Chapter 10

Securitized Products

INTRODUCTION

Securitization is defined as a sale of assets to a bankruptcy-remote special purpose entity with a concurrent sale of interests in the entity in the capital markets. The most basic objective of a securitization is to separate the credit risk of the originator of assets from the credit risk inherent with the assets. The bankruptcy-remote special entities are called special purpose entities (SPEs) or special purpose vehicles (SPVs). The interests in such entities that are sold in the capital markets are known as asset-backed securities (ABS). Securitization began in the 1970s when government agencies issued securities backed by home mortgages. Later, commercial mortgages, credit card receivables, auto loans, student loans, and many other financial (and, later, nonfinancial) assets were securitized. While securitization itself is just a few decades old, its roots lie in an age-old practice of collateralized borrowing.

Securitization is focused on legal isolation of assets and is a legal technique at its core. However, we will not address legal or tax aspects of securitization in this chapter. Instead, we will focus on the structuring and analytical aspects of transactions, as well as market history and trends. In a number of cases, we will rely on numerical examples to illustrate key concepts. We will use simplified examples with a deliberate goal of forging broad intuitive understanding of securitization.

ORIGINS OF SECURITIZATION

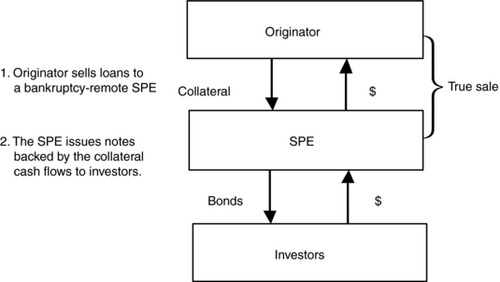

The use of securitization as a financing tool has grown rapidly since its inception. In its most basic form, securitization is simply a legal technique for isolating assets from the originator of those assets or from their current owner. In a securitization, the assets are transferred to a special purpose entity (SPE) in such a way that the legal ownership of the assets is transferred from the original owner to the SPE (see Exhibit 10.1). The SPE then issues ABS (also known as asset-backed bonds or asset-backed debt) backed solely by the collateral it owns. This allows investors to analyze the credit quality of the securitized assets separately from the credit quality of the originator, making risks relatively transparent.

Exhibit 10.1 Simplified Diagram of a Securitization

Under this arrangement, if the originator were to file for bankruptcy, its creditors would have no claims on the assets in the SPE. Similarly, if the cash flows generated by the collateral are insufficient to pay back all the ABS investors, they do not have a claim on the originator. This bankruptcy remoteness is the heart of the securitized products market.

MARKET SIZE AND SEGMENTS

Asset-backed securities are often categorized by collateral asset types. It is customary to subdivide the market into two broad segments: mortgage-backed securities and asset-backed securities.

Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) include U.S. government agency issues: the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA, Ginnie Mae); the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA, Fannie Mae); and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC, Freddie Mac); as well as securities backed by pools of nonconforming high-grade residential mortgages. Commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) are backed by mortgage loans related to commercial properties. Commercial mortgage-backed securities are often included within the MBS category for the purposes of market statistics. Over the past two decades, the size of the MBS market has outpaced the size of the U.S. Treasury market as well as the size of the U.S. corporate debt market. According to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), outstanding MBS was in excess of $9.2 trillion as of Q2 2009. The size of the market has nearly tripled since 2000.

