Chapter 7

Devolving decision making

Devolving decision making is a critical element in making the transition to a more distributed and connected style of leadership. It’s also one of the more difficult, since it is natural for leaders to want to retain power in an organisation in order to control outcomes.

In this chapter we look at why pushing decision making further towards the customer is becoming such a prominent issue and how it plays out at the organisational level. An empowered culture and engaged colleagues are at the heart of this transformation, which needs to be based on providing sufficient management information, robust processes, creating a climate of trust and building capability.

Rethinking the balance of power

A husband and wife team, Jack and Rebecca, ran a medium-sized hotel on the outskirts of San Francisco in the US. The hotel was part of an international chain owned and run from London in the UK. The company was very patriarchal, having been in the hands of the same family since its founding in 1924. It wasn’t a luxury hotel chain by any means, but it was well known. Its average prices and better-than-average service and product were what had sustained it over the years. But there was a problem.

The company owned hotels from California to Moscow and they were designed and run in the same way. In the early years visitors had enjoyed this approach because they could experience a consistent room and service wherever they travelled, regardless of where they were in the world. Predictability of service was something on which the company prided itself. Recently, however, customer numbers were slipping – they just weren’t coming back.

The trouble was that the company wasn’t reacting quickly enough to a rapidly changing business environment. Some in the company even suggested that the founder’s great-grandson, now in charge, was incapable of running the company. Small boutique hotels had been set up in nearly every city where the company was based and these hotels provided an interesting, more locally attuned (and often cheaper) alternative to the same-brand hotel chain.

Jack and Rebecca knew they needed more power over the decisions about how to run the hotel in San Francisco. They wanted to choose some of their own furnishings and fittings and were keen to start sourcing food ingredients from local producers in order to create a better customer experience. While the CEO knew there was a problem and realised he had to cede more control to the local managers, he didn’t know where to begin. He had some serious thinking to do about how to evolve the business in this new and more customer-centric environment.

Why decision making needs to be devolved

Devolving decision making is one of the five key factors identified as drivers of success in creating a more agile and customer-centric business. Moving to a more distributed form of leadership helps create the connections that drive agility and a differentiated customer experience. One of the keys to success is empowerment, a word used frequently but which in my experience is often misunderstood and applied ineffectually.

The Business Dictionary defines empowerment as ‘a management practice of sharing information, rewards, and power with colleagues so that they can take initiative and make decisions to solve problems and improve service and performance. Empowerment is based on the idea that giving colleagues skills, resources, authority, opportunity, motivation, as well as holding them responsible and accountable for outcomes of their actions, will contribute to their competence and satisfaction’.1

I view it as creating a more intelligent organisation: one where people feel confident and competent to make decisions on a more regular and consistent basis, factoring in local conditions as well as the overriding purpose and values of the organisation. Devolved decision making is fundamentally about enabling decisions to be made closer to the customer that relate to the customer and coordinating these decisions within a strong framework. This gives people the flexibility and freedom to operate, confident that what they are doing is in line with the corporate strategy and values.

I see more and more companies grappling with this issue as they confront a marketplace of increasingly empowered consumers. We examined the rise of this ‘new consumer’ in Chapter 2 in the context of the networked society and the arrival of the Millennial generation. It is getting genuinely harder to please customers, not only because they are much more sophisticated about what’s available, and on a global scale, but because they also want to be treated as individuals, even in a mass marketing context. They are interested primarily in the benefits to them, as customers, and are swift to spot any approaches that are seen to be of benefit only to the producer. Many are also interested in the higher purpose and social impact of the producer to ensure that they, as consumers, are ‘buying ethically’.

Customer expectations of openness and transparency are high. Social media and digital communications enable customers to provide instant feedback – and they anticipate an instant response. Negative anecdotes get shared and amplified. The official story of a business or product lives in an increasingly contested space and any gap between the official story and actual behaviour is spotted quickly and amplified through social media – often with a damaging impact on financial performance.

As well as individual companies, whole industries are undergoing change relating to increased distribution of leadership. For example, in the UK rail industry there is a regulatory requirement for the rail infrastructure provider, Network Rail, to lead a culture change in the industry to one of partnership and customer centricity, based on a devolved structure. This is part of a strategic review of the way it operates, with an explicit commitment to introduce more devolved ways of working in the future. This is recorded in the CP5 notice of the Office of Rail Regulation: ‘Network Rail has made important changes in its internal structure, moving more responsibility away from the centre towards its devolved routes, and making changes to how it works with the wider industry in terms of alliances with train operators and more partnership working with suppliers.’2 Network Rail has created challenging leadership development programmes to help leaders at various levels to support the ongoing transition to more distributed leadership and ways of working.

