3 Project Development (a.k.a. Preproduction)

Having a Clear Goal

Many things in this world are universal. Most successful companies have a strong and clear business plan, most great Hollywood scripts start as well-plotted outlines, and almost all great shoots begin with a clear goal.

The concept is simple: know what you’re going to shoot — or at least what you hope to shoot — before leaving the office or house. I find that although storyboards and scripts may be overkill for many simple shoots, a shot list in outline form of what I intend to capture usually makes a significant difference. Once you arrive at your location and begin shooting, whether it’s a full-blown action-sports commercial or just shooting a contest for fun, it’s very easy to eventually get caught up in the moment and miss, or forget, to capture a key shot.

To avoid missing shots, take a few simple steps. First off, for large events, bring a list of athletes you plan to cover. Then, as you go through the list, simply check off the names with two marks throughout the day: one mark for B roll of them riding, and one mark for a sound bite or lifestyle shot. In the event of commercials and scripted shoots, always keep a shot list in your back pocket, and constantly review it to make sure you’re not only getting everything, but that you’re also shooting things in the most efficient order. This may all sound like overkill if you’re just making a skate video, but nothing’s more frustrating than getting into the edit bay and realizing you don’t have a close-up shot of your main athlete’s face.

There’s no production like preproduction. Every great project will begin in prep. Like the old days of shooting film prior to video, the more prepared you are going into your gig, the better off you’ll be, and the better it will be. After all, the ultimate goal of most action-sports filmmakers is to produce a piece that is both compelling and entertaining to your audience.

Illustration 3-1 Finding funding: Don’t movies cost millions of dollars to make?

Okay, it’s true most movies can cost hundreds of thousands — or even millions — of dollars to make. But in the words of Steve Martin in Bowfinger: “That’s after gross net deduction profit percentage deferment 10 percent of the nut. Cash, every movie costs $2,184.”

There are several types of financing available for your project, but they all follow one basic guideline: willingness to finance is directly proportionate to how many viewers you will get. Think of your work as a commercial; the more eyeballs you get, the more valuable it is. Therefore, if you know you’ll be featuring top-name athletes or have a compelling untold story, it’ll be easier to get someone to give you money. Investors expect to make their money back on a project, so when you pitch it, take an angle of how popular your film will be and why. Show a potential investor how similar projects in the past have done, and what will make your project unique (read more on this in , Distribution). Below are the basic financing options you’ll encounter. For additional material, check out books such as Filmmakers and Financing by Louise Levison.

From government grants and tax incentives to debt financing and self-financing, you’ll find that with a little research, there are real-world options to get your project paid for. Many state governments and even the federal government offer tax breaks and grants for certain types of films. However, there is always a limited amount of money allotted each year, so it’s crucial to submit your project before that funding runs out.

The biggest obstacle to finding government funding through grants or taxes will be meeting the requirements they impose. If you plan to document a great athlete who was raised in Pennsylvania, for example, then you might be able to promote the beauty of the countryside in your film. This, in turn, can bring employment and tourism to Pennsylvania, and thus make it easier to get state funding for your project. The rules are different for every region, so read up online first, and then try your local film commission for more details.

The next option is debt financing. This can be the hardest for a small project because it involves selling the rights to distribute your work before you even make it. Similar to government financing, this option relies solely on the expected draw of your project. If, for example, you plan to feature five top-name athletes in your film, and the most recent video they were in sold 50,000 copies each, then you may be able to presell your project to distributors based on the estimated profit they think they will make. I recently had lunch with an up-and-coming director of independent films. Her project was coming up short on financing. She needed $3 million to make her movie, but the distributors were offering only $2.5 million for the project with the current actors attached. The result was that she now had to either cut out key elements of the film, which would hurt it in the long run, or replace her cast with a new actor who was “worth” more to the distributors/financiers. In Hollywood, this is a typical example of how debt financing can work.

