Making the case for managing strategic accounts

Abstract

This paper argues the case for the adoption of account management programmes by first recognizing that all firms in business-to-business markets have a relatively small number of customers (current and potential) that are critical for long-run future health. Because they are so important, the firm should treat them better than it treats its average customer. It further argues that traditional go-to-market strategies are under pressure from a range of environmental and customer-related factors, leading to fragmentation of the traditional system, and that this system will remain but two additional systems are forming – for small customers and for key, strategic and global customers. For the effective implementation of KAM programmes companies must achieve agreement or congruence between the four key organizational elements of strategy, organizational structure, systems and processes, and human resources.

Introduction

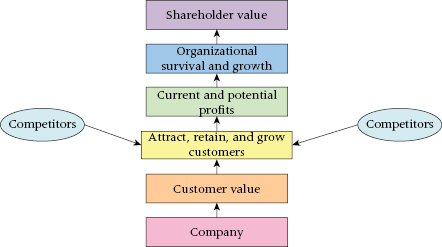

The best place to start in making the case for managing strategic accounts in a business-to-business (B2B) environment is with the fundamental business model (Figure 1). This model assumes that the basic operating task for managers and their companies is to make profits today and promise profits tomorrow. If the firm is successful in this task, it will survive and grow, and shareholder value will increase. However, if the firm is unsuccessful in making profits for a sufficiently long time period, it will eventually go bankrupt and likely be forced out of business. Hence, consistent operating success in making profits enables the firm's survival and growth, and leads to enhanced shareholder value.

Figure 1 The fundamental business model

The managerial imperative to make profits is all well and good, but the causal relationships laid out in the top part of Figure 1 beg an important question: What does the firm have to do to make profits today and promise profits tomorrow? The answer is extremely simple but very powerful: the firm must attract, retain and grow customers. The firm succeeds in this task by delivering value to customers – the vertical dimension of the figure. But merely delivering value to customers is insufficient. The value that the firm delivers must be greater than the one its competitors deliver so that it may secure differential advantage. Securing differential advantage provides the firm with some level of monopoly power (Lerner 1934) and allows it to earn profit margins that exceed the going interest rate.

It is all well and good for the firm to secure differential advantage and to attract, retain and grow customers, but all customers are not equal; some customers are more equal than others (Orwell 1945). The customer revenue distributions of most firms are skewed, following a Pareto distribution (Davis 1941) – more popularly known as the 80:20 rule. In this formulation, 80% of the firm's sales revenues derive from 20% of its customers. Of course, this rule is not exact: for some firms the ratio may be 70:30 and for others 90:10, or even more skewed. (And we should not just confine ourselves to current customers; some customers that provide small revenues today may join the 20% important customers within a few years.)

The implication for the firm is quite straightforward: if a large percentage of revenues derive from a small percentage of customers, then those relatively few customers should receive a disproportionately large amount of firm attention and resources. But where should the firm locate these resources? That is also quite straightforward: if the 80:20 (70:30) rule is true, then the 20:80 (30:70) rule must also be true – 20% of firm revenues derive from 80% of the firm's customers. In general, these 80% of smaller customers are less important to the firm's future than the 20% of larger customers; hence, they should receive less attention and resources. For many managers, this is a harsh truth to stomach, but they cannot escape the reality that resources are scarce. Unless they accept and act on this reality, they will be condemned to the fate of one well-known company. A senior sales manager famously said of this organization: ‘The problem we face is that senior management doesn't seem to understand the implications of the 80:20 rule; they want us to be fair to all of our customers. The result is quite predictable; we give the same lousy service to all our customers.’1

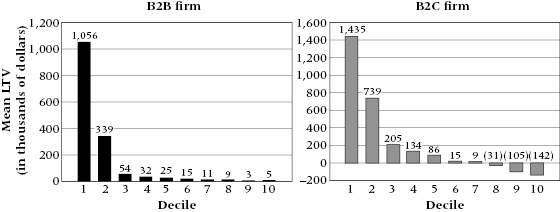

We can move beyond revenue distributions and even profit distributions to consider customer lifetime value (CLV) (Capon 2012). CLV is the expected discounted profit stream the firm earns from a customer factored by the retention rate/probability. Figure 2 shows empirical results from two firms: a B2C firm and a B2B firm (Kumar and Shah 2009). The y-axis measures CLV; the x-axis classifies firms by deciles – largest 10%, second 10%, etc. The figure shows that for both firms, the CLV distribution is highly skewed (in excess of 90:10); the top two customer deciles are responsible for CLV for each firm. For the B2B firm, CLV just declines as customer deciles become smaller. For the B2C firm, the eighth, ninth and tenth customer deciles incur losses.

