The appropriateness of the key account management organization

Abstract

Key account management programmes often lack efficiency and effectiveness, as most key account management organizations are inadequately designed for specific customer–supplier relationships. In this paper, a decision model based on transaction cost economics is developed that allows for individualized decisionmaking on the most appropriate key account management organization: by defining the transaction cost economics determinants uncertainty and frequency in more detail companies will become able to refine their decision on the key account management organization alternatives with respect to the characteristics of their individual customer–supplier relationship.

Inefficiencies and ineffectiveness of key account management programmes

Since the late 1960s and early 1970s, key account management (KAM) has belonged to the most popular concepts in marketing management, which suggests serving important customers specifically (Weitz and Bradford 1999), i.e. differently from ‘ordinary’ customers. Over the years, research in KAM has predominantly focused on the objectives and structure of KAM (Kempeners and van der Hart 1999; Pardo 1997; Shapiro and Moriarty 1982, 1984a/b), the selection of key accounts (Gosselin and Bauwen 2006; Napolitano 1997), and only recently on performance issues in KAM (Boles et al. 1999; Homburg et al. 2002; Ivens and Pardo 2007; Pardo et al. 2006). The economics of KAM, i.e. the mechanisms determining why and when to implement as well as how to organize KAM in specific business relationships, has merely been of implicit interest in previous research and neglected so far.

This lack of research in the economics of KAM is accompanied by a rather remarkable anachronism: though various empirical studies report poor efficiency and effectiveness of most KAM programmes (e.g. Napolitano 1997; Sengupta et al. 1997), Wengler et al. (2006) find in an exploratory study that more than 20% of the 91 interviewed companies from diverse industries (e.g. telecommunication, mechanical and electrical engineering, chemical, and the automotive industry) still plan to implement KAM, while more than 50% have already implemented KAM. These findings therefore suggest that the popularity of KAM is still rather strong – despite the empirical findings that added value will be difficult to extract from most KAM programmes. Only as soon as the intensity of competition and/or the intensity of coordination between supplier and customer increases does KAM seem to be the most appropriate marketing management organization alternative (Wengler et al. 2006).

A model will be proposed in this paper that will help in the process of choosing the most appropriate KAM organization with respect to the characteristics of a specific customer–supplier relationship. Based on transaction cost economics reasoning, the model allows for a qualitative assessment of various KAM organization alternatives and will thereby support the decision on the most appropriate one. Before laying out the decision model, the questions regarding what is understood by KAM and how the concept fits in recent marketing management research need to be defined.

The concept of key account management

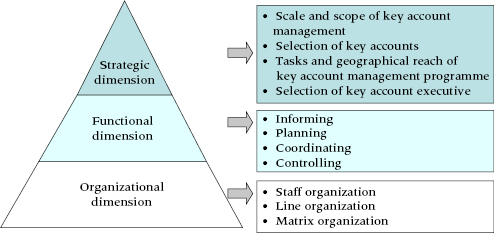

Key account management is considered as a focused, supplier relationship marketing programme (Weitz and Bradford 1999) which aims at establishing, developing and maintaining a successful and mutually beneficial business relationship with the company's most important customers. KAM embraces strategic, functional and organizational dimensions – see Figure 1.

Figure 1 The dimension of KAM

The strategic dimension of key account management

As KAM takes on an important part within the company's marketing management, it needs to know which strategy it has to follow: depending on the corporate or business strategy as well as the key account itself, KAM has to develop an individual marketing concept for each key account (Sheth et al. 2000), a concept that encompasses the scale and scope of KAM, the selection of key accounts, tasks and geographical reach, as well as the selection of a KAM executive and a KAM team.

The functional dimension of key account management

The formulation of the tasks within the functional dimension of KAM is the result of its strategic objectives. This includes all customer-oriented tasks that are necessary to reach the strategic goals, i.e. informing (Weilbaker and Weeks 1997), planning (Pegram 1972), coordinating and controlling.