Hence there is a need to become more agile through embedding a strong sense of colleague empowerment. The concept of empowerment has been around for many years, but it is less common in practice. The empowerment scenarios I see most often are partial or uncoordinated – in some organisations it is seen as a good principle, but in practice there is more centralisation of decision making, and in others it is left to individual managers to decide on how much they share decision rights with their people. Real empowerment involves a more concerted and cultural shift than either of these scenarios. According to Spreitzer, empowerment is a psychological state that encompasses four aspects of how people perceive their work:3

- Competence: an individual’s belief in their capability to be effective.

- Impact: the degree to which an individual can influence strategic, administrative or operating outcomes at work.

- Meaningfulness: the value of a work goal or purpose, judged in relation to an individual’s ideals or standards.

- Self-determination: an individual’s sense of having choice in initiating and regulating actions.

These aspects of empowerment act together to foster a proactive, self-confident orientation towards one’s work. As a leader you can create the climate where this is more likely to happen through demonstrating the authentic leadership behaviours we discussed in the previous two chapters in order for colleagues to feel trusted.4 The benefit of empowerment is that it has a positive impact on follower outcomes such as engagement, commitment, involvement, productivity and performance at both the individual and the team levels.

So if you want to create an environment where people feel confident and competent to make decisions and act in the best interests of both the customer and the business, you need to satisfy all four of the aspects listed above. Let’s now consider what this looks like in practice at the organisational level.

Organisational level

1 Putting empowerment in context

Devolved decision making is closely allied with the thrust of modern politics in many developed countries of pushing decision making as close to the citizen as possible. This emphasis on local autonomy is fundamentally a question of authority: who is best placed to make the most effective decisions about their lives?

The concepts of localism and subsidiarity can take many forms. They have a long history in the US, for instance, from the balance of power between federal and state governments, to town hall meetings which are able to decide on a range of important local issues. In many countries the idea of local power ranges from, for instance, the support of local production and consumption of goods (such as the rise of ‘farmers markets’) to the pressure from many regions to run their own affairs (such as Scottish devolution). The internet has only exacerbated this trend with people’s ability to make connections based on shared interests wherever they are, and to form instant pressure groups to react to any perceived transgressions from governments or business.

It goes to the heart of transactional analysis discussed in the last chapter, where traditional parent–child relationships, such as centralised ‘command-and-control’ leadership, are being replaced by a more adult–adult approach. Empowered colleagues (who are also empowered citizens and customers) are trusted to do the right thing within the overall purpose and direction of the enterprise.

If you look back to the history of leadership theory in Chapter 1, you will see how closely this resonates with the move away from the ‘heroic’ leader to a more distributed style of leadership. It reflects the need to create organisations that can nimbly adapt to changing conditions at all market touch points while retaining strong core processes. It is helpful to see the type of organisation we need to become going forward as a ‘complex adaptive system’, which is able to survive and flourish in fast-changing and uncertain environments by adapting quickly to changing circumstances to survive. This sort of system is able to deal with changes as they occur, but in a coordinated way. We can describe this as an ‘intelligent hierarchy’, where a leader, or group of leaders, uses the skills and expertise within the business to best effect through distributing the leadership role in a systematic and mindful way to create more intelligent functioning across the business.5

Dr Mary Uhl-Bien, an influential management writer on complexity leadership, relational leadership and followership, has identified three functions of leadership that are helpful in understanding devolved decision making: the administrative, the adaptive and the enabling.6 When these functions are combined effectively, they create balance in the organisation so that it can succeed in unpredictable and constantly changing environments.

- The administrative function is associated with the bureaucratic elements of the organisation and reflects traditional management processes and functions aimed at driving business results. According to Uhl-Bien, this function recognises that although organisations are bureaucracies, they don’t have to be bureaucratic. Having a strong sense of purpose, direction and a clear operating model are part of this function.

- The adaptive function describes the informal leadership process that occurs when people and teams work together to generate and implement novel solutions to organisational challenges. This is often at the edge of the organisation, closest to its customers and competitors, where local decisions can make the difference between success and failure.

