Coordinating Improvement Through Hoshin Kanri

How should horizontally coordinated organizations ensure that the actions taken by its front-line employees are consistent with organizational goals?

—Gittell (2000, p. 101)

Just like any other defined task, coordination takes effort. Yet coordination is not just another task. Here are some important differences:

- Coordination is a requirement not in itself but because other tasks are required.

- Everyone, without exception, takes part in the coordination effort.

- Coordination has no product. Instead it serves to establish relationships between tasks and their products. Coordination has no independent purpose; it is a prerequisite for the accomplishment of other purposes.

Coordination, as we see, is a kind of “dynamic glue” that binds tasks together into larger, meaningful wholes.

This book focuses on the practices and tools of lean. So far different practices and tools have been outlined. This final chapter addresses one of the most important issues when implementing a Lean Work Design: How shall the different practices and tools be coordinated? In this context coordinated means that the tools and practices are used in a way that the goals of the company are realized.

The quotations above demonstrate how pervasive the problem of coordination is within an organization and that coordination means the parts are working together to accomplish the goals of the system. It is important to note that coordination efforts have to involve everyone in the organization. The coordination efforts cannot be delegated to one unit of a company.

Hoshin Kanri Background

The final tool discussed in this second part of the book is Hoshin Kanri or strategy deployment since it is a tool to achieve coordination between individual actions and the goals of the company. This is why it was called the “nervous system of lean production” by Dennis (2007, p. 124).

Hoshin Kanri is a multilevel strategic planning methodology based upon collective planning and implementation principles. Its objective is to link senior management’s goals to operational targets that allow for the realization of these goals. Hoshin Kanri and Total Quality Management (TQM) coevolved in Japanese firms starting in the 1950s, as executives sought to enhance their quality improvement efforts (Babich 2005; Witcher and Butterworth 1999). To improve the definition of their quality goals, Japanese firms first integrated the Deming Cycle (i.e., Plan-Do-Check-Act: PDCA) into their enterprise-wide planning system (Ishikawa 1990). Then, they adopted Drucker’s (1954) Management by Objectives to instill goal clarity into their quality systems. For example, the Deming Prize incorporated many Hoshin Kanri concepts into its checklist in 1958 (Jackson 2006). This adoption accelerated Hoshin Kanri diffusion throughout Japan as firms sought to imitate the winners (Babich 2005).

Key Phases of Hoshin Kanri

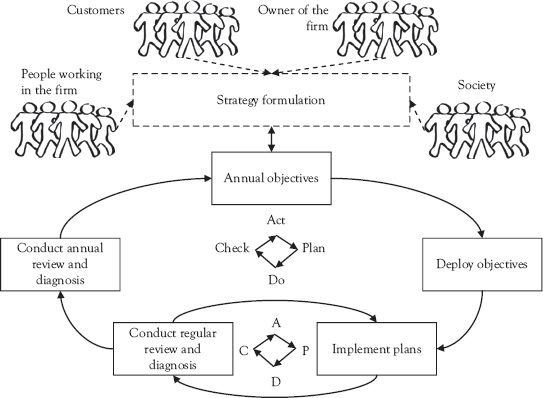

Figure 11.1 outlines the key phases and components of Hoshin Kanri. At the top is strategy formulation, which is the responsibility of senior management. By formulating a strategy, the top executives initiate a Hoshin Kanri cycle. Here the desires and needs of the different stakeholders are considered and integrated into a coherent strategy. These stakeholders are the owners of the firm, the customers, the people involved in the organization, and also society. All of us are stakeholders in a firm since we have to bear any environmental or societal consequences.

The Hoshin Kanri cycle itself is a repeating, periodic (typically on an annual basis), PDCA cycle that address Hoshin Kanri’s unique components.

- Plan: Hoshin Kanri starts with the Plan phase, which cascades senior management’s goals to the lowest organizational level as a set of annual hoshins. These annual hoshins communicate a company’s strategic goals and the proposed means to achieve these goals. The high level hoshins are initiated by senior management. They are refined as they cascade from one level of the organization to the lower level of the organization. Through this cascading process, goals are translated from competitive priorities into operational targets.

- Do: In the Do phase, the firm uses PDCA cycles to implement activities to realize the goals identified in the Plan phase.

- Check: The Check phase consists of a set of planned periodic reviews, which measure each unit’s progress versus its hoshin. The Check phase typically provides management the opportunity to identify any shortcomings in the plan and any unexpected influences that may undermine the hoshin. Where necessary, another PDCA cycle can be initiated to solve the problems.

- Act: The firm completes this Hoshin Kanri cycle in the Act phase by analyzing the data obtained during the Do and Check phases to determine what revisions to make to the hoshin (e.g., Babich 2005; Jackson 2006). Out of this a new Hoshin Kanri cycle is typically initiated. As mentioned earlier, this cycle through the phases is traditionally planned to take a year.

