Drivers for key account management programmes

Abstract

Key account management (KAM) programmes are a way for companies to develop existing relationships and increase sales, thus being proactive and searching for opportunities which are expected of KAM. It is also a way to meet changing customer demands arising from changes in purchasing strategy, buyers' mergers and acquisitions, and the search for synergies in order to reduce costs. This paper analyses the way in which different key account management programmes manage the sales process complexity and customer expectations.

The paper draws on qualitative data collected during a field study of ABB and six of its major customers, based on annual or bi-annual interviews with 50 individuals within ABB from 1996 to 2006, and 3–10 individuals from each of the customers. Interviewees included corporate managers, key account managers and sales personnel/project managers. The customers involved in the study belonged to mining, automotive, process equipment manufacture, building technology, energy production and telecommunication sectors.

In this study three different programmes have been identified and analysed: (1) the proactive programme, which is driven by sales opportunity; (2) the reactive programme, which is driven by customer demands; and (3) the organization-based programme, which is driven by the belief in customer-centric organizational units. With an empirical base the paper provides a basis for understanding the reasons behind the establishment of several KAM programmes in the same corporation. It identifies sales aspects of KAM programmes that are handled in different ways by different types of programmes.

Introduction

Research on industrial sales is very much focused on sales personnel and issues such as sales training that use theories, frameworks and constructs from economics and social psychology (e.g. role stress, ambiguity, motivation, rewards), with a focus on individuals (see e.g. Anderson and Oliver 1987; Bush and Grant 1994; Dubinsky 1999; Dubinsky et al. 1986; Walker et al. 1977; Weitz et al. 1986). Practitioners have, however, pinpointed that effective selling requires the participation of many people, and researchers have addressed cross-functional aspects of the selling process (Cespedes 1992; Cravens 1995; Harvey et al. 2003; Narus and Anderson 1995; Natti et al. 2006; Piercy and Lane 2006; Weitz and Bradford 1999). Furthermore, researchers have also addressed that selling and sales organization influence corporate organizations, and corporate organizations heavily influence the way in which sales can be managed and conducted (Galbraith 1995; Rehme 2001).

Many industrial corporations have reduced their supplier base (Abrahamsson and Brege 2005; Sheth and Sharma 1997) and the implementation of programmes such as just in time (JIT), supply-chain management, efficient consumer response (ECR) and joint product development has resulted in the need for tighter linkages with suppliers. In order for suppliers to cater for these customers' needs, specific approaches to the most important customers are needed. For this, KAM approaches are often used, since the selling process is beyond the capabilities of any one individual and may require a coordinated effort across product divisions, sales regions and functional groups.

The literature on KAM can roughly be said to focus on two different factors. One factor concerns small groups of individuals that are formed to service the key account, i.e. selling teams, selling alliances (e.g. Cespedes 1992; Gladstein 1984; Smith and Barclay 1993, 1997). The studies on selling teams have predominantly been concerned with what distinguishes successful from unsuccessful sales teams. The second focus is more concerned with the management concept of KAM programmes, particularly in connection with buyer–seller relationships (e.g. Barrett 1986; Boles et al. 1994; Brady 2004; Natti et al. 2006; Pardo 1997; Pardo et al. 2006; Rehme 2001; Sengupta et al. 1997; Shapiro and Moriarty 1982, 1984a, 1984b). This means a focus on enhancement of the dyadic business relationships and the effectiveness of the KAM programmes from this perspective (e.g. Cespedes 1992; Lambe and Spekman 1997).

Key account management is here defined as the organization that caters for the management and the development of the relationship, in a more or less formal structure. As such it follows that the seller's marketing strategy involves deliberately forming a structure for the largest and most important customers, with the intention to move from interpersonal relationships to group-on-group relationships (cf. Narus and Anderson 1995). Consequently, it can be regarded as the industrial firm's policy to assert that the most important customers really are treated with special care, as an organization with the responsibility to do so is assigned to them. With the exception of the conceptual discussion in Harvey et al. (2003), the literature on KAM seems notably to have missed any discussion on whether KAM is initiated as a proactive, management-driven and opportunity-based solution, or whether it is formed reactively in response to customer needs and wants. KAM is consequently an important ingredient for international and global corporations' sales organizations.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the reasons behind why key account management programmes are formed within corporations, and what factors become important for different types of programmes. Particularly it sets out to understand the development of the key account management organization over time, with a focus on external and internal factors on a company/corporate level. To our knowledge there has been little research covering the development of KAM programmes, particularly following one corporation with both a national and an international scope.

This paper is organized as follows: the next section reviews previous literature on key account management programmes. In the following section the KAM framework developed from previous literature is described with triggers and drivers, as well as a tentative model on the complexity that is present in the industrial sales which KAM programmes tend to handle. A short description of the three programmes follows and the subsequent section contains the analysis. The final section presents conclusions and describes the need for KAM programmes to be able to handle multiple sales situations.

Key account management

The concept of KAM programmes has been developing since the 1960s (Weilbaker and Weeks 1997). It was first designed to handle geographically dispersed customers, with multiple locations, in a systematic manner. Although the approach and content have changed over the years, the international trend of KAM was strong from the 1970s to the 1990s as well as throughout the beginning of the 21st century (cf. Boles et al. 1994; Brady 2004; Natti et al. 2006; Pardo et al. 2006; Weilbaker and Weeks 1997).

