Developing strategic key account relationships in business-to-business markets

Abstract

In a series of articles and conference papers that stretch back to 1993, the author, individually and with colleagues, has explored the nature of buyer–seller interaction in organizational markets. A number of models evolving from this work have provided the foundation for the work of others in the field, most notably researchers at Cranfield University.

The result has been the development of some powerful models that have been instructive in describing the nature of buyer–seller interaction and the form that relationships take at various stages of their development.

What had been lacking was empirical evidence to link those models in a comprehensive framework that provided clues as to how buyer–seller relationships could be managed. This paper reviews the literature concerning relational development in key strategic account management (KSAM) and reports on a research project that explored how the development of buyer–seller relationships is influenced by the nature of the problems that buyers and sellers focus upon resolving during the process of interaction. This paper thus integrates the Millman–Wilson model of relational development with the problem-centred product, process and facilitation (PPF) model of buyer–seller interaction in business-to-business markets, and provides valuable insights into why and how relationships develop over time. In its revised form the paper also takes account of work that has built on the early models and other work that has contributed to our understanding of relational development.

Introduction

This paper explores the literature concerning the nature and development of key account customer relationships in business-to-business markets. Building upon the work of a number of writers, many from the Industrial Marketing and Purchasing (IMP) Group tradition, it offers a framework for key account management (KAM) that links two previously developed models, the Millman–Wilson relational development model (1994, 1995) and the Product, Process and Facilitation model first posited by Wilson (1993), further explored by Wilson and Croom-Morgan (1993) and Millman and Wilson (1995), and operationalized by Wilson (1997).

Defining key/strategic accounts

Millman and Wilson (1994) defined a key account as a customer in business-to-business markets identified by a selling company as being of strategic importance. Although broad, the value of this definition was that it avoided linking key account status exclusively to considerations of size, geographical spread and volume of business represented by the customer, which dominated earlier definitions (Colletti and Tubridy 1987; Grickscheit et al. 1993). While important, these factors do not encompass the full range of criteria that may be used to establish the strategic importance of a customer.

Early research from Millman and Wilson (1997) suggested a far broader range of selection criteria that was later confirmed in the work of McDonald et al. (1997). The first in the following list was the most frequently cited criterion in the Millman–Wilson (1997) study, typically combined with others, depending on the characteristics of the participant's company and their industry background:

- The Pareto 80/20 rule.

- Size of purchase budget.

- Sales growth potential.

- Customer prestige.

- Account profitability (current and potential).

- The geographical spread of the customer and the potential to gain access to otherwise inaccessible markets.

- Receptivity to developing close long-term relationships.

- Access to new/complementary technology.

- Cultural ‘fit’.

- Strategic ‘fit’.

- Cross-selling opportunities.

- Limited customer base.

The importance of including these factors is their emphasis upon the relational issues, such as the customer receptiveness to developing close long-term relationships and cultural ‘fit’, as well as the transactional issues such as sales and profit potential. Some of these criteria of key account attractiveness were partly confirmed and consolidated into the following categories by McDonald et al. (1997), which, interestingly, did not include consideration of cultural ‘fit’ or customer receptiveness to developing closer relationships with suppliers:

- Volume-related factors.

- Profit potential.

- Status-related factors.

The more relational measures of attractiveness were explored by McDonald et al. in defining supplier attractiveness to the customer in terms of the ease of doing business, product and service quality, and people factors. The importance of these and related relational factors in determining customer attractiveness to sellers reaffirmed earlier research reported later in this paper.

The work of both Millman and Wilson (1994, 1995, 1997) and McDonald et al. (1997) serves to suggest that key accounts may be small or large compared with the seller; operate locally, nationally, regionally or globally; they may exhibit a desire for close long-term relationships or wish to remain at arm's length; or be transactional and adversarial in their dealings with suppliers. What remains critical is that they are perceived as being of fundamental importance to the selling firm in achieving its major strategic objectives.

