Chapter 2

Careers in Financial Engineering

INTRODUCTION

The evolution and growth of financial engineering as a profession has been accompanied by an ever-increasing demand for qualified job candidates. The field is interdisciplinary and had existed under a number of different, sometimes inappropriate, labels for some time before industry and academia finally settled on the more accurate descriptor of “financial engineer.” The roots of financial engineering trace back to major theoretical contributions made by financial economists during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. They include names like Harry Markowitz, Merton Miller, Franco Modigliani, Eugene Fama, William Sharpe, Myron Scholes, Fischer Black, Robert Merton, Mark Rubinstein, John Cox, Stephen Ross, and many others that walked with them or followed the trail they pioneered. These men brought a new set of tools and a more scientific approach to finance to our understanding of financial markets, financial products, and financial relationships. However, as important as these contributions were in planting the seeds for a new profession, the blossoming of that profession did not occur until the financial markets began to experience an influx of highly skilled professionals from other, traditionally more quantitative, disciplines. These new entrants to the financial markets included ever more physicists, mathematicians, statisticians, astrophysicists, various types of engineers, and others who shared a love for quantitative rigor. Some of these people came to finance because they reached a point in their lives when they simply wanted to do something different. Others came because they were displaced by a changing world.

As the years passed, the initially fragmented discipline began to coalesce into an increasingly recognized and respected profession with its own professional organizations and recognized leaders. As the field evolved, it attracted some of the most respected minds from academia, both in traditional finance programs at respected business schools but also at leading engineering schools. Many of these people were drawn to financial engineering by the nascent markets for derivatives and later by the advent of securitization. While the opportunities and the variety of employment roles that are available to prospective financial engineers have increased dramatically over the years, the popular press all too often names the people engaged in the profession as “quants” (short for quantitative analyst). Nevertheless, not all financial engineering careers require an advanced study of mathematics. While many do, and some quantitative training certainly does help, there are many niches to be filled in which mathematics plays a less important role.

There are, today, a wealth of career opportunities available to competent financial engineers. As the field, first defined and given a name only about twenty years ago, has grown, over 150 universities and colleges have introduced courses and/or degree and certificate programs devoted to dimensions of financial engineering.1 In this chapter, we present a framework to examine the range of career opportunities available.

In the most recent survey of financial engineering graduates, performed by the International Association of Financial Engineers (IAFE), career objectives showed a remarkable homogeneity. Of all the students surveyed, 56 percent of graduates wanted to work in a field related to derivatives pricing or trading, with a further 21 percent pursuing opportunities within risk management. This survey was performed in advance of the credit crisis. What is most surprising is that—with the extensive variety of opportunities available—over three-quarters of graduates were interested in such a concentrated group of fields. With over 5,000 financial engineering students now graduating annually,2 it is important to more fully appreciate the wide set of opportunities outside of derivatives.

At first glance, it is understandable why students are drawn towards derivatives. Derivatives have become the archetype of financially engineered securities. They can be found in almost every market sector. But derivatives are far from the only area in which financial engineers are needed. The growth of automated trading strategies, for example, is but one of the many new opportunities in the markets where financial engineers are much in demand, as was securitization before that. With the massive spread of complex securities, opportunities and challenges abound in managing the risks faced by firms. With an estimated 750,0003 risk practitioners across all industries, risk management remains one of the largest areas in which financial engineers can build a career.

The purpose of this chapter is to give the reader a sense of the breadth of financial engineering careers and to make it a bit easier to understand what skill sets are sought when the student reads job-posting notices. For example, within the realm of job postings titled “Quantitative Analyst,” there is great variety in the types of analysis to be performed and in the nature of the employers. Quantitative analysts, and therefore financial engineers, are not simply in demand for roles on the CDO structuring desk within global banks. Rather, they are in demand across a broad spectrum of firms and in a large number of roles. The requirement and demand for quantitative analytical skills bridges across from banks, financial services firms and insurance companies to corporations, service companies, governments, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The skills developed during a financial engineering program are understood to apply far beyond the technical scope of financial instruments. Employers seek the strong analytical skills instilled during the student's program of study. These characteristics are also why the profession continues to draw people from other analytical backgrounds, applying their skills to financial problems.