- The enabling function – because the first two functions work in dynamic tension with each other, there is an important role for this third function. It balances the need for a strong core with the need to stimulate innovation, creativity, responsiveness and learning to manage continuous adaptation to change. As those further away from the senior level gain more power to make decisions, it is up to leaders to enable those people to make great decisions while ensuring that the overall process remains consistent.

It is helpful to consider in which functions your business is strong or less strong. If it has strong processes and controls in place, and clear alignment across the business with your overall strategic direction, it is likely to be strong on the administrative function. If it has high levels of local innovation, customer service and entrepreneurial flair, it is likely to be strong on the adaptive function. If it is strong on one of these but not on the other, the likelihood is that it will not be strong on the enabling function, which has the role of maintaining a healthy culture that can balance the need for a strong core with a locally adaptive periphery.

Interestingly, in the research conducted by Ipsos MORI and Cirrus in 2015 (see Chapter 3), the priority CEOs gave to the connected leadership factor of devolved decision making was the lowest compared with the other four. The tension is obvious: while CEOs may recognise the value in principle of leading an organisation that operates with an empowered culture, where people are able to do what’s best for the customers within the framework of direction, purpose and values, their preference is for decisions to be mandated from the top to ensure control and the assurance of consistent execution. But the subsequent lag in action can cause reduced agility and tends towards increased bureaucracy.

While some businesses might argue that economies of scale dictate a more rigid approach – fast-food franchises, for example, to ensure consistency of customer service – to me this is about creating an environment in which organisations can be agile, customer-centric and responsive to local markets in the increasingly volatile world in which we operate. Leaders can create a culture where people are able to make the appropriate decisions on a consistent basis taking into account local conditions within the context of the overriding aims and values.

This also has a considerable impact on levels of employee engagement, the importance of which has been studied since the 1920s, as well as in reverse, whereby engaged colleagues are more likely to feel empowered and make sound decisions in the best interests of the business. Studies have consistently found a strong correlation between employee attitudes in the workplace and performance. The Institute for Employment Studies (IES)7 states that the definition of employee engagement is ‘a positive attitude held by the employee towards the organisation and its values. An engaged employee is aware of business context and works with colleagues to improve performance within the job for the benefit of the organisation. The organisation must work to develop and nurture engagement which requires a two-way relationship between employer and employee’.

According to the IES, the strongest driver of employee engagement is a sense of feeling valued and involved, which can be influenced by an employee’s development, their relationship with their manager, the communications they receive, how fairly they feel treated and their involvement in decision making.

The beneficial effect of employee engagement

The benefits to the organisation of high levels of employee engagement include improvements to financial performance, customer loyalty and employee productivity. In one study of financial performance,8 Towers Watson looked at 50 global companies over a one-year period, correlating employee engagement levels with financial results. The companies with high employee engagement had a 19 per cent increase in operating income and an almost 28 per cent increase in earnings per share.

In the authoritative and widely researched MacLeod Report, ‘Engaging for success’, carried out for the UK government and published in 2009, the authors concluded definitively that many of the drivers of and barriers to engagement appeared to be closely related to effective leadership.9

2 Agreeing the structure of decision making

It is important to provide a clearly understood framework within which you can empower people. Decentralisation with a laissez-faire style of management can have serious drawbacks, such as duplication of resources, lack of cost control, decisions not in line with the company’s strategic direction and inconsistency of execution. The clearer you are about the direction and purpose and the values, the more you can give colleagues the flexibility to use their own judgement, safe in the knowledge that they will do the right thing because they are well aware of the wider mission.

In one international business with which I worked, there was much discussion about the benefits of empowerment, both with senior leaders and with the HR team, but actually putting it into practice proved too big a challenge. What I observed was a senior team who prized control over the business more highly than the potential performance benefits of creating a culture of empowerment. The CEO actually admitted that he had achieved success by trusting himself to get things done and that he found it hard to delegate decision making more widely across the business. The result was a more compliant, less nimble organisation.

