Chapter 5

Values in action

This chapter is about authenticity, the second factor in connected leadership. It looks at the importance of creating a more authentic, values-led culture across your organisation in order to provide clarity to everyone about how you choose to behave and how this creates a unique customer experience. It also looks at how this translates at the personal level into what is really important to you as a leader and how that influences organisational performance as a whole.

I look at just what authentic leadership actually is and offer you a number of tools and techniques to help you assess your own values, including gauging your moral compass, increasing your self-awareness, deciding on your strengths and weaknesses in terms of emotional capital capabilities and increasing mindfulness practice.

There are insights that will help you to create a more values-led culture and consider your role as a significant role model in making this happen. I conclude by helping you discover just how ethical your leadership really is.

Redefining and aligning the core values

Shanthi had mixed feelings as she left the board meeting. She was the CEO of a large IT services firm in Mumbai and the financial results were good. The company had grown through acquisition over the last ten years at a phenomenal rate. It had exploited advances in new technology after every acquisition and was now one of the largest providers of IT services in the Asian markets.

But expansion had come at a price. Customer complaints were increasing and staff turnover was at a level that some board members felt was unsustainable. Shanthi worried that there was no real sense of what service meant any more at the company. In the early years it had been much easier. With a small central base, everyone knew each other (or at least knew someone who knew everyone else), but now the company resembled a house that had been extended several times in different architectural styles: there was little sense of a shared culture or consistent ways of doing things. Clients were starting to complain about the inconsistent levels of service, especially those that operated across several countries.

Shanthi was a person who cared deeply about service quality and client care. She knew what the business meant for the clients, and how much they relied on the business for their own operational effectiveness, but sometimes new colleagues who arrived because of an acquisition were not in tune with her ethos. Clients were beginning to indicate that they could no longer predict the level of service they were going to receive across locations and were turning to competitors whose service levels matched expectations. Another worry for Shanthi was that there were some ‘wild card’ employees at the company: people who were great at their jobs when dealing with clients but could get too involved in office politics and gossip and caused dissension among colleagues.

Shanthi believed that the best way to address the mixed customer experience and employee turnover issues was to redefine what the company stood for, its standards of behaviour and service, and to engage everyone on a journey to rediscover what made their business special. To do this she believed she had to make sure that her values and those of everyone in the business were fully aligned so that there was a clear and agreed code of conduct to which they were all committed.

What’s important around here?

The next factor in connected leadership, authenticity, is about how the business operates, about the culture and the values that actually drive behaviour in work. At a personal level it is about how you behave, based on your own values, and your personal authenticity as a leader. I am not talking necessarily about the values statement in your office or on your corporate website, I am talking about what is happening in reality. The actual values that are shared by you and your colleagues help to create the culture (how things work around here) and underpin the norms or assumptions1 on which the culture is based.

This is often a strong reflection of the character of the senior leaders and the principles on which they make decisions. If, for example, you and your colleagues make decisions and behave in ways that indicate that you prize integrity, then the culture is likely to reflect this assumption in the way people work with each other and with customers by people delivering on what they say they will do. It is essential to ensure that what you say you believe is important about mindset and behaviour is consistent with how you actually behave in practice. If you say you prize integrity (and possibly have it emblazoned on your corporate website and board room walls), but demonstrate that you prize success above all things, people are more likely to do whatever it takes to succeed rather than worrying about integrity. Longer term, the incongruence between what you say and what you do is likely to cause cynicism and reduced engagement among your people. This can lead to lower energy levels and commitment to performance. So it is important to be clear on what you value and to have a high level of congruence between stated and actual values in action if you are to have credibility and a motivated group of colleagues.

As we can see in Shanthi’s case, this is not always so easy to achieve in practice, and this problem can be exacerbated when companies have grown through mergers or acquisitions. In Shanthi’s business the underlying assumptions of each acquired business were not reviewed and there was no explicit process for reframing what was important to the whole company as each acquisition was brought on board. The end result was a company that resembled a patchwork quilt of different cultures, each allowed to continue with its own version of what was important, and the consequent impact of an inconsistent customer experience.

So if we want a great culture that leads to great employee and customer experiences we need to manage it with care. The culture is a result of the assumptions we all make every day about how things work around here. If, for example, I am a lawyer in a law firm where I believe that my personal values are something for me to keep to myself and that the priorities at work are always to maximise fees and to win cases for clients whatever it takes, I will leave my values at the front door and pick them up again, metaphorically, on my way home. The resulting culture, if my assumptions are shared across the firm, is likely to be one where billing is an obsessive competition between fee earners, where non-fee earners are treated as second-class citizens and where we will bend (or at least interpret broadly) the law if necessary to win every case.

Such a culture may well breed success, but at what price? Ultimately, this sort of cultural bias is likely to come back and haunt a company, as we have seen in cases across industries such as corruption in engineering, mis-selling in financial services, mis-reporting of outcomes in services provision to government and safety disasters in energy. The consequences can literally run into billions of pounds in damages and stock market value write-downs. I would suggest that corporate amorality, which often involves senior leaders turning a blind eye to cultural issues, is a costly business.

