CHAPTER FIFTEEN

INTRODUCTION

The vast majority of the 1000-plus NCAA member institutions find sports to be a money-losing endeavor. These losses are expected at each of the nearly 300 Division II and over 400 Division III member institutions, where the athletic department is viewed as an integral part of the university, as indicated by the Division II and Division III philosophy statements. The financial expectations for the members of Division I are typically quite different, with intercollegiate athletics viewed as a potential money-maker. However, as indicated by the NCAA’s most recent financial survey covering the period from 2004–2006, published in 2008, the potential is rarely realized, and the results are usually the same as in Divisions II and III. If institutional support is excluded, none of the 118 members of Division I-AA or the 93 members of Division I-AAA operated profitable athletic departments in 2006. The median I-AA institution lost $7.1 million and the median I-AAA member lost $6.6 million that year.

The financial expectations are much greater for the 120 members of the big-time world of college sports that is NCAA Division I-A. Nineteen universities—most of whom were members of the BCS conferences—had profitable athletic programs, and the median net revenues over expenses were $4.29 million in 2006, excluding institutional support. The remaining 100 schools in Division I-A lost money, with a median negative net revenue of $8.92 million, excluding institutional support. Overall, then, the gap between the median positive net revenues and the median negative net revenues was $13.2 million in 2006, approximately $2 million more than the gap in 2004. The median member of NCAA Division I-A lost $7.27 million in 2006. A closer look behind these numbers is warranted.

In 2006, the median institution in Division I-A fielded 19 teams, the median institution in Division I-AA fielded 18 teams, and the median institution in Division I-AAA, which does not have football teams, fielded 16 teams. However, the only sports that generate net revenues over expenses at almost all of these schools are football and men’s basketball, with a handful of schools also able to run profitable programs in regionally popular sports such as ice hockey, women’s basketball, and wrestling. All of the other sports lose money. Thus, the football and men’s basketball programs must generate significant net revenues in order for the entire athletic program to operate profitably. Despite generating far less revenues than football programs, men’s basketball programs have a greater likelihood of profitability than football programs in both Division I-A and I-AA. Sixty-eight Division I-A men’s basketball programs made money in 2006, with a median profit of $2.72 million. Fifty-one teams lost money, with a median loss of $812,000. Overall, the 119 Division I-A men’s basketball programs had median generated revenues of $3.98 million, with median expenses of $3.06 million in 2006. The median program profited $1.58 million.

The vast majority of the Division I-AA men’s basketball programs lost money in 2006, with a median loss of $529,000 at these 108 institutions. Only 10 Division I-AA men’s basketball programs made money, with a median profit of $187,000. Overall, the median Division I-AA men’s basketball team lost $474,600. In Division I-AAA, 84 schools had a median loss of $774,000 in 2006, while 9 teams made a median profit of nearly $1 million. In total, the median I-AAA basketball program lost $639,600 in 2006.

As noted in the previous chapter, big-time college football is a potentially lucrative business. In 2006, 56% of Division I-A institutions realized this potential, earning a median profit of $8.8 million. It is safe to say that many of these 67 institutions were members of the BCS conferences. Conversely, 52 Division I-A football programs lost money, with a median deficit of $2.5 million. Overall, the median Division I-A football team profited by $5.35 million in 2006.

The financial story is much different in the off-Broadway world of Division I-AA football, where only five football programs generated even minimal profits in 2006. However, 113 Division I-AA football programs lost money, with a median deficit of $1.28 million. Overall, the median football program in Division I-AA lost $1.30 million in 2006.

Across all three levels of Division I athletics, several items are worth noting. First, average revenues and average expenses are both increasing, with expenses growing faster than revenues. Second, there is a continually increasing separation between the “haves” and “have-nots” of college sports. The schools that are making money are making more of it, and those that are losing money are losing more of it. Finally, between 16 and 19 of the 330 Division I institutions were profitable in any given year from 2004–2006. The remainder lost money.

Although Division I-A, I-AA, and I-AAA institutions compete against each other for NCAA championships in all sports other than football, it is this one-sport distinction that marks the difference between these levels of competition. In reality, Division I-A occupies an entirely different financial stratum than the others, with the median institution having approximately four times the amount of both total revenues and expenses. A brief discussion of the sources of revenues and operating expenses in college sports sheds additional light on these differences.

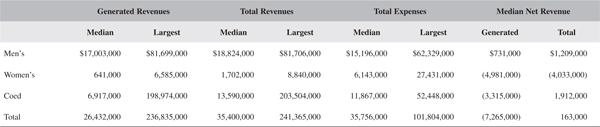

Ticket sales are the single largest source of revenue for Division I-A institutions, with the median school collecting $7.4 million in 2006. This is approximately 26 times the median amount earned in I-AA and 42 times the amount in I-AAA. Fundraising is the second most important revenue source, with the median I-A member bringing in $5.8 million in 2006, or approximately 9 times the amount in I-AA and 12 times the amount in I-AAA. The median athletic department in Division I-A receives 20% of its funding—$7.2 million per year—from the institution despite the fact that most are supposed to be auxiliary enterprises that are financially self-supporting. While the athletic departments in Divisions I-AA and I-AAA receive slightly less institutional support (a median amount of approximately $7.1 million in I-AA and $6.6 million in I-AAA in 2006), it constitutes over 70% of the total revenues at these schools. When looking at the overall profits or losses at any one NCAA member, it is appropriate to exclude institutional support from the revenue equation. Although it does represent the transfer of administrative funds to the athletic department from the institution, it does not represent monies that are otherwise earned by the institution because of the athletic department. Similarly, student activity fees provide Division I-A athletic departments with slightly more revenue than in I-AA or IAAA ($1.4 million versus $872,000 in I-AA and $511,000 in I-AAA) but constitute approximately 15% to 20% of the total revenues of the latter groups. Thus, the median Division I-AA and I-AAA schools receive over 70% of their revenue from their institutions and students, and are hardly self-sufficient. Table 1 shows net operating results excluding institutional support.

The various NCAA and conference distributions discussed in the previous chapter bring in much more revenue to the median institution in Division I-A ($4.87 million in 2006) than in Divisions I-AA and I-AAA ($395,000 and $232,000, respectively). Again, this is largely due to the dominance of the six power conferences. Finally, the median Division I-A school earns much more from broadcast rights ($168,000 in 2006), concessions, programs and novelties ($604,000), licensing royalties, advertising and sponsorships ($1.33 million), and miscellaneous items ($592,000) than does the median school in I-AA and I-AAA (approximately $257,000 and $252,000, respectively, for all of these items combined). Overall, the median Division I-A school had revenues of $35.4 million in 2006 (or $26.4 million when excluding institutional support), whereas the median Division I-AA and I-AAA institution had revenues of $9.64 million and $8.77 million, respectively (or $2.35 million and $1.83 million when excluding institutional support).

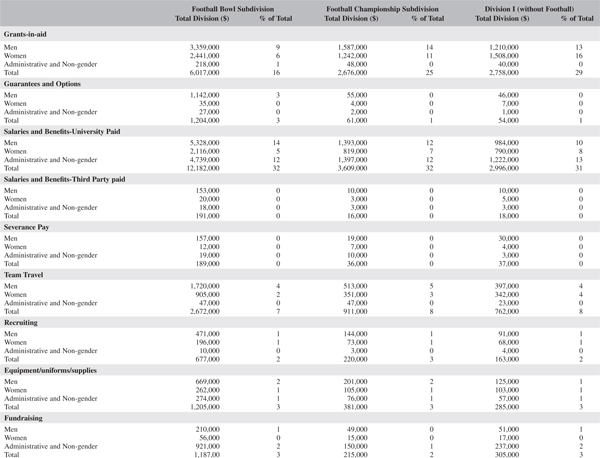

On the expense side of the ledger, the single greatest cost at all three levels of Division I is university paid staff salaries and benefits ($12.18 million in I-A, $3.61 million in I-AA, and $3.00 million in I-AAA). The second largest expense at all three levels is funding for athletic scholarships, on which the average Division I-A school spent $6.02 million, the average I-AA institution spent $2.88 million, and the average I-AAA school spent $2.76 million. Other average operating expenses which differed significantly between Division I-A and Divisions I-AA and I-AAA include team travel ($2.67 million versus $911,000 and $762,000); guarantees and options to visiting teams ($1.2 million versus $61,000 and $54,000); equipment, uniforms, and supplies ($1.2 million versus $381,000 and $285,000); fundraising ($1.2 million versus $215,000 and $305,000); severance pay ($189,000 versus $36,000 and $37,000); game expenses ($1.55 million versus $239,000 and $234,000); and recruiting ($677,000 versus $220,000 and $163,000).

