Chapter 6

Connected relationships

In this chapter we will explore how your authentic leadership plays out in terms of the strength of your relationships at work. We start by looking at how you can achieve more open and transparent relationships and thus improve your relationship-building qualities through:

- applying emotional intelligence

- leading with purpose

- understanding how you come across

- opening up to others

- the power of feedback.

The final element of authentic leadership is balanced processing of information. This guides you through the concept of situational awareness, having honest conversations and managing conflict effectively. I leave you with questions to help you map your key relationships.

Mohammed sat in his car in the car park at work, gripping the steering wheel and staring out of the windscreen into space. His frustration was boiling over again and he couldn’t understand why his colleagues were so sensitive. He ran through the events of this afternoon in his head.

He had gone to the website project review meeting in a good mood, hoping for a positive discussion about progress with the new website and happy to help his team members to resolve any problems they had. He had told them repeatedly that the deadline could not move, and he had been consistent in his view that the timescales were achievable.

When he got to the meeting with John, the project manager, and Mary, the lead developer, he found that they were at least two weeks behind schedule and expecting this to get worse over the coming weeks. John kept on talking about scope creep and Mary seemed to be preoccupied with how her team members were feeling under pressure. Mohammed tried to be clear with them, but they didn’t seem to be listening to him. When he raised his voice a little to make his point clear, John went quiet and Mary stared at the floor. They appeared to be upset, which seemed ironic to Mohammed as he was the one who should be upset. He told them to sort it out and the meeting ended after only half an hour.

This project was important to Mohammed, and to the whole team, as it was high profile and he knew that the CEO was personally interested in seeing the website launch happen in time for the peak trading period. Yet he felt that neither John nor Mary really understood this and that they left the meeting no more committed to it than when they’d started. Mohammed sat in his car and wondered how he was going to get through to these people.

Looking outward

In the previous chapter we looked at how shared values drive behaviour, which in turn drive culture, performance and the customer experience. As a leader you at least partly set the tone for others, and if you can influence those around you so that you share a positive set of values, it is far more conducive to creating a customer-centric culture. I say ‘partly’ because the optimal situation is where there is a mutual expectation between you and your colleagues of standards of behaviour that reflect the type of business you all want to work in.

If, for example, you all value great design quality and you don’t tolerate in each other behaviours that get in the way of outstanding design, you will be connected in your approach to work and more likely to inspire each other to achieve breakthroughs in design. As leaders, therefore, our role is to enable this to happen, rather than seeing ourselves as the sole guardian of the values.

As we saw in the last chapter, if you do not embody the values in your day-to-day behaviour, it will be difficult for others to do so, thus eliminating the possibility of shared values. But if we are clear about what’s important and are self-aware enough to manage ourselves in line with those values, we have a chance to create the environment where the values are a shared foundation for a great culture.

In this chapter we move that on to the next two aspects of authentic leadership: establishing open and transparent relationships and balanced processing of information. I will give you some techniques to help you examine the effectiveness of your relationships with others. I will also look at how you can create an open and honest culture by establishing relationships that are based on welcoming opposing viewpoints and fair-minded consideration of those viewpoints as part of processing information in a balanced way. As a connected leader you need to draw out from others what is important and how to make it work in practice rather than typically imposing your own will and knowing best.

Why is this important? Connected leadership relies on high levels of trust between customers, colleagues and leaders. In its Global Workforce Study, consulting firm Towers Watson found that 79 per cent of employees rank trustworthiness as the number one leadership attribute.1

Developing open and transparent relationships

1 Developing your emotional intelligence in relation to others

In the previous chapter we discussed the importance of emotional intelligence and being aware of your own values and emotions to guide your thinking and behaviour. We are now going to turn to two other components: social awareness, or your ability to understand what’s really going on with other people emotionally, and relationship management, or your ability to use awareness of your emotions and those of others to manage interactions successfully. Both are key to building and sustaining high levels of trust.

Building on the review of your emotional capital capabilities in Chapter 5, it is helpful to sharpen your emotional antennae regarding relationships. In my experience it is a long process of gradual discovery to see and accept yourself as others see you. It is one that takes repeated feedback, discussion and reflection with those around you, especially those you trust. There is, at least for some people, an inherent contradiction here because as a leader you are demonstrating on a daily basis a willingness to stand out and to take responsibility and accept the risk of failure. Yet, at the same time, you need to have the humility and selflessness to listen to how others perceive you and appreciate how your behaviour affects them, even though you may have in your own mind a good reason for such behaviour. The prize for achieving this is worth the effort. You can start by asking yourself questions such as:

- How do you understand what makes you and others tick?

