4

Leadership role in the management of

knowledge structures and culture

Leading edge organizations constantly and consistently learn. It is the task of organizational leaders to install a culture and climate that nurtures and acknowledges knowledge at every level. Notwithstanding the fact that leaders are critically important, they alone are not sufficient to build cultures of sharing and learning. To do this leaders must amplify their energy and direction by using the management layers below them. This requires them to identify, recruit, develop, train, encourage and acknowledge knowledge champions and advocates throughout the company.

Leadership criteria

To build a successful and sustainable culture of knowledge, senior management needs to accomplish two broad tasks. First, leaders need to be acutely sensitive to their environment and acutely aware of the impact that they themselves have on those around them. This sensitivity enables them to offer an important human perspective for the task at hand. This is critical because it is only with this awareness that the leader can begin to bridge the gap between ‘leader-speak’ and the real world of organizational culture. The second factor, is the ability of leaders to accept and deal with ambiguity. Knowledge management cannot occur without ambiguity, and organizations and individuals that are not able to tolerate ambiguity in the workplace environment and its relationships will reproduce only routine actions. Learning structures, for example, cannot have all attendant problems worked out in advance. Leaders need to build a deep appreciation of this fact otherwise there is a simple tendency to create a sameness and a culture of blame. Tolerance of ambiguity allows space for risk taking, and exploration of alternative solution spaces that do not always produce results. This hedges against constant deployment of tried and tested routines for all occasions. As Tom Peters once suggested, most successful managers have an unusual ability to resolve paradox, to translate conflicts and tensions into excitement, high commitment and superior performance.

Leadership traits that exemplify successful knowledge management companies from less successful firms are:

1 Top management commits both financial and emotional support to knowledge management.

2 They promote knowledge sharing through champions and advocates of learning.

3 They promote knowledge sharing and learning by their own personal actions and behaviours.

4 They make realistic and accurate assessments of the benefits of managing knowledge.

5 They understand clearly the barriers to sharing from the employees point of view, as well as from the organizational structure point of view.

6 They ensure that knowledge projects get the necessary support from all levels of the organization.

7 They ensure that structured processes and systems are set in place to aid the process of knowledge capture, learning and dissemination.

8 They manage the formal as well as understand the critical role of the informal in managing for knowledge.

9 They appreciate the dynamics of knowledge management and help it move forwards rather than institute tight control systems.

Senior management play a pivotal role in enhancing or hindering knowledge sharing. If senior management are able to install the above type of practices then they effectively seed a climate conducive to sharing. It is important to note that it is not sufficient to only emphasize one or a few practices. Climates are created by numerous elements coming together to reinforce employee perceptions. Weaknesses or contradictions even along single dimensions can quite easily debilitate efforts. For example, if rewards are not structured for knowledge sharing but are given for efficient performance of routine operations then, no matter how seductive the other cues and perceptions, employees are likely to respond with caution and uncertainty. This is particularly the case because perceptions of the climate are made on aggregates of experience.

Senior management create climate not by what they say but by their actions. It is through visible actions over time rather than through simple statements that employees begin to cement perceptions. It is only when employees see things happening around them, and do things that push them towards knowledge sharing that they begin to internalize the values of knowledge sharing and transfer. Leading companies emphasize all the systems of organizational function towards knowledge sharing (who gets hired, how they are rewarded, how the organization is designed and laid out, what processes are given priority and resource back-up, and so on).

Empowerment

Empowering people to learn and share insights is one of the most effective ways for leaders to mobilize the energies of people. Leadership support and commitment to empowerment gives people freedom to take responsibility for knowledge sharing. Empowerment in the presence of strong cultures that guide actions and behaviour produces both energy and enthusiasm to learn and share knowledge. Employees themselves are able to devise ways that allow them to innovate, learn and accomplish their tasks. The only serious problem with empowerment occurs when it is provided in an organization without a strong value system capable of driving activities in a strategically aligned and unified manner. In such circumstances, empowerment is little less than abdication of responsibility, and when responsibility and power is pushed downwards, chaos typically ensues.

Even with empowerment, knowledge-sharing actions can be incapacitated. Often people encounter organizational barriers which inhibit sharing. Some typical barriers to sharing are listed below:

- self-imposed functional perceptions

- unwarranted assumptions

- ‘one-correct-answer’ thinking

- failure to challenge the obvious

- pressure to conform

- fear of looking foolish.

Senior management can also quite easily kill off initiatives by using phrases such as:

- ‘We have never done things that way.’

- ‘If it's that good, why hasn't someone thought of it before?’

- ‘Has it been done somewhere else?’

- ‘Yes, but…’

- ‘It can't be done that way.’

- ‘Its impossible.’

- ‘It will cost too much.’

