Chapter 9

Creating an agile organisation

Making their organisations ‘agile’ has become one of the top priorities for today’s leaders. But there is a big gap between the desire and the implementation, since it demands a delicate balance between embedding the sort of organisational flexibility that is nimble and responsive to customers and competitors, while at the same time holding true to a clear purpose and direction.

This chapter discusses how you can begin to deal with modern turbulence by:

- innovating by unleashing the entrepreneurial spirit in your colleagues

- developing a learning organisation

- becoming an adaptive leader

- prioritising ruthlessly.

Dealing with turbulence

Today’s C-suite leaders are well aware that agility is critical to deal with what we are calling the VUCA world, or one characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity.1 They appreciate the importance of equipping their organisations to survive in an environment characterised by increasing demands from customers and the increasing challenges from competitors and new technologies.

The predictability of the ‘old’ world really has disappeared for most organisations. In the last 20 years we have experienced two or three deep recessions, major disruptions in the business–customer relationship, the pervasiveness of social media, the demand for more transparency and accountability, and increasingly disruptive technologies.

Most organisations are now working in the context of globalisation and international interdependency, either directly or through their customers. This creates a high level of uncertainty and the need to be nimble, neither of which is compatible with the command-and-control style of leadership, with its over-emphasis on centralised policy and weak support for individual initiative. As noted earlier, complex adaptive systems learn how to survive and flourish in these unpredictable environments. Adaptive leadership provides a helpful synthesis of change leadership thinking for this new reality.2 It is about changing the whole system, through effective diagnosis and action, as opposed to technical change within the system (which typically is less successful). Adaptive change emphasises innovation and learning, as well as persistence and seeing and overcoming obstacles as the system tends back towards homeostasis. Heifetz et al. talk about ‘the productive zone of disequilibrium’, which is like a pressure cooker to get the change to stick, which echoes the disruption going on in the world of technology. Later on in this chapter the use of disruptive leadership development is discussed as a way to help leaders develop a more adaptive approach to change. If you remember the exponential rate of technological progress from Chapter 2, you can start to appreciate the extent to which we need a new leadership approach.

Disruptive technologies

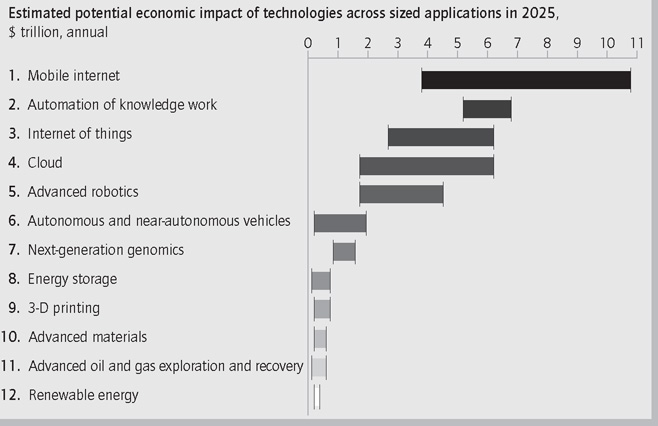

In 2013 the McKinsey Global Institute published a report which identified 12 technologies that could drive truly massive economic transformations and disruptions in the coming years.3 It estimated that, together, applications of the 12 technologies discussed in the report could have a potential economic impact of between $14 trillion and $33 trillion a year by 2025 (see Figure 9.1). According to McKinsey, this estimate is neither predictive nor comprehensive. It is based on an in-depth analysis of key potential applications and the value they could create in a number of ways, including the consumer surplus that arises from better products, lower prices, a cleaner environment and better health.

As Siemieniuch and Sinclair have remarked, ‘in 30 years’ time we will be designing and servicing products we can’t yet define, for uses that will change, perhaps abruptly, utilising materials not yet invented, in processes we have not yet developed, using suppliers who will become very different to now, and we will be doing all this with people who do not yet work for us, utilising profits we still have to earn’.4

The Oxford English Dictionary defines being agile as ‘able to move quickly and easily’.5 Organisational agility thus presents something of a paradox. You have to be able to identify and respond quickly to emerging threats and challenges while at the same time having a firm vision of your strategic plans and coordinated activity to execute them. This paradox is at the heart of connected leadership, with its stable foundations and flexible and evolving ways of working.