Figure 11.1 Hoshin Kanri

Plan Phase of Hoshin Kanri

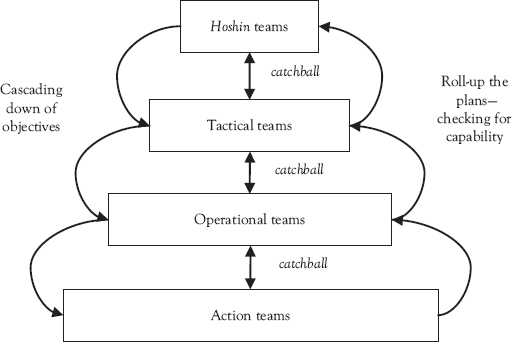

Hoshin Kanri’s planning process is a hierarchical process that links the different parts of the organization. For example, Jackson (2006) divides the organization into hoshin teams, tactical teams, operational teams, and action teams. Since each of these teams is supposed to work independently, a question of governance arises—how best to coordinate targets (and thus, activities) across these disparate teams?

The issuing of a hoshin by top management is one of the first coordination mechanisms used. Top management has to select, from the many important goals of a company (potentially hundreds), the set of goals that will be the firm’s focus during this hoshin cycle. Typically this is one to three goals or hoshins. The second important coordination tool in the hoshin is that it not only gives the goal, but it also gives the “means.” For example, a hoshin that states “Cost down 10 percent by improving quality” directs all units of the company to cut their costs, while improving quality. So, it would be inappropriate for a manager to reduce costs 10 percent by laying off all of their quality staff.

A second coordination mechanism at this stage is the catchball process (e.g., Jackson 2006). The term catchball refers to an iterative process in which information and ideas are “thrown” and “caught” vertically and horizontally throughout the organization. Catchball consists of discussion and feedback about goals and the means to achieve these goals (Cowley and Domb 1997). Structure and communication are important for a lean enterprise. While all companies perform some form of planning, it is the hoshin, issued from the top and adapted to the local environment as it cascades through the levels until it is operational, along with the catchball process that makes Hoshin Kanri unique.

As illustrated in Figure 11.2, the catchball process is used to first cascade down objectives by developing the plans. This is followed by a roll-up of the plans to consolidate local plans and check for the capability and likelihood of their execution (Bechtell 1996; Jackson 2006).

The catchball process includes formal and informal components. Nemawashi, which literally translates as “going around the roots,” is the informal part of the catchball process. Nemawashi is a preliminary step prior to a formal decision. As described by a Japanese senior executive:

… this is everybody understanding what is going on and agreeing that it is the right thing before you do it. If you want something done, you have to do nemawashi in the background so that when you come to do it you are straight in with no problem. (Witcher 2003, p. 92)

This type of informal consensus-building ensures continued buy-in as broad goals are translated into specific managerial actions.

Catchball should provide a psychologically safe environment. This means it should be appropriate to say that with the resources we have, the targets you want cannot be met. This process encourages employees to question top management’s plan in relation to their own work places.

Figure 11.2 Hoshin Kanri’s Plan phase—deploying goals and objectives

Do Phase of Hoshin Kanri

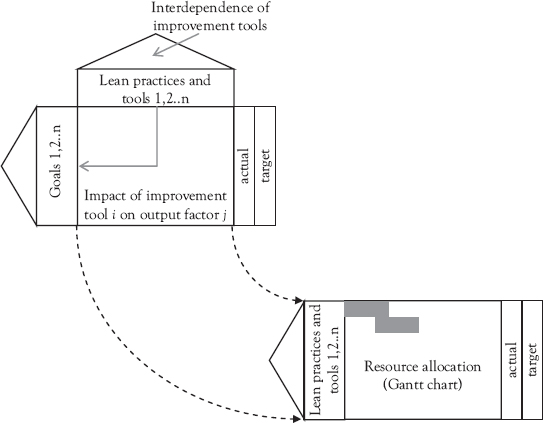

This phase of Hoshin Kanri identifies the specific means to achieve the goals determined during the planning phase and implements these means. It is here that most of the practices and tools of lean discussed in the second part of the book find their application. A simple tool to link lean practices and tools to goals is depicted in Figure 11.3.

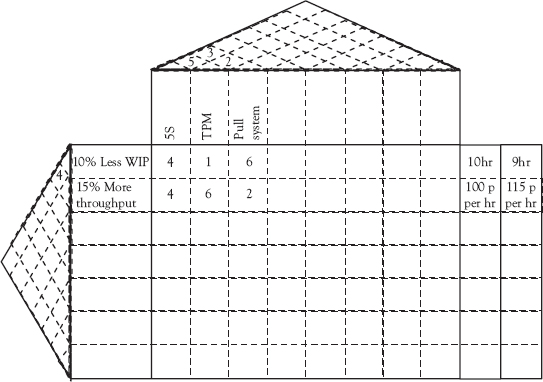

The house-like matrix is depicted individually in Figure 11.4. It links lean practices and tools to the different goals. In each cell the impact of a lean practice tool on a certain goal is evaluated, for example, rating it from 0 (no impact) to 7 (strong impact). In the roof of the house the correlation between goals and between lean practices and tools is also evaluated. The second matrix in Figure 11.3 (labeled “Resource Allocation”) determines the amount of resources or capacity allocated to each lean practice and tool. It also states when this resource or capacity is to be allocated.

