13

Hewlett-Packard

Getting knowledge management started

Hewlett-Packard (HP) began embracing rudimentary concepts of knowledge management around early to mid-1990s. The computer manufacturing giant, with over 100 000 employees and more than 400 locations around the world, started its knowledge management journey from a wellspring of informal interest among independent business units.

By mid-1995 senior staff noticed that several knowledge management initiatives were under way in various parts of the company. Some had been in place for several years; others were just beginning. Acting upon this phenomenon, the leaders of HP's corporate information systems group decided to attempt to facilitate knowledge management practice by setting up a series of workshops. Their idea was to bring together a diverse group of people within the company who were already involved in knowledge management efforts or who were interested in getting started. The main aim of the workshops was to facilitate knowledge sharing through the systematic establishment of informal networks as well as the development of a common language and management frameworks for knowledge sharing.

Hewlett-Packard's organization and culture act as both a facilitator and a barrier to knowledge sharing. The company has a relaxed, open culture that facilitates knowledge exchange. All employees, including the CEO, work in open cubicles. Many employees are technically-oriented engineers who enjoy learning and sharing their knowledge.

Hewlett-Packard is renowned, through the imprint of its founding fathers, for its benevolent attitude towards employees. This was abetted by a munificent environment and fast growth that allowed the company to avoid major layoffs. The nature of the organization employee relationship is such that all HP employees participate in a profit-sharing programme and it is common for employees to move from one business unit to another. Combined, these factors have helped to create a bond between employees and the organization, which, coupled with mobility, facilitates possibilities for informal knowledge transfer within the company.

Working against this, however, is the company's highly decentralized organizational structure and mode of operations. The push to change this structural set-up has been resisted because many within HP firmly believe that the strong business-specific focus brought by decentralization is a key factor in the firm's success. Business units that perform well enjoy a very high degree of autonomy. On the negative side, this has meant that there is little organized sharing of information, resources or employees across units. Thus, despite a cultural openness towards sharing, few business units were willing to invest time or money in efforts that do not have an obvious and immediate payback for them. Nevertheless, appreciation of the weaknesses of a highly decentralized structure heightened sensitivity towards knowledge management. Moreover, at the grass-roots level there has long been a desire among employees to ‘know what HP knows’.

The first workshop, held in October 1995, discovered that there were some twenty separate knowledge management programmes under way in various parts of the corporation. Knowledge management programmes were being independently pursued within a diverse set of groups, that ranged from HP Corporate Education to HP Labs, from HP Product Processes Organization (responsible for the corporate mission of advancing product development and introduction) to Corporate Consulting. From these we examine the Corporate Consulting effort since it set the basic template for others.

HP Consulting: laying the paving for knowledge management

HP Consulting is a 5000-strong global consulting organization. HP Consulting offers its clients a variety of services, including IT service management, enterprise desktop management, customer relationship management and enterprise resource planning services. HP Consulting's business success is inextricably linked to its ability to provide high-quality business advice to clients and in this way deliver increased profits to HP's bottom line. Its ability to share and leverage knowledge underpinned the unit's business performance. Despite this, sharing of knowledge at HP Consulting remained informal and serendipitous, based on personal networks and chance meetings. HP Consulting began to recognize that its success was heavily dependent on the ability to manage and leverage organizational knowledge both efficiently and effectively. Lew Platt, Chairman, President and CEO of HP captured the case well in stating: ‘Successful companies of the twenty-first century will be those who do the best jobs of capturing, storing and leveraging what their employees know.’

Another motive for becoming a knowledge-based organization was the distributed nature of the global consulting teams and increasing client expectations that HP's collective experience should be used to solve their technology problems. Moreover, many competitors were implementing knowledge management programmes with the same goals in mind.

HP Consulting had come to believe that sharing, leverage and reuse of knowledge had to become part of its culture. This, however, was not the first attempt at managing knowledge within the company. Previous attempts to share and leverage knowledge at HP Consulting had focused on groupware technology and information repositories. Unfortunately, these attempts failed. These failures were thought to have occurred as a consequence of neglecting the human side of knowledge management. In particular, the early initiatives had failed to recognize the importance of the roles played by leadership, processes and culture. Technology had been poorly integrated with work processes, and information stored within the databases had not been structured in a way that made it easy to access.