Asset-backed securities (ABS) include bonds backed by a wide variety of collateral types. Most common collateral types include credit card receivables, auto loans and leases, student loans, equipment leases, dealer floor plan loans, and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). It is customary to include securities backed by subprime mortgage loans in the ABS category, rather than grouping the subprime with MBS. In part, this underscores the consumer credit nature of this product as opposed to its housing-related character. Boat loans, consumer lines of credit, manufactured housing loans, motorcycle loans, subprime auto loans, aircraft leases, railcar leases, recreational vehicle loans, small business loans, truck loans and leases, franchise loans, lottery awards, rental car fleet leases, franchise and pharmaceutical royalties, stranded cost receivables, tax liens, and time-share loans are among the less common ABS collateral types. According to SIFMA, total outstandings of the U.S. ABS market grew from about $1 trillion in 2000 to $3.65 trillion as of Q3 2009. In the first half of 2010, new ABS issuances in the United States totaled $64.8 billion.1 ABS issuance volume peaked in 2006 at $753.9 billion. Since 2006, issuance volume has steadily declined, primarily driven by the decline in issuance of subprime mortgage ABS.

Key Parties

Each securitization is comprised of various parties that are involved in the transaction. (See Exhibit 10.2.)

Exhibit 10.2 Key Parties to a Securitization

| Key Party | Description |

| Issuer/Trust | Legal entity that issues the securities to investors. The sole obligor of the liabilities that are created by the securitization. |

| Seller/Originator | The entity that originates and/or sells the underlying receivables that are securitized. |

| Transferor | A bankruptcy-remote entity required between the seller/originator and the SPE in order to protect the receivables from the originator's insolvency and to characterize the transaction as a true sale for legal (bankruptcy) purposes. |

| Servicer | An entity that is responsible for servicing the receivables pursuant to its standard servicing and collection procedures. |

| Indenture Trustee | Trustee for the ABS note holders. |

| Rating Agencies | The nationally recognized statistical rating organizations that assign debt ratings to the securities that are issued by the SPE. |

SPE Sources and Uses of Funds

The SPE or SPV can be viewed as an ongoing business entity that has various sources of funds that are used to pay its obligations.

Excess spread (the funds remaining after payment of the SPE's operating expenses and debt service expenses) forms the first layer of credit protection. Excess spread is normally used to:

- Pay down the securities, thereby creating overcollateralization (the amount by which the balance of the receivables exceeds the balance of securities).

- Pay down the securities to eliminate collateral deficiency caused by losses experienced by the collateral pool (i.e., eliminate negative overcollateralization).

- Fund a reserve account until it reaches a specified level.

See Exhibits 10.3 and 10.4.

Exhibit 10.3 Sources of Funds of a Securitization

| Sources of Funds | Description |

| Scheduled payments on the receivables | Scheduled interest and principal collections. |

| Prepayments on the receivables | Full or partial prepayments. |

| Servicer advances | Advances made by the servicer with respect to delinquent receivables. These “loans” are made only to the extent the servicer expects to be repaid from subsequent payments. |

| Liquidation proceeds | Any proceeds received on a defaulted receivable, including insurance proceeds and sale proceeds from the disposition of collateral. |

| Amounts on deposit in reserve account | The reserve account can be funded from a deposit by the seller and/or excess spread and is used to cover shortfalls in the SPE's available funds needed to pay interest and principal on the securities. |

| Other | In a transaction that involves assets other than loans, a SPV's assets may generate rental payments, royalties, lottery winnings, and so on. |

Exhibit 10.4 Uses of Funds of a Securitization

| Use of Funds | Description |

| Servicing fee | Fee paid to the servicer as compensation for administering and servicing the assets. |

| Reimbursement of servicer advances | Repayment of previous liquidity advances made by servicer. |

| Interest payments | Interest due on securities. |

| Principal payments | Repayment of the principal amount of the securities. |

| Deposits to the reserve account | Funds required to be deposited into the reserve account if its balance is below the required level. |

