Chapter 1

Why you need to know about connected leadership

Successful leadership in today’s complex and volatile environment is about being connected. Connected leadership marks a pronounced shift from the old model of hierarchical command and control to a new model of leading through influence. It relies on effective communication and connection across the organisation based on a consistent set of assumptions and beliefs.

Connected leadership makes a difference when these five interrelated factors come into play:

- purpose and direction

- authenticity

- devolved decision making

- collaborative achievement

- agility.

Old models are breaking down

As a leader today you may well be feeling a sense of urgency and pressure, but also frustration. Do you see people in your organisation constantly busy juggling all sorts of projects, but get the feeling that not enough gets done? Do new initiatives too often become bogged down in bureaucracy and a lack of accountability? Are other people frustrated? Is there a lot of noise and not a lot of output? Do you sometimes wonder whether the customer is really front of mind?

You can see that your organisation has to change the way it works with customers and deals with the threats of competition, complexity, regulation, globalisation. But putting in place glossy new transformational programmes just doesn’t seem to work – they don’t translate into the genuine connections between people and among teams that will make a real difference and get things done.

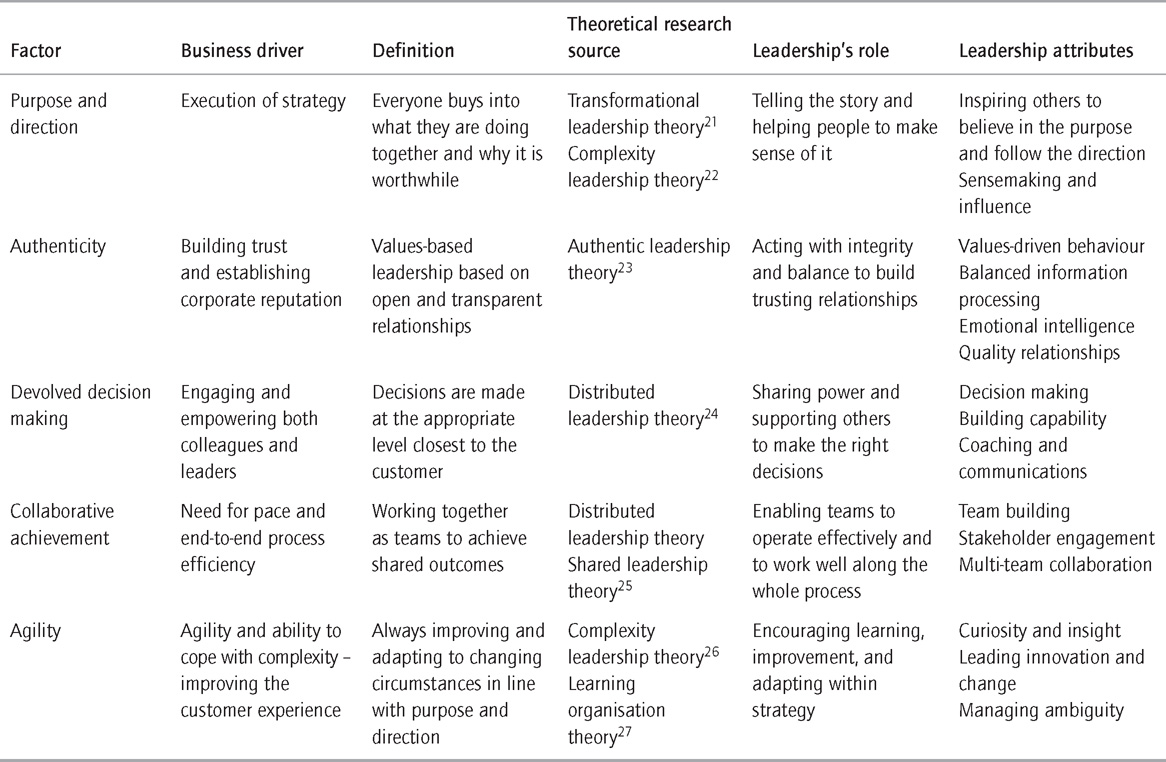

You are by no means alone. Many senior executives are trying to figure out how to make their businesses more agile in an environment characterised by volatility, uncertainty and discontinuity.1 Additional pressure comes from the widespread erosion of trust and reputation in several industry sectors, including banking and finance, services and retail, while both customers and colleagues are demanding more transparency and accountability. For many this is rooted in the upheavals caused by the global financial crisis, the associated loss of trust in corporate and governmental institutions, and consumer empowerment. As Figure 1.1 shows, research from GlobeScan has found that public trust in global companies has fallen to its lowest point since they began tracking this in 2001.2

figure 1.1 Public trust in companies at low levels

Source: www.globescan.com/news-and-analysis/blog/entry/trends-on-our-radar-for-2015.html

This has been further intensified by the pervasiveness of social connectivity and networking, as companies find everything they do is on global display. Customers want instant responses to complaints and questions – an immediacy that the hierarchical command-and-control models can rarely deliver.

