6

Learning knowledge management

imperatives: present into future

We can currently observe increased requirements for better knowledge in the workplace to deliver competitive knowledge-intensive work. Demands have increased for customized and more sophisticated products and services. Globalization pressures have changed business worldwide. Nations which earlier supplied manual labour have started to compete with Europe, Japan and North America by offering competent intellectually based work. The Internet has given rise to knowledge workers across the globe who have access to the latest information, concepts, methodologies and so on. While access is still far from uniform and large groups of people in Africa, Asia and South America will probably have to wait a long time for it, there has been a noticeable shift in the pattern of work organization. In these changed circumstances, heralded by the Internet era, those that have become accustomed to be leaders will need to build and apply intellectual capital better – they increasingly must manage knowledge systematically. The expectations are that we stay at the tip of the iceberg of change.

In the age of knowledge

Peter Drucker made a passionate plea stressing the importance of knowledge, in suggesting that the only, or at least the most important, source of wealth in the contemporary society is knowledge and information (Drucker, 1993). Drucker notes three fundamental changes in knowledge during the twentieth century. First, there was the Industrial Revolution, in which knowledge was applied to tools, processes and products. Next, there was the productivity revolution when individuals like Frederick Taylor and Henry Ford began to apply knowledge to human labour. Finally, there is our present-day revolution in which knowledge is being applied to knowledge itself, namely the knowledge management and learning revolution.

This is not to say that the traditional production factors of land and labour are not important, only that they have changed in position and priority. According to Drucker, as long as there is knowledge, the other production factors are easy to obtain. Thus, the most important challenge of the knowledge-based economy is to find a methodology, a discipline or a process with which information can be made productive. This is the role that the knowledge management and learning initiates have come to fill.

Knowledge is not only widely seen as a key asset in companies. It is, at the same time, becoming the most important determinant of economic growth. Knowledge, embodied in human beings and in technology, has always been central to economic development. In recent times, however, it has gained higher prominence. Contemporary society is an information society and the contemporary economy is increasingly becoming knowledge-based. It is estimated that 50 per cent of the gross national product (GNP) of the largest European countries is knowledge-based (OECD, 1996). The most important source of wealth in the contemporary post-capitalist society is knowledge and information.

Demands of the knowledge-based economy

In this new world of knowledge-based economies, organizations increasingly have to deal with such matters as:

- increasing complexity of products and processes

- growing reservoir of relevant knowledge, both technical and non-technical

- increasing global competition coupled with shorter product life cycles, implying that learning processes have to be quicker

- an increased focus on the core competencies of the firm which have to be co-ordinated. This means concentrating on the few value-adding tasks and letting go less relevant ones

- increasingly flexible workforce, resulting in a mobile work-force, which makes holding on to knowledge and transferring knowledge all the more difficult (Uit Beijerse, 1999).

Benefits of knowledge management

The emergence of the above challenges prepared the ground to eventually usher in knowledge management and learning as one way for businesses to cope with the heightened complexity of the new world arena. Organizational success is determined by the interplay of many factors. Some are beyond influence or control while others are under the aegis of internal control. It is through the management and utilization of these factors that knowledge management yields corporate benefits. The type of benefits that can be derived by managing knowledge and learning are:

- improved efficiency

- improved market position by operating more intelligently on the market

- enhanced continuity of the company

- enhanced profitability of the company

- optimized interaction between product development and marketing

- improved relevant (group) competencies

- makes professionals learn more efficiently and more effectively

- provides a better foundation for making decisions like make or buy new knowledge and technology, alliances and merges

- improved communication between knowledge workers

- enhanced synergy between knowledge-workers

- ensures knowledge workers stay with the company

- makes the company focus on the core business and critical company knowledge.

Why knowledge management programmes are failing to produce bottom-line impact

Business challenges today are becoming more numerous, more threatening and more urgent. These challenges come in many guises: global competition, industry upheavals, e-technology and many more. It is imperative that firms respond to these with agility and acuity. Most of these challenges have forced companies to examine how they can leverage their knowledge capability base more effectively. Unfortunately, many of these responses have frequently failed to achieve the desired results.

Many millions of pounds are spent annually by companies venturing on to knowledge programmes. In light of large-scale investments; companies have anticipated large-scale improvements and bottom-line benefits. The evidence that is transpiring is rather mixed, especially in terms of bottom-line impact. Some companies have been very successful, while for many the experience has been rather more muted. This has fuelled a growing disquiet among some who have increasingly begun to question knowledge management and its supposed benefits.

Companies are increasingly unwilling and unable to devote attention and resources to directions unless they promise to deliver clear and important benefits. Hence, they now have begun to ask specific questions such as:

- Will knowledge management allow us to deliver higher bottom-line results?

- Will knowledge management make it possible to create more competitive products?

- Will knowledge management improve the effectiveness of our work?

- Will knowledge management reduce operating costs, allow us to be more responsive, improve our market image and otherwise become more successful?

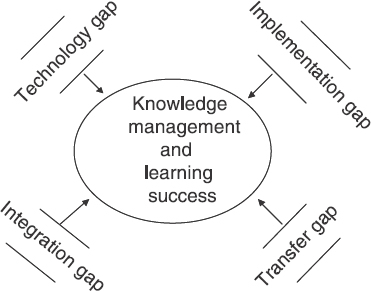

Knowledge management and learning programmes that are under-performing, in our view, have done so because they have failed to close four key gaps: the Technology gap, the Implementation gap, the Transfer gap and the Integration gap (TITI). Deficiencies in one or more areas result in companies’ knowledge management initiatives failing to deliver to expectations. We next deal with each of these gaps in turn (see Figure 6.1).

Gap 1: The technology gap (the delusion of high-tech high-touch)

Information technology has led many companies to envision a brave new world of leveraged knowledge. The Internet and intranets have made it possible for almost every employee to overcome time and location boundaries, and have enabled interaction among peers previously not imagined. Most companies have already rethought, or are beginning to rethink, how work gets done. They are linking people through electronic media so they can leverage each other's knowledge. While information technology has inspired this vision it cannot by itself bring the vision into being.

