A configurational approach to strategic account management effectiveness

Abstract

At the turn of the millennium, most firms struggled with the challenge of managing their strategic accounts. Adopting a configurational perspective on organizational research, this paper reports the empirical state of SAM implementations at the time. Eight prototypical SAM approaches are described based on a cross-industry, cross-national study. The results show significant performance differences between the approaches. The prototypes are based on an integrative conceptualization of SAM that defines key constructs in four areas: (1) activities, (2) actors, (3) resources, (4) approach formalization. Finally, the paper reports findings on the effectiveness of SAM approaches. Internal culture matters a great deal while the formalization of the SAM approach does not. Overall, the study shows that companies should proactively manage their strategic accounts.

Introduction

This paper summarizes the findings of empirical research that was conducted in 1999 and published in two articles. One article, Homburg et al. (2002), focused on configurations of strategic account management. The other, Workman et al. (2003), focused on determinants of strategic account management effectiveness. At the time, the research project was the largest – and still is among the largest – empirical study on strategic account management ever done. In this paper, the summary of the two articles offers a description of the state of strategic account management at the turn of the millennium. Beyond the historical documentation, the research findings on SAM effectiveness are as provocative and challenging to managers and academics as they were at the time of their original publication.

The challenges in SAM have changed through the years as SAM matured as an instrument. We observe that much of the SAM-related debate today revolves around processes. At the time when we conceived our study, none of the expert interviews strongly emphasized this view. The professionalization of selling processes and the widespread adoption of selling process methodologies like Miller-Heiman, Solution Selling, and Target Account Selling, took place in the decade after we conducted our research. At the time of our research, the challenges resided more in the area of organizational structures (Whom should we appoint as account managers? To whom should they report?) and authority (How do we get local sales entities to cooperate with the account managers?). While the organizational structures seem to have moved out of focus, the authority challenge appears to us as an evergreen of SAM. This is where our research results are as current as ever.

In the business arena, at the turn of the millennium, many companies were faced with powerful and more demanding customers. These powerful buyers had in many industries been shaped through corporate mergers, typically in industry sectors such as retailing, automotive, computers and pharmaceuticals. These large customers often rationalized their supply base to cooperate more closely with a limited number of preferred suppliers (e.g. Dorsch et al. 1998; Stump 1995). They demanded special value-adding activities from their suppliers, such as joint product development, financing services or consulting services (Cardozo et al. 1992). Also, many buying firms centralized their procurement and expected a similarly coordinated selling approach from their suppliers. For example, global industrial customers demanded uniform pricing terms, logistics and service standards on a worldwide basis from their suppliers (Montgomery and Yip 2000). Internal organizational structures often hampered a coordinated account management, such as when the same customer was served by decentralized product divisions or by highly independent local sales operations. In addition, the complex set of activities for complex customers could not be handled by the sales function alone, but required participation from other functional groups. These developments had induced many suppliers to rethink how they manage their most important customers and how they design their internal organization in order to be responsive to these key customers. Firms increasingly organized around customers and shifted resources from product divisions or regional divisions to customer-focused business units (Homburg et al. 2000). This was when many firms established specialized key account managers and formed customer teams that were composed of people from sales, marketing, finance, logistics, quality and other functional groups (Millman 1996; Wotruba and Castleberry 1993).

In the academic literature just before the turn of the millennium, Millman (1996, p. 631) commented that ‘Key account management is under researched and its efficacy, therefore, is only partially understood.’ Kempeners and van der Hart (1999, p. 312) argued that ‘organizational structure is perhaps the most interesting and controversial part of account management’. In a qualitative study of marketing organization (Homburg et al. 2000), we had found the increasing emphasis on key account management (KAM) to be one of the most fundamental changes in organizations.

At the time of our research, while some research had focused on global accounts (Montgomery and Yip 2000; Yip and Madsen 1996), the term key account management (KAM hereafter) – rather than strategic account management – appeared to be the most accepted term in publications (Jolson 1997; McDonald et al. 1997; Pardo 1997; Sharma 1997) and the most widely used term in Europe. In our original research we used the words key account management and defined it as ‘the designation of special personnel and/or performance of special activities directed at an organization's most important customers' (Homburg et al. 2000, p. 463). This paper sticks to our original terminology. We subsume under key account management all approaches to managing the most important customers that have been discussed under such diverse terms as key account management, key account selling, national account management, national account selling, strategic account management, major account management or global account management. ‘National account management’ clearly has become a misnomer as business with important customers increasingly spanned country borders (Colletti and Tubridy 1987).

The paper is organized as follows. We begin with the results of the Homburg et al. (2002) article on configurations.

This is followed by an exploration of how the different approaches perform. We explore the outcomes of different KAM approaches and report the findings of the Workman et al. (2003) article on KAM effectiveness. We conclude by discussing implications of our research for theory and for managerial practice.

Given that taxonomies are less frequently developed than conceptual models, a few comments on their value are in order. As Hunt (1991, p. 176) has noted, classification schemata, such as typologies or taxonomies, ‘play fundamental roles in the development of a discipline since they are the primary means for organizing phenomena into classes or groups that are amenable to systematic investigation and theory development’. Given that the conceptual knowledge about the design of KAM is at an early stage and that our research endeavour is to expand its scope, a taxonomy is particularly useful in providing the field with new organization. By means of the taxonomy, we are studying the complex KAM phenomenon through holistic patterns of multiple variables rather than isolated variables and their bivariate relations. This research approach is consistent with the configurational perspective to organizational analysis that has been gaining increasing attention (Meyer et al. 1993). The basic premise of the configurational perspective is that ‘Organizational structures and management systems are best understood in terms of overall patterns rather than in terms of analyses of narrowly drawn sets of organizational properties' (Meyer et al. 1993, p. 1181). Thus, the configurational perspective complements the traditional contingency approach (Mahajan and Churchill 1990). Two alternatives of identifying configurations have been distinguished: typologies represent classifications based on a priori conceptual distinctions, while taxonomies are empirically derived groupings (Hunt 1991; Rich 1992; Sanchez 1993). Hunt (1991) notes that grouping phenomena through taxonomies as opposed to typologies requires substantially less a priori knowledge about which specific properties are likely to be powerful for classification, because taxonomical procedures are better equipped to handle large numbers of properties.