The answer lies with us as leaders. Our role is to create organisations in which what we say and what we do is consistent, what happens internally is in line with what we write in our annual reports and what we promise to our customers is delivered. Our role is to embed an organisational ethos that encourages swift reactions to changing market conditions by inspiring everyone to act and adapt far more quickly than they have been used to.

Many of today’s leaders are well aware of what they need to do, highlighted by a research project among the leaders of FTSE 350 organisations (published in early 2015).3 In the research, conducted by Ipsos MORI and Cirrus, 65 per cent of respondents stated that their biggest priority was being more agile and 64 per cent said it was creating a stronger sense of shared direction.

So, where do you start? Today’s most successful leaders connect people across the organisation to strategic goals and to customers by developing a shared agenda through purpose, direction and values. They devolve decision-making responsibility and encourage a culture of collaboration and teamwork. They stimulate a high degree of empowerment and trust that each person and team will perform to the best of their ability. They increase agility through developing a learning culture that drives innovation and ruthless prioritisation. They are connected leaders – see Figure 1.2.

figure 1.2 Connected leadership framework

A new style of leadership

The discussion about leadership has moved beyond the archetypal big personality who runs the company and is the embodiment of its values and culture – the so-called ‘hero’ leader.4 Successful business renewal is no longer automatically seen as synonymous with leaders like the late Steve Jobs of Apple and Jack Welch of GE. The pronouncements and personalities of leaders like this seemed so integral to the success of their businesses that they often attracted as much attention as the products themselves. Yes, powerful individuals can generate fresh energy and develop a new sense of purpose. However, this style can cause too much of a focus on the individual heroic leader who motivates others to ‘save the day’ based on charisma and personal appeal. It might work for a time. The problem is that fissures can break open in the organisation once that leader goes, as happened at the UK retailer Tesco following CEO Terry Leahy’s departure. In fact, companies like Apple and GE have demonstrated the opposite, namely an ability to manage smooth leadership succession by developing leadership as an organisational capability rather than relying on the ‘hero’ at the top.5

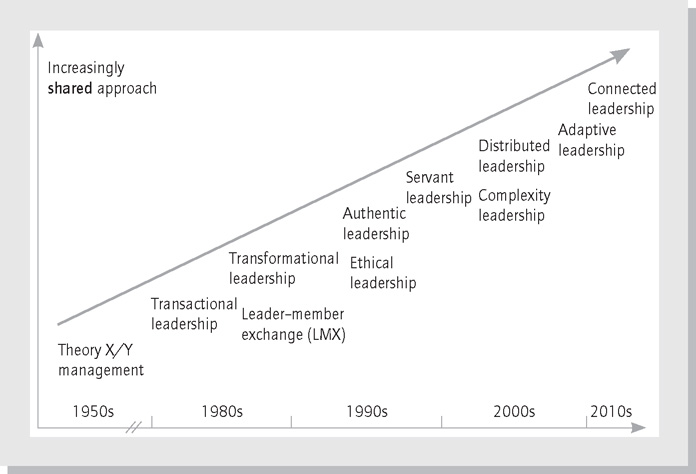

That is why, over the past 15 years, there has been more of an appreciation of the role of leadership as an act of shared influence to achieve collective objectives, which moves beyond a rigid hierarchical model. Leading research around the world points towards this shift, as we can see in Figure 1.3, with growing recognition of the power of shared leadership to deal with the increasingly complex and networked world in which we live.

figure 1.3 Evolving leadership theories

From a relatively centralised approach to power in the 1950s we saw the rise of the inspirational ‘heroic’ leader of the 1980s and 1990s, and then the emergence of ‘post-heroic’ leadership in the 2000s in the forms of authentic and servant leadership. Distributed leadership and complexity leadership theories in the 2000s took this to a further level of sharing power.6 I have created a coherent model that enables us to understand how the various theories have evolved and how they complement each other in responding to the needs of the networked unpredictable environment in which we now operate.