Table 1 Net Operating Results (Medians)—Division I

| 2006 Median Values | |

| Football Bowl Subdivision | |

Total generated revenues | $26,432,000 |

Total expenses | $35,756,000 |

Median net generated revenue | ($7,265,000) |

| Football Championship Subdivision | |

Total generated revenues | $2,345,000 |

Total expenses | $9,485,000 |

Median net generated revenue | ($7,121,000) |

| Division I Without Football | |

Total generated revenues | $1,828,000 |

Total expenses | $8,918,000 |

Median net generated revenue | ($6,607,000) |

Source: Daniel Fulks, 2004–2006 NCAA Revenues and Expenses of Division I Intercollegiate Athletic Programs Report (2008). © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

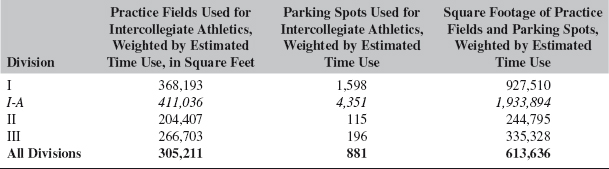

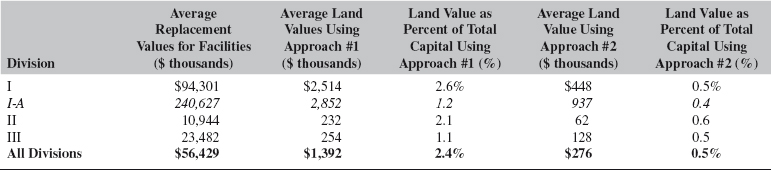

In addition to these differences in operating expenses, Division I-A institutions spend more on facilities maintenance and rentals ($5.2 million) than Division I-AA or I-AAA institutions ($594,000 and $365,000). Capital costs constitute a major aspect of total athletic expenditures and are not included in the aforementioned discussion. The NCAA funded study “The Physical Capital Stock Used in Collegiate Athletics” and a companion study “The Empirical Effects of Collegiate Athletics,” both excerpted in this chapter, detail the exorbitant spending on athletics-related facilities by Division I-A institutions and conclude that an “arms race” related to these facilities is occurring. This reflects the recent and still ongoing multibillion dollar spending spree on athletic facilities.

Overall, Division I-A athletic departments had median expenses of $35.8 million in 2006. The median expenses were $9.5 million in Division I-AA and $8.9 million in IAAA.

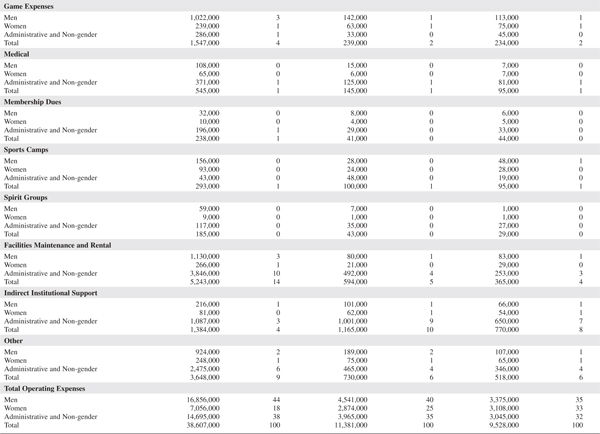

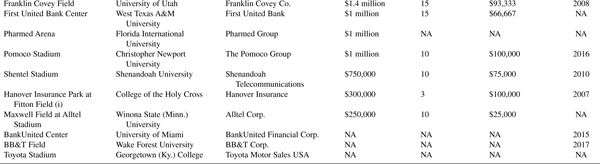

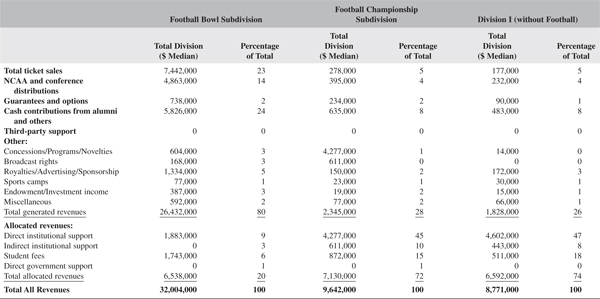

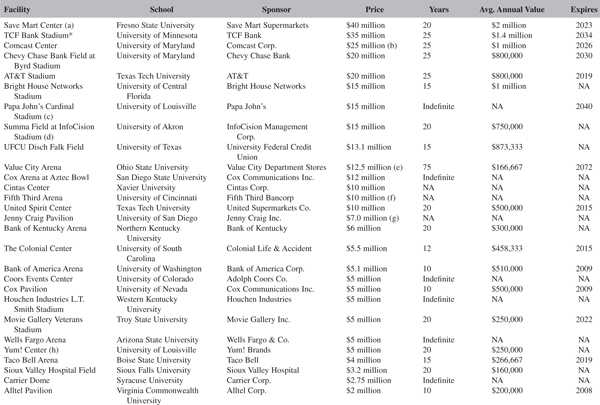

See Table 2 for a summary of revenues and expenses for 2006 for the Football Bowl Subdivision. Table 3 details sources of revenues for 2006 for the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision, the Football Championship Subdivision, and Division I (without football). Table 4 breaks down operating expenses for 2006 for the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision, the Football Championship Subdivision, and Division I (without football). Table 5 offers information on the naming-rights deals at various NCAA facilities.

Although the above analysis is certainly important, it must nonetheless be taken with a requisite grain of salt. Standard accounting techniques across NCAA institutions are lacking. In addition, related-party transactions involving other departments within the university are commonly used and some revenues and costs are improperly allocated across sports within the athletic department.

Former University of Michigan President James Duderstadt addresses these topics from both a macro and micro perspective, with a focus on Michigan’s athletic department in “Intercollegiate Athletics and the American University: A University President’s Perspective.” The review of the business of sports at the University of Michigan, one of the powerhouses of the industry and a member of the Big Ten conference, continues with a look at the athletic department’s internal budget documents for 2009–2010. Michigan’s profitability in intercollegiate athletics is the exception rather than the rule. In addition to gaining a university president’s thoughts, the findings of a Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics survey highlight another important campus constituency’s perceptions of college sports—those of the faculty.

The fairly bleak financial outlook for most intercollegiate athletics programs has led to an investigation of the indirect impacts of athletics on the institution. The athletic department is often the most visible aspect of the institution. As the front porch to the institutional house, it is important to attempt to know the impact of athletics on institutional fundraising, the size and quality of the student body, and the advertising and public relations of the institution. Anecdotal evidence suggests that these impacts can be substantial, as it has been at Butler University, Gonzaga University, St. Joseph’s University, George Mason University, and the University of Florida in recent years. However, Robert Frank finds that these impacts are very small, if existent at all, in his article “Challenging the Myth: A Review of the Links Among College Athletic Success, Student Quality and Donations” excerpted in this chapter. Pope and Pope examine the impact of success in major college football and men’s basketball on the number and quality of applications for admission to the institution. Stinson and Howard then review the impact of athletic success on fundraising at both the institution generally and in the athletic department more specifically.

The economics of college sports—both direct and indirect, actual and theoretical—often results in institutions making strategic decisions to change either their goals or the breadth and depth of their athletic programs. These decisions have broad consequences. The addition or subtraction of a team from an institution’s athletic offerings is usually spurred by programmatic, gender equity, and/or financial considerations. In the past decade, a number of institutions in pursuit of increased media attention and the big-money potential of college sports have upgraded their athletic departments to a higher NCAA division. Membership in NCAA Division I grew from 261 in 1980 to 330 in 2008–2009. The NCAA put a four-year moratorium in effect in 2007 on permitting institutions to join Division I or upgrade within Division I until 2011, though it did allow the 20 schools that were already in the process of upgrading their programs to proceed. Although there are some success stories, upgrading is typically a foolish endeavor; most schools are unprepared for the move and fail to be rewarded for it either financially or indirectly. The NCAA’s longitudinal study on the impact of upgrading the athletic program on the institution provides the details.

Many athletic departments have found that it is more efficient for them to outsource their marketing and other business operations to one of a handful of third-party providers that specialize in handling these affairs. The excerpt from Burden and Li examines the outsourcing of intercollegiate athletics programs.

