Chapter 8

Encouraging collaborative achievement

Achieving results through having high levels of collaboration based on team working, stakeholder engagement and multi-team collaboration is one of the main drivers of the connected organisation. In this chapter we examine how to maximise this more open and fluid style of working across organisational boundaries to achieve efficient and effective end-to-end processes.

We consider:

- why great teams outperform individual efforts, particularly when there is collaboration among teams

- how to create the right climate of collaboration by emphasising mutual respect and influence

- active team management

- encouraging a culture of collaboration.

Breaking down barriers

Jada was the head of HR for a major fashion retailer with multiple brands in its portfolio. The company had been an Australian institution for nearly half a century but recently it was struggling financially. The senior management team couldn’t understand it. The company had followed other retailers by going online, it had improved delivery efficiency and had even brought in top designers to create clothing that was on-trend and upmarket. But the number of repeat customers was dropping, and fast.

Jada knew that the business just wasn’t collaborative enough. There was a lack of shared knowledge and understanding across functions and the silo mentality was strong. If someone further down the supply chain wanted to speak to someone in design, for example, it would be difficult for them to understand each other’s opinions, so different were their separate experiences of the same company.

The company was also slow to market. There were fashion retailers now with new product development process times of as little as two weeks, from concept to the shop floor. It was a difficult time for any retailer, but especially one whose new product process took six months at best.

Jada realised that the company urgently had to rethink its strategic approach to collaboration and team working across all the brands and business units from the top down. The supply chain needed to be speeded up and barriers to a more collaborative way of working had to be broken down.

Why collaboration counts

It has been proven time and again that great teams outperform collections of talented individuals because collaboration knits the individuals together in the shared pursuit of the team’s goal.1 When teams are empowered to operate and cooperate with other teams across processes and break through bureaucratic silos, pronounced performance improvements are common. Built on the foundations of quality dialogue and mutual influence, teams can produce new answers to old problems and innovative ways to serve the customer even better by adapting quickly to changing circumstances.

According to Katzenbach and Smith, studies of team performance in more than 30 companies showed that members of high-performing teams share a meaningful purpose and experience high levels of commitment and satisfaction from being part of and working with the team.2 They work well together in an integrated way, while there is a high level of awareness and appreciation of each person’s individual strengths and complementary skills. In addition, the team shows a high capability for solving its own problems, there is mutual accountability and a willingness to act and, most importantly, the team produces quality results.

This echoes Belbin’s research, which showed that effective teams consistently outperformed groups of talented individuals in a range of tests and activities.3 Each successful team had a blend of different personal styles and skills which were complementary and aligned with the shared purpose and direction. The talented individuals, by contrast, competed with and failed to listen to each other, resulting in sub-optimal performance overall.

A collaborative ethos encourages people to work together, not just by playing their appropriate role within a team but by working with colleagues across business units, brands and functions. This aligns the decision-making process across the business. Increased levels of collaboration support distributed influence and vice versa. As members of the organisation build more capability to work together across boundaries, combined with devolved power to accelerate decisions and actions (as discussed in the previous chapter), the organisation becomes more agile and tends to achieve more.

Understanding the different stages of team formation

In their key work, The Wisdom of Teams, Katzenbach and Smith charted what they describe as the team performance curve, which shows the gradual stages in the growth of teams as they move from a straightforward working group to a fully fledged high-performance team.4

- The working group. This is a group for which there is no significant incremental performance need or opportunity that would require it to become a team. The members interact primarily to share information, best practices or perspectives and to make decisions to help each individual perform within their area of responsibility.

- Pseudo-team. This is a group for which there could be a significant, incremental performance need or opportunity, but it has not focused on collective performance and is not really trying to achieve it. It has no interest in shaping a common purpose or set of performance goals, even though it may call itself a team. Pseudo-teams are the weakest of all groups in terms of performance impact.

- Potential team. This is a group for which there is a significant, incremental performance need and that really is trying to improve its performance. Typically, however, it requires more clarity about purpose, goals or work products and more discipline in hammering out a common working approach. It has not yet established collective accountability.

- Real team. This is a small number of people with complementary skills who are equally committed to a common purpose, goals and working approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.

- High-performance team. This is a group that meets all the conditions of real teams and has members who are also deeply committed to each other’s personal growth and success. That commitment usually transcends the team. The high-performance team significantly outperforms all other like teams and outperforms all reasonable expectations given its membership.

In the case of a global consumer goods company I worked with, the CEO set up a global leadership team representing all the main businesses and functions across the organisation to increase levels of shared influence and collaboration throughout the organisation. This forum became the role model for collaborative working, with brand groups working together and functions and brands developing joint business plans. Through this process the business has become more agile and able to share scarce resources more effectively, as well as being more responsive to local markets.