The knowledge management initiative

In 1996 a fresh knowledge management initiative was launched with three key objectives:

1 To deliver additional value to customers without increasing the hours worked.

2 To bring more intellectual capital to solutions.

3 To create an environment in which people were keen to share knowledge with others.

To achieve this aim the company knew that they had to have a clear intention and adopt a process approach. Additionally, the change effort would need a high level of senior management sponsorship and commitment.

In sum the task, in the words of HP Consulting's General Manager, Jim Sherriff, was ‘to make the knowledge of the few the knowledge of the many’. The company needed to tap into the knowledge of the more experienced consultants. All consultants in the organization needed to feel and act as if they had the knowledge of the entire organization, at their fingertips, when consulting with customers.

Assessing organizational readiness

An assessment of the organization's readiness for change was conducted through interviews with HP Consulting's managers, consultants and clients. The assessment allowed the company to gauge the current level of knowledge sharing, leverage and reuse, and to discover inhibitors to these behaviours. This proved to be useful in uncovering the likely problems and challenges that lay ahead. From this assessment the following issues emerged:

1 Without visible leadership commitment the programme would most probably fail.

2 There was a lot of ‘reinventing of the wheel’. There were few examples of successful knowledge sharing or reuse. In HP's words ‘we invent the wheel, not just daily, but hourly’.

3 There was a lack of practical processes and tools to share, leverage or even to find out who in the organization had the needed knowledge.

4 There was a perception that knowledge sharing would be further burden to an already full work schedule.

Following the organizational readiness assessment, an action plan was developed and mandated by the leadership.

The approach

Due to the earlier failures, HP Consulting launched the new knowledge management initiative using pilot programmes that focused on behavioural elements. The key features of this were to:

- allow time to reflect and learn from successes and mistakes

- develop an environment that encouraged sharing of knowledge and experiences

- encourage the development and sharing of best practices, tools and solutions that could be leveraged by other consultants.

Two consulting practices located in North America were selected for participation in the pilot programme. The selection of the two practices was driven by the belief that these two were facing challenges which would benefit most through a sharing and leveraging of knowledge. Both practices were in the process of implementing new services, and had only a handful of consultants with previous experience of delivering such services. The challenge was to quickly ‘ramp up’ consultants around the world to effectively sell and deliver the new solutions.

The pilots were also an experiment to learn quickly what worked and what did not, and to make improvements for widespread knowledge management efforts.

Launching the knowledge management initiative

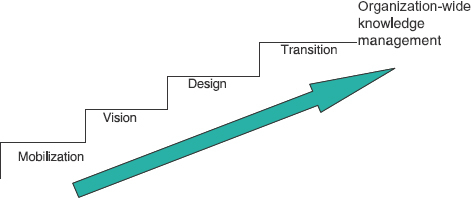

The approach used to launch the knowledge management initiative utilized a four-step change model: mobilization, vision, design and transition (Figure 13.1).

Fig. 13.1 Four steps to organization-wide knowledge management

Step 1: mobilization

The mobilization stage was considered an important precursor for enacting change. It was to familiarize the pilot teams with the business imperative and objectives for knowledge management.

Step 2: vision

Developing a vision statement served to energize the leadership, pilot teams and, eventually, the whole organization. The vision statement, which was formulated and continues to endure is:

Our vision is that our consultants feel and act as if they have the entire organization at their fingertips when they consult with customers. They know exactly where to go to find information. They are eager to share knowledge as well as leverage other's experience in order to deliver more value to customers. We will recognize those consultants that share and those that leverage others’ knowledge as the most valuable members of the consulting team. To achieve this, we need everyone to take personal responsibility for sharing knowledge and learning from each other.

The vision statement became a guidepost for the knowledge management initiative and was the rallying cry for the pilot programme participants.