Actions that need to be addressed in order for the empowerment (Galbraith, 1982; Hsieh, 1990) to contribute to knowledge sharing are listed below:

1 Establish meaningful ‘actions’ boundary. For employees to share knowledge they need to understand the primacy of the knowledge agenda, and need to understand how far they are being empowered to achieve these ends. Successful companies are able to draw an ‘actions’ boundary through a process of explicitly defining the domain of action and the priority, and the level of responsibility and empowerment provided to reach these ends. Often such transmission occurs through mission and vision statements. Devised correctly, these statements can act as powerful enablers; incorrectly, they can be just as powerful disablers, breeding cynicism and discontent.

2 Define risk tolerance. Employees need to know the level of risks that they can safely take. This helps them to define the space within which they are allowed to act in an empowered manner, and the occasions when they need to approach organizational ratification for engaging in actions. For example, employees needs to understand how much time they can spend on their pet knowledge projects, and how much effort they need to ensure that their ‘routine’ operations are not made suboptimal. They need also to understand the penalties if inefficiencies creep into aspects of their task. In this way, understanding of risk provides a clear definition of the priority and space for knowledge actions. Without knowing risk tolerances that exist within the organization, employees tend not to be willing to try to innovate, or engage in activities that are a departure from tradition. The best way for leaders to define the action space, is not to be so precise as to discourage risk taking and innovation, but to stipulate a broad direction which is consistent and clear. This means that, as leaders, they must be capable of accepting ambiguity, and able to place trust in an employees’ ability to stretch out to goals rather than prescribe details of specific actions which stifle and smother creative actions.

3 Structure involvement. Involvement is not something that just occurs on its own. Senior management need to design it into their organization's ways of buying involvement. Involvement requires emotional encouragement, as well as an infrastructure to create possibilities of involvement. Organizational design and layout can be used to create a physical environment to enhance interaction. Awards and special recognition schemes are another mechanisms to encourage ‘buy-in’ to knowledge sharing as a philosophy and way of organizational life. Establishing specific mechanisms for structured involvement such as communities of practice (formal or informal teams that have a shared interest in an area), quality circles and creativity circles are devices to encourage active participation into the knowledge programme. Without direct structures to induce sharing, commitment to knowledge remains an empty management exhortation and produces empty results.

4 Accountability. A very common problem in some empowered organizations is that everyone is encouraged to participate in cross-functional process involvement, to the extent that almost everybody loses track of who is accountable for what. The result of unrestricted and uncontrolled empowerment is chaos. As new processes are put in place then new forms of behavioural guidance must be provided and must be accompanied by redefinitions of responsibility. While empowerment on the surface look like an unstructured process, in reality it is anything but that. It is in fact a clear definition of bounds in which the individuals are allowed to exert creative discretion, and the responsibility that they must execute while engaging in their total task as employees of the organization.

5 Action orientation rather than bureaucracy orientation. For knowledge sharing to occur leaders must ensure that there are few encumbrances that suffocate attempts at sharing. One primary culprit of this is overly bureaucratic procedures for rubber-stamping approval or reporting requirements. Faced with such obstacles a lot of employee initiatives fail. In fact, a large proportion of suggestions and learning insights fail because they never make it to the implementation stage. Most are ‘killed off’ because of bureaucratic protocols, in particular the failure of the protocols to respond with sufficient speed due to a favourable or unfavourable response to a particular idea. Employee innovation and learning is not usually the stumbling the block. More often it is the burdensome and unwieldy organizational processes and structures that debilitate efforts through their unresponsiveness. Leadership must therefore commit to re-engineer unfruitful elements of bureaucracy and processes, and structure it such that they lay the foundation for enhanced sharing and learning.

Corporate missions, philosophy statements and knowledge culture

We wonder whether it is possible to be an excellent company without clarity in values and without having the right sort of values … clarifying the value system and breathing life into it are the greatest contributions a leader can make.

(Peters and Waterman, 1982)

Having a clear corporate philosophy enables individuals to coordinate their activities to achieve common purposes, even in the absence of direction from their managers (Ouchi, 1983). One effect of corporate statements is their influence in creating a strong culture capable of appropriately guiding behaviours and actions. However, there is also a degree of doubt as to whether vision-mission statements have any value in driving the organization forward. Most statements encountered often are of little value because they fail to grab people's attention or motivate them to work towards a common end (Collins and Porras, 1991). Others have gone even further, dismissing most corporate mission statements as worthless platitudes, which often end up just restating necessities as objectives. For example, ‘to achieve sufficient profit’ is like a person saying his or her mission is to breathe sufficiently.

Despite these concerns, Ledford, Wendelhof and Strahley (1994) suggest that, if correctly formulated and expressed, philosophy statements can provide three advantages:

1 The statements can be used to guide behaviours and decision making.

2 Philosophy statements express organizational culture, which can help employees interpret ambiguous stimuli.

3 The statements contribute to organizational performance by motivating employees or inspiring feelings of commitment.

It is worth bearing in mind that the corporate statement does not have to move mountains to make a cumulative difference in firm performance. If the individual employees become just a little bit more dedicated to knowledge sharing and transfer, exert just a little bit more effort towards learning, care a just a little bit more about their work, then the statement produces a positive return on the investment needed to create it.