Fig. 6.1 The four gaps affecting knowledge management and learning performance

Human interaction

The fact is that despite the availability of technology, most companies still struggle to leverage knowledge. Virtual teams need to build a relationship before they can effectively begin to collaborate. This means they must develop a link and trust before e-communication. The most effective way of achieving this remains face-to-face interaction.

Deep insights

To make technology work requires changing people's work habits, which in turn lies in changing organizational culture. Knowledge sharing means getting people to take the time to articulate and share not just superficial insights but the deeper ones (Cross and Baird, 2000; McDermott, 1999). Unfortunately, deep insights are not very amenable to technological mining or distant and casual interaction. The fact is, if a group of people do not already share knowledge, do not already have plenty of contact, do not already understand what insights and information will be useful to each other, information technology is not likely to achieve it. Yet, most knowledge management efforts treat these cultural issues as secondary issues. The mainstay of attention is on information systems. That is, the tendency is to focus on identification of what information to capture, construction of taxonomies for organizing information, determination of who gets access, and so on. This big stumbling block in knowledge management is in simply using information management tools and concepts to totally drive the design knowledge management and learning systems.

Creative analogies

One way to explain why technological attempts to collect and codify the knowledge of the firm fall short is because they choke the process of creative analogy in thinking. Databases gather and store information through a process of abstraction and categorization. These systems perform by helping you locate what you are looking for, as long as you know what you are looking for. However, they play a limited role in the creative learning process, because if you know what you are looking for before you start, then the search may be necessary but the solution is in large part concluded. There is little chance for innovation because there is little chance of finding something better. Innovation occurs through finding connections that are not obvious between the current problem and past problems. For such knowledge creation to take hold, the search for new solutions to problems needs to take place in ways that allow, even encourage, unexpected analogy and connections to occur. This requires a mindset change to accompany the technology facilitation.

In summary, the strong technological bias of knowledge management has led to:

1 Creation of large information junkyards.

Example: A large company instructs its staff to document their key work processes in an electronic database. It turns out to be a hated task. Most staff feel their work is too varied to capture in a set of procedures. After being berated by senior managers they complete the task. Within a year the database is populated, but little used. It is too general and generic to be useful. The help they need to improve their work processes is not contained in it.

The result: an expensive and useless information junkyard. Creating an information system without an insight as to what knowledge people really need, or the form and level of detail they need works against leverage of knowledge.

2 Using technology without knowing and thinking. A fundamental duality in managing knowledge is between knowing and thinking. Knowledge always involves a person who knows, and thinking is key to making information useful. Together, they transform information into insights, insights into solutions, and solutions into action. This human ability to use information is the essence of knowledge management. Technology is a poor substitute for our thinking and knowing. Much of technological investment to date has been made with little regard to how knowing and thinking actually take place, and may need to take place in the future. Collection and storage are but small elements of the bigger knowledge equation.

Bridging the technology gap

McDermott asks what are the implications of these reflections on managing knowledge? Clearly, creating and leveraging knowledge involves much more than technology. It is, therefore, not surprising that e-linking people, documenting, and putting up fancy web sites is not enough to get people to think together, share insights they did not know they had or generate new knowledge.

Communities of practice

To overcome the limitations of technology we need to approach the creation and leverage of knowledge from a user perspective. We need to know something about those who will use the insights held in electronic repositories, the problems they are trying to solve, the level of detail they will need, perhaps even the style of thinking they use. One of the most effective ways to resolve this tension has been to change the focus from the unit of information/knowledge to the community that owns it, is likely to use it and develops it. Deploying technology to facilitate the user-developer community enhances the leverage of sharing. McDermott (1999) suggests a number of ways to achieve this:

1 Leverage knowledge, develop existing communities. Take care to develop natural knowledge communities. Formalizing communities of practice runs the danger of reducing the community to mere ‘tellers’ of the official story. Instead, nurture the communities by allowing them to tap into their own natural curiosity and energy to share knowledge. Build on the processes and systems they already use, and enhance the role of natural leaders.

2 Focus the communities on knowledge that is important both to the business and the members. Essential information that can add value should be identified so resources can be channelled efficiently and effectively.

3 Create regular forums for the community to think about and share knowledge about specific problems. Knowledge management processes should include systems for sharing information and forum events for thinking. The events, whether face to face, by telephone, electronic or written, need to spark collaborative thinking, not just make static presentations of ideas.

4 Let the community decide what to share and how to share it. Allow communities to own the knowledge, then the community can organize, maintain and distribute it to members. This is a key role of community co-ordinators or core group members. Influential members may use their knowledge of the discipline to judge what is important, ground breaking and useful, and may enrich information by summarizing, combining, contrasting and integrating it.

5 Create a community support structure. Communities are held together by people who care about it. Communities need support in the form of resources, time and effort if they are to survive. Also, without an individual or small group taking on the job of holding the community together, keeping people informed of what others are doing and creating opportunities for people to get together to share ideas, the community withers and dies.

6 Use information technology to support communities, not vice versa. Many have fallen into the trap of thinking that the role of communities is to create knowledge so that it can be posted up on the electronic database. Remember, pasting knowledge on to an electronic board is a side outcome not the main goal. The main aim of communities should be to create useful knowledge.

7 Use the community's terms for organizing knowledge. Organize information naturally. The key to making information easy to find is to organize it according to a scheme that tells a story about the discipline in the language of the discipline. A taxonomy should, like a map, help people to navigate around the e-repository.

8 Integrate learning communities into the natural flow of work. Community members need to ‘connect’ in many ways. In the natural work environment, work gets done through social discourse not just through constant problem solving. Blend the informal with the formal to get the most out of community members – just as they would if they were informally networking elsewhere.

9 Treat culture change as a community issue. Learning communities thrive in sharing cultures. More than this, they themselves can be used as vehicles for creating a culture of sharing. Measurement metrics, policies and rewards to support sharing knowledge all help the transition toward a sharing culture but the key shift is likely to be within the mindset of the communities.

