CHAPTER 10

Investing in Microf inance

And while the lack of financial services is a sign of poverty, today it is also understood as an untapped opportunity to create markets, bring people in from the margins and give them the tools with which to help themselves.

Kofi Annan1

Microfinance has grown into an established asset class. Private institutional investors in particular have considerably contributed towards its impressive growth in recent years.

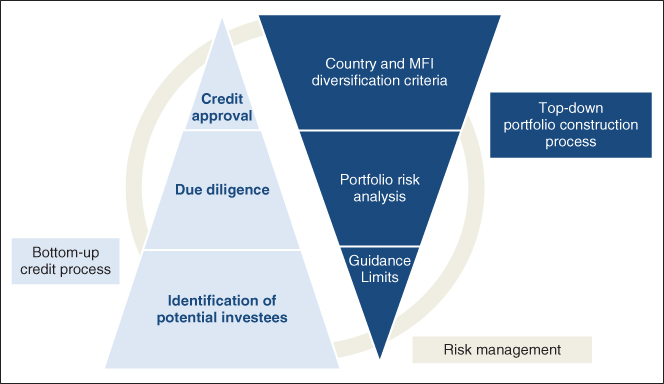

The investment process is crucial for the quality of a microfinance portfolio, and a professional microfinance manager will always combine a top‐down portfolio construction process with a bottom‐up investment approach. Only a meticulous analysis of an MFI locally will allow for careful selection of investments.

Investments in microfinance have an attractive risk‐return ratio, both individually and in the overall portfolio context. The outstanding characteristics of investments in microfinance act as diversifiers of an investor's total portfolio.

10.1 MARKET DEVELOPMENT

To begin with, predominantly development institutions such as the World Bank or the KfW Development Bank were investing in microfinance to employ their financial means sustainably in financial inclusion and the fight against poverty. Today, the asset class has established itself with institutional and private investors alike. Pension funds, foundations, fund of funds or insurances invest billions of dollars in microfinance. Typically, investors put their assets via funds into microfinance, ultimately to ensure a professional and efficient management of their assets. The bundling of assets in such MIVs has multiplied by ten in recent years to a staggering $11.6 billion at the end of 2015 (see Figure 10.1).

FIGURE 10.1 Assets in Microfinance Funds (in Billion $)

Data Source: Symbiotics (2016)

Albeit the volume of MIVs is rather small in comparison with international bond and stock markets, this asset class has well and truly outgrown its shoes. The fact that the share of institutional investors – who can document a rigorous and sophisticated selection process of their investment vehicles – has risen considerably over the years is a result of the professionalization of the microfinance sector. Microfinance no longer represents an exotic niche investment vehicle, but has become an integral part of asset allocation in general. Private investors have taken the place of development finance institutions (DFIs) as the main sponsors in microfinance (see Figure 10.2).

FIGURE 10.2 Microfinance Investors

Data Source: Microrate (2013b)

10.2 MICROFINANCE INVESTMENT VEHICLES

Investing in microfinance institutions directly is a perfectly feasible option. Some DFIs and major pension funds are doing exactly that. In most cases, however, the lack of experience with this choice and the high costs incurred do not argue in favor of it. For this reason, professionally managed investment funds with efficient access to MIVs are an undoubtedly more effective choice.

Fixed‐Interest Investments and Equity Commitment

Similar to traditional investment funds, investments in microfinance offer the option of fixed income investments or investments in stocks. For this reason, there are funds that exclusively invest in fixed income papers, or solely in equity capital. Other funds may prefer a mixed portfolio. Fixed income in this case refers to the fact that investments are only made in loans that go to MFIs. On the other hand, funds with equity exposure lend equity capital to the MFIs. At 80 per cent, the global market for fixed income investments is considerably more substantial than the stock market with its roughly 20 per cent share.2

Thematic Funds

Microfinance investment funds may have a thematic focus, meaning that a fund is mainly used to promote and develop a particular topic such as agriculture, health, education or energy. Thematic funds issue loans and equity to MFIs that exclusively deal with the respective topics or engage in their funding (see Figure 10.3). Another possibility is to distribute funds to MFIs that commit to implementing the capital they receive in the name of these pre‐defined goals, albeit they may additionally use the remaining funds to issue micro loans for other goals.