Figure 2 Customer lifetime value distributions

To summarize: all firms have a relatively small number of customers (current and potential) that are critical for long-run future health. Because they are so important, the firm should treat them better than it treats its average customer. This admonition may sound unfair, but it is absolutely necessary. However, all firms have traditional organization structures and processes for addressing customers that may have been in place for many years but do not recognize the new reality. In this paper, we present these traditional systems, we discuss the various pressures they face, then we show the ways in which many firms are evolving their go-to-market approaches. These new systems recognize the realities of the fundamental business model and the Pareto distribution that characterizes their revenue sources, and attempt to address their weaknesses in this new and evolving world.

Addressing customers

Most B2B firms' traditional approach to addressing customers typically embraces some form of personal selling effort. The basic choice that firms make is to conduct this activity in-house with an employee sales force or by outsourcing the selling effort to third parties such as agents, brokers, representatives and/or distributors. When the firm decides to conduct the selling effort itself, it must trade off selling effort effectiveness with the cost of sales. Typically, the least costly approach is to organize the sales force by geography – each salesperson sells all of the firm's products to all customers within a well-defined geographic area. However, if customer needs and/or product characteristics vary widely, this approach may not be very effective. For this reason, the firm may specialize its sales effort organizationally by product, market segment, distribution level, current versus potential customers, or some other dimension. Indeed, a large firm may employ multiple types of sales specialization.

The crucial point is that all firms have some traditional sales organization in place. Certainly the organization evolves over time, but historically, firms have not considered customer importance as a key dimension on which to organize. To put it bluntly, the implications of the fundamental business model and the Pareto revenue distribution discussed above have not deeply penetrated many executive suites. But this is changing and in the next section we suggest some critical pressures that are causing firms to think more deeply about their go-to-market strategies and to make significant changes.

Generalized pressures on traditional go-to-market strategies

Regardless of the historic success of the particular go-to-market model the firm currently employs, four general areas – increased competition, environmental forces, globalization and sales force costs – are generating increased pressure on the firm.

Increased competition

There is scarcely any executive today who will tell you that the competitive environment is easing – virtually all will agree that competitive pressures are increasing in depth and scope. The best approach to competitive pressures is to adapt Porter's five forces model (Porter 1980) and consider each of the forces he identified as a competitor (current or potential). In this framework the firm faces five types of competitors:

As a general statement, the overall level of competition faced by most firms is increasing. Different firms face different competitor types and pressures. At any point in time, one competitor or another type may be more significant for the firm. Of course, all firms must consider not only the types and levels of competition they face today but also the potential competitors they may face tomorrow.

PESTLE forces

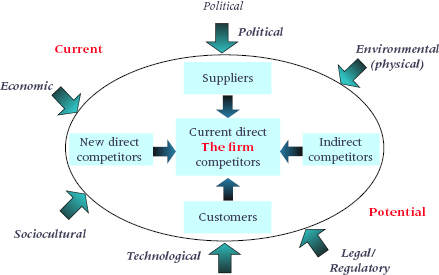

The firm must address a set of environmental forces that seem ever more complex and subject to change. The PESTLE acronym captures these well: P – political, E – economic, S – sociocultural, T – technological, L – legal/regulatory and E – environmental (physical environment).

Whether it is governmental policy changes, shifting social mores, the impact of the Internet, reregulation and deregulation, or global warming or the fallout from volcanoes in Iceland and Chile, the perturbations caused by PESTLE forces are seriously affecting most firms. Some forces impact the firm directly but, as Figure 3 illustrates, they also have an indirect impact via the firm's competitive environment.

Figure 3 Competitive and PESTLE pressures

Globalization

A special feature of broad environmental pressures is the seemingly inexorable march towards greater globalization (Friedman 2007). Factors driving increased globalization include a generalized political belief that trade is good; development of organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) to effect increased trade by reducing barriers; the maturing of economic and political unions (like the European Union (EU)) and free trade areas (like NAFTA); greater competitive home-market pressures that encourage firms to venture abroad; opportunities in emerging markets such as BRICI (Brazil, Russia, India, China, Indonesia); improved global communications and the Internet; and improved global transportation – by air for small packages, by sea via containerization, or by widening the Panama Canal.