State of KAM literature at the turn of the millennium

Four main themes emerged from our review of literature on key account programmes. First, key account programmes encompass special (inter-organizational) activities for key accounts that are not offered to average accounts. These special activities pertain to such areas as pricing, products, services, distribution and information sharing (Cardozo et al. 1992; Montgomery and Yip 2000; Shapiro and Moriarty 1984b). Second, key account programmes frequently involve special (intra-organizational) actors who are dedicated to key accounts. These key account managers are typically responsible for a number of key accounts and report high in the organization (Colletti and Tubridy 1987; Dishman and Nitse 1998; Wotruba and Castleberry 1993). They may be placed in the supplier's headquarters, in the local sales organization of the key account's country, or even on the key account's facilities (Millman 1996; Yip and Madsen 1996). It is frequently stressed that key account managers need special compensation arrangements and skills, which has implications for their selection, training and career paths (Colletti and Tubridy 1987; Tice 1997). Third, key account management is a multi-functional effort involving, beside marketing and sales, functional groups such as manufacturing, R&D and finance (Shapiro and Moriarty 1984b). Fourth, the formation of key account programmes is influenced by characteristics of buyers and of the market environment, such as purchasing centralization, purchasing complexity, demand concentration and competitive intensity (Boles et al. 1999; Stevenson 1980).

We observed a number of shortcomings in prior research. First, the design issues above have mostly been studied in isolation and have not been consolidated into a coherent framework. Shapiro's and Moriarty's (1984a, p. 34) assessment that ‘the term national account management program is fraught with ambiguity’ was still valid. Second, there was a general lack of quantitative empirical studies on the design issues above, particularly on the cross-functional linkages of KAM. Where quantitative research had been undertaken, it had essentially been descriptive and has not systematically developed and validated measures. Third, much of the empirical work that had been done (and has driven conceptual ideas) was based on observations in large, Fortune 500 companies with sophisticated, formalized key account programmes. This excluded small and medium-sized companies that actively manage relationships with key accounts, but do not formalize the key account management approach. Quantitative empirical research had not taken up a comment by Shapiro and Moriarty (1984a, p. 5) in their early conceptual work that ‘the simplest structural option is no program at all’. Fourth, given that conceptual work had mentioned a variety of structural options (Shapiro and Moriarty 1984a), there was no broad-based empirical work that allows generalizations about how KAM is done in practice.

An integrative conceptualization of KAM

Approach to the conceptualization

In this section, we will blend the insights from prior literature into an integrative conceptualization of KAM. Our conceptualization is composed of fundamental dimensions of KAM, each of which comprises several key constructs. We will distinguish between two types of variables in developing our taxonomy. First, we will identify a parsimonious set of theory-based key constructs that serve as ‘active’ input variables for the cluster algorithm. Second, we will complement these with a number of ‘passive’, non-theoretical, descriptive variables which will be used to further characterize the clusters.

Fundamental dimensions of KAM

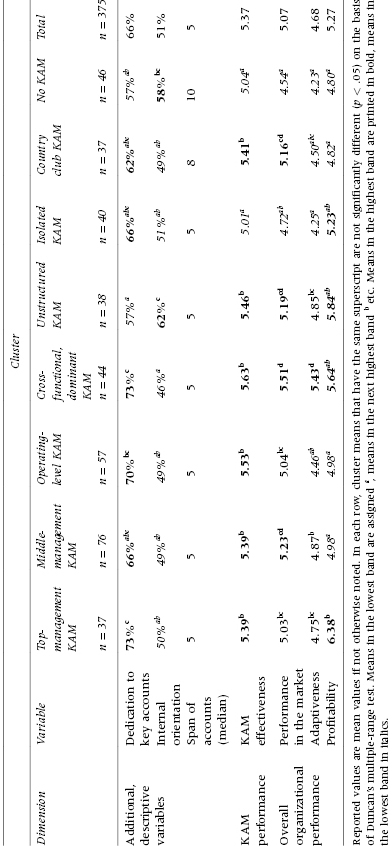

We begin our conceptualization of KAM by identifying the fundamental dimensions of the KAM phenomenon. Prior research on dimensions of KAM can be summarized in terms of three basic questions: (1) What is done? (2) Who does it? (3) With whom is it done? However, as we have elaborated in the literature review, the scope of prior research has been limited to formalized key account programmes with designated key account managers in place. We claim that to formalize or not to formalize the key account approach represents a decision dimension of its own. Therefore, we add a fourth question to KAM research: (4) How formalized is it? This leads us to conceptualize four dimensions of KAM. Drawing on research on the management of collaborative relationships that has distinguished between activities, actors and resources (Anderson et al. 1994; Narus and Anderson 1995), we refer to the four dimensions as (1) Activities (2) Actors (3) Resources and (4) Formalization. The first dimension refers to inter-organizational issues while the other three refer to intra-organizational issues in KAM. Figure 1 visualizes our conceptualization of KAM.

Figure 1 Conceptualization of key account management

Previous definitions of KAM have tended to focus on specific dimensions of KAM. Some authors focus on special activities for key accounts. As an example, Barrett (1986, p. 64) states that ‘National account management simply means targeting the largest and most important customers by providing them with special treatment in the areas of marketing, administration, and service.’ Others emphasize the dedication of special actors to key accounts. Yip and Madsen (1996, p. 24), for example, note that ‘National account management approaches include having one executive or team take overall responsibility for all aspects of a customer's business.’ Our conceptualization is more integrative because it encompasses both activities and actors, and additionally resources and formalization.

We will now go through each of the four fundamental dimensions of KAM to identify a parsimonious set of theoretically based key constructs. Those will be used as (active) input variables for the cluster algorithm leading up to the taxonomy. We will then identify additional descriptive (passive) variables that will help to enrich our descriptions of the clusters.

