Digital technology allows companies to compete for talent in novel ways. Increased flexibility, in particular, opens new avenues for value creation (figure 11-1). For example, many employees are not assigned the number of hours they prefer to work. In a recent UK study, one-third of men and one-fourth of women indicated that they wanted to work fewer hours. About 6 percent hoped to work more hours.1 Digital technology can help avoid such mismatches. At the most extreme, digital platforms that pair workers and tasks provide complete flexibility. Maintenance workers on TaskRabbit, software engineers on Topcoder, data entry clerks on Mechanical Turk (MTurk), and scientists on InnoCentive are free to work whenever they please.

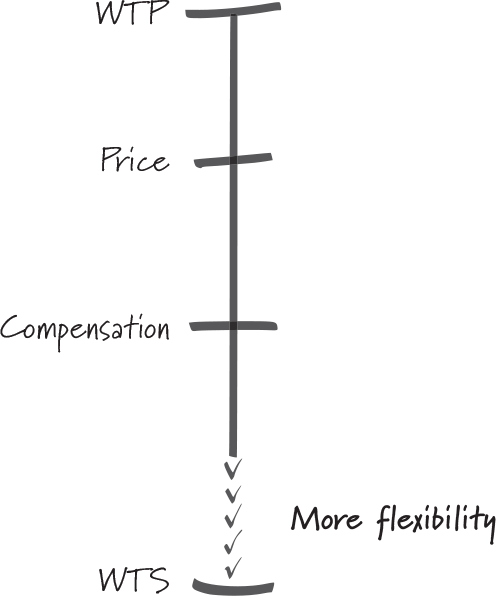

Figure 11-1 Gigs and passions

How much value is created when individuals are allowed to choose their hours?2 Uber is a good example. As is typical for gig work, drivers can drop in and out of the app with few limitations. Some pick only the most lucrative hours, when prices are particularly high. Others drive mainly when their principal job provides less income.*, 3 When Professor M. Keith Chen and his coauthors calculated willingness-to-sell (WTS) for 200,000 Uber drivers, they found huge differences across drivers and time.4 Figure 11-2 shows the WTS of 100 drivers in Philadelphia during the evening hours as an example.5

Figure 11-2 WTS for 100 Uber drivers in Philadelphia, evening drive time

The black dots represent the average WTS for each driver. The vertical lines show how much WTS varies for this person over time. Look at the first driver in figure 11-2. His average WTS is more than $70 per hour, but it ranges from less than $40 (his 10th percentile) to more than $100 (the 90th percentile). The horizontal lines in the figure show how much a driver would have earned if she drove during one of these evenings. Driver incomes hover around $20 per hour.* Given these values, our first driver will never work in the evening. His WTS is always greater than the hourly earnings. In fact, this person appears to have a very strong preference for not working in the evening; it takes more than $70 per hour to lure him on an average night. Perhaps he looks after his children, he may be concerned for his safety at night, or his spouse may use the family car in the evening. The drivers who do work are shown at the right in figure 11-2. On average, their WTS is $11.67.

The vertical lines give us a good sense of how much typical workers value the ability to choose work hours. With complete flexibility, drivers work only when their WTS is below the hourly earnings. Compare this to a job with no flexibility—say, the fixed shift of a regular taxi driver. This driver would sometimes have to work when his WTS is greater than compensation—value is being destroyed—and he would sometimes be unable to drive when his WTS is below hourly earnings, a missed opportunity to create value. The difference between Uber and an inflexible taxi arrangement, Professor Chen and his colleagues calculate, is $135 per week.6 In other words, flexibility creates as much value as driving 6.7 hours!

Flextime on Demand

Digital platforms like Uber are not alone in recognizing the advantages of flexible work hours. Flextime programs have arrived in many businesses. We have already seen how Gap’s Shift Messenger allowed staff to trade hours. Other flextime policies include time-shifting, micro-agility (the ability to freely move some hours—for example, to attend a child’s school play), part-time work, compressed hours (employees work full-time but over fewer days), periods of minimal travel, job sharing, and longer-term opportunities such as paid leave, sabbaticals, and even ways to “dial up” or “dial down” one’s career, as in Deloitte’s mass career customization program.7 In a recent survey of 750 companies around the world, 60 percent said they allowed some of their employees to choose when to start and end their workdays. One-third offered compressed hours.8 It seems likely that the global pandemic will accelerate this shift toward flexible work arrangements.

