Organizational structures in global account management

Abstract

The key elements of global account management organizational structure include the global general manager, global steering committee, global account manager, global account team, information management, executive sponsorship, local account managers, global reporting structure and customer councils. Although the organizational structures of GAM programmes can take a multitude of forms, all of them are variations of three basic approaches, each of which strikes different balances between global integration and local (or national) autonomy. We call the three Coordination GAM, Control GAM and Separate GAM.

Introduction

The organization structure of the global account management (GAM) programme forms the bedrock of the total GAM effort. But there is, of course, no one best way of organizing GAM, as the right structure depends on the company and its situation. This article will describe the various elements that make up a GAM organization. We will also discuss the three major forms of GAM organization, along with their benefits and possible pitfalls.

While there is a large literature on strategic account management (SAM), there is a much smaller one about GAM and even less on GAM organizational structures. GAM research probably started with Yip and Madsen's (1996) article with five case studies. Most recently, Shi et al. (2010) have provided both a full conceptual framework and empirical test. In between, key publications include Arnold et al. (2001a, 2001b), Capon and Senn (2010), Hennessey and Jeannet (2003), Homburg et al. (2002), Montgomery and Yip (2000), Shi et al. (2004, 2005), Verra (2003), Wilson et al. (2002), Yip and Bink (2007a, 2007b) and Yip et al. (2007). Some of these publications address the role of organization structure, but only Yip and Bink (2007a, 2007b) address this issue directly.

Citibank has been pioneering global account management for its corporate customers since the 1970s and has since rebranded and reorganized the programme to better answer customers' needs.

The worldwide customer group (WCG) started in the late 1970s, was rebranded in the mid-1980s and continued to exist more or less in the same form until the mid-1990s. The group worked with about 250 corporate clients. Those companies were all global players, mainly in the chemical, pharmaceutical, automobile and retail industries, but no financial institutions. In some ways, WCG was never disbanded, but the name was dropped in 1984 and brought back in the late 1980s. The WCG was replaced in 1995 with the Global Relationship Bank (GRB) programme. The new GRB organization seeks to create and add more value by focusing on industries. The GRB covers about 1,400 multi-national customers, made up from Fortune Global 500 and other companies with global presence and/or global activity (e.g. some UK financial institutions, such as fund managers, do not have overseas branches but do trade extensively overseas).

Elements of a GAM organization

There seem to be as many organization forms for GAM as there are companies, given the need to tailor for the situation of each company. In particular, each company implements each element of GAM in a somewhat different way, producing unique configurations. These elements of GAM structure include the global general manager, global steering committee, global account manager, global account team, information management, executive sponsorship, local account managers, global reporting structure and customer councils.

Global general manager

A GAM programme needs a global general manager who is responsible for the programme and its strategy and operation. This needs to be a senior manager at the corporate or business unit level. Many companies, however, do not have such a position in place, or in some cases the responsibility is given to a manager who also has other duties. For some smaller global companies, having a general manager who is solely responsible for the development of the global programme is a luxury they cannot justify. DMV International, a European supplier of ingredients for the food and pharmaceutical industries, has its global key account managers reporting into the (European) regional sales manager, who is also responsible for all other sales in that particular region. Even though the regional sales manager strongly supports the global account management, there is still the possibility of conflict of interest between local and global issues.

When there is no opportunity to have a global general manager who is dedicated to the programme, companies should at least use a reporting structure that minimizes conflict. This can be achieved by giving overall responsibility for GAM to a high-level manager who has no direct links with any particular geography. Whether there is a dedicated general manager or a shared one, this person needs to have the authority and the desire to help develop the programme in the best way possible. Many company examples show that as soon as there is a person at the head of the programme who really believes that global relationships are the way forward, things change for the better. For example, when Unilever appointed a new senior vice-president for global customer development, the existing situation, in which there were no systems, processes or real support for the global account managers, started to evolve into a more empowered organization with more dedicated teams, and that is more embedded in the total Unilever organization.

