Chapter 4

Purpose and direction

In this chapter we begin the analysis of the five factors of connected leadership in more detail. The first factor is purpose and direction. When people in an organisation have a common understanding of why they exist as an entity, a clear sense of where they are trying to get to and the strategy to get there, there is a shared mission around which people can unite and flourish.

You will get some practical guidance in establishing a clear purpose and direction as a leader, including involving people through dialogue in the definition of purpose and direction, helping everyone make sense of this through the right organisational cues, storytelling and embedding the purpose and direction into the culture through a variety of techniques. These include cultural symbols, the right processes, sufficient management information, ensuring everyone is clear about their role in interpreting the objectives, ruthless prioritisation and hiring the right people.

A time for renewal

The human resources director at a top law firm in London was faced with a dilemma. The firm could trace its history back for centuries and was a proud member of the prestigious ‘magic circle’ of top law firms. This was a company with a strong ethos and sense of history. Its story was of continuous success and widespread stature in the City and among government departments. What could possibly prevent the firm from attracting the best and the brightest among law school graduates in the war for talent?

But this was precisely the issue the director was confronting. Staff engagement and hence morale were beginning to show signs of deterioration, which was affecting the firm’s ability to appeal to new recruits. The overall problem, and one that went deeper than retention and recruitment, was that the firm seemed to have lost its sense of identity. It was becoming harder for everyone in the firm to identify what they were trying to achieve and why, as the market became more global and brutally competitive.

The firm’s leadership group decided it had to go back to basics and redefine the firm’s purpose and direction for everyone from the senior partners to new graduate recruits and support staff. They recognised that previous success was not enough to attract and retain future talent. They needed to reinvent themselves, to articulate clearly what they were trying to achieve and why it mattered. They needed to create a shared appreciation among the firm’s people and clients of what they existed for, so that they could forge a renewed sense of mission and give deeper meaning to their working lives.

Why direction and purpose?

I use these two words in the same sentence because they are so complementary. They describe where you are going and why it’s important, which is the basis for giving work meaning. They can provide an aspirational definition of something motivating or they can be hollow. The business outcome of having strong purpose and direction is that people in the business are more likely to buy into what they are doing together and why it is important, increasing loyalty, discretionary effort and customer service.

For example, some of the bankers with whom I work see their role in the world in terms of lending or protecting money to enable growth and prosperity, giving families and companies the financial means to fulfil their ambitions. Others, to be honest, see it differently: they see their role and that of the banks for which they work to be simply to make money, to generate maximum profits for shareholders and themselves.

Since the financial crisis of 2008 this dichotomy has been at the heart of the debate, both within and outside banks, on the future of the banking industry. Individual banks have tried to articulate a higher sense of purpose and direction, seeking to engage their colleagues and customers in this ‘mission’, in order to restore trust and long-term independence. Cynics may cite continued misdemeanours as evidence that this is simply window dressing, orchestrated by marketing people to hide the ‘reality’ that the bankers haven’t changed.

I do believe, however, that for some banks and for some leaders this is a genuine attempt to reset the purpose and direction of their institutions and to return to the pioneering work of their founders, who believed in a cause. The jury is still out and it will take time to see who is right. Either way, it demonstrates how important the credibility and aspirational value of an organisation’s purpose and direction really are.

Developing a clear sense of purpose

The need to be clear and explicit about why your business exists, what it contributes to the world and why this is important are all integral to the connected business. The leader’s role is to help to articulate this cause or raison d’être, involving everyone in the definition and maintenance of the purpose and acting as a role model to embed it in the culture.

There are any number of reasons why leaders might need to revisit their purpose – for example, the need to find a new direction after a merger or acquisition, making the purpose more explicit in the face of market disruption, or responding to technological upheavals that challenge the fundamental business model of the organisation. An interesting example of the latter is Shop Direct, which is one of the UK’s largest online retailers. Shop Direct was a large catalogue business, selling to a primarily CDE audience with credit available to spread the payments. With the rise of online retailing the catalogue route to market was in decline, so the company had to reinvent itself fairly quickly.

The turning point in its transformation from ‘paper to pixels’ came when its management redefined its purpose ‘to make good things easily accessible to more people’, which gave everyone in the business a renewed sense of meaning and motivation to make the changes to systems, methods and mindset work in practice. The company turned its finance-driven business model on its head and articulated it as helping people with limited cash to buy its branded jeans and pay over a period of time, ‘making good things affordable to more people’. It became something to be proud of rather than just selling products on credit.

Creating a sense of purpose and meaning attracts talent to an organisation and encourages existing colleagues to give of their best on a day-to-day basis. It provides a reason to come to work, a cause of which they can be proud, and I would argue that it is one of the few sources of sustainable competitive advantage in an era of commoditisation.