One of the earlier influential leadership theories was Theory X and Theory Y put forward by Douglas McGregor in 1957, based on two assumptions managers make about employees.7 Theory X suggests managers assume employees are inherently lazy and need close supervision, while with Theory Y managers are open to seeing employees as inherently self-motivating and seeking responsibility, so requiring involvement and trust to perform at their best. Connected leadership is consistent with Theory Y.

Transactional leadership focuses on how process and reward influence what followers actually do at work. In 1978, James MacGregor Burns described how the leader has the power to reward or punish the team’s performance and to train and manage when members are underperforming.8 This emphasis on the recognition and reward process is reflected in the emphasis on performance management in today’s HR culture. This emphasis is being questioned by some commentators as being too ‘transactional’ when there should be greater emphasis on having quality discussions to maximise motivation and performance. As we shall see later, connected leadership is certainly consistent with the emphasis on dialogue rather than a mechanistic connection between reward and performance.

In the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, transformational leadership,9 with its emphasis on the charismatic leader who inspires others to do great deeds,10 became fashionable. There is much value in the transformational approach, with its emphasis on setting and communicating a vision, as well as giving attention and managing one’s behaviour to engage followers in the leader’s direction. In connected leadership I echo the importance of these things, but with one key difference: it is less about the heroic leader and more about the shared process of leadership that really makes organisations successful in a sustainable way.

Similarly, connected leadership draws on aspects of LMX theory (leader–member exchange), which developed our appreciation of the importance of the quality of relationship between the leader and their team members.11 This line management relationship is certainly a critical influence on the level of engagement and resulting discretionary effort of followers, and the more connected each line manager is with the organisation’s purpose, direction and values, the more joined up the enterprise will be.

Authentic12 and ethical13 leadership both reflect the increased emphasis on values and behaviour in the 1990s. Connected leadership draws heavily on authentic leadership in particular, as personal and collective authenticity is a pre-requisite for the quality of trust that is required for connected relationships to work in practice. Authentic leadership suggests that leaders need to have high levels of self-awareness, a strong moral compass, the ability to make sense of information in a balanced way, and open and transparent relationships (I describe this more in Chapter 5). Servant leadership is also very consistent with connected leadership, reflecting the shift from the leader as hero to being the enabler of others.14

In the 21st century research into leadership has shifted to challenge the heroic model of the individual saviour riding to the rescue in favour of a more shared approach where many people can lead others across the organisation on a day-to-day basis to achieve higher levels of overall performance. Distributed leadership is a way of describing this in a practical way, with shared decision making within an overall framework of coordinated activity.15

Complexity leadership theory takes this further, by recognising that in the unpredictable world in which we now operate we need to create organisations that can adapt to changing conditions while retaining strong core processes.16 Connected leadership draws on both, as an integrated leadership approach based on the best research and in tune with the networked society in which we and our consumers live. It also draws on shared leadership theory, which emphasises team leadership and the shared nature of leadership as a process of influence, and on adaptive leadership, which emphasises the need for systemic change leadership in order to thrive in the complex world in which we operate.17

Connected leadership also reflects much of the thinking in the service profit chain, a business model that emerged from research into retail performance in the 1980s and which established relationships between profitability, customer loyalty and employee satisfaction.18 It also reflects more recent research which shows the relationship between customer experience and corporate reputation and how leaders collectively create the environment for success for colleagues and customers alike.19

Understanding connected leadership

Developing the connected organisation starts with you as the leader and how you influence others to establish and nurture the critical connections, both at the strategic level and locally in every team across the organisation. A leader cannot act in isolation. I believe we have to work with our colleagues to create a delicate balance between distributing power while retaining a strong core structure. If everyone is working with a consistent set of assumptions about ‘what great looks like’, they can in turn make the right decisions for customers, which drives loyalty and advocacy in the marketplace.

In the world of social media and instant news, this customer experience is often played out on a global stage with millions in the audience, exaggerating the effect of the connections – for better or for worse. Large retailers, for example, will typically have millions of followers on Twitter, meaning that one customer’s tweeted complaint can reach and influence millions of other customers within moments of a bad experience.

My research into large organisations, as well as my in-depth analysis of international research into leadership effectiveness over the past 20 years, has identified five key factors that contribute to a style of leadership suited to this connected world in which we live. Taken together these factors build the strong connections that enable an organisation to achieve its goals and ultimate purpose in our rapidly changing world.