With the knowledge imperative already arrived at the corporate doorstep many have responded speedily but mistakenly. They have in their misguided efforts set technology at the heart of managing knowledge. The knowledge revolution may have been inspired by new information systems, but it takes human systems to realize it. This is not because of a reluctance on the part of people to use information technology. It is because knowledge involves thinking with information. By simply increasing the circulation of information, we address only one of the components of knowledge. To really use knowledge we need to enhance both thinking and information. In the corporate world, a natural way is to build communities of practice that cross teams, disciplines, time, space and business units.

McDermott (1999) defines four key challenges in building these communities:

1 The technical challenge: to design human and information systems that not only make information available, but help community members think together.

2 The social challenge: to develop communities that share knowledge and still maintain enough diversity of thought to encourage thinking rather than sophisticated copying.

3 The management challenge: to create an environment that truly values sharing knowledge.

4 The personal challenge: to be open to the ideas of others, willing to share ideas and to maintain a thirst for new knowledge.

By melding human systems with information systems, companies can build a capacity for learning broader than the learning capacity of any single individual within it.

Gap 2: The Implementation gap (the illusion of doing without doing)

One reason for knowledge management's underperformance is that there is a gap between what the company thinks and what it does, and between what the company knows and what it does. Although many companies know about knowledge creation, benchmarking, knowledge management and their importance in theory, there nevertheless continues to be a vast gap in transforming this knowledge into organizational action. Only through organizational action can performance be generated.

Bridging the implementation gap

There is increasing recognition that many firms have gaps between what they know and what they do, but the causes have not been fully understood. Pfeffer and Sutton (1999) note the knowing-doing gap arises from a number of factors and it is essential that managers understand them. They find some recurring themes that may help us understand the source of the problem and, by extension, some ways of addressing it:

1 Putting ‘why’ before ‘how’: forgetting philosophy is important. Most managers want to learn ‘how’ in terms of detailed practices and behaviours and techniques. Unfortunately, even managers espousing knowledge and learning forget the more transcendental question (the one that leads to double learning) of asking ‘why’.

Example: Why has it been so difficult for a company to copy another's best practices, even though extensive details can be found in books or many benchmarking tours have been undertaken? Because visitors on tours see the visible arte-facts (the machinery, the layout, the papers and documents) but do not sense the soul. Most best practices are based on philosophy and perspective, about such things as people, processes, quality and continuous improvement, not just on a set of techniques or practices.

What is important is not so much what we do (the minute specifics of what we do, how we manage, what techniques we employ) but why we do and why we use what we use. It is the underlying philosophy and view of people within the business that provides a foundation and context for the practices. It is this foundation and context which play a large part in success or failure. Just copying external practices and techniques is akin to focusing on the explicit. Not appreciating the underlying philosophy and logic (the tacit aspect of management itself) leads to an imbalanced focus on the explicit aspects of knowledge management. Without the tacit knowledge about the knowledge management initiative, the explicit is at best a diversion from the where and the how that companies should be focusing their attention on.

2 Knowing comes from doing and teaching others how. In a world of full of theory it is easy to forget that one fundamental tenet of learning is ‘knowing by doing’. Knowing by doing develops a deeper and more profound level of knowledge, and almost by definition helps to eliminate the knowing-doing gap.

3 Action counts more than elegant plans and concepts. In a world where sounding smart has too often come to be a substitute for doing something smart, there is a tendency to let planning, decision making, meetings and talk become a substitute for implementation. Many people in modern businesses have achieved their high positions through words not deeds. In such a world, it seems, we have come to believe that just because we have debated a point, or even made a decision, that something will happen. Most of us know this is far from the case.

4 There is no doing without making mistakes. In attempts to make things happen, one must be prepared to make mistakes. This is the culture characteristic of action. Even excellent plans run the risk of failure. The important question is, how does the company respond? Does it provide ‘soft landings’ or does it treat failure and error so harshly that people are encouraged to engage in perpetual analysis, discussion and meetings just to avoid doing anything because they are afraid to fail? There is a wonderful story concerning this, about Thomas Watson Sr, IBM's founder and CEO for many decades:

A promising junior executive at IBM was involved in a risky venture for the company and managed to lose over $10 million in the gamble. It was a disaster. When Watson called the nervous executive into his office, the young man blurted out, ‘I guess you want my resignation?’ Watson said, ‘You can't be serious. We just spent $10 million dollars educating you!’

5 Fear fosters knowing-doing gaps. Closely associated with the above is a mentality of fear that pervades many companies. Pressure and fear make employees behave in seemingly strange ways – ways that their close friends and family would not recognize. Yet, the reality is that no one is going to try something new if the reward is likely to be a career disaster. Fear-culture companies are typified by comments such as: ‘we may not be doing very well, but at least our performance is predictable’; ‘no one has gotten fired for doing what we're doing. So, why should we try something new that has risk involved?’

Firms that are able to drive out fear are better able to turn knowledge into action. They do not go on errands of apportioning blame but rather, attempt to build cultures in which even the concept of failure becomes almost irrelevant. Such companies put people first and act as if they really care about their people. Successful knowledge management companies are characterized by leaders who inspire respect, affection and admiration, but not fear. The fear orientation is a mental tone which is set in swing from the very top. L. DeSimone, 3M's CEO, renowned for its risk-accommodating culture once noted: ‘We don't find it useful to look at things in terms of success or failure. Even if an idea isn't successful initially, we can learn from it.’

6 Measure what matters and what can help turn knowledge into action. The often voiced dictum ‘what is measured is what gets done’ has led many companies to the apparent belief that the more things they measure, the more they will get done. Unfortunately, this is not the case. A few measures that are directed at critical process outcomes are better than a plethora of measures that only serve to produce a lack of focus and confusion about what is important and what is not.

Sadly, many companies have blindly followed what could have been good advice to produce countless metric and measures. The situation has been compounded by the ready availability of computers which make data capture and analysis so easy, tempting them to fall into the conundrum between the thirst for information, which drives many measurement initiatives, and informed wisdom that drives knowledge into action.

7 What leaders do, how they spend their time and how they allocate resources matter. What differentiates a successful company from one not so successful is not that one possesses more intelligent or nicer people. The differentiating factor lies in the systems and the day-to-day management practices that create and embody a culture that values not just the creation of knowledge, but also of using that knowledge. Good leaders know that their job is not to know everything and decide everything, but rather to create an environment in which there are lots of people who both know and act. Good leaders create environments, reinforce norms and help set expectations through what they do, not just their words.

