Strategic account plans: their crucial role in strategic account management

Abstract

Strategic account plans sit at the core of KSAM: they specify the value to be offered to the customer and received by the supplier. They should be what gets done, and yet very little has been written about them. This paper discusses the essential elements of strategic account planning: the purpose of strategic account plans; their role in value creation; the importance of understanding and quantifying customer profitability; the key account manager's role in their development; and the plan production process, linked to corporate planning. Since these plans are highly confidential and rarely available for study, almost nothing has been documented on what they look like and what they contain, so their structure, format and content are described. With so much business at stake, plan quality needs to be excellent, but unfortunately quality is an issue, as is implementation. Finally, the information captured in these plans can quantify the value created by KSAM at the level of individual customers and the more aggregated levels of all customers and the whole company, although the equation is far from straightforward. Overall, strategic account plans play a critical but overlooked role in successful KSAM.

Introduction

A great many excellent and important ideas about key strategic account management (KSAM) programmes have been researched and discussed by many authors, particularly in terms of structure, selection of key customers, profitability, actors, and the core requirement of value creation for customers (Pardo 2006). Many good suppliers already give key customers plenty of attention, but they are often not clear about what tangible difference implementing KSAM makes to their approach to a key customer. We believe the problem lies in their failure to articulate, specify and plan for the value they need to create for these customers.

In the absence of tailored value created for the customer, KSAM will fail. As Piercy and Lane (2014) say, ‘A supplier's most important customers require dedicated resources and special value-adding activities. … If there were no such advantage for the buyer, then there would be no basis for a strategic account/strategic supplier relationship.’ We contend that, unless the value is defined and described in a plan dedicated to each key customer (and implemented, of course), there may not be any real value creation and that, even if a valuable concept has been developed, it is unlikely to be realized and delivered without a reasonably formal mechanism to inform and gain the commitment of the customer and the rest of the business. This puts key account plans at the very heart of successful KSAM, and yet very little has been written about them: this article seeks to begin to redress that balance.

Essential elements of KSAM planning

The key account plan should pull together all the knowledge and thinking around each customer to identify powerful and affordable value recipes for them. Without such a plan, it is impossible to begin to assess whether the customer will respond, and to what extent, and whether the response justifies the costs. The plan needs to address how the value ‘recipe’ will be converted into action, and that must be made sufficiently clear to all deliverers for them to understand what they need to do, and to gain their commitment to doing it. We contend the following:

- KSAM strategy will not be enacted unless aligned strategies are developed at the level of individual key accounts and made explicit in key account plans.

- Sustainable KSAM requires the creation of customized value for both parties, made explicit in key account plans.

- Customer profitability is best assessed, optimized, forecast and managed through the key account plan.

- The key account manager (and team) knows more about the account than any other supplier function and has responsibility for developing account strategies and plans.

- Account plans should have a consistent format to ease assessment, information sharing and business planning.

- Effective implementation of account plans requires approval by the organization, acceptance and support from the customer, adequate resource provision, aligned action and monitoring for plan progress, as well as results.

These principles are all concerned with the production, viability and implementation of each plan, and hence KSAM as a whole. While they are clearly interlinked, we will look at them separately in order to consider the scope and importance of each.

The purpose of strategies and plans for individual strategic and key accounts

KSAM is itself a corporate strategy at the highest level (ibid. Piercy and Lane 2014), but in order for KSAM to be realized, its precise meaning in each supplier requires further clarification. Many companies mistake their objective as their strategy in KSAM. They describe their aspiration in terms of growth in sales and/or profits from key customers, apparently failing to notice that simply stating a number does not achieve it. Until how they will achieve the desired outcome is specified, i.e. the strategy/ies, there is no defined route to success that people can enact.

KSAM strategies, even at a high level, can be very varied: they may focus on the introduction of new products; greater supply chain flexibility; extra capacity; new technology or services that will add value to key customers; and they may include initiatives that offer more efficiency or effectiveness for the supplier, such as production savings, joint marketing, or other strategies that may be both powerful and worthwhile when implemented for large customers, but not necessarily for the whole customer base. Certainly, vague assumptions about future activity are no substitute for explicit, customer-specific strategies. As Pardo et al. (2006) say, ‘Suppliers need to be clear about their specific value focus in the relationship in order to optimize activities, processes, and resource allocation.’ These authors identified several kinds of value, depending on which party creates and which consumes or appropriates the value (Biggart and Delbridge 2004):

- Exchange value, created through the supplier's KSAM activities and consumed or appropriated by the customer, e.g. tailored product offering.

- Proprietary (supplier) value, created and appropriated by the supplier (alternatively, proprietary customer value would be found where it is created and appropriated by the customer), e.g. supply chain efficiencies.