So what makes a statement effective? Ledford, Wendelhof and Strahley (1994) suggest four basic guiding principles to bring a statement to life:

1 Make it a compelling statement. Avoid boring details and routine descriptions.

2 Install an effective communication and implementation process.

3 Create a strong linkage between the philosophy and the systems governing behaviour.

4 Have an ongoing process of affirmation and renewal.

What we have learnt is that the soft stuff and the hard stuff are becoming increasingly intertwined. A company's values – what it stands for, what its people believe in – are crucial to its competitive success. Indeed values drive the business.

(Robert Haas, CEO of Levi Strauss)

Leadership actions for knowledge culture

Despite all the mystique surrounding the concept of culture, there is little that is magical or indeed elusive about it. The problem is primarily about deciding clearly what are the desired appropriate norms, specific attitudes and behaviours and then identifying and building norms to reach out to these expectations.

Turning attention to how culture is to be developed and managed in organizations, we observe that while all companies have cultures only a few systematically attempt to manage it. O'Reilly (1989) suggests four key steps for this. In these steps, what varies across companies is not what is done but the nature and degree to which these are utilized.

Step 1 The process begins with the actions and words of senior management.

Step 2 It then has to be effectively communicated to all levels. The communication maybe explicit as encapsulated by mission and philosophy statements.

Step 3 Approval: even if actions are not explicitly stated, they still are inferred by those lower down the organizational ladder by discerning actions that are approved.

Step 4 Reward: rewarding certain types of behaviour serves to embed that behaviour by acting as an outward and explicit cue of approved actions.

If management is consistent and does not contradict constantly its actions and words, then members of the organization will begin to develop consistent expectations about what is important. Through this consensus process, clear norms emerge.

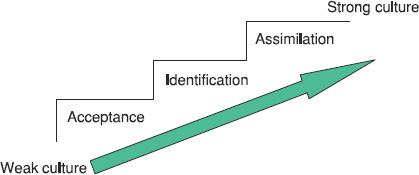

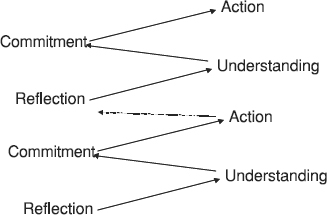

Fig. 4.1 Stages in commitment

For the change in norms to occur, individuals go through a threestage process of commitment (O'Reilly and Chatman, 1986) (Figure 4.1).

At the first stage, individuals simply comply either because they are being rewarded or they are being coerced to do so by threat of punishment. At the second stage, individuals accept the ‘exchange’ relationship or behaviours being requested by the organization. Development to this stage only occurs if there is a clear level of satisfaction between the individual and the organization. Individuals at this stage may attach a sense of pride and belonging to the firm. The final stage, is when the individual's and the organization's values converge. At this stage, the person and the organization act in synchrony. Here, individuals find the organization to be intrinsically rewarding and congruent with their own personal values. If this final stage is attained for a majority of the organizational population, then one may rightly say the company possesses a strong culture.

Teams for knowledge and learning

Many firms are entrusting their knowledge and learning to teams. Many different formats of teams are used. The two most common formats within knowledge programmes are:

- project teams – usually formally constituted to solve particular problems

- community of practice – a grouping of individuals who share a common interest. Communities of practice can be either formal or informal, though there was a tendency previously to consider communities of practice to be primarily voluntary and informal.

Typically, these teams and communities of practice are multifunctional, and may even include external representatives from leading suppliers, customers, and re-sellers.

Leadership strongly influences communities of practice and project teams. Generally, we can say that team leaders enhance the impact of such groupings by:

- clearly communicating the organization's expectations to team members

- fostering high levels of communication within and outside the team

- creating a climate that raises morale and energizes team members

- taking responsibility for the team's goals

- guiding and sharing the team's burdens, and interfacing with key external constituents

- ensuring they are provided with high levels of autonomy and support from their superiors in the organization

- involving participants with differing and multiple perspectives

- balancing demands made by different organizational constituents

- ensuring adequate technical support

- facilitating a high degree of human interaction

- reducing destructive conflict.

Knowledge and learning holds little significance if it takes too long or costs too much. Effective knowledge leaders are those who increase creativity and deliver knowledge to the right person at the right time in the right format, quickly and cheaply.

Knowledge managers often find their companies to be compartmentalized, functional entities that resemble a salad bowl of subcultures with disparate thought-worlds and functional processes. In these instances knowledge creation and sharing is inordinately difficult. The problem is that such independently made decisions may make micro-sense to one department at one time yet make macro-nonsense to other departments and the organization. The role of knowledge leaders is to overcome functional differentiation and foster collaborative decision making. Leaders must create a social environment in which teams come to resemble less a battleground embedded with turf protection behaviours, and more of a sanctuary in which people with divergent orientations and talents can share hidden agendas, ask for help, take risks and develop collaborative relationships with others. Leaders must build trust, foster openness and encourage risk taking so that people's creative talents are constantly focused towards improvement actions.