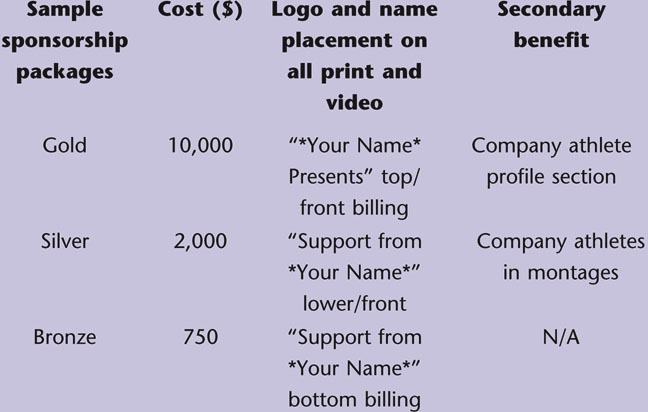

Another option for action-sports videos is to sell off sponsorship rights to help get your film made. Sponsorship deals will usually be sent out with various options — for example, a gold, silver, or bronze package, each one involving a different level of financial or material commitment to related companies (see Table 3-1). Just like debt financing, if you are certain your film will get many viewers, then the advertising value is great to these potential sponsors, and getting them to help pay for your production is very possible.

Table 3-1

One of the first skate videos I ever made was pieced together with deals like this. I wasn’t able to get many companies to give me cash for the video, probably because it was my first, but they were willing to pay all my expenses to travel with their teams and document them on the road. I spent weeks overseas shooting the athletes on the sponsors’ dime, in exchange for gold sponsorship packages on my video. The result was a very international feel with enormous talent in the video and very little overhead for me. Additionally, using the leverage I now had of guaranteeing the grand scope of the video, I worked in several promotional deals. One was with the then-booming Soap grind shoes. The company gave me 1,000 free sneaker vouchers to slip into the videos. In our ads, we promoted the chance to get the free shoes. I also traded ad space with several magazines, offering them a commercial in our video in exchange for a small ad in their magazine. When all was said and done, the project cost me very little beyond my time and energy, and ended up doing fairly well. Of course, I was just happy to have gotten my first video made.

Classify Your Project

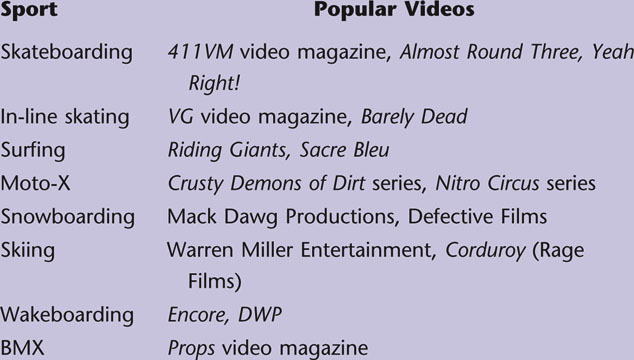

To begin with, let’s separate the types of projects into four main categories: documentary, commercial, short subject, and feature length. The most popular is the documentary, and will include the average 30- to 45-minute skate or other action-sports video, as well as the true-to-form introspective interview-driven documentary. These videos exist in a wide range of sports, as seen in Table 3-2.

Table 3-2

Short-subject videos are becoming more popular every day with the proliferation of the Internet and such sites as YouTube.com, MySpace.com, PureVideo.com, and now countless other sites that are not only sharing content but also profits with the project producers. One of the original profit-sharing sites, Metacafe.com, paid out well over $25,000 to a video producer for his clips of gymnastics stunt routines. These sites represent the first step toward the future of entertainment, and quite literally the changing era of the old distribution model.

It’s always important to classify your project clearly and to know your end goal so you can best shape and mold it to the right audience. If your intention is to make a documentary on one popular action sport, then research what else is out there, and watch some of the most popular videos to get a better feel for what has worked in the past. Many ideas in these industries have been done, and then repeated, because content producers didn’t do their homework and check out prior works. As a former athlete myself, I can think of countless times when various film and TV producers, as well as documentarians and inventors, approached my friends and me with pitches and concepts that all started out the same: “We’re gonna do this amazing thing — it’s never been done.” Of course, it already had been done. Keeping all this in mind, just go with your gut at the end of the day. If you think something similar to your project has been done, but you’re really passionate about it, then perhaps it’s still worth pursuing.

Passion … and Why You Need to Have It

If life is about passion, and work is about money, then what happens when you love what you do for a living?

It was 1999, and I was standing on top of a vert ramp somewhere outside of Los Angeles, filming the finals of a pro skate contest for ASA Entertainment. The weather was perfect, the skating was going off, and I was flying back and forth on the deck, shooting trick after trick, so excited and into it that I didn’t notice or care who was watching me. As the contest wound down, another cameraman approached and said that someone in the crowd wanted to speak with me. I headed down the ramp, a little unsure of what to expect. The woman I met told me that she was an executive assistant at Warner Bros., and explained that my passion and excitement for what I was doing made it more entertaining to watch me than the competition. She handed me her office number on a napkin and said to stay in touch. Her name was CJ, and sure enough, she became a great friend and personal contact, getting my action-sports shooting and directing reel into the hands of several project-development executives who ended up meeting with me. She was one of the true blessings in my early years in Los Angeles.