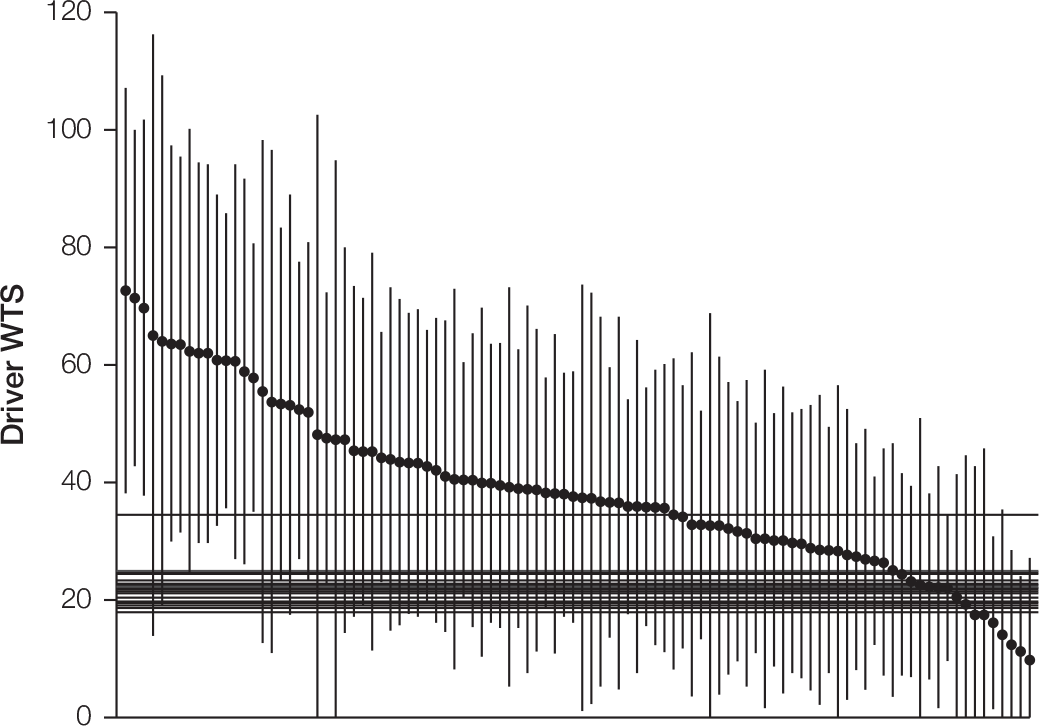

While companies have made significant progress, the demand for flexibility still outstrips current policies in many firms. When Annie Dean and Anna Auerbach, co-CEOs of Werk, a human resource startup, asked 1,500 white-collar professionals about workplace flexibility, the answers revealed a large gap between company programs and the preferences of these professionals (figure 11-3).9

Figure 11-3 Workplace flexibility gaps, survey of white-collar professionals

An even bigger challenge is the acceptance of flextime programs. Introducing them is a first step; getting employees to actually use them is another. Professional services firms are a case in point: nearly all of them have flextime policies, but most employees do not take advantage of them.10 A prime reason is that consultants and bankers believe they hurt their career chances when they ask for flextime. In the words of one line manager, “The culture here is to dedicate your life and soul to the bank. That’s how people at the top got there…. If you ask for time off or flexible hours, you’re considered a wimp.”11 Women’s career prospects especially are harmed when they take advantage of flextime policies.12

As you think about ways to create value for the employees in your organization by way of flexible work arrangements, keep the following in mind.

- Employees are more likely to make use of flextime when KPIs emphasize productivity, not long hours. In a billable-hours culture, for instance, flextime programs are unlikely to make a difference.

- Role models matter. Where (some) senior managers work flexibly, flextime is seen more positively throughout the organization.13

- Make flextime a point of open conversation. Research shows that most individuals believe others view flextime workers less positively than they themselves do. Honest conversations can help reduce this collective bias.14

- Refrain from celebrating a long-hours culture. Kate Hamp, HR business partner at the price comparison site Moneysupermarket.com, explains: “If someone completes a big project or wins an internal award, we ask managers not to applaud long hours.” Moneysupermarket.com built an effective flex culture that emphasizes decentralized decision-making—individuals and teams determine the specific parameters of their flextime policy—and informal arrangements, a chat with the boss as opposed to a clause in one’s contract.15

Enter Passions

Flexibility is of substantial value in many contexts. But it can be truly transformational when coupled with personal passions. Think about your own interests. What is your favorite pastime? Are you a gardener? Writer? Movie buff—excuse me—cinephile? Our passions move WTS in a powerful way. We all have activities that we pursue for pure enjoyment, no compensation needed. WTS is zero (or even negative if you are willing to pay good money to engage in your favorite hobby). While passions lower WTS, the time we spend on our favorite activities is a countervailing force. Imagine gardening during all waking hours. Unless you are wealthy, you would have to find a way to turn your hobby into a job. The more time you spend on your passions, the more expensive it is to pursue them because you are missing out on other opportunities, in particular the chance to earn an income. WTS will reflect this opportunity cost of time. For this reason, it is particularly compelling to combine limited-time work engagements and personal passions.

