Chapter 7

The Foreign Exchange Market

Foreign Exchange Market Snapshot

History: Since time immemorial, foreign exchange trading was conducted almost solely for the purpose of enabling international trade in goods and services. However, with the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in 1971, the foreign exchange (forex, FX) market has experienced exponential growth powered by improved technology, the unrelenting dismantling of foreign exchange controls, the accelerating pace of economic globalization, and the design of powerful algorithmic trading models. It is now an asset class in its own right.

Size: The over-the-counter foreign exchange derivatives market has grown from $18 trillion in 1998 to $49 trillion in 2009. The exchange-traded market, which is exceptionally smaller than the OTC market, has increased from $81 billion in 1998 to $311 billion in 2009.

Products: Major foreign exchange products include spot and forward contracts, as well as currency swaps, options, and swaptions. Exchange-traded currency futures and options are also widely-used instruments.

First Usage: The first widely-publicized OTC foreign exchange derivative was a currency swap that was executed in 1979, when IBM and the World Bank agreed to exchange interest payments on debt denominated in different currencies—the Swiss franc and German mark from IBM were exchanged for U.S. dollars from the World Bank.

Selection of Major Forex Derivative Debacles

1987: Volkswagen AG, the German car manufacturer, had a policy of keeping itself fully hedged against foreign exchange risk. However, managers who were responsible for forex risk management failed to put on the appropriate currency hedges. When exchange rates moved against the firm, employees hid their failure to put on and maintain appropriate hedges by falsifying documents to indicate that they did have the necessary hedging contracts in place. Later, when senior management sought to enforce these contracts they discovered that the contracts did not exist. The forgery of the contracts was discovered by the National Bank of Hungary and eventually led Volkswagen to recognize losses of $259 million.

1991: Allied-Lyons—better known for its tea bags than for its forays into the currency market—announced a stunning $269 million forex loss (approximately 20 percent of its projected profits for 1991). Facing a sluggish economy, its treasury had elaborated a sophisticated scheme that gambled not so much on the absolute level of the dollar/sterling rate as on its volatility. This gamble was achieved by writing deep-in-the-money currency options in combinations, known as straddles and strangles, that in this particular case would have produced profits had the exchange rate turned out to be less volatile than the option premium implied. This ingenious scheme was implemented at the beginning of the Gulf War. However, when the allies launched their air offensive, the initial uncertainty as to the outcome did not reduce the option volatility—at least not soon enough for Allied-Lyons to see its speculative gambit succeed and it was forced by its bankers to liquidate its options position at a considerable loss.

1993: Showa Shell Sekiyu KK, a large oil refinery in Japan, expected the U.S. dollar to rise against the Japanese yen, and thus started to buy currency forwards in 1989 to hedge its dollar-denominated oil bill. However, the dollar fell against the yen, thus engendering enormous exchange rate losses for the company. The situation deteriorated when the treasury department of the firm tried to conceal the losses by rolling over its positions (with the tacit cooperation of its counter-party banks), eventually accumulating losses of $1.5 billion.

2002: Allfirst Bank, a former subsidiary of Allied Irish Banks, Ireland's second-largest bank, hired a trader in 1993 named John Rusnak, who took long positions in Japanese yen by purchasing currency forward contracts. However, as the yen continued to appreciate, Rusnak faced losses on his unhedged positions. In order to cover up his losses, Rusnak wrote pairs of bogus put and call options, which were deceitfully entered into the Bank's systems to give the impression that his positions had been hedged. Rusnak opened up a prime brokerage account and continued betting on a rise in the yen until his scheme was discovered by the parent bank. His total losses amounted to $691 million.

Best Providers (as of 2009): Deutsche Bank was nominated by Global Finance magazine as the Best FX Derivatives Provider in North America, Europe, and Asia.

Applications: Participants in the forex markets use foreign exchange contracts and derivatives to execute cross-border commercial transactions, to hedge currency exposures, to engage in various forms of arbitrage and carry trades, and to speculate on currency exchange movements.

Users: The forex customer market refers to the market for end users of foreign exchange. Customers would include importers and exporters, multinational corporations, central banks intervening in the forex market or simply managing their currency reserves, commercial banks, insurance companies, investment banks’ proprietary trading, and hedge funds involved in carry trades or other forms of high-frequency algorithmic trading.

INTRODUCTION

If there were a single world currency there would be no need for a foreign exchange market. At its simplest, the raison d’être of the foreign exchange market is to enable the transfer of purchasing power from one currency into another arising from the international exchange of goods, services, and financial securities. Trade carried over great distances is probably as old as mankind and has long been a source of economic power for the nations that embraced it. Indeed, international trade seems to have been at the vanguard of human progress and civilization: Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans were all great traders whose activities were facilitated by marketplaces and money changers that set fixed places and fixed times for exchanging goods. Indeed, from time immemorial, traders have been faced with several problems: how to pay for and finance the physical transportation of merchandise from point A to point B (perhaps several hundred or thousands of miles away and weeks or months away), how to insure the cargo (risk of being lost at sea or to pirates), and last, how to protect against price fluctuations in the value of the cargo across space (from point A to point B) and over time (between shipping and delivery time). In many ways the history of foreign exchange and its derivative contracts parallels the increasingly innovative remedies that traders devised in coping with their predicament.

Long confined to enabling international trade, foreign direct investment, and their financing, foreign exchange has recently emerged as an asset class in its own right. This largely explains the recent surge of money flowing through the foreign exchange (forex) market. Catalyzed by improved technology, the unrelenting dismantling of foreign exchange controls, the accelerating pace of economic globalization, and the design of powerful algorithmic trading models, the daily turnover in the forex market now exceeds $3 trillion, thus dwarfing equities and fixed-income securities markets. Surprisingly, though, the international trade of goods and services accounts for only 5 percent of trading.

This chapter first describes the institutional framework within which forex transactions are carried out, emphasizing how Internet-based electronic automation has overhauled the market microstructure. Second, it maps the rules of the game that determine the price—foreign exchange rate—at which such transactions are completed. Third and last, it shows how the 1971 breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, that had long provided free-of-charge risk-avoidance services to market participants, spurred the engineering of risk management products—namely, futures, options, and swaps: In effect, central banks had privatized risk management.

HOW FOREX IS TRADED: THE INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK

The forex market is by far the oldest and largest market in the world. Unlike the New York Stock Exchange, the Paris Bourse, or the Chicago Board of Trade, which are physically organized and centralized exchanges for trading stocks, bonds, commodities, and their derivatives, the foreign exchange market is made up of a network of trading rooms found mostly in commercial banks, foreign exchange dealers, and brokerage firms—hence its description as an interbank market. It is largely dominated by approximately 20 major banks, which trade via their branches physically dispersed throughout the major financial centers of the world—London, New York, Tokyo, Singapore, Zurich, Hong Kong, Paris, and so on.

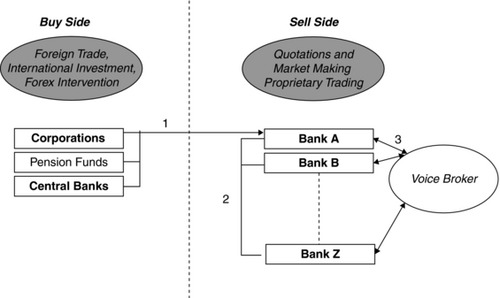

In the 1960s, foreign exchange trading rooms were linked by telephones (and later telexes), which allowed for very fast communication (but not quasi-instantaneous as today, with computer terminals and the Internet) in this over-the-counter market. Each currency trader would have “before him a special telephone that links the trading room by direct wire to the foreign exchange brokers, the cable companies, the most important commercial customers. … The connections are so arranged that several of the bank's traders can ‘listen in’ on the same call.” (Holmes and Scott, 1965) See Exhibit 7.1.

Exhibit 7.1 The Phone-Forex Market (until the Early 1990s)

Today foreign exchange trading rooms are linked electronically, with traditional means of telecommunications such as telephone, telex, and facsimile machine playing a subsidiary role: Computer terminals have established themselves as the undisputed medium of transaction, as they allow for instantaneous communication in this over-the-counter market. Foreign exchange traders with display monitors on their desks are able to execute trades at prices they see on their screens by simply punching their orders on a keyboard.

Indeed, the new computerized system offers currency traders the opportunity to enter orders that are then automatically matched with other outstanding orders already in the system. This globally reaching and linking trading system substantially cuts the time and cost of matching and settling trades and, more importantly, provides the foreign exchange market with the ticker tape to record the actual prices at which foreign exchange transactions are carried out. It should be emphasized that this information has, so far, never been made public, since foreign exchange markets’ biggest traders have profitably kept this secret to themselves.