Figure 3-1 C-17 shoot at 8,000 feet for USAF DoSomethingAmazing.com.

Figure 3-2 Neal Hendrix, fakie hurricane, shot from the deck at Camp Woodward.

Photo by Bart Jones.

The lesson learned here is that passion can be far more powerful than any other motivator. Nobody wants to get involved with a project whose founder doesn’t even believe in it. If you pursue what you love, and ultimately do what you love, eventually you will find success, and the money for doing it will come as a by-product. Just keep your focus, keep yourself motivated, and keep your passion.

Choosing Talent and Getting a Release

Talent can be defined in many ways. Although it is most commonly used to describe ability levels, in the production world, the “talent” is simply the people you intend to shoot. If you are documenting a skate contest, then your talent is probably the competitors. If you’re shooting a home movie, then your talent might be your friends or family. It all starts with the talent, and it’s important to decide who best fits your project. Many great movies have horrible scripts or even terrible directing, but if you put the right cast in a story it always seems to work out. Take Johnny Depp, for example — the guy can’t seem to make a bad movie.

Once you know the talent you will shoot, getting all the necessary releases is your next important step. If you plan to shoot a live event that’s already been scheduled, you’ll have to contact the event producers in advance and ask if you need a media badge or pass. Most events ask all athletes to sign waivers that include their photographic release. In this case, if the event organizer is okay with your being there shooting, then you may not need any further release from the talent. I strongly recommend that you review the release if you plan to distribute your project. Although most events do blanket all media for all uses as a way to get exposure for themselves, the last thing you want is to get a “cease and desist” in the mail for a video you spent a year creating.

Releases can be tricky as well. I’ve shot hundreds of events. Many times, athletes are happy to sign additional releases, so long as they understand how you plan to use the footage. The problem arises when you get your own release for an athlete, but you’re shooting at some company’s event. For example, the X Games try to maintain a healthy degree of control over their actual competition footage. I recently included some X Games shots, which I had done for them, on my camera work reel. I had posted my reel for some coworkers to see on YouTube, and the content got flagged and removed by ESPN. This is a bizarre example, considering that the footage was my own footage, and ESPN had hired me to shoot it — but it represents just how important getting proper clearance can be when you’re dealing with a large company.

Figure 3-3 Vans Cup at Tahoe, 2007.

Courtesy Windowseat Pictures.

If you plan to shoot athletes outside of an event, you’ll usually have more time with them to prep. Being able to cruise into the city or to a local ramp will allow you to focus and work with them on what you need to get. From a release standpoint, you’ll likely want to take care of any documents you have in advance. Get the paperwork out of the way, and keep it simple and unobtrusive. The last thing you want is to hand an athlete a thick, intimidating document that they’re afraid to sign. Basic photographic and likeness releases can be found online, although you should talk to a lawyer about what you plan to do. I generally like to also include a paragraph that helps protect myself: a release of liability in case the athlete gets injured. A basic document can be as short as half a page, or as long as several pages.

Next, finding your talent can be difficult. If you have an idea for a project, you can always contact an athlete via the Internet by either finding their email address or discovering if they have a manager who represents them. There are a few companies that handle athlete management, and you might be able to work a deal to “package” a group of their clients for your project. Going through an agent or manager can be expensive and difficult, though. If you have any kind of connection through friends, that’s always the best way to go. Talking to an athlete via someone you know, or even directly with the person yourself, will save you a great deal of time and energy. Athlete representatives get paid to manage and look out for their clients’ careers; oftentimes they won’t be too interested in a project if it’s unpaid or a low-profile gig. That doesn’t mean the athlete won’t be interested, however; so if you can, always try asking them personally.

Insurance … Do you need it?

From shooting remote snowboarding in the Alps to capturing your buddies hitting handrails downtown, many projects happen without insurance. This is a sticky area, but there’s a good rule of thumb to follow: if you aren’t sure if you need it, ask a lawyer. Okay, so that was more of a disclaimer than a rule of thumb, but here are a few examples of what projects in the past have done.

Figure 3-4 A snowboarder spins the big kicker at Northstar at Tahoe.

Courtesy Windowseat Pictures.