Historically, it has been difficult to connect people’s passions to business activity. There were two principal challenges. First, it was not easy to find people with a particular passion. More importantly, even a passionate person’s opportunity cost of time (and hence their WTS) will be substantial if we ask her to commit to many hours of work. The advent of the internet has substantially reduced both of these obstacles. It is now far easier to meet people with particular passions, and the passionate can pursue their pastimes at low levels of intensity, keeping opportunity cost in check and WTS low.

Travel writers, citizen journalists, graphic designers, book critics, freelance photographers: across many professions, passionate individuals pursue the activities they enjoy most. Food52, an online community for people who love cooking, operates a kitchen hotline that answers burning questions in real time. The hotline is “staffed” by 50,000 professional chefs and kitchen enthusiasts who freely share their expertise (and recipes) with the 1 million members of the Food52 community.16

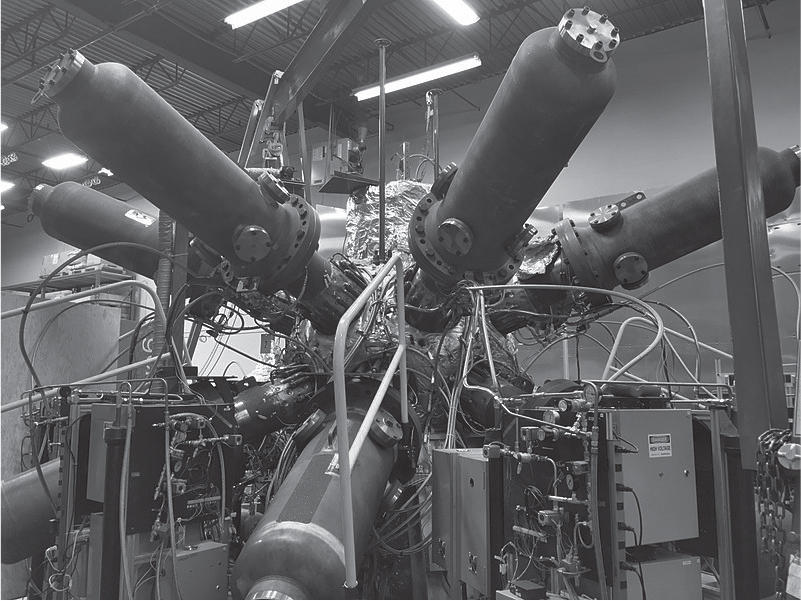

Another example is General Fusion, a Canadian company that aspires to develop commercially competitive fusion power. The company’s approach is to smash 220-pound hammers against a sphere to produce a pressure wave through liquid lead. Figure 11-4 shows the pistons that house the hammers.17 Brendan Cassidy, who manages open innovation at the company, explains how General Fusion tapped into the passions and expertise of scientists and engineers: “The issue we had was that the anvil on the surface, which is what the hammer hits, needs to seal inside the vessel molten metal and create a vacuum on the outside of the anvil.… This was a case where we said, ‘You know, this is not our expertise. We’ve learned a lot about building these hammers, but as far as the best way to create a seal, there’s probably people who have experience.’”18 To benefit from the experience of others, General Fusion turned to InnoCentive, an online platform that connects companies to a network of nearly 400,000 experts. Some 229 engineers accessed General Fusion’s technical brief, 64 submitted solutions, and the company awarded Kirby Meachum, an MIT-trained engineer, $20,000 for his proposal.

Figure 11-4 General Fusion array of pistons designed to compress plasma

From simple cooking recipes to highly technical advice, an increasing number of companies now routinely rely on outside creatives and experts to build their business and accelerate innovation. It is no coincidence, of course, that a list of the services these professionals provide includes mostly activities that are intrinsically interesting and intellectually stimulating. The economics of community-based businesses (Food52) and open innovation (InnoCentive) are advantageous because they combine passion with short stints of work. (The “gig” in “gig economy” is jazz-musician slang from the 1920s, meaning a short-term engagement.) Put passion and short assignments together, and you are likely to see superb quality and reasonable remuneration. Food52 awards its “contributor of the month” $25. InnoCentive has helped address complex technical challenges for organizations as diverse as BP, NASA, and Prize4Life, a nonprofit that hopes to find a biomarker for Lou Gehrig’s disease. Across all its contests, the expected value of participating in an InnoCentive challenge is $125.19

Crowdspring, an online marketplace for graphic design services, is a good example of the reach of platforms that connect businesses to outside talent. One of Crowdspring’s specialties is logo design contests. In these competitions, brand managers describe their desired logo, and designers from a network of more than 200,000 freelancers submit proposals. A typical contest attracts about 35 designers who produce 115 designs.20 Companies then provide feedback so that the designers can improve their work. Projects run for seven days. The company pays the winning designer a prize, generally about $300. In exchange, the brand owns the copyright.