FIGURE 10.3 Fund Characteristics

Source: BlueOrchard Research

Public–Private Partnerships and Risk Sharing

The risk sharing between public and private investors is an appealing aspect of several microfinance funds. Several microfinance funds are set up as public–private partnerships, where public and private investors invest in the same funds. Very often, public investors provide a guarantee in the form of horizontal and vertical risk sharing. Horizontal risk sharing means that a public institution carries a certain share of potential risks. In the event of a 5 per cent loss, and in the case of horizontal risk sharing of 50 per cent, this public institution would carry half of the loss, and the private investors the other. With vertical risk sharing, public investors bear the brunt of the risk to a certain degree. This is also referred to as first‐loss tranches. Vertical risk sharing of up to 20 per cent means that the public institution takes over losses of up to 20 per cent of the capital. Private investors are only affected by losses that exceed the 20 per cent mark.

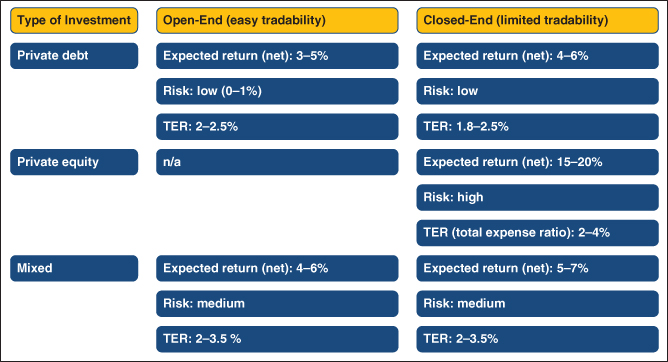

Closed‐End vs. Open‐End Funds

As MIVs, i.e. investments in MFIs, predominantly feature in private markets with limited tradability, closed‐end funds have several advantages over open‐end structures.3 Their fixed maturities manage to achieve a higher level of investment. Closed‐end products at the same time are better suited for long‐term loans, and can be managed more efficiently: no trading of shares needs to be assured, and their net asset value (NAV) needs to be assessed and published less frequently. Due to a limited circle of investors, the implementation of regulatory guidelines is usually easier than in open‐end funds, and annual audits are less elaborate. For closed‐end funds this results in lower costs and higher net returns.

Costs

At 2 to 4 per cent annually (TER), the management costs of microfinance funds are traditionally slightly higher than those of traditional investment funds, the reason being the labor‐intensive analyses of MFIs. Professional microfinance fund managers are represented by their staff in the regions in question, which allows them to assess MFIs locally. This includes due diligence visits to MFIs that may take several days, during which interviews are conducted with the board of directors, the management, the MFI's employees and clients, and also loan documentations are reviewed.4

Microfinance Funds: Possible Pitfalls

As with any other financial investment, investing in microfinance funds is a question of diligence. Alongside the well‐known factors, microfinance features additional characteristics that need to be taken into consideration.

Regardless of whether a microfinance fund provides MFIs with equity or debt capital, investments are largely conducted in private markets and are not traded on a stock exchange. Investments therefore have to be identified, reviewed, negotiated and structured locally. In many cases, critical information is only available locally and may be coded with local idiosyncrasies. Thus, the decisive factors in the choice of a fund manager are how well and in what regions the manager is represented by local staff, and in addition to that, how familiar the manager is with the local and regional setting and the economic and legal framework. Being proficient in the local language is mandatory, especially when conducting interviews with clients, reviewing and negotiating contracts. During the investment process, it is advisable to investigate whether the manager bases their decisions on their own research or whether they buy their data from third‐party suppliers.

