Value dimensions and relationship postures in dyadic ‘key relationship programmes’

Abstract

Business-to-business marketing is often concerned with the way in which companies manage strategically important relationships with their counterparts: their key relationship programmes (KRPs). These relationships can be managed through the implementation of specific managerial and organizational structures, commonly implemented via key account programmes (on the supplier side) or key supplier programmes (on the customer side). Underlying this managerial process is an implicit assumption that these important relationships bring some form of additional value to one or both parties involved. However, a dyadic view of how this value is created and shared between the parties remains an under-researched area.

In this conceptual paper, we use the multi-faceted value construct introduced in Pardo et al. (2006) and posit that the buyer's or seller's value strategies can be best understood as being internally, exchange or relationship based. This in turn allows us to analyse the value gained as being the outcome of one of nine generic key relationship postures within any dyadic KRP. We focus on an analysis of so-called ‘managed’ relationship postures and identify a number of dyadic activities and competences that we hypothesize are important in managing such KRPs, and which can form the basis for further empirical research.

Introduction

Strategically important business-to-business exchanges often foster the development of specific managerial and organizational structures that enhance these interactions. They are commonly implemented via key account programmes (on the supplier side) or key supplier programmes (on the customer side). These programmes are hypothesized to provide benefits for both exchange partners and foster long-term, cooperative and collaborative business relationships (Pardo 1999; Shapiro and Moriarty 1982; Sheth and Sharma 1997; Stevenson 1980; Stevenson and Page 1979). Such relationship-induced value management is increasingly being seen as a dominant logic for marketing (Vargo and Lusch 2004).

In order to achieve the managerial and organizational structures that facilitate such key relationship interactions, certain organizational and strategic competences, i.e. specific combinations of resources, are hypothesized to exist (Homburg et al. 2002). However, we argue that these competences cannot be seen as ‘entity-centric’ and simply embedded in the actors, activities and resource composition of one organization, and that key relationship programmes and the mutual value that is created and delivered by them are characterized by ‘dyadic’ strategies that go beyond the frame of single organizational entities, as proposed by Möller (2006). Therefore, we focus on strategically important dyadic relationships as part of companies' management of their specific focal net (Alajoutsijärvi et al. 1999).

Based upon a review of previous work and further conceptual development, we posit that a competence-based perspective of relationship building in strategically important inter-organizational exchanges needs to be analysed, first, from a value perspective in order to understand the different facets of relationship outcomes (Lindgreen and Wynstra 2005; Möller and Törrönen 2003), and second, from the perspective of a dyadic interaction in which the inter-organizational relationship itself becomes the focus of attention (Ford and Håkansson 2006). Research on key account management (KAM) as well as on key supplier management (KSM) and supply chain management has hitherto neglected researching organizational interactions in terms of the value concept or with regard to competence-based management, i.e. a competence-based view of the firm (Day 1994; Reid and Plank 2000; Srivastava et al. 2001).

Before introducing our strategic and competence-based considerations, we will establish in the next section the importance of value in dyadic exchanges as the core concept for an analysis of KRPs.

Value and key relationship programmes

The importance of value for theorizing in marketing is widely recognized (Anderson 1995; Eggert et al. 2006; Georges and Eggert 2003; Holbrook 1994; Ulaga and Eggert 2006; Walter et al. 2001), and it can be posited that value constitutes a pivotal underlying concept in explaining exchange constellations. Collaborative relationships have always been clearly associated with the concept of value, with Anderson (1995) arguing that value is the ‘raison d'être’ of that kind of relationship. However, except for the work by Georges and Eggert (2003), Ulaga and Eggert (2005 and 2006) and Pardo et al. (2006), the very specific context of key account management and key supplier management (collaborative relationships by definition) has not been investigated from the value point of view. In the case of Georges and Eggert (2003), value is observed only from the buyer's perspective. This is problematic in the sense that collaboration implies mutual benefits and sacrifices, i.e. a dyadically grounded perspective (Bonoma and Johnston 1978; Wilson 1978). Ulaga and Eggert (2005 and 2006) and Eggert et al. (2006) report empirical findings on perceived relationship value. However, the focus is not dyadic but organization-centric (in this case focusing on purchasing managers), dealing exclusively with value that is created by suppliers for customers. Developing this further, Pardo et al. (2006) posit a multi-faceted concept of value for KAM and derive key account value strategies (KAVS), focusing on static and dynamic aspects of value strategy. However, the dyadic perspective is not consequently employed, neglecting the interactions between suppliers and customers within a key relationship programme. The only existing dyadic perspective on value creation is provided by Möller (2006) in the context of the strategic competences necessary to sustain general business interactions. Möller's (2006) model, which shares some similarities with Henneberg et al.'s (2005) work, will be discussed below and the distinguishing features of our model will be outlined.