8 Knowing about the knowing-doing gap is not enough. Knowing about the knowing-doing gap is different from doing something about it. Understanding root causes is helpful because it can guide action but, in itself, this knowing is very deficient – only implementating action makes performance!

Gap 3: the transfer gap (ignorance into blindness)

Best-practice transfer

Many companies invest a lot of energy in creating knowledge and developing best practices by dint of their own effort or via benchmarking. Yet, once identified or developed, most find they are frustrated by their inability to identify or transfer outstanding practices from one part of the company to another. Even possessing superior practices and processes and armed with irrefutable evidence, companies continue to observe their operating units repeat mistakes, reinvent the same practices and processes or simply ignore them.

One would expect that superior practices would spread like wildfire throughout a corporation but it seems they do not. One Malcolm Baldrige Prize winner is supposed to have said: ‘We can have two plants right across the street from one another, and it's the damnedest thing to get them to transfer best practices.’

Carla O'Dell (O'Dell and Grayson, 1998) reports that a study in 1994, sponsored by the American Productivity and Quality Center (APQC), by the researcher Gabriel Szulanski, attempted to understand what prevents the transfer of practices across a company. The study found that best practices could lie undetected for years before being discovered. Even after discovery, it took more than two years on average before other sites began actively trying to adopt the practice, if at all. Szulanski questioned why knowledge and practices did not transfer. According to the study, it was not because people are inherently turf-protecting, knowledge-hoarding beings. Szulanski (1996) found:

1 The biggest barrier to the transfer was ignorance at both ends of the transfer. Often, neither the ‘source’ nor the ‘recipient’ knew someone else had knowledge they required or would be interested in knowledge they had.

2 The second biggest barrier to transfer was the absorptive capacity of the recipient – even if a manager knew about the better practice, he or she might not have the resources (time or money) nor sufficient practical detail to implement it.

3 The third biggest barrier to transfer was the lack of a relationship between the source and the recipient of knowledge, i.e. the absence of a personal link, credible and strong enough to justify listening to or helping each other, stood in the way of transfer.

4 Even in the best of firms, in-house best practices took an average of twenty-seven months to wind their way from one part of the organization to another.

O'Dell goes on to note that most people have a natural desire to learn, to share what they know, and to make things better. This natural desire is thwarted by numerous obstacles:

1 Organizational structures that promote ‘silo’ behaviour, in which people, divisions, and functions are so preoccupied with optimizing their own narrow accomplishments and rewards that they, consciously or unconsciously, hoard information and thereby suboptimize the total organization.

2 Cultures valuing personal technical expertise and knowledge creation over knowledge sharing. Another cultural blinker is the prevalence of the ‘not-invented-here’ syndrome and the lack of experience in learning from outside one's own small group.

3 The lack of contact, relationships and common perspectives among people who do not work side by side. In a great many companies, the left hand not only does not know what the right hand is doing, but it also may not even know there is a right hand.

4 An overreliance on transmitting ‘explicit’ rather than ‘tacit’ information. The obsession of simply creating databases does not cause knowledge management.

5 Not allowing or rewarding people for taking the time to learn and share and help each other outside their own small corporate village. For most people, demands upon time are enormous and, unless capturing and sharing information are built into the work processes, sharing does not happen.

O’ Dell (O'Dell aad Grayson, 1998) proposes seven lessons to improve transfer of best-practices:

1 Use benchmarking to create a sense of urgency or find a compelling reason to change.

2 Focus initial efforts on critical business issues that have high payoff. Concentrate your energies on the few projects that are likely to improve long-term capabilities. You do not get many opportunities to demonstrate success.

3 Make sure that every ‘plane’ you allow to take off has a ‘runway’ available for landing. In the initial energy burst that comes from imagining the improvements and gains possible from the transfer of best practices, there is a tendency to forget that an organization can only invest in and support a finite amount of change at any one time. It is demotivating to create or find a best practice, only later to discover the company does not have the resources to implement your improvement idea.

4 Do not let measurement get in the way. Rather than measure everything that moves, measure that which matters. ‘Paralysis by analysis’ is an easy pitfall to fall into.

5 Change the reward system to encourage sharing and transfer. Real internal transfer is a people-to-people process and usually requires enlightened behaviour. Leadership can help by:

(a) promoting, recognizing, and rewarding people who model sharing behaviour, as well as those who adopt best practices

(b) designing approaches that reward collective improvement as well as individual contributions of time, talent and expertise

(c) reinforcing the need for people at all levels to take responsibility for participating in the activity of sharing and leveraging knowledge

(d) asking regularly what people are learning from others and how have they shared with management ideas they think worthy

(e) supporting teams that invest or ‘sacrifice’ resources to make this sharing happen, especially if they themselves do not directly benefit.

6 Use technology as a catalyst to support networks and the internal search for best practices, but do not rely on it as a solution.

7 Leaders need to consistently and constantly spread the message of sharing and leveraging knowledge for the greater good. The most effective transfer processes are pull driven (the demand to learn and change comes from the person that has a problem or need) rather than push (if you let them know about it, they will seek it out) approaches. Leaders can encourage this by developing success stories, providing infrastructure and support, and devising a reward system to remove barriers.

Gap 4: the integration gap (Humpty-Dumpty fell off the wall)

The final reason for failure to perform to expectations rests in the integration gap. It may be that firms have not made any obvious mistakes neither are their knowledge and learning efforts inappropriate. Instead, the problems may arise because the efforts have not been be integrated in a cohesive manner. Few knowledge programmes examine how the company's sum of capabilities must fit together. Indeed, in an age when capabilities are generally accepted to be the backbone of sustainable competitive advantage, integration is one key capability that remains underused (Fuchs et al., 2000).