While developing high-performance teams is a big step in establishing a more collaborative culture, it is the extent to which they are encouraged to operate interdependently across the business that can unite the organisation in pursuit of shared goals and have a significant impact on performance.

A particular leadership challenge has emerged over the last few years as teams have become more virtual, spread across locations and time zones rather than being co-located. A study by management consulting firm McKinsey in 2006 found that 80 per cent of the executives surveyed said that effective coordination across product, functional and geographic lines was crucial for growth.5 Yet only 25 per cent described their organisations as ‘effective’ in sharing knowledge across boundaries. This was despite spending heavily on collaborative software. Technology alone is rarely the answer, but it can provide a platform for collaboration if the human aspects of team working are in place. In both Xerox and Shell, engineering communities of practice across widely dispersed locations used technology to share learning in order to improve engineering performance. The results were significant gains in engineer efficiency and increased levels of collaboration among the engineers in areas as diverse as time to fix photocopiers (in Xerox) and oil exploration drilling efficiency (in Shell).

In order to make virtual teams and collaboration work in practice you need to work hard at communicating, having an explicit purpose for meetings and communications to highlight their relevance, and seek to combine virtual working with face-to-face meetings and team events.

The human desire for community

The ability of the team to achieve more than the sum of its parts is rooted in the basic human desire for community. It explains the altruism and identification with goals which often connect people who join localist initiatives. The World Health Organization’s definition of community below is a helpful insight that organisations need to operate ‘with the grain’ of human aspiration and motivation rather than through an outmoded command-and-control model.6

- ‘“Community empowerment” refers to the process of enabling communities to increase control over their lives. Communities are groups of people that may or may not be spatially connected, but who share common interests, concerns or identities. These communities could be local, national or international, with specific or broad interests.

- “Empowerment” refers to the process by which people gain control over the factors and decisions that shape their lives. It is the process by which they increase their assets and attributes and build capacities to gain access, partners, networks and/or a voice, in order to gain control. ‘Enabling’ implies that people cannot be empowered by others; they can only empower themselves by acquiring more of power’s different forms.7 It assumes that people are their own assets and the role of the external agent is to catalyse, facilitate or ‘accompany’ the community in acquiring power.’

The key thrust of this definition is that people can only empower themselves and that the role of the external agent (the leader) is to catalyse and facilitate the community in acquiring power. This links together the discussion in Chapter 7 about empowerment and the current discussion about collaboration across communities.

Organisational level

At the organisational level, in order to create collaborative achievement as a distinctive part of your company, first you need to create the right climate, second you need to invest in building strong teams and inter-team working and third you need to ensure that all teams are working for the greater good.

1 Creating the right collaborative climate

Collaboration accelerates organisational performance by knitting together business units and functions in pursuit of the direction and purpose, based on shared values and in an atmosphere of mutual influence. This optimises the performance of end-to-end processes so that they are as efficient and seamless as possible. It also orients the whole organisation towards the customer as the consumer of the value created by the various stages in the process.

At Zara, the local consumers’ buying patterns in Mumbai or Madrid, as reported by the store manager and their team every day, determine the product ordering and production priorities for the business. It is hard-wired into how the business operates, with a powerful combination of human collaboration, systems and processes creating a joined up and customer-centric business model. To accomplish this, everyone has to understand why they are doing what they are doing within the framework of the strategic purpose and direction. This higher-order understanding then guides what they do and every decision they take, as at Zara, while rewarding collaborative ways of working optimises team performance. For example, if people are clear that they are being rewarded for achieving certain outcomes that are in the best interests of the customer rather than fulfilling individual objectives which may not be consistent with the wider goals, they will act accordingly.

The flip side of this collaborative climate is an intolerance of behaviour that is counter-productive to creating the right environment. Strong teams do not tolerate disruptive individualistic behaviour. I remember Matthew Pinsent, the British multiple Olympic gold-medal-winning rower, describing the way the rowers in the crew held very direct, even brutal, post mortems after each training session to identify how to make the boat go faster. They were very specific and totally honest in expressing their views to each other about what worked and didn’t work. But they never took it personally, he assured me, as they had absolute faith that each crew member spoke only with the motivation to help the team to improve. The resulting gold medals speak for themselves.