The organizational dimension of key account management

After the KAM programme strategy is set and its tasks are formulated, the company needs to consider its institutionalization (Shapiro and Moriarty 1984a). The complete KAM programme has to be reflected by its formal organization (Grönroos 1999).

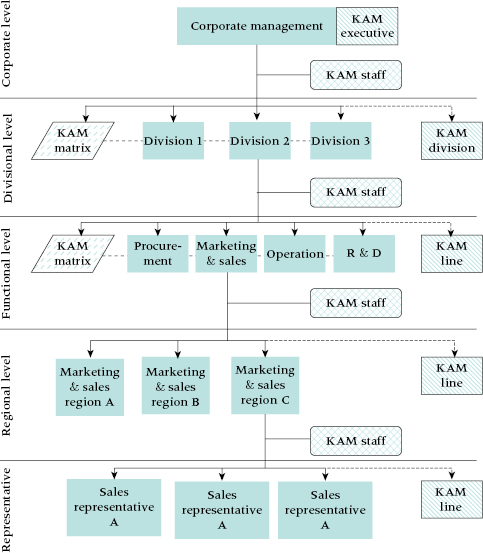

Within organizational science, researchers differentiate between three general organizational principles: the staff organization, the line organization and the matrix organization (Schreyögg 2003), which can all be applied to KAM. KAM as a staff organization takes on a more supportive role by specializing in analysing, planning and controlling; in contrast, KAM as a line organization will be more appropriate if a self-responsible KAM unit is desired, which manages its customers by itself and influences the internal coordination processes considerably. KAM as a matrix organization is established – at the least – alongside two dimensions, e.g. the customer and product management, and is thus very powerful, but often characterized by internal conflicts.

As companies are also characterized by hierarchies, these organizational design alternatives might be implemented on different organizational levels (Shapiro and Moriarty 1984a), i.e. the level of the sales representative, the regional level, the functional level, the divisional level or the corporate level – see Figure 2.

Figure 2 Alternative organizational designs of KAM

At which of these organizational levels KAM is implemented depends on the marketing management of the supplying company as well as the individual characteristics of each supplier–customer relationship. It is therefore necessary to appreciate KAM as a relationship marketing programme – and not solely as a personal selling approach, as it had been considered until the 1980s (Wotruba 1991).

Key account management in the context of relationship marketing

The insistence on shifting the focus of KAM from personal selling to relationship marketing (Weitz and Bradford 1999) considerably alters KAM's character: it overcomes the limiting aspects of personal selling and allows for analysing and managing KAM with an awareness of its wider context – a business-to-business relationship. Therefore aspects completely neglected so far in KAM research, such as its implementation or its adequate design with respect to the business relationship, have become more relevant in KAM research.

In business-to-business markets, the marketing function often seeks to fulfil the needs and desires of each individual customer; companies are increasingly focusing their resources on their most profitable customers and are starting to implement the adequate organizational structures to fully integrate all customer-facing activities (Sheth et al. 2000). KAM is one structure, but the most expensive alternative for designing the supplier–customer interface, and its implementation may be less attractive than has been generally thought (Piercy and Lane 2003). It is therefore a strategic investment decision that needs to be evaluated carefully in advance (Blois 1997).

As the organizational design of the marketing management organization and, in our case, the KAM programme are predominantly determined by internal as well as external factors (Webster 2000), we need to turn to an economic theory that enables us to derive relevant decision determinants and to evaluate organizational alternatives based on their economic value. Although both economic theories, the resource dependence approach (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978) and the network approach (Hakansson 1982; Sydow 1992), allow for an analysis of supplier–customer business relationships, neither encompasses both perspectives simultaneously in their economic analysis, the intra-organizational as well as the inter-organizational perspectives (Schreyögg 2003). In addition, both theoretical conceptions lack a comparative, economic approach on choosing between organizational alternatives.