At the heart of the culture challenge is trust – trust between colleagues, between senior executives and colleagues, between customers and companies, between society and companies. When trust breaks down, as we have seen in some of the industries cited above, the fundamentals of business are broken. Trade and commercial enterprise operates well when there is a reasonable level of trust between parties, and when this is absent one’s ability to grow and prosper is ultimately held back.

The GlobeScan survey mentioned in Chapter 1 illustrates the scale of the problem when it comes to trust in business leaders today. Survey after survey underlines the overall decline in trust of those in power. Another study cited in Psychology Today found that there was a widespread perception that senior business leaders are dishonest, with almost 40 per cent of those surveyed saying that their supervisors failed to keep promises and just over a third saying that their supervisors blamed others to cover up mistakes or minimise embarrassment.2 This is little short of a crisis, which as leaders we need to address. In order to restore healthy levels of trust we need to focus more on how we lead and how trustworthy we are. As the role models for others we need to provide an authentic example in which they believe and have confidence.

Authentic leadership

So, how can we create a more authentic, values-led culture in our organisations? How can we create commercial success based on principle as well as pragmatism? If we draw on the wealth of research into authentic leadership that has been conducted over the past 15 years, we find that there are four aspects of authenticity that stand out: ‘self-awareness, a strong moral compass [based on clear values], balanced processing of information and open [trusting] relationships.’3

Much of the focus on leadership development over the last two decades has been on developing inspirational or transformational leaders. Authentic leadership represents a more inclusive and less individualistic style of leadership than transformational leadership: more in keeping with the shared process of connected leadership we will explore in subsequent chapters. The danger of placing so much emphasis on the inspirational leader is that it encourages a sense that all leaders should be heroic figures who ‘save the day’, as it were.

Organisations that rely on heroes can find succession challenging, and in my experience focus too much collective attention on the wishes of the hero rather than on building sustainable organisational capability. This is in line with the research which shows that building leadership as an organisational capability (rather than focusing on individuals) is a powerful source of differentiation and long-term performance, cited in Chapter 3.4

The impact of individuals should not be underestimated, however, as we see those throughout history who have had a significant influence on events, such as Winston Churchill and Nelson Mandela. But they are exceptions, and we could see them as being a product of their time. They were the leaders who crystallised or perhaps were even the product of a more widespread collective will, such as the British belief in freedom and resistance to Nazi oppression in the Second World War and the will of the South African black community to achieve self-determination and to overcome the oppression of the white government during apartheid.

In the networked, more democratic society in which many of us live now, overall leadership capability, which becomes an asset of your business, is more important to develop than individual leaders. When people act in concert (acts of shared leadership) they can achieve great things, such as the American civil rights movement in the latter part of the 20th century and the Polish ending of Soviet rule precipitated by the 10-million-strong Solidarity union when it started a revolution from the Gdansk shipyard in the early 1980s. Clearly, in both situations, there were individuals who helped catalyse the movement, with Martin Luther King and Lech Walesa respectively playing key roles. But the real momentum for change came from a wider base of concerted action by many individuals acting in a connected way.

All these historical examples also demonstrate the power of values in generating the will to challenge the status quo, and make changes happen in spite of overwhelming odds, in the name of freedom. The people involved were motivated, I would suggest, by a powerful cocktail of purpose, vision and values. They had a cause, a view of what needed to change, and they believed in shared principles of what was right (and wrong).

If, as leaders, we can be catalysts to a similar power surge, it is exciting to think what we might achieve. But we need to have three things on our side before this will happen:

- A clear purpose, a cause in which we all believe and a reason to accept personal risk.

- A vision of a better way, a sense of where we want to get to and, ideally, a credible strategy to get there.

- Agreement on what is right, and therefore what is wrong, and a shared moral code which inspires a desire to fight for these values when challenged.

We covered the first two in Chapter 3 and now we are exploring how to achieve the third. In each example above from 20th-century history we see a clear values-driven motive for change, a sense of injustice and a violation of human values.

A word of caution: if we approach this with a Machiavellian desire to manipulate the situation to achieve power and people’s commitment under false pretences, we will be found out and not trusted. In my experience, people have a good sense of when they are being manipulated and they don’t like it. We therefore need to be working from a position of personal integrity if we are to build trust and commitment in others. We need to be authentic.

The leader’s role: starting with self

It is difficult to change how an organisation behaves and operates without first making sure you are able to be the role model for that change. Gandhi’s quotations are well known on this subject: ‘You must be the change you want to see in the world.’ And: ‘As human beings, our greatness lies not so much in being able to remake the world – that is the myth of the atomic age – as in being able to remake ourselves.’5 Bringing it back to the here and now, if, for example, you want more agility but you slow down every decision by seeking more information or insisting on multiple levels of authorisation, you will demonstrate a lack of authenticity, in that you are asking for others to do something different that you are not willing or able to do yourself.