This ethereal, ubiquitous, electronic foreign exchange market is trading literally around the clock. At any time during a 24-hour cycle, forex traders are buying and selling, say, pounds for yen somewhere in the world. By the time the New York foreign exchange market starts trading at 8:00 A.M. ET, major European financial centers have been in full swing for four or five hours. San Francisco and Los Angeles extend U.S. forex trading activities by three hours, and by dinnertime on the West Coast, Far Eastern markets, principally Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Singapore, will begin trading. As these market trading activities draw to a close, Bombay and Bahrain will have been open for a couple of hours, and Western European markets will be about to start trading.

One major implication of a 24-hour currency market is that exchange rates may change at any time in response to any new information. Thus, foreign exchange traders must be light sleepers ready to work the night shift if necessary since they may need to act on news resulting in a very sharp exchange rate movement that occurs on another continent in the middle of the night.

Products

There are four major types of products traded in the forex market: spot contracts, forward contracts, forex swaps, and currency swaps. In all cases contracts are tailor-made1 —that is, negotiated by the two counterparties in amounts of no less than $1 million.

1. Spot contracts are transactions for the purchase or sale of currency for currency at today's price for settlement within two business days (one day if both parties are domiciled in the same time zone, such as U.S. dollar for Canadian dollar or Mexican peso).

2. Forward contracts are agreements in terms of delivery date, price, and amount set today to purchase or sell currency for currency. Delivery date at some time in the future (anytime between one week and 12 months for the most part), at a price agreed upon today, and known as the forward rate. If the forward contract is not matched with a spot transaction it is known as an outright forward.

3. Forex swaps. If combined with a spot transaction, a forward contract is referred to as a swap. More specifically, foreign exchange swaps combine two transactions of equal amount, mismatched maturity, and opposite direction; for example, the bundling of the spot purchase of €10 million for U.S. dollars at today's price of $1.50 = €1 with the 60-day forward sale of the same amount of €10 million at the forward rate2 of $1.48 = €1 would constitute a foreign exchange swap.

4. Currency swaps and cross-currency swaps, which should not be confused with FOREX swaps above, are similar in structure to interest rate swaps. One leg typically pays interest on a given quantity of notional principal in one currency, and the other leg pays interest on a given quantity of notional principal in a different currency. As a practical matter, it is often only the difference between the two payments that is actually paid by the higher paying counterparty to the lower-paying counterparty. These sorts of swap contracts do not necessarily require the actual exchange of currencies either at the beginning or the end of the contract's life.

According to the most recent triennial survey by the Bank for International Settlements’ Triennal survey (2010), the forex market averaged $3.2 trillion of trading per day in April 2007, with one-third accounted for by spot transactions (for comparison, Wall Street has a daily turnover of approximately $75 billion). The U.S. dollar was involved in 86 percent of all forex transactions, with the euro a distant second at 37 percent. London is the undisputed hub of forex trading with an average daily volume of $1,359 billion, followed by New York City with $661 billion during the same month of April 2007. The forex market is made up of two distinct but closely connected tiers: the customer market (buy side) and the interbank market (sell side).

Buy Side Meets Sell Side in the Forex Market3

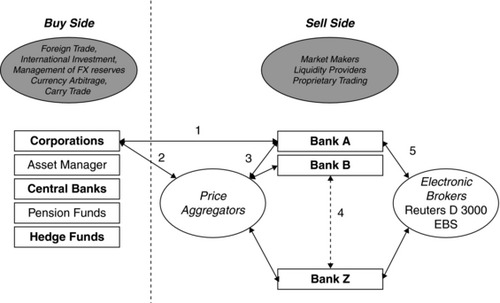

The customer market refers to the market for end users of foreign exchange. Customers include importers and exporters; multinational corporations repatriating dividends, extending an intra-corporate loan to one of their foreign affiliates, or concluding a cross-border acquisition; central banks intervening in the forex market or simply managing their currency reserves; commercial banks; insurance companies; investment banks’ proprietary trading; and hedge funds involved in carry trades or other forms of high-frequency algorithmic trading (see left panel of Exhibit 7.2).

Exhibit 7.2 The e-Forex Market (from the Early 1990s to the Present)

Because it would be difficult for customers to find another customer counterparty directly, they would turn to their bank and declare their intention to trade. In fact, some of the largest market makers in forex trading, such as Deutsche Bank, Barclays, and UBS, have developed their own electronic trading platforms that facilitate bank-customer relationships.

Increasingly the buy side would rather access a multiple-dealer portal that functions as a price aggregator or bulletin board streaming quotes from key dealer banks and routing buy-side orders to the most cost-effective sell-side providers (Exhibit 7.2, arrow 2). Today this consumer segment would rather have direct access to an electronic communication network (ECN) such as FXall, FXconnect, or Currenex. ECNs are electronic trading systems that automatically match buy and sell orders placed by various customers. Access to ECNs is limited to subscribers, who must also have an account with a broker-dealer before their orders can be routed for execution. ECNs post orders on their systems for other subscribers to view and then automatically match orders for execution.4

The Interbank Market

The bank in turn will give quotes either directly to its customers, thereby acting as a market maker5 (Exhibit 7.2, arrow 1), or via multiple-dealer portals. The bank would hope to use its existing inventory of foreign exchange to meet its customers’ needs but is often unable to do so. The bank's dealer/trader will then turn to the interbank market to cover his customers’ trades. The dealer/trader will quote buying and selling rates to another bank (bilateral trade) without revealing his real intentions (but revealing his identity) as to whether he is interested in buying or selling or how much of the currency he is interested in trading (Exhibit 7.2, arrows 2 and 3). The advantage of direct trading is that no commission would have to be paid, but there is no guarantee that the trader has secured the best bargain. Indeed, there are more than 1,000 banks trading foreign exchange and probably more than 10,000 forex traders. Direct trading is thus decentralized and fragmented since transactions amount to bilateral deals between two dealers and cannot be observed by other market participants. However, it should be noted that approximately 10 banks account for a disproportionate 50 percent share of forex trading in each currency pair. Specialization, in terms of currency pairs traded, is widely known among market participants, which facilitates bilateral direct trading. However, it is next to impossible to know, in such a physically dispersed market, if the best possible deal has been secured.

Electronic Brokers

Hence the second approach is for the bank forex trader to contact a broker (formerly referred to as a “voice broker,” but more likely to be known today as an electronic broker); this is known as indirect trading6 (Exhibit 7.1, arrow 4). Brokers are sometimes referred to as bulletin boards. “Brokers do not make prices themselves. They gather firm prices from dealers, and then communicate those prices back to dealers.” (Lyons 2001, p. 40.) Such broker-intermediated trading used to be conducted over the phone, but today forex brokering is channeled through two dominant computer systems—Reuters D30007 and Electronic Broking Services (EBS).8

EBS dominates trading in the three major currency pairs—dollar/euro ($/€), dollar/yen ($/¥), and euro/yen (€/¥)—whereas Reuters leads in pound (£) trading and other lesser or emerging market currencies. Both electronic platforms are in effect electronic limit order books akin to the electronic trading systems used by stock exchanges. A limit order book aggregates buy and sell orders for a given currency by order of priority. Dealers when entering their order will also specify the volume they intend to buy/bid or sell/ask as well as the price at which to buy or sell. The order is kept in the system until a corresponding order with matching volume and price is entered or the order is revoked/withdrawn by the original bidder. Posting limit orders through brokers will also protect the dealer's identity. Brokers serve as matchmakers and do not put their own money at risk. Through computerized quotation systems, such as Reuters D3000 or EBS, electronic brokers monitor the quotes offered by the forex trading desks of major international banks. By continuously scanning the universe of forex traders, brokers perform a very useful searching function and provide the bank's forex trader with the best possible price. Such service is provided at a cost to its user, as dealers will pay commissions to brokers with the hope of having accessed the best possible deal.

Has the human trader at major dealer banks been completely disintermediated as a result of electronic automation of forex trading? Not quite. According to several industry reports, approximately a third of all forex transactions continue to be intermediated by traditional traders. The buy side of the market is consciously channeling a significant proportion of its business to forex dealers to keep the relationships alive, as it values the advisory content of human contact with traders. This is particularly true in times of market turbulence and high price volatility, when forex traders prove to be especially useful as algorithm pricing tends to err, if not outright fail. Similarly, currencies that are more lightly traded, and the more idiosyncratic, tailor-made forex products, will benefit from the human touch.