Simon Sinek’s golden circle

Why is Apple so innovative year after year after year? After all, it is ‘just’ a computer company with access to the same talent, media, agencies and consultants as everyone else. Or how did Martin Luther King become the catalyst of the civil rights movement in the US? According to leadership writer Simon Sinek, his analysis has found that great and inspiring leaders behave in what he calls a golden circle of ‘why?’, ‘how?’ and ‘what?’.

In a TED talk in 2013 he elaborated on his idea, arguing that this explains why some organisations and some leaders are able to inspire whereas others aren’t.1 As he said: ‘Every single person, every single organisation on the planet knows what they do, 100 percent. Some know how they do it, whether you call it your differentiated value proposition or your proprietary process or your USP. But very, very few people or organisations know why they do what they do. And by “why” I don’t mean “to make a profit.” That’s a result. It’s always a result. By “why” I mean: What’s your purpose? What’s your cause? What’s your belief? Why does your organisation exist? Why do you get out of bed in the morning? And why should anyone care?’

Establishing the right direction

Just as your purpose gives meaning to work, your direction gives clarity. By direction I mean the vision you are seeking to achieve and the strategy to get there. It is your direction of travel, leading towards your core goals as an organisation. It may develop over time, as circumstances change around you, and as technology creates new markets and ways of working. But it needs to have a long-term perspective, looking beyond the horizon, which means that as leaders we need to be bold and imaginative.

When Bill Gates of Microsoft declared, in 1980, the company’s vision was ‘a computer on every desk and in every home’, for many it seemed like an unrealistic ambition. But now it looks obvious as we have witnessed the proliferation of computers, tablets and smartphones in both the business and domestic markets. Microsoft was bold and visionary, and this drove its people to rethink their way of doing business, which until then had been based on a business-to-business software model. Gates was giving his company, and the world as a whole, a vision of the future that would change our lives in so many ways. Microsoft has since then enjoyed sustained success in both software and hardware markets.

Having a clear direction as a business enables you to empower others to make things happen in line with that direction. Along with your purpose and values it creates a clear framework, which provides people with the information they need to interpret their circumstances and make appropriate decisions in the best interests of the business. As leaders we need to ensure our colleagues have that clarity and that it is given sufficient priority.

When the board of the large UK consumer finance company Provident Personal Credit identified that its traditional paper-based operating model was obsolete, and that to maintain its leadership in its sector it needed to reinvent itself as a digital provider of affordable credit, they redefined the company’s strategy and engaged the whole business on a journey of transformation.2 Working with colleagues from across the business, they confirmed their purpose as ‘we lend a helping hand where some other lenders won’t’, articulated a plan to move to a purely digital way of working, and launched two online businesses in product areas where customers were under-served.

In 18 months the business moved from being a highly traditional, paper-based home credit business to being a multi-channel, digitally operated credit provider serving more customer needs. In this case there was a need for a new direction, coinciding, as it sometimes does, with the arrival of a new CEO and a refreshed board. The company kept the story simple, relevant and practical as well as rooted in the proud heritage of being established in 1880 by Joshua Waddilove, who set the trust-based tone when he wrote: ‘The overwhelming majority of the people of this country are honest and will honour their obligations.’ People across the business ‘got it’ and embraced new app-based systems and more customer-centric working patterns with great enthusiasm. The results were dramatic, turning around what had been a steady decline into a business with resurgent profits, improved customer satisfaction and higher colleague engagement.

The leader’s role

These constructs, purpose and direction are relevant at both the team and the business level. So whether you are leading a team, a business unit, a function or the whole organisation, there is value in ensuring that you and your colleagues are crystal clear about your purpose and direction, and committed to their achievement. Where do you begin with the task of defining or refining your team’s or organisation’s purpose and direction? It helps to break it down into a series of actions, which I have listed below, along with your role as the leader in doing it well.

‘Developing a clear and simple plan based on what our customers want has been of critical importance in turning around our performance as a business. Getting the wider team involved in defining a clear direction and plan to achieve it, in line with our values, and then executing it with passion and discipline, has helped us generate excellent business results.’

Roger Whiteside, CEO, Greggs plc

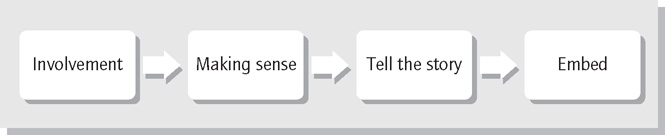

In making purpose and direction a competitive strength, I start with involvement, because the work of refreshing or defining your purpose and direction is best done not in isolation but rather as an integrating activity. Next comes helping people across your organisation to make sense of it so they can internalise it and build it into their mental model of what work means. To succeed here is important to tell the story well, which I explore in a practical way. And finally I look at how you can embed it effectively. This is summarised in Figure 4.1.

figure 4.1 Making purpose and direction a competitive strength

Each organisation is different, and it may be that you feel this is all well covered in your business. I hope that at the very least this is a useful checklist to work through and to use to reflect on how you might tighten up across your organisation the depth and breadth of commitment to your purpose and direction.