Activities

Both the KAM literature (e.g. Lambe and Spekman 1997; Montgomery and Yip 2000; Napolitano 1997; Shapiro and Moriarty 1984b) and the relationship marketing literature suggest inventories of activities that suppliers can do for their key accounts. Among these are special pricing, customization of products, provision of special services, customization of services, joint coordination of the workflow, information sharing as well as taking over business processes that the customers outsource. The first question that arises with respect to organizational activities is how intensely they should be pursued. Shapiro and Moriarty (1980, p. 5) argue: ‘A key issue here is: How will or does the servicing of national accounts differ from that of other accounts?’ Therefore, we define activity intensity as the extent to which the supplier does more for key accounts than for average accounts.

Beside the level of intensity on an activity, another important conceptual issue is the origin of that intensity. Given that powerful customers are often forcing their suppliers into special activities, the question arises whether the supplier or the key account proposes a special activity. Millman (1999, p. 2) observes that ‘some … programs are seller-initiated, some are buyer-initiated’. Empirical results by Sharma (1997) and by Montgomery and Yip (2000) indicate that supplier firms indeed use KAM in response to customer demand for it. According to Arnold et al. (1999, p. 15) ‘the proactive-reactive dimension matters a great deal’. Hence, we define activity proactiveness as the extent to which activities are initiated by the supplier.

Actors

Probably the most frequently discussed topic in key account programme research is which special actors participate in key account activities. These specialized actors can be viewed as a personal coordination mode in KAM. The participation of special actors has a horizontal and a vertical component. The KAM literature suggests that there are many possibilities for horizontally placing KAM actors, ranging from a line manager who devotes part of his time to managing key accounts to teams who are fully dedicated to key accounts (Shapiro and Moriarty 1984a). Similarly, Olson et al. (1995) present a range of coordination mechanisms with a permanent team at one end of their continuum. Marshall et al. (1999, p. 96) note ‘that team work is a fairly new concept in managing accounts and that salespeople are working in a team format much more today than in the past’. Cespedes et al. (1989) even argue that ‘selling is no longer an individual activity but rather a coordinated team effort’. It has been suggested the use of teams is a reaction to the use of purchasing teams on the buyer side (Hutt et al. 1985). We define the use of teams as the extent to which teams are formed to coordinate activities for key accounts.

While teams refer to the horizontal participation in KAM, another fundamental issue pertains to vertical participation. KAM actors may be placed at the headquarters, at the division level or at the regional level (Shapiro and Moriarty 1984a). The importance of senior executive involvement in KAM has frequently been underscored in the KAM literature. As Millman and Wilson (1999, p. 330) note: ‘Key account management is a strategic issue and the process should therefore be initiated and overseen by senior management.’ Napolitano (1997) points out that ‘top management must also play the lead role in securing business unit management support for the program.’ This is supported by writers on strategy implementation who argue that the organization is a reflection of its top managers (Hambrick and Mason 1984). Empirical support for the importance of top management has been provided by Jaworski and Kohli (1993) who have found market orientation to be positively related to top management emphasis on it. Therefore, we define top management involvement as the extent to which senior management participates in KAM. Hence, the top management involvement construct adopted from the literature on strategy implementation and on market orientation is conceptually close to the centralization construct used in organization theory, which refers to the extent of decision authority being concentrated on higher hierarchical levels.

Resources

As Shapiro and Moriarty (1984a, p. 2) have noted: ‘Much of the NAM concept as both a sales and a management technique revolves around the coordination of all elements involved in dealing with the customer.’ The KAM literature and the team selling literature have pointed out that support is needed for key account activities from such diverse functional groups as marketing and sales, logistics, manufacturing, IT, and finance and accounting (Moon and Armstrong 1994; Shapiro and Moriarty 1984b). ‘The key question, then, is: … how can a salesperson obtain needed resources?’ (Moon and Gupta 1997, p. 32). Obtaining resources has a pull and a push component.

In some cases, key account managers have special organizational power to ensure full cooperation from other organizational members. In other instances, key account managers have to rely on their informal powers and interpersonal skills (Spekman and Johnston 1986, p. 522). As the key account manager is typically part of the sales function (Shapiro and Moriarty 1984a), this lack of authority is most obvious for functional resources outside marketing and sales. We define access to non-marketing and sales resources as the extent to which a key account manager can obtain needed contributions to KAM from non-marketing and sales groups.

However, even within the marketing and sales function a key account manager may face difficulty in receiving support for his tasks (Homburg et al. 1999; Platzer 1984). One common problem is the lack of authority over regional sales executives who handle the local business with global key accounts (Arnold et al. 1999). For example, regional sales entities often resist company-wide agreements on prices or service standards. Therefore, we define access to marketing and sales resources as the extent to which a key account manager can obtain needed contributions to KAM from marketing and sales groups.

While access to resources refers to pulling on resources, research on team selling has frequently emphasized that the achievement of cross-functional integration in the selling centre is facilitated if the participating functions themselves push cooperation (Smith and Barclay 1993). Day (2000, p. 24) notes that in order to develop strong relationships with customers, ‘a relationship orientation must pervade the mind-sets, values, and norms of the organization’. Jaworski and Kohli (1993) refer to this concept of inter-departmental culture as esprit de corps. Culture is often viewed as a resource: ‘Organizational resources are the assets the firm possesses that arise from the organization itself, chief among these are the corporate culture and climate’ (Morgan and Hunt 1999, p. 284). Fisher et al. (1997) note that esprit de corps fosters the exchange of customer and market information. Therefore, we define the esprit de corps of the selling centre as the extent to which selling centre participants feel committed to common goals and to each other.

Formalization

As Shapiro and Moriarty (1984a) note, one of the ‘major organizational decisions that must be made as a company approaches a NAM program’ is: ‘Should there be a NAM program or no program?’ We believe that the distinction between more or less programmed approaches is highly relevant. As we have shown in our literature review, KAM approaches that do not have a key account programme in place are under-researched.