There is a tendency in the literature to equate the terms national, key and strategic accounts, differentiating only on the basis of geographical spread through the additional descriptor ‘global’. This, in my view, is an error. There is a need to differentiate between accounts that have transactional importance, in that they represent high levels of sales opportunity, and those that have strategic importance in their potential for value creation beyond product or core product offering.

Woodburn and Wilson, in the editorial to this book, imply this distinction by defining strategic key account management as ‘a supplier-led process of inter-organizational collaboration that creates value for both supplier and strategically important customers by offering individually tailored propositions designed to secure long-term profitable business through the coordinated deployment of multi-functional capabilities’.

Gosselin and Heene (2003) distinguish between key account selling and strategic account management. They suggest that strategic accounts are those where there is mutual recognition of the strategic importance of the relationship by both buyer and seller and further suggest that while both key account selling and key account management may be involved in the creation and delivery of value, strategic account management is also concerned with building the competencies upon which that value is based.

This is an important distinction that would save much confusion in the minds of practitioners who still often mistake key account selling for key account management.

First, the transition from customer to key account and then to strategic account would be more easily facilitated, as would a downgrading of the relationship; and second, the clearer definition of client status would encourage the greater involvement of marketing in the analysis of customer relationship potential on a number of different parameters, and also provide a clearer view for senior managers of customer portfolio potential.

It is not entirely in the gift of the supplier to grant strategic account status, although there may be greater leeway in the case of key accounts. There is one other, perhaps overriding qualification: the strategic account, in order to be a strategic account, must perceive the supplier as being a real or potential source of strategic advantage – without that the relationship cannot develop beyond the pre- or early KAM relational states.

Since the late 1970s the literature on key account management appears to have emerged in parallel to, but in many ways quite separately from, the interaction, network and relationship literature, as a result of strong practitioner involvement. It is only relatively recently that academics have turned their attention to the topic and integrated the study of KAM with other bodies of theory, and have thrown valuable light on the operationalization of the principles of interaction, network theory and relationship marketing through KAM processes. The value of this literature, however, is in the descriptions that it provides of KSAM processes and related issues, rather than in the provision of an integrated model that may instruct key account management processes. It is proposed here that the integration of the PPF model with the Millman–Wilson relational development model provides just such a management tool.

Later research outlined elsewhere in this book has dealt with broader issues, but little more recent research has been reported that deals specifically with relational strategies applied at different relational stages in order to increase or diminish relational intensity, although attention has been given to relational development (Woodburn and McDonald 2011) and the appropriate economic organization that may be adopted to facilitate KSAM (Wengler 2007).

A model of relational development

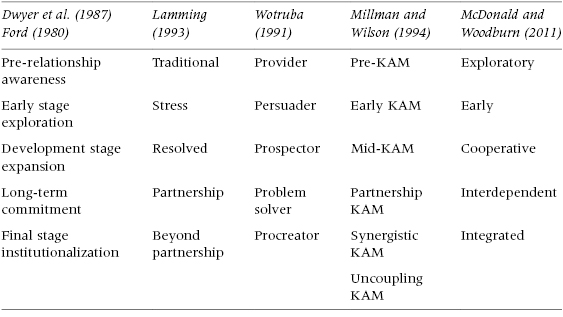

The Millman–Wilson (1994) model was based on exploratory research and concepts drawn from sales strategy (Wotruba 1991), supply chain management (Lamming 1993) and interaction literature (Dwyer et al. 1987; Ford 1980). The model was adopted for further exploration by McDonald and Rogers (1996, 1998) (see Table 1). These early papers from Cranfield used the same descriptors as had been developed by Millman and Wilson, although in later iterations these were changed (e.g. Woodburn and McDonald 2011). The original descriptors are retained here because of the marked similarity between the characteristics identified by the Cranfield research and the original KAM model.