The five factors are:

Purpose and direction

The first factor, and the one which is the foundation for the others, is purpose and direction. When people in an organisation have a common understanding of why they exist as an entity, a clear sense of what they are trying to achieve and the strategy to get there, there is a shared mission around which people can unite and flourish. It is up to you as the leader to help people make sense of this and how their roles relate to the purpose of the business. After all, people typically want to know that what they do at work has value, meaning and is something of which they can be proud. This is particularly true for ‘Millennials’, for whom meaning is typically a higher priority than for older generations such as ‘baby boomers’.

Authenticity

Leaders who act in a way that is in line with what might be called common standards of ethics, and who build relationships of trust and respect, engender stronger commitment among the people they lead than those who do not. Leadership based on balanced judgement and fairness of decision making engages colleagues and encourages them to develop effective, connected relationships across the organisation. It offers a behavioural framework to guide people to achieve the purpose and direction in a principled and morally satisfying way.

Both these factors act as the organisation’s ‘mission command’, a framework of priorities that leaves people free to operate, knowing they are not acting or behaving inconsistently with the overall aims and values.20 Note that context is key: these factors create a powerful context to help people to understand and embrace what’s special about your business, and how you develop and articulate this framework needs to reflect your organisation’s particular marketplace and goals.

Devolved decision making

The sharing of power across the organisation results in many decisions being made by people closer to the customer who can make them in the best interests of both the customer and the organisation. It is important to clarify who makes which decisions. So, while key strategic decisions are made centrally, service-oriented decisions are taken as close to the customer as possible. But for this to work well you need a climate where people feel safe to take a risk, comfortable to take responsibility for decisions and be supported, whatever the outcome.

Collaborative achievement

There has been increasing emphasis on effective team working in recent years as a better way to achieve great performance than through a more traditional command-and-control approach to work management. Collaboration means close working between teams as well as within teams, so that end-to-end processes work efficiently. Great team working is based on dialogue and mutual influence, with team members working closely with each other and reward structures reflecting collective merit more than individual performance. Companies such as John Lewis and Three have team-based reward systems that demonstrate collaboration in practice.

Agility

In an increasingly uncertain world organisations can no longer operate as if ‘one size fits all’. Agility requires that colleagues are allowed to adapt to changing circumstances, to share what they learn and to operate in a culture that supports experimentation without blame – to fail fast and learn as a driver of innovation and pace. Free movement of knowledge facilitates innovation and improvement, while people are developed to do their best at all levels.

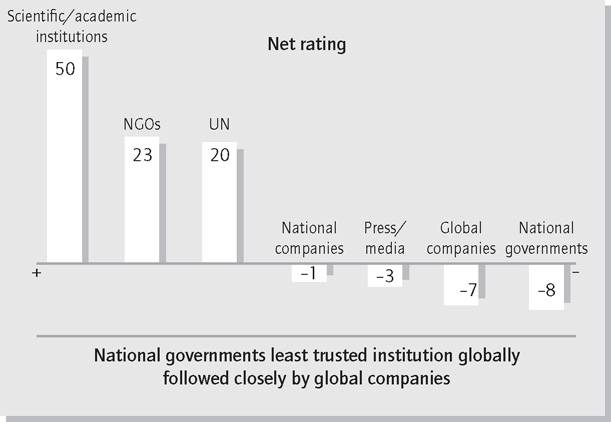

These five factors are summarised in Table 1.1. For each factor, you can see the main business driver that makes it a priority in today’s business world, a simple definition and the main theoretical source from leadership research. I also suggest what your primary role is as a leader and the attributes you need to demonstrate to be competent in this factor. I will explore these in more detail in the chapters that follow as I look at each factor in turn.

There is a sixth factor. The main pre-requisite for a successful transition to connected leadership is that the senior leaders of an organisation ‘get it’: that they are deeply committed to connected leadership in order to create a connected organisation and embrace what it means to be an active role model. Problems arise when people within the organisation aspire to make such a transition without commitment from the top.

It is very difficult to do this from the ‘bottom up’. History shows that at the national level revolutions can occur and radical changes to the leadership approach in countries do happen from the ground, such as in Poland and elsewhere in Eastern Europe during the 1980s. But at the company level, where corporate governance rarely requires leaders to be as accountable to employees as politicians are to the electorate, this type of evolution is generally unworkable.

What connected leadership looks like

- Leaders can communicate a clear purpose, direction and values as well as inspiring others to believe in that purpose and follow the direction.

- They act as authentic role models and stewards of the organisational purpose.

- They have a strong moral compass and are accountable for their behaviour.

- They are emotionally intelligent and self-aware, able to mobilise, focus and renew the collective energy of others.

