24

Xerox

Over many years Xerox has experienced change from a great number of directions and at a faster pace than have most companies. In the 1980s it survived a crisis that took it to the verge of bankruptcy, and managed to turn itself around by leading the introduction of quality management ideas in the West. It achieved wide recognition for doing so when it won the coveted Baldrige Award in the USA in 1989 and the European Quality Award in 1992. But few people know that this philosophy has been complemented and even superseded in the 1990s by a highly focused approach to empowering and developing people that is being credited inside Xerox with keeping the company at the forefront of innovation and growth in its markets.

Competing in a turbulent environment

Xerox Corporation dominated the early days of copiers. The machines first appeared on the US market in 1950, but did not become widespread until after the first automated office copier was launched in 1960. The company set up a joint venture with the Rank Organization in the UK to provide copiers outside the USA, which then developed markets throughout Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, and in turn set up a joint venture with Fuji in Japan in 1962.

When the original patents on copiers started to run out in the mid-1970s, Xerox was preoccupied by fears that leading European and US companies such as IBM or Kodak, might enter its market. Unfortunately, in common with many other Western businesses, it failed to anticipate the threat from Japan. Jolted by Canon, Xerox's market share fell to an all time low of 7 per cent in the 1980s.

Xerox recovered from its setbacks in the 1980s by prioritizing quality and concentrating on large customers that were prepared to pay a premium for more versatile and reliable copiers. In 1991 it introduced a ‘total satisfaction guarantee’, pledging to change or replace equipment less than three years old, at no extra cost and with no questions asked. Xerox has clawed its way back to a market share of 17 per cent of new machines installed. It dominates the top end of the market, where customers are prepared to pay higher prices for increasingly sophisticated machines.

The experience of the 1980s has made Xerox acutely sensitive to new threats. It found that while it may be ‘the world's leading document processing company’ it faces competition from multiple directions, most notably in software, printing and telecommunications. Moreover, it is a more narrowly focused business than either of its main rivals, Canon and Hewlett-Packard. Xerox's policy worldwide is to secure access to related technologies through partnerships with telecommunications and IT firms, including AT&T, IBM and Microsoft.

In line with environmental shifts the 1990s was an era of shifts in focus. Xerox moved from light lens to digital technology, from stand-alone machines to connected ones, culminating in an overall move from product to solution provider. This reflects Xerox's aspiration to design and provide a complete service for customers. Worldwide, Xerox spends more than $1.5 billion a year on research and development, out of a turnover of $18 billion.

These changes eventually led to the promulgation of a new vision, values and goals between now and 2005, dubbed Xerox 2005. The overall aim of Xerox 2005 is to target a doubling of the number of customers. Xerox 2005 guidelines note that Xerox's productivity flows from knowing where the customers need to be next and what solutions they will need to get there.

Knowledge management strategy

Xerox has been consciously managing knowledge since 1990, when it repositioned itself as a ‘document company’ as part of a new fifteen-year strategic outlook and adopted its Year 2005 plan. Today, it is recognized as one of the top five ‘Most Admired Knowledge Enterprises’ chosen by senior executives at Fortune's Global 500 companies. Xerox's reputation as a leading knowledge company has been built on a strong knowledge-sharing culture. This culture has become a catalyst for the company's development of knowledge-intensive tools and technologies for efficient knowledge sharing, developed from its existing base of copier, printing and scanning technologies.

Consistent with that strategic alignment is the active encouragement and support that senior management gives to each business unit's knowledge management effort. The leadership believes that the company can gain a significant competitive advantage by leveraging the knowledge contained in the heads of 90 000 employees, its archives of patents and processes, and countless documents stored around the world in various digital formats. Xerox has used its knowledge management initiative to drive forward its business strategy of evolving into a total digital network solutions company.

The knowledge management initiative, from its very beginning, was supported from the very top. Paul Allaire, CEO of Xerox, officially started the knowledge management initiative in 1996, a year in which Xerox also began its major long-range planning effort, Xerox 2005. This planning process was to help the company envision where it was going into the future: where technology was going, where customers were going and what geographies were changing. Xerox asked a series of questions about the knowledge management movement: was it a genuine movement? Should Xerox jump on the bandwagon? If so when and how? What level of resources should be devoted to it? To answer these questions Xerox, led by Dan Holtshouse, Director of Strategy and Knowledge, initiated a study of forty companies and their efforts at knowledge management. The conclusion emerging from these case study examinations was that many companies were deriving significant benefits. The study also allowed Xerox to define ten domains or categories of knowledge management:

