Portfolios of Projects

What’s different about Business Programme management?

Prerequisites for effective portfolio management

Directing a ‘portfolio’ of projects is a key senior management task, as it is this ‘bundle’ of projects that will take you from where you are now to your, hopefully, better future.

’What shall become of us without the barbarians? Those people were a kind of solution.’

CONSTANTINE CAVAFY, 1863–1933

The Business Programme

In Chapters 12 and 13 we considered the following definitions: A project, in a business environment, is:

- a piece of work with a beginning and end;

- undertaken within defined cost and time constraints;

- directed at achieving a stated business benefit.

Subprojects are tightly coupled and tightly aligned parts of a project.

Programmes are a tightly coupled and tightly aligned grouping of projects.

We also saw how a project moves from being ‘undefined’ to being ‘defined’. This was then put into the context of four project types:

- painting by numbers;

- going on a quest;

- making movies;

- walking in a fog.

Once this is understood, you should be able to define a single project in terms of its life cycle stages. However, business is rarely so simple that a single project or even programme can achieve all that is needed. The next step is to understand how bundles (or portfolios) of programmes and standalone projects are used together with other business activities to further your aims. We will call these ‘Business Programmes’.

Business Programmes comprise current benefit generating business activities together with a loosely coupled but tightly aligned portfolio of projects and programmes, aimed at realising the benefits of part of a busness plan or strategy.

They are best explained by using a simplified example.

You may have a business objective to increase your revenue from $10m to $15m in two years. You’ve chosen to do this by increasing your share of an under-exploited segment of your market. The alternative is to withdraw from that segment, milking whatever cash you can from it on the way. In order to achieve the required target revenue, you have found that you need to:

- Enhance your current product to include some new features. (Project 1 – enhance old product.)

- Develop a new product to exploit an unfulfilled need identified in the market. To do this quickly, you have decided to launch a basic version of the new product, as soon as practical, to start engaging the market. This would use existing manufacturing capability. (Project 2 – the basic new product.) The launch would be followed up four months later with an enhanced product which meets the full needs. (Project 2A – the enhanced new product.)

- Speed of delivery is a buying factor for your target market and current delivery channels are too slow. You need to decrease delivery time to protect revenues. If the speed of delivery can be greatly increased it will enhance revenues enabling you to win business off competitors. (Project 2B – decrease delivery time.)

- You also know there is a quality problem in manufacturing the current product. While the levels of faults have been acceptable to the target market in the past, this is not the case for the future. You need to reduce manufacturing faults and hence protect revenue. If faults stay at present levels, customers will choose alternative products. (Project 3 – reduce faults.)

You can see that the five projects are aligned to your overall strategy and that each provides a discrete business benefit. Most are independent. (Only Project 2A depends on Project 2 as you cannot enhance a product until you know what it is.)

Notice that the approach has been to split the new product development into two phases (Projects 2 and 2A). This benefits you by gaining early revenue and having a foothold in the market. Traditionally, organisations make their projects too big. Dividing projects into smaller pieces (chunks of change) makes success more likely and implementation easier.

Finally, you need to take account of the benefits you are expecting from the product as it currently is in the market. Your aim is to obtain a $15m revenue. The benefits from your current product and future projects and initiatives need to be sufficiently high to meet that target.

As a business manager, you are not particularly concerned with the individual performance of each project and product. Of more interest is the total benefit. Thus, if your current product starts to perform better than expected, a delay in a project may not be too significant. Only you can decide the relative importance of the projects within the business programme.

How did the projects within the business programme come about?

Keeping to the example, how did the managers derive their approach and end up with the five projects I described? The starting point was a problem for the directors of the organisation: they needed more revenue. They needed to look at their complete mix of products and markets and decide the most likely areas for gaining the additional, profitable revenue. (Perhaps they needed a new product and a new market!) One option identified by the review was that they either take a minimum prescribed market share of a particular segment or they withdraw from it completely. It was considered untenable to keep the status quo. This would lead to a decline in revenue to about $7m per year. This conversation is firmly within the domain of business strategy and planning. What is needed now is to take it to action.