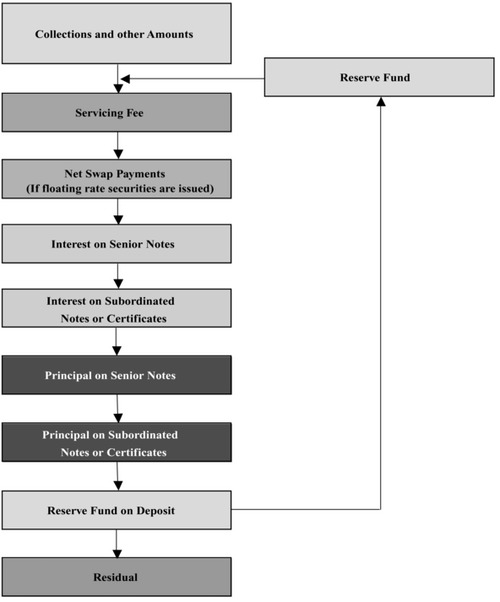

Funds get allocated based on a predefined priority of payments, also known as a cash flow waterfall. Exhibit 10.5 illustrates a basic waterfall of a hypothetical auto loan securitization.

Exhibit 10.5 Simplified Cash Flow Waterfall

Credit Enhancement

Credit enhancement is required to achieve the desired rating on the securities. As discussed later in more detail, the rating agencies work with a number of cash flow scenarios, in which they stress defaults, prepayments, and a number of other factors to determine the required enhancement level consistent with the desired rating.

Credit enhancement for a basic ABS transaction may take several forms:

- Excess spread.

- Cash reserve account (initial deposit or built from excess spread).

- Overcollateralization (initial deposit or built from excess spread).

- Subordination of principal.

These methods of enhancing a transaction can be used in combination to achieve the desired transaction characteristics.

Excess Spread

If the interest rate earned on a loan pool is greater than that owed to pay ABS bondholders and servicing fees, the excess is generally available to cover losses on the collateral.

Cash Reserve Accounts

Cash reserve accounts are conceptually the simplest form of enhancement. Generally, cash reserve accounts are utilized in combination with subordination or overcollateralization in most automobile loan ABS structures. The cash portion of the enhancement is required by the rating agencies to address liquidity concerns. Cash is deposited into the reserve account by the seller and/or built up over time by depositing excess spread into the account. In most cases, losses on the receivables in excess of the excess spread and any overcollateralization are reimbursed from draws on this account in order to protect the note holders from loss. Cash in the reserve account is generally restricted by the rating agencies to liquid, highly rated eligible investments such as A-1+/P-1 commercial paper. Since the rate earned on these investments is low relative to the seller's cost of capital, the seller experiences negative carry (i.e., the difference between the rate earned and the cost of capital) on the balance in the reserve account. As a result, efficient structures seek to minimize the cash reserve account requirements.

Overcollateralization

Overcollateralization is defined as the excess of the collateral pool balance over the outstanding securities balance. Overcollateralization can be structured initially or built from excess spread over time.

- Initial overcollateralization is created by depositing collateral into the trust in excess of the par amount of securities to be issued.

- Overcollateralization can be built over time by “turboing” excess spread (i.e., using excess spread in addition to normal principal collections) to retire bond principal until target overcollateralization levels are achieved.

Overcollateralization is effectively invested in the collateral backing the transaction, and therefore avoids the negative carry associated with a reserve account.

Subordination

While reserve accounts and overcollateralization normally support the entirety of issued securities, it is also possible to have assets behind one or more classes of lower-rated securities provide credit support. Subordination of one or more classes is accomplished by defining the payment priority of the trust to favor certain classes over others in receipt of principal cash flows. Subordination requires no additional cash or receivables, but does have an effect on execution, since some securities receive lower ratings due to the lower likelihood of ultimate receipt of principal. Simpler structures may use only two levels of subordination—for example, a single-A class supporting a triple-A class or classes.

Motivation

Loan and lease originators require access to capital in order to engage in loan and lease production. Commercial banks and other institutions with significant balance sheet capacity and a low cost of financing, often choose to retain assets they originate and fund them with deposits or unsecured debt. Securitization presents an alternative source of asset financing. Independent finance companies typically do not have the balance sheet and ratings to finance receivables economically through unsecured debt. They sell loans into securitizations and retain a first loss piece (also known as securitization residual or securitization equity). There are multiple reasons for asset originators to securitize their assets. For many, the biggest benefit is a lower cost of funds. The bankruptcy remoteness of the SPE can, and often does, result in a credit rating for the ABS that is higher than that of the originator itself.