- They are not afraid to share power so that decisions are made closer to the customer by people who are capable of making them in line with overall strategy and purpose.

- Collaboration and team working are emphasised as a better way to achieve great performance than through a more traditional command-and-control approach.

- Colleagues are encouraged to learn, to experiment and to adapt within the parameters of the organisation’s purpose, direction and values.

What it doesn’t look like

- A sense that the person at the top is always right.

- Leaders who believe what they say is more important than how they behave.

- Thinking that simply setting ambitious goals is enough to motivate people to give their best to achieve them.

- A lack of belief that building capability and culture is important to creating a truly connected organisation.

- Tenuous alignment between what they say is important and what they do – for example, mission statements about customer centricity are belied by budget cuts with direct impact on the customer experience when times are hard.

- Being overly controlling of even the smallest details.

Key benefits of connected leadership

The benefits of connected leadership are both tangible in terms of the impact on performance and intangible in that they create a high-performing culture which provides sustainable advantage in the marketplace. Specifically, the following benefits will arise from this approach:

- Creating an agile business able to respond quickly to changing customer needs and competitive pressures.

- Developing an empowered business where people take more ownership of decisions.

- Increased engagement so that people are keen to commit discretionary effort to the wider cause.

- Developing a learning business that is close to its customers and able to adapt to survive and flourish.

- Maintaining a strong spine of consistency that means everyone knows how to operate – freedom within a well-understood framework.

case study

Connected leadership at Mandarin Oriental

Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group is the award-winning owner and operator of some of the most luxurious hotels, resorts and residences located in prime destinations around the world. Its mission, ‘to completely delight and satisfy our guests’, began with the opening of its flagship property, The Mandarin, in 1963 in Hong Kong. The hotel, which was the tallest building on the island when it opened, soon built up an enviable reputation for service excellence, and instantly became a historic landmark – a status it still holds today.

In 1974 The Oriental in Bangkok, which was already acknowledged as one of the world’s most legendary hotels, was partially acquired by the Mandarin Group, giving the company two flagship hotels whose names represented the very best in hospitality. As a consequence, the two famous hotels joined to create the brand Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group.

Today the Group, with 12,000 employees, is a global luxury player with a presence in major cities and resort destinations around the world. Its aim is not to be the biggest hotel group in the world, but to be recognised as providing the very best in luxury hospitality.

A connected organisation

In many ways, Mandarin Oriental embodies the factors of connected leadership. The business has standard operating practices and a core set of standards, which are essential to delivering an outstanding experience to guests. There is clear yet minimal direction from the centre and individual hotels take responsibility for decision making close to the customer. For example, some hotels offer a relaxed style of service, others are more formal. Although marketing is directed from the centre, promotions are very localised. Furnishings and menus at each individual hotel reflect the local environment.

Overall, there is an effective balance between a strong centre which oversees group performance as a whole, and hotel managers who act autonomously within the core set of guiding principles and strong service standards.

The corporate head office is based in Hong Kong and the leadership team, or operating committee, get together every two to three months to take a company-wide view. Otherwise they focus on their functional areas such as food and beverage or rooms and quality. Chief Executive Edouard Ettedgui is deeply committed to the brand values and acts as a role model for the corporate vision and mission. He works closely with the operating committee and visits hotels regularly. While he is very aware of the detail of day-to-day activities, he focuses on overall strategy and vision and is regarded as an empowering CEO who believes in sharing responsibility across the organisation.

Jacqueline Moyse, Mandarin Oriental’s head of organisational development, elaborates on the central/local equilibrium: ‘While decision making at the centre is kept to a minimum and hotels are encouraged to have a lot of autonomy, they do operate within a framework of a very clear brand direction and a strong vision and mission statement which encapsulates the company ethos. That ethos is further underpinned by a set of guiding principles which is embedded in everyday operations. For example, when we open a new hotel we use certain standard operating policies and procedures but we give the individual management team freedom and responsibility to create a great customer experience at that hotel. We talk a lot about a sense of place. So when you experience our hotels you can see that, although there is a core set of standards, as hotels they are very different.’

This is part of the strategy which rejects the ‘cookie cutter’ approach taken by some of the very big hotel chains and instead believes that encouraging creativity, innovation and agility doesn’t fit with a hierarchical style of leadership.