- How often do you ask for feedback from others?

- What happens to your mood and behaviour under pressure?

- What tactics help you in these situations to remain calm and self-controlled?

- How much time do you spend each week reflecting on your personal effectiveness as a leader?

- How willing are you to address conflict in a constructive way in the best interests of both the business and the people involved?

It is likely as a leader that you already have considerable competence in relationships, but it is helpful to read these questions and to ponder a while on your answers, because they may suggest ways for you to increase your competence in relationships even further. They can help you coach yourself.

Improve team engagement

It can be very productive to work with your team to explore how to improve your engagement with each other and encourage others to feel positive and valued. Try the following activity with the team as a way to increase trust and know each other better to aid performance.

First, ask people to put their rational minds to one side for a while. Then ask them to answer all or a selection from the following questions:

I love it when . . .

I’m at my best when . . .

I feel valued when . . .

I’m energised when . . .

I’m at my worst when . . .

I feel frustrated when . . .

I’m happiest when . . .

I’m intimidated when . . .

I feel fulfilled when . . .

You can discuss each question in turn so that you all hear each other’s answers to the same question. This can then lead to more in-depth discussion. Or each person can share all of their answers in one go, so you develop a better understanding of each person in turn. You can make it into a game by writing each question on a separate card and turning over a card at random to discuss among the team. The key objective, whichever way you approach the activity, is to gain a much closer understanding of what makes each of you tick, which is helpful when thinking about a particular issue or problem since it gives each of you fresh insight into what is important to others.

You can also include these questions in discussions with colleagues to develop more open dialogue and share your views as well as listening to the other person’s. In 25 years of working with senior leadership teams I have rarely come across a team that naturally and regularly has discussions of this nature. It often takes specific team-building workshops for these questions to be answered honestly and in any depth, and teams typically find it difficult to continue to have such open discussions when they are back in the routine of work. But I find that leadership teams that do develop the skill of open dialogue and honest disclosure of emotional as well as rational task information accelerate to higher levels of trust, coherence and performance. We will discuss how you can develop your team to be more connected in the next chapter.

Understanding and using your feelings

Developing stronger emotional literacy enables you to have more useful conversations that explore feelings as well as objective facts with your colleagues, customers and other stakeholders. But first you should make time to reflect on your own feelings so that you understand them and are able to describe them accurately. For example, try using a three-word sentence beginning with ‘I feel . . . ’ Interestingly, we sometimes use ‘feeling’ words to describe thoughts, such as ‘I feel like . . . ’ or ‘I feel as if . . . ’ which often describe what we are thinking. So try to distinguish between thoughts and feelings to avoid confusion. When describing your feelings start with ‘I feel . . . ’ followed by an emotion adjective such as angry, hurt, happy or pleased.

It is also helpful to label feelings rather than labelling people and situations, using statements such as ‘I feel impatient’ instead of saying ‘This is ridiculous’ and ‘I feel hurt’ instead of ‘You are insensitive’. In this way you are articulating your feelings effectively and without suggesting fault in others. It is very important that you take responsibility for your feelings by how you describe them. ‘I feel frustrated’, for example, is more helpful than ‘You are making me frustrated’.

You can use your feelings to set and achieve goals. Answering ‘How will it feel if I do this?’ and ‘How will it feel if I don’t?’ sets up emotional connections to your goals, and you can do the same with others by asking them ‘How do you feel now?’, ‘How will you feel when we achieve this?’ or ‘What would help you feel better?’ This approach encourages others to make connections with future outcomes, which is likely to increase their discretionary effort in achieving them. Maintaining commitment can also be strengthened by periodically measuring feelings through, for example, asking colleagues or peers how motivated they feel on a scale of 0 to 10 and what would make them motivated at a level of 10. This gives you all ideas on how to increase commitment and accelerate progress towards your goals.