- Relational value, co-created value appropriated/consumed by both parties (Payne et al. 2008), e.g. joint new product development.

At a high level, a supplier's KSAM strategies may favour one or more of these values overall, although a strong focus on proprietary supplier value with limited attention to the other types of value is unlikely to appeal to customers, and therefore leads to unsuccessful KSAM. The emphasis and expression of the high-level strategy should be different in each customer.

Strategic account managers are often disappointed when their company rejects some of their ideas for customer strategies, and yet they have not articulated those ideas in a structured plan that allows the company to assess those ideas strategically, operationally and financially in a rational manner. The plan can be as important to the customer as it is to the key account manager and the supplier: as Pardo et al. (2006) say, ‘Customers that are key accounts should have an understanding of the value strategy that is pursued by the supplier in order to optimize their own position’. Through the account plan, both parties can see how their strategies can be aligned to optimize the benefits they gain from the relationship.

Godfrey (2006) placed the key account plan at the heart of KSAM when he identified four functions for the plan which address key actors in KSAM:

- For the customer, to make visible and explicit the added value they could expect.

- For the supplier, to show how the plan contributes to the corporate vision expressed in the corporate business plan.

- For the key account team, to specify and clarify strategies and objectives so they could understand what success was and know when they achieved it.

- For other key account managers, to share their plans and experiences for others to learn from them.

Additionally:

- For the key account manager, to provide a clear roadmap for management of the account and to gain the organization's approval and support for it.

Many companies pride themselves on being ‘action-orientated’ and do not genuinely value strategy. Indeed, according to Collis et al. (2008), 85% of American directors do not know what the components of a strategy are, with the result that organizations drift aimlessly until financial disaster strikes. That failing is manifested by a lack of KSAM strategy at the higher level, which translates into a lack of strategy at the customer level too. If good-quality strategic customer plans are not required by top management, key account managers see their production as a waste of time. In the absence of an explicit strategy captured in a plan, the key account manager falls back on day-to-day activity, which is perceived by the customer as traditional selling and normal customer service. Consequently, the customer just responds to the supplier's approaches in the same way as before, and not to the supplier's inflated expectations – while there may not be a plan, there is always an objective.

Planned value creation

Value is seen as the driver of the exchange process, and the fundamental basis for all marketing activities by Holbrook (1994), while Anderson (1995) considered value to be the reason for the collaborative relationships that Lambe and Spekman (1997) put at the heart of KSAM relationships. Sustainable KSAM should offer value for both supplier and customer (Pardo et al. 2006). We all acknowledge that in the last quarter of the 20th century commercial power moved from producers to customers, but many suppliers still operate a product- and production-orientated culture and keep customers at arm's-length. Vandermerwe (1999) goes as far as suggesting that traditional capitalism has become irrelevant and needs to be replaced by new business models based on ‘customer capitalism’.

Successful KSAM should balance the value appropriated by the supplier and customer, but it is often not so. Some suppliers making healthy profits from a big business with the customer give nothing special in exchange; and some customers have captured the lion's share of the value available in the current business model, leaving the supplier with a poor return on their investment in the customer. Neither of these situations is sustainable in the long term but, even so, the winning partner is often deaf to suggestions that the balance should be adjusted voluntarily before the loser takes drastic action, like switching to another supplier, demanding major price increases or even withdrawing supply. As Anderson and Narus (1999) point out, however, value does not exist in isolation, but is relative to competitive offers.

While value can be created through a variety of different strategies, in most cases it will finally be defined as a benefit feeding through to the bottom line, although suppliers are becoming increasingly involved in supporting their customers' ‘green’ reputation or social responsibility agenda. Cynics might suggest that these strategies are really aimed at profit sustainability anyway, and most value initiatives are directly linked to profit improvements. These will, broadly, stem from reducing costs or from business growth. Woodburn et al. (2004) concluded that:

- For customers, the bulk of value creation by suppliers results in lower costs.

- For suppliers, the bulk of value creation by customers results in business growth.

That is not to say that customers would not welcome suppliers who helped them raise their prices or grow volumes with their customers; or that suppliers would not be delighted if their customers enabled them to save costs and, indeed, such initiatives do occur. However, Kalwani and Narayandas (1995) also showed that customers were adept at bargaining away supplier cost savings. Generally, customers expect suppliers to cut costs for them (directly or indirectly) and are receptive to that approach, and suppliers expect to increase the volume of business they have with customers: therefore most effort seems to be directed towards these kinds of value creation.