The job functions of individual financial engineers can vary dramatically despite similar job titles, firms, and even business divisions. This will become noticeable if the reader reviews the details in a number of similar-sounding job postings. The similarities will generally be immediately apparent, but there will also be many subtle differences. A prospective candidate should be able to quickly identify the variety of businesses that employ financial engineers. Yet, beneath this, there are numerous roles that include programming, financial modeling, and data analysis. For some new entrants to the industry this can be challenging. To assist you, we have attempted to present the roles available by highlighting key components. Our hope is that, by doing this, you will be able to use this chapter in conjunction with job descriptions to better understand the nature of the role advertised.

At the conclusion of this chapter the reader will find tables that present a summary of the types of roles and opportunities available to a financial engineering graduate. When we first sat down to write this chapter, we were tempted to simply populate the tables with the role “Quantitative Analyst.” This would have served to make the point of how widespread quantitative analytical roles have become—originally, of course, in the securities and derivatives markets, but later spreading to such things as analyzing data trends for superstore purchases, marketing analysis, and even journalism. While we have tried to illustrate the range of employment opportunities that require financial engineering skills, the areas we have identified below should not be considered exhaustive by any means. The range of employment opportunities will continue to evolve—along with financial engineering as a profession.

A WORLD OF OPPORTUNITIES

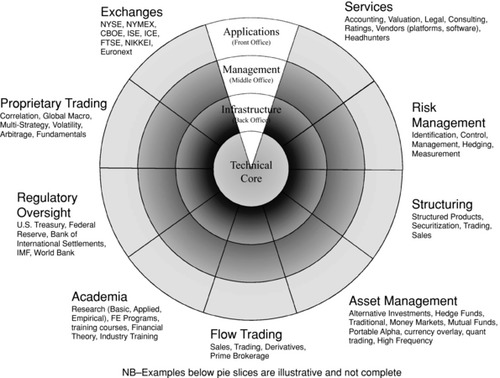

It is a challenge to illustrate the opportunities available to job candidates who have qualified themselves in financial engineering, whether through a formal course of study or through sufficient applicable experience. To assist the reader in understanding the variety of career paths available, we have developed the diagram in Exhibit 2.1. We envision a series of concentric circles, each of which depicts a functional area within a business or governmental entity. Think of these functional areas as the ingredients necessary to bake a pie. The “pie” is then sliced up into nine industry sectors that employ financial engineers and/or where quantitative analysts are sought. Some areas, such as “Services,” are defined very broadly and encompass a great many roles and business types. The objective of the image is to highlight the range of fields available to financial engineers and quants, digesting the multitude of possible career paths into an approachable framework.

Exhibit 2.1 Career Wheel for Financial Engineers

The concentric circles, which can also be thought of as representing levels of core competencies, illustrate the variety of functions within each of the sectors. In certain sectors, the differences in the job roles across the levels will be significant; in others, the differences will be minimal. Differentiating between the two is important if the job candidate is to identify the opportunities for which he or she is best suited.

The range of opportunities can be identified in part by reviewing the scale of offerings available within each sector. Risk Management, as highlighted earlier, is a sector in which over 750,000 professionals are estimated to be employed. Within academia, there are already 150 programs that are called, or offer substantial coursework in, financial engineering. Each employs a number of professors. Additionally, an even greater number of academics are employed within university finance departments at business schools that do not have a formal financial engineering program. For Asset Management, on top of all the pure asset management firms, a search identified 244 insurance companies in the United States alone that each employed more than 1,000 people and had annual revenues of USD 100 million.4 In surveys of the Hedge Fund industry, over 18,000 hedge funds and 7,050 fund-of-funds were identified, collectively managing approximately USD 1.4 trillion.5 In Regulatory Oversight, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) recognizes 166 central banks on its website, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Within each central bank there are likely to range from tens to hundreds of employment opportunities for financial engineers.

FUNCTIONAL AREAS

Technical Core

The technical core section for any career path encompasses the theories and principles that are the foundation for the field. The technical core underpins the field, providing idea growth and advancement in the field, both in academia and industry. It is unusual in that it need not be embedded within the business itself, often operating in areas that provide advisory solutions or thought leadership. This occurs within firms, but also within academia and specialized research firms.

The technical core will often center around research and development; developing and testing new theories and product possibilities that can, in time, be developed into an active business line. Most cutting edge firms require a continuous flow of fresh ideas. This often means that there will be a direct link to both established and emerging leaders in the academic community and a regular need to review work published in research outlets. Within risk management and asset management, for example, the role will involve extensive work in identifying new methods of creating and managing risk exposures for the business or for its clients. These roles require that the financial engineer keep himself or herself at the forefront of developments as they pertain to the business, either through incorporating academic research or actively engaging in research on their own.

