‘Vertical coopetition’: the key account perspective

Abstract

Why do key accounts combine opposing types of relationship with their suppliers? The author has chosen to term this new hybrid form of supplier relationship management, which combines cooperation and price-competitive transactions and reflects the tension between value creation and value appropriation, ‘vertical coopetition’. She investigates the use of this concept in the context of an in-depth qualitative study, involving, first, an exploratory field study and, second, four case studies involving leading industrial MNCs (multi-national companies). The results indicate that ‘vertical coopetition’ occurs in two forms: when the price-competitive approach is predominant but some cooperation features are still to be found; and when cooperation is predominant, but appeals to competition are still made. Mutually opposed aspects of each form are linked and explained by three pivotal mechanisms, which the author calls ‘strengthening’, ‘correction’ and ‘commuting’. Finally, the study reveals that, increasingly, the key account's brands or business unit value are explanatory forces of ‘vertical coopetition’.

Introduction

‘Coopetition’ is a term which arose in the 1980s to refer to inter-firm relationships that involve simultaneously both ‘cooperation’ and ‘competition’. The concept links two mutually exclusive types of relationship and merges them into a hybrid form. The concept has attracted an increasing amount of interest on the part of academia since the 1990s, marked especially by the seminal work of Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1995, p. 59) who used game theory to ‘encourage thinking about both cooperative and competitive ways to change the (strategic) game’. From a managerial perspective, companies that are competitors are increasingly cooperating to improve their competitive advantage over their other global competitors (we have numerous examples in the automotive industry, such as the recent discussions between BMW and Peugeot:1 ‘BMW is examining whether to share platforms with French rival PSA Peugeot Citroën for its Mini small car’). However, the ‘coopetition’ approach is often restricted to ‘horizontal’ relationships, e.g. among competitors (Bengtsson and Kock 1999, 2000) and there is little academic research applying the concept to ‘vertical’ relationships, e.g. between customers and suppliers.

Exploring the concept of ‘vertical’ coopetition

Heide and Wathne (2006, p. 98) ‘posit that exchange relationships may simultaneously involve different types of orientations … Although we endorse this view as it applies to individual transactions, our framework is based on the assumption that actual shifts among fundamentally different relationship orientations are both possible and likely.’ Most researchers find it conceptually easier to work on the polar aspects of the relationship continuum, rather than on the ‘hybrid’ forms combining these two aspects.

Consequently, many researchers have shown that a relational and cooperative orientation is key, in customer–seller relationships, to improving value creation and the customer's competitive advantage (Anderson and Narus 1991; Cardozo et al. 1992; Day 2000; Dunn and Thomas 1994; Dyer and Singh 1998; Ford 2001; Grönroos 1997; Jap 1999; Morgan and Hunt 1994) and is increasingly the norm in buyer–seller relationships (Walter et al. 2003). For these academics, value creation is optimized via cooperative relationships (Ulaga and Eggert 2006), even if they recognize that ‘customer firms perceive value creation as positive only if they appropriate a larger slice of the bigger value pie’ (Wagner et al. 2010, p. 1).

If we leave the subject of value creation to one side and turn our attention to the appropriation of value between customers and sellers, we find that some researchers have demonstrated that both parties could also ‘compete’ in terms of value sharing in a game theory setting (Zerbini and Castaldo 2007). Value sharing between customer and supplier can lead to competition between both parties as value appropriation is a zero sum game: the more one party appropriates value, the less will be left to the other. As we discussed above, customers will want the largest possible share: they will move value competition between them and their suppliers to competition among their suppliers. By forcing suppliers to compete among themselves, customers lead such suppliers to offer the largest possible value share to customers to win or keep the business from other suppliers. This is a way for customers to make sure they optimize value sharing in their best self-interest. This is how competition, and more specifically price competition, among suppliers reflects ‘value sharing’ competition between suppliers and customers. These two different ways of managing value are referred to as ‘pie expansion’ (Jap 1999) – the creation of value within a cooperative relationship – in contrast to ‘pie sharing’ (Jap 2001) – sharing value, competing to get the biggest slice. These two approaches complement each other while using opposite relational tools: cooperation and competition.

Within the relationship-marketing paradigm, we also find a conceptual approach that opposes two types of marketing: transactional and relational marketing are mutually exclusive at both ends of a continuum (Day 2000). On the one hand, we have the search for cooperation to gain mutual benefits (Dunn and Thomas 1994); on the other, an emphasis on short-term transactions with price-related benefits designed to attract new customers (price competitive transactions). There has as yet been little academic interest in the ‘grey area’ in which transactional and relational features are supposed to become intertwined in the middle of the continuum, or how ‘pie expansion’ and ‘pie sharing’ can overlap and merge. The paradox inherent in combining these two mutually exclusive forms of relationship has been recognized. Indeed, some researchers from the IMP Group,2 who study both the marketing and procurement perspectives, agree that buyer–supplier relationships encompass both cooperation and conflict (Håkansson and Snehota 1998), but the area in which transactional and relationship marketing co-exist remains unexplored.

Furthermore, the polarization of transactional and relational features is reflected in marketing literature, in which the supplier's viewpoint is emphasized; but how appropriate is it to prioritize the point of view of the supplier over that of the customer (Blois 1996)? What happens if it is in the interests of the customer to safeguard his or her independence of choice within the market rather than select a few dedicated suppliers, or if the customer prefers to combine both approaches? Is it not the customer who creates a paradoxical tension between capturing value from relational benefits provided by key suppliers (Ulaga 2003; Ulaga and Eggert 2006) and takes advantage, at the same time, of price-competitive market transactions (Gummesson 1997), and organizing tenders?