Planning for customer profitability

Managing powerful customers profitably is perhaps the biggest issue facing suppliers today, as markets mature, particularly in Western Europe and America, and as inexpensive versions of goods which were hitherto only supplied by the West flood into their markets from lower-cost countries such as China. Most organizations respond by putting pressure on their suppliers because the easiest and quickest way to increase margins which are being challenged is to cut the price paid for external goods and services. The problem with this approach, however, is that price cutting is finite, whereas value creation is infinite and is limited only by creativity and imagination.

It seems self-evident that KSAM programmes should aim to acquire and retain customers that have the greatest potential for profit (Ryals 2005; Thomas et al. 2004) which assumes that the costs of acquiring and supporting these customers do not outweigh the benefits (Blattberg et al. 2001; Gupta et al. 2004). However, Woodburn and McDonald (2001) showed that even suppliers claiming to have a good idea of customer profitability (i.e. the profit the supplier makes from its business with the customer) only captured data in terms of product-based gross margins, while some of their customers were clearly ‘voracious consumers of resources’ (p. 86), which were not quantified and recorded.

Differences in buying power, strategy, structure, buying mix, sector and activities result in profitability varying widely between customers (Ryals 2005; Storbacka et al. 2000; Wilson 1999), so this lack of understanding of how much the supplier is actually making from each key customer is clearly dangerous. This degree of variation between customers implies that the issue should be addressed at the level of the individual account, not customers overall or even key customers as a group. Cooper and Kaplan (1991), Kalwani and Narayandas (1995), Wilson (1999) and others have shown that some of a supplier's largest customers had eroded supplier margins to such an extent that the business with them made a loss for the supplier. Furthermore, Van der Sande et al. (2001) found that Henkel's expectations of which customers were most profitable were wrong in many cases. Similarly, the key account manager of a leading financial services company's biggest customer found, having completed a special project to establish the actual profitability of this, his only customer, that his (and his company's) expectation was ‘100% wrong’. Such discoveries should constitute a ‘wake-up call’ for all suppliers.

The account plan is the most appropriate place to analyse, develop and manage a key customer financially. Bradford et al. (2001), Ryals (2005), Van Raaij et al. (2003) and many others have demonstrated how customer profitability affects strategies for and management of key customers, so logically they should be discussed and integrated within the same instrument. Just as strategies are meaningless without numbers, numbers are meaningless without strategies and explanations of what will be spent and why and what returns can be anticipated. A strategic key account plan should show the earnings from the customer in the past and in the future, assuming that the strategies described in the plan are implemented. In addition to the income, it needs to make visible the costs, both direct product/service/logistic costs, and indirect costs like marketing, project and relationship costs, including those of the key account manager and team. Furthermore, any investments which will deliver beyond the current financial year need to be included in an appropriate manner, e.g. expressed in discounted cash flow terms like any other investment. Indeed, rather than being presented with a single number, finance departments would prefer forecasts given as a range around the mean with a probability of achievement attached to it (Woodburn 2008).

Role of the key account manager in plan development

It seems self-evident that the key account manager is the prime mover and person responsible for developing and delivering the account plan, together with the account team. We have observed a distinctly higher quality in plans (wider-ranging, better informed and more strategic) developed in conjunction with a multi-functional account team, compared with those produced by key account managers working solo. Achieving a good-quality outcome requires considerable skills on the part of the key account manager (Woodburn 2006a): of leadership, inter-personal and political awareness, diplomacy and coaching; of competences like analysis, financial understanding, technical and product knowledge, and knowledge of their own company's capabilities; and of vision, strategy development, forecasting and the ability to communicate with clarity and impact in writing and in person. Not surprisingly, not all key account managers possess such a range of skills at a sufficiently high level.

To an extent, shortfalls in the key account manager's portfolio of competences and personal attributes can be compensated by team members, provided that the key account manager has the ability to gain their participation and commitment to the planning process, and capture the outputs in the plan. However, there is a minimum level of competency below which the key account manager's ability to understand the team's contributions, render them into a well-organized plan and represent it to others internally and externally would be compromised.

The literature on the competences of key account managers, e.g. Sengupta et al. (2000), Wotruba and Castleberry (1993), initially focused on selling as the principal requirement, although Wilson and Millman (2003) shifted the focus with their paper on the key account manager as ‘political entrepreneur’. The view of the key account manager's role changed, for some at least, towards a more managerial position. Holt (2003) noted that good global account managers spent 10% of their time on account planning and Woodburn (2006b) found suppliers from diverse sectors who agreed that 5–15% of time should be spent in this way, but believed that, in reality, it was next to zero in their companies. Otherwise, very little attention has been given specifically to the key account manager's role in successful account planning and the competences it demands. In this respect academia mirrors suppliers themselves, which generally do not emphasize planning competences in their recruitment and requirements of key account managers. However, if the key account plan is at the heart of KSAM (Godfrey 2006), the key account manager is at the heart of the planning process, and needs to apply the time and competences it deserves.