It certainly takes time and persistence to create the environment where people are confident to take on the increased responsibility and for some perceived risk that comes with empowerment. In a global multi-brand business I worked with, the chief executive was determined to shift to a more distributed approach to decision making along the lines of the ‘intelligent hierarchy’ mentioned earlier. He worked hard to engage his senior colleagues to get more involved in determining the strategic direction of the business by encouraging increased dialogue between leaders of the brands and support functions to achieve more ‘joined-up’ thinking and decision making. At the same time he strongly reinforced the fact that the purpose and values were not negotiable. The senior team then involved more and more tiers of colleagues in defining where there were opportunities for more devolved decision making, building their confidence in the process as they went. Creating the right mindset across the business gradually resulted in increasing maturity and higher quality of decisions being made in areas as diverse as product development, IT systems and market development.

The military understands this need to find the right balance between central control and local decision making, based on ‘mission command’. Officers in the field need the freedom to act within a framework set by the generals in advance, based on clarity of mission and the acceptable parameters of flexibility. This is in accord with the principles first espoused by the founder of what became total quality management, W. Edwards Deming. After studying what had happened to Japanese industry after the Second World War and how it was able to emerge from the devastation with such success, he noted the autonomy that employees on production lines enjoyed. If they found something wrong, they were able to stop the line and fix it. In both the military and Japanese business the balance between a highly efficient central administrative function and highly devolved decision making in areas where local judgement was required created a powerful and flexible organisation that could cope better with a highly unpredictable environment.

The role of organisational structure

Organisational structure as such is not necessarily an indicator of a more or less devolved leadership style. What looks like a rigid hierarchy could be one that is nevertheless highly empowered, while one with wider spans of control could still operate in a more centralised way with little discretion given to frontline staff. Having a particular structure that supports a more joined-up approach is more of an enabler than a driver. The key thing to bear in mind is that structure and strategy need to be aligned.10 The more your strategy requires adaptation to changing market circumstances such as competitive innovation, technology shifts, varying local consumer patterns and so on, the more your structure needs to embody the principles of empowerment.

If you are trying to evolve to a more empowered environment it’s helpful to consider the current lines of command. Where power is concentrated, for example, there could very well be managerial roadblocks when trying to devolve or share decision making. In one organisation I researched there were powerful unit heads who ran largely independent divisions, each in their preferred way. These ‘fiefdoms’ became a power bottleneck and devolved decision making did not go much beyond these heads until the CEO intervened and required a shift in approach. Two of the unit heads eventually decided to leave as they believed in a different, more controlling approach to management. Fortunately there was agreement among the rest of the senior team about how decision making should be devolved and that they wanted to build a more connected organisation able to adapt in a concerted way. This experience reveals the importance of mindset and how having a shared mindset at senior levels is a necessary pre-requisite to moving towards a more empowered type of organisation.

3 Providing effective management information

As I have stressed, devolving decision making takes real commitment. You need to decide just what information colleagues require to make effective decisions and provide it in an easily understood format. You also need to support them with coaching and regular feedback so that they develop the confidence and competence to make effective decisions, rather than letting them sink or swim. There can be a temptation for you to jump in when problems arise further down the line, which can invalidate the process of devolving decisions as it undermines the position you have created for those who are empowered.

How do you decide just what information should be shared and what kept central? My first observation is that more transparency and sharing of information is generally a good thing. In a connected organisation people are treated with respect and trusted to use information wisely. I have seen various reasons given for keeping sensitive company information secret, including the risk of it leaking to competitors (who might use it against you) or customers (who might feel aggrieved at the margins being made, for example), the notion that a family-owned business must keep most information confidential, and the idea that too much information may destabilise people if it is not always good news. I have also consistently seen great benefits in companies where information has been shared openly with colleagues, including people being able to make more informed decisions based on good data and feeling more trusted and involved, which tends to mean they are more likely to take ownership for outcomes.

So in deciding on levels of disclosure I would encourage you to be generous. The precise way you structure management information needs to consist of the following elements:

- Deciding what and how much information – e.g. financial, business intelligence, marketing, customer measures – so it can be shared to give as many people as possible access to information that is relevant for their role and for their understanding of how the business is performing.

- Deciding how to share information to make it relevant to people’s context and easy to interpret and use in decision making.

- Establishing a comprehensive monitoring and feedback system to ensure best results, sharing of insight and intelligent use of information in the best interests of the business, your customers and your colleagues.

It may be helpful to experiment with more disclosure and to get feedback from people about whether the information is useful and valued. You can explore with people what level, frequency and format of information is helpful and how to improve this over time. It is helpful to bear in mind that transparency helps build connectivity and at the same time too much or irrelevant levels of detail can be counter-productive.