Further strengthening the functioning of the interbank market is the newly established settlement service CLS Bank (Continuous Linked Settlements), which began operating on September 9, 2002, and links all participating countries’ payment systems for real-time settlement. This eliminates or greatly reduces counterparty or default risk in the settlement of spot transactions.9

Algorithmic Forex Trading

Since foreign exchange is widely considered an asset class, hedge funds and other institutional investors are increasingly relying on automated trading models that seek and act instantly on market opportunities to generate alpha. As new forex quotes and news items arrive on the news feed, they are instantly incorporated in pricing and trading algorithms, which will trigger a buy or sell order on a particular currency. Banks, in turn, have built pricing algorithms to handle this new high-speed flow of forex trading, and corporations have followed suit by engineering their own hedging algorithms.

Market Efficiency

As emphasized earlier, the forex market is best described “as a multiple-dealer market. There is no physical location—or exchange—where dealers meet with customers, nor is there a screen that consolidates all dealer quotes in the market” (Lyons 2001, p. 39). Because of its idiosyncratic microstructure, the order flow of foreign exchange transactions is not nearly as transparent as it would be in other multiple-dealer markets. There are no disclosure requirements for forex trading as one would find in most bond and equity markets, where trades are disclosed within minutes by law. Because trades or order flow are generally not immediately observable, the critical information about fundamentals that would have otherwise been made available to all market participants is released more slowly, thus impairing the efficiency of the forex market.

However, electronic trading is metamorphosing the price discovery process and speeding up price dissemination to the point of becoming quasi-instantaneous. Indeed, with dealers and most customers now able to access current prices in real time, the over-the-counter forex market is gaining increasing transparency. With price discovery becoming quasi-automated and increasingly centralized, this over-the-counter market is taking on some of the characteristics of centralized exchanges. However, if increased transparency and speedy, widespread price dissemination are bolstering the informational efficiency of the forex market, it remains that intervention in the spot market by secretive central banks continues to be a major impediment.

HOW ARE EXCHANGE RATES DETERMINED?

The breakdown of the international monetary system of fixed exchange rates that had prevailed until 1971 under the Bretton Woods agreement, ushered the world economy into uncharted territories. The new international financial order that has emerged in its stead is commonly characterized as a system of floating exchange rates. Such a characterization, however, is misleading since it applies to only a handful of major currencies that float independently, such as the U.S. dollar ($), the Japanese yen (¥), and the euro (€). Most other currencies are actually closely managed by their respective central banks when they are not actually pegged to or tightly stabilized vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar, the euro, or a basket of currencies. This section develops a framework for understanding how exchange rates are determined and how different exchange rate regimes have evolved in each country: it provides a theoretical backdrop against which the operational framework for forex trading presented in the first part of this chapter should be understood.

First Principles about Exchange Rate Determination

International transactions have one common element that makes them different from domestic transactions—namely, one of the parties involved must deal in a foreign currency. When an American consumer—admittedly well-heeled—imports a British-made Aston Martin, the car buyer pays in either dollars or British pounds. If the buyer pays in dollars, the British manufacturer must convert the dollars into pounds. If Aston Martin receives payment in pounds, the American buyer must first exchange his or her dollars for pounds. Thus, at some stage in the chain of transactions between the American buyer and the British seller, dollars must be converted into pounds. The medium through which this can be achieved is the foreign exchange market. The basic function of such a market is thus to transfer purchasing power from the U.S. dollar into the British pound.

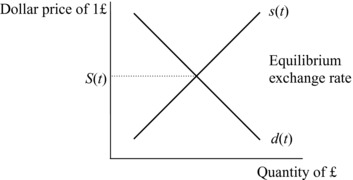

Examples analogous to the preceding case of an import transaction could be multiplied. Generally, the demand for pounds arises primarily in the course of importing British goods and services such as shipping or insurance, as well as making investments in sterling-denominated stocks and bonds or extending loans to the United Kingdom. Conversely, the supply of pounds results from exporting/selling U.S. goods, services, and securities to the United Kingdom, as well as receiving investments and loans from British institutions. The interaction between supply s(t) of and demand d(t) for pounds thus sets the price at which dollars are going to be exchanged for pounds for immediate delivery (within one or two business days); it is defined as the spot exchange rate S(t).

The free interplay of demand for and supply of pounds thus determines the equilibrium rate of exchange. At this rate of exchange and at no other rate, the market is cleared, as illustrated in Exhibit 7.3. The pound, like any other commodity, has thus a price at which it can be bought or sold. As an illustration, assume that on December 1, 2009, the dollar price of one pound is US$1.71 for spot or immediate delivery (that is, within one or two business days). Clearly, the United States deals with a multitude of countries besides the United Kingdom, and for each conceivable pair of countries (United States, country i), there will exist a foreign exchange market allowing the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar to be transferred into currency i and vice versa.

Exhibit 7.3 Equilibrium Exchange Rate

The concept of a foreign exchange market, as presented in the previous section, comes as close to the perfectly competitive model of economic theory as any market can. The product is clearly homogeneous, in that foreign currency purchased from one seller is the same as that foreign currency purchased from another. Furthermore, the market participants have nearly perfect knowledge, since it is easy to obtain exchange rate quotations from e-forex price aggregators in real time. And there are indeed a large number of buyers and sellers.

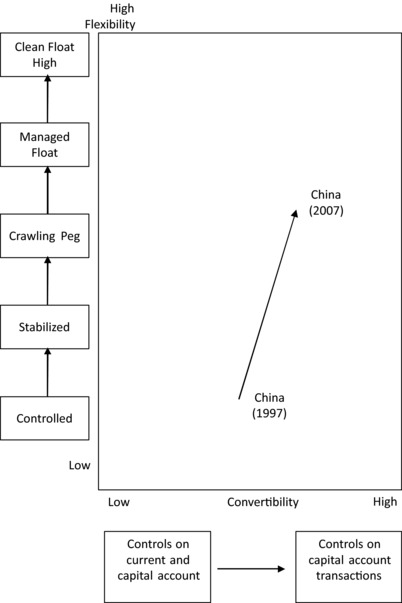

Yet the actual exchange market deviates from the model of a perfect market for two reasons: (1) the foreign exchange market is physically and geographically dispersed with no direct way for market participants to monitor the order flow of transactions,10 and (2) central banks act as a major agent of price distortion, either by directly intervening in the foreign exchange market, and thereby impairing the flexibility of exchange rates or, indirectly, by limiting entry to the market (exchange controls), and thereby limiting the convertibility of the currency. In other words, the first source of price distortion is simply limited flexibility, whereas the second is limited convertibility. In this vein it is helpful to think of a country's exchange rate regime along the two dimensions of (1) flexibility ranging from 0 percent (controlled rate) to 100 percent (clean float) and (2) convertibility ranging from 0 percent (tight controls on all current and capital account transactions) to 100 percent (absence of controls on all balance-of-payments transactions). On the chart in Exhibit 7.4 we portray the story of China, which over the past 10 years has moved cautiously toward higher convertibility and since 2005 toward timid flexibility. The case of China is actually representative of many emerging market countries that are steadily moving toward more flexibility and more convertibility: Adam Smith's invisible hand is reasserting itself in Exhibit 7.4.

Exhibit 7.4 The Currency Flexibility x Convertibility Space

Indeed, central banks are unlike any other participant in the forex market: they pursue objectives of national interest guided by their fiscal and monetary policies—they are not profit-maximizing entities. Why, how, and to what extent central banks actually do limit fluctuations in market prices are major factors constraining exchange rate determination. The next section discusses floating, stabilized, and controlled exchange rates in ascending degrees of price manipulation by central banks—more specifically: (1) systems of floating exchange rates, in which the prices of currencies are largely the result of interacting supply and demand forces with varying degrees of stabilizing interference by central banks; (2) systems of stabilized exchange rates (also referred to as “pegged yet adjustable”), whereby the market-determined price of currencies is constrained through central bank intervention to remain within a scheduled narrow band of price fluctuations; (3) systems of controlled exchange rates, in which currency prices are set by bureaucratic decisions.

Although exchange controls are most readily associated with controlled exchange rates, they are actually found in most floating and stabilized exchange rate systems as well—albeit to a much lesser degree. The sweeping deregulation that has engulfed financial systems around the world is certainly marching through the forex market, but has not yet reached its final destination; see Exhibit 7.5 for the map of current exchange rate regimes for the 25 major world economies.