Table 1: KSAM relationship stages in the literature

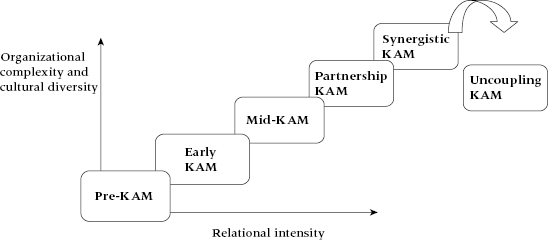

The original KAM relational development model suggested that buyer–seller relationships could evolve through a number of relational states or stages (see Figure 1). Each of these states was characterized by varying degrees of dyadic complexity and relational intensity and each stage represented implications for sales strategists. The aim was to model a number of different relational states that had been observed and to suggest that it was possible to develop relationships from ‘market-based’, adversarial relationships towards closer ‘value-laden’ synergistic relationships, but not to suggest that it was necessary to adopt relational development as the sole KSAM strategy.

Figure 1 KSAM relational development states

Attempting to develop close, trusting value-creating/sharing relationships is one strategic option for KSAM programmes, but in line with Kraljic's (1983) thoughts on supplier portfolios, account management is essentially about portfolio management. Some strategically important relationships may be close, trusting and mutually supportive, but others will be adversarial, market focused and self-interested, remaining at pre, early or mid-KAM states, but may nevertheless be of strategic importance. The model can be described as a hierarchy of relationships, one building progressively upon the other. While this appears to be intuitively attractive there is strong evidence to suggest that relationships may change their ‘state’ quite rapidly, skipping stages or reverting to earlier forms, despite being embedded in strong social relationships, a point endorsed by Woodburn and McDonald (2011).

Characteristics of KAM relational states adapted from Millman and Wilson (1994) are outlined below.

Pre-KAM

Not all customers are potential key accounts. The task facing the sales and marketing function in the pre-KAM stage is to identify those with the potential for moving towards key account status and to avoid wasteful investment in those accounts that do not hold that potential. Pre-KAM selling strategies are concerned with making basic product or service offerings available while attempting to gather information about the customer in order to determine whether or not they have key account potential.

Early KAM

Early KAM is concerned with exploring opportunities for closer collaboration by identifying the motives, culture and concerns of the account, with targeting competitor strengths and weaknesses, and with persuading customers of the potential benefits they might enjoy as ‘preferred’ customers. A detailed understanding is required of the decision-making process and the structure and nature of the decision-making unit, as well as the buyers' business and the problems that relate to the value-adding process.

At this stage, tentative adaptations will be made to the seller's offer in order to more closely match buyer requirements. The focus of the sales effort will be on building trust through consistent performance and open communications.

Key account managers will need to demonstrate a willingness to adapt their offering to provide a bespoke solution to the buyer's problems. High levels of uncertainty about the long-term potential of the relationship may mean that they will need to promote the idea for non-standard product offerings into their own company. Where these attempts are unsuccessful, then ‘benefit selling’ and the level of personal service provided by the salesperson may serve to differentiate the seller's offer.

Mid-KAM

As the relationship develops, so do levels of trust and the range of problems that the relationship addresses. The number of cross-boundary contacts also increases, with the salesperson perhaps taking a less central role. The account review process will tend to shift upwards to senior management level in view of the importance of the customer and the level of resource allocation, although the relationship may fall short of exclusivity and the activities of competitors within the account will require constant review.

Partnership KAM

Partnership KAM represents a mature stage of key account development. The supplier is often viewed as an external resource of the customer and the sharing of sensitive commercial information becomes commonplace as the focus for activity is increasingly upon joint problem resolution.

Synergistic KAM

At this advanced stage of maturity, key account management goes ‘beyond partnership’ when there is a fundamental shift in attitude on the part of both buyer and seller and they come to see each other not as two separate organizations but as parts of a larger entity creating joint value (synergy) in the marketplace.