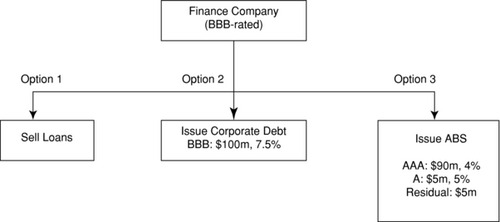

Exhibit 10.6 Simplified Funding Options

Let's consider the example presented in Exhibit 10.6. A finance company with a BBB rating has a pool of loans and needs additional funds to originate new loans. Broadly speaking, the finance company has three funding options:

1. Sell loans. The company could sell its existing portfolio of loans. A pool of assets may either be offered for competitive bidding or be sold to a specific buyer on prearranged terms as part of a larger arrangement. While this would generate cash, it does have several drawbacks. First, the originator would need to find a buyer for the loans who is looking for assets that match the specific duration and credit risk profile of the loans themselves. Let's say we are dealing with a $100 million pool of retail auto loans with a weighted average remaining term of 48 months, weighted average interest rate of 6 percent, weighted average FICO score of 690, significant share of used vehicles, and so on. In this case, the target investor pool would be constrained by a lack of credit rating and the fairly unique nature of the credit risk that this pool would present. Such uniqueness limits the number of possible investors and drives up the cost of capital, driving down the sale price. Furthermore, if the originator chooses to sell the receivables, the company forgoes any upside in the assets’ performance. If the assets perform better than expected, the originator does not benefit (the converse is also true—if they perform worse than expected, then there is no additional loss to the originator).

2. Issue corporate debt. The company could issue corporate debt. The issuer would retain any upside if the assets perform better than expected. The company would also retain any downside if the assets’ performance is worse than expected. The cost of funding the assets would be the marginal cost of funds to the company. For purposes of the example that follows, we will assume this cost to be 7.50 percent.

3. Issue ABS. By issuing ABS, the company could obtain financing with weighted average cost of 4.05 percent, which means savings of 3.45 percent relative to the cost of issuing corporate debt. Additionally, by retaining the equity or first loss piece, the company retains any upside from better than expected collateral performance. Similarly, if the assets perform worse than expected, the company's losses are capped at its retained exposure (5 percent of the collateral pool in our example).

In our example, issuing ABS is the superior financing option. In reaching this conclusion, we are comparing 7.5 percent cost of corporate debt with 4.05 percent weighted average cost of ABS debt (assuming pro rata amortization of all ABS tranches). While this comparison makes sense for $95 million of debt out of a $100 million loan pool, our conclusion fails to take into account the fact that the entire $100 million needs to be financed. Under the third option, the incremental $5 million is a highly levered piece that is likely to carry a high assumed cost of funds and would move the weighted average cost of funds above the level of 4.05 percent.