What is important to bear in mind is that how you respond to your feelings can influence directly how effective you are. Say, for example, that you are angry or upset about something. If you are honest about this and identify your fears and desires, you can then ‘use’ the emotional feelings to help you feel energised and take productive action, channelling that emotion into goal achievement. Or you can let the anger cloud your judgement and bias your behaviour in ways that obstruct your effective communication as a leader.

Validating the feelings of others

It can be helpful to validate other people’s feelings. This can be as simple as asking your colleagues how they feel. By showing empathy, understanding and acceptance of other people’s feelings you are demonstrating respect for them as people and building increased trust if you do it consistently. By asking questions such as ‘How will you feel if I do this?’ or ‘How will you feel if I don’t?’ you are showing how important it is to you to take their feelings into consideration.

Being a coach

Finally, avoid giving too much advice by working in a ‘command-and-control’ style with colleagues who are competent, and criticising or judging others. In my experience of working with leaders across various industries I have found that a coaching style based on asking pertinent questions, providing support and enabling people to reflect on the consequences of their actions gives them more lasting insight into their feelings and how they can manage them more effectively in future. The key point is that being a role model for self-awareness and building quality relationships can have a positive ripple effect on those with whom you work.

2 Leading with purpose

This is linked to the discussion in Chapter 5 about the importance of making a connection between your personal and business identities because your pursuit of meaning and achieving something worthwhile with your life is an aspect of authenticity. If you are totally pragmatic and pursue opportunities without a sense of why they are important, the risk is that you show others that they are merely a means to that end. You have to make it plain in not just what you say but what you do that you are living your purpose and what you care about.

Bill George, one of the leading authorities on authentic leadership, has argued that the only valid test of a leader is their ability to bring people together to achieve sustainable results over time.2 Integral to this success has to be a genuine demonstration of your personal values that are shaped by your beliefs and developed through introspection and consultation with others over years of experience. He believes that the test of an authentic leader’s values is not what they say but how they act under pressure. If leaders aren’t true to the values they profess, trust with those they seek to lead is broken and not easily regained.

How do we recognise authentic leaders? George suggests that they typically demonstrate these five traits:

- Pursuing their purpose with passion.

- Practising solid values.

- Leading with their hearts as well as their heads.

- Establishing connected relationships.

- Demonstrating self-discipline.

To optimise your effectiveness as a leader of people, you must first discover the purpose of your leadership. To do this you need to understand the passions that make you what you are. If you have not already done this in the past, try writing down why you are a leader and what it means for you to lead others. George argues that if you are not driven by a sense of purpose and passion, then the danger is that you are at the mercy of your ego and narcissistic impulses.

This echoes our previous discussion about the power of organisational purpose. When an organisation has no clear sense of why it exists or its wider contribution to society and stakeholders other than profit (which is an outcome, after all), the risk is that its culture becomes driven by short-term motives of greed and self-interest. This, in turn, leads to a level of amorality that we have seen in banking as well as other industries in recent years, and a breakdown in the relationship of trust between the organisation and its wider group of stakeholders and society.

The importance of ‘how’

‘Big businesses are good at articulating “the what” that they’re trying to achieve, whether that’s a financial or customer target, but they often forget “the how” you achieve those targets, which is more important and where values play a big part.’

Mark Stevens, Managing Director, CCD, Provident Financial Group plc

3 Think about how you come across to others

Eric Berne was one of the first to analyse the relationships and interactions between leaders and groups in his book Games People Play.3 He developed a theoretical framework of ego states based on parent, adult and child styles and responses to describe the nature of transactions in a way that practitioners can understand and use.

The emphasis in Berne’s adult state on balanced processing of information and open, transparent transactions between leaders and followers is reflected in later work on authentic leadership. This became an important aspect of the theoretical framework I used in my research. His theories have been used extensively in improving relationships between people, groups and the organisation as a whole.

Each of Berne’s ego states (parent, child and adult) is played out in what we say and do. Recognising ego states in the behaviour of yourself and others is a valuable tool to help you build more authentic relationships with others, improve your understanding of the dynamics in many interactions and enable you to respond appropriately in a way that takes account of both your needs and those of others. Similarly, adaptive leadership emphasises the importance of effective diagnosis before action.4

The parent state consists of a set of recordings in an individual’s mind of imposed, unquestioned and external events. We derive most of them from our parents and parental figures such as teachers or mentors through experience and observation of their behaviour and speech, including encouragement and loving care as well as being told off, punishments and rules. Berne suggests that these recordings are permanent and cannot be erased. They are gathered throughout our lives and will be played back at intervals and influence our behaviour, although the degree of influence varies from individual to individual.