Exploring ‘vertical’ coopetition from the key account perspective

If we take a specific customer perspective – the key account perspective – we focus our analysis on those customers who ‘purchase a significant volume, buy centrally for a number of geographically dispersed organizational units and desire a long-term, cooperative working relationship as a means to innovation and financial success’ (Colletti and Tubridy 1987; Stevenson 1980). Their key account status is defined by their expectation that they will represent for their suppliers ‘a natural development of customer focus and relationship marketing in business-to-business markets’ (McDonald et al. 1997). Such customers therefore symbolize the ‘New frontier in relationship marketing’ (Yip and Madsen 1996). At the same time, they may set up their own e-market places (as Danone, Henkel and Nestlé did with the CPG Market), including electronic auction tools, and use transactional tools to manage their supplier relationships though price competition.

Electronic bidding tools, such as reverse auctions, have decreased the transactional cost of selecting from an enlarged supplier base. Jap (2003) shows that electronic auctions can reduce a negotiation process lasting six weeks to only a few hours, while Smart and Harrison (2003) use a case study to demonstrate that e-tender can generate a 30% price decrease. Electronic tools have sparked a renewed interest in the transactional approach that marketing researchers believed had been swept away by the relationship marketing paradigm (Day 2000; Grönroos 1994). Thus, key accounts do combine cooperation and competition in the form of price-competitive transactions, paving the way for ‘vertical coopetition’ as a new and hybrid form of supplier relationship management.

Research objective

From a conceptual viewpoint, we need to understand why key accounts create this ‘hybrid’ form of relationship with suppliers. As yet, no one has examined the reasons why customers ‘coopete’ with suppliers.

In this paper ‘vertical coopetition’ is thus analysed from the sole perspective of key accounts acting in their own self-interest and disregarding the optimization of mutual welfare. Our analysis is grounded in managerial practice, we study ‘vertical coopetition’ as a tool designed to optimize value creation and appropriation for key customers, whose status is characterized by an asymmetrical position imbuing them with a certain amount of power.3 We explore a specific relationship background and do not study the conditions of a Walresian buyer–seller network equilibrium (Corominas-Bosch 2004; Kranton and Minehart 2001). Although the literature on networks in buyer–seller relationships includes a study of two polar features encompassing non-cooperative behaviours and some link (relationship) patterns, the quest for economic balance depends on prices. Our study, meanwhile, analyses value as a ‘coopetitive’ relational driver.

Our research challenges the prevalent view of normative, collaborative buyer–supplier relationships and it attempts to provide a more nuanced theory. From the literature on relationship marketing, we analyse the benefits of relational and transactional exchanges with a view to gaining an insight into why key accounts prefer to combine aspects of both approaches. We then examine the concepts, most of them originating in the field of strategy, that explain ‘horizontal coopetition’ (Bengtsson and Kock 1999, 2000; Garrette and Dussauge 1995) and check whether and how they can be applied to ‘vertical coopetition’.

From a managerial perspective, a greater understanding of the drivers used by key accounts in setting up hybrid forms of relationship is required to help organizations analyse emerging purchaser roles more effectively. Our goal is to study how the concept of ‘vertical coopetition’ can be applied to key accounts and to dissect the whole mechanism of combining polar forms of relationships.

The paper is structured as follows. First, positioning the research within the academic literature on hybrid forms of relationships, combining opposing concepts. Second, describing the research methodology. To reach our goal, we conducted a qualitative research programme including an exploratory survey involving ten in-depth interviews of senior purchasing managers from ten different manufacturing or service MNCs, refined by four case studies, taking a more balanced view of purchasers and ‘internal’ customers (users or influencers) within the key customer organization. We also checked data with respondents collected from their supplier companies (key account directors). Our analysis and interpretation of the results led us to define two major types of ‘vertical coopetition’: a cooperation predominant form of coopetition and a price-competition predominant form of coopetition, each of them including three different types of ‘pivots’ linking cooperation and price-competition approaches: ‘strengthening’, ‘correction’ and ‘commuting’. Finally, we discuss the factors explaining the use of vertical coopetition. We conclude with the managerial implications of our findings and provide directions for further research.

Relational versus transactional benefits

To understand why key accounts should consider combining cooperative and price-competitive relationships, we will first examine what benefits they can derive from each type of relationship. We will define those benefits based on an analysis of definitions derived from previous scholarly work on polar relationships (Dwyer et al. 1987; Grönroos 1994; Macneil 1978, 1980; Payne et al. 1995).

Mostly non-economic in nature, relational benefits are derived from cooperation and based on value creation and sharing (Anderson and Narus 2004, 1999). Value creation based on long-term cooperation can be broken down into product-linked benefits (quality, innovation, etc.), service-linked benefits (supply chain optimization, supplier's specific know-how, etc.) and interaction benefits, such as problem-solving (Ulaga 2003). Some direct economic benefits may also be added, such as cost-reduction programmes and bonuses, but they are generally the outcome of the relational benefits alluded to above. These benefits can be generated only if both key account and supplier achieve a high level of interaction and mutual knowledge which enable them to work continuously on the principle aspects of the value chain (Porter 1980, 2008).

As well as cooperation and relational benefits, competitive market price exchanges generate transactional benefits. Competitive market price exchange enables key accounts to achieve the best price/quality ratio in their offer. Being a short-term transaction approach, it provides customers with a good overview of the market and, therefore, furnishes them with the opportunity to change suppliers whenever they want, a useful capability in terms of exploiting market innovations. This type of exchange enables key accounts to remain relatively independent from their suppliers and to act according to their best self-interest.

Understandably, key accounts want to combine both types of benefit simultaneously exploiting relational benefits and achieving the best price (for a specific offer). However, the problem here is that the two types of relationship are paradoxical. This implies a choice between either a long-term relationship with pre-selected suppliers and joint efforts to create value from non-economic benefits, or a transaction-by-transaction approach designed to benefit from the best specific offers. We will now investigate how key accounts can overcome this paradox by means of ‘vertical coopetition’.

