In June 2016, Vahidin Feriz, CEO of Car Trim, a Prevent subsidiary, received an ominous fax message. The news was grim. Volkswagen, one of Car Trim’s principal customers, was informing Feriz that it would cancel a €500 million joint development project, alleging quality defects in Car Trim’s leather seats. Volkswagen, under significant financial pressure as a result of its recent diesel emissions scandal, gave only two days’ notice.1 Car Trim sued. When Volkswagen refused to pay damages, Car Trim and ES Guss, another Prevent company, halted all supplies, forcing Volkswagen to interrupt production at six of its plants and idle nearly 30,000 employees.

Payback came two years later. When Prevent attempted to raise prices, Volkswagen canceled all remaining contracts with the group. Now it was the Prevent companies that had to cut back; one even declared insolvency. In 2020, the courts are still adjudicating the dispute.

The Prevent–Volkswagen battle is an extreme example, but tense relationships between buyers and suppliers are common. Amazon, for example, uses its formidable position in e-commerce to impose costly payment terms on its marketplace vendors. It takes the company 22 days to collect revenue from its customers but a full 80 days to pay its bills. The marketplace vendors effectively play Amazon’s bank, helping fund the company’s growth.2 Brick-and-mortar retail offers similar examples. When retailers introduce private-label products, profits rise significantly. One important benefit: the new products help retailers squeeze the manufacturers of branded goods.3

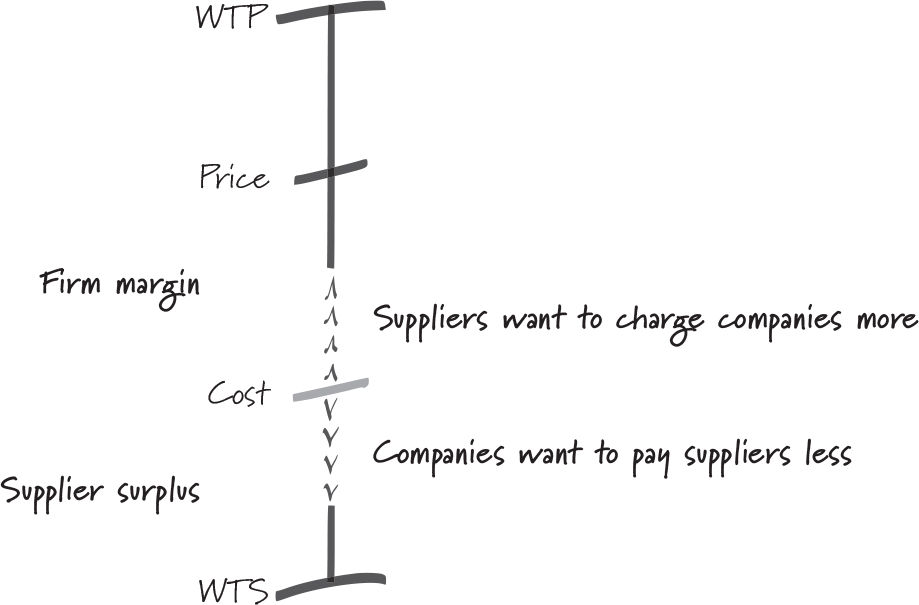

Figure 12-1 illustrates such tensions. Companies hope to increase their margins by paying their suppliers less. Predictably, the suppliers push back. They seek to enlarge their own surplus: the difference between willingness-to-sell (WTS) and cost. These efforts create no value; whatever one party gains, it must come out of the pocket of the other.

Figure 12-1 Companies and their suppliers fighting over fixed value

There is, of course, a second avenue to increased profitability. If you manage to decrease the WTS of your suppliers, more value is created. Your company and your suppliers can be better off at the same time. Your supplier’s WTS, you will recall, is the lowest price that they would ever accept from you. If you pay more than WTS—cost is greater than WTS, as shown in figure 12-1—the supplier will earn a surplus, a margin that is greater than the profitability that is built into WTS.