Strategic fit

Successful knowledge and learning companies are able to address competitive challenges not because they excel at any one thing, but because they so effectively integrate the parts of the process into a strategic whole. In this sense, integration recalls a symphony orchestra. An orchestra demands at least three things to render a fine performance:

- a comprehensive complement of talented musicians (individual capability)

- an ability to play as a perfectly aligned unit (team capability)

- an emphasis on the right musicians for the right compositions (strategic capability).

In the knowledge and learning context, firms must understand not just a few but all of the key elements of knowledge creation and exploitation strategy, and they must master many of them. They must also carefully align these elements (people, culture, process and technology) to maximize their complementarity with one another and with the environment.

Strategic integration, Fuchs et al. (2000) indicate, demands the same qualities of the organization as it does from the orchestra: comprehensiveness, alignment, thematic emphasis and communication:

1 Comprehensiveness. Integration begins with a clear notion of what needs to be integrated. This demands a comprehensive understanding of all the knowledge elements the firm must use to compete effectively. Success in knowledge management is not just about thinking, posturing and talking about what to do or even taking action. It demands both: the complement of thought with action.

2 Alignment: making the jigsaw fit. Success in knowledge management is not arrived at by piecemeal and ad hoc implementation of a random set of mechanisms or processes. It is brought about by putting into place pieces that reinforce each other – pieces that work through synergy and linkages, which when aligned together magnify the power of the punch. What is most important is not just knowledge management's individual parts but, rather, how they aggregate and align to address the challenges and opportunities in the external environment.

3 Focus. Alignment occurs not just from identification of the mix of projects and themes to emphasize, but also from selecting the critical ones to emphasize above others. This is so because at any one time it is possible for a company to invest resources in only a few projects and themes. Trying to follow all results in a thin spread, which more often then not is a recipe for failure.

4 Communication. To make knowledge management work, managers must put everyone in the big picture. Companies can do this by communicating frequently, clearly and with force of intent. Communication can, and should, be many different reinforcing channels, such as policy documents, speeches, newsletters, bulletin boards and symbolic rituals. Usually, however, strategic priorities are best communicated when words are followed by reinforcing actions captured in the form of hard decisions and policies, and by instituting sharing-led reward and accountability systems.

In summary, the process of building a knowledge and learning organization is a dynamic, relentless and iterative one. It demands continual effort by many managers to generate and exploit the knowledge capabilities in an ever-changing world. As the business environment fluxes, the organization must evolve. Managers of highly successful organizations constantly reinforce and revitalize the company's strategic intent by ensuring that the pieces dovetail to form the big picture. Knowledge programmes succeed not so much because they have some brilliant and complex magical potion, but because they harmoniously blend and combine knowledge activities and processes.

Looking into the future: a scenario of knowledge management developments ahead

Since many companies have embarked on the road towards knowledge and learning it is important to take a moment and imagine what may lie ahead. There are many views on this but one comprehensive forecast is presented by Wiig (1999). He suggests a number of developments in knowledge development in coming years:

1 There will be a strong push away from ‘knowledge is actionable information’ to a ‘knowledge is understanding’ perspective. Other traditional and narrow perspectives will also be displaced by richer cognitively based paradigms. Insights from emerging cognitive research appear to be very helpful in expounding what and how people can handle complex challenges competently.

2 Future knowledge management practices and methods will be systematic, explicit and relatively dependent upon advanced technology in several areas. However, there will be a move towards more people-centric knowledge management. This will occur as a result of growing recognition that it is networking and collaboration that forms the basis for the knowledge-sharing behaviours.

3 By building upon the knowledge management experiences of other companies, the manner in which knowledge management is organized, supported and facilitated will change:

(a) Obvious structural changes will be associated with who leads the knowledge management programmes. Two polarities are likely to emerge: either a high-level chief knowledge officer (CKO) or distributed effort at mid-organization level.

(b) Changes that deal with reorganization of work and the abolishing of whole departments that are integrated into other operations will be less apparent but prevalent.

4 Management and operating practices will change to facilitate knowledge management in many ways:

(a) Incentives will be introduced to promote innovation, effective knowledge exchange (sharing), learning and application of best practices in all work situations

(b) Cultural drivers such as management emphasis and personal behaviours will be changed to create environments of trust, and focus will be on finding root causes of problems without assigning blame.

5 Knowledge management perspectives will become deeply embedded within regular activities throughout the corporation.

6 New practices will focus on desired combinations of understanding, knowledge, skills and attitudes when assembling work teams or analysing requirements for performing work. The emphasis on complementary work teams will coincide with the movement towards virtual organizations, where many participants will be external workers who are brought in for limited periods to complement in-house competencies for specific tasks.

7 Most organizations will create effective approaches to transfer personal knowledge to structural intellectual capital (SIC). Increased transfer will allow better utilization and leveraging of the SICs. This will also have a positive side effect for external subject-matter experts who may be able to provide, i.e. sell, their expertise to many enterprises for continued use. This can already be observed in isolated instances, e.g. with refinery operations experts.

8 More comprehensive and broader approaches to knowledge management practice will become the norm. For example, designing and implementing comprehensive multimode knowledge transfer programmes will be common. Such programmes will take systematic approaches to integrate all primary knowledge-related functions including:

(a) major internal and external knowledge sources

(b) major knowledge transformation functions and repositories such as capture and codification functions and computer-based knowledge bases

(c) major knowledge deployment functions such as training and educational programs, expert networks, knowledge-based systems, etc.

(d) different knowledge applications or value-realization functions where work is performed or knowledge assets are sold, leased, or licensed.

9 Education and knowledge support capabilities such as expert networks or performance support systems will be matched to cognitive and learning styles, and to dominant intelligences. This will facilitate workers, particularly full-time employees, in all areas to perform more effectively. In addition, new, powerful, and highly effective approaches to elicitation and transfer of deep knowledge will be introduced. Such capabilities will allow experts to communicate understandings and concepts and will facilitate building corresponding concepts, associations and mental models by other practitioners.

10 One area of considerable value will be the development of comprehensive and integrated processes for knowledge development, capture, transformation, transfer and application.

11 Knowledge management will be supported by many artificial intelligence developments, some of which are:

(a) intelligent agents

(b) natural language understanding and natural language processing

(c) reasoning strategies

(d) new knowledge representations and new forms of ontology.