Characteristics of KAM programmes are the definition of reporting lines and formal linkages between departments, the establishment of formal expense budgets, the documentation of processes, and the development of formal guidelines on how to handle the accounts (Boles et al. 1994). Thus, in essence, the design decision of installing a key account programme revolves around the question to what extent KAM should be formalized. Consistent with writers on marketing organization (Olson et al. 1995; Workman et al. 1998), we define the formalization of a KAM approach as the extent to which the treatment of the most important customers is governed by formal rules and standard procedures. Hence, formalization can be viewed as an impersonal coordination mode, as opposed to top-management involvement and use of teams, which represent personal coordination modes in KAM.

Additional descriptive variables

In addition to the theoretical constructs developed above, the KAM literature also suggests a number of descriptive variables to characterize KAM approaches. These variables refer to very concrete, mostly demographic features of KAM approaches, such as the positions of key account managers. Because these variables are not theory based, we will not use them as input to the cluster procedure. However, given that these variables have frequently been discussed in KAM publications, we will use them to enrich our interpretation of different KAM approaches.

In many companies, KAM teams are led by a key account manager. We define the key account coordinator as the person who is mainly responsible for coordinating activities related to key accounts. The first descriptive variable refers to the position of the key account coordinators. One possibility is to establish dedicated full-time positions for the coordination of key accounts (Pegram 1972). A fundamental question in this context is whether key account coordinators are placed in the supplier's headquarters or locally in the country or geographic region of the key account's headquarters. An alternative to the full-time option is a part-time responsibility. As Shapiro and Moriarty (1984a, p. 5) note, ‘the task is often taken on by top-level managers … In other companies top marketing and sales managers and/or field sales managers take the responsibility.’

The second descriptive variable connects directly to this question of part-time vs. full-time responsibility. We define the key account coordinator's dedication to key accounts as the percentage of their time they spend with managing key accounts vs. average accounts. Another question concerning the allocation of time is how much time is spent with customers compared to the time devoted to internal coordination. Colletti and Tubridy (1987) report that 40% of a major account sales rep's time is administration work. We define the internal orientation of key account coordinators as the percentage of their time they spend with internal coordination vs. externally with customers. A final descriptive question that has frequently been raised in KAM studies is how many accounts key account coordinators are typically looking after (Dishman and Nitse 1998; Sengupta et al. 1997a; Wotruba and Castleberry 1993). We define the span of accounts as the number of accounts for which key account coordinators are responsible.

Outcomes

One of our objectives is to go beyond the conceptualization of KAM approaches and the taxonomy to explore the performance effects of design decisions. We distinguish between outcomes with respect to key accounts and outcomes on the level of the overall organization. Given that KAM involves investing in special activities and actors for key accounts which are not available for average accounts, we define KAM effectiveness as the extent to which an organization achieves better relationship outcomes for its key accounts than for its average accounts. While the benefits of KAM have often been claimed in the KAM literature, empirical evidence on the outcomes of KAM is rare and methodologically limited to t-tests or correlations of single item ratings of performance (Platzer 1984; Sengupta et al. 1997a; Stevenson 1981). A much better understanding of the outcomes of collaborative relationships has been developed by relationship marketing research (e.g. Kumar et al. 1995). This literature suggests that firms, through building relationships, pursue such outcomes as long-term orientation and continuity (e.g. Anderson and Weitz 1989; Ganesan 1994), commitment (e.g. Anderson and Weitz 1992; Geyskens et al. 1996; Gundlach et al. 1995), trust (e.g. Geyskens et al. 1998; Moorman et al. 1993; Rindfleisch 2000), and conflict reduction (e.g. Frazier et al. 1989).

Some authors indicate that KAM not only has outcomes with respect to key accounts, but also organization-level outcomes. As Cespedes (1993, p. 47) notes: ‘Another benefit is the impact on business planning. Salespeople at major accounts are often first in the organization to recognize emerging market problems and opportunities.’ Of course, organization-level outcomes are also affected by average accounts. Following the terminology of Rueckert et al. (1985), we distinguish between adaptiveness, effectiveness and efficiency. We define:

- Adaptiveness as the ability of the organization to change marketing activities to fit different market situations better than its competitors.

- Performance in the market as the extent to which the organization achieves better market outcomes than competitors.

- Profitability as the organization's average return on sales before taxes over the last three years.

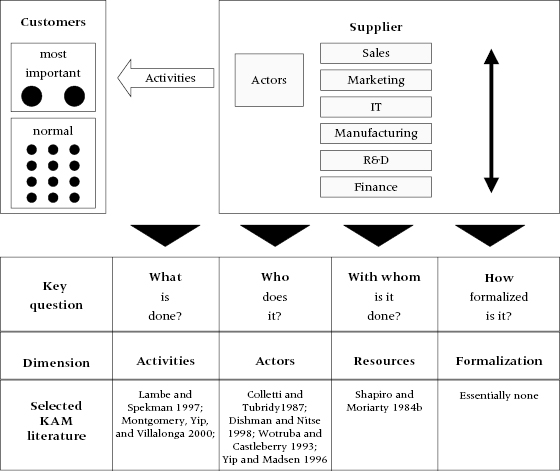

Sample

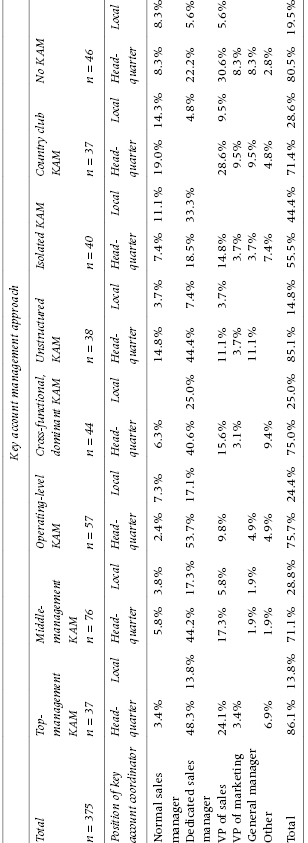

Given our research objective of identifying prototypical approaches to KAM, we collected data using a mail survey in five business-to-business sectors in the USA and Germany. Based on the field interviews, we determined that the most appropriate respondent is the head of the sales organization. As Table 1 shows, our respondents are high-level managers. We received responses from 264 German firms and 121 US firms for effective response rates of 31.8% and 14.6% and an overall response rate of 23.3%. Our measures are reported in the Appendix. The details of the measurement and clustering procedures are documented in the original articles.