The leadership also identified and promulgated four values for sustaining the knowledge management effort. The values were:

1 Leveraging other people's knowledge, experience and deliverables is a desired behaviour.

2 Innovation is highly valued when both successes and failures are shared.

3 Time spent increasing both one's own and others’ knowledge and confidence is a highly valued activity.

4 Consultants who actively share their knowledge and draw on the knowledge of others will dramatically increase their worth.

Step 3: design

The purpose of this stage was to design processes for sharing experiences and surfacing knowledge for reuse.

The initial pilots focused on coming out with generic processes and mechanisms to enable knowledge management. These processes would need to provide for the connection and interaction among participants, i.e. they had to be designed so that they could tap the knowledge locked in people's heads and capture the knowledge that needed to be leveraged from a few consultants to many consultants. Three basic formats were formulated, each with a slightly different purpose and positioning:

1 Learning communities. These would comprise informal groups of people. Membership would cross organizational boundaries. Members would come together to discuss best practices, issues or skills that the group wanted to learn about. They would be able meet face to face or through conference calls.

2 Project snapshots. These were to be sessions designed to collect lessons learned and compile collateral from a project team that potentially could be reused by a future project team.

3 Knowledge mapping. This would be a process which would help identify the knowledge, skills, collateral and tools needed to sell or deliver a solution. Consultants with experience would need to come together to build the map based on their experience and know-how. The map would be used as a guide to what knowledge is important and where it can be found. It is updated as experience in the organization grows.

Step 4: transition

In order to make sustained change in knowledge management, the design team needed a way of introducing the new knowledge processes, values and behaviours.

To define the best way to do this a two-day workshop was designed and tested with a subset of the pilot programme participants. This workshop allowed the design team to evaluate the results of their efforts and decide whether modifications to the design were needed.

This stage also provided ammunition to tout the successes of the pilot teams. This was useful to build confidence and help prepare the organization for the long journey to permanent change that lay ahead.

The workshop: a look into the experience

Two project teams were selected to participate in the first workshop. The workshop's aim was to stimulate immediate behavioural change, so that the value of knowledge sharing and reuse became evident quickly. The workshops were also a way of providing a safe environment to practice the initial reflexes and behaviours necessary for knowledge sharing. The experience of the workshop is captured in the discussion that follows.

Initially, participants struggled with the relevance of knowledge management to their work. One of the leaders surmised, ‘The first day was a disaster. The group wanted nothing to do with the “fluffy stuff”. They wanted technical training’.

The breakthrough came when the facilitators stopped the presentation format. At this point the participants were arranged in circular seating and a dialogue was opened.

It soon became apparent that the major source of resistance stemmed from the consultants’ perception that they already had the values and behaviours that were being suggested, and therefore saw the whole workshop exercise as ‘a waste of time’. Eventually, the deadlock began to break after the senior practice leader interjected to make a clear cut case for why knowledge management was absolutely vital for the future of the business and the urgency of taking action:

While you may not believe knowledge sharing and reuse is important to the success of our business, our clients say different . The client feedback collected during the assessment phase reflects that our clients believe that the depth of our knowledge is dependent on the consultants assigned to their project. Our challenge is to be able to deliver these new services in a consistent, high-quality manner. To do this, we must rapidly leverage our experience so we can learn what works and what doesn't, and grow our capability to deliver globally. We have a small window of opportunity and knowledge management is key to our success.

Thereafter, slowly but gradually, an understanding of the importance of knowledge sharing and leverage to them, to their clients and to the business began to permeate the group. This was reinforced when a consultant, who was well respected for his depth of technical capability, spoke out: ‘I've been working with the design team for several weeks. At the beginning, I was sceptical about the value of knowledge management too. However, I now see how important it is to our success.’

The combination of customer feedback, leadership support and the buy-in of a respected team member created the breakthrough that the workshop needed. After this point, workshop participants moved from resistance to what they wanted to get out of the workshop experience.