12 Information technology will continue to progress and will bring considerable change to many knowledge management areas. These will include:

(a) ‘portable offices’ that roam anywhere with their owners

(b) communication-handling systems that organize, abstract, prioritize, make sense of and, in many instances, answer incoming communications

(c) intelligent agents that not only will acquire desired and relevant information and knowledge, but will reason with in relation to the situation at hand.

In order to create broad and integrated capabilities, most of the changes introduced by these developments will not be able to stand alone, but will be partly combined with other changes, many of which are likely to have focuses other than knowledge management.

Organizational gains from futuristic advances and developments

There are many expectations for strategic, tactical and operational improvements from the pursuit of knowledge management. Practical experiences of leading-edge companies indicate that benefits can be substantial. However, thus far, most direct benefits have been operational. Strategic benefits by nature are much more indirect and take longer to realize. Nevertheless, it is because companies hope they will obtain strategic benefits that they actively follow knowledge management programmes. In the future, the scenario will exhibit more strongly many of the reflexes that are already taking shape – namely, an increasing trend to pursue strategically oriented revenue enhancement instead of the early search for ‘low-hanging fruits’ of operational improvements. Wiig (1999) provides illustrative examples of strategic, tactical and operational benefits.

Strategic benefits

1 Increasing competence to provide improved value-added delivery of products and services, encapsulated with higher knowledge content than previously possible. This may be achieved by:

(a) having knowledge workers who possess and have access to better applicable knowledge

(b) organizing work to facilitate application of best knowledge.

2 Greater market penetration and competitiveness.

3 Broadening of the capability to create and deliver new products and services and a greater capacity to deliver products and services to new markets.

Tactical benefits

1 Faster organizational and personal learning by better capture, retention and use of innovations, new knowledge and knowledge from others and from external sources, achieved by:

(a) more effective knowledge transfer methods between knowledge workers

(b) more effective discovery of knowledge through Knowledge Development Directory (KDD) and other systematic methods

(c) easier access to intellectual capital assets

(d) more effective approaches to ascend Nonaka's knowledge spiral by transforming tacit personal knowledge into shared knowledge.

2 Lower loss of knowledge through attrition or personnel reassignments achieved by:

(a) effective capture of routine and operational knowledge from departing personnel

(b) assembly of harvested knowledge in corporate memories that are easy to access and navigate, and can be expected to lead to a greater ability to build on prior expertise and deep understanding.

3 More knowledge workers will have effective possession of, and access to, relevant expertise in the forms of operational knowledge, scripts and schemata.

4 Employees will obtain greater understanding of how their personal goals coincide with the enterprise's goals.

Operational benefits

1 Employees will have access to, and be able to apply, better knowledge at points of action. This will be achieved by, for example:

(a) educating employees in the principles of their work (via scripts, schemata and abstract mental models)

(b) providing knowledge workers with aids to complement their own knowledge

(c) training knowledge workers to operationalize abstract knowledge to match the requirements of the practical situations they deal with.

These changes can be expected to lead to lower operating costs caused by fewer mistakes, faster work, less need for hand-offs, an ability to compensate for unexpected variations in the work task and improved innovation.

2 Operational areas will experience less rework and fewer operational errors.

3 The enterprise will achieve greater reuse of knowledge.

To attain the above benefits, companies will have to undergo noticeable change within themselves. For instance, the developments will influence the culture to promote greater initiatives and greater job satisfaction among employees. These effects are likely to transform the workplace.

The changing workplace

As noted above, shifts emanating from knowledge-led initiatives are likely to change the workplace, both visibly and and less so. The less visible changes will, perhaps, be more significant since many will involve the way people work with their minds. The changes that people will experience in the workplace include:

1 Greater emphasis on interdisciplinary teams, with focus on using profiles of best mix of competencies for specific projects at hand.

2 A major change in the workplace, resulting from the increasingly temporary nature of many employment situations. This will lead to:

(a) greater emphasis on assembling short-lived teams with requisite knowledge profiles to address specific tasks

(b) people having reduced allegiances to the temporary employer

(c) increased efforts by individuals to improve their expertise to maintain and enhance personal competitiveness.

3 Greater reliance on conceptual knowledge to guide the direction of work.

4 Better understanding by individual knowledge workers of how they can influence implementation of company strategy by each small decision or act that is part of their daily work.

5 Greater degree of collaboration and willingness to co-ordinate and co-operate with associates and other activities.

6 Increased personal understanding by employees of how they personally benefit from delivering effective work.

7 Greater job security and less hesitation and procrastination to undertake complex tasks after they build increased metaknowledge and professional experience or craft knowledge about the work for which they are responsible.

8 Increased reliance on automated intelligent reasoning to support work.

9 Intelligent agents, deployed internally and externally, will offload ‘data detective work’ required to locate and evaluate information required in many knowledge work situations, ranging from plant operators to ad hoc strategic task forces.

10 New organization of the physical work environment will change the way people work together and allow greater richness of interaction. The new work environments will be designed to foster knowledge transfer and exchange through networking and collaboration, and will facilitate serendipitous innovations.

In aggregate, it can be expected that knowledge management will allow companies to expend less effort to deliver present-day outcomes or with the same effort better products, services and revenues.

The knowledge business and the knowledge marketplace

The impact of the developments will not be confined to organizations but will have ramifications in the wider community. For instance, the developments are likely to transform the business of knowledge and its market. Already, we are witnessing such change with the advent of more companies moving from the traditional role of manufacturer or service provider into the role of advice and consultancy provider. For example, Lotus, the car maker, reportedly receives greater revenues from advising other car makers on building engines than it receives from selling its own products. Electronic advisory or consulting services is also fast emerging. Over time, we are likely to see single individuals with all kinds of expertise, which they sell in the marketplace. Individuals, as free agents to virtual corporations, will be able to trade their knowledge in ways that at present we can barely glimpse.

A societal impact

There will be many consequences for society – both positive and negative. Positively, knowledge discovery processes will provide powerful insights into preferences and behaviours of the consumers and allow companies to better meet their needs. Negatively, there may, because of more advanced communication and connection, be a greater number of deliberate misrepresentations by avaricious companies and individuals playing on the ignorance of the young and naïve.