So, going back to the four attributes of authentic leadership mentioned earlier, it is helpful to reflect on where you are currently against each attribute – these attributes are summarised in Table 5.1.

table 5.1 Attributes of authentic leadership

| Attributes | Description |

| Strong moral compass | Having a clear sense of what is right and wrong and the will to act accordingly. |

| Self-awareness | Understanding yourself in terms of what drives your behaviour and what effect you have on yourself and others. |

| Balanced processing of information | Being able to make sense of information without bias and to accommodate the views of others in order to arrive at a balanced interpretation of data and events. |

| Open and transparent relationships | Sharing information freely with others and being open to learning in a straightforward way. |

Being a leader who demonstrates these attributes can create a series of benefits for your organisation. Research shows that it encourages a positive culture in which people are motivated to give of their best, increasing levels of employee wellbeing, which encourages engagement and people feeling more competent, which, in turn, leads to improved productivity and people choosing to take increased responsibility.6

But first you need to ensure you are personally strong on all four attributes. You can review the first two attributes in this chapter and the second two in Chapter 6.

1 What is my moral compass?

How do you know what your personal values are? What’s really important is that you are clear in your own mind what are the principles and preferences you hold dear and which you are not willing to compromise, or if you do it will challenge your sense of integrity. Your values are likely to be a result of life factors such as your personality, your beliefs, your early life experience and experiences along the way, as well as physiological factors such as your drive for survival or pleasure. Your values influence the choices you make and your opinions on what is good, right or of value. Here is a simple way to define (or refine if you already have a list) your values.

Stage One: Consider what is really important to you

Please consider the four questions in Table 5.2 in both your personal and work lives and write down your answers to each one. Please be as forthright with yourself as you can be.

table 5.2 What is important to you?

| Question | In your personal life | In your work life |

| 1 Think about the decisions in your life of which you are the most proud. Why do you feel so proud? | ||

| 2 Think about decisions you regret. Again, why do you regret them? | ||

| 3 Think of the situation when you have been at your happiest. Why did that make you happy? | ||

| 4 Think of the situation when you have been most frustrated. Why did that make you frustrated? | ||

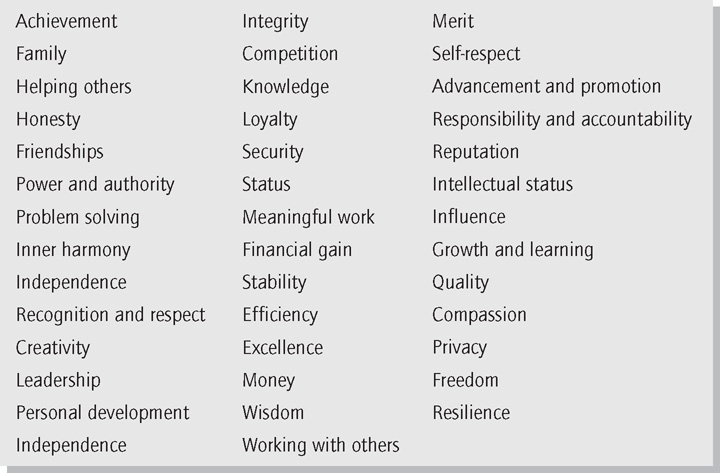

You might find some of the words in Figure 5.1 helpful if you are getting stuck. (Some of these overlap, and that is fine as different nuances may appeal to you in different ways.)

Stage Two: Create a short list

Now list the five or ten key principles or values that are suggested by your responses to Stage One. Choose words or short phrases that make sense to you. Read through the list to see whether you think anything is missing and if it is, add it to the list. If one or two are saying the same thing to you, combine them into one.

Stage Three: Prioritise

Put each value on a separate card or piece of paper and start putting them in order. Put the one or two that are most important to you at the top and the ones you are less passionate about at the bottom. Place the others in between. Keep sorting them until you have them in the right order for you. If you get stuck, select two and consider which is more important to you. It can be helpful to consider a challenging decision you might need to make (such as whether to move job) and ask yourself which value would be most critical in making the decision. Put that one above the other in your list. When you are comfortable that a) you have the list in the right order and b) you have removed any duplicates, choose the top three.

Stage Four: Articulate

The final stage is a good test of whether or not you have identified your true values. Take the top three and write them into a sentence beginning: ‘In my life the most important values for me to live by are . . . ’ Does this sentence ring true? If not, edit it until it does. If the fourth value is still really important and helps make the sentence true for you, add it back in.

Then tell at least two other people in order to find out if you are comfortable with the sentence. Choose a work colleague and a personal friend or family member, so that you can test your values in both work and non-work contexts. Again, if they don’t feel right, edit them until they do.

Now you have a definition of your moral compass: the values that you are driven by and which you will not compromise. They summarise the principles that are really important to you in your life. By the way, if you have done this exercise but feel that you would be willing to compromise the values you ended up with, please have a good look at yourself in the mirror and ask yourself whether you are really being true to yourself. In my experience, if you are willing to compromise your values you may be a pragmatic person who believes that the end justifies the means. But until you define the principles by which you live your life I suspect you will not be someone who inspires a high degree of trust and loyalty among other people. Being pragmatic when it comes to values makes it difficult to be authentic.