The five projects could not, in fact, have come about directly as the result of a strategic review. The organisation simply would not have known enough to make that jump. At most, a required timescale and overall affordable budget annual cash flow could have been set (i.e. constraints applied by the business). However, a project could have been initiated to look at various options – a quest! The Initial Investigation Stage would spawn a set of possible projects. These may just have been:

- enhance the existing product (Project 1);

- develop a new product (Project 2);

- reduce faults (Project 3).

Each fulfils the definition of a business project by realising discrete benefits. Each will further the aims of the organisation to attain more revenue.

However, the investigative stages of Project 2 came up with a constraint on manufacturing the new product. It was not possible to do it in the time available and hence a decision was made to create the product in two phases. We now have:

- enhance the existing product (Project 1);

- develop a new product (Project 2);

- enhance the new product (Project 2A);

- reduce faults (Project 3).

Again, the Detailed Investigation Stage of Project 2 found, as part of the market research, that delivery time was a more important buying factor than realised. If amendments to Project 2 were made to incorporate this, it would have slipped and the revenue targets would have been missed. Consequently, a separate project was started off to take this aspect into account (Project 2B) (see Figure 14.1).

Notice what has happened. Projects spawn projects! A simple business objective of ‘Get $15m revenue’ has been translated into action in the form of five projects. When combined, these realise the benefit that the business requires.

Note that each project is defined such that it delivers a slice of that benefit, either independently or, as in the case of Projects 2 and 3, in series. Also notice that the business solution has been broken into discrete pieces. This has the effect of making them easier to implement and also allows benefits to be realised earlier than if the full scope were undertaken in a single project. You can also proceed with parts of the business programme as soon as you’re ready, while other parts are still in the fog.

Look at the projects that have resulted. Did they start off as fogs, quests, movies or painting by numbers? Probably the mix is as follows:

| Project 1 – enhance old product: | Painting by numbers |

| Project 2 – the basic new product: | Movie |

| Project 2A – the enhanced new product: | Quest or fog |

| Project 2B – decrease delivery time: | Quest |

| Project 3 – reduce faults: | Quest |

Project 2 has to use existing manufacturing plant for producing the new product. Project 2A needs to be converted to a painting by numbers project if it is to succeed. Projects 2B and 3 are more open ended. You may spend a fortune looking at possibilities but still not achieve a breakthrough. This, on its own, gives you a feel for the risk you are facing. You are not likely to have too much confidence in the benefits for those projects which finish more than a year from now. So, to make sure that your business programme is robust, you will need continually to reforecast your benefits. With a business programme like that shown, a related business planning and forecasting cycle of three months would probably be about right.