Key account management is often defined as a managerial response to sales to large customers. The common denominator in the description of this type of selling is the focus on selling more to established customers, who are significant to the extent that the sales to the specific customer account make up a substantial part of the selling companies' turnover (e.g. Stevenson and Page 1979; Weilbaker and Weeks 1997). Since these ‘accounts’ purchase a great deal, or have the potential to do so, they represent great sales opportunities, but also, if they already purchase substantially, a great risk (Piercy and Lane 2006; Shapiro and Moriarty 1982). To manage the opportunities and risks it becomes important to try to establish tight and long-lasting relationships with these major or key accounts.

KAM and related terms mean to grant the largest and/or most important customers special treatment since they require special attention (cf. Barrett 1986; Sharma 1997). Shapiro and Moriarty (1982) add that ‘a supplier seeks to establish, over an extended period of time, an “institutional” relationship, which cuts across multiple levels, functions, and operating units in both the buying and selling organization’. The term key account management depicts a situation where large customers are handled quite differently from the other customers, inasmuch as there are appointed salespeople, account managers and other dedicated relevant personnel who form the interface to that customer. In other words, this means that there is a selling-side organization that is formed to cater for the special needs of one or more large customers. Particularly, we define a key account management programme as the organization that is formed for large and complex customers where some sales effort coordination is required.

KAM is a way of having one single salesperson, or a sales team, responsible for one major account in a region, one country or globally. One of the benefits for the buyer in having one single salesperson is that the buyer needs to contact only one person, and another is that there may be uniformity in prices for the buyer's divisions even if these divisions are geographically scattered. For the seller, this is a way of ensuring continued orders from the customer. The reason for the continued orders could be the selling company's ability to solve problems, since it now has one dedicated salesperson for each customer who is very knowledgeable about the customer's entire operations (Weilbaker and Weeks 1997). As Natti et al. (2006) debate, KAM can be seen as a knowledge transfer system integrated in the customer management system.

Benefits of key account management programmes

As mentioned initially, the literature on KAM can be said to focus on two aspects, namely sales team articles and KAM programme articles. Studies on sales teams have identified what distinguishes successful from unsuccessful teams. The distinguishing factors include trust, open communication, perceived interdependence between team members (Gladstein 1984; Smith 1997; Smith and Barclay 1997) and issues such as empowerment of sales teams (Perry et al. 1999). Articles on KAM programmes have had a focus on dyadic business relationships (Cespedes 1992; Lambe and Spekman 1997). The questions raised in these articles include the benefits of KAM programmes, the customer's perception of KAM, the people involved, the division of interests and the organization of KAM programmes. Among the benefits of a KAM programme are improved relationships between buyer and seller and thus an increase in sales share, improvements in buyer–seller communication, better quality in sales calls, etc. (Barrett 1986; Boles et al. 1994), but it also incorporates business risks of becoming more reliant on fewer and larger customers (Piercy and Lane 2006).

In an issue of Thexis in 1999 there were several insightful studies on how particular companies are managing their key accounts (Millman 1999; Momani and Richter 1999; Wilson 1999). These articles identified drivers that the KAM programme aims to handle, such as shortening distance between seller and buyer (location is shifting to create greater geographical distance), focus on shortening time (coordination, rapidity, timing owing to logistic focus in terms of JIT, ECR) and demand for spreading best practices. Building on Nahapiet (1994), Yip and Madsen (1996) reported that the key driver of account programmes was demand from the rapidly globalizing procurement functions of customers. Using contingency theory, they suggested that a number of industry- and firm-specific factors determine the likelihood of a company forming a key account programme, and of the programme contributing to the successful implementation of global marketing strategies.

Key account management has been credited with a number of benefits. Generally speaking, customers appear to be positive to the KAM approach (Pardo 1997; Pardo et al. 2006). More communication and closer relations (Barrett 1986; Boles et al. 1994), but also more tangible results, such as market and customer share and profits, have been cited as benefits of KAM (Brady 2004; Stevenson 1981). Other identified gains are the development of trust (Doney and Cannon 1997; Smith and Barclay 1997), increased information sharing (Frazier et al. 1988; Mohr and Nevin 1990), reduction of conflicts (Gundlach and Cadotte 1994) and commitment to maintaining the relationship (Achrol 1991; Mohr et al. 1996; Morgan and Hunt 1994).

Internal and external driving forces for KAM programmes

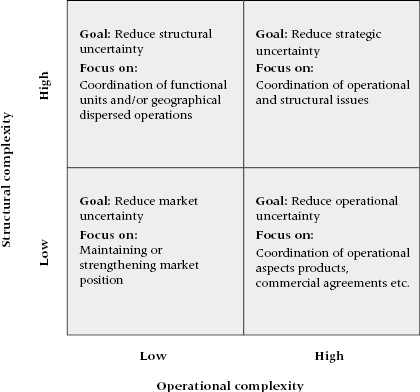

Although the perceived and realized benefits from KAM programmes can be regarded as the rationale as to why companies form these programmes, there are other driving forces that can affect the way in which these programmes are formed, as well as the factors that become important. Naturally enough, the majority of literature has been from the selling firm's viewpoint (e.g. Barrett 1986; Boles et al. 1994; Kirwan 1992; Tutton 1987; Weilbaker and Weeks 1997), but some articles do cover topics from the customer's viewpoint (e.g. Pardo 1997; Pardo et al. 2006; Sharma 1997). The focus of most KAM programmes described is on improving the efficiency and effectiveness of present sales and customer relations. Key factors behind the popularity are promises of dramatic improvements in sales based on a better knowledge of the purchasing demands. The affecting factors are partly internal issues in the selling company and partly related to customer purchasing, i.e. external factors to the KAM programme – see Figure 1 (cf., for example, Cespedes 1992).