My colleague Professor Daniel Gross studied more than 4,000 of these design contests to better understand how feedback improves quality (it has a large positive effect) and whether seeing the feedback that others receive influences continued participation (the weakest designers do give up early). In a clever research design, Professor Gross also calculated the benefits and costs of participating in Crowdspring’s design competitions. The result of these calculations is shown in figure 11-5.21

Figure 11-5 Logo design contests

Collectively, the designers incur far greater costs than the prizes justify. If all designers had a good sense of their probability of winning, aggregate costs and prizes would balance, and in figure 11-5, we would never see contests with cost-prize multiples that exceed 1. In practice, however, it appears that too many designers work for too little money.

Is the promise of gig-economy platforms to deliver high quality at low prices an illusion? Is the truth that the benefits of gig work come at the expense of (mostly desperate) freelancers? As a businessperson who wants to do the right thing, should you ever say no when someone is willing to provide high-quality work for little money? These questions are at the very heart of the debate about gig-economy platforms and the need to regulate these businesses.

Let’s explore these issues using the principle of value creation as our moral compass. Business practices are defensible as long as they make employees and independent contractors better off. Freelancers working for little money is not per se an indication that they are being exploited; their WTS for the task might be really low. But it is a warning sign that warrants further investigation. My hope is that you will ask questions such as these.

- Is it even plausible that WTS is low? For work that is not intrinsically attractive, the answer is probably no. Remember, it is passions that drive down WTS. Also, contractors for whom the work constitutes their principal income are unlikely to have low WTS. For example, a work arrangement with a person whose full-time job is to clean homes should not be based on a premise of low WTS.

- Does the work arrangement create value other than financial compensation? One reason that some of Crowdspring’s designers work for small prizes is that they expect benefits other than money. Some hope to learn from company feedback. Others seek to build a reputation. In some cases, companies will ask for (better-compensated) follow-on work. General Fusion, for instance, ended up contracting with Kirby Meachum to further develop his ideas. Logo designers at times continue to design the company’s websites.

- Are expectations of longer-term benefits reasonable? It is not easy for gig workers to estimate the value of longer-term benefits. What is the likelihood that a poorly paid freelancer will be awarded additional work? How likely is it that an unpaid engagement will open the door to a permanent position? Often, the business is better informed about the longer-term prospects than the freelancer. It is imperative not to exploit this information advantage. For instance, two-thirds of Uber drivers who start driving for the company abandon the platform after six months.22 One interpretation is that drivers work for Uber only when they are in a bind. Another is that Uber does a poor job of setting the expectations of its drivers.

- Is it in the best interest of your business to respond to low WTS with low compensation? HuffPost, a US news and opinion website, was one of the first to rely on citizen journalists and aspiring writers. By 2018, more than 100,000 contributors had provided HuffPost with content—for free! But early that year, it all came to an end. HuffPost closed its contributor platform and shifted its focus to a smaller set of paid journalists who would produce “smart, authentic, timely and rigorous op-eds.”23 Other publishers with large contributor communities, such as Forbes and Hearst, followed suit.24 Paying nothing for content, it turned out, produced a tsunami of stories of highly variable quality. “Media companies have flown into higher-quality content,” explains Pau Sabria, cofounder of Olapic, a startup focused on employing user content in marketing. “You cannot afford to [provide readers with] a bad experience when you’re competing with other forms of media.”25 You are, of course, familiar with this effect from the beginning of this chapter. Compensation policies induce powerful selection effects. Even in cases with genuinely low WTS, sharing more value with employees and freelancers can have a profound impact on the quality of work.

Looking at flexible work arrangements and gig-economy business models, I take away a number of insights.

- Digital platforms that connect companies with passionate workers can help shift corporate boundaries. Activities that used to sit inside the firm can now be moved outside or combined in novel ways with efforts by gig workers and independent contractors. More often than not, the results show superb quality at a favorable cost. In the United States, about 10 percent of the workforce is now engaged in alternative work arrangements.26 If you do not think about ways to shift corporate boundaries to attain a cost advantage, your competitors are.

- Even in 2020, workplace flexibility is still in short supply and is an effective tool to lower WTS.

- Developing rules for flexwork is only a first step. Encouraging employees to make use of the flexibility often requires a broader change in culture. As a leader in your organization, your behavior will influence many others, irrespective of whether you intend to serve as a role model.

- Linking people’s passions to your business purpose is an exciting avenue for value creation. This works best if the projects and activities are intrinsically interesting and require a limited time commitment.

- Engaging passionate individuals requires careful consideration of their expectations. Gig work can create substantial value for workers but it also risks exploiting them. The best companies develop firm guidelines and practices that ensure gig workers have reasonable expectations and get to share in the value that is being created.