In this way, this paper addresses existing shortcomings in the literature by building on the multi-faceted value construct previously introduced in Pardo et al. (2006) and linking this to different value strategies that are available to supplying and buying organizations utilizing key relationship programmes. This is done based within an axiomatic framework that focuses on the exchange dyad between supplier (key account management) and customer (key supplier management), operationalized as the specific relationship context of a key relationship programme (McDonald 2000; Missirilian and Calvi 2004). In contrast to Möller (2006), we thus posit for our analysis an ‘incremental’ value concept, analysing specifically the ‘extra’ or additional elements that characterize KRP exchanges over and above mere business transactions (Homburg et al. 2002).

Compared with Möller (2006), our proposed model is more specific in two ways and is therefore ‘nested’ within the ‘value-producing system’ approach (Möller et al. 2005). First, we focus on relationships which are embedded within specific organizational structures geared towards expressing the ‘logic’ of this relationship (i.e. KRPs). Second, we analyse concretely the value aspects which can be linked to the decision of committing organizational resources to ‘structure’ this relationship. In this way, the value-production logic as analysed by Möller and Törrönen (2003) represents the general exchange morphology, while our model emphasizes the specific KRP relationship. By including a value logic which can be internally focused, as well as by separating value creation from value appropriation, our model enriches the proposed business-to-business value strategies in Möller (2006). In fact, by allowing for ‘internal’ value focus, we enlarge the ‘value production’ perspective used by Möller and Törrönen (2003) and Möller (2006) by a further element.

In our argument, we thus link the specific elements of value strategies in KRPs, operationalized as a taxonomy of nine different strategic exchange postures, to an understanding of necessary competences to manage these exchange situations and introduce ‘dyadic’ competences as underlying managerial and organizational structures that facilitate optimal value interactions in strategic business-to-business relationships. Our specific focus will be on the so-called ‘managed’ relationship postures. Finally, their viability and economic suitability as well as the underlying facilitating dyadic competences are discussed.

Key relationship value strategies

We posit that a dyadic perspective of value in KRP interactions needs to start with a conceptual understanding of the multi-faceted nature of value (Biggart and Delbridge 2004; Ulaga and Eggert 2005; Wengler et al. 2006), and that value in KRPs can be usefully disaggregated into three levels: internal, exchange and relational value (Pardo et al. 2006). While internal (or proprietary) value is created and appropriated by a single actor in the dyad (Wilson et al. 2002), exchange value is based on the efforts of the supplier and appropriated by the buyer (and vice versa) (Abratt and Kelly 2002; Ulaga 2003; Ulaga and Eggert 2006; Weilbaker and Weeks 1997). Relational value comes into existence because of a collaborative relationship between key account management and key supplier management programmes, i.e. it is created and appropriated within a relationship (Anderson et al. 1994; Pardo et al. 2006).

Such a multi-level value perspective allows us to consider the different value strategies open to players within a KRP, thereby specifying the value production types as introduced by Möller and Törrönen (2003). Both buyer and seller in a KRP need to be aware of all the different value aspects that may characterize their interactions. However, they need to be unambiguous about their specific value focus within the dyadic relationship in order to optimize the activities, processes and resource allocation related to this focus. Furthermore, as part of their value strategies, they also need to take into account the specific focus of the dyadic exchange partner and align their value strategy with that of their counterpart (Möller 2006).