Figure 1 The affecting factors in KAM programmes

The external factors are defined as those that are outside the control of the selling organization and include the purchaser's situation and general environmental conditions and factors. Jones et al. (2005) discuss the external factors affecting sales forces in terms of four categories of influences: customers, competitors, technology and the ethical and regulatory environment. The internal factors are here defined as those factors that are under the domain of control (or appear to be) for the selling organization. This includes the internal organizational issues, as well as the marketing strategies and operations that are handled within the seller organization for performance improvements. The aim is to focus on internal factors that target external factors to drive company performance as well as outperform competitors in creating a better sales offer. Although external factors are outside the direct control of the selling organization they may affect the internal structures and processes (cf. Eisenhardt 2002; Harrigan 2001), having important implications for the focus of the account management. Actions of the seller organization that aim to target internal affecting factors can also affect external factors. KAM programmes are thus regarded as an organizational unit, virtual or formalized, that is directed to handle internal and external factors, and in particular complexities in and between the selling and buying organizations.

Managing industrial sales complexity: A tentative framework

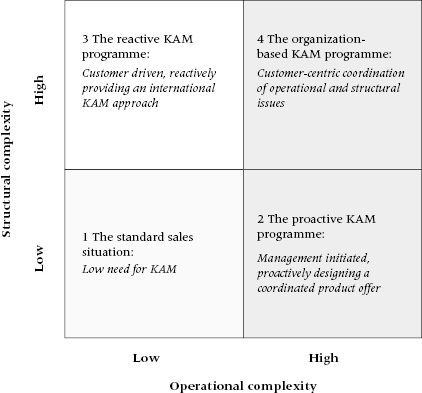

Establishing KAM programmes can, as Jones et al. (2005) discuss, be seen as a way to handle different forms of complexity that derive from internal or external factors. In an article on project complexity, Williams (1999) suggests that, in order to support the management function – in particular planning, forecasting, monitoring and control – it is vital to model the complexity present. Williams structures the complexity in two dimensions. The first, based on the work of Baccarini (1996), is structural complexity. This applies to different sales dimensions, such as decision-making, management processes, environment, technology, organization, etc., that are to be handled through the organizational structure or by bundling or unbundling the technical complexity of the products and service through the account management. The other dimension involves the complexity originating from the uncertainty present in the sales process.

Uncertainty concerns the instability of circumstances and assumptions upon which decisions are made. Håkansson et al. (1977) describe three types of uncertainties for a buyer, and how these are changed during interaction between buyer and seller. Need uncertainty is about uncertainties connected to the levels of demand, and increased interaction might increase or decrease the level of uncertainty. Market uncertainty is related to the suppliers themselves, while transaction uncertainty is about the physical transfer of the products from supplier to buyer. In their article they maintain that the buyer strives to keep the uncertainties as low as possible. As a consequence, it becomes important for KAM programmes to be designed so that the uncertainties can be decreased or at least managed, otherwise the complexity might be impossible to manage. Shapiro and Moriarty (1982) and Andersson et al. (2007) also discuss complexity in term of structural and operational dimensions. Based on these authors' discussions, complexity in a KAM setting could be defined along the following dimensions:

The selling organization can be complex along the same dimensions. In order for the KAM to be able to set up a coherent offering, the KAM may need to coordinate geographic dispersion in the seller as well as the buyer organization, manage a variety of goods and services and sometimes entire systems, as well as facilitate logistics solutions for the delivery of these offerings to the customer. In this respect the KAM programme is a tool to decrease the uncertainties in the buyer–seller relationship by coordinating the offering to the customer. Based on different complexities, the focus of the coordination may vary (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Sales complexity management matrix

In a situation with both low operational and structural complexity the goal should be to reduce the market uncertainty (cf. Håkansson et al. 1977) by clarifying the seller's dedication to be long term and their seriousness as well as commitment to the relationship. The lower left quadrant in Figure 2 concerns the importance of the infrastructure for handling uncertainties during the sales process. It is questionable whether a KAM is needed for this situation since the coordination requirements are low. However, KAM might prove to be a tool to clarify the seller dedication to the customer.

Operational complexity may affect the customer expectations, as in the lower right quadrant in Figure 2, especially in situations where the customer has clear goals and involves the selling organization in design-and-manufacture projects with goals formulated by the customer and accepted by the selling company without discussion. The product structure is a common explanation behind long lead times, high cost of planning, coordination and control, which is also a reason for forming a KAM organization (Homburg and Pflesser 2000). From a KAM perspective, the goal should therefore be to reduce the operational uncertainty by focusing on managing and coordinating aspects related to operational complexity that is a result of many product varieties, complexity in logistics solutions, etc.

High structural and low operational complexity mean that the seller needs to focus on the coordination of organizational units. The industry context affects the structural complexity that causes uncertainties for the customers, that needs to be managed, as in the upper left quadrant in Figure 2. Sales management must subsequently adapt to contextual prerequisites such as national cultures, corporate cultures and external stakeholders' demands.