Uncoupling KAM

Dissolution of a KAM relationship tends to be viewed in a pejorative way, as though a ‘successful’ relationship is by definition one of long duration. While in most cases buyers and sellers may perceive benefits in developing long-term relationships, we have uncovered some short-term relationships deemed to be successful by the participants and many others which, with the benefit of hindsight, were ill conceived.

As Low and Fullerton (1994) remind us: ‘Deciding when to get out of an existing relationship and into a new one would minimize the substantial economic, political and emotional cost associated with building a relationship that was never destined to last’. In essence, many relationships are propped up beyond their relevance, or some event precipitates their termination, suggesting the need for an uncoupling process and contingency planning.

Dissolution, or uncoupling KAM, was ignored in the later development of the model by McDonald and Woodburn (2011) but its importance is emphasized by the observation that companies developing supplier relationships perceive three relational states (Moeller et al. 2006): those without suppliers, which are essentially geared to assessing their potential to be in suppliers (this broadly equates to pre/early KAM); those relationships within suppliers are focused upon collaborative co-creation of value (a number of stages are identified: set-up, development, contract and disturbance management which broadly equate to the processes involved in mid/partnership/synergistic KAM); and in supplier dissolution. This state recognizes that customers see that some relationships have run their course and are no longer delivering satisfaction. If customers perceive this as an important question, then perhaps account management programmes should recognize its importance.

An issue not addressed by Millman and Wilson or McDonald et al. was: ‘When does the transition of responsibility take place between salesperson and account manager and how is that process managed?’ Elsewhere in this book the point is made that key account managers are primarily managers, not salespeople. This is an important issue. When is an account recognized as being key or strategic, and by whom? Millman and Wilson suggested that much of the early-stage work of investigation and assessment of key account attractiveness was carried out by salespeople, but can salespeople be expected to analyse the long-term potential of their accounts, and if they do identify such potential, will they be keen to share that knowledge when the result may be that the account passes (together with its commission) into the hands of others?

Valuable though this work was in developing our understanding of the various stages of relational development, the findings were largely descriptive, and although management implications could be drawn from these findings, little insight was provided to instruct practitioners in managing the process of key account development.

The Millman–Wilson article (1995) had posited a link between the PPF model and the relational development model that promised to provide insights into the management of key account relationships through the development stages. Later, McDonald et al. (1997) also explored the impact upon the KSAM process of two of the underlying concepts of the model, those of product and process, although they do make mention of ‘the ease of doing business’ which is similar to the term ‘making it easy to do business’, one of the descriptors used by Wilson (1993) when explaining the meaning of facilitation within the PPF model (Table 3).

The PPF model, as presented by Wilson (1993), posited that the nature of dyadic organizational relationships was directly related to the nature of problems that the parties focused upon resolving. It was proposed that there were three orders of problem, related to product (e.g. product performance, conformance to specification, price, etc.), process (how the product offering related to the manufacturing and value-creation processes of the customer) and facilitation (the way in which business was carried out by the two parties and the strategic impact of the relationship). These problem-related issues were seen as hierarchical in that the lowest level of problems related to product was associated with more distant relationships, while the more complex higher-order problems related to process and facilitation were associated with increasing organizational closeness. They were also perceived as cumulative in that it was impossible to address higher-order problems unless lower-order problems had been resolved.

Millman and Wilson (1995) present the findings of a series of research studies that give evidence to support the validity of the PPF model and its integration with the Millman–Wilson model in providing a framework for effective KAM. In doing so it also discusses some preliminary findings from a study into global KAM (Wilson et al. 2000).