WTS varies from one buyer-supplier pair to another. It is determined by the relationship between the two. For instance, if a supplier earns bragging rights by providing products to a famous company, her WTS will be lowered. If a buyer is a headache to work with, he will face suppliers with a higher WTS.

Such buyer-specific considerations aside, how do you actually lower the WTS of your suppliers? By making it more cost effective to sell to your organization. Any initiative that makes life easier for your suppliers, any investment on your part that makes them more productive, will lower their WTS and create more value.4 Consider Raksul, a B2B marketplace for printing services. Its original platform allowed customers to compare prices across many of the 25,000 printing companies in Japan. Success came quickly, but Yasukane Matsumoto, Raksul’s founder, was not happy. Every morning, he would look in the mirror and ask, “If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do today?”5 Thinking about Raksul’s listing service, Matsumoto decided the answer was no. He could create far more value. Under his direction, Raksul built a highly efficient matching service, sending client orders to carefully selected suppliers that had idle capacity of the type of printing machine that was required for the job. Printers with spare capacity and the right equipment had particularly low WTS, Matsumoto recognized. Raksul also hired former Toyota engineers to work on improving the printers’ floor-level operations, lowering their WTS even further. The company shared the value it created with the printers as well as Raksul’s customers, who enjoyed lower prices.

Raksul is a good example of two mechanisms that ensure your suppliers benefit from low WTS: careful supplier selection and the transfer of management expertise. In this chapter, we will see how leading firms employ both techniques.

Teaching Your Suppliers

Most companies detail the obligations of their suppliers in comprehensive contracts and service-level agreements. Many also develop codes of conduct that describe their expectations of supplier behavior. Nike, in early 2000, sought an even closer collaboration with its vendors when it decided to teach them lean manufacturing.6 Lean production, also known as the Toyota Production System, was not a new approach, but it had not been adopted by Nike’s suppliers.7 Gerry Rogers, VP of global sourcing and manufacturing, explains, “The ability to find the right capability around the world is actually quite finite, particularly in this industry where you have tremendous product specialization. It’s not in anyone’s interest to engage transactionally and walk away anytime there is a problem. As the companies grow, they come up against new obstacles that we can actually help them with by showing best practice capability building or collaborating together.”8

Lean production required Nike’s nearly 400 shoe and garment suppliers to make profound changes. For example, traditional apparel factories separate sewing, ironing, and packing activities, and they have high inventory buffers between each process. Factories that adopt lean production move machines and workers into one production line, and they balance process cycle time (the time it takes to finish a garment) and takt time (the time between the start of one piece of clothing and the next, which is set to match customer demand). To be certified as lean, Nike asked its suppliers to make eight such changes. They included installing an Andon system, which allows workers to quickly signal production problems and perhaps even stop the line; using in-station quality inspections to prevent defects from being passed on; and showing evidence of 5S, a set of practices that reduces waste and promotes productivity.9

To prepare its suppliers, Nike opened a training center in an active factory in Sri Lanka. Vendors from across Asia participated in an eight-week program during which they studied the theory of lean, observed the method in practice, and worked with a Nike manager on a strategy to roll out the system in their own factories. Seeing early success in productivity and profitability, Nike doubled down on its effort with Lean 2.0, a program that promoted increased automation and worker engagement. Even a small pilot program demonstrated the significant potential of greater mechanization. At one factory, productivity increased 19 percent, quality moved up by 7 percent, and workers said they felt more valued.10 By 2018, 83 percent of Nike’s production came from factories that operated under Lean 2.0.

At around the same time, Nike began to work with Niklas Lollo and Dara O’Rourke, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, to better align worker compensation in vendor factories with lean production methods.11 To set the price for a piece of clothing, Nike negotiates standard allowable minutes (SAM), an engineering-based measure of production time, with its suppliers. The factories then use SAM to determine the pay rates for their workers, who try to beat SAM to make more money. Because SAM is fixed for each garment, workers prefer easy-to-produce styles with which they are familiar. With an unfamiliar design, beating SAM is difficult, so workers focus on overtime pay instead. This approach is at odds with many of the goals of lean production, in that SAM-based compensation provides little incentive to improve quality, reduce inventory, eliminate waste, and build just-in-time capability.