Creating an organisation that is ‘able to move quickly and easily’ needs a strong spine and supple muscles. Embedding organisational flexibility has to be based on a strong spine of clear purpose and direction and a strong sense of shared values, with the flexible muscles of colleagues who are empowered to take decisions based on their proximity to customers and a willingness to trust and collaborate. The final component in this flexible anatomy is the innate ability to learn, to improve, to share knowledge and to be disruptively innovative. This is the final factor in the connected leadership model and it unlocks the rest of the model by providing the lifeblood of agility: learning.

The key for a more connected type of leadership is that it is ‘networked’, in that the people in your organisation have the shared intelligence to be able to respond to local priorities while maintaining the collective cohesion – just as a successful soccer or rugby team shares a collective intelligence that allows highly fluid movement without losing its tactical shape. Each player knows what they are seeking to achieve collectively, so is therefore able to exercise judgement about being in the right place at the right time to maintain interdependence in the face of determined competition.

Through learning, innovation, continuous improvement and managing ambiguity you can enable your business to adapt quickly and respond to local customer needs within the parameters set by your purpose, direction and values. As one CEO said to me, although the need for agility is fuelled in a large part by technology, success is really about changing the way people work, the way they think, the way they view data and the way they interact with customers.

Innovation: unleashing the entrepreneurial spirit

One of the big challenges for many of the companies we work with is to encourage a more entrepreneurial, responsive and risk-taking mindset among all their colleagues – a challenge when they number in the tens or even hundreds of thousands. In a small start-up it is relatively easy to build and maintain a culture of innovation, with a shared sense of doing something exciting and pioneering. In larger and more established companies this is a bigger challenge.

In an innovation culture the customer often looms large in the organisation, with every effort focused on anticipating and meeting what current and future customers need and want. The culture is fast, flexible and adaptable and people naturally respond in this way in the best interests of the business and the customer. This drives breakthrough thinking to create real innovation in processes, products and services, with the determination to follow through to actual market release and commercial success. Typically, people are highly capable, keen to work as a team and enable others to conceive and articulate innovation and see it through to it actually hitting the market. These people are inquisitive, seeking constant improvements and never satisfied with ‘good enough’. Everyone is encouraged to seek repeated improvements to the ultimate benefit of customers. In some companies there is a competitive culture, externally and sometimes internally, to get the best possible results from great ideas and to get there first. As well as being agile there is a real discipline about execution in order to commercialise ideas brilliantly and to build quality into every part of the process.

One large company I know put into place processes that encourage people to ‘fail fast and learn’, or, in other words, to experiment by starting small, testing and, if it fails, to learn from it and apply that learning in the next iteration or project. An important element in doing this is not to over-burden these experiments with too many rules. Rapid application development and prototyping are related ways to build more agility and take risks but in a contained way, keeping any potential risks smaller and more manageable.

What is essential is to develop a sustainable, repeatable and methodological process of drawing out creativity and innovation, rigorous analysis of ideas, a route to the development of those with most promise and making them happen. Crucially, innovation is rarely successful in isolation. It flourishes where there are both formal and informal meetings with a wide assortment of people both internally and externally who can exchange ideas and learning. This sharing of best practice is pivotal to success. Bringing people together into cross-functional teams to think about the same problem from different perspectives can lead to significant and innovative solutions to problems. It also helps to break down functional silo mentalities (where colleagues look inward and focus on protecting their turf rather than seeking breakthrough ideas).

The National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools suggests the following framework to shape an innovative culture:6

- Look for successes. Assign a best practices team or coordinator to take charge of this process to establish routine procedures to look for internal successes. For example, an ‘after-action’ review is a helpful and structured debrief of what happened during an event or project to learn from the experience.

- Identify and validate best practices. Identify which practices account for the success of top-performing areas. For example, determine whether environmental or personal factors, or internal practices, account for a unit’s success. Using internal benchmarking to compare the performance of different units in an organisation may be useful, especially when they perform similar activities.