1 Sharing knowledge and best practices.

2 Instilling responsibility for knowledge sharing.

3 Capturing and reusing past experiences.

4 Embedding knowledge in products, services and processes.

5 Producing knowledge as a product.

6 Driving knowledge generation for innovation.

7 Mapping network experts.

8 Building and mining customer knowledge bases.

9 Understanding and measuring the value of knowledge.

10 Leveraging intellectual assets.

These categories encompass the many varieties of knowledge management programmes that companies were undertaking. Most companies stressed one or few of these categories within their programmes. Xerox's initial focus began with knowledge sharing, which was deemed to be fundamental for success in the other domains. Xerox (on the basis of a study by Delphi Consulting Group) believed that only around 12 per cent of the organizational knowledge in any company is in some sort of knowledge base where it can be easily accessed by others who need it. The largest amount (46 per cent) exists in paper and electronic form, which theoretically should be available for sharing but is not because of paper to digital difficulties, incompatible databases, etc. Documents were the major vehicle that people use to share knowledge with each other, but the divide between paper and digital documents was a serious hindrance to knowledge sharing. Going beyond these findings, Xerox's own research highlighted that an even more significant barrier to knowledge sharing in the workplace was the natural human resistance within traditional workplace environments, especially those in which knowledge was equated with power and where hoarding was a dominant paradigm. Xerox deduced from this that improving knowledge sharing in a meaningful way required a delicate marriage of technology to cultural and sociological dimensions of the organization.

From its external studies Xerox knew that many knowledge management initiatives result in failure. Xerox avoided this by attempting to focus on the right thing from the start. Rather than emphasizing the IT infrastructure of knowledge sharing and forcing employees to either adapt or fail, Xerox went to great lengths to tailor its knowledge management initiatives to its people, by understanding how they do their jobs and the social dynamics behind knowledge sharing. Indeed, the major thrust of Xerox's knowledge management strategy is toward an overall cultural focus for knowledge sharing. Xerox's knowledge management programmes are the enablers that allow its employees to share their knowledge. Chairman Paul Allaire says that aligning knowledge management and its related technologies with the way people function in the workplace is key: ‘Fundamentally, the way we work is changing, and we have to look at ways to help shape the workplace of the future through technology … Because work has become much more cooperative in nature, technology must support this distributed sharing of knowledge’.

Knowledge sharing at Xerox

A key aim at sharing of knowledge at Xerox is to accelerate learning and innovation. This is considered to lie at the heart of competitive advantage. Indeed, such considerations led Xerox away from the analogue copier business to digital copiers in the mid-1990s and to digital document networking today. Xerox firmly believes competitive advantage is drawn from learning faster than the competition, and in companies where power is acquired by hoarding knowledge, learning cannot take place effectively. Knowledge sharing is not just about telling hoarders to co-operate. It is about capturing the tacit knowledge locked in people's heads. For Xerox, the challenge was to capture and transform such knowledge into a sharable form. This is quite a tall order when tens of thousands of people are involved in the sharing. This challenge was the seed leading to the evolution of project Eureka.

Eureka

Eureka started out as a grass-roots effort to share intellectual capital, driven by business necessity. In project Eureka, Xerox created a system with which service engineers could share tips for fixing copiers. This project grew out of two problems with service manuals: they were out of date almost as soon as they were printed, and they failed to incorporate many of the innovations that repair technicians improvized while in the field. Technicians could make up to a million service calls a month to maintain, printers, copiers and other aspects of customer operations. During these calls they constantly were discovering new solutions to repairing unique problems. Repair successes stories were commonly shared in work group meetings in the form of stories, but circulation occurred among only a few. These factors created situations where an engineer often found himself or herself with no solution in the manual and no one around to help. These environmental and social factors were drivers to project Eureka. Xerox social scientists and computer scientists teamed with the service engineers to create systems in which tips were contributed by the technicians, validated by respected groups of peers and then quickly made available to the community through digital technology.

How the Eureka tips system works

The Eureka tips systems is based on four basic steps: authoring, validating, sharing and using tips.

1 Authoring tips. Xerox developed ‘authoring tips’ by examining the different possible ways people use to express themselves. While keeping the process simple for the end user, Xerox made authoring flexible and creative. Along with written suggestions, an author can attach diagrams, sound or other supporting material. His or her name gets listed on the tip form, providing credit but also ensuring seriousness of the entry. The entry is uploaded when the technician has time to connect to the Internet, and then it is put into a pending knowledge base for review.