The strategic account manager will need project management competency to manage the planning process and coaching skills to support team members playing their part in it. In addition to developing the plan, the strategic account manager and team play a crucial role in presenting it, both internally to senior management and externally to the customer. While key account managers are commonly trained in presentation skills, strategic account team members often are not. We have seen many examples where the supplier's senior managers and the customer have found team presentations more productive than a solo performance by the key account manager (still the norm), but team members probably require extra training in communication and inter-personal skills to fulfil this valuable role.

The planning process

Little enough has been written about account plans as a whole, and virtually nothing about the planning process. The process generally takes weeks, even months, so it is necessary to map it out to ensure that steps are planned in advance and that those involved have set aside the time and resources to complete it to schedule. Shortcuts tend to be at the expense of involving the customer and the account team, which is a false economy if the process fails to engage the commitment of either. Plans written by key account managers on their own are usually limited in scope; often based on incomplete information; and tend to struggle to get buy-in from the rest of the company.

Customers may or may not wish to be part of the process. Refusing the supplier's invitation to participate is probably an indicator of a fairly distant relationship, not the kind of collaborative relationship sought in KSAM. These more distant relationships are limited in their short-/medium-term potential, so if the customer does not choose to contribute to the planning process, the supplier should recognize the business-limiting nature of their current position with that customer and plan accordingly.

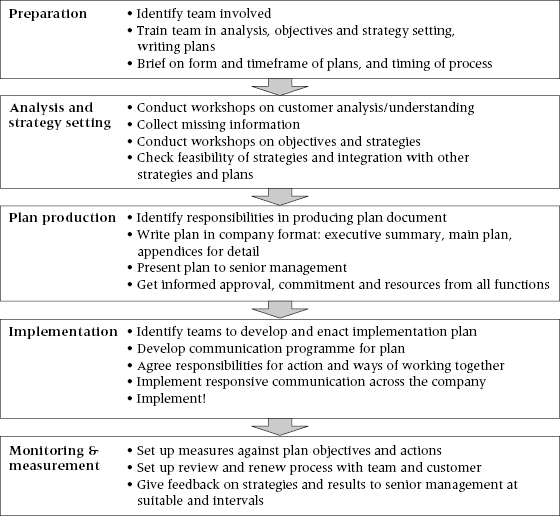

Consideration of the five stages of strategic account planning shown in Figure 1 demonstrates why the key account manager needs to dedicate a significant amount of time to it. They must expose the planning process and solicit the time of customers, team members and senior managers in order to secure their contribution. The plan should be ready in time to make an input to the supplier's overall business planning process (see pages 253–5).

Figure 1 The account planning process

The plans for strategic accounts together represent a substantial amount of business, and probably represent an increasing proportion of the business in the future. This increasing dependency is a risk to the supplier (Piercy and Lane 2014) that needs to be recognized, but the alternative, to limit or give up some of this business, may be even more risky. At least, the supplier should acknowledge the expectations of strategic customers, the strategies planned for them, and the business that is anticipated; and build those expectations and its response to them into its overall business plan.

In order to achieve that coordination, there needs to be a process whereby the individual account plans inform and feed into corporate planning. It should be backed by a process of iteration, in which the account plans bid for resource and demonstrate the return that can be expected for it; the company decides what it will and will not support; and the account plans are adjusted accordingly and resubmitted to the corporate planning process. In our experience, corporate planning and account planning operate independently, with the latter process ‘freewheeling’ within the sales function. The consequences are that the corporate plan sets customer performance targets which, unrelated to the account plans, may be quite nonsensical; and the company may miss out through not providing resources to fulfil productive strategies, and possibly failing to recognize critical market changes.

KSAM plans in the context of corporate planning

According to McDonald (2012), KSAM planning should take place before draft plans are prepared for a strategic business unit, or at least at the same time. As a general principle, planning should start in the market where the customers operate. Indeed, in anything other than small organizations, it is clearly absurd to think that any kind of meaningful planning can take place without the committed inputs from those who work with the customers, particularly key accounts. Yet many companies develop their business plans by a separate process run by Finance, without the inputs of customer managers, who are then on the receiving end of the outputs of the process, i.e. sales targets.

At the same time, individual customer strategies must be developed in the light of the supplier's corporate strategy, or they run the risk of depending on propositions that the supplier will never implement. This suggests another reason why customer strategies must be explicit and documented, i.e. to ensure that they are sufficiently aligned with corporate strategy. However, they need not passively comply with current corporate strategy, but should seek to influence future strategy to ensure the inclusion of key customer expectations and opportunities. So those aspirations need to be both visible and specific enough for the supplier to be able to evaluate them properly.