Global steering committee

Many companies with successful GAM attribute part of this success to having a global steering committee. Such a committee typically comprises a group of senior executives committed to the global programme, but with other general responsibilities. The global steering committee will meet on a regular basis to decide on the overall strategy and objectives for the programme and monitor the development. The collective power of the executives should outweigh any country or regional managers to make sure that any conflicts on allocating resources or global–local friction can be easily resolved.

Having a global steering committee means that it is easier for the company to handle the tension that comes with the global–local disparity, and it creates much visibility for the company's dedication to global relationships. Some companies even have separate global steering committees for specific relationships, in which case there is often a direct relationship between the members of the committee and senior managers at the customer or supplier. Admittedly, a structure like this is very costly in terms of executive resources, and will realistically be created for only very special relationships.

Having global steering committees can be just as valuable for a global customer as for a global supplier. In the case of British energy company, BG Group, there are currently two relationships with suppliers that are deemed important enough to invest in a steering committee. For each global relationship, BG Group has established a committee consisting of senior managers from both BG Group and the supplier. These committees meet on a regular basis and aim to focus on strategic issues that arise within the relationships. Both global steering committees are being chaired by a BG Group executive vice-president, which embodies the high level of commitment BG Group has to the global relationships.

Global account manager

A good GAM is key to a successful global account relationship. The GAM is responsible for the relationship with the account and the resulting performance. Ideally, the GAM is dedicated to one global account, although in some smaller companies it is necessary to spread GAMs over multiple accounts. In many less advanced GAM programmes, the GAM is a mid-level manager with a career background in sales. As managing global customers is about more than just the GAM programme, so it is also about more than just sales. More and more companies are starting to realize that the relationship with important global accounts should not just revolve around the transactional aspects but be more integrated with other parts of the company in order to achieve a more rounded relationship that is a good foundation for creating more opportunities between the companies in the long run. Therefore, it is important to realize that the skill set of a GAM is not, as the head of one GAM programme put it, ‘the same set of skills as a local account manager, plus having a passport’.

It is also not unheard of any more to have GAMs who do not have a background in sales. Xerox realizes the importance of knowing the customer's industry and takes this into account when choosing the right GAM for an account. The GAM for global bank HSBC spent a large part of his prior career in finance, and the GAM for the Volkswagen account used to be a Volkswagen employee.

Besides knowledge about the customer's industry, other necessary GAM skills include cultural awareness, team management and sensitivity. In general, a GAM takes responsibility for the strategic planning of the account, deciding on goals, and determining and obtaining the right amount of resources. Furthermore, often the GAM will lead the team of people that supports the global account: the global account team (GAT). The GAM needs to guide the GAT members in their particular roles and help them develop their individual relationships with the account. Sourcing of information is also an essential task for the GAM. They need to be the ultimate expert on the account, and combine all the information that is available with the separate GAT members or local account managers. The GAM should, however, also have thorough knowledge about the capabilities of their own company, and how these can help the customer. At Xerox, many of the GAMs have a background in either Xerox itself or the specific account they are managing. The GAM for Volkswagen has more than 25 years of experience in positions either with or relating to this customer. A complete outsider would have a much harder job getting to know all the ins and outs at both companies, and therefore find it harder to identify combined, or other, opportunities for the two companies.

In terms of organizational position, many companies have a structure in which the GAM reports within the geographic area in which they are based. This occurs when no separate reporting structure exists for the GAM programme. But to avoid conflicts of interest between the global and local parts of the company, it is better to have the GAM reporting to a senior manager at the corporate level.

Global account team

The composition and organization of the GAT provides a good indicator of the level of integration of global customer management (GCM). When a GAT is very informal, and consists only of the different local account managers, then the GAM programme probably focuses only on sales, and the GAM does not have enough authority to be able to take full responsibility for the relationship with the account. A company with an integrated approach to managing global customers will have formal global account teams that are both cross-function and cross-country. For example, DMV International works with global account teams that consist of both sales managers for the account from different geographies and representatives from different functional areas that have contact with the customer (e.g. R&D).