Managing teams and communities of practice

The advice on how to manage teams and communities of practice is both varied and vast. Nevertheless, a few guidelines can be surmised. According to Jassawala and Sashittal (2000) these are to:

- ensure commitment

- build information-intensive environments

- act as facilitators not heroes

- focus on learning.

Ensure commitment

Ineffective knowledge processes result from low commitment to decisions and disconnection between processes and subprocesses. The challenge is to get team members to own the knowledge-sharing and learning process, i.e. get people to commit to the inputs and also take responsibility for the outputs. If this can be done then significant improvements are likely. Knowledge leaders must:

- increase participants’ personal, emotional commitment to the team/community of practice

- during interactions with team communities, shape people's vocabularies and language to favour the view that all individuals and functional groups, as well as key customers and suppliers, are insiders

- interact with team members in ways that makes their interdependence apparent

- act in ways to ensure that members feel a greater sense of control over their community's destiny by loosening control over information and resources

- encourage community members to develop their own protocols, identify their own criteria, assign their own priorities, make their own decisions and design their own work flow.

This often newly acquired autonomy is instrumental for transforming a group of disinterested participants into a team of members who hold a stake in their interdependence and social relationships, and the outcome is knowledge sharing and dissemination of learning. Ensuring commitment has much to do with team leaders’ efforts to facilitate the process by which team communities blend their loyalties and develop integrated identities of departmental and team membership.

Build information-intensive environments

Communities work most effectively in open information-rich environments. Information-poor environment are characterized by:

- senior management's actions suggesting tight control and releasing information on a need-to-know basis

- constantly supporting one dominant functional group or coalition

- supporting safe decisions that are devoid of insights or vision

- a tendency to rely on innuendo and soft data (i.e. using information that people with differing views cannot reconcile)

- a propensity to use information as a weapon that prevents others from succeeding and helps people hide from responsibility.

Good managers favour information sharing, airing of divergent views, openness and holistic thinking.

Act as facilitators not heroes

There is a clear link between senior management's propensity to micro-manage and shape community activities with disinterest of team members. Senior management's direct exercise of power over knowledge structures such as communities of practice often leads to feelings of powerlessness among team members. The outcome is apathy and responsibility shifting. Community participants lose interest in taking the initiative and risks because they feel powerlessness. Under these conditions team participants often feel absolved of their collective responsibility towards creating new outcomes.

Managing for knowledge and learning necessitates a fundamentally different type of leadership than the customary view of the leader as central actor in the unfolding drama. The limelight hero in the knowledge and learning drama is replaced by the leader as facilitator. The view that leaders ought to control and orchestrate work activity is replaced by the view that leaders act in ways that make them redundant.

Leaders as facilitators take steps to shield community grouping from the bureaucratic tendencies of the larger organization. Although many of these actions may scarcely be noticeable, since most of these actions may occur outside of memberships’ purview, they are important to the success of the community. In one sense, the leader's role is that of insulator from outside forces.

Focus on learning

Inflexibility, rigidity and maintenance of the status quo leads to poorly managed learning processes. The hustle of the day-to-day task environment and frequent involvement in fighting fires usually deflects attention from attempts and thoughts towards learning and improvement. Unless, there is an explicit effort to continually test and question assumptions and actions, then few learning insights are likely. Indeed, without such emphasis on learning and change, communities of practice can fast become forums existing only for acting out rivalries.

Knowledge managers need to transform the nature of learning that occurs within their teams and communities. They can do this by enhancing the community's ability to adapt and improvise through:

- investing in training about the process of learning

- asking community members to identify and evaluate the key premises that guide their thinking and actions

- asking team members to regularly and in a meaningful way assess their knowledge creation performance

- constantly checking for double-loop learning. For instance, effective team managers often explain the premises guiding their decision making and actions. They also make questioning fundamentals permissible among team members. This creates a double loop of thinking and learning because, first, the link between their actions and outcomes is examined for insights and, second, implicit theories of action are examined and evaluated in order to understand how and why those decisions were made and those actions were taken in the first place. Open discussion of premises and theories of action is the key difference between teams that learn and adopt new behaviours as opposed to those that resist learning and resist change

- placing emphasis on experimentation and risk taking.

Management considerations for different types of knowledge and learning outcomes

An important consideration to bear in mind in the process of managing projects and communities for knowledge is the different types of outcomes that are being developed and sought. Two variant outcomes should be explicitly acknowledged since they hold broad implications for the management of knowledge structures: teams and communities that are primarily seeking to exploit extant knowledge against those aiming to develop radically new knowledge. These two polarities can be captured by exploitation at one end and exploration at the other (Zack, 1999):

1 Exploration provides the knowledge capital to propel the company into new niches while maintaining the viability of existing ones.