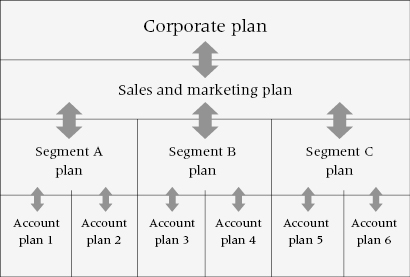

Kicking off the annual business planning round, key account strategic plans should represent messages from and responses to the marketplace, especially the most influential customers, i.e. key accounts, but also reflect the overall, longer-term corporate strategy. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between plans in the organization. It does not include the plans of other functions, like supply chain, research and development, customer service, etc., but since the fulfilment of key account strategies will often fall to them, those plans also need to be informed by the key account plans.

Figure 2 Hierarchy of strategic plans

Research into the efficacy of strategic plans for marketing and strategic accounts (McDonald 2012) has shown that such plans, when well conceived and executed, make a significant contribution to commercial success, the main effects being:

- The systematic identification of emerging opportunities and threats.

- Preparedness to meet change.

- The specification of sustainable competitive advantage.

- Improved communications between different functions and their managers.

- Reduction of conflicts between individuals and departments.

- The commitment of key departments and individuals to delivering the value promised to customers.

- More appropriate allocation of scarce resources.

- A more market and customer-focused orientation across the organization.

- Better, sustainable financial performance.

KSAM plan format and content

Again, very little has been written about the actual content of key account plans. As the content is specific to each account, and companies consider the material to be highly confidential, general discussion is difficult. However, some elements should be common to most or all plans, which we identify here, but clearly there will be variations depending on, for example, the market sector, the company's business model and the position of KSAM and the key account manager in the organization.

Drivers of format and content

We suggest that the content and the form in which it is presented should be driven by a number of practical principles, relating to the plan's:

- Scope.

- Authority.

- Audience.

- Usage.

- Duration.

Scope

KSAM is much more than a selling activity, so other functions are involved in delivery of its strategies. Furthermore, the account plan is generally the only plan in a supplier's business that is dedicated to an individual customer. The account plan should therefore represent the whole of the supplier's interaction with the key account, not just the endeavours of the key account manager. Unless totally independent of each other on the customer side, it should also represent all product groups and locations.

Authority

Since the plan is prepared by the people who know most about the customer, having consulted any others with knowledge or influence, it should be the most authoritative document the supplier produces relating to the account. It should be neither unrealistically optimistic nor conservative/pessimistic, but should present viable strategies and the most realistic expectations of the future. It may raise questions, but it should also answer them. It is no use to the supplier (or customer) unless it means what it says and will do what it says.

Audience

The plan will be read by a range of readers, from senior managers to operational people, and needs to be intelligible to all of them; therefore it should not assume that they are already well acquainted with the account. The plan needs to understand the readers' context; ensure that they will find what they want to know; and anticipate their queries and deal with them. For example, the executive summary is designed for senior readers who may be reading 20 or more of these plans, so it needs to be a succinct collection of the information they seek, including profit forecasts.

Usage

Initially, the plan is employed to gain the supplier's and customer's commitment. There should be a formal approval process in the supplier, including all functions involved in delivery: without it, the key account manager cannot rely on getting the resources needed to implement the plan. Formal approval from the customer may be a legal step too far, but most of the plan should be shared (or even prepared) with them, to gain their agreement to fulfilling their part of it. Subsequently, the plan should act as a blueprint that is used as a live working document, not an ‘academic exercise’, that guides the activities of the key account manager and team, informs the rest of the company and gains their cooperation with implementation, and is the basis for assessing progress.

Duration

Three years is a minimum span for the plan regardless of sector, and it will be longer in some, e.g. large capital projects. Even in fast-moving sectors, the direction of change is generally known and can be planned for. Failure to do so leaves suppliers ‘on the back foot’, just reacting to external forces and far from control of their own destiny. Normally, plans show strategies and projections for three years, with one year of action. In order to make the case for some strategies which take a while to implement, the plan period should be even longer so that the return on investment can be shown in a realistic timeframe, which will extend beyond implementation and its costs.

Structure and format

Clearly, account plan structures and formats vary, but the ones we have seen show a great deal of commonality. It is no help to a company to use a free-style approach: readers waste time trying to find information that is located and presented differently in each. Similarly, the key account manager's time is better spent on populating the plan than working out how to structure it. For everyone's convenience and comprehension, suppliers should work out an appropriate format and insist that key account managers use it. It should not, however, constrain what they have to say. The length of the plan and level of detail are critical choices. We have read short plans containing meaningless generalities, and long plans specifying an over-detailed breakdown of action that will, and should, be recast by those carrying out the action. While short plans are popular in theory, when the customer represents significant amounts of money, the plan should be of sufficient length to cover the business properly.