In the following, we will turn to transaction cost economics, because it focuses on the economic exchange process and the internal organization, and offers a powerful economic theory approach based on transaction costs as well as a comparative cost calculation based on a qualitative assessment that is needed for choosing the most appropriate KAM organization.

Transaction cost economics and marketing management

Transaction cost economics (Williamson 1975, 1985, 1996) is traditionally concerned with the analysis and the evaluation of the most efficient organizational mode of completing and executing a transaction or a related set of transactions – on the basis of transaction costs (Williamson 1975).1

Transaction cost economics differentiates mainly three organizational arrangements by which exchanges can be carried out: firms (hierarchies), markets and bilateral governance (hybrids). Based on the transaction costs resulting from the transaction's asset specificity, uncertainty and frequency, the agent will choose the most efficient organizational arrangement. The efficacy of the alternative organizational mode (firm, market or bilateral governance) must be assessed thereby in a comparative analysis. ‘Which transactions go where depends on the attributes of transactions on the one hand, and the costs and competence of alternative modes of governance on the other’ (Williamson 1996).

Although Williamson was convinced that bilateral governance would be of neglible relevance, as he assumed the hybrid economic organization to be inherently unstable and difficult to organize in the presence of uncertainty and transaction-specific assets (Williamson 1975), his reservations vanished over time (Williamson 1985, 1996), and he acknowledged that these hybrid economic organizations might even pose interesting organizational problems.

Within bilateral governance, such an organizational problem particularly arises as soon as two autonomous agents strive for the establishment of a long-term relationship with their transaction partner. Depending on the scale and scope of the business relationship as well as their activities, the supplying company needs to decide on the organization and design of its marketing management. Even though these intra-organizational aspects are increasingly determining the efficacy and success of business relationships, transaction cost economics has disregarded the relevance of the internal organization in intermediate market exchanges so far (Theuvsen 1997). With its three determinants (i.e. asset specificity, uncertainty and frequency) transaction cost economics is merely able to decide on the transactional arrangement, but not on the intra-organizational design of each of these arrangements – depending on the transaction's situational factors.

The decision on the most appropriate marketing management organization is therefore different from traditional transaction cost economics considerations as it does not represent any of the governance modes, i.e. market, bilateral governance or hierarchy. Applying transaction cost economics analysis to such internal organizational matters as the decision between alternative marketing and sales organizations therefore requires an extension of traditional transaction cost reasoning. For such a comparative institutional approach, wherein the most efficient marketing organization can be chosen, further determinants are necessary to enable informed choices among these complex alternatives. Particularly, the transaction characteristics uncertainty and frequency seem to play a key role in this context and may help to determine the most efficient marketing organization design – with respect to a specific business relationship.

The determinants of the decision model

Extending the focus of transaction cost economics research to intra-organizational design matters, such as the decision on the appropriate marketing management organization, will require a detailed analysis of the relevant transaction characteristics (1) asset specificity, (2) uncertainty and (3) frequency. In the following sections, we will demonstrate that, besides asset specificity, uncertainty and frequency are also of particular relevance in the decision on the appropriate organizational design (Joshi and Stump 1999a; Menard 2004) as the embeddedness of the company, i.e. its institutional environment, increasingly matters (Cannon and Perreault 1999; Li and Nicholls 2000; Williamson 1996).

Asset specificity

Asset specificity has traditionally played a major role in transaction cost economics. Williamson is particularly concerned with transactions which involve a high degree of asset specificity, as companies need to economize on the latent hazards of opportunistic behaviour (Heide and John 1990; Klein 1996). Depending on the degree of asset specificity, Williamson proposes different organizational arrangements for the execution of transactions, i.e. the market, bilateral governance or firm.