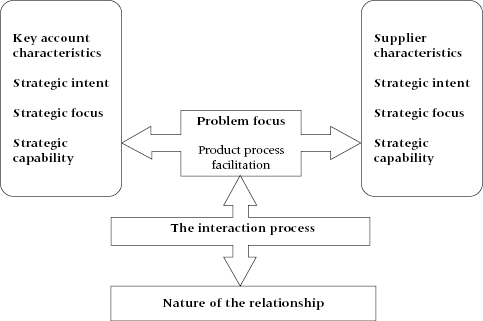

The development of the PPF model and its integration with the relational development model

The PPF model (Figure 2) draws primarily upon the IMP model of buyer–seller interaction (Campbell 1985; Ford 1990; Håkansson 1982), the fundamental difference being that the PPF model proposes that problem resolution lies at the centre of the interaction process. The figure suggests that five major variables impact upon the nature of the interaction process within the wider industry–cultural context in which the dyadic partners operate: the prevailing atmosphere of the relationship, the characteristics of both buyer and seller, the interaction strategies that they adopt, the order of problems they choose to focus upon and the specific nature of the problem that the buyer and seller are confronted with.

Figure 2 The PPF model

The attributes that relate to the first two sets of variables draw on the Campbell (1985) model of buyer–seller interaction, the Ford (1990) representation of the IMP model and Lamming's (1993) perceptions of industry–cultural change over time. The third set of variables is based upon the strategic options defined by Håkansson (1986), refined by the addition of a number of cultural characteristics which, it is proposed, predispose either buyer or seller towards closer or more market-based relationships. The variables that relate to the nature of the problem draw on the work of Brown and Brucker (1990) in extending the RFW framework (Robinson et al. 1967) to highlight the problem-centred nature of industrial purchasing. In addition, these problem-related variables draw on Håkansson's (1982) concepts of limitation and handling problems and upon the issues of need, market and transaction uncertainty identified by Håkansson et al. (1977).

Håkansson et al. (1977) suggest that inter-organizational relationships are characterized by attempts to reduce levels of uncertainty. Where high levels of uncertainty exist about buyer need (need uncertainty), there is a tendency for organizational interaction to increase in order to solve buyer need-related problems. Market uncertainty represents the dilemma faced by buyers when choosing one supplier over another: the very act of choosing will preclude their receiving the benefits represented by alternative sources of supply. Håkansson et al. (1977) suggested that levels of uncertainty were reduced through the application of the need-serving abilities and handling capabilities of the supplier.

Håkansson (1982) identified two groups of problems of concern to dyadic partners: limitation and handling problems that are closely related to the need-solving and transfer capabilities discussed by Håkansson et al. (1977). Limitation problems are identified as being concerned with resolving issues relating to technology, organizational structure and knowledge, and both determine which types of customers will be served, for example price or value seekers, and whether to differentiate between customers in terms of the level of service offered. It is suggested that the level of internal competence displayed by the seller in meeting customer need, or the demands made by the seller upon suppliers, effectively limit the range of suitable relationships. While not confined to being transaction specific, these elements are concerned with the relatively short-term issues of delivering product and service offerings, and with determining whether transformation and process capabilities may be applied to specific relationships.

Handling problems, however, are identified as being concerned with the long-term development of the relationship. They centre upon relative power and dependency and upon issues of conflict and cooperation. As such they may be viewed as occurring within the cultural and social context of the relationship reflecting the atmosphere in which business is done; the strategic orientation of each party, and the nature of the social interaction, experiences and personal relationships represented within the relationship. The importance of these observations to the development of the PPF model is two-fold:

The concept that problem resolution is at the heart of buyer–seller interaction is addressed by other writers. Using the analogy of a river, Brown and Brucker (1990) perceived the industrial buying process as a problem-solving stream of behaviour, with industrial buyers being differentiated by their function and location in relation to what they call the ‘channels’ and ‘bars’ that mark the flow of the decision-making process.

The value of this model is that it focuses the process of buyer–seller interaction upon problem resolution and recognizes that both buyer and seller are active within that process. It also suggests that there is a hierarchy of problems, with some requiring greater allocation of resources than others. It further suggests that the seller is able to influence the buyer's perception of the nature of the problem by focusing upon the differing needs of functional specialists throughout the problem-solving process, and thus provides a framework within which the seller may identify potentials for competitive advantage.