Exhibit 7.5 Exhibit 7.5 Map of Exchange Rate Systems

| Floating | |

| →Clean Float | U.S. dollar, Canadian dollar, Australian dollar, New Zealand

dollar, British pound, Swiss franc, euro, Brazilian real, |

| →Dirty Float | Japanese yen, Korean won, Indian rupee, Mexican peso, Argentine peso,

Malaysian ringgit, Taiwan dollar, Indonesian rupiah, Thai baht |

| →Crawling Peg | Chinese yuan, Vietnamese dong |

| Stabilized | |

| →Basket Peg | Russian ruble ($, €) |

| →Single Currency Peg | CFA Franc Zone pegged to euro,

Saudi rial pegged to U.S. dollar, UAE pegged to U.S. Dollar |

| →Currency Board | Hong Kong Dollar, pegged to U.S. Dollar |

| Controlled | Venezuelan bolivar |

| Burmese kyat | |

Floating Exchange Rates (Clean Float)

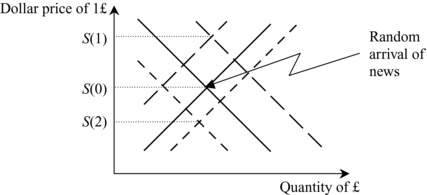

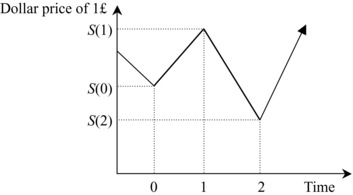

The free interplay of supply and demand for a given foreign currency was shown earlier to determine the rate of exchange at which the market is cleared. This equilibrium exchange rate, however, is unlikely to last for very long: The continuous random arrival of information, such as news about latest inflation statistics, gross domestic product (GDP) growth, oil prices, and so on, will result in a modification of supply and demand conditions as market participants readjust their current needs as well as their expectations of what their future needs will be. Changing supply and demand conditions will, in turn, induce continuing shifts in supply and demand schedules until new equilibrium positions are achieved. As an illustration, fictitious supply and demand curves for British pounds (£) at times (t), (t + 1), and (t + 2) are depicted in Exhibit 7.6. Corresponding equilibrium exchange rates or dollar prices of one pound at times (t), (t + 1), (t + 2), and so on are graphed in Exhibit 7.7.

Exhibit 7.6 Shifts in Supply and Demand Curves

Exhibit 7.7 Oscillating Exchange Rates

Over time, the exchange rate will fluctuate continuously or oscillate randomly around a longer-term trend, very much like the prices of securities traded on a stock exchange or of commodities traded on a commodity exchange.

In the real world, few countries have ever left the prices of their currencies free to fluctuate in the manner just described. For countries whose foreign sector (imports and exports) looms large on their domestic economic horizon, sharply fluctuating exchange rates could have devastating consequences for their orderly economic development.11 Picture, for instance, an industrialized country that imports close to 100 percent of its energy. Abrupt fluctuations in the exchange rate would cause abrupt fluctuations in the price of energy—since energy is a significant input in nearly all economic activities whose prices are denominated in U.S. dollars—and these fluctuations would affect the prices of nearly all finished products. This means that the cost of living index, the purchasing power of consumers, and the real wages of labor would be subjected to abrupt variations.

Managed Floating Exchange Rates (“Dirty” Float)

It is then not surprising that countries that have adopted a system of floating exchange rates have generally resisted the economic uncertainty resulting from a clean float. By managing or smoothing out daily exchange rate fluctuations through timely central bank interventions, they have been able to achieve short-run exchange rate stability (but not fixity) without impairing longer-term flexibility. Such a system of exchange rate determination is generally referred to as a managed or dirty float. It is the system that best approximates the handful of currently floating currencies referred to at the outset of this chapter.

Unlike central bank intervention in a stabilized exchange rate system,12 neither the magnitude nor the timing of the monitoring agency's interference with the free interplay of supply and demand forces is known to private market participants. Furthermore, objectives pursued by central banks through their interventions in the foreign exchange market are not necessarily similar.

Clean versus Dirty Floaters

Who are the “clean” and the “not so clean” floaters? Anglo-Saxon countries, which have a long tradition of low regulation and reasonably unfettered markets, would fall into the (somewhat) clean category; since the mid-1990s the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and alpine Switzerland have resisted intervening in the forex markets. Note that these countries, with the exception of Switzerland, are common-law countries and maritime powers, and have a financial system that tends to be market- rather than bank-centered.

Yet many central banks, such as Korea's and Russia’s, intervene in foreign exchange markets. The largest “dirty” floater is Japan. Between April 1991 and December 2000, for example, the Bank of Japan (acting as the agent of the Ministry of Finance) bought U.S. dollars on 168 occasions, for a cumulative amount of $304 billion, and sold U.S. dollars on 33 occasions, for a cumulative amount of $38 billion. A typical case: On Monday, April 3, 2000, the Bank of Japan purchased $13.2 billion of dollars in the foreign exchange market in an attempt to stop the more than 4 percent depreciation of the dollar against the yen that had occurred during the previous week. As a result of its aggressive interventions to stem too rapid a rise in the value of the yen, Japan's foreign reserves exceeded a trillion dollars for the first time in 2007.

—Adapted from the Federal Bank of New York

Taxonomy of Central Bank Intervention

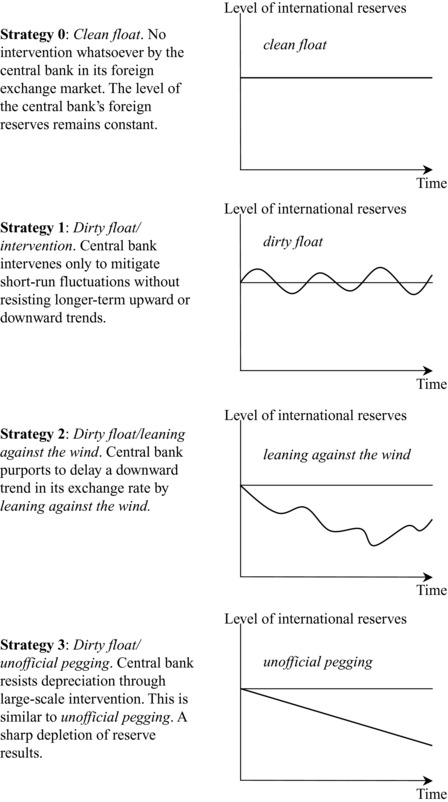

Recent experiences with managed floats have unveiled three major classes of central bank intervention strategies. They can be described as follows:

Strategy 1: At one end of the spectrum would fall countries concerned only with smoothing out daily fluctuations to promote an orderly pattern in exchange rate changes. Clearly, under such a scheme, a central bank does not resist upward or downward longer-term trends brought about by the discipline of market forces.

Strategy 2: An intermediate strategy would prevent or moderate sharp and disruptive short- and medium-term fluctuations prompted by exogenous factors recognized to be only temporary. The rationale for central bank intervention is to offset or dampen the effects of a random or nonrecurring event bound to have a serious, but only temporary, impact on the exchange rate level. That could be the case of a natural disaster, a prolonged strike, or a major crop failure, which would, in the absence of a timely intervention by the central bank in the market, result in a sharp falling of the country's exchange rate level below what is believed to be consistent with long-run fundamental trends. Such a strategy is thus primarily geared to delaying, rather than resisting, longer-term fundamental trends in the market, which is why this strategy is generally dubbed “leaning against the wind.”

Strategy 3: At the other end of the spectrum, some countries have been known to resist fundamental upward or downward movements in their exchange rates for reasons that clearly transcend the economics of the foreign exchange market. For example, in 1994, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York resisted—if only briefly—the yen appreciation beyond the “traumatic” ¥100 = $1 threshold. Such a strategy of so-called unofficial pegging is, in effect, tantamount to a system of stabilized exchange rates that would not define an official par value.

Modus Operandi of Central Bank Intervention

The next question is how central banks actually intervene in the foreign exchange market. So far we have been referring, in a somewhat abstract sense, to official intervention by responsible monetary authorities in their foreign exchange markets without describing the steps that central banks actually take to manipulate exchange rate levels.

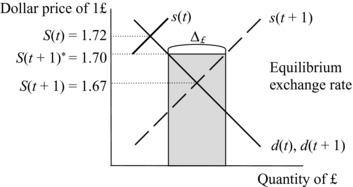

Exhibit 7.8 Modus Operandi of Central Bank Intervention

Official intervention is primarily achieved through central banks’ spot purchases or sales of their own domestic currency, in exchange for the foreign currency whose price they seek to influence. Consider the following case: The Bank of England wants to moderate the depreciation of the pound (see Exhibit 7.8) from 1£ = $1.72 to 1£ = $1.67 that would result from the free interplay of market forces (clean float) over the time interval (t, t + 1). Assume further that the (secret) target level—indicated by an asterisk—at which the central bank wants to maintain its exchange rate is S(t + 1)* = 1.70. From Exhibit 7.8, it can be readily seen that at the target rate of $1.70 to a pound there is an excess supply of (Δ£) or, equivalently, an excess demand of [Δ£ · S(t + 1)*].