As per the Internal Revenue Code, universities are nonprofit entities that are generally tax-exempt. As a consequence, the revenues that university athletic departments receive are not taxed either, despite the profit-motive of Division I members. An important consequence of this favorable tax treatment is that institutions that build or renovate athletic facilities are usually eligible for tax-exempt bonds to help fund these projects, and the lower interest rate allows them to maintain substantially lower debt service than if they were otherwise ineligible for this treatment.

Table 2 Summary of Revenues and Expenses (By Gender), Football Bowl Subdivision, 2006 Generated Revenues

Source: Daniel Fulks, 2004–2006 NCAA Revenues and Expenses of Division I Intercollegiate Athletic Programs Report (2008). © National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2008–2010. All rights reserved.

Notes: Generated revenues are produced by the athletics department and include ticket sales, radio and television receipts, alumni contributions, guarantees, and other revenue sources that are not dependent on entities outside the athletics department.

Total revenues, or allocated revenues, are composed of:

• Student fees directly allocated to athletics;

• Direct institutional support, which are financial transfers directly from the general fund to athletics;

• Indirect institutional support, such as the payment of utilities, maintenance, support salaries, etc. by the institution on behalf of athletics; and

• Direct governmental support—the receipt of funds from state and local governmental agencies that are designated for athletics

Table 3 Sources of Revenues, Division I Football Bowl Subdivision, Football Championship Subdivision, Division I (Without Football), 2006

Source: Daniel Fulks, 2004–2006 NCAA Revenues and Expenses of Division I Intercollegiate Athletic Programs Report (2008).

Notes: Generated revenues represent revenues earned by the athletics department and do not include allocated revenues. Allocated revenues include direct institutional support, indirect support, student fees, and governmental support.

Percentages are based on averages for entire subdivision.

Because of zero values reported by respondents, median values can be misleading.

Table 4 Operating Expenses by Object of Expenditure, Division I Football Bowl Subdivision, Football Championship Subdivision, Division I (without Football), 2006 Mean Values*

*Because of zero values reported by respondents, median values can be misleading. Consequently, mean values are provided in this table.

Source: Daniel Fulks, 2004–2006 NCAA Revenues and Expenses of Division I Intercollegiate Athletic Programs Report (2008).

Table 5 Naming-Rights Deals at NCAA Facilities (Listed by Total Value)

NA: Not applicable or not available

*Under construction or in late stages of development.

(a) PepsiCo acquired naming rights to the venue as part of a 23-year, $40 million sponsorship - the first three years of which came while the arena was under construction – but passed the rights to Modesto, California-based Save Mart Supermarkets while retaining campuswide pouring rights. Save Mart declined to disclose its contribution for the naming-rights portion of the deal.

(b) To be paid over 10 years; additional cost of $5 million included for logo rights to the basketball floor by Comcast.

(c) In August 2007, a $10 million pledge toward Papa John’s Cardinal Stadium expansion from Papa John’s International and its founder, John Schnatter, extended the previous deal worth $5 million.

(d) Field title sponsorship by Summa Health System worth $5 million over 20 years.

(e) Value City Arena was part of the naming-rights deal for the Jerome Schottenstein Center.

(f) Fifth Third’s naming rights to the university was part of a $10 million gift to the university that includes areas other than sports.

(g) Part of an overall $10 million gift to the university.

(h) The Yum! Center is the training facility for the University of Louisville.

(i) The stadium is owned by College of the Holy Cross and serves as home to that school’s baseball team. However, the Worcester Tornadoes brokered and receive all revenue from the naming-rights deal, and Holy Cross refers to the facility as Fitton Field.

Source:Research by David Broughton, Street & Smith’s SportsBusiness Journal. Used with permission.

This not-for-profit status is quite favorable for alumni and boosters making contributions to the athletic department because their donations are fully tax-deductible. When the donation is a prerequisite to the purchase of season tickets or luxury seating, it is still 80% tax-deductible. This makes donating to colleges and universities an even more attractive option for alumni and boosters, and allows athletic departments to generate substantial amounts of revenues from fundraising. The median member of Division I-A brought in $5.8 million in cash donations in 2006, while the median Division I-AA and I-AAA institutions collected $635,000 and $483,000, respectively. Collectively, the members of Division I-A received nearly $845 million in tax-free donations in 2005, most of which was tax-deductible for the donors.1 As this represents forsaken taxable income, it is fair to conclude that the federal government lost hundreds of millions in uncollected taxes—and thus implicitly subsidizes the college sports industry. The tax issues surrounding college athletics are further discussed in the Congressional Budget Office’s report on the topic.

Notes

1. Myles Brand, Letter to William Thomas, Chairman, U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means, Nov. 13, 2006, available at http://www.ncaa.org/wps/wcm/connect/2fa84c004e0d90aea0caf01ad6fc8b25/20061115_response_to_housecommitteeonwaysandmeans.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=2fa84c004e0d90aea0caf01ad6fc8b25.

OVERVIEW OF INSTITUTIONAL IMPACT

INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS AND THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY: A UNIVERSITY PRESIDENT’S PERSPECTIVE

James J. Duderstadt

The sports media fuel the belief that money is the root of all evil in college athletics. And, indeed, the size of the broadcasting contracts for college football and basketball events, the compensation of celebrity coaches, and the professional contracts dangled in front of star athletes make it clear that money does govern many aspects of intercollegiate athletics.

For example, Michigan, along with many other universities with big-time athletics, claims that football is a major money-maker. In fact, Michigan boasted that it made a profit of $14 million from its football program in 1997, the year it won the national championship…. Yet at the same time, most athletic departments plead poverty when confronted with demands that they increase varsity opportunities for women or financial aid for student-athletes. In fact, many athletic departments in Division I-A will actually admit that when all the revenues and expenses are totaled up, they actually lose money.

What is going on here? Could it be that those reporting about the economics of college sports have difficulty understanding the Byzantine financial statements of athletic departments? Are accounting tricks used to hide the true costs of intercollegiate athletics? Or perhaps those who lead and manage college sports have limited understanding of how financial management and business accounting works in the first place?

It is probably all of the above, combined with the many other myths about the financing of college sports, which confuse not only outsiders such as the press and the public, but even those insiders such as the university administration, athletic directors, and coaches. Before we dive into a discussion of how college athletics are financed these days, I want to straighten out several of the more common misperceptions.

STRIPPING AWAY THE MYTHS

First, most members of the public, the sports press, and even many faculty members believe that colleges make lots of money from sports. In reality, essentially all of the revenue generated by sports is used by athletic departments to finance their own operations. Indeed, very few intercollegiate athletics programs manage to balance their operating budgets. The revenue from gate receipts, broadcasting rights, postseason play, licensing, and other commercial ventures is rarely sufficient to cover the full costs of the programs. Most universities rely on additional subsidies from student fees, booster donations, or even state appropriations. Beyond that, college sports benefit from a tax-exempt status on operations and donations that represents a very considerable public subsidy.

The University of Michigan provides an interesting case study of the financing of intercollegiate athletics, since it is one of only a handful of institutions that usually manages to generate sufficient revenue to support the cost of operations (although not the full capital costs) for its intercollegiate athletics programs. Even for Michigan, financing intercollegiate athletics remains an ongoing challenge. For example, during the 1988–89 fiscal year, my first year as president, the University of Michigan won the Big Ten football championship, the Rose Bowl, and the NCAA basketball championship. The university also appeared in seven national football telecasts and dozens of basketball telecasts, played in a football stadium averaging 105,000 spectators a game, and sold out most of its basketball and hockey events. Yet it barely managed to break even that year, with a net profit on operations of about $1 million on $35 million of revenue….

When I was provost, football coach Bo Schembechler once complained to me about the enormous pressures to keep Michigan Stadium filled. He pointed to the losses that we would face if stadium attendance dropped 10 percent. I responded that, while this loss would be significant, it paled in comparison to the loss we would experience with a 10 percent drop in bed occupancy in the University of Michigan hospitals, which have an income more than twenty times larger than that of Michigan football…. Even football revenue has to be placed in perspective.