Based upon this approach, we are able to identify three different value strategies available to players within a KRP, these being the strategic postures that we can then use to map the companies' strategy matching activities. It has to be noted that these actor-centric strategies are specific to the rationale of engaging in a KRP, i.e. the strategic relationship with key exchange partners and the associated investments in processes, organization and offering (Homburg et al. 2002):

It needs to be noted that while exchange and relational value strategies are similar to the dimensions introduced in Möller and Törrönen (2003) and used in Möller (2006), our internal value strategy has no equivalent in their categorization. This is mainly due to the fact that our focus is on a specific inter-organizational relationship context, namely KRPs, which are influenced by manifold motivations by actors which can be internally focused or externally oriented (Pardo et al. 2006).

Strategic matching of relationship postures

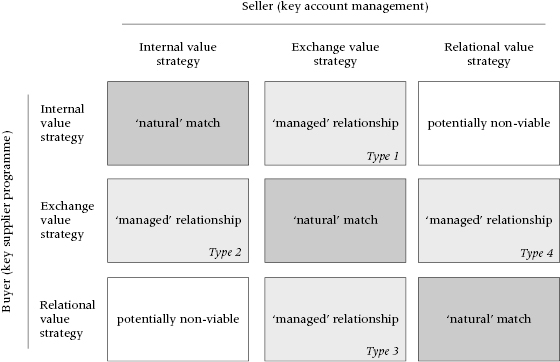

While companies can choose to focus on one of these value strategies as a rationale for their investment in KAM or KSM, or possibly on a portfolio of these strategies (Campbell and Cunningham 1983), the success of such a decision is not independent of the strategic orientation of the dyadic partner. The value strategy chosen by the dyadic exchange partner may be conditional or influential for its own strategic positioning regarding its value focus (Parolini 1999). That means that certain value relationships are not necessarily complementary. In fact, they may be non-viable or need active management and coordination. Based on the three identified value strategies, Figure 1 shows nine generic dyadic key relationship postures, indicating some possible mismatches. This approach is isomorphic with the dyadic interaction approach as suggested by Campbell (1985) and also used by Möller (2006) for an analysis of general value strategies within business-to-business marketing. Therefore, part of the strategic decision-making in KRPs must be a ‘matching’ exercise which can be determined through negotiation (Möller 2006; Mouzas et al. 2007; Pardo 1999).

Figure 1 Nine generic key relationship postures in a KRP

The grid of key relationship postures shows that both parties are able to focus on each of the three key relationship value strategies independently, i.e. they are autonomously able to decide on different internal and external ways of value creation and on the appropriation aims of their value orientation. However, we posit that not all combinations of strategies, i.e. dyadic postures, are viable. A natural match exists when both parties individually focus mainly on the same facet of KRP value. For example, if both seller and buyer organize and manage their respective KRP structures so as to optimize proprietary value (i.e. in our terminology, both sides use internal value strategies), a workable equilibrium between both companies exists: expectations regarding the essence of the KRP are aligned, incremental value is not contested between both sides, and organizational structures and processes do not overlap, i.e. the KRP as such does not need to be ‘managed’. Consider, for example, the relationship between SinalcoCola and the retailer Rewe in Germany. Both manufacturer and retailer organize and manage their respective KRP structures in order to optimize proprietary value as both parties use internal value strategies. Rewe needs SinalcoCola, a relatively small player in the caffeinated beverage market, to leverage its power during the annual negotiations with Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. Meanwhile, SinalcoCola treats Rewe, one of a whole range of possible distribution channels, as a strategically important account in order to achieve the internal operational efficiency which allows the management of such a diversified distribution network. Manufacturer's and retailer's expectations are aligned, incremental value is not contested, and organizational structures and processes do not overlap.