Recent research in transaction cost economics, however, finds that asset specificity does not necessarily need to result in an asymmetrical commitment of a transacting party within a business relationship (Ganesan 1994; Heide and John 1990; Joshi and Stump 1999a). Due to such relational institutions as private ordering, credible commitment and relational norms, opportunistic behaviour might be attenuated in relational exchange situations. An effect similar to those relational institutions might also have the implementation of a specific marketing management organization (e.g. key account management): though it increases the supplying company's asset specificity on the key account, since it needs to be seen as an investment in the business relationship (Blois 1997), KAM facilitates the control of the customer's behaviour and reduces – due to its closeness – the hazards of opportunistic behaviour.

In the presence of asset specificity, the implementation of a specific marketing management organization might thus be helpful. Within the transaction mode of bilateral governance there will be various design alternatives of such a marketing management organization that will primarily depend upon the scale and scope of the business relationship's asset specificity. For reasons of simplicity, we will suppose in the following a middle to high degree of asset specificity that requires the implementation of KAM; this assumption will enable us to show how the design of the KAM organization will vary, depending on the company's perceived uncertainty and frequency.

Uncertainty

In his approach on transaction cost economics Williamson (1996) simply assumes a certain, but constant, degree of uncertainty and acknowledges three main forms of uncertainty, namely primary uncertainty, secondary uncertainty and behavioural uncertainty. The distinction between primary and secondary uncertainty can be traced back to Koopmans (1957). From Koopmans' perspective, uncertainty consists of aspects that are unpredictable and take the agent by surprise, i.e. primary uncertainty, as well as aspects that can be influenced by the economic agent, i.e. secondary uncertainty. Even though both forms of uncertainty can be considered equally important (Koopmans 1957; Williamson 1996), only secondary uncertainty issues appear to be relevant in the decision on the appropriate marketing management organization, as these issues can be influenced and are more predictable: they will include internal organizational issues as well as external factors, like the institutional environment or current market characteristics surrounding the transaction/relationship (Joshi and Stump 1999b; Windsperger 1998).

Drawing from recent research in marketing and organizational science, our assessment of sources of uncertainty reveals four uncertainty clusters:2 (1) intra-organizational complexity, (2) environmental complexity, (3) environmental dynamics and (4) interdependencies.

By a more in-depth differentiation of secondary uncertainty, it is possible to make this term more explicit, instead of leaving it as abstract as it has been within transaction cost economics so far. Clustering these sources of secondary uncertainty into intra-organizational complexity, environmental complexity, environmental dynamics and interdependencies also improves the analysis from the perspective of marketing management.

Besides primary and secondary uncertainty, behavioural uncertainty is rather important within transaction cost economics. In the context of opportunistic/strategic behaviour, behavioural uncertainty mainly determines adequate governance structures to safeguard the economic agent with the transaction-specific assets against the expropriation hazards (Williamson 1996). The design of a specific marketing management organization may constrain the customer's strategic behaviour as intensified coordination and collaboration efforts make strategic behaviour – and thus behavioural uncertainty – more unlikely.

Uncertainty in all its facets therefore influences the design of the internal marketing management organization. Besides uncertainty, frequency also impacts the internal organizational design of KAM and is thus of higher relevance than transaction cost economics has suggested so far.

Frequency

The third determinant of Williamson's transaction cost economics approach, besides asset specificity and uncertainty, is frequency. From the traditional perspective on transaction cost economics, Williamson assumes frequency as a relevant, but not necessarily decisive, determinant. The transaction costs decrease if the transactions are of a recurrent kind. Williamson does not emphasize the relevance of frequency, but instead supposes a middle degree of frequency in bilateral governance (Williamson 1996).

Frequency, however, plays a more dominant role than transaction cost economics has suggested so far: transactional exchange applies only to pure or almost market transactions. Particularly in recent decades the character of most economic exchanges has changed from a transactional to a more relational one, which means that transaction cost economics needs to consider the business relationship (Kleinaltenkamp and Ehret 2006). The transaction cost economics determinant frequency will then include (1) the number of transactions of a recurrent kind, which are part of a single market transaction, (2) the number of market transactions, which are characterized by their interconnectedness, and (3) the key account's relational intent.