From horizontal to vertical coopetition

Aliouat (1996), whose research is based on the seminal work of Axelrod (1980; Axelrod and Hamilton 1981), suggests one major explanation for the paradoxical use of the two approaches within a ‘horizontal’ context that can be applied to ‘vertical’ relationships. There may be a paradox associated with a situation characterized by interdependence: key accounts may combine cooperative and aggressive behaviours to maximize their earnings. This can be illustrated by means of game theory.

If we refer to Aliouat's cooperation benefit matrix (1996, p. 74), cooperation can generate mutual earnings of 100 to both the key account and the supplier. But if aggressive behaviour is added by the key account to the cooperation, for example, the launching of a competitive bid, those earnings can reach 200 and be doubled for the key account. Such an approach will bear fruit until such a time as the supplier becomes wary and starts to mistrust the key account, at which point it will inevitably begin to incur losses. Thus, it is in the key account's interest to find a trade-off between cooperation and calling for competitive bids to optimize earnings.

As early as 1989, Braddach and Eccles had rejected the transaction cost economic continuum with two mutually exclusive poles going from market to hierarchy. They ‘emphasize how transactions controlled by one mechanism are profoundly affected by the simultaneous use of an alternative control mechanism’. Here, they hint at an unbalanced interaction between two mechanisms, in which a less powerful one influences its more powerful counterpart. Developing this line of reasoning, we can surmise that one type of relationship is used to soften the impact and ‘correct’ the other one. An example would be the use of market price competitive exchange to ‘correct’ inherent problems in the cooperative approach, i.e. the risk of opportunism on the supplier side.

The notion of correction suggests that coopetition does not necessarily imply a perfect equilibrium between cooperation and price competition: one form of relationship may be predominant, with the other appearing as secondary, mitigating the effects of the first one.

In the field of strategy, Bengtsson and Kock (1999, 2000) have produced in-depth studies of coopetition within horizontal alliances in B2B networks, analysing how firms combine the advantages of competition and cooperation. The authors define three forms of coopetition: when cooperation dominates, when competition dominates and when cooperation and competition play equal roles.

The choice of each form is defined by the specific resources available to individual competitors. This approach can be applied to ‘vertical coopetition’ to produce a description of the same three forms of coopetition. The more the suppliers have strategic resources required by the key account, the more cooperation is predominant. The scarcer those resources are and the more fragmented they are among a large number of suppliers, the higher the level of price competition.

To complement the insights from the literature review, which reveals three forms of coopetition, we will now turn to an initial empirical study both to justify and to refine our theoretical framework.

Development of theoretical framework

The empirical stage of our research involves firstly a field study; the objective of which is to define whether the findings of our review of the literature on horizontal relationships can be applied to vertical relationships.

Field study

We decided to select ten MNCs that are the leaders in their respective industries and would have key account status with their suppliers. We purposely selected MNCs from both the industrial and service sectors with a view to maximizing the sample's diversity and uncover a wide variety of supply relationships within the business-to-business sector.

We conducted ten in-depth interviews with purchasing managers and directors with substantial experience in the field of purchasing. The interviewees were contacted through the alumni network of a business school. On average, the interviews lasted between an hour and 90 minutes. We applied a semi-guided interview technique developed by a French researcher (Romelaer 2005, p. 114). All the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed by the author within 72 hours. We used thematic coding and mapped relationships conceptually (Miles and Huberman 1994, 2003).

Refined theoretical framework

This initial field study confirmed that out of the ten companies interviewed, nine had hybrid forms of relationship with their suppliers. The exception to this rule was provided by a company dealing with purely relational features in an industry in which prices are fixed by law.

The field study revealed that two hybrid forms of vertical relationship are predominant:

This is consistent with Bengtsson and Kock (1999, 2000), except that in vertical relationships, at least among the companies studied, no balanced form of relationship between competitive pricing and cooperation was to be found: there was always one predominant form mixed with a secondary, weaker one.

We also found some interesting mechanisms linking the two forms of relationship. As hinted at by Braddach and Eccles (1989), one form of relationship would ‘correct’ the weaknesses of the other, but could also ‘strengthen’ the qualities of the other form. In certain circumstances, one form would also ‘substitute’ another.

Case studies

To complement the insights from the field study, we carried out four comprehensive case studies (Yin 2003) as we needed to understand in detail how the mechanisms and the dimensions described here work.

We chose to study four global MNCs, leaders in their industry in three different sectors: industrial equipment (Case 1), packaging (Case 2) and FMCG (Cases 3 and 4). To keep things even, we decided to focus on four manufacturing MNCs. When there was a need to focus on a specific supplier or product, this choice was determined by the Anderson and Narus study (1991), which points out that corrugated cases were on the transactional (price-competition) side of the relational continuum whereas industrial equipment was on the cooperative side. By selecting ‘polar’ products, we were able to gain an insight into the influence of specific products on the choice of relationship. Since it was of critical importance to question influential decision-makers involved in selecting and monitoring supplier relationships, we conducted in-depth interviews with senior executives.

We selected global and European purchase managers/directors (six informants) and ‘users’ (four informants, including a project director, a corporate technical manager and a sensory panel manager). In the interests of external validity (Yin 2003) and to avoid a strictly dyadic approach, we also interviewed suppliers (key account managers and directors – five informants) working with a number of the MNCs in the sample. We also selected ‘expert’ CEOs who were heading up different organizations, one of them stressing marketing and KAM roles, the other a procurement role. To ensure that the data derived from the interviews were valid, we organized a number of presentations with key informants during which we asked them to assess our conclusions. During these presentations we had the opportunity to clarify some minor findings. Our final sample consisted of around 25 informants (including informants from the field study). For the case studies, we applied the same interview and analysis technique as for the field study. We also used thematic coding (Miles and Huberman 2003, 1994). The original coding schemes from the field study were modified and refined as analysis progressed in the case studies and new concepts were uncovered.