The GAT plays a crucial role in getting the relationship with the customer beyond the transactional phase into a partnership. The GAT needs to implement the global strategy for the account while taking into consideration the existing organization of the company. Having a cross-functional team helps to get all relevant views on board, keeps the links with the different departments, and ensures that the global account organization will not lead a life of its own separate from the existing organization. The GAT is also key in building the network of customer relationships that pulls in many participants from both the supplier and the customer. Building on existing relationships, the GAT can engage the customer in new plans and opportunities.

The team members will also be an invaluable source for getting information from different parts of the customer's company, supported by a good information system that can handle this. In the relationship between ABB and its supplier, Xerox, the latter achieves a broad range of contact points by mirroring the ABB organization. ABB has a group supply chain management function that is divided into direct and indirect activities and a national procurement organization in each of the top 22 countries. Xerox maintains a customer contact person in all of these countries, so ensuring a broad basis for relationship management and information gathering. Furthermore, the team members act as ‘ambassadors’ for GCM in their respective departments, ensuring support throughout the company.

Some companies have full-time team members, but it is not always optimal to have employees dedicated to one account. Best-practice sharing and integration of the global programme with the rest of the company come as important benefits of having GAT members with multiple roles. Which way to go will differ between companies and needs to be determined based on the company's situation.

To develop a global account strategy, Young & Rubicam established a global management structure that oversees both the development and the execution of every global campaign. Global managing directors and their teams represent the core of the company's global management structure. Each global managing director provides a corporate global perspective for each campaign and is responsible for all communications with the client. Team members must be devoted to the client, have a global perspective and a broad understanding of not only their client's markets but also the key success factors of each region. Furthermore, because execution is always carried out locally, the firm must have access to and be able to coordinate a wide network of resources. Few clients begin with the premise of establishing a globally integrated campaign. Typically, campaigns are developed for one country and diffused to other countries once proven successful.

Information management

As managing global customers comes with a complex structure of relationships, measurements and information streams, a sound information-management system is essential for the success of the programme. The GAM needs to be very knowledgeable about the customer and its industry, but they will not be able to gather this information without the help of the GAT and a well-functioning information system. Two types of information management systems are important here: first, the results measurement system and second, the customer relationship management (CRM) system.

Many companies still have trouble getting both types of systems geared up for global relationships. Measurement systems need to track the sales of the global accounts and therefore the results of the GAM programme. A common problem is that most of the current systems identify every delivery address as a separate customer, and when a manager wants to see the results for a complete account, this has to be combined manually, which is complicated by differences across regions. Another common problem is that many GAMs do not have easy access to a good overview of the complete results of their account. Besides missing a good management tool, this can make things very complex when it comes to remuneration of the GAM. Many companies traditionally link remuneration for national account managers to the account's revenues. This link should be less strong for global account management, as it should be based more on long-term relationship development than short-term sales. But not having information on global revenues for an account really undermines the ability to judge a GAM's performance. This shows, once more, how important it is to have the GAM programme integrated within the whole company.

When choosing and implementing a new information system, managers need to think about the necessary capabilities of the system, including tracking global sales and profits. While the situation for sales measurement can be bad, it is often even worse for the internal information systems that support CRM. Almost all big companies have some form of internal information system, such as Siebel, Lotus Notes or Livelink. But when we asked if these systems were used to their full potential, the majority of global managers had to admit that they were not.

Many companies implement these costly systems without thinking about their actual use. Training people how to use them is necessary, but incorporating the actual use in their everyday tasks is at least as important. People will go looking for information at the moment they need it, but what is the incentive for loading information they already have into the system, and how will they find out that there is vital information for them on the system if they do not know they should be looking for it? Often this situation ends up as a negative cycle of thinking: there is no useful information on the system, therefore never going on the system and never uploading information.

HSBC encourages its relevant employees to visit its Lotus Notes system at least once a day to deposit or access information. Other firms, such as engineering company Schlumberger, have integrated the internal information system with measurement and logistics systems, to make using the information system a natural thing to do in everyday tasks.

