Situation and Character Driven Stories

“Comedy and fantasy are the two most difficult things in the world to do, because your audience is not educated exactly to what, for example, a rabbit six feet high will do. You have to make him believable to yourself.…That’s the basic business of the whole matter.”

—Chuck Jones

There are two basic types of character animation films: situational film and character-driven film. In a character-driven film, the story works out of the character’s personality. For example, a rabbit innocently occupies a rabbit hole on the exact spot where a prospector wishes to dig for gold. The prospector attacks the rabbit.

If I rename the rabbit hero of this story “Bugs Bunny,” we instantly know how the plot will develop. Bugs’ code of honor allows him to take justified revenge on the prospector since he has been attacked. The story develops out of Bugs’ personality. An unknown rabbit might react differently and there would be no guidelines as there are with an established character.

A classic story formula goes something like this: “Act One: Get your hero up a tree. Act Two: Throw rocks at him. Act Three: Get him down out of the tree.”

Stories based on “situation” often put ordinary characters in extraordinary predicaments.

[Fig. 4-1] An unknown character needs to establish its “rules of engagement” with its adversaries, while a familiar character may react in a familiar way.

In Gene Deitch’s adaptation of Jules Feiffer’s MUNRO, the titular hero is a normal four-year-old boy who is drafted into the American army through a bureaucratic oversight. The little boy “gets up a tree” when he is placed in an adult situation. The “rocks” in the story come when Munro’s attempts to tell the truth about his age are ignored by the military brass. His confessions are considered unmanly. The adults refuse to see that he is just a boy. Munro attempts to adapt but only “gets down from the tree” when he throws a tantrum and his childishness becomes obvious to everyone. At the end of the story Munro is once again a normal, unremarkable four-year-old boy.

Messages can be conveyed in an entertaining fashion by appealing characters. MUNRO used humor to contrast the child’s mature behavior with the military characters’ immature minds. War is likened to a children’s game. The message—war is absurd; the ‘cause’ the army fights for is childish—could easily have become formulaic and didactic if stated more obviously.

Stories become interesting when the heroes use their virtues and skills to overcome obstacles and character flaws and reach a clearly defined goal. This does not mean that you need a violent conflict, or even a villain, to make a story work.

A character’s conflict can be within himself, or against nature—perhaps a stubborn weed is growing in the flower bed. There are no dull stories. There are only stories that aren’t well told. You can MAKE something interesting. It’s your job.

Characters that react off one another and show us an unfamiliar view of this or another world can be quite as interesting as characters who fight one another. Conflict in a story does NOT mean violence or fighting. It can be something as simple as waiting for a kettle to boil.

The hero is affected by his or her experience. At the end of the story the hero will have undergone a change of habit, personality, or even physical appearance (think of Cinderella’s magical transformation). The process of change, also known as a character arc, brings animated characters to life. The character arc is roughly similar to the story arc which will be discussed later in this book. Both arcs start on one level and develop through conflict to end on a higher plane than the one on which they started.

The Ugly Duckling literally changes into a new character. Many animated characters go through a physical and emotional transformation during the course of their stories. But Munro remains the same small boy at the end of his army adventure because MUNRO is really a story about foolish bureaucracy. The titular character is only a catalyst that precipitates the action.

Clichéd characters never create the illusion of life since their personalities and actions are completely predictable.

[Fig. 4-2] Simplistic story formulas with stock or formulaic characters lead to predictable conclusions.

Stock heroes may overcome some obvious personal weakness or external obstacle By Working Together or Going on a Journey or By Just Being Themselves instead of thinking for themselves. All their problems are resolved by the fadeout because the stock story formula guarantees a happy ending. The audience knows exactly what to expect.

[Fig. 4-3] A Stock Story. Pick one letter from each category. “I must find the (a) ring, (b)Princess, (c) kingdom, (d) golden fleece, and rescue the (a) Princess, (b) ring, (c) golden fleece, (d) kingdom, to win the (a) kingdom, (b) golden fleece, (c) Princess, (d) ring, but first must overcome my (a) enemy, (b) lack of self-esteem, (c) father, or (d) all of the above.”

Formulaic plotting without real conflict or character development produces dull and predictable stories. This is where your personal experience comes in. An appealing character with human virtues and failings will create more interest than a standard- issue character type that has appeared in many other animated films. Unusual characters will solve problems in an unusual way, so that even when the story is “stock,” the interpretation is not.

[Fig. 4-4] A hero’s goal must be clearly defined at the start. Illustration from SON OF FASTER CHEAPER, reproduced by permission of Floyd Norman.