- Document best practices. Write a description of the best practice and maintain a central repository. Direct people to the developers of a practice and to related communities of practice so they can learn from other people’s hands-on experiences. At Mandarin Oriental Hotels, for example, there is a shared database of best practices that each hotel can contribute to and draw from, encouraging sharing across locations.

- Create a strategic plan to share best practices. Design and carry out a strategic plan to share knowledge about internal best practice with the potential users who can most benefit from it. This includes identifying and recruiting the support of people who can help create demand for the development of a best practice and promoting on-the-job learning. Communities of practice bring together people with a shared professional interest (such as software engineers or quality technicians) to exchange insights and experiences, as Xerox did with its photocopier engineers.

- Adapt and apply best practices. This last step is to help people apply best practices in their own settings, which may be different than in the place where the practice was first developed. For example, guidelines could be developed on how to adapt a best practice to different settings or functional areas. At Three, the mobile phone network, ideas developed in the team that runs the network need to be revised to be useful in the multi-channel retail side.

Celebrating learning

This approach to innovation is summed up in the now-famous quote by Reid Hoffman, the founder of the successful social networking site LinkedIn: ‘We don’t celebrate failure in Silicon Valley, we celebrate learning.’7

Naeem Zafar, academic, writer and entrepreneur, in a series of articles in The Atlantic magazine which looked at just what made Silicon Valley such a thriving centre of innovation, described five main ways these entrepreneurs succeed in translating innovation into actual businesses:8

- They encourage a culture of collaboration both formally and, perhaps more importantly, informally.

- They align both social and economic incentives so that everyone is committed to building something amazing.

- They assemble a critical mass of talent of highly educated, highly motivated people.

- They have respect for intellectual property.

- They have capacity to celebrate failure since those who failed have learned invaluable lessons about what not to do.

It is interesting to reflect on these for your business and to identify ways in which you can push further with at least one of these characteristics in order to strengthen the innovative gene in your organisation.

Develop a learning organisation

Much innovation stems from having a learning culture in place where people share knowledge and ideas as a matter of course. Your role as leader needs to include encouraging learning and improvement across the whole business. Ask yourself:

- Is information shared and easily accessible to everyone?

- Is learning an ongoing, never-ending process?

- Are people inspired and motivated to learn and is tangible value placed on it?

- Are people encouraged to make mistakes?

Learning is becoming a pervasive and central part of our knowledge economy. Millennials do not see a distinction between learning at work and personal learning, as it is all enabled by the internet and the proliferation of information we have at our fingertips. In the networked society we can all be learning all of the time and if you can harness that innate human curiosity in your business you will have captured a wave of energy and ideas that can really drive innovation and improvement.

It was not long ago that personal devices were not allowed onto the corporate networks of many organisations and all managers were issued with a BlackBerry device for email and telephone use. We are now in a device-neutral world where personal and work communications are via the same smartphone and for most of us now effectively integrated. This creates opportunities for you to fuel the learning equity of your business by encouraging colleagues to learn constantly and to bring it to bear at work. Offer prizes for the best innovation of the week, or of the day, and celebrate examples where people have ‘Googled’ something and found a new way of doing or thinking about a process or a product.

In today’s economy, according to Krebs: ‘All individuals, communities, systems, and other business assets are massively interconnected in an evolving economic ecosystem. In the connected economy, each network actor (individual, team, or organisation) is embedded in a larger economic web that affects each participant and, in return, is influenced by that participant. In such a connected system we can no longer focus on the performance of individual actors – we must manage connected assets.’9

The formation of such communities allows high levels of learning to become the norm. Often smaller organisations are more naturally attuned to this approach because they are much closer to their customers and the market. Larger ones have the problems of their sheer scale and their need for elaborate structures which enable them to function. Those structures and processes, however, can mitigate against flexibility, learning and adaptation when they become bureaucratically complex, which slows things down. In one client I witnessed small teams forming to share technology research across product categories as a result of managers participating in a leadership development programme. One of the teams combined customer insight from a retail manager with product innovations from two category managers and the resulting chocolate underpants for Valentine’s Day were a great commercial success. This type of result can help to spark more cross-functional innovation if you help to relate the story across the business.