The combined effect of these factors means that firms conduct increasing amounts of business outside their home-market boundaries. Increased globalization portends major implications for addressing the firm's customers.

Increased selling costs

Most observers believe that corporate expenditures on selling exceed higher-profile advertising and sales promotion, despite the impact of the Internet and customer relationship management (CRM) (Piercy and Lane 2011). For example, rough estimates suggest a 60:40 ratio in Great Britain (Doyle 2002). Until a few years ago, the now defunct Sales and Marketing Management annually published survey results on the cost of a sales call. This metric is simply the total cost of the firm's selling effort (including the entire support structure) divided by the number of sales calls. Year after year, this metric increased at a rate greater than inflation – more than doubling during the 1990s (Capon 2001).

Sales and Marketing Management may have perished but leading firms continue to struggle with this issue by making sure they place on-the-road sales effort only on those customers most likely to yield a positive return. Indeed, optimizing resource allocation to various types of selling effort is often a central concern to sales operations departments (Capon and Tubridy 2010).

Summary

All firms face these generalized environmental pressures. Indeed, these pressures have led to major changes in the economies of many countries and the nature of business organizations. The conglomerates of yesteryear have largely disappeared from Western economies as firms have focused their efforts on a restricted set of technologies. Company missions are more narrowly defined and firms increasingly spend resources on those activities where they gain differential advantage. Correspondingly, they prefer to outsource many support processes to specialist organizations. These pressures also impact the way companies address their customers, but we defer that discussion until we have examined a second set of pressures on the firm: those brought by the firm's customers.

Pressures from customers

A major form of economic structure to which many industries evolve is oligopoly. In oligopoly, a small number of firms – maybe just three or four – are responsible for most market share; typically a few smaller firms focus on narrow market segments. A generation ago, in industry after industry, in country after country, many domestic oligopolies flourished (Sheth and Sisodia 2002). To a very large extent, those economic arrangements are a thing of the past, largely as a result of globalization pressures, including cross-border mergers and acquisitions.

In many industries today, it is not a matter of a few firms competing in an industry country by country; rather, it is just a few firms competing globally. Quite simply, we are moving from an economy of multiple domestic oligopolies to a structure of global oligopolies. Consider some examples. The manufacturing industry of passenger jet aircraft that seat over 100 passengers comprises just two firms – Boeing and Airbus. In automobile tyres, three suppliers account for upwards of 60% of global market share – Bridgestone (Japan), Goodyear (USA) and Michelin (France). Add Continental (Germany) and Pirelli (Italy) and market share reaches close to 80%. Perhaps these two industries represent the extreme, but many other industries are moving inexorably in this direction.

Such concentration of economic power has critical implications for suppliers to these industries. The number of potential customers is fast reducing. Suppliers for large passenger jet aircraft have only two potential customers; suppliers to the automotive tyre industry have only a handful. In addition to customer pressure brought on by these external factors, many customer firms are increasing the pressure on suppliers by affirmatively reducing their supplier bases.

Affirmative reduction in number of suppliers

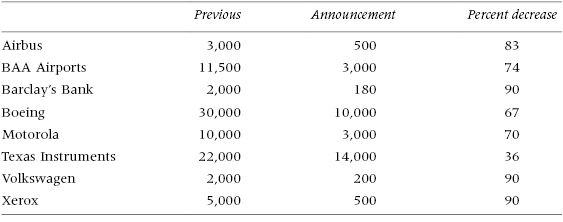

Many firms are deciding that they want fewer suppliers. Table 1 shows a selection of announced supplier reductions by well-known companies, collected over several years. In some cases, supplier base reductions reach 90%.

Table 1: Announced supplier reductions

Several reasons are driving these supplier reductions. First and foremost, customer firms believe a smaller supplier base can help them reduce input costs. Essentially, these firms believe that the traditional purchasing model of many competing suppliers is neither effective nor efficient. Rather, these firms believe that concentrating purchases among fewer suppliers allows these firms to secure economies of scale that will be passed on in the form of lower prices. In addition, fewer suppliers should lead to improved input quality. No matter how effective the firm's quality system, output quality is only as good as input quality. Fewer input sources tighten the quality distribution. Furthermore, the firm can send its own engineers to help a limited number of suppliers meet its requirements; such resource allocation would be prohibitively expensive for a large supplier base. Relatedly, the firm should receive more consistent service in multiple geographies and generally build closer relationships with suppliers.