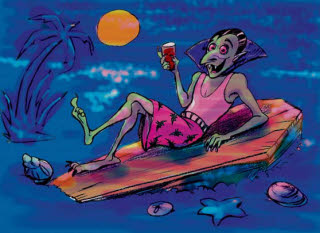

[Fig. 4-5] Count Dracula Goes to Bermuda. Pass the moon block!

Movie or comic-inspired vampires, monsters, and mad doctors can easily become clichéd. Consider placing them in unfamiliar locations and varying their costumes and props accordingly, as shown in Figure 4-5. This approach can create new stories with old characters.

Stop If You’ve Heard This One

A man falls into his computer/television set and finds himself in a new world. A woman turns out to be a vampire and bites her date’s neck. A man dies and his possessions are packed in a box. A hunter’s prey catches the hunter instead. A man cannot distinguish between dreams and reality.

These situations have been used in hundreds of films. They are not stories, but gimmicks. Gimmicky films impose their stories on the characters. There are no character arcs; only interchangeable puppets moving toward the foregone conclusion of a cardboard ballet.

Gimmicks like the ones listed above should be avoided when constructing stories for animated films—unless you can make them seem new and different from all the other versions of the story or character.

Why did the preview audience for SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS cry when the princess died? The ending of the story was well known at the time. SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS created characters with believable personalities and desires that aroused audience sympathy so that cartoon drawings were seen as living beings. The Dwarfs in the original Grimm Brothers story were nameless ‘little men’. In the film, each Dwarf is a distinct character that represents one aspect of a human personality. Snow White’s interaction with the Dwarfs and animals adds depth to her character and makes us care about what happens to her. Snow White’s relationship with the Dwarfs is that of a mother to little children. The Dwarfs are both adult and childish, with recognizable human flaws and virtues. But the Wicked Queen is a one-dimensional villain with no redeeming qualities. Her hatred of Snow White is the conflict that motivates the story.

A fairy-tale story’s ending is predictable—they all live happily ever after—but the journey need not be. A well-paced story with sympathetic characters will hold our attention even when we already know the ending. So if you can find a new twist on gimmicky situations such as the ones listed at the beginning of this section, by all means try it. Develop the characters and don’t construct story-by-numbers. Strong characters will make an old and familiar story new and interesting.

Defining Conflict

Many classic animated films are based on simple conflicts. An internal or external obstacle must be overcome. The stories of CINDERELLA, SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS, and SLEEPING BEAUTY all contain conflicts between the heroine of each story and jealous characters who wish to displace or kill her. This conflict may be described as: ‘I want something that you have.’

Some characters are victims of circumstance. DUMBO must save his mother from jail and be accepted in the circus world. PINOCCHIO, an innocent led astray, must rescue his father from the whale by his own initiative. Beauty must rescue her father and also save Beast’s life. Nemo’s father must find his son who is lost somewhere in the Pacific Ocean. These conflicts are life-or-death situations. The characters ‘must do it.’

Simba in THE LION KING must overcome his character weakness and accept his responsibilities. This conflict may be described as ‘I don’t want to do it.’ Characters may prevail despite early setbacks. (This is a common device in animation storytelling.) They ‘will do it.’

Good characters make these simple conflicts interesting. It has been said that there are only a certain set number of basic plots in literature. If your characters are appealing and believable you will avoid the been-there-done-that feeling that comes when stock characters are placed in predictable situations.

Exercise: Design and thumbnail two characters illustrating the following conflicts. You may use several sketches per example and include props.

- I can’t do it.

- I must do it.

- I want something that you have.

An example is shown in Figure 4-6. This elementary conflict creates the germ of a story.

[Fig. 4-6] I don’t want to do it. Which character displays the conflict?

Log Lines

A brief description distills the essence of the story and makes a concept easy to understand. This description is sometimes called a log line. Here are some hypothetical log lines from animated features:

- Surface appearance can be deceptive. People come in layers, like onions. —SHREK

- A freak turns his defect into an asset, redeeming himself and his mother. —DUMBO

- Magic comes from personal initiative and the working of conscience. —PINOCCHIO

- A callow youth learns to accept his responsibilities. —THE LION KING

- There is some good in every character. —LILO & STITCH

Short films can also have log lines:

- A large opponent menaces a peace-loving rabbit, who takes appropriate revenge. —nearly every Bugs Bunny cartoon ever made