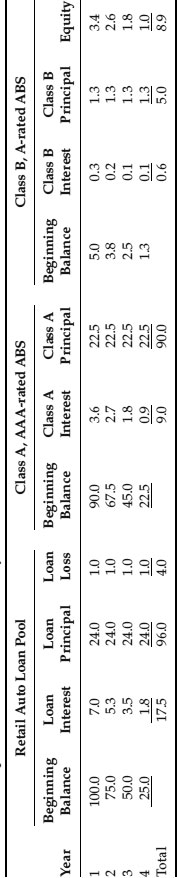

Cost of equity is often an important consideration in choosing between options 1 and 3. Let's assume that after marketing this pool of loans to a range of prospective buyers, the owner has ended up with the best level of $101 million for the $100 million pool of loans. The owner now needs to compare this execution with results under option 3. The owner knows that the pool can generate $95 million from the sale of ABS. However, putting $101 million side by side with $95 million is not a fair comparison since the owner would derive an incremental value from the ownership of the securitization residual under option 3. Thus, $95 million needs to be supplemented with the value of the residual. The value of a residual piece is typically computed as a present value of projected cash flows under a certain loan pool performance scenario. Exhibit 10.7 shows simplified collateral, bond, and residual cash flows for a $100 million retail auto loan pool. Total cash flow to the residual stands at $8.9 million. Assuming a 15 percent discount rate, net present value of the residual stands at $6.7 million. Combined with ABS cash proceeds of $95 million, the total pool value stands at $101.7 million and exceeds the market level of $101 million, pointing to option 3 for the owner of the pool. Let's change the discount rate assumption to 25 percent. In this case, net present value of the residual would drop to $5.75 million, leading to total transaction value of $100.75 million and pointing to option 1.

Exhibit 10.7 Simplified Sell versus Securitize Analysis

Needless to say, in real life these choices are driven by a variety of additional considerations such as accounting treatment, rating agency treatment, and transaction fees.

Securitization has multiple additional benefits. As discussed earlier, the ability to secure higher ratings on certain bonds than the issuer itself is rated can result in a lower cost of funds. This is particularly true for lower-rated issuers or collateral pools of higher-quality assets. As a general rule, the funding cost advantage declines as an issuer's rating improves and/or the asset quality declines. We highlight a few additional benefits of securitization:

- Diversification of funding. Securitization increases the range of financing options for an originator, particularly for lower-rated issuers that may have more limited access to the capital markets.

- Asset-liability management. Securitizing a pool of assets can help reduce or eliminate interest rate and duration mismatches on an originator's balance sheet.

- Risk management. By securitizing a pool of loans and retaining the residual or first loss piece, the issuer retains any upside from better than expected collateral performance. The potential losses are also limited to retained portions of the securitization.

TRANSACTION PROCESS

Loan originators hire investment banks to structure and sell securities. Debt underwriting is largely a fee business for investment banks. Banks may or may not provide firm commitments to sell bonds at certain spread levels, depending on circumstances. Typically, a group of banks is picked to do a transaction. Among many considerations, originators tend to choose based on indicative or guaranteed pricing, reputation, and strength of institutional relationship. Within a group of banks picked to execute a transaction there are lead managers who take a primary role and co-managers. Typically, one of the lead managers is in charge of structuring the deal.

As a first step, the structuring bank comes up with multiple structural alternatives and shares economics in each alternative with the client. Once the optimal structure is chosen, bankers work with rating agencies to get credit ratings and with lawyers to prepare necessary offering documents. Marketing and sale of bonds to investors conclude the transaction process. If necessary, the investment bank brings other parties into a deal. For instance, a deal may benefit from a derivative product (such as an interest rate swap or interest rate cap).

CREDIT RATINGS

Rating agencies evaluate deals and assign credit ratings based on estimated creditworthiness of individual securities. Although credit ratings are not intended as recommendations to buy or sell specific securities, on most occasions bond investors take ratings into account in their investment process. While some investors may find rating agency analysis helpful, others are simply required to take ratings into account due to the institutional role that ratings play. Over decades, credit ratings have made their way into investment guidelines, capital adequacy rules, and all sorts of regulations.

In assigning credit ratings, rating agencies study various aspects of a securitization. Rating analysts dedicate significant effort to studying the legal framework of any given deal with a goal of ensuring legal isolation of assets sold to an SPE and continuation of harvesting of such assets for the benefit of bondholders in case of bankruptcy of a seller of assets. On a quantitative front, rating agencies engage in extensive analysis of bond performance under a variety of collateral scenarios. Let's perform a simplified rating agency analysis using auto loan securitization as an example. As a first step, rating agencies would study the collateral pool and develop a view with regard to future collateral performance. Projected portfolio credit loss rates are a function of projected default rates and projected loss severity rates. Historically, auto loan default rates have been primarily driven by the state of the labor market. The main factors that drive auto loan loss severity are the economic environment, new vehicle incentives, used car supply from fleet leases, and general availability of credit, as well as credit terms. In analyzing collateral performance, rating agency analysts would also focus on a variety of factors, including historical performance of assets originated by the same entity, loan prepayment rate expectations, credit scores, geographic concentrations, loan seasoning, and so forth.