2 Exploitation of knowledge provides the financial capital to fuel successive rounds of innovation and exploration.

The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive processes, though for many companies they seem to be. An organization may be developing one area of knowledge while simultaneously exploiting it. Companies must appreciate that the two polarities may require different approaches in management. The ideal is to maintain a balance between exploration and exploitation within all areas of strategic knowledge.

In the explore process, the greatest challenge is to create new knowledge, whereas in the exploit process the greatest challenge is to transfer knowledge. Exploration without exploitation cannot be sustained in the long run because it uses resources without generating returns. Exploitation without exploration is also not sustainable because, ultimately, the knowledge spring will run dry as today's knowledge becomes obsolete. Only those companies that closely integrate knowledge exploration and exploitation can become true knowledge and learning organizations. They will be able to sustain their energy over the long term.

The distinction has an important bearing on management of the knowledge processes. The reason is that the two types need to be accommodated very differently within the overall knowledge management process. Teams and communities that are primarily involved in exploitation activity can potentially be managed through more structured and milestone-led controls. In contrast, managing exploration projects and communities in the same way will most likely lead to failures. The organization must be prepared to accept that each warrants a different approach not only in structuring, but also in measurement metrics, rewards, control and so on. The organizational challenge is actually even greater because it is likely that the same team or community participants engage in knowledge creation and exploitation simultaneously. The first obstacle to overcome is understanding the dichotomy and the second is to manage it.

Individual roles for knowledge creation and transfer

Knowledge leaders are positioned to play a strategic role in linking people and process through their actions of control. Good knowledge managers have come to recognize that their role has expanded to incorporate the need for them to be communicators, process and structural architects, and designers of an evolving company culture. Many knowledge leaders, through their training and experience, have come to understand knowledge management as a whole approach of doing business. To design for knowledge is to plan for knowledge, and to plan for knowledge one needs to consider the strategic whole. Knowledge architects have to bridge the aesthetics of theory with the hard realities of the world of business. They can do this by bridging the link between people, technology and process.

Knowledge and learning teams usually include participants from different disciplines, organizations and cultures because the creation of improvements and innovations often requires specialist from a variety of disciplines and contexts, and it is quite possible that not all may work in one organization, company or country. These participants come to the project task with preexisting patterns of work activities, specialized work languages and different constraints and priorities. Knowledge managers need to explore and integrate these differences. When the context is not explored, project team members may make decisions that have a negative impact on another's work and on the project development process as a whole.

An important aspect of knowledge exploration and exploitation is collaboration through interaction and communication. Interaction and communication are human behaviours that facilitate the sharing of meaning and which take place within a specific context. Individuals who facilitate communication within the knowledge process facilitate integration and thus contribute heavily to a programme's success. A type of role that appears to be of particular importance to knowledge exploration and exploitation is one often referred to as the boundary-spanning role. Sonnelwald (1996) identified a variety of boundary-spanning roles. These roles occur at five levels:

1 Organization

(a) Sponsor: helps secure acceptance and funding for the project and presents a case for the project organization wide and externally.

(b) Interorganizational star: interacts with others across corporate boundaries.

(c) Intergroup star: plans and co-ordinates activities across groups and represents the group in planning discussions.

(d) Intra-organizational star: filters and transmits organizational project information across functions and processes.

(e) Intra-group star: facilitates interaction among group members.

2 Task

(a) Intertask star: facilitates interaction and negotiates conflict between people doing different project tasks.

(b) Intra-task star: facilitates interaction and co-ordinates activities within a task.

3 Discipline

(a) Interdisciplinary star: integrates knowledge from different disciplines and domains to create solutions to project problems.

(b) Intra-disciplinary star: transmits information about new developments within a discipline.

4 Personal

(a) Interpersonal star: facilitates interaction among individuals.

(b) Mentor: filters and transmits career information to individuals.

5 Multiple

(a) Environmental: transmits information from outside the project context, but relevant to project participants.

(b) Agent: facilitates interaction and arbitrates conflict among all design participants.

Participants in the knowledge and learning process may assume one or more of these roles and may change roles during the knowledge exploration and exploitation processes. Strategies and skills needed to perform the majority of boundary-spanning roles are acquired on the job, over the course of many years of professional experience. For example, the interpersonal, intra-disciplinary, intra-task, intra-group and intertask roles can be assumed by many participants with minimal experience (around one year). The skills for these roles can be, and most likely have been, obtained during the individual's formal education. However, the interorganizational star, mentor and agent roles need participants with considerable experience (around a minimum of eight years) and the interdisciplinary star, intergroup star and environmental scanner roles require an even greater number of years of professional experience. This appears to suggest that participants learn the strategies and skills for such higher roles after many years of work experience. The different levels of facilitative skills hold obvious implications for structuring designs for knowledge management and learning.