The economic agent's relational attitude, also called relational intent, has gained considerable attention in recent articles on relationship marketing (e.g. Ganesan 1994; Kumar et al. 2003; Pillai and Sharma 2003). The relational intent is thereby defined as the ‘willingness of a customer to develop a relationship with a firm while buying a product or a service attributed to a firm, a brand, and channel’ (Kumar et al. 2003). The relational intent is often accompanied by various relationship-building activities (e.g. informal information exchange, meeting of corporate members, etc.) which are realized in addition to and outside of the ordinary market transactions. Responding to these activities implies additional transaction costs for the supplying company: depending on the relationship-building activities as well as the marketing organization design, the transaction cost economizing effects will vary. From a transaction cost economics perspective, relational intent therefore indicates how efficiently the organization may be able to handle, or rather respond, to the relationship-building activities of the buying company. As the resulting transaction costs are mainly determined by the frequency of interaction, relational intent therefore needs to be recognized as a separate but relevant decision determinant within the traditional transaction cost determinant frequency.

In contrast to its traditional understanding, in the context of business relationships, frequency comprises more than the number of transactions. In addition, the determinant includes the number of market transactions as well as the customer's relational intent.

In the previous section, the main determinants in transaction cost economics (i.e. asset specificity, uncertainty and frequency) were extended and defined in more depth. As the analysis of these variables in the context of the design of the marketing management organization has demonstrated, asset specificity, which primarily determines the transaction cost economizing governance mode, remains an important factor, as it mainly influences the mode of the marketing management organization; but transaction cost determinants, uncertainty and frequency, become more important in the context of the intra-organizational design, like the decision on the adequate marketing management organization, and mainly determine the design of these internal organizations.

The decision on the most appropriate KAM organization

The decision on the most appropriate KAM organization consists of a two-step procedure. In the first step, the economizing effects, i.e. the efficiency of the KAM organization alternatives, needs to be determined; the second step, the cost–benefit assessment, in which the transaction cost economizing effects are weighed against the set-up costs of implementing the organizational alternative, enables the supplier's management to decide on the most appropriate KAM organization. The most appropriate KAM organization alternative therefore is not the most efficient alternative, but the one with the best cost–benefit trade-off.

In the following, (1) the principles and structure of the decision model will be explained, (2) the economizing effects of the KAM organization alternatives will be determined and (3) the cost–benefit assessment will be carried out. However, it is important to notice that the following statements need to be understood as initial conceptual reflections, which are still subject to empirical testing. In addition, the analysis of the economizing effects as well as the cost–benefit assessment will remain rather abstract, as the decision can be best made with respect to a specific supplier–customer business relationship.

The principles and structure of the decision model

In transaction cost economics, traditional decision-making is largely based on comparative analyses. Although researchers in transaction cost economics are increasingly trying to quantify transaction costs as well as to develop complex mathematical models (Anderson 1996), Williamson stays in the tradition of transaction cost economics and in his analysis of the institutions of governance – referring to Simon (1978) – compares the transaction cost economizing effects of his alternative governance modes. This way, all governance modes are compared simultaneously and in relation to each other (Williamson 1985, 1996); therefore the quantity of transaction costs is not decisive, but rather the transaction cost economizing effects of each of these governance modes. We will follow Simon and Williamson in their approach and favour a comparative decision model – based upon the extended transaction cost economics decision determinants.