The Berkeley team tested three compensation mechanisms in a Thai factory that was already certified Lean 2.0: a productivity multiplier that rewarded more output; the productivity multiplier plus an added bonus for cost reductions or superb quality; and the multiplier plus a target wage.* Workers who participated in the experiment were guaranteed to earn at least as much as they had prior to the experiment. The researchers also installed LCD panels that displayed wage and productivity information for each production line. (Fewer than 50 percent of global garment workers receive pay slips that show the number of hours they have worked.)12 Figure 12-2 shows how performance changed compared to production lines that did not participate in the compensation study.13

Figure 12-2 Compensation experiments at Nike vendor factories

The study produced rich insights both for the vendor and for Nike. For example, the target wage proved particularly effective in raising pay and profitability, even though no team ever decided to go home after hitting the 650-baht target. In focus groups, workers said it was more important to earn additional income when production ran smoothly. Across all three interventions, workers earned more and vendor profits increased. This is possible because productivity rose by more than 6 percent in each of the production lines, an accomplishment that also reflects the steep decline in worker turnover. Quality—which was high even at the outset—further increased in the bonus and target groups. One of the lines that had received only the multiplier incentive proved an exception. This line became increasingly dysfunctional. Workers criticized each other for a lack of skill, their supervisor for poor communication, and management for an insufficient flow of quality material. A full 70 percent of these workers quit. (Another line with the same incentives did just fine.) The meltdown is a useful reminder of the stress that can result from high-powered incentives. Factory management, however, remained undeterred. When the experiment ended, productivity multipliers were introduced factorywide.

Teaching your suppliers to become more productive is an effective way to lower their WTS and create more value. The Nike factories are typical. As a rule, local vendors make significant strides once they start working with multinational companies. They increase their productivity, hire more workers, and experience greater sales success, even outside their relationship with the global firms.14 The multinationals benefit as well. Nike, for instance, lowers SAM over time to take advantage of the productivity advances of its vendors.15 A focus on WTS creates value for both parties—local companies and multinationals.

The Shadow of Value Capture

Even in buyer-supplier relationships that focus on value creation, the shadow of value capture is ever present. Suppliers are anxious that investments in production capacity will not pay off if buyers, seeing the newly installed capacity, demand prices that make the investment unattractive. Buyers fear that suppliers will exploit a close relationship if they become too dependent on a firm.16 Both sides make costly moves to protect themselves. Buyers resort to sourcing from multiple suppliers when it would in fact be advantageous to work with only one.17 Suppliers refuse to work with buyers they do not trust. For instance, when Xiaomi, now a leading smartphone manufacturer, first started, it approached more than 100 leading component suppliers, 85 of whom refused to do business with the fledgling company.18 Value creation is challenging when everyone is anxious about their ability to capture a part of the value that they help create.

So how do leading companies do it? When I speak with supply chain executives who have successfully lowered their suppliers’ WTS and created long-term value for themselves and for their suppliers, I often hear pieces of advice like this.

- Be selective. Developing and maintaining supplier intimacy is challenging and time-consuming. Limit the number of vendor relationships in which you invest.