Overcoming resistance from organisational silos is one of the main barriers to collaboration. As we saw in the previous section, human beings have a natural desire to be part of a community. This can, however, translate into tribal loyalties and behaviour, with an ‘us and them’ mentality present in functions or business units that have a stronger identification with their own unit than with the wider organisation. The leader’s role is to tackle this by drawing these local ‘tribes’ into the wider community of the organisation through creating sufficient momentum behind the shared direction, purpose and values – telling the story well and developing with people a shared sense of identity.

Organisational experts Drs Kevin and Jackie Freiberg offer a number of reasons why these tribes can become so prevalent in organisational settings, to the point where tribal loyalty supersedes any allegiance towards the organisation:8

- Tribes are a tool for self-preservation.

- Tribes provide identity.

- Tribes create emotional ties in a world where people have a deep need for belonging.

- Tribes are anchors, places people can call home; they provide safety and security.

- Tribal pride usually causes members to think their ideas and practices are superior.

- People are typically motivated by self-interest first, then allegiance to their tribe and finally loyalty to the common good of the larger organisation or community.

To break down these walls, they argue, you first have to understand just why the tribe exists by examining what they do, how they get things done, who benefits from them and so on. You are then in a better position to start finding ways to encourage a more collaborative mindset by getting them to buy into the organisational narrative instead.

This narrative should make it plain just what the fruits of collaboration are, such as the creation of new or improved services, better financial management and performance, competitive advantage, knowledge, good practice and information sharing, the ability to replicate success, better coordination of organisational activities and a more mutually supportive culture. You need to create a clear focus on the bigger picture, backed up by supportive relationships and agreed mutual benefits from a collaborative approach.

2 Build strong teams and strong inter-team working

One of the models we use in helping organisations develop more collaborative ways of working is the seven-stage Drexler–Sibbet team performance model.9 This can help you negotiate your way through the transition to an improved team-based and collaborative mentality.

- Orientation: why am I here? When teams are forming everyone wonders why they are here, how they might fit in and whether others will accept them. They need to know about purpose, team identity and feel a sense of membership. Problems emerge if there is any confusion about the purpose, any uncertainties about direction and any fear of failure or the unknown.

- Trust building: who are you? Next, people want to know with whom they will be working and their expectations, agendas and areas of competence. Establishing bonds of trust is essential. It is helpful to encourage mutual regard, being open and forthright and feeling that they can rely on each other. Signs of danger include overly cautious behaviour, mistrust or not saying what they really think.

- Goal clarification: what are we doing? The team’s more concrete work begins with clarity about goals, basic assumptions and vision. This includes setting milestones and measures of progress. Key to success is making assumptions explicit, with specific goals and a shared vision. Signs of unresolved concerns include apathy, scepticism and pointless squabbling or game-playing.

- Commitment: how will we do it? This is a pivotal stage in the team’s development. Decisions need to be made about how resources will be allocated, timing, who is responsible for what and how decisions will be made. The crux of this stage is a genuine commitment by team members to what the team is focused on achieving. Any lack of commitment can result in disowning responsibility and leaving decisions to others, or actively resisting progress.

- Implementation: who does what, when and where? As the work begins, timing and establishing a sequence of activities are paramount. Action plans with tasks, timings and objectives have to be articulated and followed. The clearer the overall purpose, the more scope there will be for individual creativity. While there are a number of ways to achieve this kind of integration, they all involve the creation of clear processes, alignment of the order of work and disciplined execution. Otherwise problems such as conflict and confusion, non-alignment of activities and missed deadlines can surface.

- High performance. When methods are mastered, a team can begin to change its goals and respond flexibly to the environment. This can lead to innovative thinking and behaviour and a surpassing of expectations. Team members are encouraged to be spontaneous in their interactions and feel a sense of synergy. Danger signs include taking on too much and being overloaded by commitments.

- Renewal: why continue? Teams are dynamic. People may get tired and members may change. This is the time to harvest all the knowledge and prepare for a new cycle of action. Keys to renewal include recognition and celebration, learning to be adaptable and finding sources of staying power. This could emerge from revisiting the overriding purpose and taking time to reflect on past progress and future direction.

Understanding the different stages of team formation is important because they each require different leadership involvement to facilitate the team’s progress. In addition, some groups will evolve at a steady pace, while others may get stuck at a particular stage. It is helpful for leaders to understand this process in order to behave in the most enabling fashion. Think about your own team and the teams on which you most rely in the business and consider where they are in their evolution. Based on this you can decide how to support them most effectively to move them along to the next stage. For example, leaders should focus on providing a secure environment by giving appropriate levels of direction and structure in the early stages of developing teams and collaboration, which can be characterised by confusion and uncertainty as well as defining objectives and getting to know each other. As you make progress, tensions can start to rise as people jockey for position and try to negotiate priorities. At this point leaders need to concentrate on facilitating the team discussions, managing conflict constructively and keeping the team or teams focused on their objectives.