When adults are behaving under the influence of the parent state they can appear to be judgemental, traditional, regulatory and conventional, as well as being supportive and nurturing. They are replaying the tapes from their past. Signals that someone is acting as the ‘parent’ include verbal expressions such as ‘always’, ‘never’, ‘how many times (have I told you?)’, ‘don’t you agree that . . . ’, ‘well done’, ‘if I were you’ and ‘you should . . . ’.

Non-verbal indications of the parent state can include such behaviour as a furrowed brow, pursed lips, a pointing index finger, shaking your head and folding your arms over your chest as well as more ‘nurturing’ acts such as patting someone on the back or putting an arm around their shoulders.

The child state consists of recordings of internal events (feelings) experienced in response to external events. For example, a small child who is reprimanded by their mother may feel angry, hurt and confused, especially in the common case where they do not understand why what they did was ‘wrong’.

Like the parental recordings, those in the child state are permanent and can easily be triggered by events in adult life so as to influence our behaviour. The influence of the child on the adult’s behaviour is often to make them creative, experimental, emotional, divergent, insecure and pleasure seeking. Words that indicate someone you are talking to is acting in the child state include ‘I wish’, ‘I want’, ‘I wonder’, ‘I don’t know’, ‘I don’t care’, ‘best’ or ‘biggest’. Physical signs to look out for include a quivering lip, laughter/giggling, rapid and changeable movement, shrugging of shoulders, or a whining tone of voice.

The adult is the last ego state to develop, according to Berne. It begins only after the infant is ten months old and consists of data acquired and computed through exploring, thinking out and testing ideas. The adult state seeks for information, respects other people, estimates, and is constructive and non-dogmatic. It uses the data stored in the parent and the child states as information inputs alongside what is discovered by physical and social exploration of the world. It examines and tests the data, updating and amending it to make it fit other knowledge.

When someone is behaving in an adult state they will typically be reasonable and act with a problem-solving approach. They will have a body posture that is appropriate to their being in the moment and will generally appear calm and confident. They will ask questions such as ‘why?’, ‘what?’, ‘where?’, ‘when?’, ‘who?’ and ‘how?’, while ways of talking might include ‘I see’, ‘I think’, ‘probably’, ‘possible’ and ‘relatively’.

We need to bear in mind that each of these ego states can be helpful in different circumstances. The child in its creative, uninhibited form can be valuable in a brainstorming session, for example. Rules of thumb derived from the parent can be a useful guide to what to do in situations where the large number of questions and unknowns would otherwise lead to an impasse, helping us to make sense of ambiguous situations and to make balanced decisions based on the available information, even if it is not at the level of detail we might prefer.

Both child and parent states, however, can be highly disruptive as a leader. The child state can lead to outbursts of temper while the parent state can lead to being overly critical, rigid dogmatism and resistance to change. The only ego state that it is desirable to have functioning at all times is the adult, because this maintains awareness of the parent, the child and the situation, and determines what behaviour is appropriate to the situation. There are echoes of the emotional chimp taking over our mind in Dr Steve Peters’ The Chimp Paradox – staying in the adult state allows us to control the chimp rather than the other way around.5

Staying in the adult style is particularly important when reinforcing across the business the freedom framework of purpose, strategic direction and values – the organisational narrative that enables people to act intelligently and collectively. Too much reinforcement can come across as controlling and ‘critical parent’, which can provoke a rebellious ‘natural child’ response. Too little can lead to a laissez-faire approach where distribution of leadership is not coordinated and lacks clear parameters, which leads to inconsistency and ultimately to strategic incoherence.

4 Opening up

As we saw in the previous chapter, self-awareness means being honest with and about yourself. That is the first stage in reaching a better understanding of your relationships with different people. You will find it very difficult to create an atmosphere of trust in your relationships without such self-disclosure.