Your role as leader

As a leader there are three particular ways you can assist the transition towards a more devolved approach to decision making. First, creating a climate of trust so that people feel safe to take risks. Second, having robust processes in place helps to retain the administrative strength of the whole business. The third way is through building capability among your colleagues so that they are well equipped to make intelligent decisions in the best interest of the business as a whole.

1 Create a climate of trust

The way you as the leader create this climate of empowerment for both individuals and teams is likely to have a significant impact on the extent to which you can successfully make the transition to a more connected way of working. This is as much about culture as it is about the decision-making process itself. Trying to encourage a more experimental, more risk-taking, more entrepreneurial environment, where people can try things out and fail, doesn’t work if everything is controlled centrally and people are punished if they get it wrong. You need to put in place a well-planned and carefully managed approach to set people up for success.

Many leaders struggle with this. As writer, marketer and speaker Kevin Daum argues in an article for Inc., if it was that easy, everyone would do it.11 His eight tips for a more empowered culture are summarised here:

- Ensure that communications are open and not just top-down. Give colleagues structured ways to convey their thoughts, feelings and observations.

- Reward self-improvement. Leaders need to help their colleagues to grow and develop. Money spent on management and personal development training will be just as incentivising as promotion and pay rises.

- Encourage safe failure. Many colleagues are, by their nature, averse to risk. Causing them to feel they need to be constantly looking over their shoulder or trying to second-guess your views will only exacerbate this. Give colleagues the opportunity to try things in a new way – but one that doesn’t potentially harm the business.

- Provide plenty of context. Leaders need to learn to share relevant information. Colleagues can’t possibly take action and make good decisions if they don’t make sure people know what they need to know when they need to know it. This needs to be set in the context of the shared purpose and direction.

- Clearly define roles. People who don’t know what they are supposed to do unsurprisingly don’t do it very well. They also need to appreciate boundaries and parameters within which they can operate. Roles and responsibilities have to be made plain.

- Require accountability. People need to know when they are meeting expectations and when they are not. They have to understand the consequences of failure to maintain accountability. They also have to see that others are being held to the same standards.

- Support their independence. Give people a chance to stretch out on their own and even lead others. Letting them make mistakes will build up their confidence and sense of empowerment.

- Appreciate their efforts. It’s well known that money is rarely the main motivation for people to do a good job. They want to feel appreciated. Saying ‘thank you’ is a simple but effective way to make people feel valued.

The ability to show appreciation plays an important role in encouraging people to take decisions. To be effective, the recognition needs to be given as soon as possible after the desired behaviour or achievement. I would also emphasise Daum’s third point above, about creating the sense that it is safe to fail, and that failing fast and learning from it is better than persisting with failing projects or repeating mistakes through lack of review. If you want people to take responsibility and make decisions you need to provide the psychological security that it is safe for them to do so, whatever the outcome. This means being clear about your appetite for risk in each context and coaching people to make appropriate judgements about the level of risk in each decision.

Making a difference

‘In an environment where there is a shared vision of excellence, where people can be the best that they can be on a daily basis, where they know what is expected of them and believe they can make a difference because they will be heard, they will make a difference. They will go beyond our expectations and great things will start to happen.’

Frederick W. Smith, Chairman & CEO, FedEx Corporation

2 Develop robust process

Decide who makes the decisions

You cannot hope to achieve empowerment and hence agility without devolving power. Good decision making depends on assigning clear and specific roles and being clear about who has the responsibility for which decisions – who has the decision rights. This sounds simple, but many organisations struggle to make quick decisions because lots of people think they are accountable – or no one does. In one organisation I see people with their diaries full of meetings, many of which they don’t really need to attend but they do anyway because they want to be involved in the decisions taken. There is a lack of clarity on who is responsible for any particular decision, so the net result is many people having a share in it.

It is helpful to consider the decisions you or your leadership team currently make and to determine which of these it is important that you make. If you stick to the principle that you should make only the decisions only you can make it may be that some of your current decisions are better made by others. I find that boards and senior leadership teams tend to make or be involved in too many decisions and that they have considerable scope to push decisions back into the organisation to where there are people with more expertise, time or responsibility to make these decisions. It can be quite difficult for senior teams or individuals to let go of decisions that they have been involved in for a long time, and it can be equally difficult not to take them back again at the first sign of a problem. But if you can push decisions back to the people who are best able to make them, and coach and support these people so that they make decisions in a way that gives you comfort, then you will have kick-started a more empowered approach and given yourself more time to concentrate on the decisions only you can make.