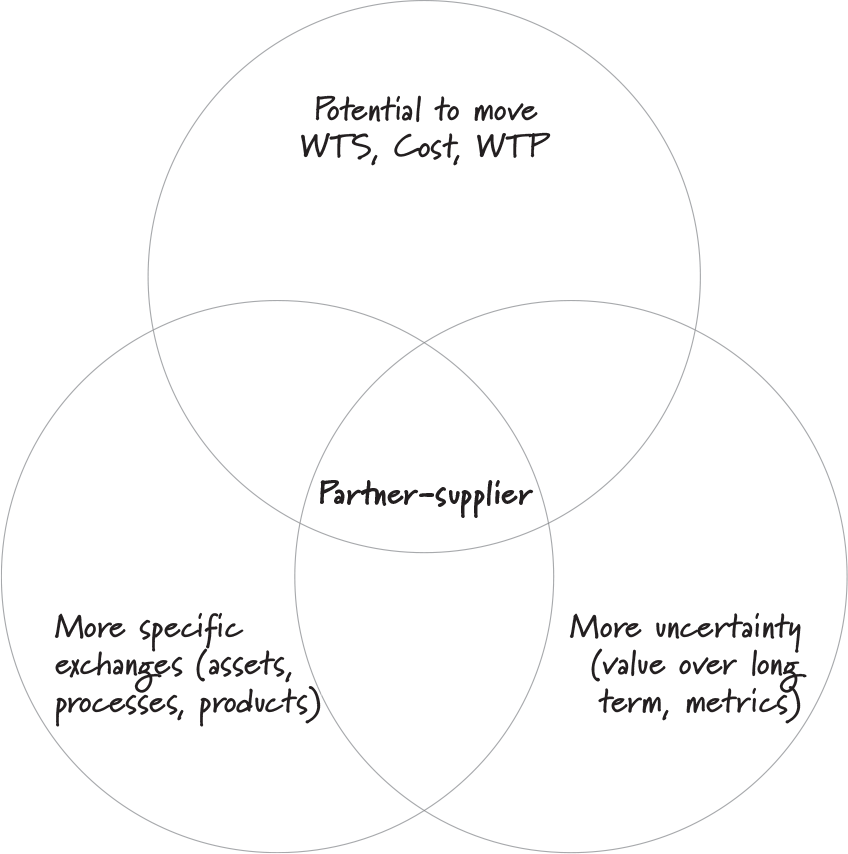

My recommendation is to use three criteria (figure 12-3) to choose the right partners. The first is value potential: close collaborations are particularly valuable if they have the potential to move WTS, cost, and willingness-to-pay (WTP). The supplier of an inexpensive component whose quality barely registers with your customers will not be high on your list of candidates for close partnerships. Second, specificity: Do you ask your supplier to invest in dedicated capacity? Would you like them to develop a novel process that benefits primarily your firm? The more specific the exchange, the more helpful it is to collaborate closely and develop trust. If you fail to do so, the supplier will likely underinvest or not invest at all. Third, completeness: How difficult is it to describe in a contract what you expect of your supplier? Is it possible to list most contingencies? Are you sure you understand how your expectations will evolve over the duration of the contract? Deep relationships are particularly advantageous if contracts are incomplete, if it is hard to describe and measure what you expect of your supplier.

Figure 12-3 Criteria for selecting partner-suppliers

- Get to know your supplier. It is tempting to view your supplier relationships exclusively through the prism of cost, but this lens is too narrow. As a highly successful manager once reminded me, “Supply chains are people, too!”

Many considerations flow into supplier WTS. Just as creating value for clients requires a degree of customer intimacy, being close to your suppliers enables you to see initiatives that would increase supplier surplus. Do you remember Yasukane Matsumoto, the Japanese printing executive? He visits each of his suppliers personally before he decides to build a partnership.

- Focus on outcomes, not billing codes. Significant opportunities to lower WTS often result from changes in your behavior. Many buyers are overly prescriptive in their demands of suppliers, specifying in minute detail what they need to do and how they need to do it. Of course, there are sometimes technical reasons for being precise, but too-detailed specifications often reflect mistrust—will the supplier take advantage if I leave him some wiggle room?—and a desire to create apples-to-apples competition among suppliers. Being overly prescriptive comes at a cost, however. It robs suppliers of chances to adopt novel processes and introduce innovative products and services. It is a tension that sits at the heart of many buyer-supplier relationships. Presumably, we work with suppliers because they possess specialized knowledge and superior skills. Why, then, do we insist on imposing detailed guidelines that constrain them?