The concept of the learning organisation first emerged in its present form through work by Peter Senge and others into how organisations had to become more interconnected and hence agile enough to deal with market changes and upheavals. Senge, professor at MIT and founder of the Society for Organizational Learning, has created a blueprint for the learning organisation10 consisting of five main elements:11

- Personal mastery. This involves formulating a coherent picture of the results people most desire to gain as individuals (the personal vision), alongside a realistic assessment of the current state of their lives today (the current reality). This is linked to the importance of building individual confidence and capability in order to enable empowerment.

- Mental models. This looks at the importance of developing awareness of the attitudes and perceptions that influence thought and interaction. By continually reflecting upon, talking about and reconsidering these internal pictures of the world, people can gain more capability in governing their actions and decisions. Authentic leadership relates to this through the lens of shared values and assumptions.

- Shared vision. People learn to nourish a sense of commitment in a group or organisation by developing shared images of the future they seek to create and the principles and guiding practices by which they hope to get there. This is a key part of purpose and direction.

- Team learning. Through techniques such as dialogue and skilful discussion, teams transform their collective thinking, learning to mobilise their energies and ability greater than the sum of individual members’ talents, fuelling collaborative achievement.

- Systems thinking. People learn to better understand interdependency and change and thereby to deal more effectively with the forces that shape the consequences of our actions. Systems thinking is based upon a growing body of theory about the behaviour of feedback and complexity – the innate tendencies of a system that lead to growth or stability over time (this relates to complexity leadership theory and in particular to the adaptive and enabling functions of leadership).

You will have noticed the links between these elements and the five factors of connected leadership. We are still some distance from realising the ideal of the learning organisation, argue some observers, including David Garvin and his co-authors, who suggest three main reasons for this.12 First, discussions too often say less about how this is to be done and more about why. Second, the concepts are aimed at leaders and senior executives rather than at lower-level managers who have little idea how to put it into practice. Third, there are too few standards and tools. They believe that there are three key building blocks to creating a successful learning organisation:

- A supportive learning environment. This is one where colleagues feel safe to own up to failure and try again, where opposing and competing ideas are welcomed, where there is openness to new ideas and, notably, time for reflection.

- Learning processes and practices. This is an important step and one that is too often missing. It involves designing and implementing learning processes which contribute to the systematic generation, collection, interpretation and dissemination of information.

- Reinforcing leadership behaviour. If a leader actively questions and listens to colleagues in a supportive way, people will feel encouraged to learn. Garvin quotes the former chief executive of American Express, Harvey Golub, who wanted to encourage really open-minded discussion by making it plain that he was ‘far less interested in people having the right answer than in their thinking about issues the right way. What criteria do they use? Why do they think the way they do? What alternatives have they considered? What premises do they have? What rocks are they standing on?’

Taking part in learning activities yourself can make you a more effective role model for learning, according to Milway and Saxton.13 This is as much about culture and your behaviour as leader (and how that helps to create the culture) as it is about processes and systems to support learning, sharing and effective innovation. The processes and systems need to be in place but they won’t really work well unless the culture supports that type of activity. In some clients with whom we work, the CEO and the board embrace the opportunity to attend leadership programmes or coaching sessions or assessment processes. In these clients the role model provided by the board sets an example for others who therefore take the learning opportunity more seriously. In other clients it is more difficult to get full participation from senior leaders and the resulting cynicism from other leaders gets in the way of their learning.

You have to encourage a climate of learning, taking risks, learning again and doing something different. From senior leaders stepping back and encouraging others to take decisions through to local leaders encouraging learning and adaptation, the behaviours are about enabling the organisation to operate on the basis of accepting mutual influence, respecting others and making careful decisions that balance the organisation’s and the customer’s needs.

Admittedly, it can be hard for a leader to let go of control and adopt a more coaching style of leadership. But what it signals is that people are being allowed to ‘get on with it’, something very important for an agile organisation that needs space to innovate, fail and try again. You can be highly effective by supporting, coaching and providing space for others to learn, just as architects create space for living through focusing on the space between things.