As mentioned earlier, the debt to equity ratio is around 80 to 20, i.e. 4 to 1. Apart from genuine private equity funds, therefore, in most cases a manager's loan experience is crucial. Investors are advised to carefully examine a fund manager's degree of experience. Among other factors, the investment team's specific wealth of experience, as well as the default rate of a loan portfolio, are clear reference points when it comes to assessing the quality of the loan process. It is equally relevant to establish the manager's experience in handling problematic loans. With private equity funds and mixed funds, a careful screening of the assessment methodologies and policies for equity investments is inevitable. Mixed funds additionally carry the risk of conflicts of interest, as in some cases the same MFIs are funded by means of debt capital and equity at the same time.

FIGURE 10.4 Default and Loss Rate5

Data Source: J.P. Morgan (2015); BlueOrchard

Microfinance funds are known to predominantly invest in developing countries, which are as a rule less politically and economically stable than industrialized countries. A microfinance manager therefore ought to have the skills to hedge the interest rate risks of local currency areas as well as exchange rate fluctuations. Country risks such as political crises and natural disasters are other well‐known and monumental challenges that MIVs have to face. Diversification across different countries and regions is a crucial evaluation criterion when it comes to funds. Loans that have been granted or equity stakes are usually not traded on a stock market, which explains the relevance of the liquidity management.

If a fund can fall back on a bank line, potential funding gaps can be bridged. A bank line allows for flexibility on the investor's side and can be used to temporarily finance applications for and redemptions of shares in a fund.

10.3 THE INVESTMENT PROCESS

As the previous chapter has illustrated, microfinance funds invest in MFIs, and their analysis and selection processes are extensive and elaborate (see Figure 10.5). With respect to the portfolio, there are questions regarding its geographical diversification and extent and limits thereof, or regarding the nature of the risk‐return profile. This profile is usually determined by means of a top‐down process and determines the allocation of the assets. The analysis and selection of MFIs on the other hand follows a bottom‐up process. A professional fund manager will combine both processes with a rigorous risk management.

FIGURE 10.5 Microfinance Investment Process

Source: BlueOrchard

The professionality of modern microfinance also manifests itself in its investment process. It is perfectly in line and up to date with what is considered best practice in other asset classes such as stocks, bonds or private equity.

Strategic and Tactical Asset Allocation

In simple terms: the result of the top‐down process is a structure that defines the cornerstones of an investment strategy. It aims for optimal diversification across countries, regions and individual investments. Establishing this structure, however, is by no means trivial, as there are different dimensions that have to be considered and brought in line with one another. The following questions have to be addressed in this process:

- Which countries should be invested in?

- What (maximum) amount should be invested per country or region?

- What overall risk is acceptable?

- Which MFI segments (tiers 1, 2 or 3) should be invested in?

- How many MFIs should be included in the portfolio?

- What (maximum) amount should be invested per MFI?

Only a wealth of experience and in‐depth knowledge of the global microfinance and financial markets will answer these questions. Successful fund managers adamantly have to know the risks involved with individual countries and regions and gauge them accordingly. They have to be able to pinpoint the MFI segments in each country and region that are attractive and ultimately investible for international investors.

The percentages for the strategic asset allocation are defined based on the country analysis (see Figure 10.6). Strategic asset allocation is rather rigid in its design and focuses on long‐term goals. For this reason, tactical fluctuation bands are established that allow the fund manager a certain degree of flexibility in reacting to favorable and adverse conditions. This may be helpful especially when the political framework of a country takes a turn for the worse and emphasis on this particular country has to be tactically reduced. The contrary may be the case when a country becomes particularly attractive, which would lead to a temporary increase in portfolio weighting.