2 Validating tips. Tips are reviewed by respected and trusted experts. Validators review the tips by downloading them from the server to their laptops. The author is automatically notified and the validator's name is added to the tip. The resulting conclusion of the check is then uploaded on to the server. Validated tips are then made accessible to the community.

3 Sharing tips. The practice of telling stories, improvements procedures and checklists within the community is enhanced through the validation process and technological dissemination. The technology enables users to download new solutions from the knowledge base to their laptop with notification. This downloading process enables the user to have portable knowledge base that can be used without a network connection.

4 Using tips. Problems are constantly encountered in the field, and there is a pressure to solve them quickly and efficiently. Solutions have to be accessible and immediately practical. Searchlite, Xerox's proprietary search engine, helps fulfil this need. Using Searchlite, users can conduct searches and also customise search procedure to suit their needs and contexts. Searchlite contains filtering options, fuzziness and other options that help engineers’ find the right solution. Contact information of the author and validator are listed within the feedback too. This feedback allows the engineer to record outcomes, which subsequently can be aggregated to develop a success rating.

Eureka was originally field tested in France with 1300 service engineers. Xerox France reported a reduction of 5–10 per cent in costs and parts usage. The project moved Xerox France from being one of the worst performers among Xerox service organizations to being best in class. Five to ten per cent savings projected on to the 25 000 labour force translates into serious money. Success in France led to the global roll-out of Eureka. It now has more than 14 000 users across France, Canada, the USA, the UK, The Netherlands, Germany, Brazil, Argentina, Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Mexico. Users can submit tips in their native language and, if validated, they go into the system in English. The Eureka knowledge base currently boasts in excess of 34 000 solutions, and the knowledge base continues to grow at around 400 tips per month. The system is also being expanded to include field analysts and customer support centres.

Eureka is self-sustaining, since it encourages efficiency, cost savings and high involvement in the service part of the organization. The success of the voluntary submission of shared tips is primarily because service engineers get personal recognition for their contributions; their name goes with the tip throughout the life of the system. Beyond developing intellectual capital Eureka has facilitated the development of social capital by allowing employees to get to know other employees outside their immediate work circles. Now service engineers have become part of a global community. For instance, a solution developed in Toronto was used in South America. The user e-mailed the author to tell him that his tip was terrific: ‘You saved me replacing a $40 000 machine by simply replacing this 90-cent connector. I would never have figured that out.’

For employees who are scattered around the world and travel often, the ability to share such know-how has meant that they do not have to miss out on the kind of knowledge that is typically exchanged around the coffee machine. Eureka's knowledge sharing technology has had a significant impact on the culture of the entire workforce. Commenting on the project, Holtshouse stated ‘We're starting this knowledge-sharing initiative as a cultural dimension inside of Xerox … Knowledge sharing is going to become part of a fabric inside the company, for all employees.’

Making knowledge management work

Many companies have attempted to install knowledge management systems and have invested heavily in IT systems such as expert databases and intranet sites, only then to foist them on a workforce. Employees often resist such introductions leading to inevitable failures.

Recognizing failures, Xerox identified two clear problems that it needed to keep in mind while developing its knowledge management infrastructure:

1 Technology itself can be off-putting. Employees often have a difficult time in using computer systems, and some are even embarrassed to call the systems administrators for help, preferring simply to give up.

2 People loathe spending time adding content to a knowledge repository and, in the final analysis, a database is only as good as the information it contains.

Xerox, despite the technological focus of its business, managed to sidestep these problems through adopting a socio-cultural emphasis. Laura Tucker, manager of the company's technical information centre, highlights that ‘Knowledge management at Xerox is not technology-driven. It's people-driven’. Internal Xerox experts estimate that 80 per cent of designing knowledge management systems involves adapting to the social dynamics of the workplace. Only 20 per cent involves technology as an enabling mechanism.

With Eureka, for instance, the goal was to develop a system that would suit field technicians and provide tools which allowed them easily to populate the database with content. Hence the link to laptops, which are standard issue at Xerox. The company also discovered that the technicians were more than happy to add tips to the database because they received credit for their contributions, which enhanced their standing among colleagues. When management suggested attaching financial incentives to the tips, technicians resisted the idea. They felt this would diminish the value of their contributions.

DocuShare

In another effort to create and share intellectual and social capital, Xerox focused on connecting its research community. The research community had a desire to share but were hampered by organizational, technological and geographic barriers. The resulting tool, first called AmberWeb and later DocuShare, allowed scientists to collaborate among themselves. DocuShare is an Internet-based document repository and virtual workspace. The research scientists wanted minimum structure and also wanted to self-maintain and self-organize their workspaces. By utilizing skills in social and anthropological sciences, Xerox designed DocuShare as an easy to use, easy to maintain and organize format. It has no central authority or management.