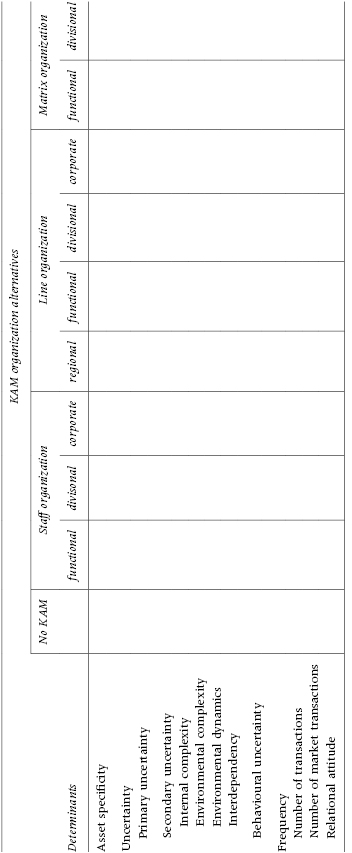

For the decision model, we will focus completely on the economizing effects of different KAM organizations and describe all the other alternatives as ‘no KAM’. With regard to the above mentioned KAM alternatives, we suggest ten decision alternatives that are rather common in the context of KAM. There are four basic decision alternatives: no KAM organization, a staff KAM organization, a line KAM organization, and a matrix KAM organization; depending on the organizational level (regional, functional, divisional, corporate), variations of these basic decision alternatives are conceivable.

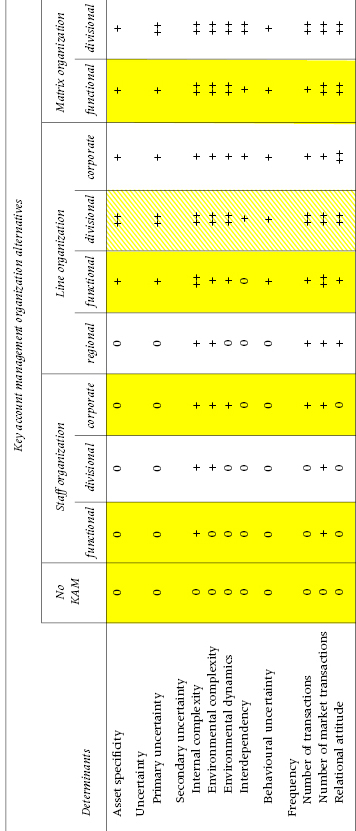

The decision model is structured rather simply – see Table 1. It consists of two dimensions, the alternative KAM organizations as well as the relevant transaction cost economics determinants. These consist of the determinants asset specificity, uncertainty and frequency – as Williamson's approach suggests. Asset specificity will not be of high relevance in our model as we assume a middle to high degree of asset specificity, which requires the implementation of KAM. More important to the decision process is the determinant uncertainty: it will be distinguished between primary, secondary and behavioural uncertainty. The dominant role of secondary uncertainty within the decision model becomes evident as it is categorized in its four sources of uncertainty, i.e. internal complexity, environmental complexity, environmental dynamics and interdependency. The third determinant of transaction cost economics, frequency, will include the number of transactions, the number of market transactions and the customer's relational intent.

Table 1: The structure of the decision model

Whereas the relevant transaction cost economics determinants represent the vertical part of the decision model, the KAM organization alternatives correspond with the horizontal part.