FIGURE 10.6 Asset Allocation

Data Source: BlueOrchard

Analyzing and Selecting MFIs

There are around 4000 microfinance institutions. A single microfinance fund – depending on its size and geographical orientation – invests in about 50 to 200 institutions in this universe. Apart from the central risk‐return considerations, several other factors influence the selection process.6

A microfinance fund manager's main task is to select the “right” MFI. The MFI analysis and selection process is crucial for the quality of a portfolio. The following illustrates the seven steps of this process (see Figure 10.7).

FIGURE 10.7 Process of Analyzing and Selecting MFIs

- Define selection criteria

Along with the benchmark figures defined by strategic asset allocation, further (quantitative or qualitative) basic selection criteria for investments may be either mandatory or supplementary, depending on the mandate. These additional conditions further reduce the investible universe.

- Pre‐DD committee review: screening and approval of due diligence

Once the selection criteria have been defined, the screening follows. This means that MFIs are identified that appear to meet the criteria. Special databases and networks are used in this step.

At this point, it will also be necessary to establish how much equity and debt capital these individual MFIs can or should raise.

The information that has been gained so far is by no means sufficient to make an investment decision; however, it is usually substantial enough for a preliminary report on the choice of interesting MFIs. This report is typically compiled by an investment specialist. Due to possible conflicts of interest, she or he has no discretionary competence. Therefore, an investment committee will be needed to either terminate the process, seek more information or grant the investment specialist permission to continue with the process.

If the fund manager pursues a hedging strategy with respect to currency and/or interest rate risks, it is further advisable to assess the hedging conditions early on in the process. The approach again depends on the individual fund manager. Some will hedge all transactions against interest rate and currency risks, others will only partly do so, and some investment managers will deliberately take a currency and interest rate gamble in the hope of an added profit alongside interest payments.

-

Conduct on‐site due diligence

As soon as the investment committee has given the green light, an in‐depth analysis will be conducted locally in order to gain a better understanding of the MFI and the essential risks on hand. Previous to that, an investment specialist will have gathered additional information from the MFI and prepared further steps accordingly. These preparatory operations will allow the investment specialist to travel to the resident country of the MFI under investigation.

What follows is the due diligence investigation of the MFI, which usually takes a few days. The information gathered locally will then be presented in a detailed report and handed over to the investment committee for further inspection.

- Assign rating

The due diligence of the MFI informs the fund manager about the quality of an MFI. For an even more accurate assessment of an MFI, it can be assigned a rating, which pools all the relevant information. Quality is thereby defined as a probability of default, meaning that the rating should indicate the probability of an MFI sliding into financial difficulties.

Larger MFIs have already been rated by well‐known rating agencies such as Fitch, Standard & Poor's or Moody's and may serve as a reference point for the fund manager's own judgment. Most MFIs, however, have not been rated yet – all the more reason why a fund manager's own evaluation may even be of vital importance to the MFI itself.

The rating methodology depends on the fund manager, though the calculation of a rating is highly complex and as a rule can only be performed by the most proficient service providers. The rating assignment process is ideally performed on several levels in a bid to avoid any conflicts of interest. Hence, although the investment specialist may well make suggestions for the rating, they will not be in a decision‐making position. In many cases, a rating will therefore be confirmed by a committee consisting of investment specialists, portfolio managers and risk managers.

- Internal investment committee review

Due to conflicts of interest, investment specialists do not decide single‐handedly whether an investment in a particular MFI ought to be encouraged or not. They submit both their own proposal and the rating to the investment committee for approval.

There may be several investment committees along the fund hierarchy, which is why an investment proposal at times has to be approved by more than one committee. Combinations between internal investment committees at fund manager level and external committees for the fund, which is a separate legal entity, are quite common. The external thereby superordinates the internal committee.

- Disbursement and hedging

The decision of the investment committee is followed by a series of operative steps to complete the transaction. First of all, the loan contract with the MFI is concluded and signed by both parties to be legally binding, then the contract is transferred to the custodian – usually a bank – for safe custody.7

What follows now are the hedging transactions, if at all provided. This encompasses additional tasks for the fund manager. They will begin to evaluate and select suitable hedging instruments and partners as well as structure contracts that are in line with the characteristics of the loan.