DocuShare has migrated outside the science arena to engineers and product designers. From a handful of scientists, the tool is now embraced by more than 30 000 employees from all corners of the company. DocuShare is available company-wide and allows work teams to create a ‘virtual’ office space on the corporate intranet: a three-dimensional room where visitors can navigate through and access filing cabinets containing electronic documents. Individual users set codes to determine who can have access to their documents and who cannot. All members of a group can visit any filing cabinet in their ‘room’ and give access codes to employees from other work groups. The tool encourages typically secretive and insular scientists to share information with colleagues, while respecting their need for privacy. Docushare has helped break down the barriers of distance and the product silos that previously pervaded the company. In facilitating information reuse, DocuShare reduces development costs and potentially stimulates new applications for the same knowledge. All of these ultimately increase the information's absolute value.

DocuShare also takes into account what motivates people to share knowledge. During the early design phase, Xerox hired anthropologists to help understand how scientists at the laboratories generally worked, both individually and within groups. It then decided that certain conditions were required for these scientists to use a common knowledge-exchange platform – no training needed to use it, no maintenance and no bureaucracy. It also discovered how scientists set criteria about which information to protect and which to make accessible. These social dynamics affected the technological specifications for the tool.

The DocuShare experience highlights that if the community is involved in the building of the tool and given control over its management, success comes naturally.

Yellow pages

Xerox also avoided the pitfall of poorly designed electronic yellow pages. Those arranged by name and title, for example, do not necessarily help users identify sources of information. In the yellow pages at Xerox, employees identify themselves by areas of expertise. Each employee also has to enter the degree of his or her expertise, broad knowledge, specific knowledge, hobby, etc. so that those seeking help in a given area or subject matter can identify sources. People must register themselves to use the database, thus ensuring that they are available to others as they use the resources.

Portals

Portals, another knowledge management tool used at Xerox, was developed at the company's Palo Alto Research Centre (PARC) facility in California. Portals is a digitally networked tool that uses the scanning technology in copiers to build electronic links between copiers and corporate databases. Instead of just making copies, employees can use Portals to scan in hard copies of documents and transfer them to a hard disk. They can also retrieve documents from anywhere on the corporate database and print them out from Portals. This allows them to capture, search for and retrieve knowledge more efficiently.

According to Mark Hill, Vice President and general manager of the Document Portals business unit, Portals, like DocuShare, was developed from an understanding of people's work habits. Rather than inventing a new digital-scanning device, they decided to combine existing copier technology with people's preference for simple operations. In Hill's words, people are ‘used to hitting the little green button to make copies. By paying attention to the details of the workplace (that little green button), Xerox developed a tool that enhances the number of ways that documents, and knowledge, can be shared’.

Leadership and the human resource challenge

It almost goes without saying that success requires strong leadership support. The knowledge management initiative is no exception to this rule. Xerox senior management's consistent communications, signals and public comments from the top executives ensured that the knowledge management programme remained important and strategically relevant over time.

Besides giving verbal support, senior managers adopt a hands-off policy towards knowledge management projects to ensure that the process of innovation is not hindered by bureaucracy. This does not mean that knowledge management project teams are a freewheeling but, rather than setting specific knowledge management goals in stone, senior management set more traditional organizational goals, such as quality and time to market, leaving associates to develop knowledge management projects that will support those goals.

Indeed, top executives were not looking for quick wins, and their past experience suggested that the biggest strides come from a grass-roots, project-by-project approach rather than grandiose, management-driven initiatives. As Holtshouse notes, ‘In my experience, Xerox has a little more respect for the unknown, of not knowing what the grand picture is to begin with’.

The broader human resource challenge

Paul Allaire, Chief Executive of Xerox Corporation, set the aim is to have a turnover of $10 billion by 2005. Patrick Ponchon (Finance Director, of the former Rank Xerox) states: ‘You don't argue about the targets … only about what needs to be done to deliver the required results – for example, in marketing strategy or product delivery, pricing, coverage of territories and so on.’ So most debate in the planning process is about what needs to be in place to enable targets to be met. Ralph Orrico observes:

Once you've set the vision, the concrete objectives, the priorities and so on, you can't shackle the organization with rigid processes that prevent people from pushing out the boundaries as far as possible … We ask two questions about every work group. First: can they do it? This is largely a matter of people's skills and experience. Then we ask ‘do we let them do it?’, which is more a question of the culture and behaviour in the organization.