Roles within the technical core may be captured under titles such as theoretical model review, product design, new applications, business strategy or business development. Roles also include lecturers and professors. The titles should not conceal the potential for extensive quantitative and theoretical analysis within these roles. Technical core roles will necessitate a more empirical analysis, analyzing the fundamentals and the principles that exist within each market space. Application of developments made in the technical core ultimately lead to new products and markets. The technical core is the area where financial engineers are most likely to need to apply computer programming skills (or work with those who do so).

Infrastructure

Underlying every successful business is a strong business architecture or infrastructure upon which all other areas can confidently rely. The business infrastructure is often referred to in a trading environment as the back office, a reflection of best-practice business segmentation. Today, the back office increasingly sits at the table with, and is compensated equally to, the front office for critical positions. The business infrastructure is the backbone that provides assurance within a successful operation. The infrastructure area within most financial institutions is responsible for the processing and verification of all activity with external parties—be this through brokers, exchanges, dark pools, Treasury auctions, over-the-counter transactions, or any other vehicle of exchange. The challenge for those working in business infrastructure is to provide assurance that all risk positions held by the firm are those into which it intended to enter, and all those that were not intended are resolved as quickly as possible.

The infrastructure role provides an important checkpoint within the business. It acts as an area of day-to-day operations and quality control, ensuring that all data and information are accurate within databases or models or transactions. With the increase in compliance-related reporting necessitated by Sarbanes-Oxley, the demand for financial engineers has increased dramatically within infrastructure departments. The function requires specialized skills in the stratification of data, so that information can be processed accurately without demanding excessive resources or time. Infrastructure departments also employ advanced data mining techniques to identify data mismatches and any inconsistencies that can reflect fraudulent activity within the business conducted.

Management

Acting as the interface between applications and infrastructure, the management area within the middle office holds responsibility for the oversight of activity, aggregation, and verification of business practices. The management function is most commonly identified as the center of risk management and control within the enterprise. With the evolution of more complex business strategies and financial products, the management function faces an ever-increasing challenge in the comprehension of risks within the business, and also the communication of these risks to both the front office and executive offices. The complexity and challenge within the area provides two main avenues of opportunity for financial engineers.

First, financial engineers have numerous opportunities available in the area of reporting. Moving from raw business data to a risk report creates a requirement for extensive data synthesis, computer programming, and mathematical manipulation. As executives seek reporting with greater immediacy and increasing accuracy, financial engineers must deliver on these requirements.

Second, management areas need to consistently work to identify or create new metrics to highlight the risks embedded within products and the risks held within the business. Researching and identifying new metrics and approaches within the management function can often lead to a role in the applications area; new risk perspectives and approaches can redefine the business approach, developing new products or strategies by identifying risk categories. By working to better understand and communicate the risks the business has, management can better position the firm to decide which risks it should keep and which risks it should not take (at least in the present).

Applications

The applications area, alternatively known as the front office, is the area where products often are designed, priced, and ownership is transferred. Acting as the interface between the firm and its customers, this area depends heavily on its technology and requires a solid infrastructure that can expeditiously and accurately price products and provide information on positions.

The front office will be, in part, serviced by software and reporting that is compatible with that provided by risk management and the technical core. The primary function for financial engineers within applications is in the development of tools to best assist the firm in assuming new risks. These models will combine elements from inventory, risk mitigation prospects, and market information to best comprehend the price that the market can bear, and also the price at which it is economically acceptable for the firm to assume the risk. Front-line applications are critical for ensuring that new transactions are entered into without the firm either losing money or assuming risk without adequate compensation.

The nature of the applications area differs across different types of businesses. It can involve working as the lead author in drafting articles on financial markets and events, leading relationship teams for regulators, or implementing software solutions for clients. All of these roles require the ability to configure products to best suit customer needs, to quickly adapt to a changing environment, and to complete tasks to a high standard.

SPECIFIC CAREER PATHS

From the illustration in the previous section, it should be apparent that there are many more career paths for financial engineers than one might initial think. Further, within the functional areas of applications, management, and infrastructure, multiple roles exist in each of the different sectors mentioned in the preceding section.

