Busting the Boundaries

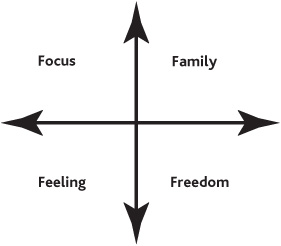

So what can a mentor do to set up an expansive, boundary-free learning environment? Extensive research shows that great mentors give unswerving attention to four essential components: focus, feeling, family, and freedom.

Focus

There are several ways adult learning (andragogy) is different from child learning (pedagogy). Adults are motivated to learn when they perceive an immediate or short-term rationale for that learning. You can tell a child, “This history you are learning in the classroom may not be useful on the playground at recess, but someday it will be helpful to you” and retain their interest. Adults are not so gullible. Granted, some adults get a kick out of learning purely for learning’s sake, but they are in the minority. Most adults are motivated to learn if the effort will have a clear payoff in the present or—at most—in the very near future.

The mentoring partnership must be conducted so that the protégé knows the purpose of the learning. There needs to be an “as a result of this learning, you will be able to …” component woven through your partnership. In the organizational context, it helps to anchor the learning to the unit or organizational vision or mission, to unit objectives, and to the protégé’s personal or professional goals and aspirations. The tie must be subtle … and at the same time obvious. It should be an initial focus … and a perpetual one. Anchoring learning to objectives is one way to create useful guide-posts for measuring success. Think of focus as not only the basis for your interaction but as the very language you speak.

Feeling

Do you remember what you learned about relationships when you were in high school? Remember that friendship that went sour and how you worked so hard to get it back together? Remember going steady, breaking up, having fights, making up … and on and on? The lessons learned in those heart-pain days seem indelibly etched in our memories. They are the lessons we teach our children, nieces or nephews, or friends’ children.

Now think about other things you learned in high school. Maybe you learned sine, cosine, and tangent. You learned to conjugate verbs and diagram sentences. You knew the length of the Amazon River, the height of the Empire State Building and could name the capital of every state in the union—including South Dakota and Kentucky! And you probably got A’s on those tests. Remember? If there were a pop quiz today, how would you fare? Somehow, most learning that is not anchored to the heart is not retained.

The mentoring relationship is at its best when it is conducted with spirit and emotion. Talk with someone who has served in a combat role in war. They can tell you intricate details of the conflicts but only vaguely about the time spent in training. The lessons learned in combat were lessons of the heart, imprinted with the passion of the most exhilarating highs and the most depressing lows. Part of the mentor’s job is to foster an environment where feelings, emotions, and learning are tightly linked.

Family

Mentoring works best when implemented in the spirit of partnership. In The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge talks about another’s “fellowship” as a key support for learning, but we think “family” is a better “f” word to capture the spirit of partnership. Fellowship could be simply an association, but “family” implies a much deeper relationship. Learning requires risk taking and experimentation. It necessitates error and mistake. It is uniquely difficult for a mentor to carry out an insight goal (fostering discovery) from an in-charge (I’m the boss) role. Even if the mentor is not in a functional managerial role, simply being an “expert” creates the potential of unequal power. Applied to mentor and protégé, “family” implies a close relationship, not a parent-child relationship. The goal is partnership.

Freedom

The ultimate test of the expansiveness of the mentoring relationship is when the learner is set free. Mentoring relationships are exercises in ceaseless letting go. Few conditions do a greater disservice to the protégé than mentor dependence. Dependence leads to protégé uncertainty and insecurity. Dependence results in a relationship that is inefficient and barren of worth to either mentor or protégé. Dependence implies the mentor is the sole repository of the wisdom required by the protégé.

Engendering freedom is all about creating strength and courage. Fostering freedom is also about building bridges to other resources, including linking the protégé up with other mentors. It means helping the protégé connect with a storehouse of resources to be accessed as needed.