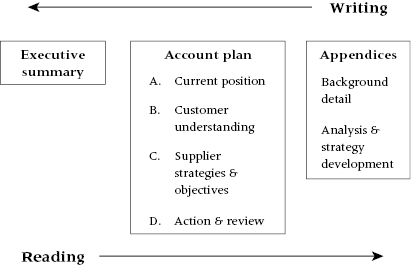

Figure 3 shows how an account plan may be composed. Cherished detail and workings can be housed in appendices where they do not obscure important points: those who wish to go to this depth can find them there, while others need only read the body of the plan to find what they have to do and why. The figure makes the point that plan development starts with analysis and ends with the writing of the executive summary, but the writer should remember that it will be read in reverse order.

Figure 3 Account plan structure

There is a substantial body of scholarly evidence concerning the appropriate components of world-class strategic marketing plans (McDonald 1986; Smith 2003), i.e:

- A mission or purpose statement.

- A financial summary.

- A market summary/overview.

- SWOT analyses on key segments/decision-makers.

- A portfolio summary.

- Assumptions.

- Objectives and strategies.

- Financial implications/budgets.

These elements can be conveniently housed in the structure in Table 1.

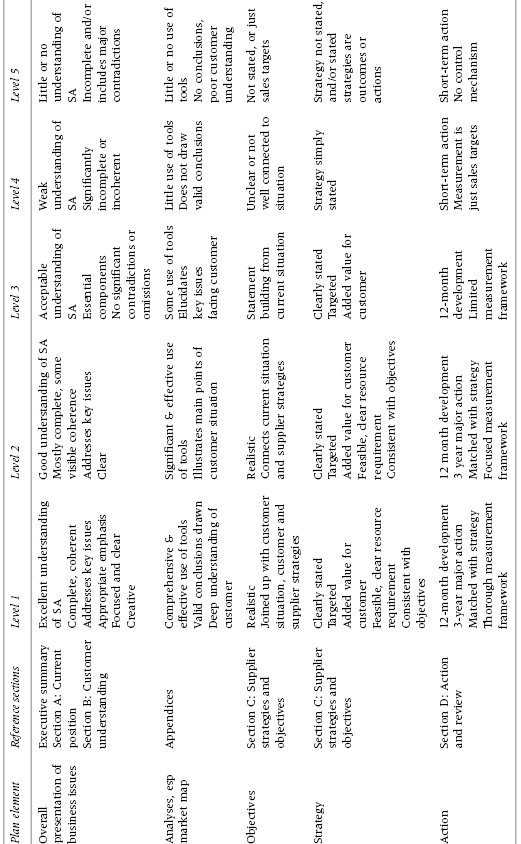

Table 1: Account plan content

| Action plan sections | Section content |

|---|---|

| Account plan | |

| A. Current position | Supplier account team |

| Principal customer relationships | |

| Customer history with supplier | |

| Current issues | |

| B. Customer understanding | Customer's market position |

| Role/participation in marketplaces | |

| Market/business environment | |

| Key external issues for customer | |

| Competitive position | |

| Customer objectives | |

| Customer strategies | |

| C. Supplier objectives and strategies | Customer critical success factors |

| Supplier's environment in this customer | |

| Key external issues for supplier | |

| Competitive position | |

| Supplier objectives | |

| Supplier business strategies and costs | |

| Supplier relationship strategies | |

| Plan risks (external) and dependencies (internal) | |

| D. Action and review | Key action plan |

| Review | |

Plan implementation

The account plan exists to ensure that the right things are planned, agreed and done. Implementation is critical: a plan is only a plan, and although it has a crucial role to play in getting everyone prepared to play their part from top to bottom of both organizations, it clearly should not be mistaken for action. Implementation is not an easy subject, as each company and each plan will have different actions to implement, leading to a huge variety of activities. Since companies are normally unwilling to share their plans outside their organization, making any generalizations about the activities and quality of execution, barriers and successes is almost impossible. However, some characteristics of effective implementation can be identified from comments of key account managers describing what does not work (Wilson and Woodburn 2014).

Requirements for effective implementation

In addition to a good quality plan, implementation requires:

- Cross-functional and cross-location alignment.

- Customer commitment.

- Sufficient resource.

- Identified responsibilities.

- Realistic timeframes.

- Good project management.

- Clear goals and measurements.

- Pragmatic adherence to the plan.

Cross-functional and cross-location alignment: where the team of people required to take action do not understand the purpose, importance and benefit of the SAM programme, they are likely to be reluctant to prioritize its actions against their other activities, and may not make the right decisions about interpretation of the tasks assigned to them. They should be kept fully informed.

