Show and Tell: Presenting Your Storyboards

“You have to get the story point across in the first ten seconds of a pitch.”

—Ollie Johnston (to author)

The day for the story pitch has arrived. Sometimes, it’s the day after you get the handout! Your first consideration will always be ‘readability’ whether you have had one day or a month to finish your assignment. The boards are the most important part of the pitch but the quality of your presentation is nearly as important. A bad presentation will hurt a good storyboard. You’re providing the acting and the timing for the action, so your commentary is 50 percent of the pitch and has to communicate as clearly as the boards do.

Your objective is to convey the story point clearly to the audience, in real time. Be prepared. Number your panels so that they do not get out of order. Be sure to pin the panels correctly beforehand. You won’t have an opportunity to change the order during the pitch.

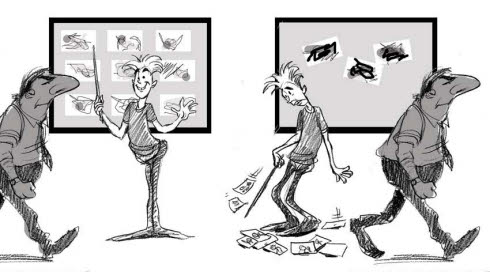

[Fig. 18-1] Number the storyboard drawings so that you are able to reassemble them in the correct order should a few fall off the boards. Drawing from Son of Faster Cheaper by Floyd Norman, reproduced by permission of Floyd Norman.

Memorize the dialogue and the action in each panel. It is not good to stand and read dialogue off the small cards that are pinned under the panels. It’s even worse if you forget it completely and freeze up or “die” in the middle of your pitch. Say the same dialogue that you have on the boards. Use one sentence to describe the action in each panel. If your panel shows Sherlock Holmes bursting through Watson’s bedroom doorway, it’s enough to state, “Holmes bursts the door open—Wham! Pit-pat-pit-pat,” and let the drawing do the rest.

Do not use extraneous material. Stick to the story. Anecdotes, useless ‘factoids’, back story, and other stuff that doesn’t matter will only slow down the pitch and bore or confuse your audience. Use simple descriptions of camera moves; don’t give them a technical lecture.

[Fig. 18-2] Know the action in each board and memorize the dialogue before the pitch. Be completely familiar with the material. Drawing from Son of Faster Cheaper by Floyd Norman, reproduced by permission of Floyd Norman.

Make a joyful noise. You should provide appropriate noises and sound effects where necessary. If you cannot reproduce the exact sound of a planet imploding, simply say “Bang!” Sound effects can add a lot to the presentation so it helps to be a bit of a hambone. Don’t be nervous and don’t worry about looking a little ridiculous—the audience should be concentrating on the boards. You are literally just a background noise.

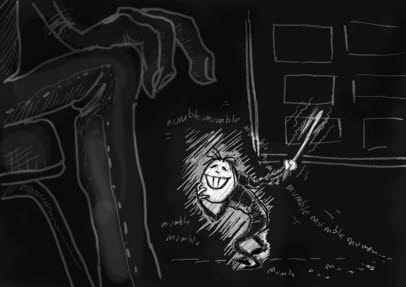

[Fig. 18-3] Provide any necessary sound effects with your own voice. Don’t go overboard, but use whatever works in the context of the storyboard.

If your boards illustrate a musical composition, you can have it playing in the background while you offer a description of the action or simply play the music without commentary while you point to each panel of the boards. Don’t be completely dependent on having the musical accompaniment during the pitch.

I’ve seen a story man recite his entire pitch with the aid of a puppet. Another one unrolled a ball of string around the story room and rewound it to a different knot as he made each point of his pitch. If you feel comfortable using additional materials and feel that it will help your pitch, use them—as long as they do not completely upstage your boards and your story.

