gain leverage: offer more generous compensation or make work more attractive. While the two strategies seem similar at first—they both create greater employee engagement and satisfaction—they have vastly different consequences. Increases in pay shift value from the company to its employees; there is no value creation, only redistribution. By contrast, more attractive working conditions create more value. I find it astonishing to see how smart companies find ever new ways to create value for their workforce and how they share that value with their employees. Because leading companies are so adept at reducing WTS, it is not unusual to see that they enjoy labor cost advantages of 20 percent or more. If your organization competes for employees solely by offering more generous compensation, you can of course attract highly capable and engaged individuals. But you will have missed an incredible opportunity—boosting productivity by creating value for your workforce.

Strategies that lower WTS also pay off in improved supplier relationships. Even prior to the Covid-19 pandemic and the increasingly frequent disruptions of global supply chains as a result of climate change, experts readily recognized the value of close and adaptable collaborations with suppliers. If you find ways to reduce a supplier’s cost of working with your company, you can capture a part of the value that you helped create. However, what is straightforward in theory is often difficult in practice. Many buyer-supplier relationships do not live up to their potential, not because it is challenging to see how one might create value but because we fear the other party will capture most of the benefits from a successful collaboration.

It is highly instructive to observe how companies navigate this tension. We will see how Tata Group liberated Bosch to pursue breakthrough innovation, even in a situation with strict cost constraints. We will learn from Nike how to break suppliers’ addiction to volume. Dell will teach us how to leverage supplier capabilities in order to pursue projects for which there is little internal support and funding.

In my conversations with executives, I regularly meet managers who describe their products and services as being commoditized; there is no way to raise customer WTP. (I confess I am usually skeptical. I never quite know if “commoditization” reflects an incontrovertible industry fact or a lack of imagination.) Even if opportunities to raise WTP are truly scarce, however, most companies have rich prospects of attaining stellar performance by creating more value for their employees and their suppliers.

Part four (“Productivity”)—If you had to guess, how wide do you think the productivity gap is between an industry’s bottom 10 percent of companies and the top 10 percent? It is substantial. In the United States, leading companies are twice as productive as the weakest organizations. In emerging markets, top performers best the least efficient by a factor of five. Imagine—a company that produces five times as many products with exactly the same inputs! Whenever firms increase their productivity, cost and WTS fall at one and the same time. In this part of the book, we will explore three mechanisms that raise productivity: economies of scale, learning effects, and the quality of management.

If you wonder why JPMorgan Chase doubled in size after the Great Recession in 2008, when we were questioning if some financial institutions were “too big to fail,” look to economies of scale as one important reason. A classic in the strategist’s playbook, scale economies remain an influential means of lowering cost and WTS. And so is learning—the idea that costs decline with cumulative output. In fact, in the age of machine learning and advanced analytics, learning has become even more important. Anomaly detection algorithms, for instance, can result in substantial cost reductions because faulty parts are sorted out before they enter production workflows. While steeper learning curves promise considerable efficiency gains, the strategic effects of learning can be surprising. Consider the value of being the first to detect a better way of working. When everyone learns at the speed of light, being early means very little. Your competitors will catch up quickly. Paradoxically, the strategic effects of learning are most valuable if learning reduces cost at an intermediate pace—not too fast and not too slowly.

Scale and learning are on the evergreen list of productivity-enhancing strategies. By contrast, research on the importance of basic management tools is fairly recent. When asked how well their company is managed on a scale from 1 to 10, most managers rate their organization about a 7. Surprisingly, these ratings tell us very little about the chances that a company actually implements modern management techniques that help drive productivity. And I am not thinking of next-generation ideas. Across many industries and countries, companies fail to adopt basic tools such as goal setting, performance tracking, and frequent feedback. If you are searching for ways to substantially raise the productivity of your team or your company, chances are these management techniques are among the most promising opportunities to raise your game.

Part five (“Implementation”)—As the first parts of this book show, strategies that lead to exceptional performance are built on three ideas: value for customers (raising WTP), value for employees and suppliers (reducing WTS), and increases in productivity (lowering cost and WTS). Building on this insight, in part five (“Implementation”), we will explore how companies move from conceiving a strategy to putting it into practice. Observing brilliant strategists at work is an incredible experience. I see them making three critical choices.

First, among many options, they invest in a small number of value drivers to pull ahead of the competition. Value drivers are the criteria that make up WTP and WTS. They are the product and service attributes that are important to your customers. For instance, when choosing a hotel, consumers typically consider value drivers such as location, room size, staff, and friendliness, as well as the hotel brand. Accomplished strategists are comfortable promoting only a few value drivers and withholding resources from many others. How did Paul Buchheit, Gmail’s lead developer, express this idea? “If your product is great, it doesn’t need to be good.”18

Second, for each of the critical value drivers, accomplished strategists develop a deep understanding of how they influence WTP or WTS. For example, they know that scale is no panacea. (Comparing size or market share across the firms in the S&P 500, for instance, tells you exactly nothing about their profitability.) But strategists also know that scale can be all-decisive in some situations—for example, in the presence of network effects or scale economies. In each instance, they understand deeply how a value driver increases WTP or lowers WTS.

Third, successful companies often use smart visuals to cascade their strategy throughout the organization. I will discuss one such visual, value maps, to illustrate how ideas about value get connected to specific key performance indicators (KPIs) and projects that increase the performance of the organization.

Part six (“Value”)—Strategy is conceptually simple, because it serves a single purpose: creating value. Companies that do this well end up leading their industries. We will see how Tommy Hilfiger did just that for an often-disadvantaged group of people, persons with disabilities. Imagine what this must be like, showing up at work every day with the single ambition of making life better for a group of customers, the people who work for your organization, the suppliers with whom you collaborate. Value or profit is a false choice. Exceptional financial performance reflects value creation. Let me say it one more time: think value, and profits will follow.

This insight is important for reasons that go beyond the performance of companies. Unless you have been hiding in some faraway castle, you know that business does not enjoy the best of reputations these days. In recent surveys, only about a quarter of participants say they believe that their organization “will always choose to do the right thing over an immediate profit or benefit.”19 Fifty percent of the population now agrees that “capitalism, as it exists today, does more harm than good in the world.”20 Even corporate leaders seem to agree. The Business Roundtable, a club of large US companies, disavowed shareholder capitalism in 2019, arguing that it is the responsibility of corporations to deliver value to all stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers, as well as shareholders. But wait—isn’t this what (successful) businesses have always done? How, if at all, do corporate leaders and companies have to change?

Value-based strategy is uniquely suited to help us see a way forward. To make progress, value must sit at the very core of every business. Even the most vexing problems can bend when we apply enough creativity and imagination to create more value for customers, employees, and suppliers. As far as value creation is concerned, there is no difference between shareholder and stakeholder capitalism. Creating more value—increasing WTP and lowering WTS—is simply good business. But value-based thinking also shows that we have considerable degrees of freedom to decide how to share the value that we create. Companies can balance multiple interests; there is no reason to believe that firms need to be beholden to shareholders alone. As we debate how value is best distributed, value-based thinking can serve as a helpful guide. Building on the ideas in the pages that follow, my hope is that we will bring to these conversations rich imagination and our most noble instincts.