Customer commitment: the commitment of the customer is vital: key account managers are wont to complain that they did everything they were supposed to do, but the customer did not. That begs the question of whether the customer sees sufficient value for them in the plan: presumably not, if they did not carry out their actions. Unimplemented plans are often still really supplier sales plans.

Sufficient resource: in our experience, the majority of account plans do not specify the quantity of resources required, and certainly not the cost. Clearly, resource availability and cost are fundamental elements in the assessment of the profitability, desirability and feasibility of a plan. Resource information should be part of the plan: yet few key account managers appear to have access to resource planning and costs.

Identified responsibilities: resources are more often people and time than cash, and a core element of implementation is finding the people to do the work and ensuring that they and their managers accept these responsibilities. Since the perfect marriage of tasks with people and competencies is not always available, assigning responsibilities early and clearly helps to indicate where resource prioritization and building may be required.

Realistic timeframes: key account managers, under pressure from the organization, frequently underestimate the time required to execute action and receive the return, which will only begin to appear when the action has been fully completed. Unrealistic timing expectations can turn real success into apparent failure.

Good project management: strategic account plans will contain numerous projects, some led by the key account manager, others by another function, e.g. product development or supply chain changes. Customers get frustrated if they cannot see good progress on initiatives important to them (and why would they be involved in ones that are not important to them?) and costs tend to mount with delays, so any project management, regardless of who is the project manager, needs to be excellent.

Clear goals and measurements: quantification of expectations is arguably the most straightforward way to ensure that everyone understands what is intended. A mix of ultimate and interim goals helps to keep implementation on track, backed by measurement systems to ensure that the course of progress is accepted by all, and is not a matter for debate. Measurements and collection systems shared with the customer are ideal for all-round clarity.

Pragmatic adherence to the plan: account planning is a not a perfect science, and plans should be applied in a pragmatic and practical way. Accommodations to events and unanticipated details are likely, but in consultation with those involved and within the spirit of the plan. It should be reviewed regularly and changes identified either as minor ‘noise’ or major unforeseen events: the latter should be very few in a well-analysed and constructed plan.

Companies often fail to implement their plans. A plan that is not applied is pointless. It should be a blueprint for implementation across the company, and if it is put away and forgotten, the supplier cannot be surprised if it fails to reach its goals. Unused plans presumably represent poor plans or reactive panic action: neither should be acceptable to companies pursuing KSAM. Bradford et al. (2012) propose that implementation should not be seen as a giant leap of faith at the end of a process but something that is built in throughout the planning process.

Measuring KSAM value

KSAM requires a major commitment from suppliers, not least the time and effort put into the account plans that are the engine central to the initiative and the resource commitments they incur. So it is reasonable to ask, ‘Is it worthwhile?’ or ‘Does it add value?’ However, the question might be asked at the level of an individual key account; or at the level of all key accounts; or of all customers or, in fact, the company overall, so the answer is not simple. Although establishing systems to capture revenues and costs for key customers enables the supplier to monitor value at the first two levels, i.e. for individual key accounts and for all key accounts, measuring the value of KSAM to the company as a whole is clearly more difficult. Indeed, some companies have found that, at the same time as focusing very successfully on key accounts and growing business with them, sales to other customer groups have fallen, so assessing added value from KSAM is complex.

The term ‘value added’ has its origin in a number of different management ideas, and is used in very specific ways by different sets of authors. Most of the ideas come from the USA, and originated in business school and consultancy research in the mid-1980s.

Value-chain analysis

Porter's well-known concept of value-chain analysis (Porter 1980) is an incremental one that focuses on how successive activities change the value of goods and services as they pass through various stages of a value chain. ‘The analysis disaggregates a firm into its major activities in order to understand the behaviour of costs and the existing and potential sources of differentiation. It determines how the firm's own value chain interacts with the value chains of suppliers, customers and competitors. Companies gain competitive advantage by performing some or all of these activities at lower cost or with greater differentiation than competitors.’

Shareholder value added

Rappaport's (1986) research on shareholder value added (SVA) is equally well known: his idea of value added focuses less on processes than Porter's, and acts more as a final gateway in decision making, although it can be used at multiple levels within a firm. The analysis measures a company's ability to earn more than its total cost of capital. Within business units, SVA measures the value the unit has created by analysing cash flows over time.

There are a number of different ways of measuring SVA, one of which, market value added (MVA), needs further explanation. MVA is a measure first proposed by consultants Sterne Stewart in 1991, which compares the total shareholder capital of a company (including retained earnings) with the current market value of the company (capitalization and debt). When one is deducted from the other, a positive result means value has been added, and a negative result means investors have lost out. Within the literature, there is much discussion of the merits of this measure versus another approach proposed by Sterne Stewart, i.e. economic value added (EVA). MVA is one of a number of tools that analysts and the capital markets use to assess the value of a company. As a research topic, it focuses more directly on the processes of creating that value through effective marketing investments.