The situation, however, is different when both parties do not use the same value strategy focus. If we envisage the selling company focusing its key account management on an internal value strategy, while the buying company aligns with an exchange value strategy, a dyadic ‘mismatch’ exists: the buyer has expectations regarding value appropriation that are not necessarily reciprocated by the seller. In this example, the seller appropriates value that exists because of its own key account programme. On top of that, it receives value from the customer through its key supplier management programme. Obviously, the buyer expects long-term gains from this exchange (Blois 1999), e.g. in the form of incremental value delivered by the seller and appropriated by the buyer. If both parties implement their part of the dyadic exchange in isolation, this long-term reciprocity (or value equilibrium) would not be achieved. This could mean that such a ‘relationship’ would not be formed in the first place. However, the situation is not necessarily non-viable (i.e. would result ultimately in a breakdown of the strategically important relationship). We characterize it as a ‘managed relationship’.1 This means that besides the dyadic interactions that constitute the underlying exchange, this situation is workable if dyadic negotiations and alignment on the level of value strategies exist (Ritter et al. 2004). This would potentially allow for a system to be developed between both parties, based on a mutual understanding of the specific rationale as to why both are engaging in the dyadic KRP. Therefore, both parties could continue their ‘non-matching’ value strategies within a framework that establishes an equilibrium of mutual value. However, such a ‘managed relationship’ is less stable than a ‘natural match’ and needs to be negotiated and monitored constantly (Mouzas et al. 2007). This means a much higher level of interactivity and information-sharing is necessary between both parties within the KRP, i.e. the ‘networking overheads’ are higher. In order for this to happen, certain ‘dyadic competences’ are necessary, as discussed below.

In our grid, we indicate that two postures are potentially non-viable, so that even strategic matching exercises would not allow a ‘managed relationship’ to be developed. Consequently, it is posited that such postures would be unstable in the medium to longer term and would ultimately cause the disintegration of the dyadic KRP. Such a situation is envisaged when any matching between an internal value strategy and a relational value strategy is attempted. By definition, these strategies are antagonistic towards each other: relational value depends on the co-creation of value while an internal value strategy is based on an intra-organizational orientation towards incremental value. In this constellation, one party is not willing to engage in value creation by the relationship. In its extreme form, where there is an incommensurable dyadic position regarding the mutual expectations of the two parties, no amount of negotiation between the parties short of a value strategy change would make this posture viable.

A competence view of key relationship postures

Implied in the discussion of relationship postures is the argument that the optimal design of a KRP is not primarily an intra-organizational task focusing on the recombination of resources (as, for example, implied in the analysis by Homburg et al. 2002). Such a focus would work only in the cases of the three ‘natural match’ postures shown in Figure 1. In such cases there is a workable equilibrium in the dyadic relationship, even if the relationship value itself is not fully exploited. In addition, we can assume a migration over time of a particular relationship from top-left to bottom-right in Figure 1, as the two parties continue to work ever closer together, thereby reducing uncertainties and increasing cooperation (Anderson and Narus 1991; Ford et al. 2003).

However, many KRPs are likely to lie in the four ‘managed relationship’ postures. In such cases, typified by slightly differing strategic value orientation between the two parties, a successful working relationship depends crucially on strategic matching (Möller 2006), and consequently on the ongoing process of negotiating and re-negotiating the KRP relationship. This cannot be done by one organization alone, and it is therefore a ‘dyadic competence’ that is important, if not necessary, for any matched KRP. This dyadic competence depends on the interaction patterns of both partners: their ability to understand the value strategy focus of their exchange partner; their ability to communicate their own value strategy focus and the shifts in it; their empathy about what is possible within a specific posture defined by the respective value strategies of both partners; their willingness to find a ‘value match’ and to manage this agreed posture constantly via interactions; their ability to measure value not just for themselves but also for their exchange partner; and their (often lack of) willingness to use power to enforce a solution (Mouzas et al. 2007). Such matching strategies have been discussed not just in terms of marketing strategy but also regarding supply chain alignment (Prévot and Spencer 2006). This is in line with a dyadic interpretation of the concept of ‘network competences’ as introduced by Ritter and Gemünden (2003). Such competences in an inter-organizational exchange system have been described as contributing to organizations' ‘network insight’ (Mouzas et al. 2007).