Milway and Saxton also recommend creating a culture that values continuous improvements through aligned beliefs and values, reinforcing incentives and commitment to measurement of results. This link between having a culture that encourages learning and seeing continuous improvement is echoed by David Brailsford’s emphasis on marginal gains in the way he coached British cycling to achieve seven gold medals at the 2012 Olympics and helped Team Sky to win two Tour de France titles in successive years in 2012 and 2013.14 Brailsford and his team applied learning to every aspect of the team’s performance, from obvious areas such as bike design and rider fitness, to sleeping patterns and diet. Examples of what they learned and implemented included taking along riders’ own mattresses and pillows to prevent neck and back problems and even training the team on how to wash their hands correctly to reduce the chance of infections. This approach epitomises how learning drives improvement, which drives performance.

Disruption builds adaptive leaders

Reviewing recent leadership research and looking at what works in practice confirms that in today’s uncertain and unpredictable environments leaders need to be less rigid and centralised. Fletcher, for example, has described three characteristics of this style of more distributed leadership:15 1) leadership as practice, so it is based primarily on what you do rather than what you say; 2) leadership as a social process, where your influence is through how you interact with the people around you and across your business; and 3) leadership as learning.

Taking the last of these, we can see there is a direct link with the adaptive function in complexity leadership theory (see Chapter 1) which is partly of value to an organisation because it provides learning ability closer to the customer interface and facilitates sharing of knowledge across the organisation.

Stacey has argued that the benefit of uncertain environments is that organisations are almost forced to respond by embracing constant change and adaptive behaviour.16 This tends to increase agility and the ability to respond to changing local market or customer requirements quickly, increasing customer satisfaction and loyalty: ‘Individuals engaged in networked interactions generate innovative solutions’,17 which relates to the collaborative achievement in the previous chapter.

I have found that creating highly disruptive experiences as learning opportunities for leaders and others is very useful in disturbing equilibrium and enabling them to re-evaluate their assumptions about how to be successful. By taking leaders or teams of people into challenging and uncomfortable situations they are less able to rely on learned routines and behaviours to survive and prosper. They are given the opportunity to try out new ways to influence others, new approaches to team working, and even to reconsider their own view of themselves. We call this learning to feel comfortable to feel uncomfortable. This disruption of normality creates the opportunity for breakthroughs in mindset and associated behaviour.

It’s a challenging journey

‘Disruptive learning is helping us to create a new mindset among our leaders and managers, which in turn is leading to new ways of working. It is an exciting, if sometimes challenging, journey.’

Tanith Dodge, HR Director, Marks and Spencer plc

With one client we took the senior leadership cadre into disadvantaged areas of society in order to help them rethink their mental model about what leadership means. By seeking to lead people over whom they had no authority and with whom they had little in common, the leaders had to reinvent their ability to influence and collaborate with others, bringing refreshingly simple and effective methods to bear. Other examples include taking top executives into the less salubrious areas of the supply chain to work with employees, taking leaders into digital start-ups to learn about digital mindset, and taking leaders to markets in developing countries to see their products being used in local markets. The consistent element is finding disruptive experiences that provoke a challenge to your shared mindset.

Equally important to having a disruptive learning experience is being in an intense environment back at work to put it into practice. Typically, leadership development programmes finish and normal work resumes, almost as though nothing has happened. The temptation for leaders is also to return to normal. There is great value therefore in creating short-term high expectations of improvement in key business areas as a result of the programme, with associated measurement, coaching and action learning support. Expect nothing and you will probably get it; expect results and you are more likely to see them in practice.

Prioritise ruthlessly

Many of the organisations I visit are working hard to simplify their ways of working as a key way to increase agility and their ability to adapt to changing circumstances. The greater the complexity outside your business, the simpler it needs to be inside in order for you to manage your way through this environment effectively. Ruthless prioritisation is a good way to start this process of simplification. It creates clarity for yourself and others on what to focus on and, perhaps more importantly, what not to focus on, in order to enable action in times of complexity and uncertainty. Set clear priorities for the business and for your leadership team, so that everyone can then focus on doing fewer things better.