The reader will notice that we have altered the specific careers discussion below a bit from the diagram that we laid out above. This was done to highlight the variety of roles included within the Regulatory Oversight and Services sectors of the diagram. These are expanded a bit below to better identify different opportunities with software firms, service companies, consultants, and ratings agencies, covering a diverse grouping of roles within the Services sector.

Sell Side

The term “sell side” refers, primarily, to the global bank and broker-dealer community where the principal business is “selling” financial instruments and research. The term “selling” actually includes both the buying and the selling of financial instruments in the capacity of dealers, which, of course, requires that they provide both a bid and an offer. Nevertheless, “sell side” is well understood to refer to the global bank and broker-dealer community. Sell side firms make both the primary and the secondary markets for securities. The former involves the initial sale of a security by an issuer. This could take the form of stock being sold in an initial public offering (IPO) or an established public company selling additional stock in a seasoned public offering (commonly called a follow-on offering). Primary market offerings of debt securities include the underwriting of bonds, the private placement of structured securities, and the syndication of loans. The secondary market involves all transactions in a security following the initial sale of the security—that is from investor-to-investor rather than issuer-to-investor. Sell-side firms participate in the secondary markets in two distinct but related ways: They broker transactions in exchange for fees called commissions, and they make markets by acting as dealers. For many, market making is the essence of their business and rewards them through the bid-ask spread associated with the financial instruments they trade.

Sell-side firms seek to handle as large a volume of transactions as possible while holding the minimum inventory sufficient to function efficiently. They leverage their distribution networks to buy side firms, and through institutional and retail brokerage units. Historically, these services were rendered by the firm's trading floor personnel. Increasingly, however, much of this activity has moved over to specialized prime brokerage units that have grown extensively over the past few decades.

With the revocation of Glass-Steagall in the United States, a number of traditional sell-side firms began to add components traditionally associated with the buy side (e.g., insurance, and asset management). The recent Dodd-Frank legislation is expected to reduce the scale of this overlap going forward. Here we consider firms whose principal activity is to provide sell-side functionality to clients, irrespective of their proprietary trading activities.

Examples of sell-side firms include investment banks, commercial banks, broker-dealers, and global banks.

Buy Side

The buy side is typified by firms that are entering the financial markets to implement an investment strategy. In some ways, it is the inverse of the sell side, where the objective is to minimize inventory and facilitate transfer; a buy-side firm seeks to accumulate a specific inventory through market transfer.

Whereas the sell side format is relatively homogenous, buy-side firms are highly varied in their objectives, strategies, and scale. Buy-side firms include the traditional types, such as insurance companies, pension funds, endowment funds, mutual funds, and unit trusts, but they also include some non-traditional types, such as hedge funds and private equity funds. The non-traditional types are often called alternative investments, and they differ from more traditional buy-side firms in several important ways. These include manpower, infrastructure, regulation, and the investment approaches they employ (we treat alternative investments separately later). The holding period of an investment position by buy-side firms can vary from several years (e.g., pension funds) to much shorter terms. The number of invested positions held can vary from just a handful to hundreds. Also the risk appetite and investment instruments available to the firm can vary greatly, with differing levels of proprietary trading decision making permissible.

Examples of buy-side firms include fund managers, exchange-traded funds, pension funds, insurance companies, mutual funds, and investment manager.

Alternative Investments

In the context in which it is applied here, “alternative investments” captures the firms within the buy-side space that require their investors to satisfy, at a minimum, the accredited investor condition under the Securities and Exchange Commission's Regulation D. Alternative investment firms will typically aim to outperform a benchmark index, similar to the objective of other buy-side firms. The difference is that these firms are prepared to take on more risk and employ higher degrees of leverage in their strategies to achieve their return objectives.

Many alternative investment firms employ strategies that carry a reduced level of diversification and, in some cases, deliberately take on concentrated exposures. These vary from high-speed, low-latency trading strategies that employ artificial intelligence programming and that hold positions for, at most, months, to global macroeconomic strategies and private equity where positions are often held for years or even decades.

A key difference to job applicants between alternative investment buy-side firms and traditional buy-side firms is most often one of scale. While these firms may have significant amounts of funds under management, they will typically operate in a very lean manner with considerable overlap among job roles. Also, they occupy a space that, at present, operates in a much different regulatory environment to that of pension funds, insurance firms, and mutual funds.