1 Involvement

The first, most important, step is about involvement: involving people through dialogue in the definition of what the purpose and direction are, in whatever format the organisation chooses to articulate it. This is about having a rich and in-depth dialogue, involving many people, connecting, not simply pronouncing from on high.

In practice this often means setting up a consultation exercise across the business, either online or through face-to-face discussion groups. It is helpful to get input from customers and other key stakeholders such as unions or investors. It is important that it is a genuine consultation. If you don’t intend to take on board what you hear and amend your purpose and direction statements as a result, it is better not to start, as it is likely to lead to increased cynicism about the outcomes.

As the leader you and your team have an editorial role that is best exercised with care and a light touch, to balance involvement with getting great outcomes that are inspiring, relevant and distinguishing. Too much ‘design by committee’ and you will typically end up with a bland and less useful document. Too little input from everyone and it risks looking like a fait accompli. It is also helpful to adopt distinctive language and design the outcomes in a highly accessible and eye-catching way, so that they stand out as items of intrinsic worth. I have seen people treat the best physical examples such as books and graphics as collectors’ items, worth keeping for posterity. But form can only be as good as function and the content deserves your attention first and foremost.

How you communicate your purpose will depend on your business and its culture, but it is in my view best to be brief. IKEA exists ‘to create a better everyday life for the many people’. The interesting phrase ‘for the many people’ suggests affordability, democracy and equality, which are appealing characteristics for the company that has furnished so many new homes around the world. The IKEA statement also creates an emotional connection which helps it resonate with colleagues and customers alike.

Defining purpose needs to be simple, emotional and compelling. Defining direction needs to be similar but more detailed. Helpful strategic plans typically incorporate a powerful statement of vision and long-term goals as well as a set of key activities to get there. One without the other is like trying to use satnav without a postal or zip code. Again, to do this in a connected way requires you to consult, listen and synthesise the ideas and insights of many people from inside and outside your company. By involving people in the process you plant the seeds of commitment to the outcome.

In one company with which I work the CEO spent 12 months engaging with leaders and colleagues from across the business to redefine direction and purpose. Through a series of workshops, discussions and roadshow events he enabled the organisation to be clear about why it exists (purpose), what it is trying to achieve (vision) and how it behaves (values, which we will discuss in the next chapter).

The CEO started by telling stories of how other businesses had approached some of the challenges this business faced. He explored with his immediate team where they wanted to go and why it was important. He then developed colleagues in the wider leadership group to enable them to share stories and have discussions with their teams, spreading ideas about the purpose and vision and engaging people in dialogue about what they meant. He was in effect helping people to get their heads around the way forward, what Weick would call ‘sensemaking’ across the organisation, which ‘involves turning circumstances into a situation that is comprehended explicitly in words and that serves as a springboard into action’.3

By working with people across the business to define the intended destination as well as the coherent set of activities that will enable you to get there, you are creating a shared sense of mission clarity, which enables everyone in the business to make decisions ‘on the ground’ that are consistent with that mission. When we combine this with clarity on why it is all important in the first place, we have a helpful framework for empowering people across the business in a coherent way so that they are aware and equipped to make their contribution to your overall success as an organisation.

2 Making sense

We are all making sense of what’s going on around us all of the time. We are picking up cues from what we see, hear or feel and interpreting them in the context of our assumptions and experience. If I arrive on my first day at a new job, for example, and see that the parking spaces at the front of the building are reserved for senior managers, I am likely to make sense of that piece of data as follows: the bosses here see themselves as more important than the rest of us and they value their time more than mine; this is likely to be a hierarchical place to work, where I will probably be valued more for conformity and delivering my given objectives than for challenge and innovation; therefore I will need to manage my behaviour to demonstrate respect for more senior people and not rock the boat by asking too many questions. I enter the building with my shoulders slightly lower. It is, perhaps, an obvious example, but I would suggest that we are all making these often subconscious judgements all day every day.

As leaders we need to be conscious of and manage these signals so that they create a coherent set of information that rings true for people, rather than creating dissonance from inconsistent signals and actions. The CEO of the parking space company above may have thought that it was more efficient for him and his team to be able to park close to the entrance to get maximum value for the company from their well-paid time. He may not have considered how others would see it as a statement of relative importance. Or he might have thought that this symbol sent exactly the right message to all colleagues: that he was the boss and that he wanted everyone to focus entirely on executing his strategy effectively. Whatever the intention, the consequence was to make me feel less empowered, less willing to take risks and, frankly, less important than the boss and his team. Whatever inspiring words I heard in my induction about the type of company I had joined, I was likely to balance that against the evidence of the unequal parking arrangements I had witnessed on arrival.