In bringing together the concepts of uncertainty (need, market and transaction), handling and limitation problems and the problem-solving stream of buyer behaviour, three central themes may be identified. Levels of uncertainty will influence the nature of relationships that develop between buyers and sellers. For example:

- High need uncertainty will tend to create closer relationships.

- High levels of market uncertainty will tend to create more switching between suppliers and less close dyadic relationships.

- Transaction uncertainty will be reduced by greater levels of cultural, linguistic and organizational congruence which in turn lead to greater closeness between trading partners.

Firms are faced with the problems of who to do business with and on what basis (limitation problems), and how to manage relationships as they evolve (handling problems). Problems which buyers and sellers focus jointly upon resolving are hierarchical in nature.

The PPF model identifies three orders of problem associated with managing ongoing relationships and classifies these as product, process and facilitation (see Table 2). These problem areas are hierarchical, in that problems related to product and base technology issues are of a relatively low order and are associated with shallow inter-organizational relationships. Process-related issues reflect an interest in systems and process capabilities which require closer relationships for their realization, while facilitation problems are concerned with strategic issues whose resolution requires high levels of integration and commonality of purpose.

Table 2: Nature of problem by category

| Problem category | Nature of problem |

|---|---|

| Product | Availability Performance Features Quality Design Technical support Order size Price Terms |

| Process | Speed of response Manufacturing process issues Application of process knowledge Changes to product Project management issues Decision-making process knowledge Special attention in relation to deliveries, design, quotes Cost reduction |

| Facilitation | Co-value creation Compatibility and integration of systems Alignment of objectives Integration of personnel Managing processes peripheral to customer core activity

|

These constructs have received considerable support from empirical observation and the resolution of different orders of problem closely related to the different stages of relational development posited by the Millman–Wilson model of relational development. There are also obvious links with the concept of the role of the political entrepreneur mentioned elsewhere in this book.

Selected findings from the work of Millman and Wilson support the overall validity of the PPF model and link orders of problem resolution to the various stages of relational development.

- Buyers and sellers in industrial and organizational markets interact within the context of problem resolution, and product or service acquisition is incidental, not central to that process.

- Industry culture acts as a constraint upon the types of relationships that develop between buyers and sellers in a given industry.

- Company characteristics influence the nature of inter-organizational relationships and, in particular, are related to management style and attitudes towards salespeople and customers.

- Three orders of problem were identified from the data, which refined the concepts of product, process and facilitation-related need.

- There was strong support for the contention that these three types of problem are hierarchical, that they are associated with different levels of relational closeness and with different negotiation concerns.

- While hierarchical, these problem foci are also cumulative in that it is not possible to focus only upon facilitation issues without resolving issues related to product and process.

Discussion

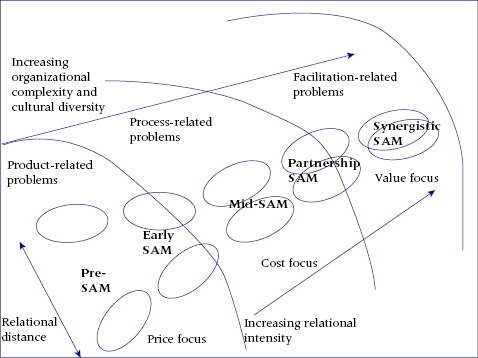

Relationships between buyers and sellers grow progressively closer as the problem focus moves from product through process to encompass facilitation issues. Their effect is cumulative in that higher levels of relational interaction are not associated with an exclusive focus upon process or facilitation but upon facilitation, process and product issues. The association between problem focus and relational development is represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3 The relational impact of focus on different forms of problem resolution

Millman and Wilson suggest that where sellers concentrate upon meeting only the product-related needs of their customers, the relationships they have tend to conform to pre- and early KAM relational forms. Relationships will be essentially arm's-length, transaction focused and display low levels of customer involvement. Only where suppliers have exclusive (monopoly) ownership of product technology can they hope to achieve sustainable competitive advantage solely through product-related problem resolution. Increasing product homogeneity in many markets suggests that this is not often the case and, in the absence of clear product differentiation, the tendency is to compete on the basis of price. Where price becomes the main focus for negotiation, relationships are likely to be increasingly transactional and arm's-length.