Try listing the decisions in which you are involved or which you take and tick the ones that do not need to be taken by you. Now place a name against each of the ticks to identify who is better placed to take each decision.

The RAPID technique

One technique we have used successfully is called RAPID. Adapted from Rogers and Blenko in Harvard Business Review, it gives leaders a method of assigning roles and involving the relevant people.12 The key is to be clear who has input, who gets to decide and who gets it done.

The letters correspond to five critical decision-making roles:

- Recommend. People in this role are responsible for making a proposal, gathering input and providing the right data and analysis to make a sensible decision in a timely fashion. Recommenders consult with the people who provide input, building buy-in along the way. Recommenders must have analytical skills, common sense and know the organisation well.

- Agree. Individuals in this role have veto power – yes or no – over the recommendation. Exercising the veto can trigger a debate between themselves and the recommenders, which should lead to a modified proposal. If that takes too long, or if the two parties simply cannot agree, they can escalate the issue to the person who has the ‘D’.

- Perform. Once a decision is made, a person or group of people will be responsible for executing it. In some instances the people responsible for implementing a decision are the same people who recommend it.

- Input. These people are consulted on the decision. Because the people who provide input are typically involved in implementation, recommenders have a strong interest in taking their advice seriously. No input is binding, but this shouldn’t undermine its importance. If the right people are not involved (and therefore motivated), the decision is far more likely to falter during execution.

- Decide. The person with the ‘D’ is the formal decision maker. They are ultimately accountable for the decision, for better or worse. They have the authority to resolve any impasse in the decision-making process and to commit the organisation to action.

Balanced decision-making process

Writing down the roles and assigning accountability are essential steps, but good decision making also requires the right process. Too many rules can cause the process to slow down, which creates bureaucratic ways of working and reduced agility. Problems in decision making can often be traced back to one of three trouble spots:

- lack of clarity over who has the ‘D’

- too many people in each role

- too many sources of input.

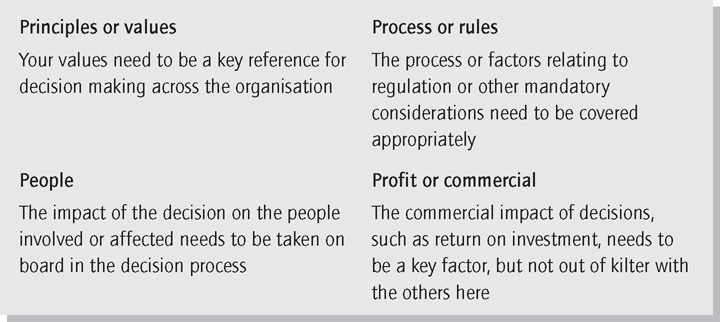

So it is helpful to ensure that the decision process is kept as simple and as balanced as possible. A helpful way to achieve a balanced decision-making process is to use a matrix that reflects the main factors you need to consider in the decision. These are likely to include the factors in Figure 7.1.

figure 7.1 Balanced decision-making matrix

Using this sort of matrix can protect you against excesses in any particular direction, whether it is people becoming too focused on the process and rules, or too concerned about the commercial implications without considering the effect of decisions on people and your culture.

3 Build capability

One of the pre-requisites for the introduction of connected leadership is capable managers who are able to take responsibility and to exercise it effectively. I would recommend you employ a systematic approach to building this capability across your management population to ensure it is in place consistently. It is also helpful to have a shared language. A technique you may find helpful is called ‘stretch–coach–review’, which gives leaders a constructive framework to apply devolved decision making through having the right conversations at the right time.

a) Stretch conversations

A ‘stretch’ conversation taps into discretionary effort by inspiring someone to commit to stretching performance goals that are aligned with the business strategy. Stretch conversations include:

- providing strategic clarity and direction

- agreeing expectations for performance

- analysing performance in relation to strengths, improvement areas and opportunities

- applying the principles of SMART objectives (specific, measurable, aligned, realistic and time-bound)

- looking for stretch opportunities that grow the business and its people.