Executive sponsorship

GAM will be successful only with a high level of executive sponsorship. The complex nature of managing global customers needs a high-level executive to whom to escalate conflicts between global and local business units. Even though the executive sponsor should not be involved in operational problems, having the position in place will give a visible signal to the organization that GAM is something for top-level management, thus helping to gain support and commitment at lower levels. Having executive support also helps in getting essential people and other resources for the global account. So, in addition to a ‘programme champion’ in the form of, ideally, a board-level director who has overall responsibility for the GAM programme, many companies choose to have a system of executive sponsorship for the different accounts that involves more top-level executives.

In an executive sponsorship system for GAM, every global account is assigned a senior manager, such as chief financial officer or chief technical officer, who keeps in contact with a senior manager on the customer side. This shows the customer that it is important to the supplier, and helps to develop the relationship. The executive sponsor will often be able to help the GAM to overcome barriers and to open doors that would be closed to the GAM alone. The executive sponsors should not be assigned at random. Ideally, the executive sponsor is someone with specialist knowledge about the industry of the account, or possibly with a previous relationship with the account. They need to be a good conversation partner for the customer.

Furthermore it is very important that the sponsor be fully committed to the success of GAM. In some companies the executive sponsor also acts as a mentor for the GAM, helping them to set goals and strategy for the account. This system also works for customers with a global supplier management programme. A global purchasing officer for Royal Dutch Shell said: ‘There is endorsement and support for global supplier management from the highest level on. The boss saying “I want it to happen” is not enough, but it does help.’

Local account managers

In general, any company with big international customers will have different national account managers (NAMs) dealing with the separate parts of the account. When the big international customer becomes a global account, these local account managers will need more coordination. Also, the NAM becomes more than a local sales manager. They have to realize that they are part of a global team and that sometimes a global objective will ask for local sacrifices. In regard to global accounts, the main GAM-related task of NAMs becomes the local implementation of global agreements, in addition to the usual selling and maintenance responsibilities for the local unit of the global customer. Therefore, it is important for the NAM to keep informed about activities on the global level. On the flipside, the GAM is dependent on the NAM for information at the national level, in order to get a good overview of the total situation with the account. In a way, the NAMs are the eyes and ears of the global account team. They have the most direct links with different parts of the customer and will gather information not available at the global level. For example, the Unilever GAM for Wal-Mart works with about 50 people worldwide to set foundation objectives and operational guidelines.

Some companies have the luxury of having NAMs who are dedicated to a specific global account, but in many cases they will have to be spread across different accounts, global and otherwise, as the local business volume with the global account is not big enough to justify a dedicated person. But even though these local managers work for the global account for only a small percentage of their time, it is important that the GAM knows exactly who is working on the account. The GAM should be able to communicate with these NAMs on a regular basis.

Sometimes one or more NAMs may even be part of the global account team. As the global account organization, by its nature, is very complex, companies should keep to a minimum changes to the local responsibility for the global account. At Unilever, GAMs complain about the high turnover of personnel on the local level, due to the personal career development strategy that Unilever follows. One GAM said: ‘I have an annual worldwide meeting with all the local managers who are responsible for my account. Every year, half of the people there are new, and I will be outlining my strategy for the account all over again.’

Global reporting structure

The global reporting structure is the backbone of the GAM programme. The reporting structure gives the overall image of what position the GAMs have in the total organization. The position they are reporting to can say much about the GAM programme and the commitment a company has to make it successful. In general, there are three streams of reporting structures: reporting in the geographical organization, reporting in a matrix organization and reporting in a GAM-specific organization. In the first type of reporting structure, the balance of power lies with the country sales managers. The GAM will report into the country manager of the country in which they are based, often the HQ country of the account.

DMV International works with a regional system in which the global key account managers report into their own regional manager. Many of the global accounts have their HQ in north-west Europe, and therefore a lot of the global key account managers report into the same regional manager, which helps with any local versus global barriers, as this manager is particularly supportive of the GAM project. Having a direct line into the country or region is often the first reporting structure with which a company starts off its GAM programme, as it is easier to implement than the other two structures. A negative aspect of this structure is the potential friction between benefits for the country and the global account. A country manager might prefer the GAM to work on the part of the account that is based in their country, as any business with the rest of the account will have no influence on the country P&L.