When Tata Motors set out to build the world’s least expensive car, the Tata Nano, it asked Bosch Automotive to design the engine. Bernd Bohr, then chairman of Bosch, explains the unusual nature of the collaboration:

Tata did not come to us with large rulebooks or specifications. They simply told us what the weight of the car would be, that it would have a two-cylinder engine, and [that it] would need to achieve Euro 4 emission regulation. In addition, it needs to drive, of course. And that was the difference from other auto projects. Early in the process, one could already see that our teams were coming up with new ideas.… For example, typically each cylinder has an injection valve on an engine; here, our engineers came up with the idea of having one injection valve for two cylinders and give two spray holes so that it takes care of two cylinders.19

Although the Nano ended up not being the financial success that Tata had hoped for, Bosch’s technical breakthroughs found their way into many other engines.20 The key to Bosch’s success was a buyer who was focused on outcomes—in this case, a cost goal—and not on ways to get there.

FedEx Supply Chain had a similar experience working with Dell. When the computer technology company sought to transform its supply chain, it replaced a long list of specific services—hundreds of billing codes—with broad results that mattered the most. In its reverse logistics operation, for instance, Dell went from paying FedEx a fixed fee to dispose of products to asking the company to minimize Dell’s overall loss from returned computers. In close collaboration, the two companies created three channels: one to refurbish machines, one to harvest parts, and a third to discard products.21 John Coleman, general manager at Dell, explains the shift:

[Traditionally,] Dell sold all returned product on a retail basis. If product didn’t meet retail standards, it was scrapped. For years, I had asked Dell to come up with a system to use wholesale as an additional option. It was a good idea, but Dell could not generate internal interest in investing in a project. FedEx Supply Chain had no reason to make investments besides just contributing the idea. [After agreeing on the broad goal of cost minimization], however, FedEx Supply Chain created a wholesale alternative for refurbished merchandise.… [They] made the investments to take the concept from idea to reality.22

With the three channels and the wholesale alternative in place, Dell and FedEx reduced scrap by two-thirds, and they lowered the cost of Dell’s reverse logistics operation by 42 percent in only two years.23

- Align external and internal incentives. With broad goals in place, you can define metrics that align with these goals and link them to financial incentives. FedEx Supply Chain benefits financially, for instance, if the costs of Dell’s reverse logistics operations decline.

In addition to strong external alignment, it is equally important to make sure the buyer’s organization shares the same view of buyer-supplier relationships. Does your purchasing department know that your supply chain manager is developing a collaborative relationship with one of your suppliers? The manager is doomed to fail if purchasing is incentivized exclusively to achieve the lowest cost possible.

- Keep an open mind. The dark side of deep relationships is, well, the depth of these relationships. Once you build trust with a supplier, you have limited incentives to search elsewhere. When Victor Calanog, then a PhD student at Wharton, and I called all 596 plumbers in Philadelphia to offer brochures and a free sample of an innovative floor drain made of elastomeric material, the plumbers who trusted their current suppliers were much less likely to accept the brochure or the free sample. One year after our initial calls, the trusting plumbers had purchased fewer units of the novel drain.24 Even if you have had great success building long-term, trusting relationships with some of your suppliers, reevaluating these relationships might point you to new opportunities to achieve even lower WTS and cost.

Collaboration in supply chains is not a new idea, of course. But the shift in perspective that comes with value-based thinking is useful nevertheless. These are some of the key insights.

- By helping your suppliers lower their cost, by making it easier for them to sell to your organization, you end up helping yourself. Ask not what your supplier can do for you …

- The logic of value capture dominates many buyer-supplier relationships. A reorientation toward value creation makes it easier to share information, align incentives, and discover attractive business opportunities.

- Making value creation the center of a buyer-supplier relationship is hard work, and you want to be careful in the selection of the suppliers with whom you build this type of relationship. In selecting the most promising partners, you need to consider their value potential (how much you can move WTS), the specificity of the investments (how unusual your demands are), and contractual incompleteness (how easy it is to put your expectations in writing).