There are several ways you can now choose to use your moral compass, which might be helpful as you become a more connected leader. For example, you could compare your personal values with those of the organisation for which you work (in practice rather than necessarily what is in the corporate values statement). Are your values and the organisation’s cultural values congruent or can you see significant differences that concern you? If the latter, how can you reconcile this?

You could repeat this activity with your team and open up a discussion about how to align your values as people and with the organisation, so that you can appreciate what preferences others have and seek to accommodate these in the way you work together. (We will discuss this further in Chapter 8 when we look at collaborative achievement.)

You may also find it helpful to discuss your values with your partner or closest friend to explore how they see how your values affect them and whether this is in a positive or negative way. It can be both. For example, if you value independence highly this may make you a stimulating person to live with and at the same time make you frustrating in your lack of sharing. Through the discussion you might find that the increased understanding between you is helpful and enables you to explore ways to reduce the negative effects of your values on the other person. The conversation would be richer if you were both sharing your personal values and exploring how you complement each other or how you might need to accommodate the other person’s preferences more carefully.

2 How self-aware am I?

Having a clear moral compass, or set of personal values, is an important part of being self-aware. If you know what drives your choices you will be more able to manage your decision making and interaction with others to achieve optimal outcomes. Another part of self-awareness is about understanding the impact you have on other people.

I am a big believer in the idea that we all choose our mood. When a leader walks in through the door or picks up the telephone or sits down at a meeting, they are sending cues to everybody else about what they think is important. As a leader you need to think of yourself as being in a goldfish bowl where you are observed and your behaviour is constantly interpreted. Obviously the more senior you are, the wider this applies, but the team leader in the call centre or the manager in a distribution unit also represents the organisation’s actual values and leadership ethos and demonstrates what everyone else will interpret as what’s important around here.

Being an effective and authentic leader requires a good degree of self-awareness, which is part of what we now call emotional intelligence. The concept of emotional intelligence has gained much prominence over the last few years. Emotional intelligence is the ability to be aware of one’s own and other people’s emotions as a guide to how to manage your thinking and behaviour in order to improve relationships with others and outcomes.

Those with higher emotional intelligence typically have better mental health, are more effective at their jobs and are better able to lead others.7 Once you have gained an understanding of yourself and why you act as you do, emotional intelligence is about the self-awareness to manage your reactions rather than have your reactions manage you. It is the key to being able to behave effectively even in pressurised situations where you find yourself tempted to ignore your best intentions.

A useful framework for looking at emotional intelligence for leaders is the Emotional Capital model (see Emotional capital capabilities, below) developed by RocheMartin, a publisher of emotional intelligence profiles.8 It looks specifically at the capabilities leaders need to demonstrate high levels of emotional intelligence in their roles, based on a meta-analysis of research in this area.

Emotional capital capabilities

- Self-knowing: the capacity to recognize how your feelings and emotions impact on your personal opinions, attitudes and judgements.

- Self-confidence: the ability to respect and like yourself and be confident in your skills and abilities.

- Self-reliance: the emotional power to take responsibility for yourself, back your own judgements and be self-reliant in developing and making significant decisions.

- Straightforwardness: the ability to express your feelings and points of view openly in a straightforward way, while respecting the fact that others may hold a different opinion or expectation. Being comfortable to challenge the views of others and to give clear messages.

- Self-actualisation: the ability to manage your reserves of emotional energy and maintain an effective level of work/life balance. Thrive in setting challenging personal and professional goals and your enthusiasm is likely to be contagious.

- Relationship skills: the knack for establishing and maintaining collaborative and rewarding relationships characterized by positive expectations.

- Empathy: the ability to grasp the emotional dimension of a business situation and create resonant connections with others.

- Adaptability: the ability to adapt your thinking, feelings and actions in response to changing circumstances. Being tolerant of others and receptive to new ideas and considering different points of view.

- Self-control: the ability to manage your emotions well and restrain your actions until you have time to think rationally. Being able to stay calm in stressful situations and maintain productivity without losing control.

- Optimism: the ability to sense opportunities even in the face of adversity. Being resilient, seeing the big picture and where you are going and being able to focus on the possibilities of what can be achieved.

Newman7

This range of capabilities is a challenging mix and typically I find that leaders are stronger on some than others. There are at least three lessons you can take from this.

- The first is to play to your strengths, so that you build from where you are already competent. But it is important to be aware that overdone strengths can derail performance, such as when self-confidence becomes arrogance and an unwillingness to listen to dissenting views.

- The second is to become more effective in areas of weakness as these may be blind spots in your behavioural repertoire and hold you back. If, for example, you tend to be low on empathy, you may appear aloof and forget to recognise that other people’s emotions are important.

- The third is to build a team with a blend of capabilities and to value the differences so you can be complementary to each other. Having colleagues in your team who are high on empathy, in the case above, will keep you as a team tuned into how others are feeling and therefore how best to engage and motivate them.

This was the case with one executive team I was working with where the CEO was high on self-confidence and self-reliance but low on empathy and relationship skills. She was a real driver of performance and led from the front. She was not, however, so good at taking everyone with her. Fortunately, in her team there were two colleagues who were strong on empathy and these were often the people I would ask to describe for their colleagues what impact the decisions the team took might have on other people in the business.