In the second type of reporting structure the GAM will be positioned in a geographical area and will report to a geographical manager, but will also report to either a corporate executive responsible for global accounts, or a corporate manager of the particular business line in which the account is active. This way it is easier to get a power balance between local and global interests. In the third structure, the power balance lies with the global account manager. They have authority over local account managers, and might even have them reporting to them. The GAM will report to an executive manager responsible for global account management, and the global accounts seem to have priority over other accounts. Citibank global relationship bank (GRB) employees report to both industry groups and country management.

Customer councils

Customer councils are not reserved for GAM only, but they can be particularly interesting in this situation. As having global relationships is a relatively new situation for most companies, customer councils can help determine what services can be developed to really help the customer create added value. In a customer council, relevant executives, ideally as senior as possible, are brought together with the GAM and possibly the global steering committee. These events provide an opportunity to understand the customers' needs in doing global business. The setting is particularly inviting for the customers to open up about their needs, wants and possibly complaints.

Vodafone runs a testimonial programme in the form of a customer council with six global accounts. A two-day advisory board with two senior representatives from every global account was used to form working groups on different subjects that are relevant to global relationships, such as ‘global contracts’ and ‘service management.’ Each work group has a representative of all the six accounts, chaired not by a Vodafone representative but by one of the account representatives. Although Vodafone has 50 global accounts in total, it uses this select group of accounts to test new products, services and ideas, and to roll out these products to the other global accounts when they turn out to be successful.

Establishing a global customer management (GCM) programme is only the start of the process. Suppliers must ensure that their programmes' design and implementation meet the needs of their customers and must refrain from establishing a GCM programme for its own sake. Real competitive advantage comes from a GCM programme that complements customers' business processes, as does Shell's programme for Unilever. This programme is customized to Unilever's needs and focuses on helping Unilever to implement its Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) programme at its plants.

Both Shell and Unilever see this as a partnership in which they can find synergy that gives them an edge over competitors. While Unilever sees Shell as the ideal partner to contribute to TPM, it is beneficial for Shell to customize its GCM programme for Unilever this way, as the TPM knowledge gained helps Shell to become Unilever's preferred supplier for lubricants. As Shell develops a good relationship in more Unilever plants, it can start gaining more leverage through global coordination of the entire relationship.

Different forms of GAM organization

There are many different forms of GAM organization, but they normally seem to be variations on three different approaches: Coordination GAM, Separate GAM and Control GAM. When implementing a GAM organization, a company needs to find a balance between central coordination and local flexibility. Furthermore, the programme needs to be integrated into the total organization of the company in order to create the informal organization that gets the whole company involved in managing global customers. Whatever organization form is chosen, the GAM programme will have a particular effect on the other account organization in the company as it will often change the responsibilities and communication lines for the national account managers. In companies that have various independent national account structures, it may even lead to standardization among these national programmes. These changes will be less intense with Coordination GAM, but the effectiveness of this form can be disputed. The typical sequence is for companies to start with Coordination GAM, then move to Control GAM, then lastly to Separate GAM, although few have gone that far.

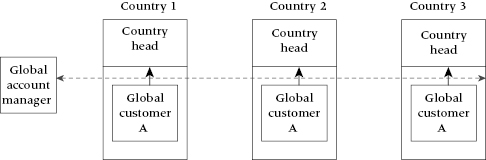

Coordination GAM

The Coordination GAM organization structure takes the existing company organization and adds a coordination layer of GAMs (see Figure 1). The main task of these GAMs is to coordinate among the relevant geographical areas when the customer asks for a global deal. Furthermore, the GAM will try to develop the account into other areas where the company previously had no business. In general, the GAM in a Coordination GAM organization will not have any authority over the local operations but needs to get their consent for any activity on a global level. Many banks use a Coordination GAM structure because of the importance of local relationships and a relatively low need to globally standardize the services provided to global customers.

Figure 1 Coordination GAM

Vodafone, the world's largest mobile telecommunications company, based in the UK, provides an example of a Coordination GAM approach. The company is relatively young and has seen strong growth in the last few years, mainly through takeovers. As there is still a high level of autonomy in the different countries, Vodafone finds it difficult to work with customers on global deals. Previously, the company took an ad hoc approach to demands for global business, often meaning that the national account manager of the country with the biggest part of the global deal would lead the communications with the other involved countries. As Vodafone grew and global business became increasingly more common, the company employed an extra coordination level in the form of the international account manager (IAM).