Closer relationships between customer and supplier should lead to better communications, strategic pricing, greater transparency into supplier operations, improved operational excellence and enhanced input into supplier activities. Perhaps, even, the supplier–customer relationship could potentially evolve into true partnerships. When partnerships are successful, customer and supplier work together to evolve value further down the value chain.

Rising importance of procurement

A generation ago, purchasing was frequently seen as a managerial backwater. For rising executives, the purchasing department was often a way station where they put in two or three years as part of a learning tour of firm functions, on their way to more attractive and more senior managerial positions. Although firms had functioning purchasing departments, many firms did not build up significant intellectual capital in procurement.2

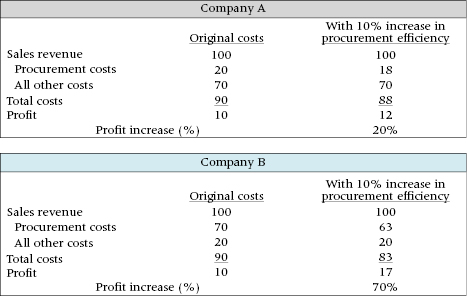

This situation is changing rapidly. Procurement (rebranded purchasing) is becoming a strategic issue for many firms, as we demonstrate using Figure 4. This figure shows simple income statements for two firms, Firm A and Firm B. In each case, revenues are 100, total costs are 90 and profit is 10. The only difference is in the levels of two different types of cost. For Firm A, total costs of 90 are divided between procurement costs – 20 and all other costs – 70. For Firm B, the cost levels are reversed: procurement costs – 70, all other costs – 20. Firm A is perhaps a vertically integrated organization that incurs most costs in-house; by contrast, Firm B is more of an assembly operation of purchased parts.

Figure 4 The rising importance of procurement

Setting aside issues of revenue generation, the core question is: where should the CEO of each firm spend their time? The answer is very clear. At Firm A, the CEO should focus on internal operations; these costs are 70, and a modest effectiveness gain would increase profits substantially. By contrast, a 10% effectiveness gain in procurement would reduce costs by only 2 and increase profits by 20%. The situation at Firm B is very different. The vast majority of Firm B's costs – 70 – are in procurement. A 10% cost reduction lowers costs by 7 and profits increase by 70%.

In firm after firm, in industry after industry, firms are shifting their operations from type A to type B. Earlier in this paper we discussed corporate evolution to more focused missions and then identified those activities that lead to securing differential advantage. All other activities are candidates for outsourcing. In many cases, the firm gains return on investment (ROI) benefits, in part by reducing the ‘I’ – offloading investment to the outsourced supplier. Additionally, the outsourced activity, such as a data centre, may operate more effectively because of the outsourced supplier's greater experience in that particular area.

An important factor driving outsourcing is the rising importance of branding. Not so long ago, customers generally believed that the firm whose name was on the product was also responsible for producing the product. That is no longer the case. The prime contemporary example is consumer electronics where Apple, for example, is highly successful. Apple does not manufacture the iPhone or the iPad; rather, Foxconn (Shenzhen, China) produces these products for Apple. Apple has figured out that manufacturing is not critical to securing differential advantage, so it outsources this process (but has significant competence in logistics and supply chain management). By contrast, Apple focuses on design innovation and its more recently developed competence in retail operations.

The shift from type A firms to type B firms heightens the importance of procurement. Procurement is becoming a strategic function for many firms. Budgets are larger, executive quality is higher, and in general the intellectual capital residing in procurement is increasing dramatically. Such changes imply that the selling job must change also. To address high-quality professional procurement executives, the firm must develop very different approaches than the traditional way of doing business.

Changes in the procurement process

Along with the increased importance of procurement and the increased professionalism of their procurement staffs, many firms have made significant changes in their procurement processes.

- Strategic sourcing. A decade or so ago this term did not exist. Strategic sourcing refers to the set of approaches, procedures and tools that organizational customers use to reduce their procurement costs. Consulting firms teach these processes and the movement of skilled procurement executives among companies has led to their widespread, and typically successful, adoption.