Customer's perception of value

Value added can also be seen as the customer's perception of value. Unfortunately, despite exhaustive research by academics and practitioners around the world, this elusive concept has proved almost impossible to pin down: ‘What constitutes [customer] value – even in a single product category – appears to be highly personal and idiosyncratic’, concludes Zeithaml (1988), for instance. Research has not found a neat, causal link between offering additional customer value and achieving value added on a balance sheet. That is, good ratings from customers about perceived value do not necessarily lead to financial success (and financially successful companies do not always offer products and services which customers perceive as offering better value than competitors). Nevertheless, the individual customer's perception of the extra value represented by different products and services cannot be easily dismissed: in the guise of measures such as customer satisfaction and customer loyalty, it is known to be the essence of brand success, and the whole basis of relationship marketing.

Accountancy value add

The accountant's definition of value added is ‘value added = sales revenue – cost of purchased goods and services’. Effectively, this is a snapshot from the annual accounts of how the revenue from a sales period has been distributed, and how much is left over for reinvestment after meeting all costs, including shareholder dividends. Although this figure will say something about the past viability of a business, in itself it does not provide a guide to future prospects.

All these concepts of value, although different, are not mutually exclusive. Porter's value-chain analysis is one of several extremely useful techniques for identifying potential new competitive market and key account strategies. Rappaport's SVA approach can be seen as a powerful tool which enables managers to cost out the long-term financial implications of pursuing one or other of the competitive strategies which have been identified, including KSAM strategies. Customer perceptions, especially those of key customers, are clearly a major driver (or destroyer) of annual audited accounting value in all companies, whatever strategy is being used. Walters and Halliday (1997) usefully sum up the value added discussion thus: ‘As aggregate measures and as relative performance indicators they have much to offer … [but] how can the manager responsible for developing and/or implementing growth objectives identify and select from alternative [strategic] options?’

Even if the concepts of customer loyalty and customer satisfaction are insufficient to explain results a link may exist between more complex and wide-ranging customer-orientated strategies and financial results, which requires a far more rigorous approach to forecasting costs and revenues than is common in KSAM planning, coupled with a longer-term perspective on the payback period than a single year. This longer-term cash-driven perspective is the basis of the SVA approach, and can be used as a basis for establishing the value of and in strategic account plans.

Nevertheless, several surveys (e.g. KPMG in 1999, CSF Consulting in 2000) have found that less than 30% of companies were pushing SVA-based management techniques down to an operational level, seemingly because of difficulties in translating cash targets into practical, day-to-day management objectives. Expenditure on key accounts is rarely treated as an investment which will deliver results over an extended period, whereas other expenditure in a company is requested in a business case made via a capital expenditure proposal process and assessed on its ROI over a number of years. The account plan, showing the specific strategies, action, resource requirement and results, is effectively a capital expenditure proposal and should be treated as such, both in its preparation and in its approval. Well-developed account plans are the way forward for these accounts to receive the resource required to deliver the powerful strategies that will make substantial differences to the business.

Conclusion

In order for KSAM to be taken seriously and managed properly in a supplier, it should be underpinned by strategic account plans for individual key customers covering at least a three-year period. These plans need to be of sufficient quality to allow the company to trust them and invest as necessary. Sadly, they often are not of such quality. Without doubt, one of the biggest barriers is the people who are asked to write strategic account plans. Key account managers who have spent most of their career in sales have not previously been required to develop long-term, strategic and financially comprehensive plans with careful, analysis-based forecasts. They need to have the competences of experienced senior executives, fully trained in analytical techniques, financial analysis, strategic planning, political and interpersonal skills: indeed, the very skills required by a successful general manager or chief executive officer.

The determination of the supplier company to achieve such plans is also often in doubt, even though their approach to other forms of planning may be much more rigorous. Unless the company insists on the development of strategic account plans to a satisfactory level, key account managers will interpret its reticence as an escape clause, since many key account managers pride themselves on their action rather than their thinking and planning and, as Woodburn (2008) shows, are rewarded for the former rather than the latter.

Needless to say, however good the plans, they are of very little value unless they are implemented. KSAM is without doubt one of the major challenges facing business today. It is fraught with difficulties in conceiving, planning and implementing it, because it requires major organizational change and substantial shifts in the supplier's view of customers, and in its internal culture, in order to align its R&D, purchasing, manufacturing, logistics, IT, finance, service and other functions with the equivalent functions in its customers' businesses. Clearly, all this cannot be achieved without a good plan. This alignment will only occur in relatively few special cases but, when they happen, such relationships represent a well-spring of profitability for both parties.