What might all this mean?

All these developments suggest we are evolving from one stage to another. We are being carried by one grand set of challenges to another, sometimes knowingly, sometimes unknowingly, at times deliberately and at other times by events beyond our control or the control of others. To repeat the old saying ‘the only constant is change’. We next take a peek into the future and examine the broader picture for what lies there.

Stages of organization development: past into the future

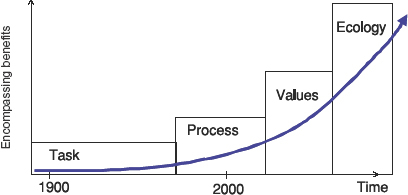

Being at the start of the millennium is an auspicious time to consider where we have come from and where we are going in the management of organizations. To help sense the trajectory of development we present a stage-based model, as described in Harung, Heaton and Alexander (1999). In this model, a stage constitutes a qualitative advance involving a new mode of knowing which allows solutions to be found to problems inherent in the prior stage of development. Thus, more advanced stages of corporate development entail increasingly adaptive and effective management thought and behaviour. In this stage-based evolution, it is necessary at the outset to note that not all companies are at the same developmental position. Some are further ahead then others. In the evolutionary trajectory, four distinct progressive stages can be discerned: task, process, values and ecology. These are depicted in Figure 6.2.

The first stage of organization development is task based. All companies, at all stages, carry out tasks but the manner in which they are executed is different. At this first stage, awareness is predominantly concerned with performing isolated, concrete tasks. Task-based management is the most common stage in today's organizations. The second stage, process based, is becoming increasingly evident and is characterized by the integration of all activities and tasks into an interlinked system. Processes overlay tasks; they inform us of the flow through which tasks are performed. The third stage of organization development is values based. Values tell us why to undertake the process. They give a direction to the process. In this stage managers employ intrinsic motivation; the sense of feelings in eliciting judgements of right and wrong and through shared values align the corporation towards its aims. The fourth stage is ecological based. This stage of evolution encompasses an holistic approach, in which the company is harmoniously synchronized with its natural habitat and wider society.

Fig. 6.2 Stages in business organization evolution

Stage 1: Task-based management

Companies at this stage operate isolated tasks through centralized formal authority. Work is hierarchical, functional and broken down into discrete simple tasks with each worker performing one or at most a few repeatable functions. The assumption is that only a few people at the top of the hierarchy know what needs to be done and how it can be done. Through command and control those in authority make certain that employees adhere to procedural power. In this stage, two types of task-based management styles may transpire: autocratic management or bureaucracy.

Autocratic management appears when there is a belief that employees are capable only of following rules, but have not the intellect to generate new rules in accordance with abstract principles or organizational goals. In this scenario, the managers create a rule for every contingency, and lines of reporting and authority are clearly drawn. Bureaucratic organization, while possessing many of the characteristics of task organization, increases the likelihood of producing consistency of actions, but this consistency is at the behest of governance through strict adherence to procedures and rigid rules. These features place the organization in a straitjacket, unable to change with the arrival of opportunities and threats.

A task-based organization adopts a negative view of the intrinsic capabilities of people, in making the implicit assumption that there is a need for extensive control external to the individual. Additionally, since each task is considered in isolation, work tends to be boring and meaningless. Today, more employees want to express their intrinsic intelligence and pursue something that each considers meaningful. Because of changes in manufacturing from simple to complex goods, it is virtually impossible for management alone to co-ordinate all the isolated tasks in a complex process. In modern society, knowledge and service workers are becoming the norm. In these environments, the task-based style of management is either beginning to crack at the seams or it simply does not work anymore. This leads to the second stage of organization evolution.

Stage 2: Process-based management

In process-based organizations, there is a shift in focus from isolated tasks to streams of related activities involving many different functional departments. Characteristically, the work is centred on teams, enjoying varying degrees of autonomy. Employees in the company participate in the improvement of processes, i.e. they make decisions to improve processes and assess the outcomes, and even evaluate their own performance. Compared with task-based management, process-organization features substantially higher levels of competence and collaboration. Participation in decision making necessitates having and sharing greater amount of information. Hence, sharing information is central in process-based businesses.

Process-based management does not do away with control. Rather, each team or members exercise greater self-control. When it works, this inner locus of control is continuous, simpler, more direct and more dignified. Self-motivated individuals do well in process-based environments. Also, because of greater devolved decision making, a greater proportion of employees will need an enhanced set of competences to operate effectively.

Process-based management requires that the typical member of the organization more fully utilizes his or her intellect. In these environments work becomes more satisfying because people have a greater sense of accomplishment from their contributions. In outcomes terms, process-based management results in achieving more with less effort.

Stage 3: Values-based management

According to dictionary definitions, values are defined as one's principles, standards, or judgement of what is valuable or important in life. The idea behind values-led organizations is that if the company's values are sound and widely accepted then employees will, for the most part, be fully capable of organizing their activities themselves as self-managing teams or units. In this situation, the role of managers is to encourage productive values throughout the organization. In a values-based organization, the ability to receive and give trust will be high. Managers will focus on nurturing the feelings and sense of identity of their employees. Collins and Porras (1994) capture the ideals of values-led organizations in expressing the sentiment:

the crucial variable is not the content of a company's ideology, but how deeply it believes its ideology and how consistently it lives, breathes, and expresses it in all that it does. It may be that socially imposed values, combined perhaps with fear of punishment or loss of face, can create an artificial management by values on a temporary basis. However, on the whole, the only way psychological ownership of sound human values can be accomplished on a sustainable basis is in an organization in which individuals have strong, individuated self-identities.

(Collins and Porras, 1994)

Giving genuine freedom and trust to employees who are developed enough to accept and use it, enhances innovation and increases the diversity of opinions. Immature companies, which lack the ability to handle diversity, will tend to perceive the situation threateningly. In contrast, values-based companies foster and enjoy unity in diversity. The paradox, of course, is the greater the diversity, the greater the need for unity. For this reason, a strong sense of common vision and purpose is essential for these companies. Fortunately, self-actualized people are predisposed towards win-win interpersonal strategies (as opposed to win-lose) and often possess the ability to simultaneously satisfy individual and collective needs. In such companies, superficial role-playing and the manipulation of others are likely to diminish with the general increase in personal integrity. The question is, how many companies today have reached the stage of values-based organization? While opinions may differ, it is more than probable that only a handful exist.