Key findings

Key Finding No. 1: The pivotal points associating a relationship primarily based on competitive pricing with a number of relational features and the impact on value management.

Some key account buyers prefer to remain in an ‘adversarial’ type of relationship and put a lot of pressure on their suppliers with recurrent (sometimes unexpected) tenders to ensure the best price/offer from the market.

Expert: “What we have found is that when you purchase, in a sense, you often get the best terms when there is a degree of uncertainty and you get less good terms when you become obvious in the way you operate.”

Case 1: European Purchase Director: “I purposely do not develop long-term, committed and stable relationships.”

Although the type of relationship alluded to above is primarily based on the short-term transactions with price as a mediator, rather than the relationship itself (Dwyer et al. 1987; Grönroos 1994), it does include some relational features which ‘correct’ the strictly price-competitive approach. This is not merely due to the fact that transactions may be sustained (Dyer et al. 1998; Palmer 2007), but also due to the fact that key accounts want to compensate for the disadvantages of a lack of cooperation, especially in cases in which there is a commercial dispute to settle. Even if there is no commitment on the part of the key account, an element of trust will ‘correct’ the pure price focus and introduce some relational benefits, mostly in terms of information-sharing (Ulaga 2003).

Although self-interest is dominant, key accounts will not let supplier trust decrease below a certain threshold and thus will not focus exclusively on a transaction-based relationship in order to optimize their profits:

Case 1: European Purchase Director: “In all cases, key account status is going to help you, specifically if you have a commercial dispute … If the problem is enormous, you need somebody (the supplier) who can solve the dispute in a global way.”

If one relational benefit has to be sustained, within a predominantly transactional relationship, it is information-sharing focused on problem solving, especially if the problem arises from the key account's end customer.

In such situations, value is primarily derived from competitive prices (pie sharing) but one relational element may ease the pressure on the supplier during negotiations: a proven ability to settle problems rapidly, especially when such problems impact the end-user. This is in line with Abratt and Kelly's study (2002, p. 473) showing that the ability of ‘managers to identify problems and provide solutions within their key accounts is ranked as the number one success factor in key customers’ perception of customer–supplier partnerships.

Some relational features may also ‘re-enforce’ the price-competitive exchange: Sheth and Parvatiyar (1995, p. 399) recall the major axiom of this price-competitive approach (‘transactional marketing’): ‘One axiom of transactional marketing is the belief that competition and self-interest are the drivers of value creation. Through competition, buyers can be offered a choice.’

To get the best choice in a ‘bounded rationality’ situation (Simon 1959) a key account will maintain a certain rapport with a panel of suppliers in order to ‘optimize’ its market information gathering capabilities and obtain the elements enabling it to launch competitive bids at the appropriate time (fixing prices for a certain period of time when the market starts to rise, for example) and to work with the most appropriate players.

Case 1: European Purchase Director: “The important thing is to understand your supplier's sales strategy. So it's better to keep in touch with suppliers because it increases your negotiating capabilities. This is the reason why I never kick out a supplier: I just lower the volumes I grant them. Otherwise, you lose market knowledge and there is a loss of effectiveness.”

Here, and as paradoxical as it may seem, the relational benefit derived from information-sharing is used to reinforce the transactional approach and the appropriation of value on the part of key accounts: the focus is on ‘pie sharing’ and on obtaining not only the lowest prices but also the lowest sustainable prices. The primary tactic used to achieve this is tendering before market prices pick up and negotiating the length of contracts to prevent suppliers from recovering the full extent of price increases. Fine-tuning transactional strategies requires a great deal of market information and a degree of cooperation on the part of suppliers in terms of providing such information (certain suppliers may deem it in their interest to conduct some of their business at low profit levels in view of economies of scale).

Last but not least, once key accounts believe that the limits of the transactional approach have been reached, they often introduce a number of relational elements. Key accounts ‘commute’ from a predominantly transactional relationship to a more collaborative approach. Pillai and Sharma (2003) have studied how a mature buyer–seller relationship can follow a reversed U curve, migrating from a relational orientation towards a transactional one. This process can follow the opposite course with a relational orientation replacing a transactional one (Webster 1992). When buyers believe they have exhausted the possibilities of a transactional approach (achieving and maintaining the lowest prices on the market), they may choose to focus on relational benefits, such as improved quality, innovation, etc. (Ulaga 2003).

Study 7: Purchase Support Manager: “We can't pressurize suppliers on a long-term basis: if we do, we run the risk that a supplier may end the contract or cut corners on quality or on supply chain efficiency. In the end, we may suffer as a result or our end-customers may suffer.

We have more than met our cost-saving targets. So, we proved that we achieve cost-savings. We have worked with our suppliers on a variety of products, but we can't go below the lowest price. We can lower the price once, or twice, but we reach a limit when this is no longer possible … What we then try to do is to keep on working on price fairness, but we do this alongside product improvement, processes improvement, product differentiation and services. Today, we are in an innovation workshop.”

In such instances, value management is definitely sequential. The first task is to obtain the biggest share of the pie, after which the aim is to add non-economic benefits to that share.

Whatever the type of pivot used to introduce a relational orientation to a price-competitive relationship, it is always deployed as a kind of ‘incentive’ to obtain the most competitive market price while simultaneously keeping the supplier relatively happy. Key accounts will ‘soften’ the relationship, introducing relational benefits as incentives for the supplier. Those ‘incentives’ can take the form of information transfer (in the case of joint problem solving), which can help suppliers gain customer share, integration into the key account's long-term strategy, which can help suppliers to increase profits by reducing costs (Kalwani and Narayandas 1995), and increased value sharing (quality or innovation improvements), which can help suppliers to sustain wallet share.