The benefits of learning and listening

Mandarin Oriental recruits leaders and managers who can adapt to changing situations. Learning agility – the ability to apply existing knowledge to new challenges and swiftly create new solutions – is highly prized. There is a 90-day induction for every new employee, based around Mandarin Oriental’s mission and guiding principles. The induction also covers health and safety and quality service standards, which are among the highest in the industry. ‘We aim to enable people to learn the standards and also to encourage them to bring their own personality out,’ says Jacqueline. There are regular performance reviews in line with the organisation’s mission and values.

Mandarin Oriental continually monitors guest feedback in order to live its mission ‘to completely delight and satisfy our guests’ every day. Managers in each hotel meet every morning to review the previous day’s activity. Guest surveys, staff feedback and mystery shopping activity are discussed and acted upon. ‘This may sound quite regimented, but it isn’t,’ says Jacqueline. ‘We can see the creativity that comes from giving people freedom to act.’ The group also has a popular and well-used intranet where feedback, ideas and best practice are shared between hotels.

Collaboration is the norm within each hotel as well as across the entire business. As Jacqueline explains: ‘As well as devolving decision making within a framework, we work hard at building effective teams, and at working across silos such as finance, food and beverage, and brand communications. We ensure that every department understands the challenges that colleagues in other departments face. This helps us to provide exceptional customer service.’

Connected leader’s checklist

- We are living in a post-heroic era where ego has to give way to what’s best for the customer.

- Colleagues and customers expect a localised experience with consistently high standards.

- The five factors of connected leadership provide a framework for building a connected company when put into practice as a whole.

Notes

1 Cirrus and Ipsos MORI (2015) ‘Leadership connections: how HR deals with C-suite leadership’, http://cirrus-connect.com/news/ipsos-mori-and-cirrus-launch-joint-research-project-6918#sthash.TEAIKQBu.dpuf (accessed 6 June 2015).

2 www.globescan.com/news-and-analysis/blog/entry/trends-on-our-radar-for-2015.html (accessed January 2015).

3 Cirrus and Ipsos MORI, op. cit.

4 Badaracco, J. (2001) ‘We don’t need another hero’, Harvard Business Review, 79(8), 120–126, http://hbr.org/2001/09/we-dont-need-another-hero/ar/1 (accessed 1 August 2014).

5 Ulrich, D. and Smallwood, N. (2004) ‘Capitalizing on capabilities’, Harvard Business Review, June 2004, 119–128.

6 Uhl-Bien, M. and Marion, R. (2001) ‘Leadership in complex organisations’, The Leadership Quarterly, 12(4), 389–418.

7 McGregor, D. (1957) ‘The human side of enterprise’, The Management Review, 46(11), 41–49.

8 Burns, J. M. (1978) Leadership, New York: Harper & Row.

9 Ibid.

10 Bass, B. M. (1985) Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations, New York: Free Press.

11 Graen, G. and Uhl-Bien, M. (1995) ‘Relationship-based approach to leadership: development of leader–member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective’, The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247.

12 Avolio, B. J. and Gardner, W. L. (2005) ‘Authentic leadership development: getting to the root of positive forms of leadership’, The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338.

13 Kanungo, R. N. (2001) ‘Ethical values of transactional and transformational leaders’, Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 18(4), 257–265.

14 Greenlead, R. K. and Spears, L. C. (2002) Servant Leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness, Costa Mesa, CA: Paulist Press.

15 Spillane, J., Healey, K., Parise, L. M. and Kenney, A. (2011) ‘A distributed perspective on leadership learning’, in Robertson, J. and Timperley, H. (eds.) Leadership and Learning, London: Sage.

16 Uhl-Bien and Marion, op. cit.

17 Pearce, C. J. and Conger, C. (2003) Shared Leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership, California, CA: Sage.

18 Rucci, A., Kirn, S. and Quinn, R. (1998) ‘The employee–customer profit chain at Sears’, Harvard Business Review, January–February, http://hbr.org/1998/01/the-employee-customer-profit-chain-at-sears/ar/1 (accessed 11 September 2014).

19 Chun, R. and Davies, G. (2006) ‘The influence of corporate character on customers and employees: exploring similarities and difference’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 138–146.

20 Bungay, S. (2011) The Art of Action, Boston, MA: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

21 Bass, op. cit.

22 Uhl-Bien and Marion, op. cit.

23 Avolio and Gardner, op. cit.

24 Spillane et al., op. cit.

25 Pearce and Conger, op. cit.

26 Uhl-Bien and Marion, op. cit.

27 Senge, P. (2002) ‘The leader’s new work – building learning organisations’, in Morey, D., Maybury, M. and Thuraisingham, B. (eds.) Knowledge Management: Classical and contemporary works, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.