- Monitoring

During its term, the investment is closely monitored, both virtually and locally. To enable the fund manager to monitor the investments from far, the MFI is obliged by the loan contract to disclose certain information to the manager in a predetermined frequency. Special occurrences are to be communicated immediately.

Ideally, these reports are evaluated by the investment specialists and risk managers involved. They assess the general situation of the MFI and check for breaches of the loan contract. In the event of negative developments or breaches of covenants, the risk management takes over the case and devises an adequate course of action.

10.4 LOAN AGREEMENTS AND PRICING POLICY

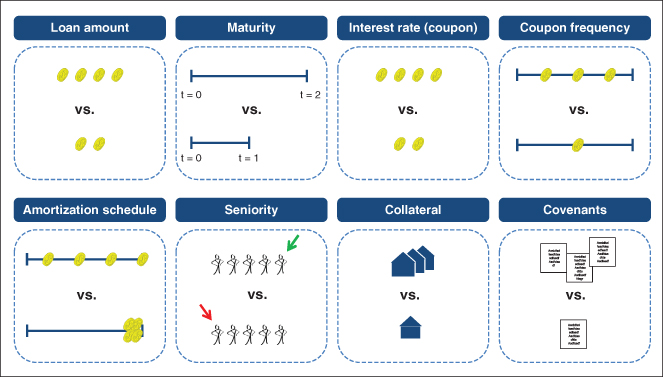

The result of any investment process is a contract between the fund and the MFI, or – in the case of equity investments – the fund and the shareholders of the MFI that sell the shares to the fund. A bilateral contract has to be negotiated that meets the requirements of both parties, unlike listed investments, which do not require contract negotiations, as only standardized contracts can be purchased.

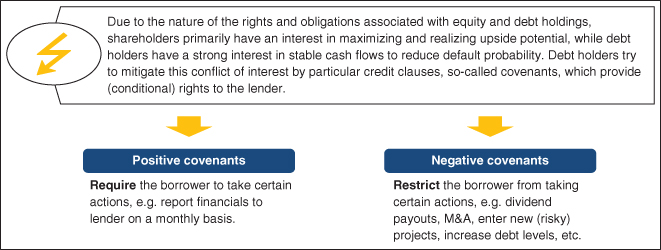

Loan contracts contain a series of parameters that are negotiated between the fund manager and the MFI (see Figure 10.8). First of all, there is the loan amount as well as the maturity of the loan, the interest rate and its repayment frequency. Furthermore, there may be amortizations that have to be effectuated during the maturity. The loan has to be repaid in installments during its maturity, which mitigates the loan risk for the fund. The contract will also stipulate the seniority of the loan. This is relevant, should the MFI experience repayment difficulties, as loans with a high seniority are given precedence over others. The loan contract will further define the collateral that secures the loan, for example, buildings or inventory values. Ultimately, the contract also includes a number of sub‐covenants that the MFI has to abide by (see Figure 10.9).

FIGURE 10.8 Negotiating Loan Details

FIGURE 10.9 Positive and Negative Covenants

Loan covenants are of utmost importance in avoiding, or at least mitigating, any conflicts of interest between the owners of an MFI (the shareholders that are represented by the management) and the lenders of debt capital. Conflicts of interest between shareholders and lenders of debt capital are primarily the result of different expectations with respect to prospects of success. Shareholders may at worst suffer a loss of 100 per cent; their chances of profit, however, are potentially unlimited. Sponsors of debt capital, on the other hand, may equally suffer a total loss at worst, but they do not have any other chances of profit beyond the interest payments. In the event of insolvency, debt investors will be served before equity holders. Shareholders therefore have a strong incentive to maximize their chances of wealth by increasing their risk accordingly. Lenders of debt capital, however, prefer stable cash flows, predictability and material security.