Table 1: Sample composition

Key account management configurations

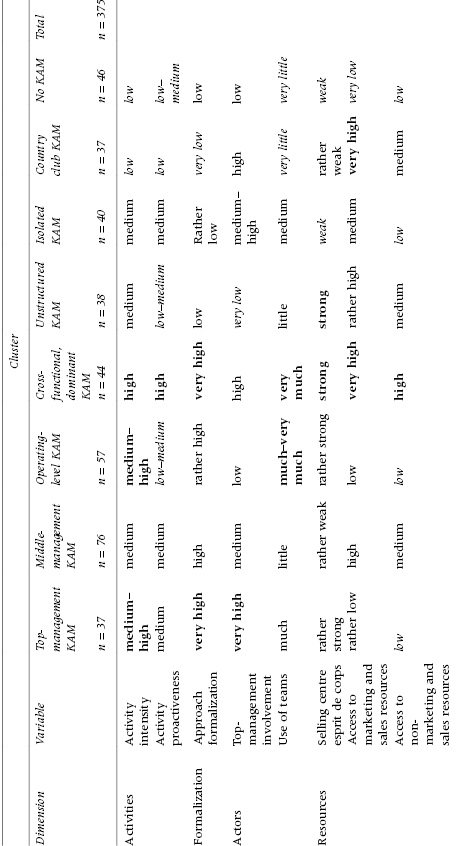

We will now interpret the clusters identified and will assign labels to the approaches (see Table 3). Although there are risks of oversimplification in using such labels, they serve the didactical purpose of highlighting empirically distinct aspects of different approaches and facilitate the discussion of the results.

Table 3: Position of key account coordinators

Top-management KAM

This approach truly deserves the name ‘programme’. These companies highly formalize the management of their key accounts. Over 60% of companies in this cluster have dedicated sales managers to coordinate activities for key accounts, which is consistent with the finding of 73% of key account coordinator time being devoted to key accounts. Top management manifests the highest degree of top management involvement in KAM. Hence, it is not surprising that this approach is managed out of the company headquarters (86.1% of key account coordinators are based in the suppliers’ headquarters). In addition to heavy top-management involvement, these companies make intensive use of teams. Activities for key accounts are intense and are proactively initiated. An interesting finding is that selling centre esprit de corps is high, whereas access to both marketing and sales and over non-marketing and sales resources is low. This may suggest that access to resources is barely needed. Top management might negotiate umbrella contracts, which are carried out by operative teams based on highly standardized procedures.

Middle-management KAM

This approach manifests a high level of formalization, but, in contrast to the first approach, top-management involvement is medium. Intensity and proactiveness with respect to activities are also on a medium level. These results may suggest that these companies have installed a formal key account programme, but on a middle-management level. Our interpretation is supported by the finding that 28.8% of key account coordinators are locally based in this approach, compared to 13.8% in Top-management KAM. The fact that key account managers are often locally based may also explain the high access to marketing and sales resources. On the contrary, selling centre esprit de corps and access to non-marketing and sales resources are low, which leads to the overall impression that KAM in these companies is mainly driven by (local) middle management in the marketing and sales function.

Operating-level KAM

These companies are doing a lot for their key accounts and have considerably standardized procedures. In these aspects, this approach is comparable to Top-management KAM and Middle-management KAM. However, top-management involvement is lower than in these other approaches. Not surprisingly, access to functional resources is low. While the VP of sales or marketing is the key account coordinator in 27.4% of Top-management KAM companies and 23.1% of Middle-management KAM companies, this is only the case for 9.8% of companies in this cluster. The low degree of top-management involvement together with fairly developed activities and teams may suggest that this KAM approach is mainly borne by the operating level. None of the other approaches has such a high percentage of companies with dedicated sales managers for key accounts (70.8%), 17.1% of which are locally based.

Cross-functional, dominant KAM

This cluster has the highest values for nearly all variables. First, activities are very intense and are proactively created. Second, formal procedures and team structures are fully developed. Top management is strongly involved. Third, selling centre esprit de corps and access to functional resources are high. 65.6% of Cross-functional KAM companies have dedicated sales managers as key account coordinators. Their share of time spent externally with the customer is the highest of all approaches, as reflected by the 46% on internal orientation. The overall picture suggests that these companies are completely focused on their key accounts. It seems that, in these companies, customer management is virtually identical with key account management.

Unstructured KAM

As shown by the low values on formalization, top-management involvement, and use of teams, these companies have not created special organizational structures for key accounts and do not have a programme in place. This is consistent with the observation that activities are more a reaction than a proactive initiative, as indicated by the 3.83 mean on proactiveness. KAM comes mainly out of the headquarters and key account coordinators are often normal sales managers (18.5% compared with 6.3% in Cross-functional KAM). An interesting observation is that 62% of key account coordinator time is spent on internal coordination, the highest percentage of all clusters. This may account for the fact that selling centre members have an extremely high esprit de corps for KAM and that it is no problem obtaining contributions from either marketing and sales or other functional resources. The overall impression is that these companies are pursuing KAM on an ad-hoc basis, mobilizing internal resources only when the key accounts ask for it. Interestingly, 11.1% of these companies name the general manager as the key account coordinator, although top-management involvement is the lowest of all approaches. This suggests that the general management's responsibility exists on paper only.

Isolated KAM

Intensity and proactiveness of activities as well as formalization and use of teams manifest mid-range values in this cluster. This seems to imply that these companies are trying to do something for key accounts, which is supported by the finding that top management is fairly involved. The most striking feature about this cluster is that in 44.4% of companies in this cluster, key account coordinators are locally based. This may explain why this cluster has very low values on selling centre esprit de corps and on access to non-marketing and sales resources. Hence, the overall picture is that KAM is a rather isolated, local sales effort in these companies which, despite some effort from the side of the top management, struggles for cooperation from the central business units.