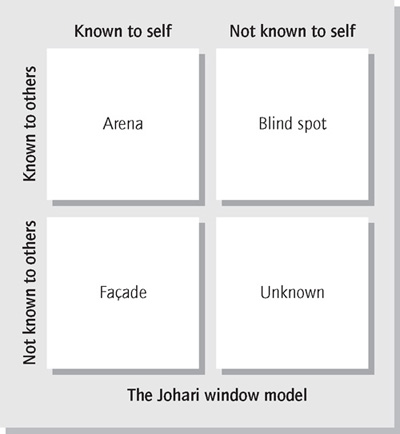

The Johari Window, developed in 1955 by two American psychologists, Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham,6 can help you identify four kinds of information about yourself that affect your communications and relationships with others, as shown in Figure 6.1.

The Johari model charts the information available to you and others in four categories, based on understanding whether each piece of information is known or unknown to you, and known or unknown to others.

- In the arena pane the size of the open pane reveals the amount of risk you take in relationships. As relationships become deeper the open pane gets bigger, reflecting your willingness to let yourself be known. It includes things you know and don’t mind admitting about yourself.

- The blind spot pane consists of all the things about yourself that other people perceive but of which you are not aware. You may, for example, think of yourself as confident and self-assured, but because of your nervous mannerisms others may see your insecurities. The more you learn about how others see you, reducing the information in your blind spot pane, the more you will be able to have open and transparent relationships with them.

- The façade pane is where you exercise more control. It comprises the information (such as history, feelings and motivations) that you prefer not to disclose to someone else. It could be concerns about others or information about yourself that you wish to conceal. The more you conceal, however, the less open and trustworthy you are likely to appear to others.

- The unknown pane is made of everything unknown to you and to others. No matter how much you grow and discover and learn about yourself to shrink the pane, it can never completely disappear. It includes all your untapped resources, all your potential, everything that currently lies dormant. Through increasing your communication with others you can, however, reduce the size of this pane, which will help you strengthen your relationships of trust with others.

The panes are interdependent. A change in the size of one of the panes will affect all others. For example, if through talking to a friend you discover something you never knew before (something that existed in the blind spot), this would enlarge the arena pane and reduce the size of the blind spot pane. Your discovery could be something insignificant or it may be something important, such as ‘Jim finds it difficult to challenge you in board meetings’.

You can draw a new window for every person you communicate with. While the size of the panes can change according to your awareness of others, of your behaviour, feelings and motivations, it will also be different for different people because your behaviour, feelings and motivations are different. Compare, for example, the types of window you would have with a work colleague and a member of your family.

It can be rewarding and satisfying to add to your arena pane, but also painful because it does involve some risk. You need to use care and discretion on occasions as an inappropriate disclosure can be damaging, whether you are giving it or receiving it. However, the more you reveal yourself to others, the more you will learn about yourself. The more truth about yourself you are willing to accept from others, the more accurate your self-concept will be.

Self-disclosure can help develop your leadership relationships. If you are finding it difficult to build a strong relationship with a key individual at work, for example, it might be useful to volunteer some more personal information about your out-of-work life than you would typically disclose with work colleagues, such as a recent experience you had when involved with your hobby. You could then ask them what they do out of work that they enjoy. You can continue using the same give-and-receive sequence with more work-related topics that might otherwise not be discussed between you. By gradually increasing the size of your arena pane with this person you will build more trust, which can lead to further sharing of information and strengthen your relationship and ability to work well together.

5 The power of feedback

A helpful way to reduce your blind spot pane and increase your understanding of the impact you have on other people is through receiving effective feedback from those people on a regular basis. Every morning I look in the mirror to help me shave and prepare for the day ahead. The reflection in the mirror (like feedback) gives me the information I need to be able to manage my own actions well (and to avoid cutting my neck with my razor).

Feedback from other people is essential if we are to be effective, self-aware leaders. Ironically, as leaders we are often in danger of receiving less than normal. The lonely leader syndrome is all too frequent in companies I have worked with over the years, with senior figures treated with too much deference and with communications filtered to make sure they are palatable. This is completely out of kilter with what is happening in the outside social media-fed world in which these companies operate, where feedback is instant and unedited. Customer complaints about large companies on Twitter can reach millions of other customers within moments. So as a leader you need to ensure you have open and unedited feedback on your impact and on your performance from across your business and from customers if you are to maintain a healthy level of self-awareness.