To achieve this competence, it is not enough to build efficient and effective key account management and key supplier management structures independently. This competence, in line with its characteristic of being dyadic, resides crucially in activities and resources that are shared between the two exchange partners (Golfetto and Gibbert 2006; Möller 2006). We can hypothesize that each of the four ‘managed relationships’ shown in Figure 1 would require its own particular set of dyadic value strategies. These are shown in Table 1 and discussed briefly in turn, always with the perspective of moving the relationship from ‘top-left’ to ‘bottom-right’ as noted above, in order to achieve maximal value from the relationship over time.

Table 1: The four different ‘managed relationships’

| Type 1: Seller's exchange orientation, buyer's internal orientation |

| Seller drives managed relationship |

|

| Type 2: Buyer's exchange orientation, seller's internal orientation |

| Buyer drives managed relationship |

|

| Type 3: Seller's exchange orientation, buyer's relational orientation |

| Buyer drives managed relationship |

|

| Type 4: Buyer's exchange orientation, seller's relational orientation |

| Seller drives managed relationship |

|

Type 1: Seller's exchange orientation, buyer's internal orientation. In these situations, it is the seller who is seeking to focus on the longer-term exchange and to provide exchange value to the buyer, whereas the buyer seeks predominantly internal, transactional value. Examples of such a dyadic KRP can be found in the automotive industry, e.g. in the case of Recaro and DaimlerChrysler, where manufacturers built key buying relationships with first-tier suppliers mainly to streamline their internal production logistics processes (e.g. via build-to-order programmes or the co-location of suppliers with plants). The supplier, meanwhile, treats the automotive manufacturer as a key account by providing additional offering benefits (e.g. by managing the whole logistics and ‘safety inventory’ process of an integrated JIT system for the manufacturing plant) (Dyer and Hatch 2006; Howard et al. 2006).

In such cases, it is the task of the seller to move the buyer from an internal to an exchange value orientation. One possible way for the seller is a re-interpretation of the exchange value as focusing on cost reduction of the exchange via better supplier know-how and quicker time-to-market cycles (Cannon and Homburg 2001), in line with the efficiency aim of the buyer. Furthermore, the seller can build risk-reducing benefits into their offering, e.g. upgrading their product/service offering to ‘solutions’, which provide long-term, structural benefits for buyers and seller. Newman's concept of ‘cross-sourcing’ (1989) can also be actively employed by the seller, e.g. by providing a sourcing consortium, in line with Möller and Törrönen's (2003) emphasis on the ‘supplier-network function’.

Type 2: Buyer's exchange orientation, seller's internal orientation. This represents the flip-side of the type 1 posture: the seller establishes KAM programmes for internal efficiency purposes, while the buyer focuses on providing exchange benefits to the seller through a KSM. Examples for such a dyadic posture can be found in situations where the consumer demand-oriented product life cycle management is heavily linked to supply chain management competences (Jüttner et al. 2006). In such a case a buying company would want to provide added value to its suppliers (e.g. customer knowledge transfer) in order for them to assist in competence development and optimized product life cycles. However, this is not always directly reciprocated by these suppliers with an aligned KAM value strategy, often causing them to unilaterally focus on internal efficiency gains.

The focus in type 2 cases is on reducing the seller's perceived risk of deepening the relationship (e.g. risk of dependency on key customers), by relating the exchange value for the seller to the network context (Ehret 2004). This can, for example, be done by providing supplying companies with long-term contracts, supply bundling and supply complimentarity offers, or through joint interaction process development to induce the development of their KAM strategy from an internal to an exchange focus.