Rehearse the pitch. Pitch the boards for other storyboard artists, for animators, for your mother, for total strangers, to be sure that everything reads well. You’re too close to the thing to be able to judge it objectively, so a second or third opinion becomes necessary. I’ve received some excellent story suggestions from non-animators. After all, the ultimate audience for the project is ordinary people who are interested in hearing

a story, not animation professionals. Rework and revise any inconsistencies or omissions before you go up before a highly critical professional audience. Be sure that all story points are reading clearly. You will probably change your boards more than once while rehearsing them. It’s impossible to predict how directors and producers will react before you actually present the materials. If you are working with a StoryHead, they will have signed off on the boards before you pitch. If you are working alone, trying the boards out on an auditor who is not familiar with the material will help ensure that they read well to someone other than you. You will, with practice, be able to make your pitch easily and coherently.

[Fig. 18-4] Rehearse your pitch with the help of someone else. Be sure they are able to give you feedback so that you know when something isn’t working as well as it should.

Show enthusiasm for the material. If you don’t think it is good, why should anyone else? Good story people are excellent actors. They keep the audience’s attention focused on the story from the first frame to the last. Make the pitch entertaining enough to hold the audience’s interest. Avoid ironic commentary on the artwork. Never make disparaging comments such as, “This isn’t any good,” or “I meant to do this instead of that.” Never apologize and never tear down your own work—that’s the director’s job.

[Fig. 18-5] Believe in your story. Don’t point out weak spots in your own boards.

Your panels should be pinned to large storyboards that are mounted on the wall or they may be pinned directly on the wall if the surface is suitable. They should not be displayed on a tabletop or handed around like playing cards (I’ve seen both). The storyboards should be a neutral color. Black, gray, cork, or off-white are common. Pin the drawings separately from the dialogue panels, since they may be rearranged. Get a simple pointer. A yardstick will do. Don’t use your hands. Stand with your back to the board, a little to one side. Always face your audience. Make eye contact with them while doing the pitch. Never obscure the board by standing in front of it and never turn your back on the viewers. Your pointer will enable you to reach across the boards to pitch more distant panels without doing this.

[Fig. 18-6] A pointer will enable you to pitch the boards without turning your back on the audience. Be sure that the boards are never obscured.

If you feel comfortable doing character voices, by all means do them. Story men will play women and story women will play men if they feel it will help the pitch. If you do not wish to do this, simply pitch the boards using your normal voice. Your inflection should help convey the action in the drawings. Don’t mumble and don’t read in a monotone. Speak clearly and loudly enough for the audience to hear you but not so loudly that you’re audible next door. Keep a positive attitude. Smile. Act like you’re enjoying yourself.

I have seen instances where story men and women got ‘into character’ with costume as well as voice talent. I was once only allowed to pitch my designs while wearing a huge felt highcocked hat that I’d purchased as reference for the creature’s costume! Use your judgment. Neat clothing is perfectly suitable for a story pitch.

[Fig. 18-7] You may want to do character voices for the different parts. Sometimes the character projection doesn’t end there!

Introduce yourself and your sequence at the beginning of the pitch. A brief introduction will allow you to connect with the audience. If your sequence is part of a larger film it is good to let them know what comes just before your bit. Give them enough material so that they see how the sequence works in context, but don’t try to tell the entire story. Ollie Johnston told me that the main story point had to be apparent to the audience in ten seconds or less. If you are pitching beat boards, state your log line first (the single sentence that sums up the meaning of the story as described in Chapter 4). The drawings and your brief commentary should be able to get the point across.

If you have character design sketches, pin these up on a separate board. It can help if you introduce the characters before beginning your pitch, especially if this is your first pass on the boards. Be sure to write the characters’ names on all drawings.

It is polite to point. Don’t smack the pointer up against the story panels. You are not mad at them—at least not yet—so don’t work out your frustrations or nerves in this fashion. The noise will distract your audience from what is on the boards. Point to each panel in turn and hold the pointer steady on the panel while you say the dialogue and describe the action. Then slide the pointer to the next storyboard. Bouncing the pointer up and down on the panels is distracting and very counterproductive.

[Fig. 18-8] Don’t beat around, or on, the storyboard.