- Centralization. One of the fundamental managerial challenges today is to decide which functions and activities the firm should centralize and which should be decentralized. In many cases, firms are discovering they can be more effective by centralizing elements of procurement. Several reasons drive purchasers in this direction. First, greater concentration of intellectual capital is likely to spawn more ideas for reducing procurement costs. Second, aggregating purchases of similar products generally leads to larger contracts at better prices. Third, centralized procurement increases the likelihood that the firm can form supplier–customer partnerships to the benefit of both parties.

- Globalization. Earlier in this paper we discussed globalization as an important force affecting corporations. As an extension of increasing centralization, many procurement organizations are centralizing globally, entering into global contracts, and procuring certain goods and services on a global basis.

- B2B exchanges. Along with the growth of the Internet, many firms are using B2B exchanges to conduct reverse auctions for those goods and services that lend themselves to rigorous definition. When purchasing criteria are very clear, competing suppliers frequently drive down prices to attractive levels for purchasers (if not for suppliers).

- Insistence on interface simplification. Many companies now understand that the process of purchasing products and services can be very expensive. Furthermore, dealing with multiple salespeople and other executives from a single supplier can be administratively complex and slow down decision-making. Customers also want a single point of contact so they can secure fast and effective responses when critical issues arise. Hence, many customer firms insist on streamlining the inter-organizational interface, often by requiring that a single supplier executive has overall responsibility for the relationship.

- Broader scope of responsibilities. Historically, in many firms, purchasing was confined to quite specific areas, such as supplies or factory inputs. In firms where the procurement organization has successfully reduced spend in these areas, it often secures responsibility for other non-traditional areas of purchasing responsibility such as travel and consulting services.

So, in addition to facing complex competitive and PESTLE pressures, the firm must address pressures from customers. The critical issue for suppliers is deciding how to react to all of these external pressures and customer demands. If the customer requires a single point of contact globally, the firm had better make the appropriate changes or a competitor will emerge to satisfy this specific requirement and the firm may lose a customer.

But there is another perspective: perhaps the supplier can get ahead of the game. Rather than wait to react to customer demands, the firm may put in place the strategy, organization, processes and procedures, and human resources to provide customers with the sort of value that they will require in the future. By offering approaches that address the real problems their customers may face, the supplier may be able to secure significant differential advantage.

Impact of pressures on the firm

The position we take in this paper is that firms have a traditional go-to-market approach. This approach is either indirect through third parties such as agents, brokers, representatives and/or distributors, or direct via an on-the-road sales force. For many firms, this traditional system is under pressure from a series of competitive, PESTLE and customer pressures. As a result, the traditional system is fragmenting. We expect the traditional system to continue and evolve, but the various pressures are leading to two other systems developing. Rather than operate with a single traditional approach to the market, firms will increasingly add two new systems, making three systems in total. We characterize the two new systems as small account management and key, strategic and global account management.

Small account management

The skewed revenue and profit distributions that most firms experience are perhaps the major drivers for seeking alternative ways of dealing with small customers. Low revenues but high costs of traditional on-the-road approaches lead many firms to seek less costly ways of serving these customers. Broadly speaking, the firm has two types of alternatives – selling options and non-selling options:

- Part-time sales force. In general, part-time, on-the-road salespeople are less expensive than full timers. By careful territory design and astute salesperson selection, the firm may secure good customer coverage yet manage costs effectively. Pharmaceutical firms sometimes use this approach for covering retail pharmacies.

- Shift to telesales. Telesales can be very effective and is much less costly than on-the-road salespeople; a telesales operation may even be more effective than traditional salespeople. In Scandinavia, Reebok replaced a sales force calling on small stores with telesales. Customers got to know their salespeople, who were always available on the telephone. Customer satisfaction increased and costs decreased. Nirvana!

- Outsource selling effort: assign to agents/distributors. Frequently, product firms with sales force organizations operate with much higher levels of selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses than distribution firms and sales agencies. Furthermore, distribution and agency firms typically earn variable commissions, whereas producing firms typically carry a substantial level of fixed costs. As a result, distribution and agency firms can be profitable with customers and volume levels where producing firms cannot.

- Traditional direct marketing. The firm decides to address customers via various forms of direct marketing such as direct mail and other impersonal approaches. Profit margins increase and costs decrease.