High structural and high operational complexity means that the focus is to coordinate both operational and structural issues. The goal is to reduce what we have termed ‘strategic uncertainty’ and involves comprehensive coordination. Harvey and Speier (2000) use the term ‘relational richness’ to capture the net uncertainties in the KAM relationship, and as Natti et al. (2006) observe, knowledge sharing and integration are of great importance from a long-term perspective.

Research method

The paper draws on qualitative data collected during a field study of ABB and six of its large customers. The study is part of a longitudinal study of the management of industrial sales, its development and its effects on strategy, relations and customers. Since ABB is an international and global corporation with a presence in all regions of the world, we limited the focus in this paper to the European continent and focus here on examples from the Nordic countries, Ireland, Germany and the UK. The customers in the study belong to mining, automotive, process equipment manufacture, building technology, energy production and telecommunication sectors.

With 50 interviewees we conducted 2–3 interviews within ABB from 1996 to 2006 and with each of the 6 customers 3–10 interviewees were interviewed 2–3 times. Interviewees included corporate managers, key account managers and sales personnel/project managers. The three-layered interview design was explicitly planned to gather data on the same topics from different hierarchical levels. We did not develop performance measures to assess the effectiveness of the three different key account management programmes. Interviews were semi-structured and lasted between 90 minutes and 3 hours. In addition we participated in annual European sales managers' conferences arranged in order to share experience and customer knowledge and inform on strategic changes.

Data from these interviews were elaborated to produce mini case studies of the three KAM programmes as well as the customers involved in the study, enabling identification, evaluation and matching of patterns as they emerged from within individual cases (Eisenhardt 1989). We then cross-compared the mini cases to identify common patterns in the account management programmes. Following Gummesson (2005), we worked with comparisons, condensing the data in order to identify patterns and independent variables to preclude the presence of other independent variables of the three KAM programmes. The use of the pattern-matching tactic strengthens the internal validity of the research. Here the multiple case research design is of importance as the multiple empirical setting contributes to high external validity (Gummesson 2005).

Three key account management programmes at ABB

KAM programme – ABB Swedish Market

In order to deal with the coordination problems for the Swedish market, senior management in ABB Sweden initiated a project entitled ABB Swedish Market (Svensk Marknad). ABB Swedish Market was formed officially in 1996 (although it was initiated earlier). It consisted of the Swedish ABB companies and their sales organizations. For the strategic development of ways to work within specific customer segments and towards specific customers, the market for ABB in Sweden was divided into nine industry segments:

Instead of operating through the internal ABB segment structure, this was an attempt to divide the market from a customer perspective. For each industry ‘segment’ there was one principal company, i.e. one ABB company, assigned. The principal company employed the industry segment manager and together they held responsibility for the strategic development of the business within the designated industry.

In the different industry segments, a number of KAM teams were formed, consisting of sales people from relevant ABB companies covering that particular customer. The team members each represented one ABB sales organization. The KAM teams were given the task of focusing on the processes and applications of key customers in order to be able to supply as correct a solution as possible regarding that specific customer.

The key customers were all large, or potentially large, customers. It was especially important to focus on customers with which at least one of the ABB companies had good relations, and where there were opportunities for other ABB companies to move in. Not uncommonly this could be the case in many of ABB's customer relations, and subsequently this was seen as an opportunity for the ABB group to expand sales in the Swedish market.

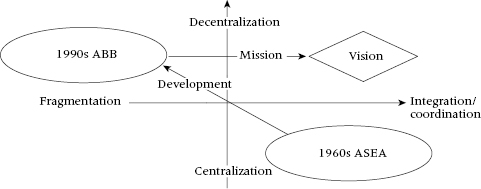

The forming of a geographical divide, industry segmentation and KAM teams was not intentionally designed to change the organization. The ABB companies were meant to function as separate entities, then and in the future. The project could be seen as something of a ‘virtual organization’, with the intention to develop the way ABB approaches the Swedish market. This is a ‘best of both worlds’ vision, to coordinate sales efforts but retain the benefits of the decentralized organization – see Figure 3.

Figure 3 The development of ABB sales (ABB internal material 1996)

One of the main assumptions of this work was the need to have good and visible contacts at all levels in the customer's organization. Since one of the major aims was to address large customers, it meant that normally the customer's organizations were fairly complex, so enjoying good relations with a customer could mean only for one specific part or department of the customer's organization.

In October 1996 the ABB Sweden management presented a leaflet in which the ABB Swedish Market's strategic goal and vision were presented. It outlined the importance of Sweden as an ABB home market and that this market was changing:

“The customers are concentrating on their core business and therefore demand simplicity and more comprehensive solutions.” (ABB leaflet on strategy and action)

In strategic terms, the ABB Swedish Market's development and the current task were expressed as the:

“[Development] from a centrally controlled ASEA to a decentralized organization with ABB companies. Our task is to move towards a more coordinated ABB, a network, whose primary task is to simplify things for the customers and help the customers with total solutions, without changing the good things with our decentralized organization.” (ABB internal material translated)

In the same leaflet an action plan in three steps presented the ABB management view of the content of this work:

ABB Swedish Market was clearly a top management initiative. The focus of the approach was to create simple contact for the individual customers. The managing director for ABB in Sweden described it thus:

“An important principle is to always try to make the relation as simple as possible. That is the basic idea for ABB Swedish Market. The intention is that for you as a customer, provided you do not need contacts with specialists, it should be sufficient with one contact person at ABB.”