Once the CEO realised how this question was helping rather than hindering progress, she was more receptive to it being discussed by the whole team. The empathetic colleagues felt more valued and that their views were more valid, the team’s performance improved and their impact in the business was more effective as they engaged the wider business on a major transformation programme. And the CEO became more self-aware through this process and took this insight with her into her other dealings with colleagues, checking in with others about how they felt about things in a way that added greatly to her credibility and influence.

Understanding our emotional capital can therefore enable us to manage others in a more authentic and effective way that is typically more in line with the organisational values. Emotional intelligence underpins the leader’s role in creating a values-based organisation because the leader’s behaviour is an important manifestation of what those values are in practice.

3 Mindfulness

Mindfulness is the practice of being more present in the world which psychologists have derived from the Buddhist religion to help people be more aware of their emotions. Mindfulness aims to help leaders build their resilience and deal more successfully with stresses in their working lives.

Mindfulness is very fashionable at the moment, with any number of apps, web courses and books to help you learn to concentrate on the ‘now’ for better mental health and thus help, it is claimed, psychological flexibility, awareness, resilience, better decision making, performance and learning. It is related to situational awareness, discussed in the next chapter.

A number of prominent companies now offer mindfulness programmes for employees, including Apple, Procter & Gamble and McKinsey, where it is felt that people can become more productive by stepping aside from the busyness of their working day and taking a few moments to clear their minds.

Here are a few really thought-provoking tips from Leo Babauta which you can use to help you deal with everyday stresses and to be more authentic in your interactions with yourself and others.9

- Do one thing at a time. Single-task, don’t multi-task. When you’re pouring water, just pour water. When you’re eating, just eat. When you’re bathing, just bathe. Don’t try to knock off a few tasks while eating or bathing or driving. A Zen proverb says: ‘When walking, walk. When eating, eat.’

- Do it slowly and deliberately. You can do one task at a time, but also rush that task. Instead, take your time and move slowly. Make your actions deliberate, not rushed and random. It takes practice, but it helps you focus on the task and do it well.

- Do less. If you do less, you can do those things more slowly, more completely and with more concentration. If you fill your day with tasks, you will be rushing from one thing to the next without stopping to think about what you do. It’s a matter of figuring out what’s important and letting go of what’s not.

- Put space between things. This is related to the ‘Do less’ rule, but it’s a way of managing your schedule so that you always have time to complete each task. Don’t schedule things close together. Instead, leave room between things on your schedule. That gives you space in your schedule in case one task takes longer than you planned and for important but unplanned discussion.

- Spend at least five minutes each day doing nothing. Just sit in silence. Become aware of your thoughts. Focus on your breathing. Notice the world around you. Become comfortable with the silence and stillness. It will do you a world of good.

- Stop worrying about the future. Focus on the present. Become more aware of your thinking. Are you constantly worrying about the future? Learn to recognise when you’re doing this and then practise bringing yourself back to the present. Just focus on what you’re doing, right now. Enjoy the present moment.

- When you’re talking to someone, be present. How many of us have spent time with someone but have been thinking about what we need to do in the future? Or thinking about what we want to say next, instead of really listening to that person? Focus on being present, on really listening, on really enjoying your time with that person.

In the hurried, overloaded world in which we live, with so many friends on Facebook and contacts on LinkedIn, these suggestions are a helpful reminder that the quality of connections we make is more important than the number. Less is more.

Creating a values-led culture

Moving back to the organisational point of view, it is helpful to consider how to create a values-led culture, or perhaps more accurately, how to increase the extent to which your culture is values-led. The reason this is so important is that having shared values across the business gives a clear point of reference for each person and team on how to behave, which ultimately influences how your customers experience dealing with your organisation on a day-to-day basis.

Your values, if they are lived out in the culture of the organisation, will give people a shared code of conduct as a basis for increased empowerment, collaboration and learning. This code provides clarity on what the organisation’s preferences are, what is right in each particular situation that people find themselves in, so that people can make decisions based on a consistent set of principles driving consistent behaviour and outstanding performance – both for your business and for your customers.

If you combine this with what we looked at in the last chapter, having a clear shared sense of purpose and clarity of direction, you have a powerful framework for people across your organisation within which to make connected leadership practical and valuable. As a leader you are enabling the organisation to connect, to make devolved decisions in a coherent way, to collaborate across functions and business units in a joined-up way to accelerate end-to-end process efficiency, to share and adapt to changing circumstances with a shared intelligence and to do the right thing by the customer. It is a freedom framework.

In my research I found that this framework was a pre-requisite to successful introduction of these other ways of working. Without it they were at risk of being counter-productive because people didn’t have the clarity of purpose, vision, strategy and values within which they can operate with higher degrees of freedom without losing their cohesion and effectiveness. Having a strong and shared vision, purpose and values provides a rational and emotional framework for ‘ensuring careful coordination of effort in a common cause’,10 that is the direction for shared strategy and action, a clear sense of meaning and a clear code of conduct.