Key Finding No. 2: The pivotal point associating a relationship primarily based on cooperation with a number of price-competitive features and the impact on value management.

Although this type of relationship is primarily collaborative and based on a quest for mutual relational benefits within a long-term relationship, rather than on short-term transactions designed to achieve the best market price (Dwyer et al. 1987; Grönroos 1994), some transactional features (Ivens and Pardo 2005) ‘correct’ the relational approach. The major reason is key accounts' fight against suppliers' opportunistic behaviour (Wathne and Heide 2000). Buyers want to be sure that, even when they have a long-term contractual commitment with a supplier, they will still get the most competitive price throughout the length of the contract.

Case 3: Global Purchase Director – Packaging: “If I have a price-competitiveness guarantee, I can commit to a supplier for a very long time. The price, as well as the margin, must be competitive in the appropriate market. I buy the largest volumes possible; I wouldn't be properly representing the interests of my company if prices were blocked at an initial level. If a gap between the supplier and market prices gradually develops, the supplier must return to the market level, even if this involves reducing his margins. If the supplier is unable to do this, then we have a major concern. I check the market price level all the time. Everybody wants to work with us.”

Case 4: European Purchasing Group Manager: “We have ‘framework agreements’ and we have an indexation clause on raw materials. (Nevertheless) we never accept a supplier's price without checking it with another supplier. In our contracts, it is stated that we can give any new project to any supplier. We have an obligation to discuss the matter with the (‘preferred’) supplier and he has a priority in terms of new business, but if his price is not good enough, we can give the new project to another supplier. Otherwise, it would be too easy! We systematically put out calls for tender for all new products.”

Although value is derived from creativity and a will to ‘increase the pie’, rather than just optimize their slice, key accounts do not want to suffer at the hands of suppliers increasing their own slice, and will make sure that, in relative terms, the slice they get is the largest proportionately to the increase in the value of the pie achieved in conjunction with the supplier.

Another reason why transactional features have the effect of ‘correcting’ the relational approach (a reason which has not been discussed in the academic literature, and a driving force in our sample), is that the competitive price approach is a way for key accounts' buyers to assert their role and credibility within their own companies. While they find it difficult to turn certain relational benefits into economic data, they can more easily use tenders to help them demonstrate any cost reductions they have made.

Expert: “So, it sounds peculiar, but in many large companies, purchasing departments are happy enough to see prices from their incumbent suppliers kind of moving up because they may have an opportunity to bring them down when it comes to the point when everybody is really watching their performance; this opportunity is the tender process.”

Calls for competition are also the symbol of the buyers' power, whereas some relational benefits (product development, quality improvement) fall within the remit of other key account departments (R and D or production).

It is at this point that ‘vertical’ coopetition is closest to ‘horizontal’ coopetition. As Bengtsson and Kock (2000, p. 419) observed, ‘Individuals in the material development departments at both companies cooperated with each other, while individuals in the marketing and product development departments competed with each other. Goals were jointly stipulated in their cooperation, but not, of course, in their competition.’ We find the same type of synchronic approach (Perret and Josserand 2003) when the coopetitive process is ‘compartmentalized’: the buyer takes care of the transactional orientation, whereas other actors or departments, which use the purchased product, will take care of the relational approach.

Study 3: Director, Global procurement EMEA: “(With users) you have this relationship (with the supplier) that may be very strong and erase all rational and unbiased decision-making. The role of the purchasing director is to bring some in-depth thinking to the relationship and provide opportunities; finding out whether we can find something better or cheaper on the market.”

Value creation is often difficult to turn into numbers, in the sense of well-defined economic benefits (how much is information-sharing worth?). Such cooperative strategies may appear to be subjective, and buyers often prefer the ‘objectivity’ associated with calls for tender (based on objective figures which can be used to calculate margins).

Case 3: Global Purchase Director – Packaging: “In the end, the power of the buyer resides in the fact that he can launch calls for tender … Savings exist because purchasers can demonstrate them; otherwise they are invisible.”

Coopetitive approaches of this kind reveal a desire to clarify value calculations: when the limits of the value pie are blurred, key customers go back to basics, calculating the size of their slice if they are not sure they can optimize it. Although it may seem paradoxical, some ‘price competitive’ features help to ‘re-enforce’ the predominant relational approach. Key accounts want to be reassured that suppliers are not behaving opportunistically. Calls for tender may be launched, but only for a few products or as a ‘benchmark’, leaving the supplier with most of its existing business with the key account. The supplier or a consulting company may be requested to benchmark a strategic product against a similar product in the market. Whatever the outcome, the supplier will not be at risk of losing the business but may be asked by the key account to re-align prices to reflect the market. The aim of the key account is to strengthen the relationship while ensuring that the supplier does not view it as a ‘captive’ customer. The price control mechanism is primarily used to reinforce suppliers' level of trust.

Case 3: Global Purchase Director – Packaging: “When we reach that point (with the supplier), we start to abandon the purely transactional approach. We talk more about projects and less about prices. We check whether the price is competitive, but we trust those people, since we know the gap between them and the other suppliers. We do not fool around challenging them every two months. When we (at the CEO level) talk about new technology, they answer: ‘Where you want to go, we will go.’ There is a strong trust relationship and they are able to react appropriately, whatever the situation. I see a future with them.”

In such a coopetitive strategy, value is almost exclusively derived from creation based on relational benefits (rather than directly economic ones). Interestingly, however, since the level of trust is very high, suppliers must ‘prove’ (by providing evidence) that they offer the largest value slice to the customer. This reinforces the willingness to work together to expand the size of the pie. The relationship thus becomes self-reinforcing.