Type 3: Seller's exchange orientation, buyer's relational orientation. While the customer in this scenario is interested in generating collaborative relationships, the KAM focuses on exchange value to the buyer. For example, providers of smart phone operating systems such as Microsoft and Symbian (and to a lesser extent, Apple) are currently trying to provide added benefits in terms of implementation/pre-configuration value to some of their core customers in mobile phone production (e.g. Sony Ericsson) and mobile phone distribution (e.g. Carphone Warehouse) in order to become a standard operating system for a newly developing market. The mobile phone manufacturers, meanwhile, are interested in a more collaborative value strategy as part of their new product development (NPD) efforts, e.g. by developing new applications together with their key suppliers to increase the penetration of smart phones in the end-consumer market. This mismatch can potentially be explained by what has been called the distinction of ‘know-how’ compared with ‘capacity’ projects: while the supplying software companies think of their key customers as part of a ‘capacity exchange’ aimed at providing incremental value improvements, the phone manufacturers look for ‘know-how exchanges’ via utilizing supplier knowledge through an integrative partnership (Wagner and Hoegl 2006).

While type 3 postures structurally favour the buyer, they may nevertheless frustrate the customer's key supplier programme as the exchange does not create the added benefits of relational value as expected because of sellers not realizing potential collaborative interactions. Therefore, one would expect the buyer to mobilize the inherent potential of its key supplier programme via an emphasis on relationship value, especially personal interactions (Ulaga 2003). Furthermore, it can be hypothesized that buyers will encourage (and potentially give incentives to) joint process or NPD innovations, maybe based on co-location agreements or joint ventures. Certain ICT-based relationships (JIT, KANBAN systems) could also encourage the supplier company to engage in a deeper and collaborative exchange (Myhr and Spekman 2005). It is also possible to achieve this by incorporating the supplier company into the wider key network of the buying organization (Ojasalo 2004).

Type 4: Buyer's exchange orientation, seller's relational orientation. In this situation, the supplier is interested in collaborative relationships, while the customer is focusing on exchange value, e.g. to retain a key supplier. Consider the example of the discount retailer ALDI and a small manufacturer of breakfast cereals. ALDI is focusing on the exchange value that comes about through the production of standard cereals as retailer brands, while the manufacturer sees retailer brands as a means to create collaborative relationships with ALDI and thus to promote other manufacturer brands. It is likely that the supplier of cereal products will seek to adapt its key account programme as a means to developing deep and collaborative exchanges necessary for a real relational value strategy, i.e. a natural fit. In this case, key account managers will have a kind of pedagogical role towards the customer, aiming at interpreting and displaying interest for the customer to develop different kinds of collaboration. This necessitates a deep knowledge of the customer's value chain and strategy (Jüttner et al. 2006). The key account manager will certainly have to reassure the customer about the costs of such a relational value strategy (e.g. through risk-reducing measures). The move from the customer's exchange orientation to a relational orientation must be supported by a clear exposé of the benefits for the customer: enhanced value created for the customer, respect of confidentiality, low cost of implementation, etc.

Conclusion

This paper develops an initial conceptual grounding regarding value dimensions and strategies in dyadic business-to-business exchanges that are perceived to be of strategic importance to both exchange partners. As such, it specifies some of the more general findings in Henneberg et al. (2005), Möller (2006), and Möller and Törrönen (2003). For this purpose, we have introduced the core explanandum of the key relationship programme as a special case of close and collaborative dyadic exchanges. Based on the dimensions of value creation and appropriation within an exchange environment, we use a multi-faceted perspective of value available to each exchange partner: proprietary value, exchange value and relational value. The explicit incorporation of internal KAM and KSM value elements provides further elaborations of existing literature in this area. These dimensions allow for the derivation of three corresponding key relationship value strategies open to buyers and sellers: an internal value strategy, an exchange value strategy and a relational value strategy.

However, within a dyadic KRP choices regarding these value strategies cannot be made autonomously without taking into account the value orientation of the exchange partner. Using the three key relationship value strategies for buying and selling companies, we conclude that nine generic postures exist within a KRP. While three constitute a natural ‘dyadic match’, two are deemed potentially non-viable. The majority (four postures) depend on the value dyad to be managed in order to achieve a long-term and viable value exchange. This finding leads us to the introduction of ‘dyadic competences’ which are necessary to build these managed relationships. We posit that this will be the case if ‘strategic matching’ is achieved as part of the management of focal net relationships, underpinned by competences which reside in the interactions/activities and shared resources between both companies (Alajoutsijärvi et al. 1999; Möller 2006). As such, we specifically clarify the value appropriation and creation strategies in dyadic key relationship programmes and so contribute to a better understanding of value within deep business relationships, which was singled out by Lindgreen and Wynstra (2005) as one of two important research avenues regarding the value concept in business markets.