The University of Michigan, as one of the nation’s most successful athletics programs, generates one of the highest levels of gross revenue in intercollegiate athletics. Despite this fact, in some years, the expenditures of our athletic department actually exceed revenues…. This paradox is due, in part, to the unique “business culture” of intercollegiate athletics. The competitive nature of intercollegiate athletics leads most athletic departments to focus far more attention on generating revenue than on managing costs. There is a widespread belief in college sports that the team that spends the most wins the most, and that no expenses are unreasonable if they might enhance the success of a program. A fancy press box in the stadium? First-class travel and accommodations for the team? A million-dollar contract for the coach? Sure, if it will help us win! Furthermore, the financing of intercollegiate athletics is also complicated by the fact that while costs such as staff salaries, student-athlete financial aid, and facilities maintenance are usually fixed, revenues are highly variable. In fact, in a given year, only television revenue for regular events is predictable. All other revenue streams, such as gate receipts, bowl or NCAA tournament income, licensing revenue, and private gifts, are highly variable. While some revenues such as gate receipts can be accurately predicted, particularly when season tickets sales are significant, others such as licensing and private giving are quite volatile. Yet many athletic departments (including Michigan, of late) build these speculative revenues into annual budgets that sometimes crash and burn in serious deficits when these revenues fail to materialize.

Needless to say, this business philosophy would rapidly lead to bankruptcy in the corporate world. It has become increasingly clear that until athletic departments begin to operate with as much of an eye on expenditures as revenues, universities will continue to lose increasing amounts of money in their athletic activities, no matter how lucrative the television or licensing contracts they may negotiate.

Well, even if athletic departments essentially spend every dollar they generate, don’t winning programs motivate alumni to make contributions to the university? To be sure, some alumni are certainly motivated to give money to the university while (and, perhaps, only when) basking in the glow of winning athletic programs. But, many of these loyal alumni and friends give only to athletic programs and not to the university more generally. And the amounts they give are relatively modest….

University fundraising staff have known for many years that the most valuable support of a university generally comes from alumni and friends who identify with the academic programs of the university, not its athletic prowess. In fact, many of the university’s most generous donors care little about its athletic success and are sometimes alienated by the attention given to winning athletics programs.

The staggering sums involved in television contracts, such as the $6 billion contract with CBS for televising the NCAA tournament, suggest that television revenue is the goose that lays the golden eggs for intercollegiate athletics. But for most institutions, ticket sales are still the primary source of revenue. Indeed, there is some evidence that television can have a negative impact on the overall revenues of many athletic programs by overexposing athletic events and eroding gate receipts. Lower game attendance brought on by television has been particularly harmful to those institutions and conferences whose sports programs are not broadcast as primetime or national events, since many of their fans stay home from university events in order to watch televised events involving major athletic powers.

The additional costs required to mount “TV quality” events tend to track increasing revenue in such a way that the more one is televised, the more one must spend. More and more institutions are beginning to realize that there is little financial incentive for excessive television coverage. While exposure can convey the good news of successful athletic programs and promote the university’s visibility, it can also convey “bad news,” particularly if there is a major scandal or a mishap with an event.

If the financial and publicity impact of television is not necessarily positive, why is there then such a mad rush on the part of athletics programs for more and more television exposure? Speaking from the perspective of one of the most heavily televised universities in the country, my suspicion is that the pressure for such excessive television coverage is not coming from the most successful and most heavily televised institutions—the Michigans, Ohio States, and UCLAs. It is, instead, coming from the “have-not” institutions, those who have chosen not to mount competitive programs but who have become heavily dependent on sharing the television revenue generated by the big box office events through conference or NCAA agreements.

Stated more bluntly, the television revenue-sharing policies of many conferences or broader associations, such as the NCAA, while implemented with the aim of achieving equity, are failing. They are, in reality, having the perverse effect of providing strong incentives for those institutions that are not attractive television draws to drive the system toward excessive commercialization or exposure of popular events. While the have-not universities share in the revenues, these institutions do not bear the financial burden or disruption of providing television-quality events. In a sense, the revenue-sharing system does not allow for negative feedback that might lead to more moderate approaches to television broadcasting.

What about the suggestion that student-athletes deserve some share of the spoils? The argument usually runs as follows: College sports is golden—witness, for example, the $550 million paid each year by CBS for the NCAA tournament or the … payout per team for the football Bowl Championship Series games. And yet the athletes do not even get pocket money…. And what about college coaches, some of whom make over a million dollars a year? Shouldn’t we pay the athletes who generate all this money? Late in his long tenure as executive director of the NCAA, Walter Byers argued that since colleges were exploiting the talents of their student-athletes, they deserved the same access to the free market as coaches. He suggested letting them endorse products, with the resulting income going into a trust fund that would become available only after they graduated or completed their eligibility.2

These myths are firmly entrenched not only in the public’s mind but in the culture of the university. We need now to separate out the reality from the myth, to better understand the real nature of the financial issues facing college sports.

Reality 1: What Do Universities Really Make from Athletics?

As we noted earlier, in 1997, the University of Michigan generated $45 million from its athletics activities, of which only about $3 million came from television. Although the university actually generated far more than this from the broadcasting of events such as football and basketball games, the Rose Bowl, and the Big Ten and NCAA basketball tournaments, most of this revenue was shared with the other Big Ten and NCAA schools. How much of this revenue can we attribute to the efforts of students? This is hard to estimate. On the one hand, we might simply divide the entire revenue base by the number of varsity athletes (seven hundred) to arrive at about $45,000 per athlete. But, of course, coaches and staff also are responsible for generating revenue, by building winning sports programs or marketing or licensing sports apparel. Certain unusual assets, like Michigan Stadium, attract sizable crowds and generate significant revenue regardless of how successful the team is. Finally, we have not said anything yet about expenses. Operating expenditures at Michigan, as at every other university in the nation, are sometimes larger than revenues. As a result, the net revenues, the profit, is zero! While it is admittedly very difficult to estimate just how much income student-athletes bring to the university, it is clear that it is far less than most sportswriters believe.

Reality 2: What Do the Players Receive from the University?

At Michigan the typical instructional cost (not “price” or tuition) of our undergraduate programs is about $20,000 per student per year. When we add to this support for room and board and incidentals, it amounts to an investment of about $30,000 per year per fully tendered student-athlete, or between $120,000 to $150,000 per athlete over four or five years of studies. The actual value of this education is far higher, since it provides the student-athlete with an earning capacity far beyond that of a high school education (and even far beyond that of most professional sports careers, with the exception of only the greatest superstars). Of course, only a few student-athletes will ever achieve high-paying careers in professional sports. Most do not make the pros, and most of those who do are only modestly compensated for a few short years.

The real reward for student-athletes is, of course, a college education. Despite having somewhat poorer high school records, test scores, and preparation for college, athletes tended to graduate at rates quite comparable to those of other students. The reasons for their academic success involved both their strong financial support through scholarships and their academic support and encouragement through programs not available to students at large. Yet it is also the case that recruiting college athletes based entirely on physical skills rather than academic promise undermines this premise. As William Dowling, professor at Rutgers, has noted, “Problems will remain as long as players in the so-called revenue sports represent a bogus category of students, recruited on the basis of physical skills rather than for academic or intellectual ability.”4

Those who call for professionalizing college athletics by paying student-athletes—and they are generally members of the sports media—are approaching college sports as show business, not as part of an academic enterprise. Only in show business do the stars make such grossly distorted amounts. In academics, the Nobel Prize winner does not make much more than any other faculty member. In the corporate world, the inventor of a device that earns a corporation millions of dollars will receive only a small incentive payment for her or his discovery. The moral of the story is that one simply cannot apply the perverse reward system of the entertainment industry to college sports—unless, of course, you believe college sports is, in reality, simply another form of show business.

A PRIMER ON COLLEGE SPORTS FINANCING

Most business executives would find the financial culture of intercollegiate athletics bizarre indeed. To be sure, there are considerable opportunities for revenue from college sports…. In terms of their revenue-generating capacity, three college football teams, Michigan, Notre Dame, and Florida, are more valuable than most professional football franchises.5 Such statistics have lured college after college into big-time athletics, motivating them to make the investment in stadiums, coaching staffs, [and] scholarships, to join the big boys in NCAA’s Division I-A.

Yet most intercollegiate athletics programs at most colleges and universities require some subsidy from general university resources such as tuition or state appropriation. Put another way, most college athletics programs actually lose money…. And, while football coaches might like to suggest that the costs of “nonrevenue” sports are the problem, particularly those women’s sports programs mandated by Title IX, before blaming others, they should first look in a mirror. While football generates most of the revenue for intercollegiate athletics, it also is responsible for most of the growth in costs. More precisely, when college sports is transformed into an entertainment industry, and when its already intensely competitive ethos begins to equate expenditure with winning, one inevitably winds up with a culture that attempts to spend every dollar that it is generated, and then some.