Values-based leadership provides the behavioural framework to guide people across the organisation to achieve the vision and purpose in a principled and morally satisfying way. In combination, these factors give clarity for everyone on the organisation’s ‘mission command’,11 leaving them free to operate knowing they are not acting or behaving inconsistently with the overall aims and values of the wider organisation.

Except in extreme cases such as, perhaps, totalitarian regimes, it is difficult to impose shared cultural values. Cultural values emerge and evolve over time, and as leaders we are better focusing our effort on encouraging those values to grow in the direction of the light we desire by ensuring that the light is clear, appealing and relevant to our shared context.

Take, for example, the mobile operator in the UK, EE, which was formed from the merger of T-Mobile and Orange in the UK. EE articulated ‘Be Bold’ as one of its shared values post-merger. Being bold is clear – it is simple and demands a certain type of behaviour, it is appealing to many because it is aspirational and suggests an exciting ride, and it is relevant because the mobile sector is highly competitive and in a post-merger situation EE needed to establish itself quickly as a positive brand in consumers’ minds. So it has resonated well with employees and it is helping EE to create a shared culture of ambition, action and courage, which are characteristics helping it to compete effectively.

So how does a company like EE achieve a healthy level of commitment from across the workforce to this and other statements as shared values? The answer is inevitably varied, but I suggest that there are two ways in which you can review how embedded your organisational values are in practice, by thinking through the following aspects of values in action: having clarity about what your values mean and having leaders who are genuine role models of them day to day.

1 Clarity of values

Research indicates that the process of clarifying personal and organisational values itself has a positive impact on levels of commitment to the organisation.12 Those people with a high level of clarity about their personal values as well as the organisational values have the greatest commitment to the organisation. However, the research also indicates that simply clarifying the organisation’s values does not automatically inspire commitment: it is also important for individuals to clarify their own values vis à vis those of the organisation. It is the act of connecting personal and organisational values that leads to increased commitment and performance.

Values inform our decisions. They guide our actions in an environment characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA). They are therefore empowering. As a leader it is important to find your own values, to identify them and live by them. As a leader it is also important to enable others to clarify their values and allow them to live to those values within the context of the cultural values of your organisation.

An authentic leader starts by ensuring there is clarity about the organisation’s values, or if there is not, as possibly in the case of a post-merger integration, developing them with everyone in the business. The values need to be described in a way that resonates with people throughout the organisation, at all levels. It is less effective for leaders to tell people what principles to operate by; it is more productive to use a collaborative process to develop or refine your company values, if they are not already in place. The discussion should include all stakeholders (customers, colleagues, investors and so on).

The shared values need to be reflected in the way you and your peers as leaders behave: the climate you create around you, the interactions you encourage managers to have with their teams, how decisions are made and so on. By being true to your values and balanced in your approach, you can engender an environment characterised by trust and respect. This establishes your ability to delegate, collaborate and lead change effectively, which we will explore later in the book.

As we discussed in the previous chapter, purpose and direction are about what the organisation does to define its mission in the world. This then gives meaning to people’s lives when they come to work every day. It is future-orientated: where we as an organisation are going and why.

Authenticity embraces how the business operates today: its culture, behaviour and how decisions are made. It is about creating an environment based on values such as trust and respect. If you operate on the basis of moral pragmatism it will be difficult to develop a culture of trust and respect. Determining these values and embedding them into the organisation’s DNA are fundamental to the development of the connected business. If there is any sense of mistrust or the priority of individuality over collective effort, or the perception of the hoarding of power, then the other factors will be almost impossible to implement.

The first step in this transition is to decide how to explore and make sense of your cultural values in a way that resonates with people in the organisation and acts as a helpful guide. This should colour every aspect of the business, such as how the values influence every touch point of the employee experience, from recruitment and retention to compensation and benefits. This will help everyone be clear about the criteria for success.

If the criteria encompass only the end result – ‘you must achieve the target of X by Y date’ – and there is no reference to the means, then why should anyone worry about how they achieve the end result? It is also, for example, important to embed your values and the associated behaviours in how people’s performance is managed, as a balance to their task outputs.

2 Leaders as role models

This alignment between the individual and the organisation’s values is critical. When I worked with a major international bank which wanted to return to the deeply ethical, deeply caring values of its pioneering founders, we ran workshops with senior leaders in which we looked at the values through a series of moral dilemmas: how would people act in a certain situation, did they know what to do immediately or did it take a while, what could they take away from this? The research that came out of this showed that people had a very different attitude to moral decisions in work compared with what they felt was the right thing to do at home.

It was almost as if, at times, people would lose that sense of an inherent morality within themselves, and the person that would show up for work wasn’t the same person who got out of bed in the morning. We helped leaders to bring those two sides of themselves back into alignment to make sure the values being advocated by senior leadership took root throughout the wider managerial team.

Leaders need to be genuine role models while being openly intolerant of behaviour that demonstrates the opposite of the values. So if integrity really is paramount in the organisation, the way all senior managers behave must reflect this. If anyone fails to do so, the leader has to have the courage not only to challenge them but eventually take steps to part company with them. I recall the head of a major retailer standing up at an event for his top 50 directors soon after he took over the company and making it plain that if anyone didn’t believe in the company’s values they were in the wrong business. People have to understand by deed as well as word just what is appropriate, make sense of it and internalise it so that it comes to seem authentic for them.