Figure 11.3 Hoshin Kanri’s Do phase

Figure 11.4 Linking lean practices and tools to goals and objectives

For example, as shown in Figure 11.4 if the plan is to increase through-put by 15 percent in order to meet the higher hoshin goals, management might request resources such as trained facilitators in Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) to develop and implement a TPM plan in their unit. This might be planned for the first quarter of the year.

Check Phase of Hoshin Kanri

During this phase of Hoshin Kanri the progress of the plan is monitored. The plan is monitored at all levels. It is monitored most frequently at the lowest levels of the firm while at the top level it is monitored quarterly or semi-annually depending on the size of the firm. The lowest level might do an audit monthly. The next level would audit quarterly and so on. If problems are found in particular units with their progress toward accomplishing their hoshin, a PDCA cycle focused on correcting the deficiency can be initiated.

For example, the unit in Figure 11.4 had as part of their plan to increase throughput and that they would have implemented TPM by the end of the first quarter of the year. At the department level, the monthly audit would investigate whether the TPM training had been completed and whether there was a TPM plan in place for the critical machinery. The next monthly audit in this department might investigate the adherence of the operators to the TPM plan during the month. If it was discovered that two operators out of the 10 in the unit were not performing TPM correctly, additional training could be provided, or if it was determined that the problem was not training, but something else, then a PDCA cycle could be initiated to resolve the problem. At the end of the quarter, this department would again complete its monthly audit, but the unit to which the department belongs would also audit its overall performance for the quarter. The data gathered would be used to determine if the department was or was not on track to accomplish its annual hoshin. If the larger unit felt the department was not on track, a new PDCA cycle could be started to help identify any problems.

Act Phase of Hoshin Kanri

During this phase solutions are standardized. We have already discussed the importance of establishing standards in the previous chapter (Chapter 10). As we learned there, an important property of standards is that they should be constantly revised as necessary. The learning that occurred during the last year of the hoshin cycle is used to create standards, which are then used as the basis for the next hoshin. So a new hoshin cycle is initiated to further improve performance.

By evaluating how effectively the tools worked throughout the company, the company is practicing scientific management. It sets goals, and gathers data about how each unit in the company performs versus those goals. This data includes data about which tools were effective in various parts of the company. During the Act phase, the upper management is able to evaluate the capabilities of the various parts of the company, which provides them with information about which opportunities in the market place it is positioned to take advantage of in the future. It also becomes aware of where its lack of capabilities makes it vulnerable to competitors in the market place.

The Act phase provides an evaluation of the overall data and allows top management to intervene to adjust capabilities in its various units. In this way Hoshin Kanri is an answer to a problem in management that has long plagued many managers and management researchers.

Management’s primary job is to make organizations operate effectively. Society’s work gets done through organizations and management’s function is to get organizations to perform that work. Getting organizations to operate effectively is difficult, however. Understanding one individual’s behavior is challenging in and of itself; understanding a group that’s made up of different individuals and comprehending the many relationships among those individuals is even more complex. Imagine, then, the mind-boggling complexity of a large organization made up of thousands of individuals and hundreds of groups with myriad relationships among these individuals and groups. (Nadler and Tushman 1980)

References

Babich, P. 2005. Hoshin Handbook. Poway, CA: Total Quality Engineering, Inc.

Bechtell, M.L. 1996. “Navigating Organizational Waters with Hoshin Planning.” National Productivity Review 15, no. 2, pp. 23–42.

Cowley, M., and E. Domb. 1997. Beyond Strategic Vision: Effective Corporate Action with Hoshin Planning. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Dennis, P. 2007. Lean Production Simplified. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group.

Drucker, P. 1954. The Practice of Management. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Gittell, J.H. 2000. “Paradox of Coordination and Control.” California Management Review 42, no. 3, pp. 101–17.

Holt, A.W. 1988. “Diplans: A New Language for the Study and Implementation of Coordination.” ACM Transactions on Office Information Systems 6, no. 2, pp. 109–25.

Ishikawa, K.1990. Introduction to Quality Control. Portland, OR: Productivity Press.

Jackson, T.L. 2006. Hoshin Kanri for the Lean Enterprise: Developing Competitive Capabilities and Managing Profit. New York: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group.

Nadler, D., and M.L. Tushman. 1980. “A Model of Diagnosing Organizational Behaviour.” Organizational Dynamics 9, no. 2, pp. 35–51.

Ohno, T. 1988. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. 1st ed. New York: Productivity Press.

Witcher, B.J., and R. Butterworth. 1999. “Hoshin Kanri: How Xerox Manages.” Long Range Planning 32, no. 3, pp. 323–32.

Witcher, B.J. 2003. “Policy Management of Strategy (Hoshin Kanri).” Strategic Change 12, no. 2, pp. 83–94.