Stage 4: Ecological-based organization

There is an emerging perspective in management which is beginning to appreciate that an organization is inherently a part of the self-organizing universe, of which man is an integral part. The implicate order is of holistic intelligence, which is interconnected in nature with everything (Bohm, 1980). By stimulating the deeper levels of curiosity and creativity, and awakening the best drives within us, businesses can become the agents of flow to the natural order, rather than prospectors wishing to impose control over nature. This is the ‘being’ of the ecological organization. The ecological organization binds and harmonizes itself and people to nature. It is characterized by principles such as:

- harmony with the natural environment

- efficiency on a par with nature's ‘principle of least action’

- spontaneous and frictionless co-ordination

- creative inspiration akin to artistic genius

- doing well by doing good: prosperity and social value

- spontaneous change in an evolutionary direction

- leadership which promotes full human development.

In this emerging view, organizing is not an act of dominion over the environment; rather, it is a reflection of innate processes of natural systemic order.

Where are knowledge and learning companies on this continuum?

The answer to this question is best answered by a brief reiteration of the chief characteristics defining such companies. Present-day knowledge and learning companies are characterized by:

1 Systematic process approach. The knowledge and learning orientation requires a minimum of control and direction to be effective. Nevertheless, it must be constructed in a systematic manner to engender individual, team and organizational learning. This demands defining and managing through a clear and accountable knowledge and learning process-based system.

2 Leadership. A participative leadership style with a high level of facilitation and coaching skills is the most appropriate for the management of knowledge organizations. Leadership behaviours that stifle learning are identified and avoided.

3 The team. Flatter structures, with fewer tiers of management and greater empowerment of teams, are a feature of the current knowledge organization. These structures have changed the way people work and support each other. Support for effective teamworking has moved from a directive role to a facilitating role. Additionally, the greater responsibility placed on team members has meant that they need to be supported by team-building and group-learning activities. Enhanced competencies are much needed to make possible the seamless switching that is needed in moving continuously from a knowledge creation mode to a knowledge exploitation mode.

4 The individual. Support for individual learning commonly arises in the form of coaching and mentoring. There is also a general provision to assist with self-managed learning, over and beyond formal training to build employee competencies. The emphasis is on identifying and removing barriers to learning, and allowing individuals sufficient freedom to maintain high levels of intrinsic motivation. At the same time, individual activities are process aligned to business objectives.

5 Technology systems. Recent developments in computer systems present many new opportunities to develop and use knowledge. Knowledge and learning are facilitated through efficient and effective collection, storage and retrieval systems. Information technology developments have enabled expansion of learning possibilities. This is especially the case if technological solutions have been designed with the end-users in mind.

6 Culture and environment. Knowledge management and learning requires that opportunities for individuals and teams to experiment are maximized. This has led many companies to attempt installing creative inquiry attitudes in employee approaches to problem solving. This has involved careful introduction and management of risk into the workplace, to encourage innovation through experimentation. This transition has not been easy for tradition-bound organizations.

From the above features, it would seem safe to say that most companies embarking upon the knowledge and learning journey are in the middle of the second stage. Probably, the leaders of the knowledge learning pack are gradually edging to the cusp of Stage 2 or taking their first steps onto the platform of Stage 3.

Managing knowledge and learning has provided the ability to respond to many of the challenges of turbulences in the global economy. Companies seeking to survive and flourish in this new environment cannot afford to ignore the imperative of managing knowledge and learning. Organizational learning and knowledge management are not the next business fads but are part of the next rung on the ladder in the evolution of business organization. In the scenario of future developments, the next step for most knowledge and learning led organizations is to deeply inculcate and embed the values of learning so much that they become ingrained behaviours. This will be the challenge of transition to a values-based organization. In the long run one hopes that knowledge and learning organizations use their reflexes and insights to construct organizational interaction and outcomes harmonious to the natural ecology of the world in which we live. Corporations can be the agents to a better world, but only if they will it.

Conclusion: final reflections

Knowledge and learning systems are not static, and what is innovative today ultimately becomes the starting point of tomorrow. Thus, defending and growing a competitive position requires continual learning and knowledge acquisition. The ability of an organization to learn, accumulate knowledge from its experiences and reapply that knowledge is a fundamental building block of competitive advantage. In this way, knowledge and learning systems create knowledge that enables the company to lead its industry and competitors, and to significantly differentiate itself from its competitors. Such knowledge often enables a company to change the rules of the competitive game itself.

It is sad to note that apart from some notable successes, for the most part companies remain dismal at learning and change. The reason for such a state of affairs is not a lack of individual effort, but the inertia of past organizational actions – the stifling effects of bureaucracy and the inflexibility of collective mindsets that populate most companies. The vast majority of knowledge and learning often succumbs because not all the initiatives have merit but also because many companies lack the ability and stamina to make even good ideas work.

Building knowledge and learning into concrete businesses is extremely difficult because the entire process from concept to a working knowledge and learning system is riddled with unknowns and unknowables. Some of the many uncertainties include whether or not the original knowledge approach and its elements are technically workable, whether the right people can be hired and retained, whether the proposed programme can be undertaken without financially and emotionally draining the firm, whether the firm and its people are ready for it and whether it can be implemented economically. These uncertainties are difficult to resolve because they are often unique to the circumstances of a particular company and there are no off-the-shelf remedies that can be applied generally to problems that arise during the course of unfolding events.

Turning knowledge and learning into real organizational outcomes represents the key challenge for managing it. Knowledge and learning in themselves are worth very little. Only in applying them is their value realized. ‘There is no one best way to design a satellite (no matter how many times people search for one). There are only an infinite number of wrong answers you are trying to avoid’ (quote by a design engineer) and as Thomas Edison once noted, ‘Nothing that's any good works by itself, you have got to make the damn thing work.’