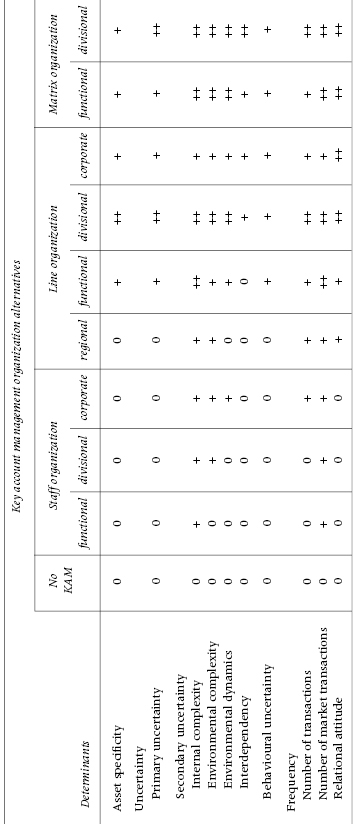

The economizing effects of the KAM organization alternatives

The following transaction cost economics analysis of the ten marketing management organization alternatives reveals the transaction cost economizing effects of each alternative. Whereas ‘no key account management’ means that there will be no economizing effects at all and should be proposed only if there is no asset specificity, uncertainty and frequency, KAM as a staff organization allows for various economizing effects; at the functional as well as the corporate level, staff KAM represents a centralized planning and coordination unit. At the functional level, i.e. as a part of the marketing and sales function, strategic management processes and procedures are centrally coordinated across the regional marketing and sales units, whereas operational customer service is as decentralized as possible. The same is true for ‘staff key account management’ at the corporate level, though the coordination takes part across divisions, requires massive support from the corporate management, and is better equipped for dealing with – besides internal complexity – environmental complexity and environmental dynamics. As soon as a company prefers to centralize the strategic aspects of KAM and to leave operational tasks such as serving the key account within the marketing and sales function, the company should decide for staff KAM at the divisional level, which economizes partly on internal and environmental complexity.

In contrast to staff KAM, which represents a separate unit external but still partly attached to the line organization, ’line KAM’ is fully integrated within the company's organization. ‘Key account management as a line organization at the regional level’ is the lowest-level KAM programme within the line organization, and economizes best in situations with medium internal coordination needs and partial external integration within an existing business relationship, while the product portfolio does not require any major adjustments. Concerning ‘key account management as a line organization at the functional level’, the decision alternative seems to be a particularly appropriate choice in business relationships if the key account requires – to a certain extent – a customization of the supplier's product-service offerings.

From a hierarchical point of view, KAM is equally as powerful as the other organizational functions and may thus be able to influence these functions in favour of the customer's requests. However, the transaction situation should be characterized by only a medium degree of environmental complexity, environmental dynamics, behavioural uncertainty and relational attitude. ‘Key account management as a line organization at the divisional level’ is exceptional within the decision alternatives as it represents a separate and independent business unit in the corporation. This organizational alternative should be pursued only in those transaction situations characterized by a completely distinct product-service offering for one or a small group of important customers. ‘Key account management as a line organization at the corporate level’ is represented by a member of the management board. The key account alternative's economizing effects on asset specificity as well as on uncertainty are characterized by a medium degree, due to its limited involvement in KAM's day-to-day-business (see Table 2). Instead, ‘key account management as a line organization at the corporate level’ is best suited for transaction situations in which the key account requires specific treatment at the board level, but not at the operational level of the business relationship.

Table 2 The economizing effects of KAM organization alternatives

A more adequate KAM alternative for high-frequency and high-involvement business relationships in dynamic and interdependent market environments is represented by the matrix organizations of KAM. ‘Matrix KAM’ at the functional level seems to be the best alternative if the intense business relationship is characterized by a highly competitive environment where product and process adjustments are often required, and the key accounts are both demanding but also rather valuable for the corporation. The economizing effects of ‘key account management as a matrix organization at the divisional level’, however, are the most powerful, as this KAM alternative moves the supplying corporation close to a quasi-integration without setting up a completely distinct business unit. Its internal processes are fully capable of enacting transaction cost economizing in situations characterized by high environmental complexity, high environmental dynamics and high interdependency.

The assessment of alternative KAM programmes from a transaction cost economics perspective reveals their comparative advantages and disadvantages in different transaction situations (see Table 3). Although we are now able to decide on the most efficient transaction cost economizing organization – with respect to specific transaction situations – our assessment of the economizing effects of the various KAM alternatives has so far neglected the (somewhat vast) costs of implementing these alternatives. For a comprehensive discussion, management needs to assess not only the benefits (transaction cost economizing effects) but also the costs (set-up costs) of implementing one of these decision alternatives (Blois 1996). Only if the trade-off between the benefits (transaction cost savings due to efficient information processing, etc.) and the costs (e.g. costs of implementation, costs of organizational resistance, etc.) is positive may altering or adjusting the marketing management organization's design or setting up a new organizational design be sensible (Windsperger 1996).