Purchasing (Δ £) exchange for the equivalent dollar amount, that is, by supplying the foreign exchange market with [ΔS(t + 1)*]$, the central bank will effectively stabilize at time (t + 1) its exchange rate at $1.70 rather than letting it depreciate to $1.67.13

Moderation of the depreciation of the pound (strategy 2, the “leaning against the wind” type) will result in the Bank of England depleting its dollar reserves. Rigid pegging of the exchange rate at $1.72 through large-scale central bank intervention (strategy 3, the unofficial pegging type) will result in an even steeper rate of depletion of the Bank of England's dollar reserves. In contrast, if the Bank of England limits itself to smoothing out short-run fluctuations (strategy 1) in either direction, its stock of dollar reserves will hover around a constant trend.

Tracking Central Bank Intervention

It is thus possible, on an ex post basis, to ascertain the type of objectives that the central bank pursues by tracking trends in its level of official reserves. Intervention, however, is often concealed by central banks and does not necessarily appear in official international reserve statistics. This may be due to central banks borrowing foreign currencies but reporting only gross, rather than net, reserves. In addition, the profits and losses from intervention in the foreign exchange market are generally buried in balance-of-payment accounts for interest earnings on assets.

The various possible cases are recapitulated in Exhibit 7.9.

Exhibit 7.9 Taxonomy of Central Bank Intervention Strategies

Central Bank Intervention and Market Expectations

Finally, it should be emphasized that central bank interventions have—in addition to an obvious supply-and-demand effect—a continuing impact on market participants’ expectations. Thus, foreign exchange market participants will interpret the clues about central bankers’ attitudes by carefully analyzing the magnitude, timing, and visibility of central bank intervention. Furthermore, action to influence exchange rates is certainly not limited to direct intervention in the foreign exchange market. Equally, or perhaps more, important are domestic money market conditions and movements in short-term interest rates, which exercise a major influence on short-term capital flows that, in turn, will move the exchange rates.

Stabilized or Pegged Exchange Rates

Under a system of stabilized exchange rates, the fundamental economics of supply and demand remain as fully operative as under a system of floating exchange rates. The difference between the two systems lies in the fact that, under a system of stabilized exchange rates, central banks are openly committed not to let deviations occur in their going exchange rates for more than an agreed percentage on either side of the so-called par value.14 This result is achieved through official central bank intervention in the foreign exchange market. The definition of par values, as well as the width of the band of exchange rate fluctuations, have varied across countries and over time. They are taken up in some detail in the balance of this section, which opens with an analytical review of the custodian role of central banks in a system of stabilized exchange rates.

Modus Operandi of Central Bank Intervention with Stabilized Exchange Rates

Consider the case of Malaysia, which pegged its currency, the Malaysian ringgitt (M$), to the U.S. dollar at the fixed rate of M$3.80. Whenever capital inflow or a strong balance of trade surplus pressures the ringgitt to appreciate to, say, M$3.70 = US$1, the central bank would intervene by purchasing the excess dollars flooding the market at the fixed rate of M$3.80. We now turn to a review of current institutional implementations and variants of this general scheme of stabilized exchange rates.

Monthly Average Exchange Rates: Chinese Renminbi per U.S. Dollar

China's yuan was tightly pegged to the U.S. dollar at yuan 8.28 = $1 from 1997 to July 21, 2005. Over the period China sailed remarkably unscathed through the Asian financial crisis of July 1997 while growing at the astounding rate of better than 10 percent per year. How was China able to withstand the Asian financial crisis? To a large degree China—unlike its Asian neighbors—kept tight exchange controls on capital account transactions, which limited the mobility of short-term capital in and out of China.

On July 21, 2005, the People's Bank of China (China's central bank) announced that it was “reforming the exchange rate system by moving into a managed floating exchange rate regime based on market supply and demand with reference to a basket of currencies. The Yuan will no longer be pegged to the U.S. dollar. … The exchange rate of the U.S. dollar against the Yuan will be adjusted to 8.11 Yuan per U.S. dollar. … The daily trading price of the U.S. dollar against the Yuan will continue to be allowed to float within a band of +/–0.3 percent around the central parity published by the People's Bank of China.”

—Professor Werner Antweiler, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Pegging to an Artificial Currency Unit (Mid-1970s to the Present)

When the world's major currencies began to float independently in early 1973, most small countries initially continued to peg their currencies to the single reserve currency that they had previously used to stabilize their exchange rates (mainly the U.S. dollar, British pound, and French franc). However, the benefits of single-currency pegging were soon overshadowed by the costs of exchange rate fluctuations against other major currencies, especially as the single reserve currency such as the U.S. dollar or British pound became prone to prolonged over-/undershooting against other major trading currencies. Consequently, a number of countries began to manage their exchange rates systematically against key trading partners’ currencies; this could be greatly facilitated by pegging the home currency to a basket of currencies—the so-called artificial currency unit (ACU) (e.g., the European Currency Unit [ECU, 1979–1999], which became the euro, or the special drawing right [SDR] issued by the International Monetary Fund—whose composition would typically reflect the country's bilateral trade flows pattern. Indeed, a great many countries have abandoned a single-currency pegging in favor of pegging against a currency basket of their own choosing).

DERIVATIVES AND THE PRIVATIZATION OF FOREX RISK MANAGEMENT

The breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of quasi-fixed exchange rates and the subsequent advent of volatile exchange rates ushered the world financial system into a new era of deregulation and financial innovation, with the introduction of currency futures, options, swaps, swaptions, and other products. As early as 1972, currency futures started to trade at the newly established International Monetary Market (IMM, a subsidiary of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange). Soon the deregulation of interest rates in the United States set in motion the introduction of interest rate derivatives, which eventually would dwarf currency and commodity derivatives. When the world became a riskier place, firms and financial institutions naturally sought safe harbors in the form of hedging with financial derivatives. With protection against volatile exchange rates no longer provided free of charge by their central banks, forex market participants resorted to private-sector solutions by engineering new insurance products, also known as derivatives. In a sense, risk mitigation had been privatized!

Indeed, derivatives are sophisticated instruments whose spiraling success over the years has largely been driven by increased price volatility in commodities, currencies, and interest rates. Derivatives facilitate efficient risk transfer from firms that are ill-equipped to bear risk and would rather not be exposed to risk to firms that have excess risk-bearing capacity and are willing to take on exposure to risk. Thanks to derivatives, risk transfer has become far more precise and efficient as its cost plunged because of breakthroughs in computer technology and financial theory. Thus derivatives allow for economic agents—households, financial institutions, and nonfinancial firms—to avail themselves of the benefits of division of labor and comparative advantage in risk bearing: But are derivatives, indeed, adequate instruments for risk avoidance and value creation? Shouldn't the major derivatives-linked disasters that are striking some of the best-managed firms in the world with predictable frequency be construed as evidence of wealth destruction rather than wealth creation? Let's now turn to the specific types of firms’ exposure to foreign exchange risk before reviewing how forwards, futures, and options can be harnessed for hedging forex risk.

Transaction Risk

In the early phases of internationalization, firms are primarily exposed to foreign exchange risks of a transactional nature. Firms that are actively involved in exporting will find it necessary, for competitive reasons, to invoice accounts receivable in the currency of the buyer. Similarly, firms actively sourcing components or finished products and services from foreign companies may have to accept to be invoiced in the currency of the supplier. In other words, their accounts payable would be in a foreign currency. Either way, whether a firm buys or sells goods in a foreign currency, sizable exchange losses may be incurred from unforeseen and abrupt exchange rate movements. These currency fluctuations can wipe out profits on export sales or eliminate cost savings on foreign procurement.

Transaction Exposure in the Trading Room: Citibank Forex Losses15

We are periodically reminded of the “treachery” involved in measuring—let alone managing—transaction exposure in the forex “trading room.” The recent (January 2008) $7.5 billion loss incurred by the almighty Société Générale at the hands of a junior trader, because of unchecked speculation on DAX and Euro Stoxx futures, is only the latest incident.