Country club KAM

The striking characteristic of this cluster is a high degree of top-management involvement that goes along with low values on most other variables. The management of key accounts in these companies is not guided by formal procedures and teams are hardly ever formed. Special activities are performed less intensely and less proactively than under the other approaches. Most importantly, there are basically no dedicated key account coordinators. KAM coordinators are often the VP of sales, a general manager, even the VP of marketing. The comparatively low level of activities combined with high top-management involvement and high access to sales may suggest that, in these companies, KAM is little more than representation by senior managers. In 33.3% of these firms, key accounts are simply handled by normal sales managers. With the exception of the top-management involvement, this approach is fairly close to the ‘No KAM’ cluster.

No KAM

This cluster has the lowest values on nearly all variables: comparatively little activity is performed, but not proactively. Formalization is low, just as cross-functional cooperation and esprit de corps. It is interesting that mainly VPs of marketing and sales or general managers are named as key account coordinators, though top-management involvement in this cluster is low. This suggests that the VPs have responsibility on paper, but do not actually perform that role. The interpretation of this approach is straightforward: these companies do not manage their key accounts. Or some companies may only have started to manage their key accounts, given that they profess to have dedicated key account coordinators.

Key account management effectiveness

We now turn to the success of the various KAM approaches. In interpreting the results in Table 2, one has to pay attention to whether the outcome variable is on the level of the key accounts or on the level of the organization as a whole. KAM effectiveness can be assumed to be strongly influenced by how key accounts are managed and is thus our main outcome variable of interest. On the contrary, variance in organization-level outcomes, such as performance in the market, adaptiveness and profitability, can be explained by many factors other than KAM. In fact, a firm may be driving its performance, for better or worse, through the average as opposed to the key accounts.1

On both the KAM level and the organization level, the ‘No KAM’ and the ‘Isolated KAM’ approaches perform the worst. On the organization level outcomes, ‘Cross-functional KAM’ companies stand out with respect to both performance in the market and adaptiveness. As far as profitability is concerned, ‘Top-management KAM’ companies perform best. The fact that the most effective approaches are not the most profitable ones may be explained by the fact that some approaches, besides generating higher revenues, also involve higher costs.

A second observation in Table 2 is that several KAM approaches are equally successful. This finding is consistent with the concept of ‘equifinality’ emphasized by the configurational approach (Meyer et al. 1993). However, given our key informant design, it raises the issue of whether a common method bias is present in the data. Two facts from our data speak against the presence of a bias. First, a possible key informant bias should affect the subjective performance measures (e.g. KAM effectiveness), but not the objective performance measure (i.e. profitability). The fact that several configurations also manifest the same level of objective performance supports the validity of our findings on the subjective measures. Second, even in very active approaches (e.g. Top-management KAM), there is a lot of variance across the respondents concerning the performance variables. Indeed, the lack of significant differences between some approaches is due to the high variance rather than a tendency of all key informants to rate their own approach high.

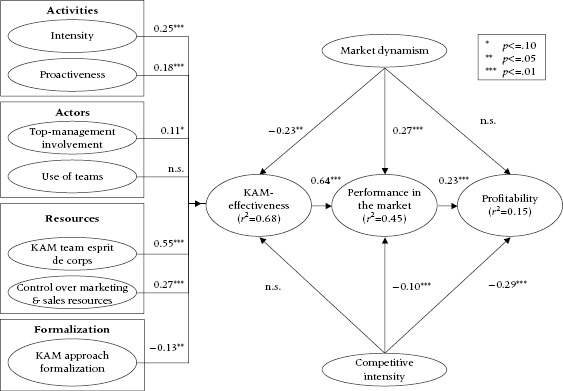

Figure 2 shows the results of a structural equation model on the performance relationships that is part of the Workman et al. (2003) article. We find that the dimensions of the KAM approach which positively affect KAM effectiveness (in decreasing order of effect) are KAM team esprit de corps, access to marketing and sales resources, activity intensity, activity proactiveness and top-management involvement in KAM. On the other hand, formalization of the KAM approach, a design parameter emphasized in the KAM literature, is negatively related to performance. The most surprising aspect of our findings is that the softer factors (e.g. top-management involvement, KAM team esprit de corps) matter more than formalization of the approach. One downside of formalizing the approach to key accounts is that this may lead to bureaucracy and impede flexibility in responding to the demands of different key accounts. To the extent that there is heterogeneity among key accounts, formalized approaches may get in the way of providing special treatment to customers.

Figure 2 Effectiveness of key account management (completely standardized coefficients)

One might argue that KAM effectiveness is especially important in the case when a large percentage of revenues come from key accounts. We analysed the potential moderating effect by a multiple group LISREL model. The sample was split by the median of the percentage of sales derived from key accounts. In the group with a high percentage of sales to key accounts, the effect of KAM effectiveness on performance in the market is stronger than in the group with low percentage of sales to key accounts. However, in both sub-groups, we observe strong and highly significant effects of KAM effectiveness on performance in the market (standardized effect of .40 in the case of low percentage of sales to key accounts and .55 in the case of high percentage). The significance of this moderating effect can be tested. In the first multiple group LISREL model, we freely estimated the parameters in both groups. In a second model, we introduce an identity restriction: we set the effect of KAM effectiveness to market performance equal in both models. If this restriction significantly deteriorates model fit (measured by chi-square), there is a significant moderating effect. As chi-square deteriorates by 4.3 (which is larger than the threshold value of 3.84), the moderating effect is significant at the 5% level. These findings are consistent with those of Birkinshaw et al. (2001) who find a significant difference in the effectiveness of global account structures for conditions of high vs. low dependence on global customers.

Discussion

Comparison of KAM configurations with existing research

While prior research has never classified KAM approaches empirically, there is some discussion of options companies have in implementing KAM. McDonald et al. (1997) suggest ideal types of KAM, assuming KAM approaches to line up along a continuum from pre-KAM to synergistic KAM (Millman and Wilson 1995a). Along the continuum, the activity intensity, use of teams and top-management involvement are implied to rise, which actually implies a correlation among these design variables. Our results do not support this ideal continuum nor the correlation. As we have shown, high degrees of top-management involvement occur in combination with both high and low degrees of activity intensity and in combination with both high and low degrees of use of teams.