Examples of alternative investment firms include hedge funds, fund of funds, private equity, and alternative asset managers.

Central Banks

Central banks operate as important governmental participants within the markets. They are principally involved in managing the money stock, liquidity, the cost of credit and foreign exchange. They actively participate through open market operations in the purchase and sale of sovereign debt, and they intervene when they feel it necessary in the foreign exchange markets. Though less common, they may also participate in the commodities markets and the non-governmental debt markets when necessary (for example, the Troubled Asset Relief Program). Consequently, the central banks require the same expertise and knowledge required of all active private sector market participants.

Regulators

Most countries separate the regulatory oversight function of the markets and market participants from the functions of their central banks. Often this involves multiple regulators, each dedicated to oversight by product, sector, or function. For example, securities markets may be overseen by one regulator while commodities markets are overseen by a different regulator. Banks may be overseen by several different regulators depending on the purpose of the regulation. Insurance companies, too, often have their own specialized regulators. In order for a regulator to properly analyze the activity within the market where they have oversight responsibility, regulators require experienced participants and strong analytical departments.

Rating Agencies

The rating agencies perform the valuable service of opining on the credit worthiness of various institutions, sovereign states, and individual securities. The assessment of credit worthiness involves a detailed analysis of legal structures, credit hierarchy, accounting, and supporting assets. The ratings of rating agencies are an important component of many institutions’ investing rules, which, oftentimes, only allow investment in assets of a certain credit grade. The credit assessment also plays a major role in the pricing of debt facilities (i.e., bonds, loans, revolving lines of credit, etc.).

Three firms—Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch—have dominated the market. There are, however, numerous other ratings agencies, some limiting themselves to specific asset classes. These include Kroll, Dun & Bradstreet, Egan-Jones, Dominion, and Baycorp Advantage.

Service Providers

Service providers capture the array of auxiliary businesses that have developed around financial firms, typically operating to provide information services or prepackaged solutions and tools. The most ubiquitous and generalized firm within this space is Bloomberg LLP. Bloomberg not only provides real-time or delayed market data to licensed users, but has expanded to provide extensive analytical tools, including pricing tools, and other trading services. Many of the simple-to-use functions available to subscribers actually embody extensive financial modeling—but this is transparent to the user. For example, the system allows users to select from a variety of pre-engineered yield curves. And users can interact with the system to create their own curves using customized splines and other techniques. Behind the user-friendly front end lies sophisticated programming, financial engineering, and product development that has to adapt to ever-changing market dynamics.

There are multiple businesses that operate within niche spaces, providing custom data solutions for credit derivatives (e.g., MarkIt), financial statement analysis (e.g., Capital IQ), or some that compete across multiple fields (e.g., Reuters Thompson). In addition to acting as conduits for data flowing from the markets, these firms play significant roles in data synthesis, analysis, and modeling prior to delivering the data to clients. These activities require large numbers of highly competent technical specialists.

Custom Solutions

Custom solutions captures the over-the-counter market, where customized exposures are created for clients. The most publicly-visible structured products in recent years have been collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), a product involving extensive tailoring and orchestration to bring to market. Custom solutions can work with clients to create a bespoke exposure to meet their requirements—ranging from equity derivatives and commodities hedging tools to tax and funding solutions. The process for customizing solutions can be time consuming and is not comparable to the frenetic pace often seen on trading floors where standardized products trade. A customized solution often goes through numerous iterations and adjustments before it precisely meets the requirements of the client, obtains ratings agency acceptance, and achieves appropriate risk management comfort levels. Only after these things have been accomplished can custom solutions move forward and initiate the structure.