Then, using their knowledge of the collateral as a starting point, the agencies would come up with multiple collateral performance cases in order to assess the strength of a proposed capital structure. Fundamentally, there are two approaches to such analysis.

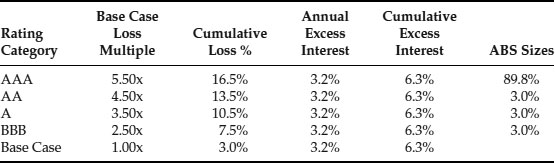

Under the first approach, which is known as deterministic, the rating analyst would come up with a small number of scenarios for each rating category and would evaluate bond performance under each scenario in order to make sure that each bond with a targeted rating X is able to pay full interest and repay full principal in stress scenarios associated with such rating. For example, let's assume an analyst has come up with the following base case and stress scenarios for the auto loan pool described earlier in the chapter. (See Exhibit 10.8.)

Exhibit 10.8 Simplified ABS Debt Sizing

Assuming a weighted average life of this collateral pool at two years and using a simplified back-of-the-envelope approach to debt sizing, the analysis will yield bond sizes shown in the last column on the right. Using an AAA-rated Class A bond as an example, the rating agency guideline requires that Class A be sized to survive a loss of 16.5 percent of the collateral pool. With excess spread covering losses of approximately 6.3 percent of the collateral pool, the rest needs to come from excess collateral (subordination and overcollateralization) and, as such, drives the sizing of Class A to 89.8 percent. In reality, detailed bond cash flow analysis is necessary to derive bond sizes in each rating scenario. Among many things, in a detailed cash flow run, higher loss rates and faster prepayment rates relative to the expected case will reduce the amount of excess spread. Therefore, since the yield on the assets itself is subject to curtailments due to defaults and prepayments, the rating agencies will give credit for only a fraction of the excess available as credit enhancement. In some cases, more credit will be given to the excess spread by the rating agencies if the excess spread is trapped in a reserve account or used early on to build overcollateralization by paying down principal on the securities.

The second analytical approach deals with a large number of simulated collateral performance scenarios. After setting base case assumptions for any given collateral pool, rating agency analysts would estimate statistical distributions for each variable. Using distribution parameters as inputs, rating agency models would produce thousands of performance scenarios and measure bond performance in each. Bond ratings are derived by comparing average bond performance with a benchmark performance set for a particular rating category.

Whether bond sizes are determined based on a small number of well-defined scenarios with a goal of achieving full timely payment of interest and principal, or based on a large number of simulated collateral scenarios with a targeted average performance for each security, the key challenge from a rating agency perspective remains in identifying input parameters for stress testing for different rating categories. The agencies run internal processes that require extensive collateral research followed by committee approvals of stress scenarios and collateral assumptions. It is not uncommon for different rating agencies to come out with dissimilar views on a particular deal, resulting in different credit ratings for the same bond.

Recent Events

Banks typically have large deposit bases and low cost of funds. However, they also prefer to lend to high-credit-quality borrowers. In contrast, much of the lending to medium- to lower-credit-quality borrowers is done by finance companies with smaller balance sheets. The ABS market allows these lenders to originate, securitize, and use the proceeds to fund new lending. The development of the “originate and sell” model, rather than the “originate and hold” model, has helped spur the growth of credit available to consumers and firms alike, as well as lowered the cost of that credit. Issuers also don't have to raise new debt, or wait for existing receivables to pay down if they want to grow their business. From the mid-1990s to 2007, this phenomenon led to the emergence of lenders that relied almost exclusively on securitization for funding their lending businesses. These lenders had very limited balance sheets of their own. Their loan origination policies and pricing were driven by ABS investor and rating agency requirements. By early 2007, investors had become concerned with exposure embedded in certain types of real estate–related securitizations. With investor appetite waning, many independent finance companies lost their primary funding source and were forced to shut down in the period from 2007 to 2009, leaving a significant segment of the population without access to borrowing and without ability to refinance existing loans. This led to increased consumer defaults, which in turn led to actual and expected deterioration in ABS collateral pools, leading to further loss of investor appetite and creating a vicious circle. Plunging bond prices crippled the balance sheets of even large financial institutions. This led to further widespread credit contraction that affected business confidence and undermined employment.