To put it more simply, there are two types of covenants that may be employed by sponsors of debt capital: positive covenants, which largely cover reporting duties, and negative covenants, which oblige the MFI to refrain from certain actions.

Typically, these kinds of covenants apply to investment, payout or funding policy. Covenants may for instance restrict investments, prohibit dividend payouts or ban additional borrowing of debt capital.

The parameters mentioned above have a direct influence on the financial terms. The pricing of a loan largely depends on how secure its repayment is: the safer the repayment, the more favorable the terms that can be offered to the MFI.

Covenants thereby tend to have a favorable influence on a loan's default probability, as they are instrumental in stabilizing streams of cash flows. Shorter maturities also go hand in hand with a lower default probability, because longer maturities are synonymous with uncertainty. Collateral, amortization and high seniority, however, have no influence on default probability, yet they reduce a potential amount of loss. A fund manager's main goal therefore is to draft an optimal loan contract that will forge consensus of all parties.

10.5 MICROFINANCE IN THE OVERALL INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO

Before the investment process is initiated, and before the most skilled fund managers and funds are evaluated and the microfinance portfolio is compiled, the weight of microfinance investments in the overall portfolio has to be determined. Investments in microfinance yield an attractive risk‐return rate, both on their own and in the context of a portfolio, and they are a sensible course of action as they diversify the overall portfolio.

Microfinance correlates little or negatively with conventional asset classes such as bonds, shares or hedge funds. As a result, a portfolio with microfinance investments can yield higher returns than a portfolio that merely invests in conventional asset classes – at the same level of risk.

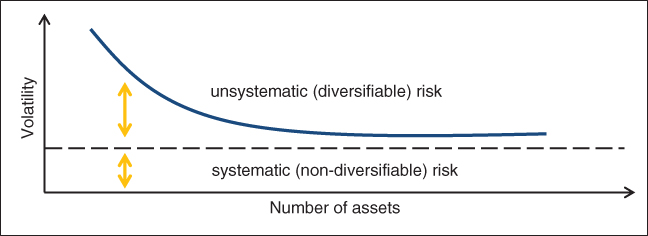

The economist and Nobel Prize Laureate Harry M. Markowitz proved by means of his modern portfolio theory (MPT) that a portfolio's risk can be reduced by adequate diversification. The risk of a diversified portfolio of assets is therefore considerably lower than that of a portfolio with a small number of assets (see Figure 10.10). Diversification lowers or mitigates the unsystematic risk so that the overall portfolio will only contain the market risk, i.e. the systematic, non‐diversifiable risk. The diversification effect is based on the correlation (statistical interdependence) of the different assets in the portfolio. While positive correlations point to a parallel movement of return of both assets, negative correlation as a rule leads to counter movements, i.e. diversification.

FIGURE 10.10 Diversification

Efficient Frontier

The efficient frontier concept was introduced by Markowitz in 1952 and is a cornerstone of MPT. It establishes the set of optimal portfolios that offer the highest expected return for a defined level of risk or the lowest risk for a specific level of expected return. Figure 10.11 displays two portfolios that carry an identical level of risk, but generate different returns. Therefore, only the portfolios on the solid line (efficient frontier) are efficient. They yield a higher return with the same risk (volatility) than the portfolios on the dotted line. The dot indicates the mean‐variance portfolio, which is the portfolio that yields a specific return with the lowest risk.

FIGURE 10.11 Efficient Frontier

Data Source: Markowitz (1952)

Correlations naturally follow suit when the values of the different investments change. Investors therefore reshuffle their portfolio based on these changes. However, the changes in correlations between the different asset classes are rarely significant enough to have a dramatic effect on risk minimization.