Where can you start? How about by waging war on bureaucracy and inviting your colleagues to reduce processes and paperwork to the minimum needed to serve the customer and maintain regulatory compliance? If your colleagues are empowered to be the best they can be for the sake of customers, and they are clear about a) the priorities and b) the need to strip complexity out of their ways of working, you can trust them to make the right decisions in the interest of the wider organisation.

As a leader, you also need to have the courage to slash through any bureaucratic thinking or activities which could slow down innovation and learning. We see many companies trying to simplify by eliminating procedures, rules and regulations which have grown exponentially (and often without a clear understanding of why) but which are no longer applicable to innovative outcomes. Getting rid of them can remove systemic roadblocks and wasteful use of resources. This isn’t easy given the likely vested interests involved. For you to rip up the rulebook and say, for example, we are going to slash the number of key performance indicators from 400 to 40 is brave, bold and needs careful communication. Without such symbolic acts, however, you are less likely to see real progress and reduced bureaucracy.

At the same time you should not tolerate those who stay in their comfort zones by clinging to old ways of working and thinking. Tell stories about people who have been bold in sticking to the priorities, improving processes, reducing bureaucracy and speeding up the way the business operates. But also you need to confront those who won’t participate and encourage them to get on board or to find an environment better suited to their preferences.

Going back to the head coach of the British cycling team, David Brailsford, consider the now-famous principles he followed to transform the team into one of the most successful in the UK’s cycling history.18 They offer us guidelines for how to achieve this disciplined focus.

- Ensure clarity. Be clear about purpose and responsibility, so everyone is clear about the part they play in achieving the team’s purpose.

- Create a ‘podium programme’. Aim to be the best or nothing, focus on being brilliant at a few things.

- Plan backwards. Identify your goal and then prioritise what you need to do to win, working backwards through every detail.

- Focus on process. It’s about making improvements in even the smallest things.

- Get back to basics. Be single-minded and keep everyone focused on the goal.

- Practise winning. Get small wins before big ones so that you develop the winning habit.

- Aggregate marginal gains. Focus on improving performance by 1 per cent in many areas.

- Maximise the latest technologies. Find the technological innovations that are most helpful in boosting performance in line with your goal.

Brailsford epitomises ruthless prioritisation and his single-mindedness was contagious, spreading throughout the team and driving unparalleled success. We can learn from him. If you want more agility in your organisation you need to create the momentum for change (through increased innovation and learning) as well as removing the barriers to it (such as complexity and bureaucracy). If you fail to address the latter, the former will fail, as I have seen in various organisations which have struggled to embrace the digital revolution and create agile ways of working.

As I have stated throughout this book, the things that need to remain constant are your purpose, direction and values, all in the context of creating a customer-driven organisation. In my experience, the companies that struggle to change share a tolerance of poor behaviour and an acceptance of a conservative mindset that protects the status quo. When Dave Lewis took over at struggling UK retailer Tesco in 2014 he confronted both areas quickly and decisively, removing executives who embodied unacceptable attitudes or behaviours and making structural changes such as closing unprofitable stores and selling non-core businesses within six months.

Contrast this with other UK retailers struggling to respond to discount retailers and digital competitors. They have taken years to implement changes that have not delivered expected results because they have failed to change the behaviours and conservatism that are still too present in the organisation. We only have to look at the fate of companies that were market leaders in mobiles like RIM (Blackberry) and Nokia to appreciate how quickly fortunes can change when companies are slow to respond to changing circumstances. Similarly, Eastman Kodak invented the digital camera in the 1990s but refused to exploit it in order to protect its existing business in film and processing. The business eventually failed, but it could have been very different.

case study

Agility and customer focus at Three

When Three, the UK’s fastest growing mobile operator, found itself competing on price rather than customer service, it saw an opportunity to challenge the mobile phone industry for the better and reinvent the rules. As a result, Three went from being the most complained about mobile operator to the least complained about. How did it achieve such a successful transformation?

Dave Dyson, CEO of Three, sets the scene: ‘Three only exists because a lack of competitiveness and innovation within the mobile industry led the British government to allow the introduction of a new operator back in 2003. Although the company had been created to deliver on a clear purpose, that didn’t translate into day-to-day activities, causing innovation and profitability to suffer.’