Moreover, the preconceptions on which ABB Swedish Market rested were:

The ABB Sweden customer base had some interesting characteristics. One estimate from ABB concluded that the division of customers was disproportionate with regard to large and small customers. Of an estimated 11,000 ABB customers in total, only 50 were said to account for approximately 60% of the ABB Swedish sales. When the company looked into this in greater detail it discovered the total customer base to be in the region of 40,000, where 100 customers accounted for 60% of sales. After the divestment of the distributor business in the Nordic countries, i.e. ASEA Skandia, the top 100 customers were accounting for almost 80% of the total sales. With such an asymmetric customer base, there was obviously a tendency to prioritize the large customers over the small.

KAM programme in the ABB business area for industrial products and systems

The ABB business area for industrial products and systems had several coordination groups especially aimed at coordinating efforts for international customers. International customer coordination was seen as one way to try to win these large accounts, by starting initiatives towards these customers.

In 1992 the business area started a distributor coordination project for its largest wholesale customers in order to be able to follow the international expansion of those customers. In 1995 the business area ‘low-voltage apparatus’ started another project called Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) Customer Coordination, which followed international OEMs' business. In 1998 ABB combined the two key account projects into a common key account organization for both distributors and OEM.

Whereas market segmentation was a way to understand the needs of different customer groups, in particular with regard to the technical requirements and their application needs, key account management was a way of paying special attention to large customers and their specific needs. From a selling company perspective there might be more issues that are common to different large customers than there are to companies belonging to the same application segment. The major determinant for ABB to coordinate sales activities, however, was from the beginning to achieve door-openers to customers with operations in different geographical markets and to benefit from benchmarking within different application segments.

The work for the coordination of international accounts was divided into two different tracks, one for OEM customers and one for the electrical wholesale business. For OEM the international accounts were subdivided in accordance with their application needs into a number of segments. The idea was to have one coordinator for each of these segments to be responsible for the coordination of all international accounts within the same segment. All in all 20 international accounts for the OEM segment were active at the same time, whereas the wholesaler international KAM programme was for 10 customers.

For the coordination of international OEM customers there was a group for the facilitation of international key account management. This group consisted of 12–15 international and national key account managers from Europe and the USA, who met on a regular basis 3–4 times a year, with a special focus on a few selected OEM segments (windpower, HVAC, generator sets and drives). They had around 20 KAMs under their wings. One of the major drivers for the group was to take advantage of the application segmentation and use this knowledge to reach other customers within the same OEM segment.

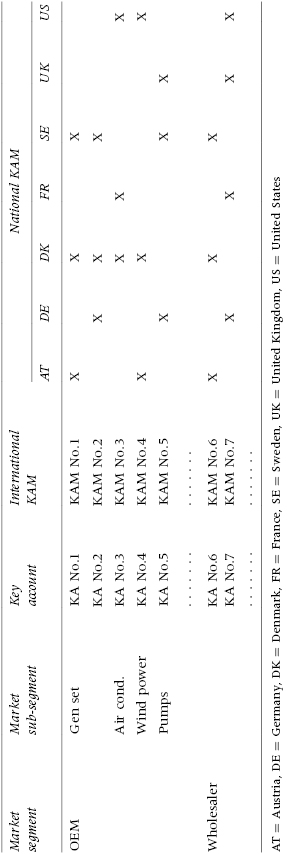

Each account had one international account manager responsible for the ABB contacts with the whole customer organization. In each country where the customer had local presence, the organization assigned one national key account manager. The national key account managers were responsible for the day-to-day needs of the customer business, as well as for keeping track of movements and activities that might have changed the way in which the customer wanted to do business. Furthermore, whereas the international KAM was responsible for the strategic partnership, and thus agreements, the national key account managers were responsible for the local partnership agreements – see Table 1.

Table 1: The schematics of ABB international customer coordination, the segments and the KAM programme

The international key account managers came from both producer companies and pure sales companies, where one key element determining who should be assigned as KAM was the location of the businesses' headquarters, although a few of the KAMs also came from production companies outside the headquarters' country, particularly when there were special needs that could be resolved only with producer intervention of some sort. The overriding determinant for international KAM was still, however, the main location of the customer's business. Furthermore, the majority of key account managers had more than one assigned key account, both nationally and internationally. Some of the account managers had the KAM work merely as a part-time assignment whereas others were kept fully occupied by it.

Key account management for organizational reorientation

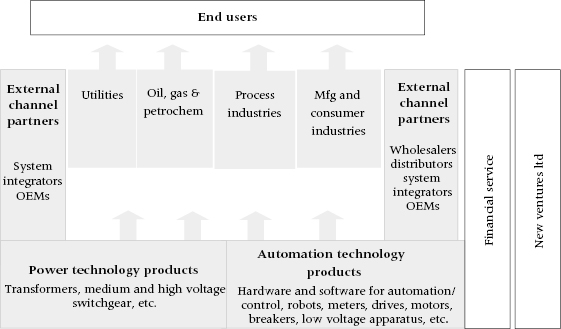

In November 2000 ABB announced a change of chief executive officer. The new CEO was appointed in January 2001 and this signalled a major reorganization scheme for the whole group. This new organization was based on four application-oriented industrial segments and two product segments – see Figure 4.

Figure 4 The 2001 organization (ABB internal material 2001)

In this layout the product segment, i.e. Power Technology Products and Automation Technology Products, contained all the producing companies, which were transformed into divisions within either Power Products or Automation Products. This organization was implemented throughout the ABB world. The product segments were to be responsible for product development, production and production-associated operations.