This feedback will help you to become more aware of what you do and how you do it. Receiving it gives you an opportunity to change and modify in order to become more effective. Feedback is best given in a supportive and balanced way, although as a leader this is not always something over which you have complete control. If you genuinely ask people in your company or your customers about how you come across, how you make them feel and/or how they think you could improve, you will sometimes get unedited responses that may be less palatable but probably very valuable.

Your challenge is to receive such feedback with good grace and to look for any lessons you can take. In addition, when you receive strong feedback it is worthwhile looking into it carefully. It may be an outlier’s view from someone with a grievance or who has personally been hurt by you or your business. It may, however, be a view from someone who had the courage to say the words that others also think but are not brave enough to articulate. A lesson I learned many years ago from Stephen Covey was to assume positive intent.7 In other words, to assume that the other person is working from noble motives and to seek to understand what is being said as insight rather than unfair criticism.

When you give feedback to others it is helpful to focus on the behaviour rather than the person, in terms of what is done rather than what we imagine their motive to be, and to avoid assumptions. For example, if you say to a colleague ‘When you shook your head I thought you looked disappointed’ rather than ‘You don’t like it, do you?’, you avoid making inferences about their views which may or may not be demonstrated by their behaviour.

Feedback can be very effective in influencing the behaviour/performance of your colleagues. If you want your colleagues to do more of something, you can confirm that by giving them clear feedback, examples of what they do that you want more of. For example, ‘Thank you, this is exactly the standard of accuracy we want.’ If, however, you want your colleagues to do something differently, you can influence them by describing clearly what you want to see. For example, ‘To reach a higher standard of quality it would be helpful if you could . . . ’ Note that being specific is always better than generalising, which risks being too vague to be of value to the other person. And avoid judgements or offering too much advice, especially when you are more senior to the other person, as this restricts their ability to reflect and learn.

When you make giving and receiving feedback frequent and normal you will have helped to create a feedback culture, where information is exchanged among consenting adults in a constructive way to fuel improvement and performance.

Balanced processing of information

Some of the less effective leaders that I meet too often work from a set of preconceptions. They have a view of what’s worked in the past and therefore what the right answer is now. Or they believe they need to have the right answer because they are ‘in charge’ and therefore they might ask people questions and gain input, but they then fit the information to a predetermined course of action.

Balanced processing of information plays an important role in maintaining an adult approach as an authentic leader. It involves suspending immediate judgement and treating your own view as one source of input and balancing it with a range of other inputs from diverse sources. This demonstrates more of an ‘adult’ approach than a ‘parental’ style, which might come out as ‘I’m right because I’m the boss’ or ‘Just do it’. Balanced processing is linked to genuinely listening to understand. It draws on your inward emotional intelligence and ability to understand what’s going on around you at this particular moment.

It encourages you to behave in the way you choose to behave rather than having an unwelcome emotional response overtake your responses and lead to unbalanced decisions and actions. Balanced processing leads to decision making that is in the best interests of the organisation and which in turn inspires confidence, which we will discuss further in Chapter 7. As you manage your own reactions and draw on balanced input from available sources, the level of commitment from others to implementing the decision will consequently be that much higher.

1 Situational awareness

In order to process information in a balanced way, you need to have a healthy level of situational awareness, which is about being aware in the present and within any situation that you’re in. It is quite often framed in terms of decision making, and it is about making those decisions in the context of your values and how you choose to react. This draws on your ability to manage your emotional responses effectively. It means taking into account other people’s views, data and circumstances, and being able to formulate a more holistic, more balanced and more comprehensive understanding of the nature of the problem and the possible solutions. It needs you to be a careful listener, to sense how others are reacting, and to process this range of data in an objective way that is free from bias.

You can practise your situational awareness by holding reviews at the end of meetings, getting input from each person on what they perceived to have been effective in the meeting and how they would improve the meeting next time. In this way you can test your own reading of the meeting, its personal interactions, dialogue, decisions and levels of commitment.

Being free from bias takes some thought. When we perceive an event or occurrence, the data we receive through our senses goes through an internal ‘filter’. This filter influences how we respond to things and people, and can be a source of unconscious bias. If I have, for example, an unconscious bias that quieter people have less to offer, in a meeting I may judge an introvert colleague who makes only occasional contributions as not being as able or as interested in the discussion as more extrovert people present. This may in turn affect how I interact with that person, and ultimately how I judge their performance and fitness for promotion. The opportunity for unfair or unfounded decisions is clearly evident, although consciously I might refute that I had such a bias in the first place.