Key accounts may also ‘commute’ from a predominantly relational approach to a formalized transactional one. Some key accounts will deploy a relational approach through the duration of a particular contract and then systematically renew it by means of a call for tender. They may also launch a competitive bid when the supplier's turnover with a specific product has reached a fixed limit. In such circumstances, the supplier's turnover may be at risk, but if it wins the tender, the relational approach will move forward.

Case 4: European Purchasing Group Manager: “We launch tenders, for instance, when we renew contracts. We do this with standard suppliers every year, with ‘key’ suppliers every two or three years, and with ‘strategic’ partners every five years.”

This last coopetitive approach demonstrates that an optimum level of trust can never be attained and that key accounts are keen to check on a regular basis that the non-relational benefits they derive are not detrimental to their goal of obtaining the largest possible slice of the pie. They also want to ensure that they will be able to modify the relational orientation if they fail to obtain the kind of slice they feel they are entitled to.

Again, whatever the mechanism used to add transactional content to a collaborative relationship, it will always be a form of ‘control’: calls for tender are used by the key account to ‘control’ their relationship with the supplier. Mirroring this inter-firm control mechanism is an intra-firm control mechanism in which key buyers apply a transactional approach to suppliers to control their own internal environment.

Key accounts have developed new ‘hybrid’ forms of vertical exchange with their suppliers, combining calls for tender with cooperation, applying either ‘incentive’ mechanisms to upgrade their supplier's level of commitment or inter-firm ‘control mechanisms’ to counter their opportunistic behaviour or, paradoxically, to maintain a high level of trust.

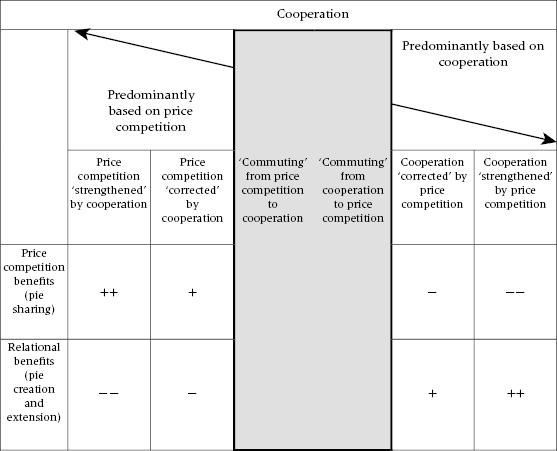

‘Correcting’ and ‘strengthening’ pivotal points alter the respective influence of predominant and secondary approaches. The ‘strengthening’ pivot emphasizes the predominant form, while the ‘correcting’ pivot emphasizes the secondary form. This leads me to define a vertical ‘coopetition’ continuum starting from price competition to a strong form of cooperation, as described in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The ‘coopetition’ continuum

Figure 1 represents a continuum along which the strengthening mechanism is located towards the polar end of the continuum. The ‘correcting’ mechanism, on the other hand, includes a number of advantages deriving from the second form and this mitigation places it half way between the middle and the end of the continuum. The ‘commuting’ pivotal point switches from one form of coopetition to the other and is located right in the middle of the continuum. These three mechanisms bring a degree of dynamism along the relationship continuum.

We have to understand why key accounts choose either a cooperation-predominant form of coopetition or a price-competitive one, and gain an insight into each of the two sub-dimensions of each predominant form.

Key Finding No. 3: The purchased product as an explanatory factor of the form taken by coopetition.

In the academic literature on purchasing and marketing, there is a direct link between product segmentation and the choice of relationship to be applied (Anderson and Narus 1991; Bensaou 1999; Kaufman et al. 2000; Kraljic 1983). In other words, the more the product is considered a commodity and the simpler the purchase process is, the more the focus will be on price; while the more the product or purchase process is complex, the more the focus will be on the relationship. My studies confirm these findings:

Case 1: European Purchase Director: “I checked that those processes (competition based on price) would work effectively when raw material makes a significant contribution to the final price of the product.

We don't have much room for manoeuvre: Coca-Cola varnish is Coca-Cola varnish. The day you want to change it, it's very difficult, extremely difficult. So you end up signing long-term agreements with people (suppliers).”

Nevertheless, the approach is still characterized by ‘coopetition’-based relationships: price competition is blended with a degree of cooperation, and cooperation is blended with calls for competition.

Case 4: European Purchasing Group Manager: “We don't go in for single sourcing. We never develop a single supplier (for one product range).”

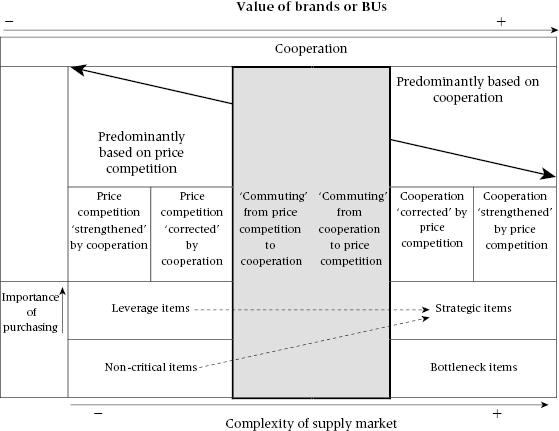

In reference to Kraljic's (1983) seminal work, non-critical and leverage products can be associated with price competition as the predominant form of coopetition, while bottleneck and strategic products can be associated with cooperation as the dominant form. Furthermore, it transpired from this study that it is not only in terms of product segmentation that the choice between predominantly cooperative and predominantly price-competitive coopetition can be analysed. A new moderating variable appeared in the value of the key account brand or BU (business unit) in which the purchased product is incorporated. Key accounts choose their different relational orientation with their suppliers in reference to the value these specific brands or BUs bring to their global business.

Key Finding No. 4: The key account's brand or BU value as a major explanation of the coopetition form.