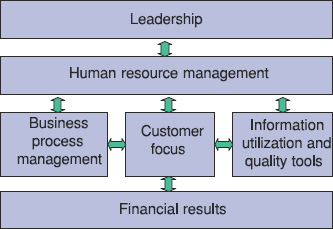

Used in conjunction with the Xerox management model (see Figure 24.1) are two checklists of the skills and behaviours that the company aims to develop and encourage (see Table 24.1). These comprise twenty-three leadership attributes – which some refer to as competencies – and nine cultural dimensions, against which all senior managers, Allaire included, are assessed every year. Xerox believes it target of becoming a $10 billion company can be achieved by developing its managers to embody the ‘23+9’ characteristics.

Table 24.1 Leadership and cultural attributes

The 23 leadership attributes |

The 9 cultural dimensions |

1. Strategic thinking 2. Strategic implementation 3. Customer-driven approach 4. Inspiring a shared vision 5. Decision making 6. Quick study 7. Managing operational performance 8. Staffing for high performance 9. Developing organizational talent 10. Delegation and empowerment 11. Managing teamwork 12. Cross-functional teamwork 13. Leading innovation 14. Drives for business results 15. Use of ‘Leadership through quality’ (the Xerox quality management programme) 16. Openess to change 17. Interpersonal empathy and understanding 18. Personal drive 19. Personal strength and maturity 20. Personal consistency 21. Environmental and industry perspective 22. Business and financial perspective 23. Overall technical knowledge |

1. Market connected 2. Absolute results orientated 3. Action orientated 4. Line driven 5. Team orientated 6. Empowered people 7. Open and honest communication 8. Organization reflection and learning 9. Process re-engineering and simplification |

Each of the ‘23+9’ (as they are usually referred to) is divided into a number of criteria. For example, on the leadership attribute referring to ‘cross-functional teamwork; managers are judged according to whether they:

- understand the roles and responsibilities of functions and divisions, and how they can work across boundaries

- maintain close relationships across organizational boundaries to achieve policy deployment/business results

- recognize diverse stakeholder needs and gain support for shared goals

- negotiate and implement work processes across boundaries.

In the same way, the cultural dimension for ‘open and honest communication’ requires managers to be assessed on whether they:

- are sensitive to the concerns and feelings of others

- do not treat disagreement as disloyalty

- foster feedback, dialogue and information sharing

- encourage openness through personal behaviour

- confront conflict openly.

The 23+9 framework has ensured that line managers are unusually knowledgeable and competent. Not all the 23+9 are equally important to all managers. Jobs at different levels and in different specialisms will prioritize different bundles of leadership attributes. But the framework provides a clear picture of the ideal, rounded Xerox manager, and all employees are asked each year to assess their own managers against it as part of a 360-degree appraisal process. The framework is then used to focus individuals’ development plans and the company's succession plans.

Every year, Xerox's top management team also prioritizes a number of leadership and human resource attributes that it feels need to be strengthened. In 1997, for example, there was a particular push on ‘valuing diversity: The company adopted a target of increasing the proportion of women among its 500 senior managers from 17 to 20 per cent by the year 2000. Individual development is viewed ‘as a shared responsibility’ between the employee, the manager and the company. According to Orrico,

Fig. 24.1 Xerox management model

each employee is expected to take responsibility for their own career, and for ensuring their employability, both within and outside Xerox. But it's up to the manager to ensure that the employee is doing that, and to make development opportunities available. The company has responsibility for making the resources available.

Final words

While knowledge management solutions generally appear to be technical, successful outcomes come about as a result of an understanding of the social dynamics of a particular workforce. Holtshouse sums up Xerox's approach of fitting technology to people instead of the other way round: ‘We started with an intense search around workers, what makes them tick, what's important, what problems they are solving-and then picked technology that suits the solutions. Indeed, a lot of what you know about the social aspects can actually be expressed in the product.’

Eureka and DocuShare are examples of knowledge management solutions that began as modest grass-roots projects. Management funded those ventures without knowing exactly where they would lead. Portals grew out of conversations between Hill, based in Rochester, and Chief Scientist John Seely Brown and others at PARC in California. Xerox's knowledge management practice is successful because of the priority it gives to people. The company examined how social dynamics shape the pattern of knowledge sharing to create technologies that reflect factors such as work habits, the perceived benefits of sharing and the contexts in which sharing is natural. Moreover, the company aligns its knowledge management efforts with its macro-business model, which encapsulates drives for quality and people or, to use the more fashionable word, intellectual development.