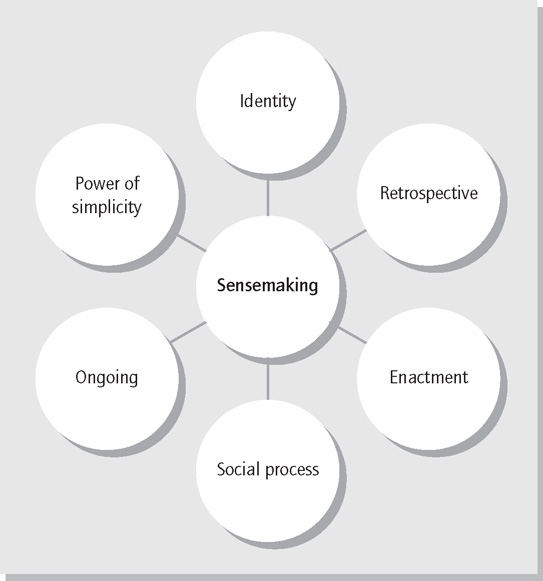

As leaders we can use our human desire to make sense as a helpful way to increase employee engagement and discretionary effort. Weick describes ‘sensemaking’ as how people make sense of the organisation in which they work as a social process of storytelling, discussion and making sense of complexity together, which is a helpful way to view the social processes involved in the transition to more connected leadership.4

So what can we learn from the research into sensemaking in organisations to help us engage our people with our purpose and direction? I have taken some of Weick’s key insights and summarised what they tell us about how to engage others and what we as leaders can do to make it work faster and more effectively – see Figure 4.2.

figure 4.2 Sensemaking

Identity

First, sensemaking is grounded in identity construction: that is, for each of us, how we define ourselves as a person. So at work, we are all thinking about how we align with this organisation: how does it give me meaning and build my self-worth? As leaders we can help people to work this through positively by appealing to both their personal and collective identities. So this means making each person feel valued in their own right as well as enabling them to identify with the organisation’s purpose and direction, so that they see it as part of their own value as a person. In other words, you want to help create a compelling shared identity for your people.

In one retailer we created a workshop that line managers ran with their teams in which everyone was encouraged to articulate the part they played in the wider purpose of the business and what it meant to them personally, so that they made explicit the linkage between personal and business identity. This led to a key shift in perception for many as they articulated how they valued their role in achieving their shared purpose more highly as a result.

Retrospective

Second, sensemaking is, at least in part, grounded in what has already happened. People pay attention to things in the past to help make sense of the present, so as leaders it is helpful to recognise the importance of feeling that the past is important. You can do this by demonstrating your respect for the history of your organisation and by identifying how it helps to tell your collective story of your value and role in the world. You may need to over-simplify history to help the process, but as long as you are telling a ‘plausible history’ it is okay if it helps your people feel comfortable with the present. In one large bank, for example, we drew on the proud history of the founding fathers (and how they had taken personal risks in times of war to protect their customers’ money and records) in order to reconnect leaders with their underlying sense of purpose beyond making money.

One way to put the future in context is to create a strategy map, a physical or virtual map showing where you have been, where you are now and where you are going. Such visual tools are then useful as a basis for workshops and team meetings at which people can discuss (and make sense of) the visuals and through this process place the future purpose and direction as a natural extension of the past. At the large bank mentioned above, we used a strategy map that included the personal stories of courage and customer loyalty from the founders. These were threads that connected the past to the intended future of the bank as a trusted institution serving its customers with bravery and integrity.

Enactment

The third insight about sensemaking is that what we do at least in part creates our future, as we take action to test our assumptions and explore what is happening around us to understand it better (what Weick calls ‘enactment’). As leaders it is therefore helpful if we can create rituals, routines and ways of doing things that ‘institutionalise’ constructs such as our purpose, direction and values, so they become part of our shared ‘reality’. As we get people to do things to create a new ‘reality’ we are helping them to internalise it and integrate it with their view of the world.

In one fast-moving consumer goods business, where the brands had traditionally operated as separate business units, in order to signal a shift to being more collaborative the leaders changed the chairman’s annual recognition awards from focusing on the brand of the year to recognising the innovation of the year. The award started going to cross-brand initiatives such as shared technological innovation or shared market research, thereby celebrating cross-brand innovation in order to emphasise the importance of collaboration.

Social process

The fourth insight from Weick is that sensemaking is a shared and social process. Human thinking and social functioning are intertwined, in that we make sense through interaction with others, reflection and seeing how ‘things fit’. As leaders we know that dialogue is key to engaging with others, and in developing a shared sense of direction and purpose. We should also pay attention to the labels we attach to things as they convey symbolic shared meaning.

We can, for example, use different words for the same event: a forum, a committee meeting, a briefing or a workshop. Each conveys a different meaning to those who attend (and those who don’t), suggesting in the examples above a dialogue, a formal exchange, a monologue or a shared activity. People will turn up to the event with different expectations, which will influence how they then participate. Essentially, we need to pay attention to what we say and how we say it. If we can create a simple set of terms and language that everyone understands, we will have helped our people to think in a more collective and coherent way.