It’s important but not easy

‘Team collaboration is really important. If people are operating in silos, cross-functional alignment won’t be good and you won’t get the best results. But the reality of running a business is that it can be unaffordable and unrealistic to put in all the extra effort and resources needed to get total alignment.’

Angela Spindler, CEO, N Brown Group plc

As people settle into new ways of working you will see team members finding more ways in which to collaborate with a spirit of respect and camaraderie. Here leaders need to focus on facilitating interpersonal issues, developing acceptable norms of behaviour and strategies for working together, clarifying roles and team structure, and building team spirit and motivation.

When you see a level of maturity in the collaborative ways of working, with people feeling largely settled and focused on the task at hand, the leader needs to allow team members the space to perform, ensure that the necessary resources are available, provide relationship and task support as appropriate, empower team members as necessary and keep an overall view on progress. The leader should provide feedback on performance to both individuals and teams and celebrate successes publicly.

While this approach can establish the groundwork for successful outcomes, unfortunately we don’t always have the luxury of time to build up these teams to operate at peak performance. As author and Novartis Professor of Leadership at Harvard Business School Amy Edmondson points out, given today’s speed of change, intensity of market competition and the unpredictability of customers’ needs and demands, sometimes problems demand swift action.10 So colleagues are brought together from across disciplines and geographies along with external specialists to achieve a particular goal quickly.

She sees an increasing number of companies in nearly every industry and sector working through what she calls ‘teaming’, with multiple teams of varying duration and constantly shifting membership pursuing moving targets. This can be a recipe for chaos, with both technical and inter-personal challenges, unless leaders focus on enabling technologies as well as reinforcing a culture that emphasises the direction, the purpose and the shared values so that everyone understands not only what they are doing but why. Yet if you have a clear process in place to support rapid team start-up, based on the stages above, you can get people together quickly and set them up for success to tackle particular issues effectively.

Collaborating in consumer goods

Our client is a large UK-based consumer products manufacturer. In 2012 the company moved from three divisions to two in an attempt to streamline the business. By 2013 it had reorganised this even further into a single unit, which was split into two sections: one was the wholesale production side of the operation and the other was the brands side. Our job was to help the organisation knit together these two sides of the business.

We worked with individuals and teams to help support a new collaborative way of working that would allow cross-functional processes to become more integrated and efficient. This came from two directions: first, we helped develop new behaviours and new ways of thinking among leaders and managers, and second, the company implemented process integration across the two old divisions. With some hard work and challenging conversations it has been completed successfully.

Cross-functional working was fundamental to this turnaround being a success. It resulted in an organisation that was clear about its strategy, clear about its values and clear about the behaviour of all colleagues. Our initial focus was to create a highly integrated board, so that as a cross-functional team they could be the role model for the new behaviours. There was a significant moment when the CEO changed his position from focusing on the process to focusing on the behaviour. When he realised that what they needed was a shift in mindset, and that the behaviours defined what that meant in practice, he enabled the rest of the business to explore and adopt the behaviours, which in turn made the end-to-end process work in practice.

3 Enabling teams to work for the greater good

Leaders need to be enablers, more often to be the facilitator rather than the provider of orders. The enabling function we looked at in the previous chapter captures the leader’s central role in embedding this collaborative approach into the culture and the mindset of the business.

It’s worth repeating here the three functions of complexity leadership which can support a move to a more connected way of working.11 The administrative function is about strong core direction, strategy, purpose and values. The adaptive function is about fluid ways of working more in tune with rapidly changing circumstances such as in local markets. The enabling function provides a balance between these two, building a culture of collaboration and mutual respect. When they are combined effectively, they give the organisation the ammunition to weather unpredictable and constantly changing environments.

As a leader you need to provide the enabler function in order to encourage collaboration across all the traditional boundaries clearly and openly. I would recommend you start with your own team so that you demonstrate what you want from others. Then, by listening and responding, by facilitating collaboration both within and between teams, you can help orchestrate quality dialogue and shared decision making across the rest of the business, in the best interests of the customer and the organisation as opposed to the localised interests of any particular team or function. It means that the organisation takes advantage of the capabilities and strengths of its people while ensuring careful coordination of effort for a common cause. You are no less involved, proactive and causing a change in ways of working than if you were directing operations from an ivory tower. But your focus is on getting people to step up, to work together, to resolve issues in an adult way, to think about the teams that rely on their outputs to do their work. You are the active enabler, not the passive observer.