How do you use ‘stretch’ conversations in practice? First, you need to prepare and set the conversation in the organisational context and strategy. Consider the motivation and ability of the person with whom you are speaking and ask yourself: do you really know what they are capable of and what they aspire to achieve? Do you know what really motivates them, their interests and values? Consider what you need to share with the individual and how you can challenge them to stretch themselves in line with your business goals. As Victor Hugo said: ‘There is nothing like a dream to create the future.’13

b) Coaching conversations

Coaching is the application of incisive questions that enable people to think for themselves and unlock their potential to maximise their performance. Coaching conversations are a purposeful two-way, adult-to-adult dialogue set in the context of a relationship based on trust. Through asking great questions you are seeking to develop increased levels of accountability and ownership in the other person or people. Coaching often includes diagnosing issues together and using collaborative problem solving to agree an appropriate course of action. Effective coaching conversations build self-belief, confidence and commitment in other people.

You can carry out coaching conversations whenever you are enabling someone to achieve their goals. What is the goal they have set out to achieve? Are they focused on the right priorities? Consider how you can help them to make sense of what is going on and to decide upon a clear and decisive course of action in the direction of their goal.

It is helpful for managers to realise that there are two very different reasons to coach: either to see an improvement in performance (performance coaching) or to expand someone’s capability to do new things (development coaching). Performance coaching can be quite directive about the issue, but it can also give quick results. It is often about helping people to make sense of what is going on, to identify options and to make an effective decision about which one to take. Sometimes you may need to adopt a commitment style (‘what I need from you is . . . ’) when there is a performance issue and you need the person involved to step up to making more informed and effective decisions. It often involves clear and unambiguous statements of what you require from a colleague in terms of performance, behaviour, attitude or commitment, followed by a conversation about what these requirement(s) mean in terms of their priorities and actions.

Development coaching, meanwhile, often is a more drawn-out and exploratory discussion. It is worth checking with yourself that you are investing time and energy into development coaching with the talent in your care, in order to accelerate their effectiveness and progress through the organisation. The more they can be involved in strategic decisions, for example, the more experience they will gain that will build capability for the future. Because development is typically in areas where the person has less experience or knowledge, you will sometimes need to give knowledge input to ensure they are able to participate effectively.

c) Review conversations

The review conversation involves you appraising with another person their progress and achievement in relation to objectives and goals. It creates opportunities to celebrate success, give and receive feedback, identify gaps, highlight learning and accommodate changing business priorities. Review conversations include:

- jointly reviewing quantitative and qualitative performance data

- giving frequent and specific feedback with respect

- balancing you pushing for more achievement and pulling from them more ambition

- adjusting objectives to changing business priorities

- recognising and celebrating success.

Take an opportunity to reflect ahead of these conversations. It is helpful to know what a ‘good’ outcome from the conversation would look like for you both. Prepare balanced feedback considering what has gone well with decision making and what has not gone so well, plus feedback from other stakeholders where appropriate. As you consider the next steps it can be motivating to consider together what this achievement now makes possible.

In extreme cases of underperformance the person may need the ‘tough love’ style, which is an approach where you need to be tough on someone in the short term in order to do right by them in the longer term. You might need to suggest a change to someone’s role or levels of decision-making responsibility if they are currently not able to deliver so that they have the opportunity to improve. Or you might need to get someone to refocus their career ambitions if they are clearly going to be frustrated trying to achieve the current goals. Either way, it’s important in such conversations to maintain respect and dignity for the other person.

case study

Devolved decision making in action at Zara

A great example of connected leadership in action is Spanish fashion chain Zara, part of Inditex, the world’s largest clothes retailer. Founded in 1975, Zara has 6,500 stores in 88 countries worldwide. It employs 120,000 people. The company has become renowned for its agility and customer-centric business model based on its powerful combination of highly centralised systems and devolved decision making. As founder Amancio Ortega has been quoted as saying: ‘You need to have five fingers touching the factory and five touching the customer.’

Devolved decision making

Local store managers enjoy a high degree of decision-making autonomy, which enables them to respond to the needs of customers in different areas. They are supported by in-house logistics and distribution channels set up to deliver products to stores and to customers quickly. A trailblazer of the ‘fast fashion’ movement, Zara can have a new garment in store just two weeks after it has been designed.