There is a strong link between values, culture and engagement. The MacLeod report into engagement, sponsored by the UK government and published in 2009, draws on a wide range of sources and concludes that there are four main drivers of employee engagement:13

- Leadership which ensures a strong, transparent and explicit organisational culture which gives colleagues a line of sight between their job and the vision and aims of the organisation.

- Engaging managers who offer clarity, appreciation of colleagues’ effort and contribution, who treat their people as individuals and who ensure that work is organised efficiently and effectively so that colleagues feel they are valued, and equipped and supported to do their job.

- Colleagues feeling they are able to voice their ideas and be listened to, both about how they do their job and in decision making in their own department, with joint sharing of problems and challenges and a commitment to arrive at joint solutions.

- A belief among colleagues that the organisation lives its values, and that espoused behavioural norms are adhered to, resulting in trust and a sense of integrity.

This summary includes reference to the organisation (culture and values), the manager, the work itself and the ability of the employee to influence the organisation. As a leader a key part of your job (along with your leadership colleagues) is to unify these factors and to create for each colleague a powerful experience that is engaging and that drives productivity and responsibility. The first factor describes you as role model, the second describes the wider management population and the criticality of the line manager relationship for employee engagement, the third asks you to listen well and the fourth is about living the values in practice. It sounds easy, and at one level it is relatively simple.

The difficulty comes when you need to choose between these priorities or other business tasks which seem more urgent and important. I have had the privilege in recent years to work with several CEOs who have made the call that these priorities are in fact more important than many other possible areas of attention, and who lead highly successful businesses. Instead of focusing primarily on what some might see as more ‘strategic’ issues, such as doing deals or managing the details of finance or sales, they have invested their time in their people, in their leadership teams and in the culture of their organisations. One turned his company from the most complained about in the industry to the least, another boosted international growth and profitability by double digits in a time of recession. Their businesses are highly engaged and highly successful, with increased shareholder investment.

Unilever’s chief executive, Paul Polman, gave a wide-ranging interview to the McKinsey Quarterly on the lessons he has learned about leadership success during his career at three major consumer goods companies.14 Asked to isolate a key lesson that he has learned as a manager, he replied:

‘I think the first thing is (to be) purpose driven and (to have) values – that, I think, is very important. And (what) I think over my career is, if your values, your personal values, are aligned with the company’s values, you’re probably going to be more successful longer term than if they are not. If they are not, it requires you to be an actor when you go to work or to be a split personality. If these values are totally aligned [you’re in a good place]; we all know that work–life balance has more and more become a life balance of which work is a part. So it’s very, very important.’

Ethical leadership

A final word on values. If you are looking for ways to increase the levels of authenticity in your business, it is helpful to consider how ethical your leadership practices are. Ethical leadership is closely related to the idea of authentic leadership. Kalshoven et al.’s 2011 ‘Ethical leadership at work’ questionnaire gives a helpful checklist for what ethical leadership means.15 Table 5.3 illustrates the appropriate behaviours.

table 5.3 Ethical leadership checklist

| Ethical leadership at work dimension | Description | |

| Fairness | Do not practise favouritism, treat others in a way that is right and equal, and make principled and fair choices | |

| Power sharing | Allow followers a say in decision making and listen to their ideas and concerns | |

| Role clarification | Clarify responsibilities, expectations and performance goals | |

| People orientation | Care about, respect and support followers | |

| Integrity | Consistency of words and acts, keep promises | |

| Ethical guidance | Communicate about ethics, explain ethical rules, promote and reward ethical conduct | |

| Concern for sustainability | Care about the environment and stimulate recycling | |

Source: Kalshoven et al.15

If you rate your organisation or team on these dimensions currently (from good to bad) it will highlight where you can increase the level of ethical maturity, which in turn will support the shift to creating a truly authentic business. I’d encourage you to do it by yourself and with your team to explore ways to increase the way ethical leadership is played out in practice and to act on the findings.

case study

Values and authenticity at Marks and Spencer

Over the last 130 years, Marks and Spencer (M&S) has grown from a single market stall to become an international multi-channel retailer, operating in over 50 territories worldwide and employing more than 85,000 people. The company’s founding values are quality, value, service, innovation and trust. Today these have evolved into Inspiration, In touch, Integrity and Innovation.

Embedding enduring values

The ‘Plan A’ ethical and environmental programme, launched in 2007, has become part of the fabric of the business. This programme, which engages employees, suppliers and customers, is constantly updated as M&S aims to become the world’s most sustainable retailer: sourcing responsibly, reducing waste and helping communities.

Tanith Dodge is director of HR at M&S. She believes that the importance of strong values to business success has been a critical lesson from the global economic crisis. ‘Doing the right thing matters more than ever,’ she says. ‘Values and authenticity need to be at the heart of the business. Leaders need to have integrity and build cultures of trust alongside the whole corporate social responsibility agenda.’