The importance of dialogue was demonstrated at one financial institution, established in the 18th century, where as part of a transformation programme every manager was asked to have a weekly ‘huddle’ to create more teamwork and flexibility in ways of working. For some managers this was really uncomfortable, especially those who had worked at the company for many years and were used to a more traditional, hierarchical approach to management. But gradually the huddles became an established ritual and started to have an effect, causing more dialogue, leading to more sharing of information between team members to help each other be effective, and helping to loosen up the culture and increase collaboration across the teams.

Ongoing

The fifth insight from sensemaking that is useful to us as leaders is that it is an ongoing process. People are always in the middle of things, ‘in flow’ as Weick calls it, and interruptions to this flow can cause an emotional response from people. We can use specific events therefore to draw people’s attention at particular times, to punctuate the flow so we can focus on specific points, such as our purpose, and to help people to crystallise meaning together. Town hall meetings have been used for many years for this reason, drawing everyone together to make announcements and focus on particular topics such as strategy and performance. But we also need to take care that our ongoing routines are aligned to our shared purpose and direction, as it easy for them to become redundant rituals that at worst perpetuate old thinking.

Power of simplicity

The final insight from sensemaking is how powerful simplicity can be. People need plausibility rather than accuracy in order to believe in a cause. In our everyday lives we need to filter noise to see clear, understandable signals. So as leaders it is helpful to recognise that simplification enables action. Above all, a strong, simple story energises action. If we can provide plausible reasoning to fit the facts, we can energise others to act with greater understanding and commitment, and this is typically more important than logical certainty. A story that puts the facts as we know them into perspective with a plausible level of certainty is more likely to inspire people than a detailed business case. I will look at how to create a great story next. Lego’s purpose is to ‘inspire and develop the builders of tomorrow’, which encapsulates its role in both play and education and is part of why the Danish company has enjoyed such success from simple plastic blocks.

3 Tell the story

What we have been looking at in this chapter is often described as being part of the organisational narrative, i.e. the story that helps us make sense of what’s really important about this business. I remember a senior executive at one client company who was always able to communicate with people at all levels of the organisation and with its customers with ease. I realised that what he was doing in each case was telling a simple story, adapted for the people involved, which illustrated two or three key points in a natural flow that made whatever he was describing seem much simpler and easier to understand than before. He always started with why something was interesting or significant. Each story had a spine that gave it structure, and it placed the current situation in its context by using relevant examples so we could relate to and therefore see how the future made sense.

For some people like the executive above, this comes naturally. But for the rest of us, how can we learn to tell great stories simply and regularly? I like the technique created by playwright Kenn Adams and popularised in 2012 when Pixar story artist Emma Coats tweeted 22 storytelling tips using the hashtag #storybasics. The list circulated on the internet for months, gaining the popular title ‘Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling’.5 Rule number four on the list is known as ‘the Story Spine’, shown in Figure 4.3.

figure 4.3 The Story Spine

The Story Spine is useful to help us tell well-structured stories. Stories are a powerful way for others to appreciate and learn from an experience without having personally been there. They help us to attach sense and meaning to the information that we receive, to make connections with our past experiences and to retain learning for future experiences.

Adams was looking for a way to distil the structure of a well-made story so that people could understand it. When you are creating a story to help explain a concept or idea, or recount an experience, you can use the Story Spine to ensure it has a memorable structure. It provides a model for a well-constructed narrative, with a beginning that establishes a routine, an event that breaks the routine, a middle that shows the consequences of having broken the routine, a climax that sets in motion the resolution to the story, and the resolution itself.

Try it. It works. Here is a simple example, entitled ‘John’s wife’.

A few years ago I had a boss called John who worked incredibly hard. Every day John was on his email from six in the morning until ten at night, and he liked to be in the office before everyone else and to be the one to turn out the lights on his way home. He set really high standards for himself, and all of us in his team felt under great pressure to live up to those standards.

Until one day, when John’s wife, Mary, was involved in a car accident and was rushed into hospital. She was in intensive care for three weeks and then at home for six months unable to drive or look after their kids. Their two children were both at primary school and needed dropping off and picking up each day. John and Mary did not live close to their parents. Because of all this, John was forced to juggle his time between work and looking after his wife and kids. After a while this caused John’s work to get behind schedule and the quality suffered.

We tried to help, but he insisted on trying to carry on. He finally missed a key deadline for a report he was due to present to the CEO. He thought he was going to get fired, but instead the CEO, to her credit, took him out for lunch and asked him to take a sabbatical until his wife recovered. Relieved but a little embarrassed, John took the time off. He devoted himself to his family, but he also had time to reflect on his priorities.

When he came back to work the CEO asked him how he wanted to work going forward. Ever since that day John has dropped his kids at school every morning, and he works with the rest of us in a more understanding and collaborative way. We still get the work done, but we do it together.