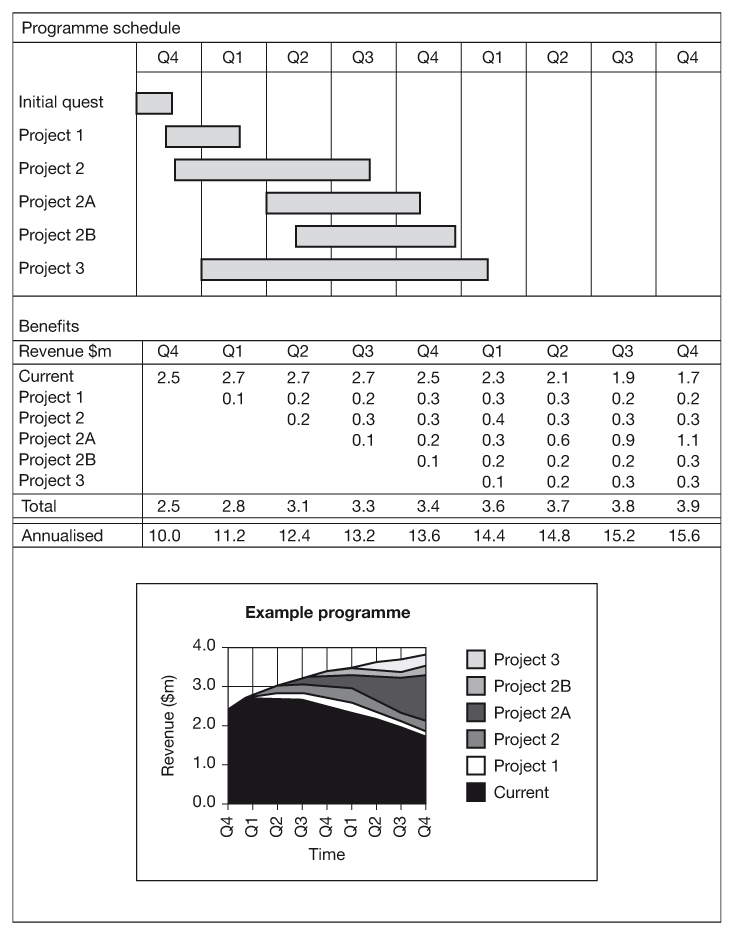

Figure 14.1 Business Programme schedule and expected revenue

The schedule for the projects within the Business Programme is shown at the top; each bar represents a project. The middle part of the figure shows the slices of revenue expected as a result of each project coming to fruition layered on the revenues you expect from the current product. This is shown graphically below.

The example is necessarily simpler than most situations you will find in practice as most Business Programmes comprise many more projects; nevertheless, it does demonstrate the key aspects of Business Programmes.

14.1 STARTING TO BUILD YOUR BUSINESS PROGRAMME

- List the primary business objectives of your organisation.

- Take the list of projects from Project Workout 3.2.

- Write each one on a Post-It Note.

- Start placing them on a wall or large white board in approximate chronological order.

- Group together in bands across the board those which you believe are targeted at fulfilling the primary business objective, selected from your list from step 1.

- Identify any interdependencies between projects (i.e. where one project relies on the deliverable(s) from another in order to meet its objective). Draw an arrow from the project creating the deliverable to the one requiring the deliverable.

- You may have a very complex picture by now! Try to simplify it. Projects with arrows going both ways between them are probably the same project even if you’ve defined them as separate. To test this, ask yourself if either one of the projects on its own produces any benefit to the business. If both projects are needed, they are the same project. Look for clusters of linked projects which have no arrows between them and other clusters. They may be your business programmes. Look for projects which don’t have significant benefits: mark them for possible termination (see p. 448).

- Look at the complexity of the interdependencies. The more complex and interwoven, the more risky the portfolio becomes. Think of ways of rescoping projects to create a set of programmes and projects which are relatively independent and will realise benefits early. Rescoping entails moving the accountability for producing a deliverable from one project to another.

CHANGES TO PROJECTS

In some cases, it is necessary to include new scope in an on-going project. Proper control of changes to the project scope are required to ensure that only beneficial changes are made. Chapter 25 explains this more fully.

What’s different about Business Programme management?

Business Programmes support business plans

Business Programme management provides a framework and practical tool for managing multiple programmes and projects in pursuit of defined strategic objectives. Business Programme management complements project and programme management but it takes a much broader, enterprise-wide view as it also includes benefits from current operations. Benefits from projects usually start after the project has been completed and the project team has been stood down. However, benefits from Business Programmes start to flow as soon as the first project within the business programme has been completed and its outputs incorporated into ‘normal business’. The key focus for Business Programme management is ensuring that current activities plus the programmes and projects as a whole provide the benefit required overall, regardless of the performance of individual components. Other differences are highlighted in the table that follows.

The advantages of taking a ‘Business Programme approach’ is that you are able, as we have seen from the simple example, to break up the required changes into achievable pieces and manage the implementation in a coordinated way. The change is therefore less likely to appear chaotic to the recipients (be they your own employees, your suppliers or your customers). You are also able to maintain a focus on the true business objectives of the Business Programme rather than be lost in the minutiae of delivery. This enables you to spot future gaps in benefits (either due to late projects or under-performance in benefit terms from ones already delivered) and take the necessary corrective action. You are also able to take a balanced view of the risks associated with a Business Programme.

| Business Programme management | Programme and project management |

| Broadly spread activity, concerned with overall strategic objectives as part of a business plan. It’s a continuous activity, with no defined end-point | Intense, and focused activity aimed at realising a ‘slice’ of benefit to the business programme as defined in a business case. It is a discrete activity, with a defined end-point |

| Is suited to managing and balancing a large number of constituent programmes and projects with complex and often changing interdependencies | Best suited to realising achievable benefits directly related to deliverables and outputs |

| Is suited to managing the impact of and benefits from a number of aligned programmes and projects in such a way as to ensure a smooth transition from the present to the new order | Is suited to delivering defined benefits within a given environment or scope |

| Includes benefits from current operations and from the outcomes of current and future projects | Includes future benefits of the project or programme itself |

| Is governed and constrained by organisation cash flow often seen as an annual budget | Is governed and constrained by a discrete programme or project budget |