From senior leaders coaching others to take decisions, through to local leaders encouraging learning and adaptation, these behaviours are about enabling the organisation to operate on the basis of accepting mutual influence, respecting others and making careful decisions that balance the organisation’s and the customer’s needs.

Finding the cause of conflict

This ‘Five Whys’ exercise can help you to try to resolve team conflicts. The five basic steps are:

- Gather your team and agree on the problem statement.

- Ask the first ‘why’ of the team: why is this problem happening? There will probably be three or four sensible answers. Record them all on a flipchart.

- Ask four more successive ‘whys’, repeating the process for every statement on the sheet. Post each answer near its predecessor. Follow up on all plausible answers and explore them further. You will have identified the root cause of the conflict when asking ‘why’ yields no further useful information.

- Among the dozen or so answers to the last asked ‘why’ look for systemic causes of the problem. Discuss these and agree what is the most likely systemic cause.

- After settling on the most probable root cause of the problem, develop an action plan as a team to remove the cause and replace it with a more positive way of working.

Note that it is likely that in a team context you will be dealing with interpersonal issues as much as process or system issues, so although this is a logical activity you may need to work with more emotional responses from people, which is fine. Treat everyone’s views with respect and stay in ‘adult’ mode. Putting emotional issues into a problem-solving format such as this can help to separate the behaviours from the personalities involved.

Your role as leader

So what does this imply for how you need to behave as a leader in the process? You need to be the role model collaborator and develop the art of listening in order to establish more respectful ways of working across the business, removing silos through example.

1 Be a collaborator

So what is your role in developing increased levels of collaborative achievement across your organisation? In my experience you will face some frustration as you embark or continue on a journey that is likely to be slower than you’d like if you are to take the majority of the organisation with you. Just as increasing the devolution of decision making requires a shift in culture, so the development of a more collaborative approach to working requires a shift in mindset and practice.

You can’t make people change their mindset – they have to choose to adopt new ways of thinking. What you can do as a leader is to introduce the idea, create opportunities for people to experiment with it in safety, and recognise and validate those who take risks with the new ways of working. It takes time and patience, as well as a healthy dose of determination, to overcome the cynics and the natural desire to bypass collaboration in favour of getting each particular problem that occurs solved as quickly as you can.

But the rewards for persisting and staying resolute can be impressive. ‘Groups with a high level of collective efficacy tend to set high group goals, develop good strategies, experience positive within-group affect, and select appropriate tasks, all of which ultimately enhance group performance’, according to research by Gully et al.12 Repeated research into team and collaborative ways of working shows the positive impact on organisational performance and end-to-end process efficiency.13 This means you get product to customers quicker, respond to changing market conditions quicker and see costs reduce quicker.

A key lesson I have learned through bitter experience is that your influence is enhanced when you show you are open to influence too. Behaviour begets behaviour, and if you want collaboration and mutual influence to pervade how your business works you need to demonstrate collaboration and being open to influence by others on a regular basis.

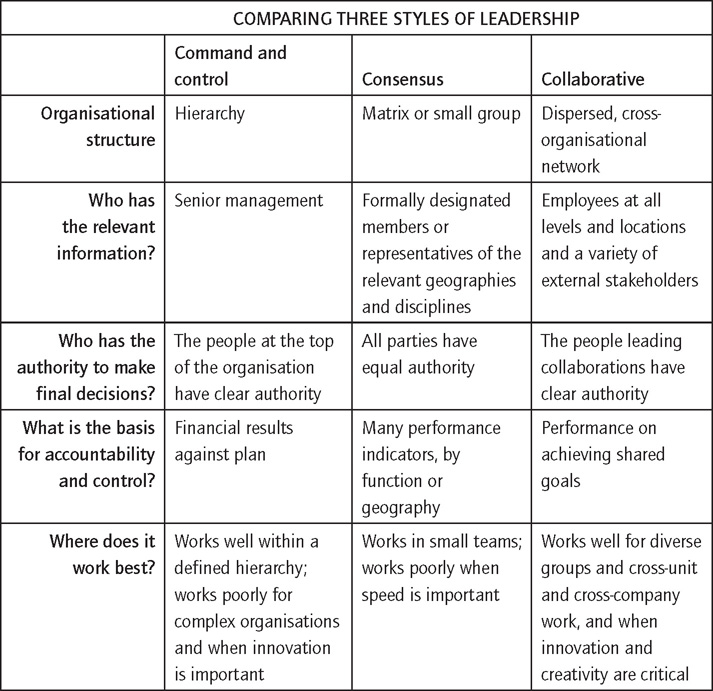

Figure 8.1 shows how a collaborative style of leadership differs from command-and-control and consensual leadership. As we seek to build a more connected organisation, with its ability to respond intelligently to external challenges and to work efficiently to drive performance internally, we need to dispense with the old style of retaining a command-and-control position. This was suited to more stable, predictable times when communications were slow and consumers knew less than those on the inside of corporations and governments.