The case studies mentioned above (specifically Cases 3 and 4) reveal a trend towards a greater sophistication in purchaser analysis. Buyers have moved from purchased product analysis towards a value analysis of their own brands and product ranges. As for products in Kraljic's matrix, brands or BUs are positioned on a continuum defined by the relative competitive advantage they provide in comparison with the other key account brands or BUs.

If the comparative competitive advantage is high and the brand or BU generates a high level of value for the key account, supplier relationships will be predominantly cooperative. According to Porter's classification, the purchase strategy will be based to a larger degree on differentiation mode and relational benefits will be sought. If the comparative competitive advantage is low and the brand or BU generates a low level of value for the key account, the supplier relationship will be predominantly based on price competition. According to Porter's classification, the purchase strategy will be based to a larger degree on a cost domination mode and the lowest purchase prices will be sought.

Within the same key account, a supplier of the same (purchased) product may be confronted with different relational orientations according to the brand or BU it is selling to. Buyers are, nowadays, increasingly involved in the process of creating value by means of brands or BUs and will therefore define their relationships with suppliers, not only in relation with the purchased product segmentation, but also according to their own brand or BU value segmentation.

Case 4: European Purchasing Group Manager: “In my team, people are organized in business units, which means that a European buyer will be responsible for a specific ‘spend category’, like solid board, but he or she will be responsible for one or two businesses (lines of final products). A pan-European supplier may work with different businesses, but he will not deal with the same buyer.

Obviously, the specific marketing strategy of each business will directly influence the type of relationships we want to have with the suppliers. In highly competitive markets, we may only apply a cost approach, on other high-range products [In this context, products are to be understood as products to be sold to the end user by the key account.], we will go for partnerships. The purchase strategy doesn't just involve looking for the best suppliers, it also implies matching the needs of our marketing people. Some businesses don't have the same needs as the others. From there, we will develop relationships (with suppliers) that we will differ according to our product lines.”

Case 3: VP Procurement: “(Buyers) are interested in brand profit, thus they are as interested in increasing brand profit and decreasing the cost of the product as they are in boosting the top line, the sales value of the brand.”

Case 3: Global Purchase Director – Packaging: “The future of our company is that buyers will be less and less connected to markets, but more and more connected to our brands. Some buyers will join marketing teams. These are senior buyers, who have experience in several markets. Their mission will be to improve the brand and work to develop it.”

In conclusion, we have two moderating variables that influence the choice of the dominant form (either cooperative or price-competitive) of coopetitive relationships; on the one hand, purchased product segmentation, and on the other, the value classification applied to sold product (brand or BU).

These two variables are not of equal weight: the sold product (brand or BU) classification takes precedence over product segmentation in determining the relational orientation to be applied. For instance, in terms of a purely purchased product segmentation, corrugated cases will be considered as non-critical or leverage products for which a coopetitive relationship, predominantly based on price competition, will be applied. But if the corrugated cases are used by the key account as RRP (retail ready packaging) for a high-value brand, then a coopetitive relationship, predominantly based on cooperation, will be developed with suppliers.

The Kraljic (1983) purchasing portfolio model is based on two aspects (Dubois and Pedersen 2002): the importance of purchasing and the complexity of the supply market. Our model adds a third aspect: the value of the sold brand or BU line of products. This means that a non-critical or leverage product may become a strategic product and that, in consequence, the ‘coopetitive’ orientation may transform from a predominantly competitive one to a predominantly cooperative one, as described in Figure 2.

Figure 2 The ‘vertical coopetition’ synthesis

‘Vertical coopetition’ has become a key concept in understanding the sophisticated and dynamic approach taken by key accounts to their relationships with suppliers. As we have demonstrated, the relationship is characterized by a combination of cooperation and price competition, but the respective roles of the two approaches within that combination may be influenced by two major variables: the purchased product itself and, more importantly, the value of the brand or BU in which the purchased product is incorporated.

Discussion and managerial implications

According to our research, this is the first time that an attempt has been made to conceptualize, using an approach grounded in managerial practice, the notion of ‘vertical coopetition’. Thus, my research contributes to a better understanding of the relational strategies applied by key accounts, outlining as it does a number of new trends in purchasing strategies.

Contribution from the key account's viewpoint

The first major change is a more pronounced internal trend away from purchasing and towards marketing. This means that major companies now place a greater emphasis on mitigating potential conflicts between purchasing and marketing and setting up working procedures that involve purchasers in the marketing decision process. Purchase managers may come to play an integral role in defining marketing strategy. They are increasingly expected to contribute at an early stage to key accounts' value creation processes. As such, they play an important role in selecting suppliers who ‘fit’ key account marketing needs as effectively as possible, while at the same time playing a more traditional role by ensuring that their companies achieve the best value share possible (the biggest slice of the pie). This may create a certain degree of conflict, in that purchasers are expected to find suppliers with whom they can optimize relational benefits while still maintaining a degree of price competition, which implies a relationship characterized by proximity tempered by a certain degree of distance (to safeguard independence of choice). In order to resolve conflicts over roles, purchasing organizations are using different tools. A new type of structure is emerging in which cooperation and calls for tender are managed by different people. Senior buyers take care of cooperation, which is often considered the ‘strategic’ part of the relationship, while junior buyers follow a defined process to organize tenders and supplier benchmarking mechanisms.

When this ‘split’ between different people within an organization is not possible, framework contracts (Mouzas and Ford 2006) are sometimes used to avoid role conflict. By defining, in an umbrella contract, both the relationship and long-term expectations, on one hand, and detailed rules for price competition (Request for Quotation) on the other, buyers become less schizophrenic since they are aware in detail of how coopetition strategies will be applied. Thus, buyers can maintain a certain distance simply by applying defined rules (even if they are the ones who have defined those rules).