BUSINESS PROGRAMMES IN SMALL AND LARGE ORGANISATIONS

I have already mentioned the difficulties that certain words can create; ‘programme’ is just such a problematic word (see pp. 62, 151). No matter how hard you try there will always be someone, somewhere who takes a different view. Accept it and don’t fight it. I expect there are many readers who say my definition of Business Programme is their definition of ‘portfolio’ – neither of us is wrong, but the key point is that, in your organisation, you must make sure you use words consistently in all your written documents, especially management reports. If you use the language consistently, people will gradually pick it up. In this book I distinguish business programme from programme from project. In a small organisation the business programme may represent the entire organisation, in which case the term becomes redundant – the organisation is the Business Programme. In larger organisations, the business plan will need to be divided into a number of Business Programmes each of which represents a part of the overall business plan.

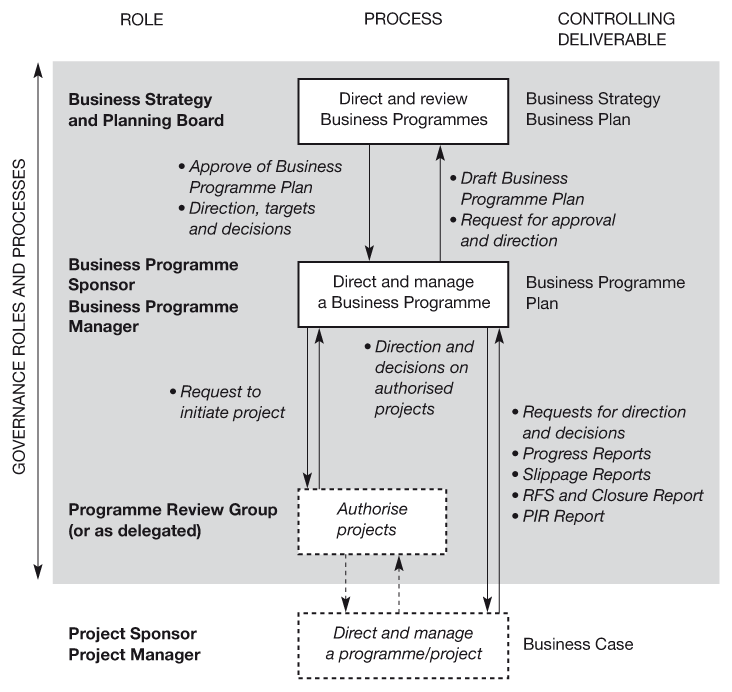

To test if your ‘programme’ and mine are similar, look at Figure 14.2. Business Programmes are above the ‘authorisation process’; they are the entities from which programmes and projects are initiated. They are governed by business plans, which usually give no authority for actual work to take place. Projects are below the ‘authorisation process’, being governed by business cases, which are used as the basis for authorising funding and resources to start work.

Business Programme accountabilities

If a Business Programme is a chunk of the business plan, who is accountable for it and what are those accountabilities? For small organisations, we have seen from the Point of Interest above that ‘Business Programme’ may be a meaningless term – the organisation is the Business Programme. It therefore follows that the role of the CEO or President and that of the senior team is relevant. These roles are primarily about the leadership of change and this requires both sponsorship (benefit/needs) and management (making it happen). For Business Programmes, I will call these roles ‘Business Programme Sponsor’ and ‘Business Programme Manager’, respectively.

If you are to have Business Programmes in your organisation, you will have a number of them and therefore you will need some body or individual accountable for directing them. There is no accepted term for such a body; for convenience I will call this the ‘Business Strategy and Planning Board’. Together, these business programme accountabilities form a key part in the governance of the organisation. The other aspect of governance is authorisation, where ‘permission’ is required before any work is started or funds spent. I deal with this in Chapter 15.