A second typology of KAM programmes has been proposed by Shapiro and Moriarty (1984a) based on qualitative interviews in 19 large manufacturing and service companies (see also the supplementary comments by Kempeners and van der Hart 1999). These researchers distinguish between six types of KAM programmes which resemble the KAM approaches we identified. More specifically, their national account division resembles ‘Cross-functional KAM’, their corporate level programme is similar to ‘Top-management KAM’, their operating unit programme at group level is similar to ‘Middle-management KAM’, their operating unit programme at division level parallels ‘Operating-level KAM’, their part-time programme resembles the ‘Country club KAM’, and their no programme option is close to the ‘No KAM’ approach. However, our work goes beyond the prior work by identifying the design variables behind the approaches, by providing richer descriptions of the approaches, and by supplementing the descriptions with quantitative data. We also detected two additional KAM approaches, the ‘Unstructured KAM’ and the ‘Isolated KAM’. These two carry out a considerable amount of activity for key accounts while not formalizing the approach. In conclusion, our findings seem to indicate that we have not overlooked KAM approaches that occur in practice. This speaks for the validity of our taxonomy and for the absence of a non-response bias.

Research contribution to KAM configurations

Despite the immense importance of KAM in managerial practice, prior research in this area has been very fragmented and sound empirical studies have been scarce. Our contributions come from both the conceptualization and the taxonomy.

The first contribution is to provide conceptual clarity to KAM design decisions and to lay the basis for future research. Besides synthesizing the existing literature, this research extends the conceptual scope of KAM research by drawing attention to the fact that previous research has not gone beyond the boundaries of formalized KAM programmes to study non-formalized KAM approaches. We derive an integrative conceptualization of KAM identifying four key dimensions: (1) Activities (2) Actors (3) Resources and (4) Formalization (see Figure 1). We also develop scales for key constructs related to KAM.

A second contribution of our work consists in being the first study to empirically classify designs of organizational approaches to selling. While taxonomies exist for the buyer side (Bunn 1993) and for the relationship between buyer and seller (Cannon and Perreault 1999), there has been no taxonomy for the organization of the seller side. Moncrief (1986) has created a taxonomy of individual sales position designs, but the level of analysis in selling research has shifted to the selling team in the decade that followed (Weitz and Bradford 1999). As Marshall et al. (1999, p. 88) state: ‘Clearly, the operative set of sales activities representing a sales job in the mid-1980s is deficient to accurately understand and portray sales jobs of today.’ Hence, our taxonomy closes a gap in empirical knowledge about organizational approaches to selling.

A third contribution is the refinement of existing KAM typologies. We confirmed the types of KAM postulated by Shapiro and Moriarty (1984a), supplemented them with empirical detail and detected two additional approaches. These two carry out a considerable amount of activity for key accounts while not formalizing the approach.

An additional contribution of our taxonomical research is to provide deeper insights into the performance aspects of KAM approaches. On a general level, it is important to note that the same level of performance can be accomplished through different approaches. This is consistent with the concept of equifinality emphasized by the configurational approach (Meyer et al. 1993). Yet some approaches perform significantly worse than others. The finding that ‘No KAM’ companies are behind on all performance dimensions represents the most comprehensive empirical demonstration so far that suppliers benefit from managing their key accounts. The similarly mediocre performance of ‘Isolated KAM’ indicates that half-breed approaches to KAM are likely to fail. These results suggest that failure to achieve access to, and commitment of, cross-functional resources seems to play a critical role for the success of KAM programmes. This reinforces recent research on marketing organization that recognizes the cross-functional dispersion of marketing activities (Workman et al. 1998).

Research contributions to KAM effectiveness

One contribution is the identification of specific aspects of a KAM approach that lead to effectiveness. Prior KAM research has not been able to demonstrate which aspects of a KAM approach are most important. Our results indicate formalization of KAM programmes actually reduces KAM effectiveness. Having a formalized programme can impede flexibility and the ability to customize offerings to specific customers. Additionally, it may be more costly, due to administrative costs, or dedication of the best salespeople to these accounts when they might be more productively used elsewhere. Rather than a formalized programme, our results indicate the important factors are whether firms do different things for their key accounts, do them proactively, and then provide an overall culture and organization environment that provides the resources needed to support the KAM effort. Top-management involvement is important, not only for its direct effect on KAM success, but also for sending signals to the organization that support of the KAM effort is important. In terms of the categories of our model, activities and resources are more important than actors and formalization. Given the prior emphasis on KAM programmes and KAM managers (formalization and actors), our results indicate a shift in research direction towards better understanding the activities and resource dimensions that may be needed.

A second contribution is our finding concerning teams. It is not the extent of team use that affects KAM effectiveness, but rather the development of esprit de corps among those involved in the management of key accounts. The coordination of activities across the organization requires a common commitment to serving the needs of key accounts. Similar to the research on market orientation, our results indicate that development of an organizational culture that supports customers is a key driver of performance. Research on marketing's role within the organization has started to examine conditions which lead to marketing having relatively higher or lower levels of influence (Homburg et al. 1999) and the knowledge and skills necessary to connect customers with the firm's product and service capabilities (Moorman and Rust 1999).

While there is a long tradition of studying power and influence within the sales organization (e.g. Busch 1980) and within channels of distribution (e.g. Frazier 1983; Gaski 1984), there is a lack of research on cross-functional influence of the sales organization and competition for resources within the organization. Since KAM is primarily about managing and coordinating the activities of people over whom the key account manager does not have formal authority, additional research is needed to understand how key account managers can best accomplish their goals and obtain the needed resources. Research on product managers and new product development team leaders may be a good source of theoretical frameworks for addressing this issue of access to resources and ‘responsibility without authority’.

A third contribution is our finding that KAM effectiveness leads to profitability in the market. KAM effectiveness has a direct effect on performance in the market that then leads to profitability. Since performance in the market encompasses all accounts (not just key accounts), this result implies that there is a relationship between how well firms do with key accounts and their general performance in the market. This link between KAM performance and firm performance highlights the importance of the topic of KAM and the need for additional research on organizing to manage key accounts.