The storytelling executive I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter was also good at making his stories stick. He did this through repetition, ‘playing the broken record’ by telling and retelling his stories until we all had taken them to heart. He would often vary the example or change the emphasis a little, but the underlying narrative was consistent. He knew his persistence paid dividends when he heard other people telling the same stories or using the same phrases. His stories became part of the language of the company and spawned new versions from other people in their own words, as the ripples of engagement were felt across the business. The stories were helping others to make sense of the purpose and direction, to believe it and to make it their own.

Other tips from Pixar’s 22 rules

- Come up with your ending before you figure out your middle. Endings are hard – get yours working up front.

- What’s the essence of your story or the most economical telling of it? If you know that, you can build it out from there.

- What is your character good at, comfortable with? Throw the polar opposite at them. Challenge them. How do they deal with it?

- When you’re stuck, make a list of what wouldn’t happen next. Lots of times the material to get you unstuck will show up.

- Pull apart the stories you like. What you like in them is a part of you; you’ve got to recognise it before you can use it.

- Putting it on paper lets you start fixing it. If it stays in your head, a perfect idea, you’ll never share it with anyone.

- If you were your character, in this situation, how would you feel? Honesty lends credibility to unbelievable situations.

- What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against them.

- Coincidences to get characters into trouble are great; coincidences to get them out of it are cheating.

4 Embed

Finally, it is important to embed the purpose and direction in how the people in the organisation think and act if the result is to be a coherent organism capable of self-regulation. Moving away from the old command-and-control paradigm to a more connected approach implies creating the organisational capacity to maintain travel towards long-term goals without constant control and intervention from senior managers. There are many ways this can be achieved and I will discuss those that in my experience are most helpful in embedding a shared sense of purpose and direction, or ‘true north’, across the whole enterprise.

Cultural symbols

In each organisation there are what Schein refers to as artefacts or symbols of the underlying culture.6 These include physical items such as the working environment, branding and other creative expressions of the organisation, dress codes, induction rituals, how the telephone is answered, the intranet, office layouts and so on. If these symbols are consistent with your purpose and direction, they are reinforcing the messages and are helpful. If, for example, your purpose relates to helping the world communicate and there are symbols that enable open dialogue, such as easy access to senior executives, informal social space, open chat rooms and online team collaboration support, these are reinforcing your purpose. If, however, the symbols are opposite, then the purpose statement in the annual report will sound hollow and disingenuous to colleagues. These artefacts show what is really important.

So it is worth walking around your organisation with a fresh pair of eyes. Ask a new joiner to come with you. Or take a friend or partner into work and ask them what they see and what it says to them. With one retail client we asked managers from neighbouring stores to visit competitors’ and each other’s stores and to observe them as if for the first time. We then asked the managers to report back on what they had seen in the various stores, what it suggested to them about what was important to each company, and to do so for their colleague’s store as well. Neighbouring managers gave feedback to and coached each other based on this experience. This led the managers to develop a deeper appreciation of the importance of symbols and what they say – to colleagues and to customers – and how to manage them more consciously to communicate a more congruent set of messages about what their company really cared about.

Processes

Ways of working and the processes and systems that grow up over time to support them can help to structure work to be efficient and effective. They can also become out of date, bureaucratic or incompatible with the strategic priorities that are important going forward. In one international bank, a year or two after the global financial crisis in 2008, I saw tens of thousands of rules and regulations that had developed over time to reduce risk and manage compliance. The myriad rules had become a barrier to customer service and innovation.

As the bank reacted to the global crisis and the associated collapse in customer trust, it gradually recognised that the rulebook had become an excuse for managers acting with limited concern for customers and even less concern for improvement and innovation. The phrase ‘step in front of the rules’ became a rallying cry from leaders as they sought to inculcate a more customer-centric and values-based approach to work. The number of rules was dramatically reduced and managers were asked to think and behave more as ‘customer champions’. But progress was slow, as the underlying conservatism of the institution held back initiative and risk.

Management information

What information an organisation produces for management purposes says a great deal about its priorities, as well as its regulatory requirements. What senior leaders pay attention to sends a clear signal to other people in the organisation about what is really valued. So it is important to ensure that the management information you request is consistent with your purpose and direction. If, for example, the key performance indicators that the board measures are mainly financial, then any declaration of a wider social or organisational purpose will seem to people to be pretty meaningless. I would recommend therefore that you have a balanced set of measures of performance and that these measures reflect the priorities in your purpose, vision and business strategy. The balanced scorecard advocated by Kaplan and Norton is a helpful way to put together a balanced dashboard of metrics, based on the priorities implied by your purpose and direction.7 Making these measures visible is then helpful in demonstrating that the words and the metrics are aligned.

Know your part

In order to translate a great strategy into success on the ground it is clearly important to ensure that everyone knows their part in making it happen in practice. The most obvious way to help make this true in practice is through ensuring that every person has a ‘line of sight’ between their objectives and those of their team and the wider organisation. I have seen both effective and less effective examples of this in organisations. The difference is often down to the simplicity of the communications that enable local objective-setting conversations to genuinely reflect the wider organisational objectives.