Figure 14.2 Business Programme accountabilities

The Business Strategy and Planning Board sets policy and direction for the whole organisation which are set out in the Business Strategy and Business Plan documents. They approve the plans for each Business Programme, each of which is directed by a Business Programme Sponsor and managed by a Business Programme Manager. Projects are initiated from the business programmes, through the authorisation process. Each project is directed by a Project Sponsor and managed by a Project Manager.

REARRANGING THE DECK CHAIRS

Naming roles and bodies can be very difficult. Each needs to be as self-explanatory as possible so that people can intuitively understand what each role is for. This can be doubly difficult in a project environment where the words ‘project’ and ‘programme’ take on so many different meanings. I have chosen a set of role names which are consistently applied throughout the book and which draw on associated terminology. I tend to use ‘sponsor’ where the role is ‘directing’ and ‘manager’ where the role is ‘managing’. You may call them what you want but I advise that:

- you make sure role names are distinct;

- you don’t choose names which will date;

- you keep the roles separate from job titles;

- if referring to ‘boards’, you keep the roles separated from the Board titles;

- having chosen your role names, you don’t change them.

Keeping roles and titles separate enables you to have a number of roles undertaken by a single person or body, thereby saving you from having to rewrite all your processes simply because of a minor change in personnel. For example, the CEO’s Leadership Team may take on the role of the Business Strategy and Planning Board and the Project Review Group. Changing role names is a common ploy by ‘new directors’ to show they ‘have arrived’ but all it usually does is confuse people. A colleague of mine once referred to this as ‘rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic’.

The Business Strategy and Planning Board is accountable to the Chief Executive Officer for setting business strategy, directing corporate change and ensuring the business programmes realise the benefits required.

Business Strategy and Planning Board

- Sets strategic direction, policy and priorities.

- Sets business and benefits realisation objectives and constraints for the organisation as a whole and for key elements of each Business Programme, to ensure maximum benefits and progress toward the strategic vision.

- Allocates funding and resources to each Business Programme and function, through the approval of the business plan and each Business Programme Plan within it.

- Monitors and reviews benefits realisation, delivery and costs from all Business Programmes, directing corrective action where appropriate.

The Business Programme Sponsor is accountable to the Business Strategy and Planning Board for directing the Business Programme, ensuring that the portfolio of projects and activities (Business Programme) within his/her scope realises the required benefits.

Business Programme Sponsor

- Provides business direction to the Business Programme in terms of making decisions, initiating new projects, terminating unwanted projects and resolving issues.

- Approves the Business Programme Plan prior to authorisation by higher authority.

- Ensures that the combined benefits for the Business Programme are realised.

- Ensures that the scope of the Business Programme covers the needs of the business.

- Directs priorities between contending projects and activities within the Business Programme.

The Business Programme Manager is accountable to the Business Programme Sponsor for day-to-day management of the Business Programme, ensuring that the portfolio is planned and managed to ensure maximum focus and speed of benefit realisation.

Business Programme Manager

- Prepares and maintains a plan of scope, timescale, benefits and costs for the Business Programme, including reserve for as yet unidentified projects and activities.

- Selects and manages the portfolio of projects within the Business Programme to realise the required benefits and to ensure that the contributions of all parts of the organisation are taken into account.

- Approves and authorises projects as delegated.

- Monitors performance against the Business Programme Plan, initiating corrective action and ensuring the integrity of the plan (including interdependencies).

- Provides regular progress reports to the Business Programme Sponsor and senior management.

- Ensures use of best practice methods and organisation procedures.

- Assigns the project sponsor role for each project within the Business Programme.

- Approves and authorises projects as delegated.

- Ensures the projects are progressed, by the project sponsor, through the authorisation process.

A Business Programme Board, if required, would support the Business Programme Sponsor in carrying out his/her accountabilities, particularly in respect of senior management alignment and engagement.

A Business Programme Office would provide the Business Programme Sponsor and Manager with the necessary administration, expertise, knowledge and resources to ensure that the above accountabilities are undertaken effectively. See Chapter 17 for more on this.