To achieve growth, Three priced its services at a discount and quickly developed a reputation for being the cheapest in the market. ‘The company simply didn’t have enough quality in its customer experience to justify charging a premium,’ says Dave. ‘It was performing at a loss and significantly undershooting expectations.’

Renewing the strategic vision

Appointed CEO in 2011, Dave’s first priority was to reconnect the brand with its purpose to make mobile better. ‘We had to get back to challenging the rules of mobile, such as the unspoken rule that if you go abroad, roaming rates are so high you have to turn your phone off. We wanted our customers to be able to enjoy using their phone overseas the same way they do at home. But to reinvent the rules of mobile and live up to our brand promise, it wasn’t enough to have great ideas. We also needed the agility to bring them to market first.’

This reinvention around the core purpose of making mobile better required buy-in from across the organisation. Graham Baxter, Chief Operating Officer at Three, adds that ‘having a shared direction and purpose is very important to Three. There is a “one team” mentality’.

Although Three has never been a particularly hierarchical or bureaucratic organisation, leaders recognised that transformation required an increasingly connected style of leadership across the business. ‘We had to develop leaders to be creative and bold,’ says Dave.

Three wanted to encourage innovation and increased agility in a supportive environment. Senior leaders advocate the ‘fail fast, learn fast and innovate’ concept. ‘I believe in acting your way into a new way of thinking rather than thinking your way into a new way of acting,’ says Graham. ‘Otherwise you never actually act. So let’s just start with something and then make it better.’

Leaders at Three believe that successful customer engagement starts with highly engaged colleagues who connect to the organisation’s purpose and values. ‘In order to have great conversations with our customers, we have to have great employees,’ says Graham. ‘We wanted to improve employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction and cost control. Some people say you can’t have all three. But if you get that shared purpose right then you can.’

Starting from the top

In order to connect people to purpose and develop more agile and customer-focused behaviours, Three introduced a major programme of leadership development. ‘Making the transition from being price-led to brand-led was a huge strategic shift,’ explains Lesley Davies, Director of People Experience at Three. ‘We couldn’t just flick a switch, so we introduced learning and development that would drive the change for our senior leaders, including the board. We began by helping the board to clarify its vision and explored the pockets of excellence already in place when we saw great customer centricity in action. We identified six competencies to drive agility: customer-centered, business-savvy, explore, collaborate, engage and deliver.’

The modular leadership development programme, supported by coaching and a specially designed leadership app, focused on increasing self-awareness and helping leaders to understand the impact that they had through their habits and preferences. Leaders also explored their impact on the team and the business, helping them to see which styles helped to increase pace and agility.

Gathering data on the preferences of the top 50 leaders unearthed valuable insights. ‘A key learning point was that the predominant working style was to “be perfect”, making leaders want to acquire more information and data than they actually needed to make decisions,’ explains Lesley.

The eight board directors were the first to go through the programme, which helped to position them as role models. ‘The learning made you feel physically uncomfortable, it was so impactful,’ says Dave. ‘Unlike reading a book, the use of actors and real-life business scenarios forced you out of your comfort zone onto a steep learning curve. Everyone took away something different. For me, this was speed of decision making.’

Profiting from being more agile

Graham believes that people across the organisation are now more adept at mobilising swiftly towards achieving a goal. ‘We can adapt and move quickly. We are increasingly responsive, which both suppliers and customers appreciate.’ Lesley adds that ‘investing in leaders and adapting our leadership style has helped make our customers love us’.

Three believes that in a fast-moving marketplace, a clear direction is critical to its success. ‘Keep the strategy simple,’ advocates Graham. ‘We can’t do everything. Resources are limited, so we focus on a small number of priorities. We don’t get distracted by all the things we “could” do. We focus on what we “can” do, and do well. We are very tuned in to our customers, and prioritise the things that benefit them most. Complexity can create confusion. It dilutes your message. Focus leads to clear business outcomes.’ As recognition of this, Three won Best In-Store Customer Experience (Mobile Choice Awards) in 2014.

Leaders at Three genuinely see people as their greatest asset and believe it is impossible to deliver a great customer experience without investing in people to develop skills and behaviours in line with a shared purpose and direction.