One great example was at Shop Direct, the UK online retailer, where there was a section of the intranet called ‘Know your part’, which visually demonstrated how the company’s purpose and strategic objectives translated into functions and from functions to teams. This level of transparency and clarity enabled people across the business to work it out for themselves and therefore to have a more intelligent conversation with their line manager about what objectives to focus on, and why. This linkage, and the ability to update it when strategic objectives were updated, was one driver in the rapid shift from traditional working practices, such as the annual-range planning cycle, to more short-term, digital and fashion-driven buying and retailing in line with its competitors.

Ruthless prioritisation

In many of the larger organisations I visit there is an underlying frustration with the pace of change and, related to this, the number of projects that are concurrent in the system. In those organisations that have been able to accelerate change I see a ruthless degree of prioritisation, where senior leaders focus on the key projects that will best deliver the changes they seek, and a refusal to countenance adopting more until these projects have been implemented (or moved to the next stage of implementation) successfully. Many organisations have statements of intent about simplification, but in my view only a few make the difficult decisions to allow simplification to happen. Those that do focus on what will make most difference to their customers, what will create a differentiated experience, what will provide unique value to customers now and in the future.

This characteristic of ruthless prioritisation also supports increased agility, so I will return to it in Chapter 9. In terms of purpose and direction, I would suggest that the same level of ruthlessness is required if an organisation is to focus on those projects and activities that most directly deliver the stated priorities. When Dave Lewis took over at the troubled UK retailer Tesco in 2014 he took some bold decisions to refocus the business on its core customer purpose and direction, selling off ancillary businesses such as the blinkbox video service, closing unsuccessful stores and reducing head-office headcount in order to fund the customer value proposition. In a few months he had started to restore shareholder confidence. At the time of writing, there is a long way to go, but it is a good example of ruthless decision making when the company needed to reprioritise and refocus on its core business.

The right people

If you are serious about your purpose and direction you will hire and promote only people who share that sense of what you do and why it’s important. Jim Collins wrote of ‘getting the right people on the bus’ on the journey ‘from good to great’ back in 2001,8 and it is as valid now as it was then if you are determined to build a sustainable great business. This relates also to values discussed in the next chapter: if you encourage and reward people who do not live your organisation’s values, you undermine the values and through your actions tell people that results are more important than how they were achieved.

Getting the right people on the bus works at different levels. At very senior levels your visibility means that what you do and how you behave signals what’s really important around here. At transitions to middle and senior roles the decisions you make on who to hire or promote indicate to others what you want in the future as well as now. These are the decisions that suggest long-term intentions as the organisation selects the leaders of tomorrow. At more junior levels you are signalling what skills and behaviours you want to promote as a business. At Inditex, the successful Spanish retailer, they recruit team players because they believe in the importance of collaboration to make their highly integrated business model work efficiently. So making sure all these recruitment, selection and promotion decisions are in line with your purpose and direction is a clear way to make them a shared priority.

case study

Connected leadership at Standard Chartered

Standard Chartered is one of the world’s leading banking groups with a 150-year history in some of the world’s most dynamic markets. It banks the people and companies driving investment, trade and the creation of wealth across Asia, Africa and the Middle East, where around 90 per cent of its income and profits are made. Its brand promise, ‘Here for good’, underpins its business.

Diversity is important to Standard Chartered. It employs more than 90,000 people, with nearly half being women, and has 133 nationalities and 170 spoken languages represented worldwide. As well as contributing to a rich and varied company culture, this diversity brings a strong competitive advantage, enabling better customer understanding in its diverse markets.

From 2002, Standard Chartered grew its business from about $1 billion of pre-tax underlying profits with about 27,000 people, to a $5.3 billion franchise. Its footprint in developing countries and low exposure to Europe and the US meant that the bank was less affected by the global economic crisis than many of its competitors. ‘It did have an impact, of course,’ says Anton Zelcer, Standard Chartered’s global head of executive and management development. ‘We’ve moved from easy growth to smarter growth.’

The importance of purpose

‘I think if you get your core purpose right then the results will follow,’ says Anton. ‘At Standard Chartered we are clear about our strategy, performance objectives and growth targets. We know exactly where we need to be and what we need to do to get there. We know what’s going to drive the share price. But what sits behind all of that and what will help us to execute on all of the things is our purpose and our culture. And what drives our culture is our leadership.’

Increased regulation in the banking industry has presented a challenge to leaders who now need to focus more and more time on issues of risk and compliance. ‘In many ways, this means it is more important than ever to focus on purpose and what we stand for,’ says Anton. ‘Inherently this is a good place. The culture is really strong. It is a bank filled with good people who want to do the right thing, who truly believe in the brand promise of “Here for good”.’