BUSINESS PROGRAMMES AND CROSS-ORGANISATION LEADERSHIP

Test the business programme roles. Replace the words Business Programme Sponsor by CEO and the business by shareholder. Notice the fit? The implication is that the role is truly one of leadership and not one of functional management. Business Programme Sponsors may be top directors or executives who have some functional accountability but, in the world of projects, they need to take on a cross-organisation role as we know any single function can achieve very little on its own. You will see a similar correlation between COO (or deputy CEO) and Business Programme Manager.

14.2 CHUNKS OF CHANGE

Look at any one of your longer running projects, say over a six-month duration. Critically review it to decide if you could have implemented it in smaller pieces. What was the minimum that was needed to be done?

Look at projects you are starting off now. Can these be divided into more digestible pieces?

Forecasting cycles

How often do you do your business forecasting? Annually? Quarterly? Monthly? If you do it only annually, consider how you can have confidence in the forecasts. Do you really know so much about the future that you could forecast a year in advance? Is your organisation really in such a slow-moving competitive environment?

Note: Forecasting is predicting what your management accounts and information systems will tell you in the future. Setting a target is not forecasting.

Managing the portfolio

In Chapter 1 we identified a number of commonly found deficiencies in how projects are managed. A key factor in the success of your organisation is the speed and effectiveness with which you can stay ahead of, or respond to, changing circumstances. Unless deficiencies in implementing the necessary changes are addressed, you will always be losing time and energy in fighting internal conflicts rather than addressing real external opportunities and threats.

No organisation, however, has just a single project, there are always several on the go and (as we have seen from the example on p. 163) ‘projects spawn projects’ there will always be more to come, either as part of a programme or as stand-alone initiatives. Directing this ‘portfolio’ of projects is a senior management task, as it is this ‘bundle’ of projects that will take you from where you are now to your, hopefully, better future.

A portfolio is a range of investments held by a person or organisation. A business programme is a very special type of portfolio.

I also use the word portfolio to represent any bundle or grouping of projects which we may choose to select for the convenience of management, reporting or analysis. After all, projects are investments of time and resources made by organisations to achieve benefits. Thus, the full set of projects undertaken within a organisation is its organisation portfolio. The set of projects held by a project sponsor is a sponsorship portfolio. The set of projects project managed by a person or function is a management portfolio.

At an organisation portfolio level, the actual performance of individual projects (or even programmes) becomes less critical. You can accept some being terminated, some being late, some costing too much or simply delivering the wrong thing. What is more critical is that the whole portfolio performs well enough to move your business forward as effectively and efficiently as possible. Like investments in the stock market, your portfolio of projects should be balanced with respect to risk. You should have some (but not too many!) projects which are risky, which will create a step change if they work or which are pushing forward the boundaries of your thinking and capability. Without these, you will be too rooted in today’s paradigms and not reaching for new horizons.

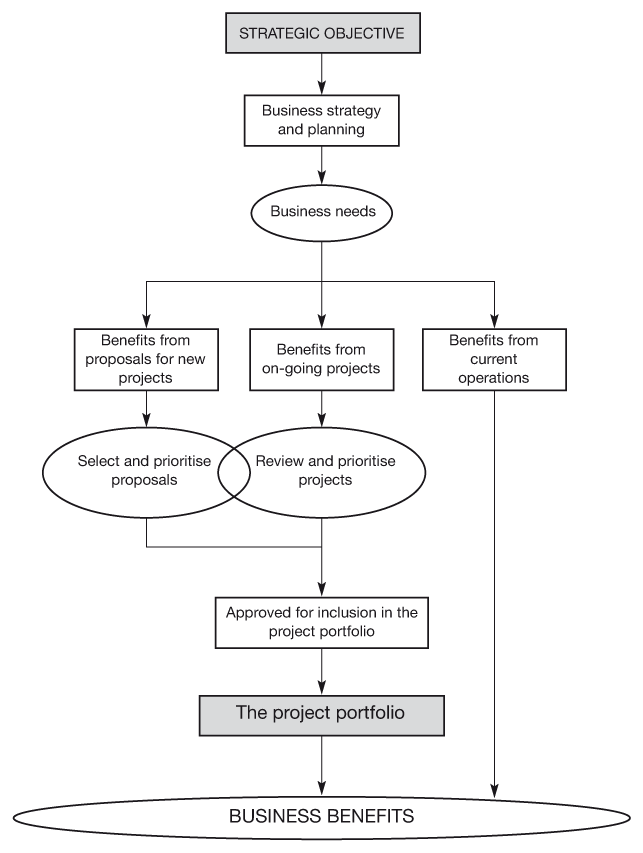

Figure 14.3 Proposals and projects in the context of strategy

Any change project you have starts as a proposal, becomes part of the project portfolio and eventually its output is subsumed into ‘business as usual’. The speed and reliability with which you can do this is a critical success factor for your organisation. Compare the build-up of benefits in Figure 14.1 with this diagram to see how each part fits.