On a more general level, a fourth contribution of our research is that it highlights the importance of studying how firms manage their intra-organizational relationships. While there have been calls for field research that helps refine conceptualizations of buyer–seller relationships and the process by which these form and evolve (Narus and Anderson 1995), there has been relatively little examination of the intra-organizational processes involved. These relationships are complex due to the multiple people, products, functional groups, hierarchical levels and geographies represented on both buyer and seller sides. By identifying issues involved in the intra-organizational management of relationships, our study serves as a bridge between the relationship marketing literature and the marketing organization literature (e.g. Moorman and Rust 1999; Workman et al. 1998).

Managerial implications

One of the most fundamental managerial tasks is designing the internal organization. These design decisions are typically taken on the level of the organization rather than the level of individual accounts. Thus, the organizational perspective adopted in this research has particular appeal to top executives.

The key message to managers is not to take a ‘laissez-faire approach’ to KAM. Given that the ‘No KAM’ option is markedly less successful than other approaches, our results clearly call managers to actively manage key accounts. The fact that there are significant performance differences between the more actively managed approaches demonstrates that it is important to think consciously about how to design the approach in detail. Our work also shows that KAM requires support from the whole organization. Therefore, top managers should not leave the design of the KAM approach to the sales organization.

The conceptualization of KAM developed in our research provides managers with a systematic way to think through designing the KAM approach. As Day and Montgomery (1999, p. 12) note, ‘conceptual frameworks, typologies, and metaphors that are the precursors to actual theory building’ provide valuable guidelines for managers. Managers should work through four questions: (1) What should be done for key accounts? (2) Who should do it? (3) With whom is cooperation in the organization needed? (4) How formalized should the KAM approach be? We particularly emphasize that managing key accounts does not necessarily require setting up a formal key account programme.

The taxonomy developed further supports managers in designing their KAM. Managers can categorize their own company's approach based on the prototypical implementation forms identified. Based on the taxonomy, they can discover neglected design areas and develop alternative designs.

Specifically, managers involved with key accounts need to consider and debate the following questions:

- To what extent does your firm actually do different activities for your key accounts?

- Does your firm proactively initiate these activities?

- Is top management involved with KAM?

- Has your firm developed a culture that develops an esprit de corps among those involved in KAM?

- Do key account coordinators have sufficient access to marketing and sales resources?

Finally, our empirical results on effectiveness provide managers with guidance concerning factors having the greatest effect on KAM effectiveness.

- KAM team esprit de corps and access to marketing and sales resources by key account managers are particularly important. Because KAM is fundamentally about relating better to the firm's most important customers, changes are required throughout the organization and not simply in sales and marketing.

- Proactiveness has a significant effect on outcomes. Sales managers should not wait for customers to request special treatment, but rather should be proactive. In so doing, they can differentiate themselves from competitors and design KAM activities in a way that leverages their core competencies.

- Managers should involve the top managers in their firm in KAM. While prior research has claimed that top-management support is important (Napolitano 1997; Platzer 1984; Weitz and Bradford 1999), there has been lack of empirical support. Our data indicate a significant positive association between top-management involvement in KAM and success.

- Finally, managers should exercise caution in regard to formalization of KAM. Our results indicate a negative association between KAM formalization and KAM effectiveness. As emphasized above, the activities, actors and resources seem to matter more than formalization.

Conclusion

KAM continues to be a highly relevant issue for marketing and sales managers. In addition, it is still a highly interesting area for academic research. The research reported in this paper has provided the basis for future research through contributing an integrative conceptualization of KAM. It also filled a gap in knowledge about how firms actually design their approach to key accounts. Finally, it showed that actively managing key accounts leads to significantly better performance than neglecting them.

Appendix

Scale items for theoretical measures

| Construct | Items |

|---|---|

| Activity intensity (reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = not more than for average accounts and 7 = far more than for average) | Compared with average accounts, to what extent do you do MORE in these areas for key accounts?

|

| Activity proactiveness (formative scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = not more than for average changes and 7 = far more than for average) | Do the activities in these areas derive more from customer initiative or more from your own initiative? (items equivalent to activity intensity) |

| Top-management involvement (reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree) | Within our organization …

|

| Use of teams (reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree) | Within our organization …

|

| Selling centre esprit de corps (adapted from Jaworski and Kohli 1993; reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree: R = reverse scoring) | People involved in the management of a key account …

|

| Access to marketing and sales resources (reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = very difficult and 7 = very easy) | How easy is it for the key account coordinator to obtain needed contributions for key accounts from these groups?

|

| Access to non-marketing and sales resources (reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = very difficult and 7 = very easy) | How easy is it for the key account coordinator to obtain needed contributions for key accounts from these groups?

|

| Approach formalization (reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree) | Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.

|

| KAM effectiveness (reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = very poor, 4 = about the same, and 7 = excellent) | Compared with your average accounts, how does your organization perform with key accounts with respect to …

|

| Performance in the market (reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = very poor, 4 = about the same, and 7 = excellent) | Relative to your competitors, how has your organization, over the last three years, performed with respect to …

|

| Adaptiveness (reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = not more than for average accounts and 7 = far more than for average) | Relative to your competitors, how has your organization, over the last three years, performed with respect to …

|

| Profitability (interval item with 10 levels of variable provided) | What was your company's average pre-tax profit margin over the last three years? 1 = negative; 2 = 0–2%, 3 = 2–4%, 4 = 4–6%, 5 = 6–8%, 6 = 8–10%, 7 = 10–12%, 8 = 12–16%, 9 = 16–20%, 10 = more than 20% |

| Competitive intensity (adapted from Jaworski and Kohli 1993; reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree) | Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.

|

| Market dynamism (adapted from Jaworski and Kohli 1993; reflective scale, scored on 7-point scale with anchors 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree) | Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.

|

Notes

Reproduced with the kind permission of the American Marketing Association, parts of Homburg, C., Workman, J. and Jensen, O. (2002) A configurational approach on key account management. Journal of Marketing, April, 66.

1 We owe this idea to an anonymous reviewer.