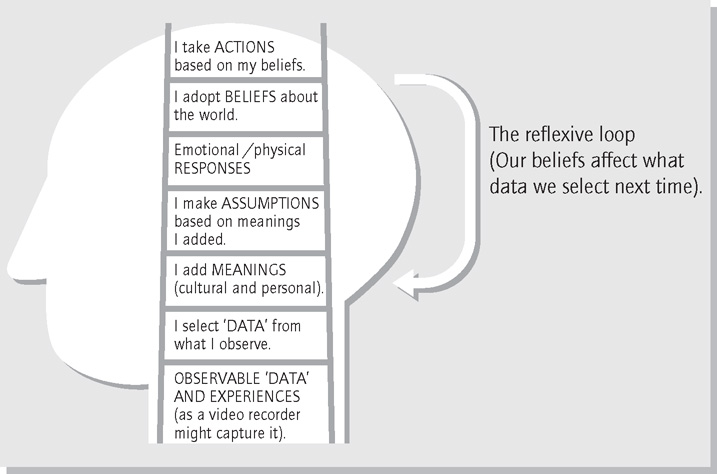

We can look at this through what is called the ‘ladder of inference’ (see Figure 6.2), which represents this internal process and helps us see how our beliefs affect how we comprehend data when we have to make a decision. The model was defined by organisational psychologist Chris Argyris in 1985, with the rungs depicting the psychological steps we go through between perceiving an event and responding to it.8 Exploring the rungs in relation to a particular event can help you bring what is unconscious to conscious awareness.

For example, imagine you send three emails to Jane but get no response. The data you select could well be ‘no response’, to which you add the meaning that Jane is ignoring you for some reason and that she is therefore being rude. You might be tempted to then assume that Jane does not like you or that she doesn’t want to do what you requested in your emails. Your emotional response could be frustration or disappointment, which causes you then to believe that Jane is not reliable. Finally, you decide not to ask her again and not to recommend her to others. All of this is justified in your mind because it is based on ‘a grain of truth’, that she did not reply to your emails.

You can adjust your inner radar and influence your resulting behaviour to help manage the ladder of inference process more consciously. For example, you can explore and understand better your personal ‘triggers’: what attributes, behaviours or cues do you particularly notice? What do you respond to positively or negatively? How does this change when you are stressed or distracted? How can you manage these responses more effectively? Think about how you position people to others, such as clients or colleagues: who do you put your social capital behind and why? What does this tell you about what you prefer and therefore what you might be biased against? Using these questions you can start to understand and therefore modify your internal bias and become more balanced in the way you process information and make appropriate decisions. This in turn will increase your authenticity and inspire more trust from others.

2 Honest conversations

Honest conversations are at the heart of open and transparent relationships. The more you can have honest and straightforward conversations with others, the more connected you will be with them. But it can take some preparation if the topic of the conversation is in some way controversial or potentially offensive. When planning such a conversation it is helpful to decide what you want to achieve in advance and to put yourself in your colleague’s shoes to see the conversation from their perspective.

During the conversation listen attentively (with eyes as well as ears), acknowledge any strong feelings you or they may have, and genuinely explore alternative points of view (your assumptions might not be correct). This is a time to draw on your emotional intelligence and to avoid getting hijacked by your emotions. Instead, remain calm and avoid judgemental or emotive language. Finally, if it is appropriate to suggest improvements, do so with respect and stay in an ‘adult’ state (avoiding a ‘critical parent’ tone of voice). It can take some courage to confront awkward or sensitive conversations, but if you do so with a careful and open approach it can build stronger, more trusting relationships.

One technique that can be helpful in discussing problematic situations is to frame them as problems you and the other person or people need to solve. If you ask questions to invite your colleague to explore the causes of poor performance or the reasons why they might appear not to be fulfilling their potential, you are indicating that you are keen to resolve the issue collaboratively. Having a two-way conversation about problems or barriers to high performance and their possible solutions engages the other person and gives them more of a feeling of ownership of both the problem and the solution. It’s important to try to identify whether the cause is poor ability or poor motivation. If they can’t identify a solution, you may have to – but the key thing to keep in mind is that it’s not always up to you.