Managing the individual towards learning

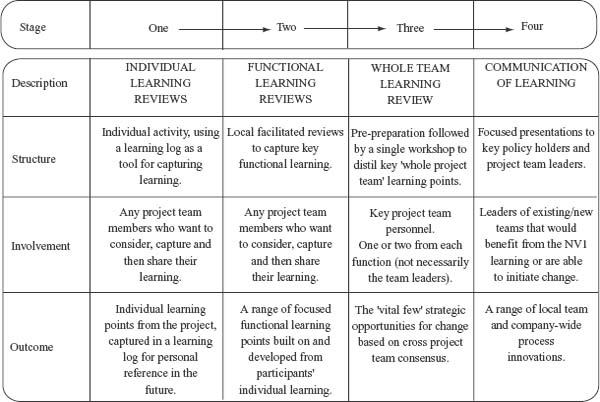

Barker and Neailey (1999) proposes an individual–team learning methodology which depicts the relationship of individual learning to team and higher learning. It consists of four stages, starting with an individual learning review process and then progressively moving through stages to develop the learning to the level of the whole project team. (Figure 4.2).

Stage 1 Individual learning reviews

The stage attempts to achieve full involvement through a process in which all team members are encouraged to reflect on and record their own learning. This is conducted using a learning log, (a tool to assist team members to structure their thinking). The learning log includes an introduction to the review process and a company perspective on the need to capture and share learning. There are a number of advantages of using the learning log:

Fig. 4.2 The individual-team learning methodology. Source: Barker and Neailey (1999)

- With the structure following the natural stages of the project, it enables individuals to place themselves at specific points in time and helps provide detailed and specific recollection of learning.

- It supports the aim of early divergent thinking.

- It provides a starting point anchored in familiar territory – what they learned as individuals.

Stage 2 Functional learning reviews

After a period of time to allow for individual reflection and completion of the learning logs, a series of functional reviews need to be arranged. Given the highly divergent nature of learning likely to be recorded within the individual learning logs, it is the purpose of the functional review stage to encourage functional groupings (engineering, sales and marketing, manufacturing, etc) within the overall project team to combine, converge and identify the more fundamental learning points relevant to each particular function.

Stage 3 Whole-team learning review

Following work at the functional level, the third stage of the methodology brings all the leaders together, converging the learning to a ‘whole project team’ level. The stage starts with pre-work (a request to review the learning points from functions other than their own). A workshop can then held to consolidate the functional learning into a single set of key project team learning points.

Stage 4 Communication of learning

A key element of success is a powerful process of communication. Powerful communication creates a ‘pull’ for the learning. The aim of the communication pull is to encourage those who can implement the necessary changes into team processes and procedures to actively seek the learning from key fact-holders. This is because while a lot of learning may be gleaned from the collective history in the form of written material, the really deep learning transfer occurs through conversations between the project team members and members of other project teams.

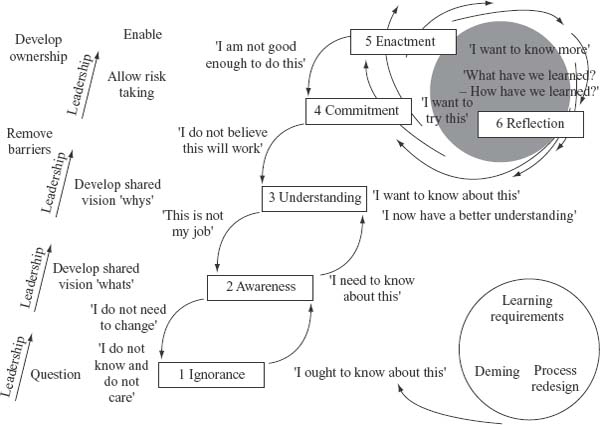

However, for an individual to learn he or she must move to a learning and knowledge-sharing mentality. The individual has to be motivated. The motivation can be intrinsic, i.e. from within the individual, or extrinsic, i.e. imposed from outside, usually by the organization. Buckler (1996) proposes that an individual moves through a number of stages in the process of becoming learning orientated (Figure 4.3).

These stages of individual development are:

1 Ignorance. If we accept ‘No one knows what they don't know’, then no blame can be attached to any individual who finds himself or herself in a state of ignorance. This stage is the starting point for everyone. Also, it is the easiest stage to move from by enquiring.

2 Awareness. After awareness, motivation is needed from the individual to put in the effort for understanding of the subject or problem. Barriers to this, are attitudes such as ‘It's not my job’ and ‘I'm not paid to know that’ are typical responses. Development of supportive teamwork and peer recognition can be powerful antidotes to overcome such resistance. Conversely, poorly devised reward systems and team structures reinforce the barriers.

Fig. 4.3 Stages of learning and the role of leadership. Source: Buckler (1996)

3 Understanding. Understanding develops as the depth of knowledge increases. Superficial understanding generally leads to single-loop learning, whereas double-loop learning requires much deeper understanding. Usually, commitment starts to develop as understanding rises. On the other hand, understanding may undermine the process if it starts to strongly challenge deeply held beliefs and values. This may lead to either overt or subconscious barriers in the move to commitment. Peter Senge calls this ‘creative tension’.