In today’s networked society we need a new approach to leadership, one that is connected and in tune with consumers around the world. Consensus cannot provide the answer either, as it is slow and suited to small group working where speed is not a requirement. Only a collaborative, connected approach will achieve the level of pace and agility we need to compete in today’s and tomorrow’s markets.

A key characteristic of collaborative leaders is that they are able to look beyond organisational boundaries and take a wider view of their environment. If you can instil in leaders across your business the wider context in which they are operating, with the customer, the supply chain, the actions of competitors and the requirements of regulators, you will have established for them a set of reasons why they need to work effectively across the whole process, collaborating with teams in different business units or functions in order to deliver for the customer in a way that makes them buy from you rather than anyone else.

The persuasive power of collaboration

Getting people to appreciate the value of collaboration can be quite straightforward, argues Meghan Biro in Forbes.15 Simply ask them to list the five products or services they feel most passionate about: ‘The iPhone? Downton Abbey? Pinterest? Kit-Kat bars? Twitter? Got your list? Every single thing on that list was the product of a successful team collaboration. Sure, there may have been some half-crazy genius like Steve Jobs who supplied the leadership inspiration, but inspiration without collaboration is just a lot of great ideas that evaporate into the ether.’

2 The art of listening and showing respect

In a collaborative environment the traditional, ‘directed’ style of parent to child is counter-productive. Instead you have to learn to listen well, demonstrating respect for others and being open to influence in order to be able to influence others in return. Collaborating skills include:

- finding a combined solution when both parties’ concerns are too important to be compromised

- learning, e.g. testing your own assumptions and understanding the views of others

- merging insights from different people with different perspectives on a problem

- gaining commitment by incorporating others’ concerns into a decision

- demonstrating a desire to work with other people, especially when you want to build rapport or improve a difficult relationship by gaining trust.

This is about orchestrating a quality of dialogue among the various relevant parties. It is a dialogue that considers all views in the light of the best desired outcome as well as giving individuals a sense of being listened to. Maintaining this balanced approach in practice requires great communication skills, such as the ability to draw people out and to manage the competing demands of different functional groups.

I recall coaching one senior executive who was very collaborative most of the time, but when there were particular deadlines or the CEO was involved she tended to flip into a ‘parent panic’. She became directive, not listening, reworking the work of her team members and becoming overly critical of everyone around her. It was not a great place to be. It was not helpful, for example, when she overrode the opinions of one of her team with specialist expertise just because she felt he couldn’t see the bigger picture. My work with her focused on helping her to recognise this tendency and then to become able to avoid closed conversations. At its simplest a closed conversation is one where you have a preconceived idea in mind, you have a discussion and then you make a decision in line with where you started. In other words, whoever has the positional power gets their way. With this executive she closed down her team so that they were less proactive as a result and avoided making decisions without checking with her first. As she learned to change the routine she was able to rebuild their trust and their willingness to take some risks, but it took quite a while to get there.

Where she ended up was having more shared conversations, in which she demonstrated an appreciation of what was important and gave everybody the opportunity to weigh up various options in a more collaborative climate. This enabled them all to consider options and make a shared decision based upon achieving the end goal, rather than being driven by fear or the vested interests of what each party wanted or thought they needed from the decision. It led to greater engagement and commitment to the decision by everyone, so it was then more likely to get done, and get done successfully.

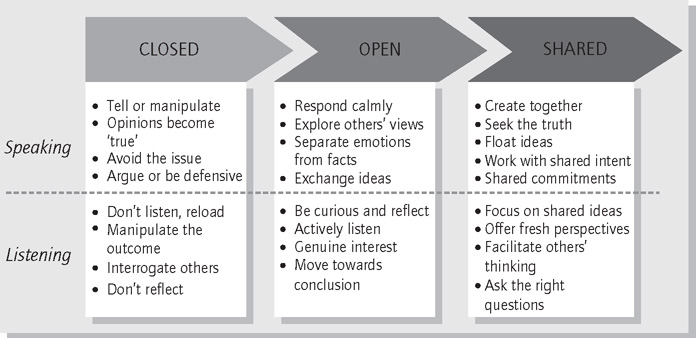

In Figure 8.2 we see a summary of the conversation spectrum, with the three levels of conversation, from closed to open to shared. As a connected leader you want to build from open to shared and ultimately have all your conversations at the shared level, where you create meaning together and you all seek the truth.