The application-oriented organization was based on the customer segments manufacturing and consumer industry, process industry, oil, gas and petrochemicals and utilities. This organization became responsible for all selling, relationship-building and application-oriented systems and product development in their respective industry segments. It contained the KAM organizations, which became even more important. The basic idea was that the producers were to sell their products or systems via the customer segment sales organizations. An exception to this was the supply to wholesalers and OEMs, etc., which would be taken care of by the product segments themselves. A remnant from the former organization was the business area structure. The producers were measured by their performance in the individual customer segment and by business area, but not as separate entities.

This was the biggest organizational shake-up since the merger between ASEA and BBC into Asea Brown Boveri Ltd (ABB) in 1987. It was based on certain assumptions. First, it was more important to be customer- and customer-application oriented than previously. Particularly in order to supply an industry segment with systems or entire plants, this organization was meant to be equipped to deal with the coordination of ABB activities and products. Second, globalization of the business was increasing and the organization re-emphasized this fact by strengthening the international KAM programme. Third, it addressed the issue of differentiation and fragmentation experienced both internally and externally. The predominant factor underlying this was the formation of larger units for the producing divisions and the coordination aspect in the sales divisions.

The reorganization also entailed problems and challenges, particularly related to the centralization component in the new organization. Ultimately, the global KAM programme defined 30 global customers as key accounts with top executive sponsors, thus clarifying the strategic importance of these customers for the ABB group.

KAM programme drivers

Low purchasing coordination and low sales coordination in some respects constitute the starting point of this study. Both seller and buyer are organizations that are large and highly divisionalized. Neither purchasing nor sales were coordinated to any great extent, which basically also fitted the individual relationship fairly well since both of these functions were specialized and thus fairly narrow. When either the buyer or the seller moves in a direction towards coordination the relationship has a less structural fit and neither experiences the complexity present as a problem. When the buyer takes action it is fairly natural for the seller to react to the new customer demands and thus coordinate their sales operations. When the seller initiates actions for sales coordination in order to reduce some complexity dimensions it is difficult to persuade the buyer to coordinate purchasing operations. Instead it is more likely that the seller tries to adapt to the buyer's organization, maintaining coordination in the sales operations. This makes sales task completion more complicated and increases the complexity in the sales process. In cases with joint actions, the actions and reactions are made reciprocally.

In the ABB Swedish Market case it was ABB that had been pursuing the issue of coordination prior to any clear customer requirement to do so. This is a clear indication that this ABB sales organization in some respects was leading the way for these approaches, and in some instances has actually created the prerequisites for altering its customers' way of buying products.

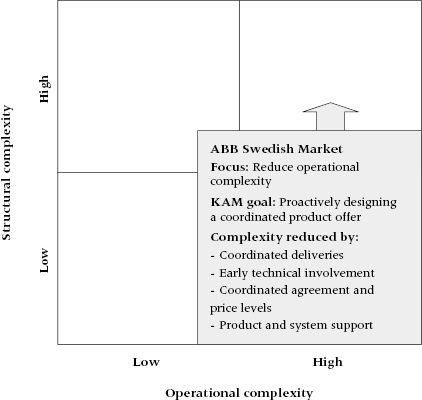

ABB identified that a number of its customers experienced technical problems as a result of the current purchasing strategy, problems that were impossible to overcome without coordination of sales activities. The programme was thus formed to support system selling or selling of technical solutions that includes a number of new products or services from other companies in the ABB group. In ABB the focus of the KAM programme and its managers was mainly on establishing and managing an internal cross-divisional sales organization in order to increase the sales for the group and creating an awareness of the competences that ABB had, so that each sales engineer had the ability to channel business opportunities to the right ABB division. Consequently, the characteristics of each KAM differ since they aim to reflect the characteristics of each customer, focusing on a combination of goals formulated in terms of technical problem solving, a reduction in the customer supply base or business opportunities for ABB. The focus of the KAM programme has been to anticipate these customers' buying organizations' efforts in coordinating their purchases between different units – see Figure 5.

Figure 5 The sales process focus of the Swedish Market programme

The focus for this programme was the coordination of products and systems to create a more complete ABB offer to key customers. The idea was to make the product and structure simpler by forming KAM teams, and from a customer perspective make both the technical and commercial offer less complex. However, by starting this programme the complexity in coordinating technical and commercial issues increased for the internal ABB team (depicted by the arrow in Figure 5), thus increasing the structural complexity since the programme puts pressure to coordinate an uncoordinated organization.

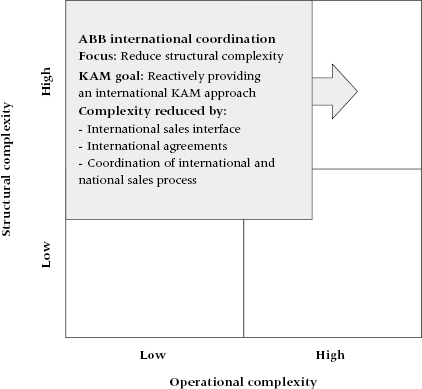

In the international KAM programme the situation was somewhat different. The buyer drive for this programme was relatively strong. Furthermore, some of the relationships that constituted the reason for the programme contained elements whereby the buyer laid coordination requirements on the seller organization. This meant that the buying organization produced a more integrated way of organizing the purchasing organization. It was therefore the buyer organization's dedication to purchasing coordination that resulted in more ABB sales coordination within the realm of the KAM programme. For example, ABB had an established relationship with a customer but the customer demanded not only the supply of parts but also that ABB should pre-assemble the parts into sub-systems. This required competences of several companies in the ABB group and the KAM programme was set up around the specific project/solution – a temporal solution-based KAM programme.