Stated another way, the costs of intercollegiate athletics within a given institution are driven by decisions concerning the level of competition (e.g., NCAA Division, regional, or nationally competitive), the desire for competitive success, and the breadth of programs. Although football generates most of the revenue for big time athletic programs through gate receipts and broadcasting, it is also an extremely expensive sport. Not only does it involve an unusually large number of participants and attendant coaching and support staff, but the capital facilities costs of football stadiums, practice facilities, and training facilities are very high. Furthermore, many of the remaining costs of the athletic department, such as marketing staff, media relations, and business are driven, in reality, primarily by the needs of the football program rather than the other varsity sports. In this sense, football coaches to the contrary, big-time football programs are, in reality, cost drivers rather than revenue centers.

It is instructive to take a more detailed look at the various revenue streams and costs associated with intercollegiate athletics in order to get a sense of scale. The following are the principal sources of revenues and expenditures:

Revenues

• Ticket sales

• Guarantees

• Payouts from bowl games and tournaments

• Television

• Corporate sponsorships, advertising, licensing

• Unearned revenues

• Booster club donations

• Student fees and assessments

• State or other government support

• Hidden university subsidies

Expenditures

• Salaries

• Athletic scholarships

• Travel and recruiting

• Equipment, supplies, medicine

• Insurance

• Legal, public relations, administrative

• Capital expenditures (debt service and maintenance)

Furthermore, intercollegiate athletics is highly capital intensive, particularly at a big-time program such as Michigan. Few athletics programs amortize these capital costs in a realistic fashion. Including these imbedded capital costs on the balance sheet would quickly push even the most successful programs far into the red.

To illustrate, let us walk through the budget of the University of Michigan Department of Intercollegiate Athletics. First let me note that it is the practice of the university that intercollegiate athletics be a self-supporting enterprise, not consuming university resources. It receives neither state appropriation nor student tuition. Furthermore, this financial firewall works in both directions: any revenue balance earned by the athletic department cannot, under normal circumstances, be transferred to the academic side of the university. They must pay for what they cost the university, and they keep what they make….

Not included in these figures were onetime expenditures of roughly $18 million to expand Michigan Stadium, to decorate it with a gaudy maize-and-blue halo designed by the noted architect Robert Venturi, complete with the ten-foot-high words to the Michigan fight song, “Hail to the Conquering Heroes”; to install $8 million worth of “Jumbo-tron” television scoreboards; and to build a sophisticated control room for Internet broadcasts. These onetime expenses were charged against (and largely decimated) the flexible reserve funds of the department. Lest you think these latter expenses were unusually extravagant, Ohio State is in the midst of several construction projects that will leave their athletic department saddled with a $277 million debt, to be paid over the next thirty years. (And you wonder why people believe that the financial culture of intercollegiate athletics is wacko?)

As I noted earlier, the financial strategy in intercollegiate athletics is strongly driven by competitive pressures. The belief that those who spend the most win the most drives institutions to generate and spend more and more dollars. The prosperous programs at institutions such as Michigan, Penn State, and Notre Dame set the pace for the entire intercollegiate athletics enterprise, no matter what the size of the school. As expenditures on athletics programs continue to spiral out of control, there have been increasing calls for action at both the national and conference level. Yet part of the problem is that many athletic departments hide the true nature of the financial operations not only from the prying eyes of the press and the public, but even from their own universities. Several years ago, the Big Ten Conference launched an effort to contain costs by restricting the growth of institutional expenditures on athletics to the rate of inflation. At that time, many universities were suffering as their athletics revenues were insufficient to cover costs. There were also concerns about competitiveness, since the wealthier schools tended to dominate most Big Ten sports, particularly football.

More specifically, Michigan and Ohio State, because of their very large stadiums, had considerably more gate receipt revenue than the other Big Ten members. Onetime football powers such as Wisconsin and Minnesota had fallen on hard times, with mediocre teams and low stadium attendance. Minnesota was in a particularly difficult bind since it had shifted its football games to the downtown Minneapolis Metrodome and torn down its on-campus stadium. Earlier attempts to address this discrepancy among institutions through revenue-sharing formulas had finally become burdensome enough to the larger stadium schools, particularly with the entry of Penn State that the conference agreed to accept a more equitable formula.

Therefore, attempts to control expenditures rather than to redistribute revenues became the focus. But there was a big problem here. Nobody really knew how much the athletic departments in each university were spending. On top of that, no one seemed to know how much or where the revenue came from. And because most athletics programs were independent of the usual financial management and controls of their institutions, it was clear that this comparative information would be difficult if not impossible to obtain through the departments themselves.

Member institutions decided to form a special subcommittee to the Big Ten Council of Presidents comprised of the universities’ chief financial officers. This CFO committee was charged with developing a system to obtain and compare annual athletics revenues and expenditures within the Big Ten. Needless to say, this decision to go outside of the athletic enterprise for supervision did not go down well in some schools where the athletic department had unusual autonomy. And while opening their books for examination was not particularly troublesome to most Big Ten universities, since as public institutions they frequently had to endure audits from state government, this was a very sensitive matter to the one private university in the Big Ten, Northwestern.

The first set of comparisons across all universities was eye opening.8 Among the factors of particular note was the distribution of revenues.

Ticket sales | 38 percent |

Television and radio | 13 |

Gift income | 13 |

Subsidies | 11 |

Licensing, concessions, etc. | 9 |

Game settlements, guarantees | 8 |

Bowls and NCAA revenue | 4 |

Miscellaneous | 4 |

Although broadcasting and bowl revenues were important—and are becoming more so—the largest single revenue source (38 percent) remained gate receipts. This explains why the three universities with very large stadiums (Michigan at 105,000, Ohio State at 98,000, and Penn State at 96,000) stand out in revenues. Among the public universities, there was great disparity in the capacity to generate private support for athletics (with Michigan ranking, surprisingly enough, toward the bottom of the range) and in their subsidies from state support.

The financial studies revealed that 72 percent of total athletic department revenue is attributable to football. Another 23 percent comes from men’s basketball. In other words, 95 percent is generated by football and basketball combined. (Ice hockey contributes 4 percent and women’s basketball 1 percent.) A further breakdown of revenue sources shows the difference between men’s and women’s sports.

Men’s sports | 71.1 percent |

Women’s sports | 4.3 |

Administrative operations | 24.6 |

In terms of expenditures, 57 percent was spent on football and men’s basketball, while 24 percent was spent on women’s sports, and 14 percent on all other men’s sports. Despite the Big Ten Conference’s efforts to achieve gender equity, women’s programs amounted to only one-quarter of expenditures in the 1990s. Financial aid was distributed 67 percent to men, 33 percent to women, roughly in proportion to their representation among varsity athletes.

Two universities stood out in terms of the breadth and comprehensiveness of their programs: Ohio State, with thirty-five programs, and Penn State with thirty. Michigan’s twenty-three programs were only in the middle of the pack, despite the fact that Michigan ranked number one in revenues….

There was a factor-of-two difference in athletic department revenues and expenditures, ranging from Michigan and Ohio State … to Northwestern and Purdue…. The analysis also quickly made apparent why Northwestern had been so reluctant to share its financial data. In sharp contrast to the public universities, Northwestern was subsidizing its athletics programs from general academic resources to the tune of about $8 million per year (almost half their revenues). Although today, after two Big Ten football championships, faculty and students might believe it was worth the roughly eight hundred dollars per student of tuition (or other academic income) it cost to remain in the Big Ten, at the time of the first CFO surveys, this was highly sensitive information. While Northwestern’s hidden subsidy was the largest among Big Ten universities, it was certainly not unique. Some institutions provided hidden subsidies by waiving tuition or granting instate tuition rates for student athletes. Others received direct subsidies for their athletics programs through state appropriations (e.g., Wisconsin received $634,000 per year).

There were a number of other significant differences among the expenditure patterns of the various universities. For example, several of the public universities charged only in-state tuition to athletes, even if they were out-of-state residents, thereby reducing very significantly their costs for athletic scholarships. In contrast, Michigan charged full out-of-state tuition levels, which were comparable to those of private institutions, thereby driving up the costs of athletic grants-in-aid programs considerably. Labor costs also varied widely among institutions, ranging from urban and unionized wage scales to rural and nonunionized wage scales.