These emerging trends may be food for thought for other customers, not necessarily key accounts, who wish to optimize their relationships with their suppliers.Contribution from the supplier's viewpoint

The implications of our research are also extremely important for suppliers. Suppliers can use this input to construct their own marketing strategy and, more especially, their key account programmes. Our research emphasizes the fact that suppliers must primarily focus on the brands or lines of products which their key customers believe deliver high value to them. This may provide a new vision of key account management in which key customers are no longer considered as a whole but in which specific segments of key customers are targeted – the fact that purchasers' responsibilities are defined along individual business terms may help to define this segment-based strategy within key accounts' range of brands. Furthermore, suppliers may also adopt a number of very different strategies with the same key customer: they may decide to go for price competition and standard products if they have a predominantly price-competitive relationship with their key accounts, or they may choose to position themselves at the other end of the relational continuum and work on relational benefits. The new perspective that our research offers can help suppliers to define a relational strategy based not on individual customers, but on their customers' brands and product lines. Following that line of reasoning, it is possible to imagine that key account management could become key (customer) brand management. Insofar as purchasing managers ‘merging’ into the marketing team is concerned, suppliers will have to focus on the competitive advantages they can bring to their key accounts, considered not in terms of their identity as single companies but in terms of specific brands and product lines.

Because of the key account ‘coopetitive’ approach, suppliers who want to work on a cooperative basis will always have to face pressure from key customers to lower their prices. Views on the nature of ‘cooperation’ have increasingly veered away from Jap's (1999) definition of ‘(creating) mutually beneficial outcomes for all participants’. Today there is greater pressure from key accounts to obtain a larger share of the ‘pie’ and ‘mutual’ is far from meaning ‘equal’. Suppliers have to think of relational benefits for their key customers not only in terms of delivering competitive advantages, but also in terms of doing so at a lower cost than other suppliers. This should encourage them to attempt to find synergies (to share development costs) and create relational benefits that can be offered to different, non-competitive key accounts. In order to do so, they will have to ‘decompartmentalize’ their key account management structure.

Thus the major conclusion of our research (within the limit of its exploratory nature) is that the concept of key account management may, in years to come, undergo major changes, as suppliers will need to develop transversal management approaches to their portfolio of key accounts in order to take advantage of the latter's most valued brands and share the development costs of relational benefits among different accounts if they want to guarantee success.

Conclusion and directions for future research

In this paper we attempt to bridge the gap between transactional and relational purchasing (derived from the relationship marketing paradigm) by defining the concept of ‘vertical coopetition’, which helps to understand the dynamic approach taken by key accounts in managing their relationships with their suppliers.

As we have demonstrated, this vertical relationship is characterized by a combination of cooperation and price competition, but the weight of each antagonistic approach within that combination may be influenced by two major variables: the purchased product itself (reference Kraljic's (1983) seminal article) and, more importantly, the value of the brand or business unit in which the purchased product is incorporated.

Our paper may provide practitioners with a new tool (Figure 2) that will help them to fine-tune their relational strategy:

- Suppliers may assess the coopetitive mix in their relationships with key customers and use it to segment such customers or to define the level of resources they wish to allocate to them. They may no longer have a monolithic customer approach but decide to adjust their key customer relational strategy according to the value of the customer's different final product lines or brands and focus their efforts where they can add and appropriate more value.

- Key customers may also define the coopetitive mix in their relationships with suppliers according to the latters' contribution to the added value of their final products. As defined in our article, the coopetitive mix may be used to segment suppliers as a dynamic approach and an incentive for suppliers to dedicate more efforts to collaboration and innovation.

In short, our research is a pragmatic attempt to fill in the ‘middle’ of the relationship continuum, which has been left blank by academic scholars, and qualify the relationship marketing paradigm with the practitioner's perspective.

Our findings establish the relevance of defining key account–supplier relationships as ‘coopetitive’ and provide a framework for describing such relationships, but as is true of all research projects, this study could be a stepping-stone for further research opportunities.

First, this research programme focused on a limited number of case studies. The key accounts selected are global companies wielding a good deal of power in their respective industries, implying that their suppliers found themselves in an asymmetrical power relationship. It would be interesting to broaden this research approach to other standard customers.

Second, we deliberately chose to emphasize the key accounts' point of view. The perspective of suppliers was taken into account, but only in order to gain a critical insight into the viewpoint of the key accounts. We did not study any specific dyadic relationship or any network perspective. The results of the study would have to be consolidated by taking such perspectives into account.

Third, although we include some ‘users’ from departments other than procurement in our key account informants, the study focuses on buyers, which may have created some potential bias. Further research could deal with this input at a later date.

While the need for further research has to be borne in mind when considering the results of the study, we have nevertheless introduced new insights into customer–supplier relationships that may be of use to both academics and practitioners and offer an alternative to the bipolarization of such relationships in current present scholarship. Further research should attempt to corroborate the results of the study against a broader background (quantitative research) and apply other perspectives (standard suppliers).

Notes

Reproduced with the kind permission of Elsevier, from Lacoste, S. (2012) Vertical coopetition: the key account perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 44(S), 202–218.

1 Some industrial firms have strong product brands (i.e. within the FMCG industry) whilst others, in industrial products, do not have branded products but differentiate their products within the organization of their Business Units.

See Financial Times, http://www.FT.com, Daniel Schäfer (05/08/2009), ‘BMW eyes Peugeot tie-up for Mini.’

2 Industrial Marketing and Purchasing Group – http://www.impgroup.org.

3 As key accounts are strategic customers from their suppliers' perspective, it may be expected they are in power dominant position versus their suppliers, although a study by Caniëls and Gelderman (2007) produces evidence of supplier dominance in which the item being supplied is considered to be of strategic importance. However they admit that this is an unexpected and ‘provocative result’ (Caniels and Gelderman 2007, p. 227).