First off, although insurance is crucial on many large productions, most action-sports home-video shoots happen without personal or production insurance. Being that most videos don’t have large budgets, and most of the athletes and filmmakers should have their own health insurance, it oftentimes just isn’t cost-effective to get a big-production insurance policy for a small video. Top action-sports videos are essentially documentaries, so the logic is that you are simply capturing athletes doing what they would have done anyway. Then again, this is America, and ever since McDonald’s was sued for the hot coffee that some woman spilled on herself, I’ve been a little wary of logic. If you know the people you are filming — and trust them as well — then it’s often a given that you don’t have to worry about your personal liability. However, if you are serious about documenting a group of athletes for your video project, then a liability release, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, can be a good start.

Production insurance can cover your equipment, which is always an asset. There’s nothing worse than shiny new gear getting destroyed because you got too close to the action. Once, while riding a motorcycle on an L.A. freeway, the wind pulled open a zipped backpack and sucked a microphone out of it.

If you have an apartment, a viable option is renter’s insurance with a rider for electronic equipment. The rider should cover a realistic portion of your gear when you are working away from home. This way, if your camera gets jacked, you’re covered. You can also opt for a credit card that has additional insurance options on products purchased with the card.

Illustration 3-2 Liability is always a concern.

If you’re shooting a larger production that is less documentary and more scripted or cast, then you can be liable for the talent and equipment you buy or rent. You should therefore consider a full insurance policy. Depending on the insurance company you choose, your deductible, and other variables, a normal $1 million policy can run anywhere from $100 to $2,000 a day. This is the type of policy that many rental houses will require if you want to rent high-end equipment such as film or full-HD cameras. A good source of information can be found on the web at sites such as the Independent Feature Project (www.IFP.org).

If you plan on shooting and producing your piece alone, then doing your liability-coverage homework could certainly cover you later. If you are shooting a larger project and plan to hire a crew, then your line producer should be able to research the best option for you. Although many commercials for television are still shot with large crews, most action-sports home videos, Internet commercials, webisodes, and documentaries are shot alone or with a select few professionals. A person who produces and edits nowadays is sometimes referred to as a “predator.” This means you’re covering almost all aspects of the production alone, and if it’s not scripted, then the producer is the closest thing to a director on the project.

Figure 3-5 Shooting/producing/editing — the action-sports championships trixionary.

Editors Make the Best Directors

There’s an old saying that editors make the best directors. This is true not only for making the best directors, but also the best cameramen or producers. It’s important for two reasons. First of all, as an editor, you get to see a wide range of work by various cameramen and directors. You can learn from their mistakes, be influenced by their style — and perhaps most importantly, get an overall sample of what has come before you. I remember cutting a short film for a college friend once, and going through the footage over and over again, looking for an insert shot to cut between two different takes from the same scene. Although it probably would have taken only a few minutes to shoot an insert, it never happened on the day,1 and now his film was limited by what we actually had to work with.

You’ll gain a lot from watching raw footage. People often ask how they can get better at shooting. In reply, the first question I ask them is if they really sit down and watch what they shot. To improve your shooting, the fastest way is to constantly review and critique your own footage. Sit in the edit bay and watch your work thoroughly. Think about what could have been better, what’s missing, and what you can do next time to make sure you notch it up a little.

The second reason editors make great cameramen and directors goes back to the Indiana Jones scenario as described in Chapter 2. Editors are able to see how rough and raw footage can start out versus how polished and refined it appears when it’s done. The process of cutting shots together, then adding visual effects, sound effects, music, and finally polishing it all can create a truly seamless piece that audiences will always get caught up in. So as an editor, you have the rare chance to truly see the potential and result of what was shot on the day.

As seen in the image in Figure 3-6, green screen can provide a very creative backdrop for taking a shot to another level. A great example of this can also be seen in the Girl and Chocolate skate company owner and legendary director Spike Jonze’s (Being John Malkovich) skate video Yeah Right! Shooting the pro-team riders performing countless tricks on all-green skateboard setups allowed Spike to remove the skateboards in post and create an insanely unique section for the video. A little work and planning in preproduction was all it took to come up with and prepare the video section for what it was, groundbreaking. So don’t be afraid to think outside the box. If you’re going for a widely accepted video, keep a strong eye on what’s accepted in the industry and what is perceived as cool — but beyond that, push the boundaries, get creative, and shoot what you are truly passionate about.

Figure 3-6 On the set with Windowseat Pictures for a Vans commercial.

Notes

1 “On the day” is a commonly used phrase to represent the period during which a shoot took place.