It was finally concluded, after several years of effort, that the great diversity among institutions in terms of the manner in which revenue was generated, expenditures were managed, and accounting was performed made it almost impossible to attempt conference-wide cost containment. Hence, the Big Ten presidents adopted a policy encouraging rather than requiring cost containment. However, they also decided to continue the annual CFO comparative analysis of revenues and expenditures, if only to provide visibility for unusual practices.

SHOW ME THE MONEY!

Revenue flows into athletics departments from a number of sources and out again through a complex array of expenditures…. In this brief discussion, I will focus only on a few items of particular interest.

One of the most expensive elements of sports is the current grants-in-aid system for the financial support of student-athletes. In contrast to the need-based financial aid programs for regular students, colleges are allowed to provide student-athletes with sufficient support to meet “all commonly accepted educational expenses”—a full ride, regardless of financial need or academic ability. This policy, first implemented in football in the 1950s, has spread rapidly to all varsity sports. As the costs of a college education have rapidly increased over the past two decades, the costs of grants-in-aid have risen dramatically…. But there is considerable variation among institutions ….

In some cases, this discrepancy is due to institutions that choose to subsidize financial aid by granting all athletes in-state tuition levels, in effect hiding the subsidy of the difference between in-state and out-of-state levels. Although some universities restrict the number or types of grants-inaid they provide in various sports, the University of Michigan has long had a policy of fully funding all allowable grants-in-aid in all sports in which it competes. Since most student-athletes are subject to out-of-state tuition levels, the resulting cost of athletically related student aid is unusually high ….

A second factor in the inflating costs was the rapid growth in size of football programs as coaches pushed through the unlimited-substitution rules in the 1960s. This system allowed college football to develop specialists for essentially every position and every situation in the game—offense and defense, blocking and tackling, kicking and passing. Although it was promoted as a way to make the game more exciting, it was not just a coincidence that it also made football far easier to play and to coach. More significantly, it transformed college football into a corporate and bureaucratic enterprise, with teams of over one hundred players, dozens of coaches, trainers, and equipment managers, and even technology experts in areas such as video production and computer analysis. Furthermore, unlimited substitution not only transformed college football into the professional football paradigm, but it also demanded that high school football follow the colleges and the pros down the same expensive path.

The third factor driving the rapid expansion of the program’s cost and complexity has been the insatiable desire of football coaches for any additional gimmicks that might provide a competitive edge, either in play or competition. Special residences for football players became common, some resembling country clubs more than campus dormitories. Many football programs have built not only special training facilities but also even museums to display their winning traditions to prospective recruits…. Teams usually travel in high style, with charter jet service, four-star hotels, and even special travel clothing such as team blazers. And, of course, each time a coach at one university dreams up a new wrinkle, all of the other coaches at competing universities have to have it, no matter how extravagant or expensive.

This competitive pressure from coaches and fans—and even the media—has made it very difficult for athletic departments to control costs. Each time actions are proposed to slow the escalation of costs in the two main revenue sports, football and basketball, they are countered with the argument that the more one spends, the more one will win and hence the more one will make. The relative financial inexperience of those who manage athletic departments makes it even more difficult to resist these competitive forces. They tend to develop a one-dimensional financial culture, in which all attention is focused on revenue generation, and cost controls are essentially ignored.

A conversation with any athletic director soon reveals just how much of their attention is devoted to generating revenue to cover ever-increasing costs. This preoccupation with revenue generation propagates up through the hierarchy, to university presidents and governing boards, athletic conferences, and even the NCAA. Far more time is spent on negotiating broadcasting contracts or licensing agreements than on cost containment, much less concern about the welfare of student-athletes or the proper role of college sports in a university.

Though most of the revenue for college sports has traditionally come from revenue associated with football and basketball events, several of the most popular programs have generated very extensive licensing income from the use of institutional logos and insignia. A number of major athletics programs, Michigan among them, have signed lucrative contracts with sports apparel companies. Many athletic departments have also launched extensive fundraising efforts involving alumni and fans, both for ongoing support and endowment. In fact, both athletic scholarship programs and key athletic department staff such as athletic directors and football coaches are supported by endowments in some universities.

Athletic departments go to great lengths and considerable creativity to find new sources of revenues. For example, when Michigan decided to replace its artificial turf in Michigan Stadium with natural turf in 1992, the athletic department got the bright idea that people might want to purchase a piece of the old carpet for nostalgic reasons. They chopped up the old artificial turf into an array of souvenirs, ranging from coasters to doormats to large rugs containing some of the lettering on the field. To their delight, these sold like hot-cakes, and the department made over two hundred thousand dollars….

Another example is the construction of an elegant new plaza and fence surrounding Michigan Stadium in 1995. The athletic department decided to sell paving bricks at a premium (one hundred to one thousand dollars apiece) and allow people to inscribe their names and perhaps even a brief message. Again, demand soared for the opportunity to become “a part of Michigan Stadium,” and the department rapidly raised the several hundred thousand dollars required for the project.

Licensing provides a more standard means for generating revenue for the athletic department. Michigan moved early into a more direct merchandising effort, placing retail shops (the M-Go Blue Shops) in various athletics venues, so that it could participate directly in the profits from athletic or signature apparel. It was always a fascinating experience to browse through these shops to see what the fertile creativity of the marketing side of the athletic department had devised or approved for licensing: maize-and-blue toilet seats that play “The Victors” when raised, the Michigan football helmet chip-and-dip bowl, and hundreds upon hundreds of different sweatshirt designs. The catalog mail-order business became particularly lucrative.

….

We have noted earlier the extreme volatility of most revenue sources for intercollegiate athletics. While a New Year’s Day bowl appearance or success in the NCAA Basketball Tournament can provide a windfall, a poor season can trigger rapid declines in gate receipts, licensing income, and private gifts. Catastrophe awaits the naive athletic director who builds an expenditure budget based on such speculative income, since disaster awaits when the books are finally closed at year end. During my tenure as president, we not only required the athletic department to budget very conservatively, but it also was encouraged to build a reserve fund with sufficient investment income to compensate for any uncertainty in the operating budget. In fact, our athletic director generally measured financial performance in terms of the growth of the reserve fund from year to year.

FINANCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY

The athletic department at most NCAA Division I-A universities is treated as an auxiliary activity, separated by a financial firewall from the budgets of academic programs. This strategy allows athletic directors to offer up the excuse that the sometimes flamboyant expenditures of the department are not being made at the expense of the university. But it also creates major problems. It tends to focus most of the athletic department’s energy (not to mention the conference’s and NCAA’s) on revenue generation rather than cost management. It subjects coaches and staff to extreme pressures to generate additional revenue in the mistaken belief that it will enhance the competitiveness of their programs. And, perhaps most significantly, it further widens the gap between the athletic department and the rest of the university.

Despite the boasts of athletic directors and football coaches to the contrary, intercollegiate athletics at most institutions—perhaps all institutions, if rigorous accounting principles were applied—is a net financial loser. All revenues go simply to support and in some cases expand the athletic empire, while many expenditures that amount to university subsidy are hidden by sloppy management or intricate accounting. Put more pointedly, college sports, including the celebrity compensation of coaches, the extravagant facilities, first-class travel and accommodations, VIP entertainment of the sports media, shoddy and wasteful management practices, all require subsidy by the university through devices such as student fees, hidden administrative overhead support, and student tuition waivers.

Yet our athletic departments not only tout their self-supporting status, but they vigorously seek and defend their administrative and financial independence. And well they should, since their primary activity is, increasingly, operating a commercial entertainment business. As college football and basketball become ever more commercial and professional, their claim on any subsidy from the university is diminished.

Of course, few of our sports problems are self-supporting. If we illuminate hidden costs and subsidies, we find that all intercollegiate athletics burden the university with considerable costs, some financial, some in terms of the attention required of university leadership, some in terms of the impact to the reputation and integrity of the university, and some measured only in the impact on students and staff. Experience has also shown that expenses always increase somewhat more rapidly than the revenues generated by college sports.

In conclusion, the mad race for fame and profits through intercollegiate athletics is clearly a fool’s quest. Recognition on the athletic field or court has little relevance to academic reputation. Nebraska can win all the national championships it wishes, and it will never catch fair Harvard’s eye. Indeed, fame in athletics is often paradoxical, since it can attract public scrutiny, which can then uncover violations and scandal. As the intensity and visibility of big-time athletics build, the university finds itself buffeted by the passion and energy of the media and the public, who identify with their athletics programs rather than their educational mission.

Yet every year, several more universities proudly proclaim they have decided to invest the resources to build sports programs that will earn them membership in NCAA’s Division I-A. Sometimes lessons are never learned.