Witness how Citibank incurred an $8 million loss in June 1965, the heyday of the supposedly tranquil Bretton Woods system of pegged exchange rates. A Belgian trader, working on salary rather than commissions, elaborated a sophisticated speculative scheme based on his conviction that the pound sterling would not be devalued from its par value of $2.80 against the U.S. dollar, in spite of mounting balance of payments pressure to do so.

As early as September 1964, the trader started to accumulate long (asset) sterling positions at a significant forward discount, betting that the spot pound would remain within the range of $2.78–$2.82. Since traders are expected to report “square” positions of all outstanding forward contracts at the end of the trading day, the long sterling position had to be disguised by entering into a string of short-term forward sale contracts. Unfortunately, the short-term contracts were maturing at a loss (cash outflow) that ultimately exposed the scheme to senior managers, who hurriedly, and mistakenly (as it turned out), liquidated the long sterling positions before maturity at a large loss.

Square positions, by netting asset and liability positions regardless of maturity, hide deceptive speculative positions. Back-office operations are advised to maintain independent and unforgiving scrutiny of any transactions that are cleared for the front-office traders.

Translation Risk

Multinational corporations are required to report their worldwide performance to their shareholders on a quarterly basis in the form of simple statistics—consolidated earnings and the much awaited and closely studied earnings per share (EPS). This periodic translation process will lead to exchange losses or gains.

Pressures from a somewhat myopic investment community on multinational corporations to more fully disclose and account for exchange losses (or gains) are clearly compelling treasurers to pay close attention to translation risk. Accordingly, the suboptimal objective of smoothing the pattern of consolidated earnings between accounting periods tends to substitute itself for the sounder one of net cash flow maximization. Is it a good idea?

At the core of the translation risk hedging debate is the fact that translation losses or gains—however large they may be—are unrealized noncash flows in nature and without tax implications. Yet we know that value creation is driven by cash flows—not by accounting profits. Is it then legitimate for sophisticated multinational corporations to concern themselves with translation exposure hedging? It would seem that such activity is, at best, an attempt to deceive investors through accounting gimmickry rather than being motivated by value creation, unless it can be shown that hedging translation exposure by modifying/lowering the risk profile of the firm is, indeed, resulting in higher stock prices, which in turn lowers the cost of equity capital. In capital markets that are truly efficient that will not be the case. In financial markets that are not quite fully efficient, investors will reward firms that are producing smoother earnings streams. In this case, hedging translation exposure is value creating. There are two special situations where hedging translation exposure will have more direct cash flow implications:

1. Loan covenants. If the firm has to satisfy a loan covenant that requires that a threshold metric, such as debt-to-equity ratio, not be crossed because of unchecked translation losses to the cumulative translation losses account, then direct cash flow implications may result in the form of a higher cost of debt. Failure to meet such loan covenants may lower or reduce the firm's credit rating or its borrowing capacity, or force it to renegotiate lending conditions at less favorable terms.

2. Credit rating. A debt-to-equity ratio unduly impacted by a string of translation losses may result in a firm's debt rating being downgraded and therefore an increased cost of debt financing.

After reviewing the long-established forward contract, we turn next to a detailed review of forex derivatives, which have been engineered since 1971.

Forward Contracts

A forward exchange contract is a commitment to buy or sell a certain quantity of foreign currency on a certain date in the future (maturity of the contract) at a price (forward exchange rate) agreed upon today when the contract is signed. Clearly it is important to understand that a forward contract, when signed, is an exchange of irrevocable and legally binding promises (with no cash changing hands), obligating the two parties to go through with the actual transaction at maturity and deliver the respective currencies (or cash settlement) regardless of the state of the world—that is, regardless of the spot exchange rate at the time of contract settlement. Forward exchange contracts had been available for decades, but it was not until the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, and the resulting heightened volatility in currency prices, that new foreign exchange risk management products started to appear. Futures contracts on foreign exchange were first introduced in May 1972, when the International Monetary Market of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange began trading contracts on the British pound, Canadian dollar, Deutsche mark, Japanese yen, and Swiss franc.

Currency Futures

A currency futures contract is traditionally defined as a legally binding agreement with an organized exchange to buy (or sell) today a set amount of foreign currency for delivery at a specified date in the future. As such, a currency future does not appear terribly different from the old-fashioned forward contract, except for the fact that such contracts are entered into with organized (and generally regulated) exchanges—a fact that has far-reaching implications for credit risk (counterparty risk). There are, however, a number of additional differences between futures and forwards, which we address next.

Contract Standardization

To promote accessibility, trading, and liquidity, futures contracts specify a standardized face value, maturity date, and minimum price movement. Consider, for example, the euro (€) futures contract as traded on the International Monetary Market (IMM) of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange: It specifies a standardized face value of €125,000 with delivery date set for the third Wednesday of March, June, September, or December, as well as the minimum price movement, or tick size, which is set at $12.50 per contract (or $0.0001 per €). On December 1, 2009, the March 2010 contract closed at $1.4715 per €. By contrast, the reader will recall that forwards are tailor-made contracts negotiated directly by the two parties involved, with the amount transacted starting at $1 million and maturity dates generally stretching in multiples of 30 days.

Marking-to-Market and the Elimination of Credit Risk

In order to minimize the risk of default (counterparty risk), a futures exchange such as the IMM takes at least two precautionary measures for every contract it enters into: (1) it requires the buyer to set up an initial margin (a surety bond of sorts) that, at the minimum, should be equal to the maximum allowed daily price fluctuation; and (2) it forces the contract holder to settle immediately any daily losses resulting from adverse movement in the value of the futures contract. This is the practice of forcing the contract holder to a daily marking-to-market, which effectively reduces credit risk to a daily performance period with daily gains/losses added/subtracted from the margin account. To avoid a depleted margin account (which essentially means that the surety bond has become worthless), the futures trader is obligated to replenish his or her margin account (so-called margin call) should it fall below a preset threshold known as the maintenance margin. One practical question is, of course: How are the initial margin and the maintenance margin determined? The initial margin should protect the clearinghouse against default by the futures contract holder, and will therefore well exceed the maximum daily allowance; but ultimately it will be on a case-by-case basis reflecting, in part, historical volatility of the currency price—let's say 5 percent of the face value of the contract or 0.05 × €125,000 = $6,250. The maintenance margin typically would be set as a percentage of the initial margin—let's say 75 percent of $6,250 = $4,687.

Currency Option

A currency option gives the buyer the right (without the obligation) to buy (call contract) or to sell (put contract) a specified amount of foreign currency at an agreed price (strike or exercise price) for exercise on the expiration date (European option) or on or before the expiration date (American option).16 For such a right, the option buyer/holder pays to the option seller (called the option writer) a cash premium at the inception of the contract. A European option whose exercise price is the forward rate is said to be an at-the-money option;17 if it is profitable to exercise the option immediately (disregarding the cash premium), the option is said to be an in-the-money option; and conversely, if it is not profitable to exercise the option immediately, the option is said to be an out-of-the-money option. As expected, in-the-money options command higher premiums than out-of-the-money options. When held to maturity, the option will be exercised if it expires in-the-money and abandoned when it expires out-of-the-money. Currency options can be negotiated over-the-counter with features (face value, strike price, and maturity) tailor-made to the special needs of the buyer, who is responsible for evaluating the counterparty risk (that is, the likelihood of the option writer delivering if the option is exercised at maturity). Of practical interest is the trade-off between strike price and premium: The further in-the-money the strike price is, the more expensive the option becomes (i.e., the higher the premium), and conversely, the further out-of-the-money, the less expensive it is. Standardized option contracts available from organized exchanges such as the Philadelphia Stock Exchange are practically devoid of counterparty risk, since a well-capitalized clearinghouse18 serves as a guarantor of the contracts; however, the option buyer is limited to a relatively small set of ready-made products directly available off the shelf.

Options Strategies

There are many speculative options strategies, ranging from the simple (e.g., writing covered options) to more complex strategies known under such colorful names as straddle, strangle, butterfly, condor, and bull price spread, to name a few. After reviewing the mechanics of writing covered options, this section considers the straddle strategy, whose payoff at expiry depends on the volatility, rather than on the absolute level, of the exchange rate.