4 Commitment. Commitment cannot be achieved without intrinsic interest and curiosity. Without it the move to action is not likely to take place. For example, many training courses do not have the desired effect because they are not attended as a result of an intrinsic desire to learn but are imposed. Such desire cannot be directed, but must come from within the individual. It can, however, be nurtured and encouraged. To be most effective, learning at this level must be pulled by the individual not pushed by the organization. Unfortunately the barriers preventing the transition from commitment to enactment can be formidable because they typically require the individual to change behaviour. Often this is resisted by a powerful, in-built and unconscious defence mechanism. Argyris (1992) refers to such phenomena as ‘defensive reasoning’. Individuals need to develop a high level of self-awareness if this barrier is to be surmounted.

5 Enactment. It is only when individuals, working within teams, move to enactment that real improvements through learning start to emerge. However, this involves a degree of risk taking and the working environment must cater for risk-taking behaviour if it is to take place and benefits are to be gained. Development of an accommodating environment increases the probability of innovation and creative solutions to problems. The resulting energy for creativity is the true source of future competitive advantage. Effective discovery-learning systems can enable individuals to move very quickly to this stage. Revan's (1983) action learning concepts are based on this. Conversely tightly controlled environments can inhibit changes to processes and limit people's capacity to learn and improve. For instance, quality management standards such as BS 5750 and ISO 9000 can create a culture of ‘conformance’, where changes to processes and new ideas are discouraged, and would be criticized by auditing procedures.

6 Reflection. This is a key step in the learning process, and is the stage most often missing in ‘taught’ organizations. In this stage, actions, outcomes and theories are evaluated, and deep learning takes place. The compliant nature of ‘taught’ organizations, in which employees are taught the ways to perform process activities and then requested to conform to standards of operation, often means that individuals are not encouraged to question or challenge theories, and inappropriate actions continue to be taken long after those theories have been discredited. In extreme cases of ‘learning by rote’ the move to learning can be extremely difficult to overcome. If there is effective reflection, then with it comes increased understanding, which in turn increases commitment and action, and a virtuous cycle of learning is unleashed (Figure 4.4).

Role of leadership in creating a learning environment

Achieving the learning company vision depends greatly on the effectiveness of managers and team leaders in creating an environment where individual, team and, thereby, organizational learning is facilitated. In order to do this leaders have to build a deep understanding of the learning process, be able to identify an individual's position on the stages of the learning model, understand the driving and restraining forces applicable to the individual at that time and have intervention strategies to facilitate movement through the stages.

The role of leadership can be mapped on to the stages of learning mode. Leadership facilitates the move through the stages by:

Fig. 4.4 Virtuous cycle of learning

1 Questioning. The first step up the learning ladder is to move from a state of ignorance to being aware that an area of knowledge exists, and that it may be of benefit to both the individual and the organization. The leader will need to possess this insight and an enthusiasm and commitment to put it into practice. The leader's position as a role model is therefore vital in gaining the attention and interest of the team. Other team members may also have greater understanding, and can provide help as mentors and role models.

2 Developing shared vision and ownership. Developing a shared vision in a participative way with the team is a key requirement to move up the leader. This is, essentially, a two-stage process. Initially, when the understanding of the individual and team is brief the leader should concentrate on the ‘whats’ of the vision, and the role that learning will play in its achievement. As learning develops, the debate increasingly moves on to the ‘why’ areas. Facilitation of this process also starts to expose the barriers preventing movement up the learning ladder, and enables the leader to evolve his or her own understanding and to develop strategies to minimize their effects. The participative approach helps unlock intrinsic motivation by enabling individuals to satisfy their inner needs.

3 Enabling. To achieve something we must try doing that something. We can develop an understanding of preparing a meal from a recipe book, but until we try we will never be able to cook. Usually, however, the first few attempts involve a high risk of failure. The leader role at this stage is to provide opportunity and encouragement, and a cushion for failure, if benefits are to be achieved. Strategies must be devised to minimize risk, and ensure that failure does not prevent the individual from trying again. The more quickly individuals can be moved to the enactment stage, the more quickly experiential learning starts.

4 Removing barriers. Perhaps the most important role of the leader is to identify and circumvent the effects of barriers to learning. These barriers are present at each stage of the learning process, but become higher as one proceeds through the stages. The leader has to understand what might cause individuals to become ‘stuck’ on the ladder and develop an awareness of when and why this is happening. Individuals will not necessarily be aware of the high barriers, especially those which they themselves are operating within, and these will need to be drawn into conscious awareness before they can be managed. This is a very complex process and leaders will require a high degree of sensitivity and psychological understanding. Unfortunately, the level of sensitivity and understanding needed for this is very rare in most organizations.