The pilot participants began to ask questions and surface old assumptions and models of practice. It was not long before the pilot participants arrived at the realization that knowledge is based on experience and exists in the minds of individuals. They also began to notice the different shades of knowledge and the different management challenges facing them. As one consultant commented: ‘Paying attention only to knowledge captured in a database is like a wine connoisseur paying more attention to the bottle than to the wine. Paying attention only to the human capital would be like a wine maker not paying attention to bottling or distribution.’

The success of the workshop can be easily ascertained from the participants’ sentiments:

The workshop had specific personal impact to me. It convinced me to work on changing my behaviour, and helped me to see the value of sharing knowledge and learning from others. It clearly demonstrated that technical ability alone is not sufficient for success.

We'll talk about the things we did wrong; we hope others will be just as honest with us. We're going to learn a lot from each other.

Overall, the consultants agreed that the workshop encouraged them to rethink their relationships with each other and with customers.

Launching Learning Communities

Given they had already experienced frustration with past attempts at leveraging knowledge through repositories, the pilot teams chose to start by launching Learning Communities. The logic behind this was that Learning Communities would provide a process and environment for the consultants to connect with each other, learn from each other and experience the value of sharing and reuse. The plan was to incorporate over time the other knowledge processes, namely project snapshots and knowledge mapping.

After the workshop, the first group of participants began to form Learning Communities. Initially four Learning Communities were launched. The four quickly grew to seven. The Learning Communities were designed to ensure that their activities would create value by structuring discussion around key consulting issues, the development of core competencies or the sharing of best practices.

The Learning Communities also involved consultants who had not participated in the workshop, but were within the scope of the pilot. The design team established a process for capturing feedback from Learning Communities in the form of anecdotal stories. Stories played a major role in motivating and sustaining enthusiasm. The telling of stories helped to reinforce the value of establishing processes for sharing and leveraging knowledge.

Tangible and intangible benefits were soon being reported as a result of Learning Community sessions. Even early on in the process HP Consulting began to note gains such as:

- a reduction in delivery time while improving quality through leveraging best practices

- reusing and standardizing proposal and presentation materials resulting in increased productivity

- sharing a broad range of tacit knowledge resulting in improved know-how of the community members.

Enthusiasm for knowledge sharing and reuse grew with those participating in the pilot. One Learning Community participant provided the overall sentiment: ‘The Learning Community is creating a connectedness among us. We all feel we can go to each other for help. That's a big benefit for people who spend a lot of time at customer sites.’

Moving from pilot to company-wide initiative

For HP Consulting, the pilots were the beginning of an organization-wide initiative to make the knowledge of the few the knowledge of the many. The design team rapidly moved from the pilot to implementing the knowledge processes routinely in the HP Consulting global organization. The key lessons arising from the experience were:

1 Leadership must provide a foundation for change through unequivocal support and motivation.

2 Sponsors must be both evangelists and role models.

3 Knowledge management is not a programme but a new way of working that needs to be embedded into the overall strategy and organization design.

4 Focus should be on the critical business knowledge; not all knowledge is equally valuable.

5 Knowledge management begins with processes to share and create knowledge and is sustained by a knowledge-friendly culture.

6 People are willing to share and reuse knowledge if they feel it is desirable and expected behaviour.

7 Technology is an enabler, not the driver.

Challenges in the future

By 1998, sharing knowledge and structuring intellectual capital for reuse had become part of HP Consulting's strategy. One of two strategic objectives was for consultants in the organization to become knowledge masters. Knowledge management progressed from an initiative to becoming an intellectual capital work group whose purpose was to lead the transformation of HP Consulting to a knowledge-based business.

Hewlett-Packard made a concerted effort to knit the knowledge processes into the way work gets done. As the processes became embedded within everyday work, enabling technology was carefully added. As more and more technology has been added, new challenges such as content management and the structuring of the explicit intellectual capital have become priorities. The company also began to devise and implant performance metrics in consultants’ roles to further reinforce that knowledge sharing, leverage and reuse is part of everyone's job.

Hewlett-Packard's approach has been one of emphasizing awareness and through this developing of a common vocabulary and knowledge frameworks. The workshops approach has been a subtle one. This was deemed to be the most appropriate for HP's culture at the time.