Writing Covered Options

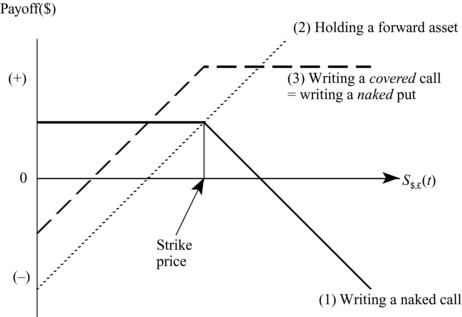

By writing naked (uncovered) call options on sterling, one clearly speculates by accepting an up-front payment (premium) in exchange for a potentially unlimited loss if sterling were to appreciate against the dollar. (See line 1 in Exhibit 7.10.) It would stand to reason that if the call option writer were to hold a forward asset position in sterling (Exhibit 7.10, line 2), the writer would have effectively covered the selling of a naked call option—hence the reference to writing a covered call option. In fact, this is misleading, since a covered call option is nothing more than writing a naked put option on sterling, as illustrated in Exhibit 7.10 by line 3, which is constructed as the algebraic sum of lines 1 and 2.

Exhibit 7.10 Writing a Covered Call Option

Exhibit 7.11 Buying a Straddle

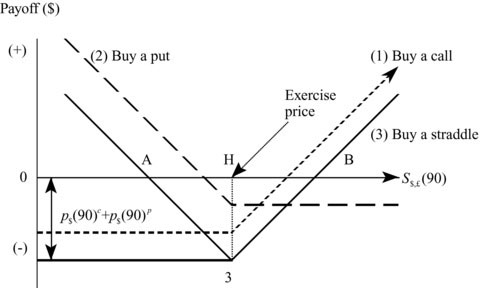

Options Straddles

A straddle is defined as the simultaneous purchase of put and call options of the same strike price and maturity. This strategy is especially attractive when one anticipates high exchange rate volatility but is hard-pressed to forecast the direction of the future spot exchange rate. Exhibit 7.11 superimposes the purchase of a 90-day call option (line 1) on the purchase of a 90-day put option (line 2) at the same strike price, denoted here by E(90), to create a straddle (line 3, which appears as a V in the graph of the algebraic sum of lines 1 and 2). Of interest are the break-even exchange rates (labeled A and B in Exhibit 7.11), which are symmetrical vis-à-vis the strike price, with:

![]()

and:

![]()

where p(0)c and p(0)p are the premium paid on the call and put options, respectively.

If the future spot rate S(90) turns out to be very volatile and escapes the AB band, the straddle will be profitable, as shown by the positive portion of line 3 in Exhibit 7.11. Conversely, if the exchange rate were to move within the narrow AB range, the buyer of the straddle may lose as much as p(0)c + p(0)p which, graphically, is the line segment H3, also equivalent to ½ the length of line AB. Importantly, this is the most the buyer could lose.

Inversely, the writer (seller) of a straddle bets on low volatility of the end exchange rate by writing both put and call options with the same exercise price. However, were this bet to be wrong, the writer's loss would be unlimited. The most that the writer would stand to gain would be the sum of the two option premiums sold.

Exhibit 7.12 International Put-Call Parity

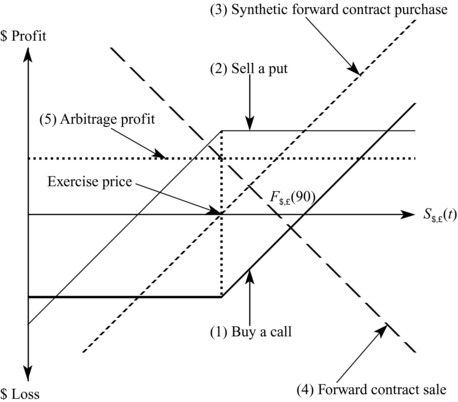

Put-Call Forward Parity Theorem

We now turn to the powerful arbitrage relationship that binds the options market to the forward exchange market. A 90-day forward purchase contract can always be replicated by simultaneously buying a 90-day call option and selling a 90-day European put option at the same strike price, E(90). Superimposing put and call options in Exhibit 7.12 shows that for the call option holder the unlimited portion of the profit function (adjusted correspondingly by the option premium) is equivalent to the unlimited profit portion of the foreign currency forward purchase contract—or, conversely, the unlimited loss portion of the same forward purchase contract corresponds to the unlimited loss of the put option writer (similarly adjusted by the option premium). Thus, in the option market it is easy to create synthetic forward contracts whose prices can be readily compared to prevailing rates in the forward market. This fundamental equivalence between the option and forward markets drives the constant arbitrage activity between the two markets and is known as the put-call forward exchange parity.

By combining the purchase of a call option (Exhibit 7.12, line 1) with the writing of a put option (Exhibit 7.12, line 2) at the same exercise price, E(90), one effectively purchases forward the foreign currency at the options’ exercise price (Exhibit 7.12, line 3, which is the graphical sum of lines 1 and 2). The same amount of foreign currency can be immediately sold on the forward market at the forward rate of F(90) (Exhibit 7.12, line 4). However, the synthetic forward contract created by buying a call and selling a put at the same strike price will cost the difference between the premium p(0)c paid for buying the call and the income generated from writing the put, p(0)p. Accounting for the fact that this difference is paid (received) when the option contract is entered into rather than exercised, the total cost or terminal value of buying synthetically the foreign currency forward is:

(7.1) ![]()

where ius is the interest rate over the 90-day period. Thus, by buying the currency synthetically at the price given by Equation 7.1 and selling it at the prevailing forward exchange rate of F(90), the arbitrageur is generating a risk-free profit of:

(7.2) ![]()

Allied-Lyons's Deadly Game19

Allied-Lyons—better known for its tea bags than for its forays into the currency market—announced a stunning $269 million forex loss (approximately 20 percent of its projected profits for 1991). Facing a sluggish economy, its treasury had elaborated a sophisticated scheme that gambled not so much on the absolute level of the dollar/sterling rate as on its volatility. This gamble was achieved through a combination of currency options known as straddles and strangles that in this particular case would have produced profits had the exchange rate turned out to be less volatile than the option premium implied.

This ingenious scheme was elaborated at the beginning of the Gulf War when the relatively high price of option premiums (due to heavy buying from hedgers) convinced Allied-Lyons that it was propitious to place an attractive short-term bet that volatilities would decrease as soon as hostilities started. Thus Allied-Lyons wrote deep-in-the-money options in straddle/strangle combinations, thereby netting hefty cash premiums. However, when the allies launched their air offensive, the initial uncertainty as to the outcome did not reduce the option volatility—at least not soon enough for Allied-Lyons to see its speculation gambit succeed. Indeed, it took another month for the ground offensive to appease the forex market, by which time it was already too late for Allied-Lyons, which had been forced by its bankers to liquidate its options position at a great loss.

shown as line 5 (line 3 plus line 4) in Exhibit 7.12. This disequilibrium will set arbitrage forces into motion as the price of the call option is bid up and the price of the put option is bid down, until the risk-free profit disappears and parity prevails. As arbitrageurs construct synthetic forward purchase contracts, its rate will be driven up. Simultaneously, by selling at the higher prevailing forward rate, arbitrageurs will depress the price of forward contracts, F(90), thereby forcing inequality 7.2 toward equality.

Zero-Premium Options

The limitation of the forward contract is that while it gives 100 percent protection against an adverse movement in the future exchange rate, it also eliminates any opportunity for gain from a subsequent movement in the exchange rate; such a potential missed gain is generally referred to as an opportunity cost. Currency options, in contrast, allow full participation in this upside potential, though at a substantial up-front cash flow cost that discourages many would-be users. Of the many forex derivative products that have appeared recently, two products that allow participation in those potential gains—without incurring the up-front cash expenses—are of particular interest to corporate treasurers: (1) forward range agreements and (2) forward participation agreements. Both products are based on the simple idea of combining writing an option whose premium finances the purchase of another option so as to create, when superimposed on the underlying naked exposure, the desired risk profile.