Managing people towards knowledge climates and cultures

Despite the interest in the field of knowledge, much of the research evidence concerning management practices about knowledge cultures and creative climate remains unsystematic and anecdotal.

As mentioned earlier, the importance of culture has been emphasized by organizational theorists such as Burns and Stalker (1961) who present a case for organic structures as opposed to mechanistic structures. In popular thought there are many arguments that suggest that in order to facilitate innovation and knowledge-based learning, work environments must be simultaneously tight and loose. There appears to be a high dependency on knowledge with the development and maintenance of an appropriate context within which knowledge sharing can occur. The key distinguishing factor between companies that are successful in managing knowledge and those that are not is the ability of management to create a sense of community in the workplace. Highly successful companies behave as focused communities, whereas less successful companies behave more like traditional bureaucratic departments. Judge, Fryxell and Dooley (1997) suggest four managerial practices that influence the making of goal-directed communities: balanced autonomy, personalized recognition, an integrated socio-technical system and the availability of resources.

Balanced autonomy

Autonomy is defined as having control over means as well as the ends of one's work There are two types of autonomy:

- strategic autonomy: the freedom to set one's own agenda

- operational autonomy: the freedom to attack a problem, once it has been set by the organization, in ways that are determined by the individual himself or herself.

Operational autonomy encourages a sense of the individual and promotes entrepreneurial spirit, whereas strategic autonomy is concerned more with alignment with organizational goals. Firms that are most successful emphasize operational autonomy but retain strategic autonomy for top management. In these companies top management specify ultimate goals to be attained but thereafter provide freedom to allow individuals to be creative in the ways they achieve goals. The opposite approach, giving strategic autonomy, ultimately leads to lower strategic alignment. The result of strategic autonomy is an absence of guidelines and focus on effort. In contrast, having too little operational autonomy also has the effect of creating imbalance. Here the ‘road maps’ become too rigidly specified, and control drives out innovative flair leading eventually to bureaucratic atmospheres. What works best is a balance between operational and strategic autonomy.

Personalized recognition

Rewarding individuals for their contribution to the organization is widely used by successful corporations. Recognition can take many forms and there are common distinctions: rewards can be either extrinsic or intrinsic. Extrinsic rewards are those such as pay increases, bonuses and shares and stock options. Intrinsic rewards are those that are based on internal feelings of accomplishment by the recipient, e.g. being personally thanked by the president or CEO, being recognized by colleagues or being awarded an award or trophy.

Successful companies rely heavily on personalized intrinsic awards, both for individuals and groups. Less successful companies place almost exclusive emphasis on extrinsic awards. It would appear that when individuals are motivated more by intrinsic desires than extrinsic desires then there is greater sharing and transfer. Nevertheless, it has to be stated that extrinsic rewards have to be present at a base level in order to ensure that individuals are at least comfortable with their salary. Beyond the base salary thresholds it appears that learning and knowledge creation is primarily driven by self-esteem rather than external monetary rewards. Extrinsic rewards often yield only temporary compliance and can promote competitive behaviours which disrupt workplace relationships, inhibit openness and learning, discourage risk taking and can effectively undermine interest in work itself. Often, when extrinsic rewards are used, individuals tend to channel their energies in trying to obtain the extrinsic reward rather than unleash their creative potential.

Integrated socio-technical system

Highly successful companies appear to place equal emphasis on the technical side as on the social side of the organization. In other words, they look not only to nurture technical abilities and expertise but also to promote a sense of sharing and togetherness. Fostering group cohesiveness requires paying attention to the recruitment process to ensure social ‘fit’ beyond technical expertise, and also about carefully integrating new individuals through a well-designed socialization programme. Less successful firms seem more concerned with explicit, aggressive individual goals and tend to create an environment of independence, whereas successful sharers create a much more co-operative environment. Successful companies, meanwhile, appear to set much more reasonable goal expectations, and try not to overload individuals with projects. Too many projects spread effort too thinly, leading individuals to step from the surface of one to the next. These conditions create time pressures which militate strongly against sharing, learning and innovativeness.

Availability of resources

Organizational resources act as a cushion and help a company to adapt to internal and external pressures. Availability of sufficient resources correlates positively with knowledge sharing and learning. Indeed, it is not just the availability of resources but the availability of resources over time that appears to have a positive impact upon knowledge sharing and transfer. Less successful knowledge and learning programmes may possess ample resources but often these firms appear to have experienced significant disruptions or discontinuities in the availability of resources in the past or expect disruptions in the future. Therefore, knowledge programme success seems to be linked with both experience and expectations concerning availability of resources. The availability of resources, and future expectations of that availability, provide scope for the organization and its members to take risks that they would not do if they had few resources or anticipated interruptions in resource availability. Organizationally, this indicates the need for ensuring a basin of resources along a variety of critical dimensions (such as time, seed funding for new projects, etc.).

An individual who is given information cannot help but take responsibility’

(Jan Carlson, former Chairman, SAS Airlines)