The contribution of this paper stems from four different sources. First, our value point of view allows us to clarify the idea that a key relationship programme must be seen as a set of different value-creation strategies, including internally focused ones. KRPs cannot be considered as a homogeneous set, but much more as a portfolio of different value strategies. Second, and contrary to much of the earlier work on value, our departure point is the one of ‘value in and by the relationships’ (Pardo et al. 2006). This means that we are considering value both from supplier and customer perspectives in an integrated (dyadic) manner. Third, our work supports the idea that relational value (the most efficient value strategy) cannot be disconnected from a dyadic perspective in the sense that it results from a combination of both customer's and supplier's resources. Finally, our work points to the fact that specific competences and strategic insights of actors engaging in key relationships are necessary. These competences are not the ones that are mobilized to build the KRP, but more specifically relate to match the customer's and the supplier's value strategies in order to make the relationship viable, sustainable and develop further. These competences, ranging from the knowledge of the exchange partner's position in the value strategy matrix to the ability to incentivize an exchange partner's evolution towards a relational strategy, are complementary and ongoing competences that people in charge of KRPs must display (whether as key account managers, key supplier managers, or the heads of key relationships divisions). As such, our work on how dyadic relationships between companies are affected by value strategies and their matching contributes to a better understanding of networked marketing entities (Achrol 1997; Achrol and Kotler 1999) that are characterized by collaborative interactions as a foundation of marketing management (Vargo and Lusch 2004).

Nevertheless, we recognize that as a conceptual proposal, our work displays several obvious limitations. At present it lacks empirical evidence, and has not been verified in managerial actions. Further research is necessary to develop our multi-faceted value concept in key relationships. Initially, the underlying value strategy constructs need to be operationalized. The overall model must be tested empirically, and work carried out to identify more clearly those additional ‘dyadic’ competences thought to support specific value strategy postures. For example, it remains to be seen whether or not non-viable dyadic postures actually exist and for what reasons they may be perpetuated. In addition, the performance relations of the different postures must be clearly established, particularly the effect on profitability obtained, and the impact of ‘managing’ certain KRPs. While a development from more internal to fully relational dyadic value strategies is implied, it may be that such a development is not in the interest of all exchange partners (barriers and limits to development), is suboptimal (inefficient development), or does not contribute to the overall profitability of the key relationship (short- as well as long-term bottom-line impact).

The impact of a portfolio of value postures and strategies within several key relationships also remains to be analysed in more detail, as does its relationship with different organizational forms of KAM and KSM programmes. This would contribute towards redressing the current imbalance in research where the focus tends to be on explaining organizational performance through entity-specific constructs, and rather neglecting relationship characteristics and network participation as crucial explanatory variables (Gulati et al. 2000). Furthermore, a true network perspective needs to be adopted by putting the dyadic relationships into a systemic environment (Håkansson et al. 1999) which makes it possible to ascertain the necessary networking competences to manage the proposed value strategies within complex inter-organizational structures of exchange relationships (Ritter 1999). The degree to which certain aspects of the key relationship postures and associated value strategies are relationship-specific or can be used cross-relationally remains open to further research (Ritter and Gemünden 2003; Ritter et al. 2004).

Notes

© of Journal of Marketing Management and is the property of Westburn Publishers Ltd or its licensors. This article has been reproduced by EBSCO under license from Westburn Publishers Ltd.

1 Note that a ‘managed relationship’ does not imply ‘managing a relationship’. A managed relationship points towards the fact that dyadically, i.e. by mutual understanding, both parties in the relationship can contribute to making a relationship viable in a concerted way. This can be contrasted with managing a relationship which is about one party attempting to frame the modalities of a relational interaction (Ford et al. 2003).