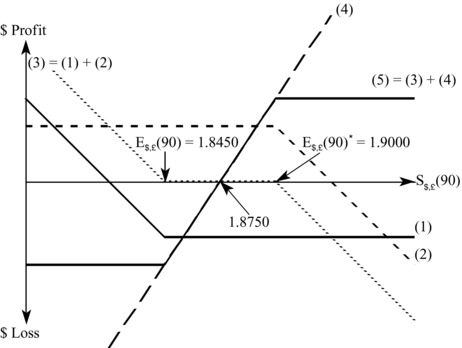

Forward Range Agreements and Currency Collars

Like forwards, forward range contracts will lock in a worst-case exchange rate; unlike forwards, though, forward range contracts allow the hedger the opportunity to benefit from an upside market move delineated by a range of forward rates. Assuming an underlying sterling asset position a(90), the user would structure a sterling forward range agreement by first buying, for example, a sterling put option at a strike price of E(90) = 1.8450 (the defensive option is represented by line 1 in Exhibit 7.13) while offsetting all of the up-front cost by selling a sterling call option at a strike price of E(90)* = 1.9000 (the financing option is represented by line 2 in Exhibit 7.13).20 Note, however, that the financing option will bound the upside potential of the defensive option resulting from a favorable currency move. Typically, the user will set an exercise price E(90) lower than the forward rate at which the user is buying the put option while selling a call at an exercise price E(90)* > E(90) so that the premium received from the call option p(0)* equals the premium paid on the put option p(0). By entering into such a contract, the user would lock in the worst-case exchange rate, E(90), while retaining the opportunity to benefit from a sterling appreciation favorable to the underlying sterling asset position (Exhibit 7.13, line 3). Thus the risks of an open foreign exchange position are eliminated, while the magnitude of opportunity is limited to the top of a range E(90)*. Typically, a forward range contract is defined as a range E(90), E(90)* bracketing the forward exchange rate F(90) and thereby establishing a tunnel within which the hedger accepts the exchange risk exposure, but outside of which the hedger is protected or restricted by the lower/upper bound of the range. The resulting risk profile is represented by line 5 in Exhibit 7.13, which is the graphical sum of lines (1) + (2) + (4) = (5). As can be seen in the exhibit:

- If the actual end-of-the-period exchange rate falls below the protection level E(90), the user will exercise the put option and sell sterling at E(90).

Exhibit 7.13 Forward Range Agreement

- If the actual end-of-the-period exchange rate falls within the protection range E(90), E(90)*, the user will benefit from the actual spot exchange rate S(90) and receive a(90)S(90).

- If the actual end-of-the-period exchange rate exceeds the upper bound of the range E(90)*, the user is limited to receiving a(90)E(90)* as the call option is exercised by the bank that sold the forward range contract.

In a currency collar, the hedger is willing to pay a reduced premium (as opposed to a zero premium in the case of a forward range agreement) to enjoy a wider range, E(90), E(90)*, or greater profit potential. This is achieved by writing a defensive call option that generates less premium income; that is, it does not fully finance the purchase of the put option.

Forward Participation Agreements

This type of protection contract shares certain characteristics with the forward range agreement in that there is no up-front fee and the user has the flexibility to set the downside protection level. However, unlike the forward range agreement, where the maximum opportunity gain is capped at a prearranged level, the forward participation agreement allows its user to share in the upside potential by receiving a fixed percentage (the participation rate) of any favorable currency move irrespective of magnitude. The user will purchase a put option whose premium p(0)p is partially financed by writing a call option, thereby generating a net revenue of p(0)c – p(0)p. Instead of restituting the difference, p(0)c – p(0)p, the bank allows the user to partake in the upside potential to the tune of α percent. Specifically, the downside protection level is tied to the participation rate, to be negotiated with the bank:

- If the actual exchange rate falls below the protection level E(90), the user will exercise the put option.

- If the actual exchange rate exceeds the protection level, S(90) > E(90), the user will participate [participation rate α is a function of the level of E(90)] and receive a rate of:

As hinted in the introduction, financial engineering has shown tremendous ingenuity in the past decade, with far too many exotic options to include in the present chapter.

The forex market also has undergone major changes over the past decade. The interbank market has largely evolved from direct/bilateral dealing and voice brokering to electronic trading via Internet-based deal-matching systems. As a result, the microstructure of the forex market is less fragmented and points toward greater transparency, as the price discovery process is faster thanks to powerful electronic price-aggregator platforms. Similarly, the macroeconomics of the forex market points toward a lesser role for central banks due to reduced intervention in currency markets, more flexibility in exchange rates, and greater convertibility for many currencies. As central banks disengaged themselves from the risk mitigation business, the private sector filled the gap by engineering derivatives, enabling market participants to transfer among themselves exposures to forex risk in an increasingly efficient manner.

NOTES

1. Foreign exchange derivative products, in the form of currency futures and options, are also traded as standardized products on organized exchanges such as the International Money Market (IMM) in Chicago. See the last section of this chapter for further discussion.

2. The forward rate is agreed upon today and binding 60 days later when the sale is consummated regardless of what the spot rate may be on that day. The forward rate is set according to the interest rate parity formula.

3. Buy side refers to consumers and sell side to merchants. The buy side would, for example, purchase euros (selling dollars) while the sell side is selling euros (buying dollars). Because of the nature of forex trading, both buy and sell sides are buying one currency and selling the other.

4. See Bank for International Settlements (2001) and Rime, Dagfinn (2003).

5. Market makers are dealers—generally based at bank trading desks—ready to quote buy and sell prices on request. The market maker provides liquidity to the market and is compensated by the spread between buy and sell rates.

6. Voice brokers used to work through closed telephone networks, whereas electronic brokers today use Reuters D3000 or EBS.

7. Reuters introduced the Reuters Market Data Service (RMDS) as early as 1981, which allowed for the exchange of information over computer screens but no actual trading. In 1989 Reuters Dealing 2000-1 replaced RMDS and allowed computer-based forex trading, displacing telephone (and human) trading. The platform was updated in 1992 with Reuters D2000-2 and again in 2006 with Reuters D3000.

8. To counter the dominance of Reuters, the Electronic Broking System (EBS) was created in 1993 by a consortium of large banks—ABN Amro, Bank of America, Barclays, Chemical Bank, Citibank, Commerzbank, Credit Suisse, Lehman Brothers, Midland, J.P. Morgan, NatWest, Swiss Bancorp, and Union Bank of Switzerland.

9. In 1974 the default of Bankhaus Herstatt sent shock waves through the foreign exchange market, giving new meaning to counterparty and settlement risk.

10. See section on forex trading.

11. This is particularly the case in a smaller developed country, such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, or New Zealand, whose foreign sector often accounts for over 30 percent of gross national product (GNP).

12. Central bank intervention within the context of stabilized exchange rates is discussed at some length in the following section (see Dominguez, Kathryn M., and Jeffrey Frankel, 1993). It essentially results from a public commitment to maintain exchange rate variations within a narrow band of fluctuations whose ceiling and floor are unambiguously known to market participants (see Mayer, 1974).

13. The reader will remember that the supply curve of £ is nothing other than the demand curve for $. Similarly, the demand curve for £ is the supply of $.

14. Official exchange rate prevailing between a given currency and the dollar.

15. See Chapter 3 in Jacque (2010).

16. The terminology of the American or European option does not refer to the location where the option contract is traded. Both European and American option contracts are traded on both continents, as well as in the Far East.

17. American options’ exercise prices are generally compared to the spot rate (rather than forward rate), with similar definitions of at-, in-, or out-of-the-money applicable since they can be exercised immediately.

18. The clearinghouse is the Option Clearing Corporation (OCC), which also clears exchange-traded equity options. OCC is jointly owned by all U.S. equity options exchanges.

19. See Chapter 8 in Jacque (2010).

20. By necessity, such products require European options.

REFERENCES

Bank for International Settlements. 2001. “The Implications of Electronic Trading in Financial Markets.” (January). www.bis.org/publ/cgfs16.htm.

Bank for International Settlements. 2007. “Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Derivatives Market Activity in 2007.” www.bis.org/publ/rpfxf07t.htm.

Dominguez, Kathryn M., and Jeffrey Frankel. 1993. Does Foreign Exchange Intervention Work? Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

Holmes, A. R., and F. H. Scott. 1965. The New York Foreign Exchange Market. Federal Reserve Bank of New York: New York.

Jacque, Laurent L. 2010. Global Derivative Debacles: From Theory to Malpractice. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co.

Kubarych, Roger M. 1983. Foreign Exchange Markets in the United States, 2nd ed. New York: Federal Reserve Bank.

Lyons, R. K. 2001. The Micro-Structure Approach to the Foreign Exchange Market. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mayer, Helmut W. 1974. “The anatomy of official exchange rate intervention systems.” Essays in International Finance 104. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Rime, Dagfinn. 2003. “New electronic trading systems in foreign exchange markets.” In Derek C. Jones, ed. New Economy Handbook, Chapter 21. Salt Lake City: Academic Press.

Root, Franklin R. 1994. International Trade and Investment. 7th ed. Cincinnati: South Western Publishing.

Sarno, Lucio, and Mark P. Taylor. 2001. “The Microstructure of the Foreign Exchange Market: A Selective Survey of the Literature.” Princeton Studies in International Economics, 89 (May).

Taylor, Dean. 1982. “Official Intervention in the Foreign Exchange Market; or, Bet Against the Central Bank.” Journal of Political Economy 90:2 (April), 356–368.