The development of process capabilities appears to be associated with the ability to manage the firm's supply chain, to forge alliances with other players in the marketplace and to enhance internal process capabilities. Suppliers that recognize the importance to customers of reducing cost within their value-creation process, and can convince their customers of the value of addressing those process-related issues, tend to develop closer relationships with their customers and are less often the victim of competitor activity. Problem-solving activity at this level is associated with buyer–seller relationships that have reached the mid-KAM stage and may be developing towards partnership KAM. Increasing organizational closeness is both a cause and an effect of focusing upon process-related issues. As the seller demonstrates their ability to solve problems of this order, so trust develops and inter-organizational contact networks grow, but access to personnel and information within the client organization is also a prerequisite for understanding process-related need. Neither does performance in this area reduce the importance of meeting the buyer's product need. High levels of product performance are a given at this stage.

It also became clear that the focus of negotiation is no longer price but the total system cost that the buyer will bear. The resolution of process-related problems that deliver substantial cost savings to the buyers allows sellers to charge premium prices for their base product offering, or to charge management fees for facilitating the process of employing commodity products in customer processes.

Facilitation issues are addressed at the mid, partnership and synergistic phases of the KSAM development process. Facilitation problems were found to be associated with the way business was done: it involves adaptation on both sides of the dyad, a drawing together, both in physical terms through modifications to internal systems processes and organizational structures, and in cultural and strategic terms. At this stage the seller is addressing the fundamental strategic needs of the buyer through a focus upon joint value creation (partnership), the creation of inter-organizational teams (virtual organizations), the performance of non-core management functions, and the joint development and exploitation of technologies and markets. Through addressing facilitation issues relationships become extremely close, the subject of negotiation moves from cost to value, and the danger from competition is slight because of the difficulty of replicating the benefits that are embedded in the relationship. Table 3 summarizes the link between KAM relational states and PPF strategies appropriate to them.

Table 3: KAM relational states and PPF strategies

| Development stage | Objectives | PPF strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-KAM | Identify/disqualify as potential key account Establish account potential Secure initial order | Identify key contacts Establish nature of product need Identify decision-making process Display willingness to make product adaptations Advocate key account status ‘in house’ |

| Early KAM | Account penetration Increase volume of business/share of wallet Become preferred supplier | If attractive, invest in building social relationships If unattractive, serve through low-cost channels, e.g. telephone or intermediaries Identify process-related problems and show willingness to provide cost-effective solutions Extend social network Build trust through performance and open communication |

| Mid-KAM | Build towards partnership Become first-tier or single-source supplier Establish key account status If limited potential for development then evolve a standard offering | Focus upon process-related problems Manage the implementation of process improvements Build teams between the two organizations Establish joint systems Perform management tasks for the customer |

| Partnership KAM | Develop spirit of partnership Lock in customer by providing external resource base | Integrate processes Extend joint problem-solving teams Focus upon cost reduction and value creation Address facilitation issues relating to culture, language, etc. |

| Synergistic KAM | Continuous improvement Shared rewards Quasi-integration | Focus upon joint value creation for the end user (customer's customer) Establish semi-autonomous project teams Establish cultural congruence |

More recent research

Evidently, some important elements of KSAM relational development were not addressed by the original model and much useful work has subsequently been done to flesh out the bones. One such body of work is that emanating from Cranfield and summarized in Woodburn and McDonald (2011). They identify 11 relationship features that vary with specific KAM relational states (see Table 4).