In early 2007, ABS issuance was running at a strong $70 billion to $80 billion per month. Approximately 65 to 75 percent of that total was subprime and ABS CDOs. As the residential credit crisis started to appear, investor appetite for subprime assets quickly evaporated and issuance rapidly declined. By August 2007, total subprime and ABS CDO issuance had fallen to less than $10 billion, and by the fall of that year it had fallen virtually to zero. By early 2008, ABS issuance had shrunk to just $10 billion to $15 billion a month and consumer ABS (autos, credit cards, and student loans) made up about 95 percent of the total.

In order to revive consumer lending, which had become increasingly dependent on ABS funding over the years, the Federal Reserve Bank and the U.S. Treasury introduced the Term Asset-Backed Lending Facility (TALF) in early 2009 with an aim to restart the new-issue ABS market. The TALF program allowed investors to borrow from the Federal Reserve against newly issued ABS debt, and the leverage provided significant returns to the investor, creating huge incentives for hedge funds and other nontraditional ABS investors to invest in new issues. Although the TALF program got off to a slow start due to initial confusion over the terms of the program, investors gradually got more comfortable, and by mid-2009 new issuance in the U.S. ABS markets had increased back to $10 billion to $15 billion a month, largely driven by auto loan and credit card securitizations.

By the end of 2009, the recovery in the ABS markets was fully underway with spreads on traditional ABS issuances (auto loans and credit cards) having come in dramatically tighter than the highs seen at the peak of the credit crisis, although still wider than pre-credit-crisis levels.

Fundamental collateral credit concerns were at the core of the investor panic in 2008. However, aside from credit considerations, there are other potential issues that affect ABS valuations, bond performance, and issuer risks.

Credit versus Liquidity: The Student Loan Example

The Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP) student loan ABS provides an excellent example of the importance of liquidity in credit spreads. Both principal and accrued interest (from 95 percent to 100 percent, depending on the year of origination) on FFELP student loans are guaranteed by the U.S. government. In fact, unlike agency debentures, the guarantee is explicit, not implied. One might have thought FFELP student loan ABS would benefit from the general flight to quality that took place during the credit crisis. In fact, the opposite occurred as spreads on FFELP student loan ABS widened to unprecedented levels in 2008. Investors chose to flee into liquid U.S. Treasury securities, seeing ABS spreads as an insufficient premium for lower liquidity.

Breaching Triggers

Triggers could cut off cash flow to subordinate bondholders and the residual holder. Triggers are a credit enhancement mechanism and are often used to redirect cash flow away from subordinate tranches to senior tranches in the event that collateral performance is worse than expected. Breaching a collateral trigger can have two effects on subordinate bondholders. The first is an extension of the bond's weighted average life. If principal payments on a subordinate bond are redirected to pay down the senior classes, the bond will extend. Investors who thought they had purchased a bond with a certain duration will find themselves holding a bond with a potentially much longer duration. The extension may also cause the loss profile of the bond to increase. For example, if a bond is paying pro rata with a senior bond and a trigger is breached that causes the waterfall to switch to sequential, then principal payments will cease, exposing the bondholders to a greater potential write-down.