- Electronic contact. The firm takes advantage of developing digital methods of communicating with customers such as email and websites. The firm may even combine websites with telesales and/or instant messaging. These approaches are far less costly.

- Raise prices. Thus far, we have discussed options for addressing the customer profit problem by reducing costs. A viable alternative may be to focus on enhancing revenues. Of course, the firm may lose some customers by raising prices, but customers that remain will be more profitable. Indeed, the firm may discover that its prices have been set too low.

- Stop serving. Raising prices is a soft way of losing customers; affirmative decisions to stop serving customers are much tougher. The firm sets performance levels on criteria such as sales units or revenues for a customer to remain a customer and then actively enforces the new rules. Strict implementation of well-chosen criteria will raise profits by ridding the firm of unprofitable customers. Relatedly, some customers may adapt their behaviour to remain customers and hence become profitable for the firm.

Key, strategic and global account management

Figuring out how to address small unprofitable customers is important for firms, but the major implication of the pressures we have discussed concerns what we may label as the firm's strategic (or key) and global account problem.3 Some executives have a difficult time defining a strategic (or key) account; we take a simple-minded view: a strategic (or key) account is any current or potential customer for which it would be a big deal for the firm to lose or to gain. This is not a terribly precise definition, but in our experience with many companies, we find that executives have a pretty good general idea of which these customers are.

This definition has an important implication – strategic (or key) is not synonymous with large. Certainly, many of the firm's strategic (or key) accounts are those customers that bring significant revenues today. But equally, some of today's large customers may not be strategic for the firm – perhaps they are declining organizations; perhaps they operate in areas that are no longer strategic for the firm; or perhaps revenues are high but profits are low. Conversely, some of today's small customers may be strategic for the firm because of potential revenues and/or strategic alignment. Remember, if the firm works closely with a small firm, forms a tight relationship, and the small firm is successful and grows substantially, the supplier's revenues will increase along with those of its customer. The supplier simply has to hang on for the ride.

Typically, the firm must take this general definition and work hard to identify the precise set of customers it wants to enter into its strategic (or key) account programme. The core reason is resources. Because they are strategic for the firm, these customers receive additional resources. But the firm can make two potential errors in its nomination and selection process: type A and type B. By making the type A error, the firm enters a customer into its strategic (or key) account programme that it should not have chosen: the firm does not earn an appropriate return on its invested resources – these resources are wasted. The type B error is more subtle but no less important: the firm fails to enter into its strategic (or key) account programme a customer that it should have chosen. Hence, it makes an opportunity loss.

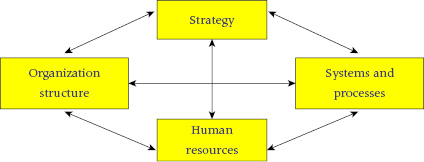

To develop an effective strategic (or key) account programme, the firm should make serious decisions about four building blocks, fundamental elements in the congruence model – see Figure 5.

Figure 5 The congruence model

- Hard infrastructure. Items in this category include synchronous information such as real-time communication, and asynchronous information like data storage and retrieval. Other critical areas are financial management systems such as customer profitability measurement, assessing customers' economic value to the firm, and strategic account planning systems.

- Soft infrastructure. These items include developing proposals, pricing and contracts, managing opportunities, addressing complaints, and suggestions.

- Improvement processes. These items combine hard and soft elements but are focused on improving the firm's approach to managing strategic (or key) accounts. They include monitoring and control systems, customer satisfaction measurement, best-in-class benchmarking, and best-practice sharing. This category includes meetings such as customer councils and forums, and business opportunity workshops.

Conclusion

In this paper we have attempted to make the case for managing strategic accounts. We have shown that the traditional sales force model is facing several types of pressure – from competitors, PESTLE forces, globalization and increased selling costs, and from customers. This combined set of pressures is leading to fragmentation of the traditional system. This system will remain, but two additional systems are forming – for small customers and for key, strategic and global customers. To develop a successful and comprehensive strategic (or key) account management programme, the firm must implement the congruence model. The firm must make critical decisions about strategy, organization structure, human resources, and systems and processes.

Notes

1 Personal communication to the first author.

2 See the Merck case in Noel Capon and Christoph Senn, Case Studies in Managing Key, Strategic, and Global Customers, Bronxville, NY: Wessex, 2011.

3 Note that key or strategic accounts may be global, but many such accounts are also domestic or regional in scope.