Notes

….

2. Walter Byers with Charles Hammer, Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995.

….

4. William Dowling, “To Cleanse Colleges of Sports Corruption, End Recruiting Based on Physical Skills,” Chronicle of Higher Education, July 9, 1999, B9.

5. Richard Sheehan, Keeping Score: The Economics of Big-Time Sports, New York: Diamond Communications, 1996, chaps. 11, 12.

….

8. Athletic Operations Survey, 1993–94, Big Ten Conference, Chicago, 1994.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS OPERATING BUDGETS, 2009–2010

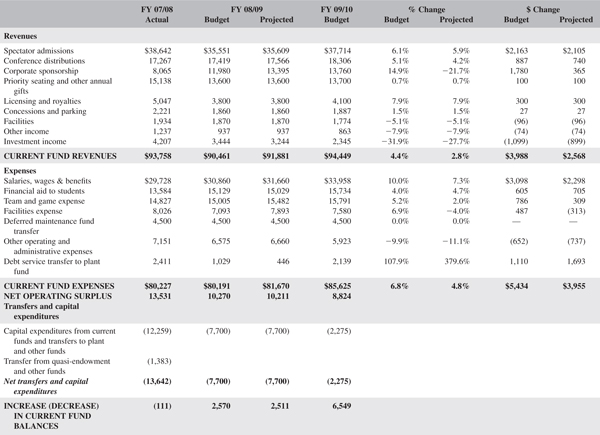

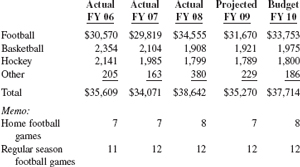

For the proposed FY 2010 Operating Budget (described in detail on the following pages), we project an operating surplus of $8.8 million based on operating revenues of $94.4 million and operating expenses of $85.6 million. The budgeted surplus will be added to our operating reserves. [Ed. Note: See Table 6.] Highlights are as follows:

• The budget reflects an eight-game home schedule for football (seven home games were played last year).

• Budgeted sponsorship revenue (including radio rights) has increased to $13.7 million from $8 million in FY 08. Sponsorship revenue includes the IMG and Adidas agreements, both of which became effective in FY 2009.

• Included in operating expenses is a $4.5 million transfer to a deferred maintenance fund established in FY 2003. The deferred maintenance fund is used as a means to provide for major repair and rehabilitation projects for our athletic facilities. We expect to continue to set aside additional funds in future years for this purpose.

• The budget reflects operating expenditure increases of 4.8% over projected operating expenses in FY 2009, principally due to compensation, financial aid, team travel, and home game expense increases.

We are also pleased to report that based on preliminary results, we project that the operating surplus for FY 09 will be $10.2 million, approximately the same as budgeted. The accumulation of operating surpluses will be used to fund our ongoing capital needs and facility renewal projects in FY 2010 and beyond.

….

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT 2009–2010 BUDGET NOTES AND ASSUMPTIONS (ALL DOLLAR AMOUNTS IN 000’S)

Basis for Accounting

The University of Michigan Athletic Department manages its financial activity through the use of three different funds, the Operating Fund, the Endowment Fund, and the Plant Fund.

The Operating Fund budget is presented herein. (A consolidated financial statement is prepared annually and audited by PricewaterhouseCoopers). The Operating Fund budget includes most of the revenues and expenditures of the Athletic Department, with the exception of Endowment Fund gifts and associated market value adjustments (which are recorded in the Endowment Fund), and investments in the physical plant (with the associated debt, which are recorded in the Plant Fund).

Table 6 Michigan Athletic Department FY 2010 Operating Budget (in thousands)

Source: University of Michigan. Athletic Department. Used with permission.

Governmental Accounting Standards Board Statement No. 33 (“GASB 33”) requires that the promises of private donations be recognized as receivables and revenues in the year the pledge was given, provided they are verifiable, measurable, and probable of collection. The Athletic Department Operating Fund budget presented herein records gifts when received (i.e., on a cash basis). The Operating Fund budget presented also reflects 100% of the gifts related to preferred seat donations (“PSD”) as gift income. For financial reporting purposes, 20% of PSD gifts are reflected in spectator admissions.

1. Spectator admissions

Spectator admissions are net of associated guarantee payments to visiting schools and consist of the following:

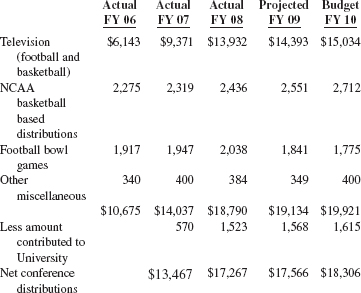

2. Conference distributions

Expected Big 10 conference distributions consist of the following:

3. Facilities

Facility income includes the fee and rental revenue from the University of Michigan Golf Course, the Varsity Tennis Center, Yost Ice Arena, and the various other athletic department facilities.

4. Investment Income

Investment income includes the return from the University Investment Pool (UIP) program as well as the quarterly distribution from Endowment and Quasi-Endowment Funds.

5. Other Income

Other income consists of guarantees received for hockey and basketball away games, ticket handling fees, and other miscellaneous income.

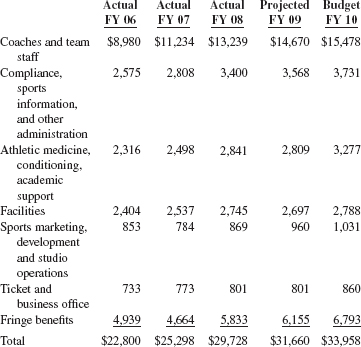

6. Compensation Expense

The athletic department has approximately 245 full time employees including those that have joint appointments with other University units, and various part time employees, interns, and graduate assistants. Compensation expense by area is as follows:

7. Financial aid to students

The athletic department grants the maximum allowable scholarships to all varsity sports. Total grant-in-aid equivalencies are approximately 335 with an estimated in-state to out-of-state ratio of 30%/70%.

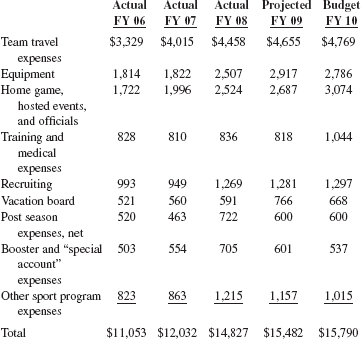

Sports program expense is comprised of the following:

Post season expenses are estimated based on the likelihood of participation in post season events for the majority of varsity sports. The post-season budget assumes that the football bowl expenditures will not exceed the bowl expense allowance received.

9. Facility Expenses

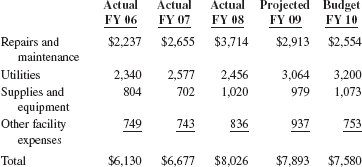

Facility expenses consist of the following:

10. Deferred Maintenance Fund Transfer

In 2002 the department established a Deferred Maintenance Fund as a means to provide for repair and rehabilitation projects for the athletic physical plant. Transfers from the Operating Fund to the Deferred Maintenance Fund are reflected as operating expenses in this presentation.

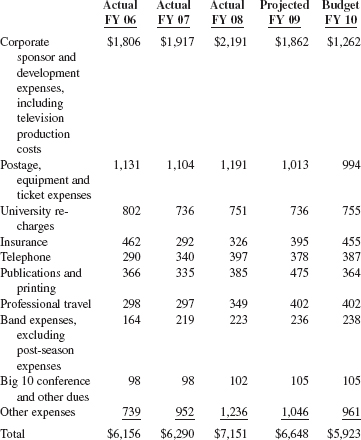

11. Other Operating and Administrative Expenses

Other operating and administrative expenses consist of the following:

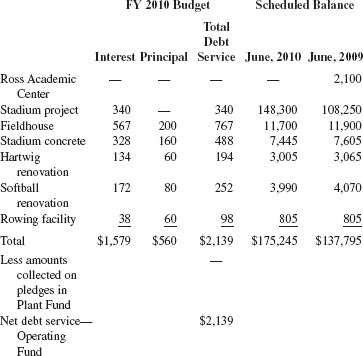

12. Debt Service

Debt service and associated debt is summarized as follows:

13. Transfers to Plant Fund for Capital Expenditures

Capital expenditures and estimated plant fund transfers are budgeted at $2.3 million for fiscal year 2010 and consist of various renovation projects.