The tasks of this IAM differ from those of the national account managers. The IAM negotiates central deals, but further local implementation is negotiated on a local level by NAMs. The IAM does not have any control over the P&L of the countries involved. Because of the high level of external growth, the different countries have different structures for national account management, which does not help in making the coordination role easier.

A benefit of Coordination GAM is the ease of implementation, as it does not disturb any existing organization structures. The drawback arises from the GAM programme not being as effective as it could be. The lack of authority means there is room for disagreements between local subsidiaries, and it will often be very difficult to come to a global agreement when all local subsidiaries are working for themselves. For many companies, the Coordination GAM programme is the first step, and the programme often evolves over time into a more structured and powerful organization. Managers should take these future developments into account before embarking on global account management, as sometimes it can be hard to change from the early perceptions about the position of the GAM programme and the position of the GAM. It might be better to incur more disruption in the start-up phase of GAM in order to send the right message: that this company is fully dedicated to making global relationships work.

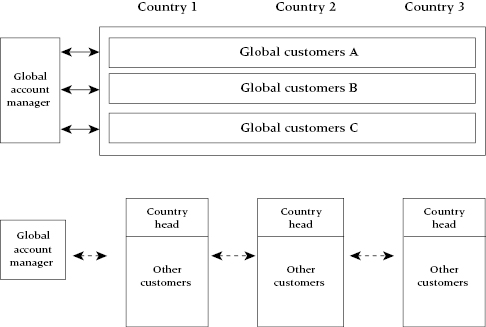

Separate GAM

Separate GAM is in some ways the opposite of Coordination GAM. In the Separate GAM organization, the company creates a completely new, separate business unit for the global accounts (see Figure 2). This can be a complete separation where the employees are dedicated to Separate GAM and the GAM business unit operates its own support activities, such as technical support and sales services. Separate GAM may run some functions as a separate entity, but also share other functions with the organization of the geographic structure.

Figure 2 Separate GAM

In Separate GAM, global accounts that were previously served by several different geographies are completely lifted from the geographic structure to the new business unit. The complete responsibility for the global accounts now rests in the new business unit, which operates alongside the existing geographic units that still take care of the non-global accounts. In addition, the global account manager may have some coordinating responsibility for other customers that have not been pulled into the separate, global organization (as shown in the lower part of Figure 2).

Using a Separate GAM structure for its top 100 or so customers, IBM has three different models in place to deal with account management: territory coverage for smaller customers, an aligned model in which account management is organized around customer industry sectors, and an integrated model. In the integrated model, account management forms a business unit in its own right, and is used for only very large global accounts. The P&L for these accounts is measured on a global basis, and a global team is in place to manage the accounts.

Hewlett-Packard also tried this approach in the late 1990s, breaking out its top 100 accounts. This approach lasted only a short time before it was overtaken by a decision to reorganize HP into a front-end (customer-facing) and back-end (operations) structure.

The main benefit of Separate GAM is the total control the global unit has over the relationship with the global accounts. There is no reason for friction between global and local subsidiaries and it is easier to manage information about this account. The customer gets the attention it needs from a unit that is experienced in handling global accounts and has employees who are dedicated to global accounts. This structure also makes the interface with the account clearer, so that the customer always knows where to go with questions. However, this approach, which can have ‘silo’ aspects, also has its disadvantages. First, it is a very expensive solution that can be implemented only by companies that have a substantial amount of global business. Furthermore, the separating out of the GAM programme means there is less overlap with other account organizations, which means less sharing of best practices.