Sample Portfolio: Microfinance in the Portfolio Context (According to Markowitz)

A sample portfolio will serve to illustrate how the value added to a portfolio by microfinance is assessed, by means of six sample asset classes that create a portfolio:

- Microfinance

- Cash

- Government bonds

- Stocks

- Stocks – emerging markets (EM)

- Hedge funds

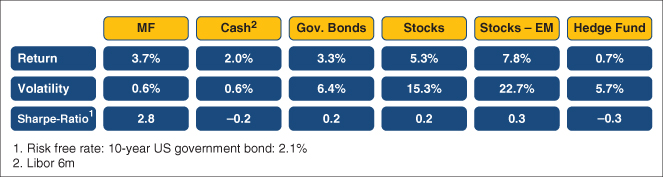

Figure 10.12 displays the key performance measures of asset classes i.e. their respective indices. Over the period of ten years, emerging market stocks (MSCI EM index) yield the highest return at almost 11 per cent annually, followed by stocks of industrialized countries (MSCI World) at 6 per cent. Government bonds (Morningstar government bond index) yielded a return of 3.3 per cent a year, MIVs (SMX – MIV Debt) yielded 3.7 per cent, cash investments (six‐month US‐Dollar LIBOR) 2 per cent, and hedge funds 0.7 per cent (global hedge fund index). While stock indices were particularly subject to turbulence during the financial crisis, microfinance and the money market managed to remain largely unscathed.

FIGURE 10.12 Key Performance Indicators of Asset Classes (1 January 2005 – 31 December 2015, Based on Monthly Returns in $)

Data Source: SMX, Bloomberg

A look at the relation of the risk and the returns (Sharpe ratio) clearly reveals the appeal of MIVs. Taking account of the volatility, the return of 3.7 per cent p.a. yields a Sharp ratio – i.e. a risk‐adjusted return – of 2.8 per cent and achieves the highest ratio of all the asset classes in the portfolio.

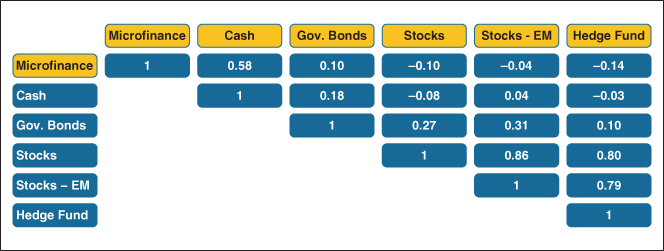

Figure 10.13 reveals that MIVs in fact correlate little with other assets. The value of the so‐called correlation coefficient may figure anywhere between minus 1 and plus 1. A correlation of plus 1 indicates perfect positive linear correlation between the two asset classes, whereas a correlation of minus 1 indicates a perfect negative correlation. A correlation coefficient around zero indicates no linear correlation.

FIGURE 10.13 Correlations

Data Source: SMX, Bloomberg

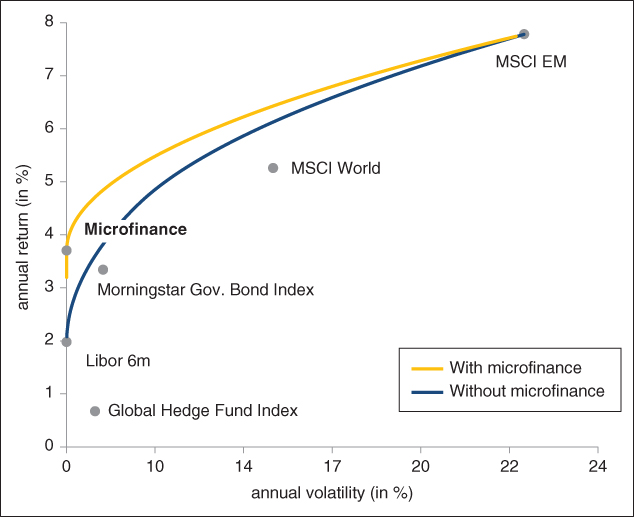

An efficient portfolio is one where the return of a portfolio cannot be increased with a given risk, or where the risk cannot be lowered with a given return. Figure 10.14 illustrates that microfinance boosts a portfolio's efficiency. This essentially means that including microfinance in a portfolio generates a higher return at the same level of risk than a portfolio that only consists of conventional asset classes.