Table 3 The transaction cost economizing effects and the relevance of KAM alternatives

Cost–benefit assessment of the KAM organization alternatives

The assessment of the costs and benefits will permit decisions on the relevance and irrelevance of each KAM alternative, as some of the KAM alternatives would require massive investments/costs for realigning processes and/or might induce organizational resistance. We are therefore able to exclude several alternatives on the basis of a theoretical assessment: ‘staff key account management at the divisional level’ lacks influence across functions and has conflicting interests, particularly with the marketing and sales function; ‘line KAM at the regional level’ does not have sufficient authority concerning cross-functional coordination as long as it remains organized within the existing sales force; ‘key account management as a line organization at the corporate level’ guarantees top-management involvement in the KAM process, but is completely detached from operational activities; and finally, ‘key account management as a matrix organization at the divisional level’ requires enormous implementation effort and costs necessary for setting up a functioning, cross-divisional KAM programme.

A positive benefit–cost trade-off, however, might be achievable in the context of the other KAM alternatives: ‘no key account management’ requires no implementation costs at all; the functional as well as the corporate ‘staff key account management’ enable the company to achieve considerable coordination synergies across the marketing and sales function or the divisions' KAM programmes, respectively; ‘line key account management programme at the functional level’ represents a sole, but powerful, organizational unit detached and independent of the marketing and sales function; ‘matrix key account management at the functional level’, though rather expansive, represents the most adequate and efficient alternative in dynamic market environments; ‘line key account management at the divisional level’ represents rather an exception, since these organizations might be cost efficient as well as effective, but only in rare situations.

As the preceding cost–benefit assessment has revealed, some KAM organization alternatives are more relevant than others. One needs to keep in mind that the ‘relevance’ of these organizational alternatives has been determined on a very abstract level.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a decision model on the adequacy of the design of KAM organizations. Based on transaction cost economics, an easy-to-handle decision model has been developed that supports companies in their decision on the most appropriate KAM organization – with respect to their specific customer–supplier business relationships.

The application of transaction cost economics to the analysis of the marketing management organization required two extensions: its application within business relationships and the development of a multi-dimensional concept of uncertainty as well as frequency. Based upon these decision determinants, the proposed organizational KAM alternatives were qualitatively assessed concerning their cost–benefit trade-off, i.e. transaction cost savings minus set-up costs (e.g. costs of implementation/organizational resistance). By evaluating these alternatives, companies will be able to choose their most appropriate KAM organization alternative. In effect, the decision model will also be applicable for reviewing the appropriateness of existing KAM organizations.

Our analysis of the most appropriate KAM organization is the first theory-based approach to making informed choices on various KAM organization alternatives. For too long, KAM research has neglected economic theory, though increasingly researchers have been recognizing the relevance of the economic perspective in KAM (e.g. Homburg et al. 2002; Pardo et al. 2006). Although the economic perspective encompasses both efficiency and effectiveness, the prime focus in this paper is on transaction cost economics, which seems to be rather suitable. First, the decision on the marketing management organization is primarily concerned with the supplier's internal organizational design, i.e. the supplier's efficiency; second, due to the extension of the determinant uncertainty, the customers'/markets' requirements are considered, although indirectly; and finally, recent research by Ivens and Pardo (2007) suggests that KAM does not necessarily increase customer satisfaction or trust.

The application of the decision model is based on initial conceptual reflections. Further refinement of the decision determinants as well as empirical research and testing will be indispensable. A start for more theory-based research in key account management has, however, been made.

Notes

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Journal of Business Marketing, originally Wengler, S. (2007) ‘The appropriateness of KAM organization’, Journal of Business Marketing, 1(4), 253–272.

1 Transaction costs are defined as the ‘costs of running the economic system’ (Arrow 1969), i.e. they include the costs of planning, adapting and monitoring transactions (Williamson 1985).

2 In this paper, complexity will be understood in the following as an antecedent of uncertainty – drawing upon organization theory and its research on complexity for the categorization of complexity.