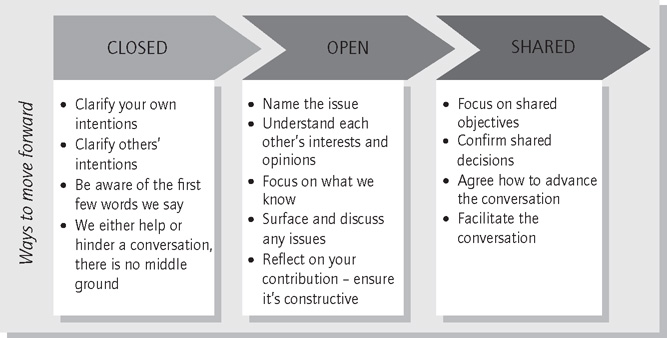

Figure 8.2 shows how to move along the spectrum from closed to open to shared conversations, both in terms of how you speak and how you listen to others. In Figure 8.3 we can see how to move the conversation forward, towards a more shared perspective. Wherever you start you can help to create a more connected conversation by adopting an adult style, seeking a positive outcome and maintaining your emotional balance. Remember that as a leader it is your responsibility to make every conversation in which you take part both positive and purposeful.

figure 8.3 A guide to creating more connected conversations

Source: Cirrus

Strategic listening from a CEO

Strategic listening is a powerful tool for the engaged leader, as Kevin Sharer, CEO of biotechnology business Amgen, said in an interview in the McKinsey Quarterly.16

- ‘As a senior executive – particularly if you’re responsible for a big function or division – you operate in a very complicated ecosystem with many sources of information that matter. In your mind, you need a picture of what reality is right now, with the knowledge that the picture is dynamic and ambiguous. That’s why it’s important to focus on what I call strategic listening: a purposeful, multifaceted, time-sensitive listening system that helps you get the signals you need from your ecosystem.

- ‘You’ve got to seek out these signals actively and use every possible means to receive them. I imagine the individual signals as mosaic tiles of information. No single tile paints the picture – and you never get all the tiles – but by assembling them you get a good idea of what the picture is. My method of gathering the tiles involves regularly visiting with, and listening to, people in the company who don’t necessarily report to me. I also read as much as I possibly can: surveys, operating data, analyst reports, regulatory reports, outside analyses, and so on. I meet with our top ten investors twice a year to listen, and at shareholder conferences I consider the Q&As very important. The key is making yourself open to the possibility that information can and will come from almost anywhere.’

case study

Collaboration at PayPal

Founded in 1998, PayPal has long been at the forefront of the digital payments revolution. Its global platform processed 4 billion payments in 2014 in more than 100 currencies. With 169 million active customer accounts, PayPal has created an open and secure payments ecosystem that people and businesses choose to securely transact with each other online, in stores and on mobile.

PayPal is widely admired as an innovative market leader. The company views collaboration and a focus on people as essential to ongoing innovation. The ability to collaborate is assessed during the recruitment and selection process, and is a focus of ongoing learning and development as well as promotion. PayPal actively builds a culture of collaboration through a balance of structured events and informal networking. There is a continual focus on team working, communication and shared decision making.

Mary Alexander is Senior Director, Human Resources, Europe, the Middle East and Africa at PayPal: ‘We operate in a matrixed organisation. Our people need to have compelling communication skills and the ability to form enduring relationships with colleagues over time. When there is a requirement to deliver quickly, people can draw on these relationships and collaborate to achieve shared goals.’

PayPal is viewed as an employer of choice and it has very clear criteria on what it takes to succeed in its organisation. ‘Collaboration is one of the skills we look for,’ says Mary. ‘We assess how well an individual can engage with others.’

Structured events include a quarterly networking event for all newcomers. ‘Developing relationships is really important,’ says Mary. ‘We get everybody together to share the tips and guidance that will help people succeed at PayPal.’

Regular regional or country calls, known as ‘all hands’, bring together people across all levels of the business to share news. Business units also have regular forums where there is open dialogue. These forums offer the opportunity to showcase new developments and share customer experiences. The top 80 European PayPal leaders also have monthly calls during which business updates and challenges are openly shared.

Employee engagement across Europe is 93 per cent. ‘I think part of the reason for that is we have very people-centric general managers who spend a lot of time on engaging employees and creating an environment of openness,’ says Mary.

Leadership development focuses on developing the effectiveness of teams and collectives as well as individual leadership effectiveness. ‘We look at the ingredients of what makes teams succeed and stand out. Part of that is about being able to work across boundaries and getting results through people working in different locations and across different time zones.’