Table 4: Relationship features that vary with specific KAM relational states

| Relationship feature | Ranging from: | To: |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship emphasis | Research and reputation at pre-KAM | Open and strategically focused at synergistic KAM |

| Supplier status | One of several/many | Sole, possibly primary |

| Ease of exit | Easy, not started trading | High exit barriers, separation traumatic |

| Information sharing | Careful, as necessary | Open, even on sensitive subjects |

| Contact | Channelled through individual key account manager | Intimate: focus groups and teams |

| Access to customer | Customer request only | Constant both sides |

| Adaptation of organization and process | Standard | Joint processes, new organization |

| Relationship costs | May be small or large, speculative investment | Major running costs, larger sums but easier to identify |

| Level of trust | Exploring reputation and ‘signals’ | Trustworthiness assumed at all levels |

| Planning | Variable | Joint strategic long-term planning |

| Relationship potential | Important to qualify as key account | Very good/excellent in revenue and profits |

These conclusions strongly support the earlier findings of Millman and Wilson as presented below.

While providing more detail characterizing the various ways in which key dyadic relationships develop, it is still in relatively broad brushstrokes and it would be interesting to map each of the 11 elements in Table 4 to problem focus.

The work of Ryals and Humphries (2007) is also of interest and, in exploring the links between the perception of relationship development from both a supply chain and key account management perspective, opens a rich area of potential research that may provide further insights into how and why relationships between key suppliers and their customers develop over time. Again, it may well be fruitful to explore the issues of value creation and exchange, trust and reliability, flexibility and responsiveness, stability and communication from the perspective of problem resolution and from both the key account and supply chain management side.

Conclusions

The PPF model, when linked to the Millman–Wilson relational development model, becomes a powerful tool for key account managers. It provides a diagnostic tool for analysing the present stage that a particular relationship has reached, for analysing the potential for relational development that exists both in particular industries and within the context of specific dyads, and for managing that relationship over time.

Many companies have been observed using problem resolution to develop relationships with their customers, but few were observed to do this in a deliberate or structured way. The PPF model offers a conceptual framework within which this may take place. The development of capabilities in the areas of product, process and facilitation expands the range of relationships that a company can form, and a focus upon resolving different orders of problem allows those relationships to be developed.

Product-related capabilities are relationship-qualifying criteria. If a company cannot offer a product or service that meets consistently high-quality, performance and cost criteria, then it will not remain in the market for long.

Process capabilities offer the seller a first step towards achieving competitive advantage and customer loyalty. Process capabilities are normally perceived as those internal abilities that allow the firm to improve its market offering. The PPF model, in contrast, extends the concept of process capability to include the ability to help customers enhance their process capabilities.

In many industries this may require firms to adopt a fundamentally different approach to the market from their competitors. It requires that they facilitate the ease with which their customers can do business with them. It requires that suppliers provide their customers with a bespoke offering aimed at joint value creation, the alignment of objectives and often the sharing of managerial responsibility. Sellers must perceive themselves not as separate from their customers but as part of their total organization, intimately involved in providing value for their customers' customer. This is not to argue that all relationships should be treated alike, rather that each relationship should be judged on the basis of its potential for (co-)value creation through problem resolution and strategies adopted accordingly (see Table 3).

The PPF/relational states model further offers a conceptual framework within which new approaches to the development of competitive strategies may be forged, one that focuses upon managing relationships rather than products. Within industries that are short termist and which retain a strong focus upon transactions rather than relationships, this may well be difficult. However, as is the case with new products, so it may be with new ways of doing business, that the first to market gain enormous advantage over their competitors. The potential certainly exists within niche markets and among smaller, flexible companies to experiment with this form of account management, identifying and solving bespoke problems for their customers in order to help them compete better in their own markets.

Note

Revision of ‘A problem centred (PPF) model of buyer–seller interaction in business to business markets. Journal of Selling and Major Account Management (1999) 1(4).’