Furthermore, in instances of a joint action in the formation of KAMs, there appears to be a joint effort also in trying to achieve benefits from the programme. The rationale for moving towards more sales coordination when the buyer organization is coordinated is much stronger than when sales coordination influences purchasing. A result of this is that customers who have experienced the benefits of the temporal solution-based KAM programme compare how they have been approached in different geographical or product areas. Hereby the buyer often spots commercial gains if the selling group coordinated their offer, products and services worldwide. For the ABB group this means that a KAM programme must be established, initiated by the customers' demand for decreasing the costs, to identify in which way the customer is to be approached and to establish a common way initiated by the customer – redundant activities and sales work have to be changed. The programme also aims at commercial coordination on a group level and consequently there will be few possibilities for geographical and product companies to be unique, increasing the operational complexity – see Figure 6.

Figure 6 The business area KAM programme

This programme had a focus on coordinating geographical units, thus making the commercial deal more consistent and, from a customer perspective, less complex. This means that the sales processes become more complex, since the sales have to be handled on different levels and at different locations in the customer's organization (depicted by the arrow in Figure 6). Much of this complexity stems from the geographical dispersion and the resulting geographical coordination that is emphasized in this programme. From the customer perspective, commercial and market complexities are expected to decrease with the introduction of this programme.

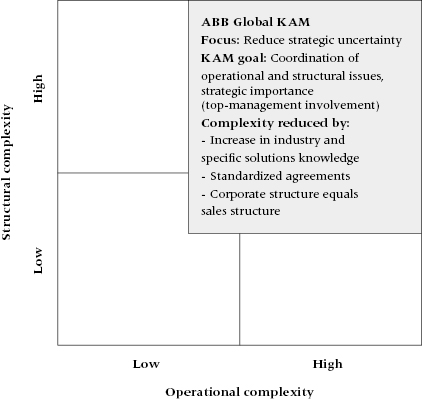

The Global KAM programme was initiated as a response to changes among customers in different industries, characterized by tighter economic conditions, in order to increase their competitiveness, common legislation in several countries regarding standards (i.e. electricity safety standards), deregulation of industries and markets as well as the introduction of more advanced technology. The focus was to coordinate a large variety of products, commercial agreements and fulfilment systems across different units as well as national borders.

The requirement laid on ABB, as a supplier of parts and sub-systems, was to take responsibility for the customers' final products, manufactured at different locations, functioning together independent of the intended market. Mergers among ABB customers led to a more polarized and divided market, with on one hand large global companies and on the other small local companies. For ABB, its products and solutions were still the basis of the offering, but to be a competitive supplier to the large customer the company also had to understand the requirements that its customer faced in its markets. To do that, the KAM organization had to be present in all parts of the world and be relatively more customer- than product-centric. Consequently, an organizational structure based on the key customer's demands was formed to gain internal coordination through dialogue and communication of customer requirements, identifying areas to increase sales. This also appears to be a development from the preceding KAM programmes, which developed to become designed to manage both structural and operational complexity – see Figure 7. The Global KAM also entailed increased importance for 30 global customers that all required top management attention, making the KAM a strategic important sales action.

Figure 7 The Global KAM programme

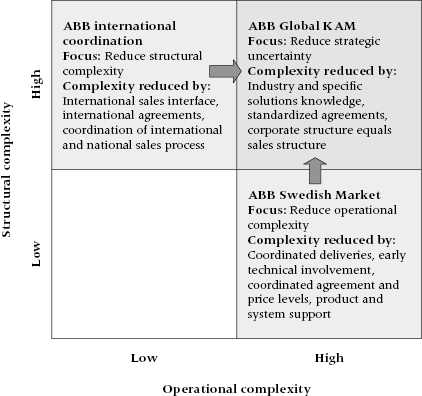

By implementing KAM programmes in buyer–seller relationships the complexities change over time. Furthermore, it becomes important to manage these uncertainties in order to achieve the benefits that are associated with KAM programmes – see Figure 8. For different types of programmes, the complexities are different, and the way in which they are managed differs. There are two factors that stand out (cf. Shapiro and Moriarty 1982):

Figure 8 Complexity and KAM programme development

These two factors have had a substantial impact on the design of the programmes. The reasons behind the different programmes have also differed where the structural complexity has been caused by a response to customer requirements, whereas product complexity was based on a proactive implementation of a KAM programme. For the Global KAM the coordination becomes a highly strategic issue for the ABB group, thus involving top management to reduce the strategic uncertainty.

Situations that entail both low operational and structural complexity (low–low) have not been reported in this study since this is a sales situation that will not benefit from KAM programmes. This is not surprising since the coordination requirements are low both in structural and operational dimensions.