FIGURE 10.14 Microfinance in the Overall Portfolio

Data Source: SMX, Bloomberg

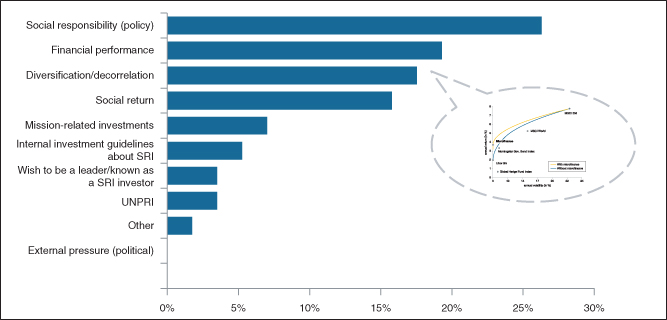

10.6 INCENTIVES FOR INVESTING IN MICROFINANCE

What motivates public and private investors to invest in microfinance? The University of Zurich's Center for Microfinance and BlueOrchard thoroughly investigated this question in a joint comprehensive survey – the ‘Swiss Institutional Investors Survey 2014’ – among institutional investors. The answers of the respondents revealed that a great number of institutional investors invest in microfinance because of SRI guidelines imposed by corporate governance. The survey also disclosed that the stable financial performance of microfinance and its diversification are the key incentives for investments, followed by social return, as shown in Figure 10.15.

FIGURE 10.15 Incentives for Investors to Invest in Microfinance

Source: BlueOrchard and the University of Zurich ( 2014 )

Institutional investors named risk and return as the decisive factors for their investment decisions (see Figure 10.16). The sample portfolio illustrates that microfinance has a more attractive risk‐return ratio than conventional asset classes. At the same time, portfolios that have been diversified by microfinance become more efficient.

FIGURE 10.16 Criteria for Investment Decisions

Data Source: BlueOrchard and the University of Zurich ( 2014 )

10.7 PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS

Microfinance has grown into an established asset class. Private institutional investors such as pension funds, insurances or funds‐of‐funds in particular have considerably influenced this impressive growth in recent years. Investors appreciate the stable returns and outstanding diversification properties of this asset class. Investments are predominantly made via investment funds to ensure that they are managed professionally and efficiently. This also offers investors the opportunity to make their investments alongside development banks, benefiting from their experience and partly also from their risk‐sharing mechanisms.

The investment process is crucial for the quality of a microfinance portfolio, and a professional microfinance manager will always combine a top‐down with a bottom‐up approach. The top‐down process determines the basic parameters of a portfolio, such as geographical allocation or the risk‐return profile. The bottom‐up approach includes the identification, analysis and ultimately the selection of individual investments. Only a meticulous analysis of an MFI locally will allow for careful selection of investments.

The investment process terminates with the actual loan contract negotiations between the fund manager and the MFI. The aim is a contract stipulating the amount of loan, maturity, interest rate, collateral and particularly covenants that are acceptable for both parties involved. Covenants are vital aspects of a loan contract, as they mitigate conflicts of interest between shareholders and lenders of debt capital.

MPT is instrumental in the search for the optimal portfolio that maximizes returns with a given level of risk. Microfinance's negative correlation with cyclical asset classes such as stocks and hedge funds over recent years amply shows that a portfolio including microfinance yields a higher return with the same risk factors (volatility and economic cycle).

Institutional investors base their decision to settle for microfinance on an internal strategy that promotes socially responsible investing, followed by the attractive financial returns and outstanding diversification opportunities of microfinance.

In conclusion, microfinance is not only attractive as an investment opportunity, but its outstanding diversification properties in a portfolio truly make it one of a kind.