Triggers can also be problematic for the issuer. Many issuers retain the residual pieces to their securitizations. To the extent that they are relying on ABS residual cash flows to provide working capital to the company or to originate new loans, a breach of a trigger that cuts off residual cash flows could lead to liquidity problems. This problem becomes even more acute if the issuer's transactions are cross-collateralized. When trusts are cross-collateralized, a breach of a trigger in one trust may cause all cross-collateralized trusts to redirect cash flows. Cross-collateralization typically leads to lower subordination levels, lowering the issuer's cost of capital, but doing so at the expense of increased exposure to deteriorating collateral.

Duration Mismatch

Another issue that has emerged is funding long-term assets with short-term liabilities. The turmoil in the auction-rate securities market is a good example of this. Many student loan originators issued auction-rate securities tranches in some of their ABS trusts. The use of auction-rate securities in student loan ABS was most common among municipal agency issuers, although most major issuers, including the Student Loan Marketing Association (SLMA, Sallie Mae), the National Education Loan Network (Nelnet), and First Marblehead, all issued auction-rate securities in certain deals. Auction-rate notes are often issued in 7-day, 14-day, and 28-day periods. At the end of each period, a Dutch auction is held to determine the rate for the next period. If new investors cannot be found, then the auction is said to have failed and existing note holders retain their securities, usually with a step-up in the coupon. In March 2008, as the credit crisis froze much of the capital markets, auctions failed at record levels, leaving many auction-rate security holders stuck at their maximum rates with what they assumed were short-dated securities. Unless issuers choose to refinance these securities (at higher costs), many auction-rate investors will be holding these securities for a substantial period of time. Given the spreads these securities traded at, it is clear that investors and issuers had not properly priced the option component of these securities.

![]()

Although the ABS markets have revived again, there are some fundamental changes that have taken place as fallout from the credit crisis and the resulting buyer's market:

- Rating agencies, which were seen as primary contributors to the subprime fallout due to their flawed methodologies for providing AAA ratings to highly leveraged subprime ABS and CDO offerings, have become more conservative in their ratings process and have raised the requirements for issuers to obtain the highest ratings on their ABS issuances.

- Investors are now demanding more information disclosure on underlying assets from ABS issuers and are spending more time performing their own credit analysis with lesser reliance on credit ratings obtained by the issuers. More frequently, for nontraditional assets, transactions are being initiated on the basis of reverse inquiries from investors, or being executed as private placements with a small group of investors who negotiate not only the terms at which they would buy the debt, but also some of the key structural features they would require in the transaction.

- The absence of monoline insurers from the ABS markets has made it more expensive for many issuers to fund their assets through securitization, as the bonds now have to be rated based on actual credit enhancement in the transaction; this holds true especially for securitizations backed by operating assets such as rental car/truck fleets, aircraft and container leases, and restaurant franchise royalties, among others, which historically have been structured and sold largely with external credit enhancement provided by the monoline insurers.

- Regulators continue to work on a wide range of new and revised rules, including capital adequacy rules, which may significantly affect attractiveness of securitization in the future.

- It remains to be seen if these changes are a temporary response due to the supply/demand imbalance in the credit markets, and if the ways of the market will return to the pre–credit crisis days as regulations settle down, deleveraging stops, and as the demand for credit and the risk appetite increase.

Note

1. Data provided by CNBC and Thomson Reuters.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Konstantin Braun is a managing partner at Smart Energy Capital, a finance and investment company focused on the North American solar photovoltaic industry. He has 15 years of structured finance and financial engineering experience; he structured, rated, and marketed over $100 billion of transactions, including securitizations for Citibank, Sallie Mae, Ford, Public Service Electric and Gas (PSE&G), Dunkin’ Donuts, International Lease Finance Corporation (ILFC), Hertz, Crown Castle, and many others. Formerly a managing director at Lehman Brothers, most recently head of ABS/MBS structuring, he provided debt structuring expertise in connection with the origination and execution of asset-backed securities collateralized by a wide range of asset types; in addition, he provided loan pricing and funding for Lehman's proprietary, nonmortgage consumer finance origination and securitization platforms. Konstantin holds an MA in international economics from Yale University and a BS in economics/mathematics from Moscow University.