Work in real time. You are giving your auditors a foretaste of what the finished film will be like. You will have to read brief explanations of some of the action occasionally since the film is not animated yet, but be sure to keep them brief. If you have to describe the action at length, chances are you did not draw enough storyboards to get the point over in the first place. It is better to speak too long than not long enough. Just be sure your audience is not nodding off (I’ve seen this happen during a dull presentation). Don’t be pretentious. Keep your story points simple. Do not give convoluted explanations of the action and lengthy biographies of your characters. All that matters during the pitch is what is on the storyboard. If your story does not work, all the explanations in the world won’t help you.

[Fig. 18-9] Don’t drag things out. If you’re talking too much, you probably did not draw enough panels to convey the story. Your audience can, and will, lose interest.

Don’t rush. Take the necessary time to get the story point across. Don’t run words together trying to cram a lot of information into a short timeframe. Be sure to pace the story pitch. Speak in sentences, not paragraphs. Let the drawings carry half of the presentation.

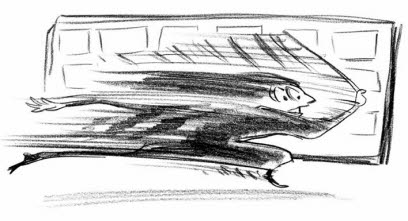

[Fig. 18-10] Don’t rush through at high speed.

Director Jack Kinney wrote of a story man who got so ‘into’ his performance that he actually ran out the door while describing the character performing this action on his storyboard (The other artists locked the door behind him and went to lunch. They sensed that he was a showoff and reacted accordingly). Act, but don’t overact. You will distract attention from the storyboard and you won’t impress your audience.

[Fig. 18-11] Don’t overdo things.

After your pitch, you’ll get down to the real work—turning over the boards and revising them!

The More Things Change: The Turnover Session

Story people learn to welcome change. A turnover session is where you find out just how much change you and your boards can take. All storyboards are changed at least once. Never take these changes personally. Your only consideration should be that the story read in the clearest possible way.

Turnover sessions happen immediately after the pitch. The audience, which may consist of other story men and women, animators, the directors, and the art director, will make suggestions for additional action, revised staging, or new lines of dialogue. These suggestions, no matter how bizarre, are pinned up on an additional storyboard. If the directors like the changes, or do not like one of the existing panels, one or more panels of your board will be turned over. The deleted board(s) will be pinned so that their blank backs face the viewers, and the new drawing(s) will be pinned up on top of them. Sometimes the suggestions are drawn on new storyboards by the crew, but ordinary self-stick notes will often be used as well. The sketches will be very rough. If the changes are approved you will incorporate them into your reworked boards prior to the second pass, or pitch.

You may be asked to insert close-ups for a reaction shot or place your camera farther back to get more of the action into the frame. Someone may suggest an entirely new piece of acting or business that will lengthen the sequence. On occasion you will be told to flop a scene. This is not an indication of failure. Flopping a board means that the action will be staged as a mirror image. Sometimes entire sequences have their boards flopped. The advent of computers has made this a lot easier for the story people to do. In the old days, they just had to draw everything going the other way. Now, boards can be scanned and reversed automatically.

Plan to make at least two pitches for your boards. That is, if you are lucky. Some directors might make a few small changes or tweaks and get the boards up on reels, or shot and timed to a soundtrack in a story reel, before making a final decision on the staging. The boards might be sent back to you at a later date for reworking if the story changes. At the Walt Disney Studio, the boards were pitched “until they got it right or until they ran out of money,” according to story man Floyd Norman. Constructive suggestions from your colleagues and friends will help foster a team feeling and make your boards stronger.

[Fig. 18-12] An unsuccessful turnover session. Most won’t be as dismissive as this, but some panels always wind up on the story room floor.

The BBC reported that 3,000 adults who took a survey of most-feared incidents rated public speaking higher than financial ruin and death itself. If you prepare your pitch properly, you should acquit yourself well speaking in public and avoid the other two problems.

[Fig. 18-13] Pitching a storyboard is rather like public speaking, but it need not be a dreaded occasion.

“Dying is easy. Comedy is hard!”

—attributed to Edmund Kean