Senior leaders are very accessible and invite feedback and insight from others. ‘People are unafraid to express a different point of view,’ says Mary. ‘We have an environment where we encourage people to say what they think, even if it’s negative. Senior leaders role model this behaviour.’

PayPal is also famous for its focus on customers. ‘Customers are at the core of what we do. Without them there’s no business at all. Our leaders are passionate about being a customer champion company, both for consumers who buy and sell through PayPal and for merchants who conduct their business with the help of PayPal.’ Operations teams collaborate with sales people and relationship and partnership managers to ensure a consistent, customer-focused approach. The European Sales Academy focuses on developing best practice in sales and relationship management. It helps build an understanding of how different products and services suit different customers, and enables PayPal employees to put themselves in the shoes of customers so they can engage with them in very relevant and engaging ways.

‘When we launch new products and services we ensure that there is a huge amount of internal employee experience during the development process,’ says Mary. ‘We also frequently welcome customers to forums at PayPal and there is a programme of senior executives spending time with customers to understand what they’re experiencing and to hear their voice.’

PayPal’s values underpin its collaborative culture. Everybody is expected and encouraged to have a point of view. ‘One of our values is “Debate, decide, deliver” and another is “Honest, open, direct”. People often refer to these values in day-to-day conversation. So for example, someone might say, “In the spirit of being open, honest and direct, I’d like to challenge that.” Living our values encourages a more open way of communicating and gets issues, perspectives and diversity of thought on the table.’

Here are some questions for you to consider and to prompt some notes for yourself:

- How does your leadership team function? How could it improve as a role model team?

- How does your company support team performance? Is there a structured, carefully designed process to ensure that teams work effectively?

- How collaborative is your organisation? Where could you focus attention for improving end-to-end collaboration?

Connected leader’s checklist

- We are stronger together. As you knit together the parts of your business and increase the levels of teamwork and collaboration, you are driving productivity and value in a positive direction.

- Human beings have a natural instinct to connect and collaborate as part of communities that give us identity and security. When we make the community the company we are on to something special.

- Start with your team and drive collaboration from there, across functions and locations, focused on serving the customer quicker and better.

Notes

1 Belbin, R. M. (2011) Management Teams: Why they succeed or fail, 3rd edition, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 18–19.

2 Katzenbach, J. R. and Smith, D. K. (1992) The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the high-performance organisation, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

3 Belbin, M. Belbin Team/Group Reports, www.belbin.com.

4 Katzenbach and Smith, op. cit.

5 Cross, R. L., Martin, R. D. and Weiss, L. M. (2006) ‘Mapping the value of employee collaboration’, McKinsey Quarterly, August, 29–30.

6 World Health Organization (2009) ‘7th Global Conference on Health Promotion: Track themes’, October, www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/7gchp/track1/en/ (accessed 17 June 2015).

7 Laverack, G. (2009) Public Health: Power, empowerment and professional practice, 2nd edition, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

8 Freiberg, K and Freiberg, J. (2014) ‘17 strategies for improving collaboration’, www.freibergs.com/resources/articles/accountability/17-strategies-for-improving-collaboration/ (accessed 17 June 2015).

9 Drexler, A. and Sibbet, D. (2008) ‘Team performance model’, www.grove.com/site/ourwk_gm_tp.html (accessed 17 June 2015).

10 Edmondson, A. C. (2012) ‘Teaming on the fly’, Harvard Business Review, April, 3–14.

11 Uhl-Bien, M. R. and Marion, R. (2011) ‘Complexity leadership theory’, in Bryman, A., Collinson, D., Grint, K., Jackson, B. and Uhl-Bien, M. (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Leadership, London: Sage.

12 Gully, S. M., Incalcaterra, K. A., Joshi, A. and Beaubien, J. M. (2002) ‘A meta-analysis of group-efficacy, potency, and performance: interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 87: 819–832.

13 West, M. A. (2012) Effective Teamwork: Practical lessons from organisational research, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

14 Ibarra, H. and Hansen, M. T. (2011) ‘Are you a collaborative leader?’, Harvard Business Review, July–August, 68–74.

15 Biro, M. M. (2013) ‘Smart leaders and the power of collaboration’, Forbes, 3 March 3, www.forbes.com/sites/meghanbiro/2013/03/03/smart-leaders-and-the-power-of-collaboration/ (accessed 20 February 2015).

16 McKinsey & Company (2012) ‘Why I’m a listener: Amgen CEO Kevin Sharer’, McKinsey Quarterly, April, 3.