Purpose and direction

‘A lot of what makes us unique is our rich 150-year history, our international footprint and our culture,’ says Anton. ‘Our purpose is fundamental. It goes beyond a commercial purpose and it’s something people can identify with and connect to. It helps to inform our decisions. It informs our recruitment. We invite people to come in and be a part of that future, to be “here for good” as an individual. To have individuals working with purpose and direction in the context of an organisation that also has a clear purpose and direction is really powerful.’

Shared decision making and collaboration

At Standard Chartered, people across the organisation are empowered to be part of the decision-making process and encouraged to be accountable for creating better outcomes. ‘When it comes to devolved decision making, we have almost 90,000 employees. We have to devolve decision making,’ says Anton. ‘If you don’t share decision-making responsibility, you eliminate trust and you eliminate empowerment. A mistrusting, disempowered organisation operating under very strict and defined boundaries is never going to flourish. Devolved decision making and collaboration are very closely linked. And without both of these things, how can we possibly be agile? If the accountability for decision making is only held by very senior leaders then the impact takes longer to achieve.’

Standard Chartered does of course recognise the importance of a clear decision-making framework. ‘We have corporate decision-making processes in place with governance structures and committees and various guidelines. In our industry, we’ll be judged in the future on the decisions we make today. And often the standards we are judged by change. So it’s really important to make values-based decisions, to know that you’re making a decision based on doing the right thing and not just the right set of standards. It all comes back to culture.’

Collaboration

Collaboration is a key organisational capability at Standard Chartered. Leaders are expected to collaborate and to encourage collaboration in others. Standard Chartered also has a popular internal social media platform which encourages virtual collaboration across the globe. ‘Tools like this are important,’ says Anton. ‘But ultimately successful collaboration also comes down to culture.’

Anton also recognises the wider challenges to collaboration in the financial sector: ‘As long as the banking industry continues to reward individual outcomes then we’re not incentivising collaboration as we need to. The industry needs to think more about that.’

Developing leaders

Standard Chartered invests significantly in leadership development programmes. ‘We focus a lot on the individual leadership journey,’ says Anton. ‘The demands of leadership have changed. The model of connected leadership is very relevant to us. Our leaders need to learn to navigate complexity.’

Authenticity and transparency are highly valued leadership attributes at Standard Chartered. Leaders are encouraged to align their own values with the values of the organisation. ‘I believe in being the best version of yourself,’ says Anton. ‘Authentic leadership speaks to that.’

Leadership development is focused on developing values-based behaviours as well as skills and capability. ‘Our organisation has a really unique position and opportunity to build on our purpose and mission,’ says Anton. ‘And part of my role is to help individuals at Standard Chartered to crystallise their own personal purpose in line with that, which is very exciting.’

The benefits of being connected

‘The quality of relationships internally and the relationships we build with clients and customers is a core part of who we are,’ says Anton. ‘We care about our people internally, and we care for our clients. Many clients tell us they stay with us because of our brand and our culture.’

Questions to ask yourself

Finally, here are some questions that you might find helpful to ponder a while before moving on to the next chapter. You may find it helpful to make a few notes as you think so you can refer back to them later in the book as you consider where to focus your efforts in becoming a more connected leader.

- What is our purpose as an organisation?

- Do I embody this purpose in the way I prioritise my time and attention?

- Are our vision and strategy clear and relevant to all of my colleagues?

- How could I actively encourage my team to focus more on the few things that are most likely to get us there?

- Which of the four stages above (involvement, making sense, tell the story and embed) would I improve if I could? What will I do about it?

Connected leader’s checklist

- Defining your purpose and direction needs to be an inclusive process, and it is only the start.

- Getting everyone bought into it is a longer job that needs care and persistence.

- Placing the customer at the heart of your purpose and direction sets a clear focus for your business.

- The companies that have a powerful shared sense of purpose and direction feel as though they are on a mission.

Notes

1 Sinek, S. (2013) ‘Start with Why’, TED talk video, www.youtube.com/watch?v=sioZd3AxmnE (accessed 16 June 2015).

2 www.providentfinancial.com/about-us/history/ (accessed 23 August 2015).

3 Weick, K. (1995) Sensemaking in Organisations, London: Sage, p. 409.

4 Weick, K. (1979) The Social Psychology of Organising, 2nd edition, New York: McGraw-Hill.

5 Coats, E. (n.d.) ‘Pixar’s 22 rules to phenomenal storytelling’, www.slideshare.net/llamallama/storytips?qid=3f4237a7-cbf9-43d4-b642-78340a54cdf6&v=default&b=&from_search=31 (accessed August 2015).

6 Schein, E. (2004) Organizational Culture and Leadership, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

7 Kaplan, R. S. and Norton, D. P. (1995) ‘Putting the balanced scorecard to work’, in Schneier, C., Shaw, D., Beatty, R. and Baird L. (eds) Performance Measurement, Management and Appraisal Sourcebook, Massachusetts: HRD Press, pp. 66–74.

8 Collins, J. (2001) From Good to Great, 1st edition, London: Random House Business.