Conclusions

Although there is much talk about having customer focus and pursuing customer-centric marketing, there are still large discrepancies between the marketing strategy and the way buying companies perceive their own role. Whereas the focus on the buying counterpart is aimed at cost reductions, sales organizations' primary focus is on selling more. In marketing strategy, reducing total costs in the relationship is not the first priority. This reasoning is very much associated with the marketing and purchasing strategies encountered in the buyer and seller firms. The marketing strategies contain the focus on systems and international selling as well as the focus on customer share. Similarly, the purchasing strategy contains the coordination of corporate purchasing nationally and internationally as well as the degree of functional buying. This also means that marketing and purchasing strategies are important reasons for KAM programmes being established.

Coordinated purchasing and selling may be perceived both as a structural issue, i.e. how we structure the organization, and a strategic one, i.e. how we want to direct our efforts in purchasing and selling. This also boils down to the long-debated issue of strategy and structure and their effects on firms (cf. Chandler 1962, 1998; Harris and Ruefli 2000). The ability to coordinate is strongly affected by the structure in the firm, whereas the strategy directs coordination efforts.

Particularly interesting with regard to this is the strategic/structural fit between buyer and seller in the different KAM programmes. This was seen especially in respect of action and reaction towards coordination. Buyer action to coordinate purchasing results in considerable importance for sales coordination and thus KAM programmes, whereas solely seller-initiated KAM programmes entail more organizational adaptations from the seller party, since it appears to be more difficult to persuade buyers to coordinate their operations on the basis of the seller wanting it. Moreover, in a seller-reactive programme the KAMs are more compelled to do the coordination and are thus more focused in their efforts. In a proactive programme the efforts to be coordinated are less defined and therefore need to span a larger scope, at least initially.

Furthermore, whereas seller strategy in KAM programmes is directed towards selling more by being the preferred or sole supplier (cf. Barrett 1986; Shapiro and Moriarty 1982), buyer strategy is more often than not aimed at cost reductions by development of closer supplier relationships (cf. Dwyer et al. 1987; Kalwani and Narayandas 1995). This means that in a reactive KAM programme the coordination is directed more by the customer requirements, whereas a proactive KAM programme is more reliant on a teamwork coordination containing a larger scope, but also more opportunity based. From this proactive/reactive perspective, three different types of KAM programme focus can be discerned.

In the division between proactive and reactive KAM situations there are strong indications of differences with regard to competitive force. In a reactive situation the seller organization needs to be able to respond to a demanding customer, be it for an international commercial deal or for individual projects, since the customer has the initiative. In a proactive situation the seller organization, although subjected to competitive forces, has more leverage in trying to present an attractive offer to the customer, thus avoiding directly comparable competition. In the proactive situation the knowledge base is important to handle matters in a coordinated manner that combines the system-wide resources and capabilities in unique ways to provide more value through the offerings to its key customers (Teece et al. 1997). The dynamic capabilities of the supplier are based on internal resources of knowledge (in some situations scattered in different organizational units) and market awareness, which the competitor will find very difficult to replicate, imitate or trace the origin of. This is KAM providing a competitive advantage compared with its potential rivals based on the specific features of each market/customer.

Whether or not coordinated selling, or for that matter purchasing, is more related to structure than strategy is not that easy to discern. We acknowledge that there can be strategic considerations from top management that distribute power and mandate in the organizational structure of the company. This means that the structure enables the coordination of KAM sales and therefore also the implemented marketing strategies. The strategy behind the establishment of the KAM programme has to be incorporated in the strategy and business scope of the entire enterprise, otherwise it can harm the effectiveness of the supplier (Weilbaker and Weeks 1997).

We show that KAM programmes are established for a number of reasons and that different dimensions direct the workings of the programme towards addressing different terms of complexity. One is that KAM is supposed to handle sales complexity in terms of structural aspects and uncertainty. KAM should also be a response to external aspects, deriving from customer expectations, as well as a way to handle internal aspects in the sales process (see Figure 1). In this study four different strategic dimensions have been identified, resulting in conditions requiring different types of KAM programmes (see Figure 9):

Figure 9 The four strategic dimensions and resulting KAM programme development

The fourth dimension and resulting KAM programme requires the strongest commitment from the corporate leadership, where KAM becomes one of their top priorities.

Performance implications of new ways of organizing marketing and sales activities have been examined in a number of contexts (Anderson et al. 1994; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Workman et al. 2003). The development in KAM practice has gone from being an over-layered dimension in the organization to a situation where KAM is one of the main dimensions in the corporate structure (e.g. Galbraith 1995; Rehme 2001). Subsequently, KAM has also developed from being mainly an operational sales coordination topic to a strategic coordination for the entire organization. The main motivation behind this is that it is becoming a prerequisite to coordinate the corporate structure from a customer perspective to be able to handle large global customers.

Studying an organization over time makes this development fairly clear. More often than not KAM programmes are established by top management with the notion to increase sales to already established customers in local markets. When customers demand more coherent and coordinated international contracts, this drives the establishment of international KAM programmes and thus coordination across national borders. With the potential to handle both the internal shortcomings and the external needs emanating from customer development, it is logical that the KAM programme is integrated in the corporate structure. In this sense KAM is both a strategic platform for the sales organization and a part of the overall organizational design. From being a sales opportunity, KAM is thus developing to become a reaction to larger customers' centralization or coordination of purchasing. As Piercy and Lane (2006) observe, this development, if not carefully handled, could involve a number of hidden risks that can restrain the strategic development.

Note

Article reproduced with the kind permission of Emerald Group Publishing: originally ‘Brehmer, P. & Rehme, J. (2009) Pro-active and reactive: drivers for key account management programmes, European Journal of Marketing. 43(7/8), 961–984.’