Building leadership capability

The M&S values also inform the organisation’s approach to leadership. The business has been through significant change in recent years in response to the changing needs of customers and the challenges of the economic downturn. As part of its transformation programme, M&S has focused on building the capability of senior leaders to take the business forward in today’s increasingly competitive and unpredictable marketplace.

To achieve this, M&S has developed challenging and innovative leadership development programmes which encourage an increasing focus on the customer. All learning and development is underpinned by M&S’s unique ‘ways of working’ – agility, collaboration, entrepreneurialism and simplicity.

The principles of Plan A are also embedded in leadership development programmes as M&S works with charity partners and community groups to provide mutually beneficial learning opportunities. Many of these opportunities are disruptive – they challenge leaders to address uncomfortable situations, which encourages new ways of thinking. This leads to greater innovation back in the workplace.

M&S has further moved away from traditional classroom-based learning with the introduction of digital technology, such as interactive portals where leaders can collaborate, learn and manage their own development journeys.

‘We have built more connected leadership across M&S as we develop the capability of leaders in line with the values and attributes at the heart of the M&S brand,’ says Tanith. ‘Forming these meaningful connections has galvanised leaders to lead change and has also resulted in increased productivity and cost savings.’

Living the shared purpose

Tanith is also passionate about the importance of a shared purpose in order to create a seamless customer journey: ‘You’ve got to have a shared purpose and direction so that all parts of business are joined up and there is a strong coalition behind driving results. This shared purpose doesn’t just come from the top. It comes from across the entire business. We want customers to have the same positive experience whether shopping online, mobile, or in store. In our digital age, customers expect an agile response wherever they are. We’re living in unprecedented times. Everything has speeded up.’

In addition, M&S has developed a set of behaviours that sits alongside its core values. ‘We’re passionate about what we do,’ says Tanith. ‘We really believe in doing the right thing, so integrity and trust are absolutely key. Our culture of collaboration comes from shared values, shared purpose and direction, devolved decision making, good communication and engaged employees who feel empowered.’

Finally, here are some questions that you might find helpful to think about before moving on to the next chapter. You may find it helpful to make some notes to refer back to later as you consider where to focus your efforts in becoming a more connected leader.

- What kind of leader do I want to be?

- How does that align with our organisational purpose and direction?

- Do I have an honest understanding of my values and what motivates me?

- Can I describe the relationship between myself as a leader and others in the organisation?

- Is there alignment between my behaviour and my leadership objectives?

Connected leader’s checklist

- How we do things determines whether people trust us or not – as leaders and as organisations – just as much as what we do

- By being clear and uncompromising about our values we are able to demonstrate standards of behaviour in which others can have confidence

- Understanding our emotional intelligence also helps us manage ourselves in line with our values and in a way that others can trust.

Notes

1 Schein, E. (2004) Organizational Culture and Leadership, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

2 Williams, R. (2010) ‘The erosion of trust and what to do about it’, Psychology Today, 26 December, 1, www.psychologytoday.com/blog/wired-success/201012/the-erosion-trust-and-what-do-about-it (accessed 16 June 2015).

3 Walumbwa, F., Avolio, B., Gardner, W., Wernsing, T. and Peterson, S. (2008) ‘Authentic leadership: development and validation of a theory-based measure’, Journal of Management, 34(1), 89–126.

4 Ulrich, D. and Smallwood, N. (2006) How Leaders Build Value: Using people, organization, and other intangibles to get bottom-line results, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

5 From ‘Gandhis-top-10-fundamentals-for-changing-the-world’, www.positivityblog.com (accessed 17 June 2015).

6 Ryan, R. M. and Deci, E. L. (2001) ‘On happiness and human connections: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being’, Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

7 Newman, M. (2008) Emotional Capitalists, Chichester: RocheMartin.

8 Newman, M. and Purse, J. (2011) ‘Emotional Capital Report,’ Melbourne: RocheMartin.

9 Babauta, L. (2009) ‘The mindfulness guide for the super busy: how to live life to the fullest’, http://zenhabits.net/the-mindfulness-guide-for-the-super-busy-how-to-live-life-to-the-fullest/ (accessed 16 June 2015).

10 Leithwood, K. and Mascall, B. (2008) ‘Collective leadership effects on student achievement’, Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 529–561.

11 Bungay, S. (2011) The Art of Action, Boston, MA: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

12 Posner, B. Z. and Schmidt, W. H. (1993) ‘Values congruence and differences between the interplay of personal and organizational value systems’, Journal of Business Ethics, 12(5), 341–347.

13 MacLeod, D. and Clarke, N. (2009) ‘Engaging for success: enhancing performance through employee engagement’, A report to government; http://www.engageforsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/file52215.pdf. London: Office of Public Sector Information.

14 McKinsey & Company (2009) ‘McKinsey conversations with global leaders: Paul Polman of Unilever,’ McKinsey Quarterly, October, 7.

15 Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D. and De Hoogh, A. (2011) ‘Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): development and validation of a multidimensional measure’, The Leadership Quarterly, 22(1), 51–69.