At store level, managers are empowered to make decisions close to the customer, helped by the most up-to-date digital technology. Managers receive a detailed sales and replenishment report every hour on a hand-held device. This valuable information enables them to order and receive clothes twice a week based on what they know local customers want. This supply chain excellence, with the organisational ability to deliver new clothes to stores swiftly and in small batches, is a source of significant competitive advantage.

Central coordination

Back at Zara HQ, the information about what’s selling is received across highly coordinated design, marketing, buying, production and planning teams. This enables further fast decision making – what to produce more of, what to withdraw, what trends are emerging now. Whereas many fashion retailers aim to predict what customers will want to wear months in advance, Zara utilises local store feedback and technology to observe what is selling well (and what isn’t) in real time and continuously adjusts design and production.

While Zara’s leaders have maintained that this speed and responsiveness are a higher business priority than costs, the strategy is so successful that the retailer is one of the most cost-efficient in the market. Because Zara can design and produce new garments so quickly, and in limited quantities, it collects an average 85 per cent of the full ticket price on its clothing, whereas the industry average is 60–70 per cent. Constant new stock in small batches also attracts more customers more often into stores and online to the website.

The result is that the retailer can save significantly on advertising. It spends just 0.3 per cent of its sales on advertising, compared with an industry average of 3–4 per cent. In addition, its expenditure on IT is less than a quarter of the industry average.

A collaborative ethos

All of this is built on a strong culture of collaboration, which analysts attribute to helping the retailer become one of the few beneficiaries of the ongoing, rapid channel shift to online from store-based apparel. This is helped by a lack of hierarchy. Formal job titles are avoided, while Zara consciously hires candidates who can work in a team and links individual bonuses to team success. At Zara HQ, an open-plan environment makes it easy for teams to network with each other, something that is actively encouraged.

Questions to ask yourself

Here are some questions to help you take stock before moving on. As ever, please make some notes for future reference.

- How comfortable are you trusting others to make decisions?

- How can you increase this level of comfort?

- What decisions can only you and your leadership team make?

- What decisions can you therefore delegate to others?

Connected leader’s checklist

- Devolving decisions closer to the customer increases your business’s ability to deliver a great customer experience and its overall agility.

- Doing so with a clear freedom framework in place gives you confidence that people understand the mission you are all seeking to achieve and the values that define how you want to achieve it.

- You need to create a culture where your colleagues feel confident and competent to take decisions. By giving them the process, information and coaching support you can enable them to make those decisions well.

Notes

1 The Business Directory, www.businessdictionary.com/definition/empowerment.html (accessed 17 June 2015).

2 Office of Rail Regulation (2013) ‘Final determination of Network Rail’s outputs and funding for 2014–19’, http://orr.gov.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/452/pr13-final-determination.pdf (accessed 11 September 2014).

3 Spreitzer, G. M. (2008) ‘Taking stock: a review of more than twenty years of research on empowerment at work’, Handbook of Organizational Behaviour, London: Sage, pp. 54–72.

4 George, B. (2003) Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the secrets to creating lasting value, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

5 Leithwood, K. and Mascall, B. (2008) ‘Collective leadership effects on student achievement’, Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 529–561.

6 Uhl-Bien, M. R. and Marion, R. (2011) ‘Complexity leadership theory’, in Bryman, A., Collinson, D., Grint, K., Jackson, B. and Uhl-Bien, M. (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Leadership, London: Sage.

7 Robertson-Smith, G. and Markwick, C. (2009) ‘Employee engagement: a review of current thinking’, Institute for Employment Studies, www.mas.org.uk/uploads/articles/Staff%20-engagement-current-thinking.pdf (accessed 11 September 2014).

8 Towers Watson (2008) ‘Global Workforce Study 2007–2008: Closing the engagement gap: a road map for driving superior business performance’, London: Towers Watson.

9 MacLeod, D. and Clarke, N. (2009) ‘Engaging for success: enhancing performance through employee engagement’, A report to government; http://www.engageforsuccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/file52215.pdf. London: Office of Public Sector Information.

10 Mintzberg, H. (2009) ‘The design school: reconsidering the basic premises of strategic management’, Strategic Management Journal, 11(3), 171–195.

11 Daum, K. (2013) ‘8 tips for empowering employees’, Inc, www.inc.com.

12 Blenko, M. W., Mankins, M. C. and Rogers, P. (2010) ‘The decision-driven organization’, Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 54–62.

13 Hugo, V. (1982) Les Misérables, London: Penguin Classics, Reprint.