FACULTY PERCEPTIONS OF INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS SURVEY, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, PREPARED FOR THE KNIGHT COMMISSION’S FACULTY SUMMIT ON INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS, OCT. 15, 2007

INTRODUCTION

In a national survey of more than 2,000 faculty members at universities with the country’s most visible athletic programs, a striking number of professors say they don’t know about and are disconnected from issues facing college sports. More than a third say they don’t know about many athletics program policies and practices, including the financial underpinnings of their campuses’ athletics programs. Furthermore, more than a third have no opinion about concerns raised by national faculty athletics reform groups. The largest portion of faculty (41 percent) believe faculty governance roles on campus associated with the oversight of intercollegiate athletics are ill defined, and most believe those roles are not particularly meaningful. On other issues, faculty are often equally divided between those who are satisfied with the conduct of their institution’s intercollegiate athletics programs and those who are not.

Faculty members do tend to agree on several key points:

• Athletics decisions on campus are being driven by the demands of the entertainment industry.

• Faculty members are dissatisfied with their roles in athletics governance on campus, although more of them are satisfied with presidential oversight of athletics on their own campuses.

• Salaries paid to head football and basketball coaches are excessive, and the financial needs of athletics get higher priority than academic needs. Still, half of the respondents also think athletics success results in financial gains to campus initiatives unrelated to sports.

• Professors have similar levels of satisfaction with the academic performance of students in general and athletes in sports other than football and basketball. However, they are significantly less satisfied with the academic performance of football and basketball players. They believe athletes are more burdened than other students by demands on their out-of-class time.

• Faculty members are satisfied with the practice of awarding scholarships based on athletics ability, and believe that scholarships for basketball and football athletes may not compensate them fairly for their services.

BACKGROUND

In 1989, the trustees of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation were concerned that highly visible athletics scandals threatened the integrity of higher education. They formed the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics to develop and win acceptance of realistic reforms that would close the widening chasm between higher education’s ideals and big-time college sports.

In its 1991 and 2001 reports, the Knight Commission called on university faculties to join other members of the academic community to act together to restore the balance of athletics and academics on campus. In meetings since that time, the Knight Commission has heard testimony from professors involved in campus leadership, athletics governance, and athletics reform groups such as the Coalition on Intercollegiate Athletics and the Drake Group.

Following the Knight Commission’s Summit on the Collegiate Athlete Experience in 2006, members of campus reform groups approached the Knight Commission to propose a summit on the role of the faculty in maintaining a healthy relationship between academics and athletics on campus. The commission agreed to host such a summit.

In preparation for the Faculty Summit, the Knight Commission asked Dr. Janet H. Lawrence, an associate professor at the University of Michigan’s Center for Postsecondary and Higher Education, to conduct a national survey of faculty members at NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (formerly Division I-A) universities. The purpose was to learn how faculty members who are most likely to have knowledge about athletics issues through university governance involvement, or faculty who are most likely to interact with athletes in the classroom, perceive a range of athletics issues. The findings are to be used as background for discussions at the summit as well as for further conversation that may follow within athletic conferences and on individual campuses. The survey was designed to answer the following questions:

• How do faculty perceive intercollegiate athletics on their campuses?

• How satisfied are they with the governance, academics and financial aspects of intercollegiate athletics?

• What most concerns them about intercollegiate athletics?

• What priority do they think campus faculty governance groups should give to intercollegiate athletics?

The survey took into account how perceptions might be affected by differences in faculty members’ career experiences, campus climate, athletics success, and athletes’ academic success. Finally, the study looked at the likelihood of individual professors agreeing to get involved in solving problems in intercollegiate athletics on their own campuses and whether they believed such activity would be effective.

The survey was sent to 13,604 faculty members at 23 institutions in the NCAA’s Football Bowl Subdivision (formerly known as Division I-A). Two institutions were randomly selected from each of the eleven Football Bowl Subdivision conferences and one was chosen from the institutions not affiliated with any conference. Among those surveyed were 1) faculty currently involved in university governance (e.g., faculty senates); 2) faculty in roles associated with intercollegiate athletics oversight (e.g., faculty athletics representatives, members of campus athletics advisory boards); and, 3) tenured or tenure track faculty who teach undergraduates and, as a result, have a high probability of interacting with athletes in the classroom. Researchers received 3,005 responses from professors at all 23 institutions surveyed. However, the final sample used in the analysis consisted of 2,071 responses after adjusting for those who did not fully complete the survey, faculty currently on sabbatical, emeritus faculty, non-tenure track faculty, and administrators inadvertently included.

The sample design did not attempt to approximate a random sample of faculty that could be generalized with a margin of error since it was important to focus on faculty with governance involvement. Of this purposive sample, more than three-quarters (78 percent) are involved in faculty governance at some level and 14 percent of this group has experience with athletics governance. Only 22 percent of the respondents report no current involvement in either athletics or campus-wide governance.

SURVEY RESULTS

The overarching finding is: A striking number of professors say they don’t know about and are disconnected from issues facing college sports. It’s all the more striking because the survey sample included faculty involved in governance or undergraduate teaching—those more likely to be informed about these issues.

More than a third of faculty members are unfamiliar with select policies and practices pertaining to athletics, the financial underpinnings of athletics on campus, or concerns raised by national faculty athletics reform groups. Perhaps as a result, this lack of information results in large segments of faculty members responding that they have no opinion about a number of academic, governance and financial issues. Those who say they are informed about such operations are divided among those who are satisfied with the conduct of intercollegiate athletics on their campus and those who are not. The large segment of uninformed faculty is particularly noteworthy because the sample was designed to include faculty involved in governance or undergraduate teaching and, as a result, would seem more likely than a randomly drawn sample of university faculty to be informed about these issues.

Concerning academic issues, more than half (53 percent) have no opinion about their satisfaction with coaches’ roles in the admissions process; nearly half (49 percent) do not know if a faculty committee on campus regularly monitors the educational soundness of athletes’ programs of study; 40 percent have no opinion about the academic standards on their campus that guide admissions decisions for athletes in football and basketball, and a similar portion (38 percent) have no opinion about the attention given by campus faculty governance groups to the quality of athletes’ educational experiences.

Regarding finances, 39 percent of faculty do not know if athletics programs on their own campuses are subsidized by institutional general funds. Also, nearly a third (31 percent) offer no opinion on whether they are satisfied or dissatisfied with the use of general funds to subsidize athletics on their campus—likely the result of a lack of information on which to base an opinion.

More than a third have no opinion about the types of roles faculty members play in the governance of intercollegiate athletics (35 percent) and the range of faculty perspectives considered by central administrators when institutional positions on athletics are formulated (34 percent).

While perceptions about and satisfaction with the conduct of intercollegiate athletics are mixed among faculty who do have knowledge of athletics operations, professors generally share the same beliefs about several key issues involving governance, academics, athlete welfare and finances. These shared beliefs include the following:

GOVERNANCE

1. Faculty members say they believe intercollegiate athletics is an auxiliary service and decisions are driven by the demands of the entertainment industry.

More than six in 10 (62 percent) say that intercollegiate athletics is structurally separate from the academic part of their university, and half say that decisions about the athletics program are driven by the entertainment industry with minimal regard for their university’s academic mission.

2. Although faculty are more satisfied than not with their respective president’s oversight of athletics, they are generally dissatisfied with their roles in faculty athletics governance and the consideration of faculty input on athletics decisions. However, when asked to prioritize issues for campus faculty governance groups, intercollegiate athletics ranks very low.

Faculty members are more satisfied (46 percent) than not (28 percent) with their respective president’s oversight of intercollegiate athletics. But more faculty (36 percent) than not (28 percent) are dissatisfied with faculty athletics governance roles. More specifically, the largest portion of the faculty (41 percent) believe faculty governance roles associated with the oversight of athletics on campus are ill defined; 32 percent disagree with that statement and 26 percent do not know. Even a third of those with athletics governance experience (35 percent) believe these roles are ill defined. Further, professors are generally dissatisfied with the extent to which faculty input is considered when athletics decisions are made, and are more dissatisfied (44 percent) than not (25 percent) with the range of faculty perspectives considered by administrators when athletics positions are formulated. Further, more respondents (47 percent) than not (28 percent) believe faculty members are interested in intercollegiate governance issues on their campus. However, they rank intercollegiate athletics second to last, just above Greek life, in a list of 13 priorities for campus faculty governance groups.

3. Faculty members involved in athletics governance are more positive about all aspects of intercollegiate athletics than those who are not involved.

ACADEMICS AND ATHLETE WELFARE