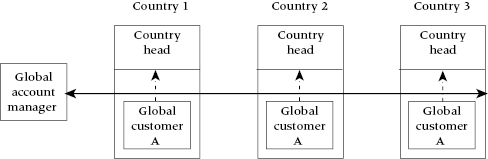

Control GAM

Control GAM is the most common organizational form of GAM. It means that the responsibility for the account essentially lies with the GAM programme and there is some level of authority to enforce that in the local subsidiaries (see Figure 3). Often Control GAM is set up in a matrix organization in which all employees who work with a global account on the local level report not only to their geographical line manager but also to the GAM. The GAM reports to a senior executive at the corporate level, who is responsible for the whole GAM programme, and sometimes also to a regional manager if this is necessary within the company's organization structure. The reporting lines from the local account managers to the GAM and their geographic managers will differ.

Figure 3 Control GAM

Typically, in the early days of a GAM programme, the reporting line to the geographic manager will be a lot stronger than the, often dotted, reporting line to the GAM. When the programme earns more credibility over time, the balance between those two reporting lines typically moves more in the direction of the GAM. In some companies, the regional managers report into the same person as the GAMs or the GAM general manager, typically a vice-president or director for sales. This helps in resolving conflicts, as problems can escalate to the VP's level.

In Control GAM, conflict can arise about authority over the local subsidiaries where global accounts operate. The GAM needs some level of authority to make sure that global agreements can be enforced on the local level, but most companies try to steer away from taking all autonomy from the local subsidiaries. Enforcing plans on local subsidiaries without any discussion leads to resistance towards the global programme, which damages the programme in the long run. Therefore, GAMs should involve local subsidiaries in global decisions that affect their local customers. This not only motivates local managers more to execute these decisions, but involves them as a good source of information about the local implications of global decisions.

The world's oldest advertising agency, JWT (formerly J. Walter Thompson), now part of WPP, runs a Control GAM programme. The agency has approximately two decades of experience with its GAM organization, in which each global client is assigned its own global business director (GBD). This GBD takes responsibility for the qualitative and quantitative results of the business with the client and has executive authority over all business with the client, including the interaction in the different regions. As it will frustrate employees when this authority is used often, the GBD aims to resolve problems by mutual consent, but if there is real friction they have the power to do something about it.

Royal Dutch Shell also operates a Control GAM programme. In 2004, Shell had a standard regional approach (EU/USA/Latin America/Asia), with regional (zonal) account teams and global account teams for the customers selected to be global accounts. Each global account has a responsible GAM who reports to the respective business manager for their sector (e.g. automotive). The global key account management programmes are similar across the different business groups, with minor differences. In most cases the local account managers are dedicated to one account, but in some sectors (e.g. food producers) this is not feasible and the local account managers have to serve several customers. The local account manager reports directly to the GAM, but has a dotted line to the local commercial manager and the local Shell organization, as they depend on local functions such as marketing and supply chain.

Benefits of Control GAM include the balance between global power and local knowledge, and engagement of local managers. For most companies this seems to be the best way to work with global accounts, and the many benefits outweigh the disadvantages of possible friction and the need to make changes in the company's organization structure.

Global account management at Hewlett-Packard

Hewlett-Packard is one of the pioneers and leaders in the use of GAM. We describe the HP programme in some detail here in order to illustrate how the different elements of a GAM programme can work together and evolve.

In the past two decades HP has developed a globally oriented organization to serve strategic global accounts. The original driver for this development was globalization of the computer systems industry and accompanying changes in customer behaviour. Originally, HP's GAM programme covered only certain segments of its business, but as customer needs became more sophisticated, the programme was gradually expanded to the whole company. Key for HP's programme is the balance between a single customer interface in the form of the account manager and account team on a global level, and specialist support for products, service and solutions on a local level.

Globalization drivers affecting the computer systems industry

Since the late 1980s there has been increasing pressure for globalization in the computer systems industry. A growing number of multi-national customers have centralized or coordinated purchasing and vendor selection. These multi-nationals require vendors to have the ability to serve them as a single entity around the globe. Furthermore, the customer focus has shifted from the product itself to its functionality, which has increased customer demands for global standardization and consistent services. Fast-changing technology accelerated the evolution from centralized mainframes to decentralized computer networks that are linked worldwide. Additionally, the importance of continuous innovation and time to market increased because of the opportunities that fast-changing technology provided. All these changes led to a revision of the traditional relationship between vendor and customer. Customers expect vendors to be strategic partners who understand their business needs and are able to provide appropriate products, services and solutions to their activities across the world.