3 Managing conflict

Despite our best efforts we can find ourselves facing a situation that feels like ‘you against me’. Here are four ways to help you get back to ‘us against the problem’.

- Focus on the other person, accepting that they have opinions, feelings and intentions. As described in the last chapter, empathy provides a basic human bridge which can give you a route for developing more constructive discussions and outcomes between you and them.

- Look behind what they say they want in order to try to understand what they need. If you can satisfy both their needs and your own you are more likely to achieve a mutually beneficial outcome.

- Invite solutions as well as sharing your own. In conflict situations it is natural for people to take positions, which can easily become entrenched. By inviting ideas from the other party you are reducing their feeling of isolation and encouraging a reduction of the entrenched positions towards a more shared view of the situation.

- Build on ideas and suggestions to reach a win/win situation. If the other person is involved in defining the solution they are more likely to be committed to its execution, as well as feeling more positive about the conversation itself.

Looking for a mutually satisfying solution can be a disarming approach and one that can reduce tensions and encourage a more connected discussion: ‘My view is that . . . what’s yours?’ The sense that we are in conflict often hides the fact that we are actually trying to achieve similar things; try asking ‘What would a good outcome look like for you?’ Seeking to change someone’s view implies they are wrong, while seeking to understand the situation suggests they are okay. This is a way of thinking that increases collaboration and mutual problem solving.

Strengthening key relationships – questions to ask

As we have seen throughout this book so far, the connected leader uses influence to create the right mindset throughout the organisation. In order to use that influence wisely and effectively, however, it’s important to map the key relationships you have to identify areas of strength and those needing improvement. I would encourage you, if you have not already done so, to list the key relationships you have at work. Who are the people or stakeholder groups with whom right now it is most important to have strong, connected relationships? For each relationship use the techniques in this chapter to consider the current status of the relationship and how you might improve the quality of the connection, such as:

- Do you demonstrate high-quality emotional intelligence in how you interact or could this improve? Do you understand what motivates them and how to make sure they get what they need from your relationship?

- Is it mostly an adult-to-adult relationship or does it need to shift to be so?

- Are you working with the same quality of information?

- Do you process information together in a balanced way or do you tend to make decisions based on your judgement alone?

- Do you both operate in the arena pane or could you be more open with each other?

- Do you share a robust level of feedback or could you strengthen the level of feedback in either or both directions?

- How honest with each other are you?

- If there is conflict, how can you engage with them to find a mutually beneficial solution?

For each relationship on your list, decide on the area for improvement that will have most benefit from your analysis using the questions above. I would now encourage you to discuss it with them in person, so that you can together explore whether they see the opportunity for improvement in the same way and how they think you could improve. Between you, agree a course of action that will achieve a rapid and significant improvement in the quality of connection and put it into practice.

Agree to review progress after, say, a month and meet then to discuss what has improved, what you can learn and how you can proceed further. It can be very helpful to have regular conversations with your colleagues and wider stakeholders about how to strengthen your relationships. Having a clear focus for such conversations gives them legitimacy in both parties’ minds in what might otherwise be very task-oriented meetings.

Connected leader’s checklist

- Having open and transparent relationships with people, including customers, colleagues and other stakeholders, is a key requirement to become a connected leader

- If you can process information in a balanced way you will inspire confidence in others and make better decisions

- Seek feedback whenever you can to learn and to provide a role model for others.

Notes

1 Towers Watson (2008) ‘Global Workforce Study 2007–2008: Closing the engagement gap: a road map for driving superior business performance’, London: Towers Watson.

2 George, B. (2003) Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the secrets to creating lasting value, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

3 Berne, E. (1964) Games People Play: The psychology of relationships, New York: Grove Press.

4 Heifetz, R., Grashow, A. and Lensky, M. (2009) The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press.

5 Peters, S. (2012) The Chimp Paradox: The acclaimed mind management programme to help you achieve success, confidence and happiness, London: Vermilion.

6 Luft, J. and Ingham, H. (1955) ‘The Johari window, a graphic model of interpersonal awareness’, Proceedings of the Western Training Laboratory in Group Development, Los Angeles, CA: UCLA.

7 Covey, S. (1989) The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, New York: Free Press.

8 Argyris, C. (1985) Strategy, Change and Defensive Routines, Southport: Pitman.