Figure 14.3 illustrates the framework. Future benefits come from three sources in your organisation:

- the operation of the organisation as currently set up;

- the changes created by projects you already have under way;

- proposals you have identified which are yet to be started (or not even thought of!).

Any change starts as a proposal, becomes part of the project portfolio and eventually its output is subsumed into ‘business as usual’. The speed and reliability with which you can do this is a critical success factor for your organisation.

Prerequisites for effective portfolio management

So what are the prerequisites for managing a portfolio on a organisation-wide basis? The central ‘plank’ to managing a portfolio is reliable management of the individual projects:

- A staged approach: you should use a simple staged framework for the management of your projects to enable key decisions to be made at known points (gates).

- Good project control techniques: you should ensure that a basic foundation knowledge of project management techniques is understood and practised.

To make these work, you must have a organisation-wide environment (Figure 14.4) for:

- Strategic alignment: ensuring you choose the ‘right’ projects to turn your strategy into action.

- Decision making: you must make decisions which are respected, are the right ones and are made in the best interest of your organisation.

- Resource management: you must ensure that you have visibility of the availability and consumption of resources you need to undertake your projects and operate the outcomes.

- Business planning: you should make the management of your portfolio of projects a part of your business – it is not an optional extra. Projects are ‘business as usual’.

- Project register management: you need to know what projects you are doing, when, why, who for and who’s impacted.

- Fund management: you should ensure funding follows the projects you want to undertake.

The lack of any of these capabilities has implications on your organisation:

- Poor strategic alignment: you may end up doing the wrong projects.

- Poor decision making: decisions made in one part of the organisation may be overturned by another part, decisions may take too long or too many projects may be initiated.

Figure 14.4 The environment for managing your portfolio of projects

The staged project framework is the central ‘plank’ around which the key aspects of managing the portfolio revolve. While shown as separate ‘items’ they in fact have a large degree of interdependence.

- Poor resource management: you don’t know if you have sufficient resources to finish what you’ve started, let alone start anything new.

- Poor business planning: if you do not integrate the ‘future’ as created by your projects into your business plan, how will the plan make any sense and how will you know if you have anyone to use the outcomes?

- Poor project register management: if you have no list of or method for tracking your projects, they won’t be visible and people are unlikely to know what has been authorised and what has not. You will not know which projects are interdependent. You risk overloading your organisation with change.

- Poor fund management: you won’t know if you have the funds to complete the projects you have started or be able to fund new ones. You will spend your money on the wrong things.

Business programmes are a vehicle which enable you to tackle these needs. Business programmes are chunks of your strategy and your business plan. They are the link between what you do now and what you will do in the future. They therefore also form the most appropriate vehicle for dividing up your organisation’s spending, with the highest priority business programmes attracting the greatest investment. Finally, they are the control environment for ensuring you do not overload your organisation with ‘too much change’.

14.3 THE PROJECT PROCESS ENVIRONMENT

The list of factors needed to control a project portfolio is long. In this workout you should assess your current ‘health’ and use that as a prompt for discussion to help you decide which you need to concentrate on first.

Take each in turn and, with respect to projects and change initiatives in your organisation:

- Assess, without any in-depth analysis, the effectiveness of each competence – 0 = no capability, 5 = excellent in your organisation.

- Discuss the implications on your organisation of any lack of competence in each area and note them down. Do not expect to be excellent in every area.

- If you are basically satisfied with your assessment, consider whether the competencies you have actually work together as whole.

| Competence | Score | Implications |

| Strategic alignment | ||

| Decision making | ||

| Resource management | ||

| Business planning | ||

| Register management | ||

| Fund management | ||

| Project management |