‘Engaging people gives them the confidence to execute strategy,’ says Graham. ‘Our performance improves every month because people get it. Whether working in our customer contact centres or in our stores, people get it. And rather than reward individual effort, we want to reward shared outcomes. We want to encourage team thinking and rally people around a shared purpose.’

By galvanising people around its shared purpose of making mobile better and responding to customer needs with agility, Three has seen results improve. ‘Developing more connected leadership has had a lasting impact,’ says Dave. ‘People in the business feel confident that they’re working on the right things. We have increased speed of decision making and are performing better as an organisation. Everyone is aligned to and excited by our core purpose, increasing agility and the momentum of deliverables. Best of all, we’re back to changing the rules of mobile. For example, we were the first mobile operator to allow customers to use their phones from abroad as if they were at home. And our financial performance is solid.’

This chapter has discussed what is becoming the Holy Grail of companies around the world: to be more agile in the face of a world where doing the same old thing is a threat to your very survival. It’s not easy becoming a connected organisation. But by following the principles discussed throughout this book you have a better chance of being one of the survivors. So, ask yourself:

- Do I support those that fail fast and learn or do I penalise failure?

- How committed am I to learning for myself?

- How well do I provide a role model to others as a learning professional?

- How bold am I?

- What holds me back if I hesitate to make brave decisions in response to changing circumstances?

Connected leader’s checklist

- Agility needs the strong spine of purpose, direction and values and the supple muscles of learning.

- You need a culture where innovation and improvement are valued and people feel confident to experiment without fear of failure.

- Ruthless prioritisation enables you to focus resources on the few things that matter most to customers.

Notes

1 Cirrus and Ipsos MORI (2015) ‘Leadership connections: how HR deals with C-suite leadership’, http://cirrus-connect.com/news/ipsos-mori-and-cirrus-launch-joint-research-project-6918#sthash.TEAIKQBu.dpuf (accessed 6 June 2015).

2 Heifetz, R., Grashow, A. and Lensky, M. (2009) The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press.

3 Manyika, J., Chui, M., Bughin, J., Dobbs, R., Bisson, P. and Marrs, A. (2013) ‘Disruptive technologies: advances that will transform life, business, and the global economy’, McKinsey Global Institute, May.

4 Siemieniuch, C. E. and Sinclair, M. A. (2008) ‘Using corporate governance to enhance “long-term situation awareness” and assist in the avoidance of organisation-induced disasters’, Applied Ergonomics, 39(2), 229–240.

5 Oxford English Dictionary, 7th edition (2012), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

6 National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (2011) ‘Sharing internal best practices’, Hamilton, ON: McMaster University.

7 http://startupquotes.startupvitamins.com/post/33415208650/we-dont-celebrate-failure-in-silicon-valley-we (accessed February 2015).

8 Zafar, N. (2011) ‘The 5 secrets of Silicon Valley’, The Atlantic, 4 August, 1–4.

9 Krebs, V. E. (2008) ‘Managing the connected organization’, orgnet, www.orgnet.com/MCO.html

10 Senge, P. (2006) The Fifth Discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization, London: Random House Business.

11 Ibid. (www.solonline.org/?page=Abt OrgLearning).

12 Garvin, D. A., Edmondson, A. C. and Gino, F. (2008) ‘Is yours a learning organisation?’, Harvard Business Review, March 109–116.

13 Milway, K. S. and Saxton, A. (2011) ‘The challenge of organisational learning’, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Summer, 44–49.

14 Denyer, D. (2013) ‘15 steps to peak performance’, Management Focus, Cranfield University, Autumn, 10–13.

15 Fletcher, J. K. (2004) ‘The paradox of post-heroic leadership: an essay on gender, power, and transformational change’, The Leadership Quarterly, 15(5), 647–661.

16 Stacey, R. D. (1995) ‘The science of complexity: an alternative perspective for strategic change processes’, Strategic Management Journal, 16(6), 477–495.

17 Uhl-Bien, M. R. and Marion, R. (2011) ‘Complexity leadership theory’, in Bryman, A., Collinson, D., Grint, K., Jackson, B. and Uhl-Bien, M. (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Leadership, London: Sage.

18 Denyer, op. cit.