HP strategy towards global account management

HP wants to be the trusted information technology (IT) advisor for its global accounts by increasing customer intimacy and satisfaction. This strategy is supported by building a strong competency in higher value-added services and driving HP further up the IT value chain. With the aim of providing direct customer support for key global accounts, HP has been expanding its global account management programme since 1991.

Currently the top 200 corporate accounts are classified as global accounts and handled in the HP GAM programme. Important components of this programme include having unified, empowered corporate account teams combined with strong specialist support, assigning executive sponsors for major accounts, having a worldwide company look and feel, and selecting the right accounts to be a corporate global account.

HP's account organization model

Creating a single interface to the account, HP designates a global client business manager (GCBM) for every global account. This GCBM is assisted by a global account team that comprises different HP disciplines. For major accounts, a high-level executive is also assigned to support the account interface. This encourages HP executives to be actively involved with accounts that are considered crucial to the company's long-term success. Furthermore, customers highly appreciate this direct connection to upper management. In addition to the global account interface, the customer can rely on local support. A number of regional account managers are responsible for the local management of the account. Product, service and solution specialists also work on this local level. These specialists can give the customer dedicated support and create a local closeness of experts to the different customer divisions.

To achieve a worldwide company look and feel, HP works with globally uniform commercial terms, infrastructure and company policies. Synchronization of company processes over the different regions ensures the delivery of similar services worldwide.

Role of the global client business manager

The GCBMs play a critical part in HP's GAM programme as they are responsible for the worldwide relationship with the customer. Key responsibilities of the GCBM include:

- Identifying and creating ‘valued’ opportunities that are beneficial to both the customer and HP.

- Marshalling and coaching HP and partner teams to pursue opportunities and execute commitments made to the customer.

- Measuring and improving customer satisfaction and loyalty.

- Meeting HP financial targets.

- Providing the primary focal point for managing executive communications and relationships between HP and the customer's management.

To live up to these responsibilities the GCBMs need to understand and communicate HP's capabilities in products, services and solutions. They also need a thorough understanding of the customer's business and business environment.

Selecting global accounts

Obviously, not all of HP's accounts are suitable for global account management. A typical global account would be a large multi-division, multi-national company that is one of the leaders in its markets. The customer does significant business with HP or shows potential for such. A good fit with HP's market focus and culture is also necessary to ensure the optimal results from global account management.

Value of the GAM programme to customers

Customers generally respond positively to the HP GAM programme. Most global accounts have a complex multi-national decision-making process. Therefore, HP's single focal point for account communications provides the clarity that customers value in a supplier. As the account team has a thorough understanding of the customer's business, they are able to bring proactive solutions and deliver best practices. The empowered GCBM and account team ensure fast decision making, which customers also appreciate. HP sees the programme as an important differentiator from its main competitors such as IBM and Xerox.

In line with its strategy, HP aims for long-term, mutually beneficial relationships with its strategic customers and makes major commitments to achieve these. Since its inception, HP considers its GAM programme to be a very successful way to realize these relationships and to develop a truly global organization.

Conclusion

This article shows that there is no single best way of organizing GAM. Managers need to find a suitable implementation of GAM elements for their own company situation. However, some best practices are valid for most companies:

- The right balance of global control and local flexibility.

- High-level executive support for the GAM organization.

- A clear, formal GAM programme that is neither too ill defined nor too rigid, and that is visible to the whole company.

- Integration of the GAM programme with the rest of the company organization; it needs to become part of the company culture.

- A cross-functional global account team.

- A workable and effective balance of power within the GAM programme.

There is plenty of scope for further research. Key issues to be explored include:

- When and how to make the transition from one structure of GAM to another.

- The performance consequences of different types of structure.

- Which types of processes best support the different structures.

- What variants there are for the three structures.

- How the different elements of organization structure can be best configured together under the different modes.

Note

Reproduced with the kind permission of Oxford University Press, originally Chapter 4, ‘Structuring the global customer management programme’ in Yip, G.S. and Bink, A.J.M. (2007) Managing Global Customers: An Integrated Approach.