- One sister wants the other sister dead. —ANNA AND BELLA (this is the actual log line for Børge Ring’s film)

- A bulldog wishes to adopt a small kitten but his owner won’t let him bring any more things into the house. —FEED THE KITTY (Chuck Jones)

- An eccentric inventor’s dog is much cleverer than he is. —all of Nick Park’s Wallace and Gromit films

Write a few brief sentences describing your basic story ideas and characters. You will have time to elaborate the gags and plot twists later. Create several log lines and thumbnail the more interesting ones. The sky is the limit at this point—this is why this phase of development is called ‘blue sky’. Work with ideas that interest and intrigue you—don’t create stories that you think a studio or audience expects to see. The best animation is made by artists who project their enthusiasm and spontaneity into their work.

The story should be told by the most interesting characters. Secondary characters are often used to help tell the hero’s story. We often identify more with them than we do with the hero. For example, the rather ordinary Doctor Watson writes about the adventures of his extraordinary and unpredictable friend Mr. Sherlock Holmes. We see a great part of Snow White’s story through the eyes of the Seven Dwarfs and the forest animals in the animated SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS. These likable characters find her appealing, so we do too. We do not learn about the Seven Dwarfs’ background since this material is not relevant to Snow White’s story.

Subplots that distract from the main story idea should be avoided, or the film will break up into a series of disconnected threads. All subplots and secondary characters must support the main story. If the sidekick is more interesting than the hero, maybe you are telling the wrong character’s story!

Heroes should have recognizable goals to achieve, obstacles to overcome, and a few flaws that make them imperfect and therefore interesting to us. If your hero easily solves every problem and never makes a mistake, they will never encounter conflict. There will be no surprise or suspense in their story since the outcome will be a foregone conclusion. Your hero will become a bore and secondary characters that do have obstacles to overcome will easily distract us from the main story.

There should be a piece of Kryptonite for every Superman.

[Fig. 4-7] Secondary characters may become more interesting than “perfect” heroes.

[Fig. 4-8] Disco Fever! Nothing dates faster than ‘hipness’ and ‘edginess’.

Animated characters often use catch phrases from popular culture to get a laugh. The Warner Brothers Studio’s cartoons immortalized many phrases that originated on radio shows.

Pop culture references can become a cliché that dates the film to a specific time.

Topical references should be avoided unless they help advance the story, and even then, the story should not depend on them. Most topical jokes need to be explained to anyone born after the date the film was released. Some work without explanation. The Genie’s caricature transformations in ALADDIN’S “A Friend Like Me” song are funny even though most five-year-olds did not know who William F. Buckley or Ed Sullivan was when the film was originally released. The story point reads well regardless. The comedy comes from the Genie’s quick-change artistry and the wildly different speech patterns and movements of the caricatures. It is easy to understand that the Genie is transforming into different people and the cultural references are a bonus joke. The quick changes are a feature of the Genie’s personality and are not simply a gimmick.

Good animation is perennial: if the stories and characters are appealing enough, they will connect with their audience long after contemporary references in the film are forgotten.

Parodies and Pastiches

Parodies are mockeries of preexisting material. They will use the same plot elements and characters as the original staged as farce. Figure 4-9 shows a new staging of Romeo and Juliet. The characters may be taking themselves seriously, but their ludicrous appearance and the falling balcony makes the scene comic. Parodies may or may not be affectionate, but you must be familiar with the original material to accurately mock it.

Parodies tend to work best in short formats. If the raucous mood continues for too long a time the mocking tone can become wearying. Parodying another movie or story essentially allows someone else to write the story for you. Your film is a reflection of another work and its success will depend on whether audiences are familiar with the original material.

A pastiche takes the elements of the source’s style and affectionately reworks the material into something new. It can contain parody but it is a distillation of a genre. Chuck Jones directed a brilliant series of pastiche cartoons including WHAT’S OPERA DOC? which distilled the 16-hour Wagnerian Ring cycle into a six-minute cartoon. SHREK’s leads were characters from classic fairy tales, except that the roles were changed and fairy-tale clichés were turned on their heads—the “bad ogre” was the hero, the “beautiful princess” was the monster, and the “noble king” was the villain. Pastiches allow you to create original characters that have more depth and personality than a story that parodies a specific role or film.

When targeting a genre rather than a specific film, the animator takes cultural references that are familiar to the audience and reinterprets them to create something new. It’s not what you do—it really is how you do it.

[Fig. 4-9] A parody uses absurd characters and overthe-top interpretations to affectionately or sarcastically mock its source material.