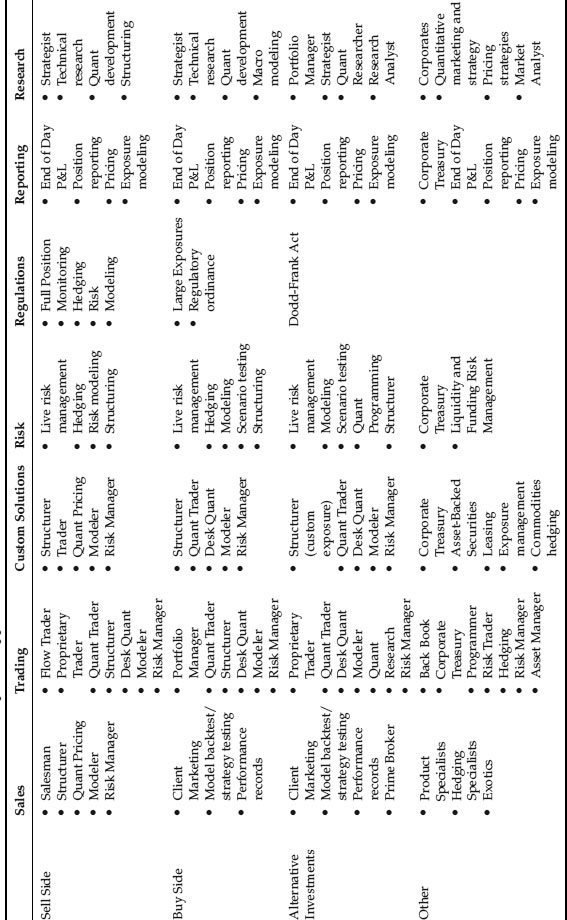

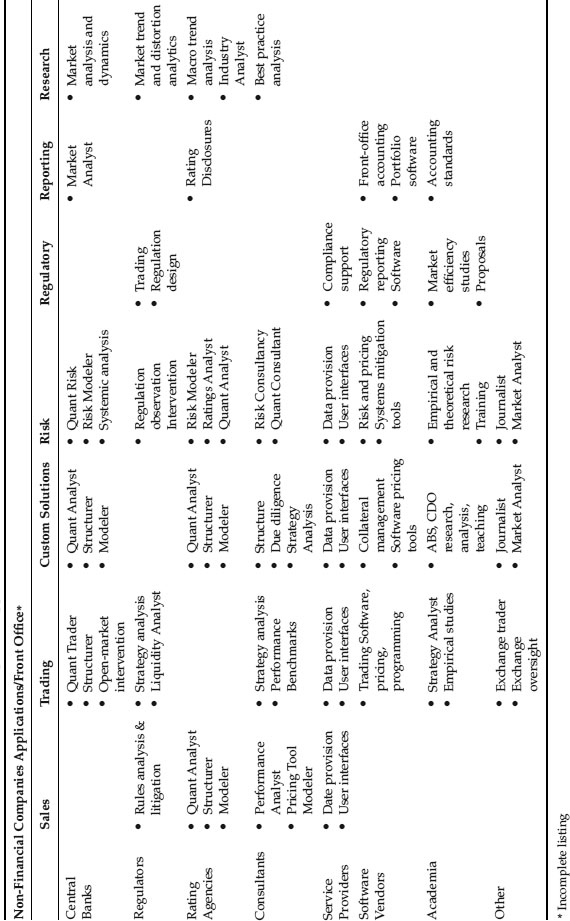

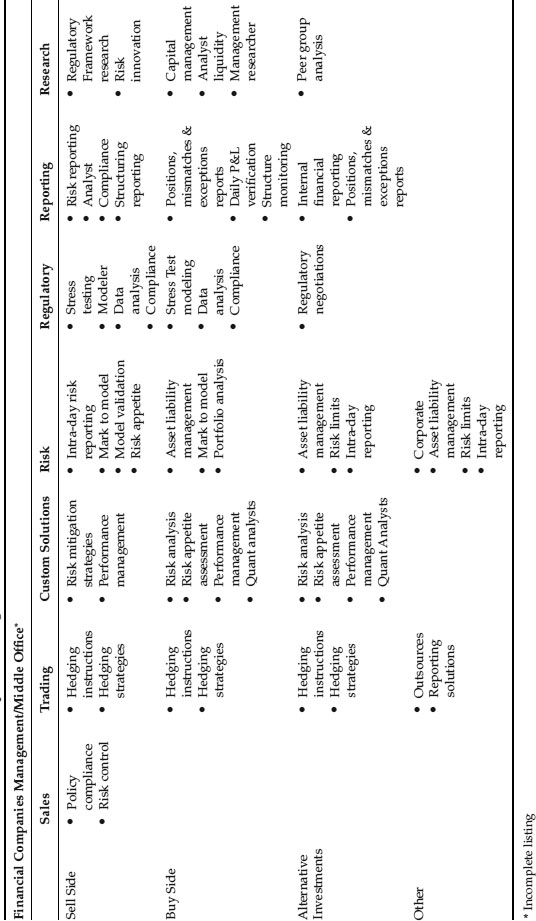

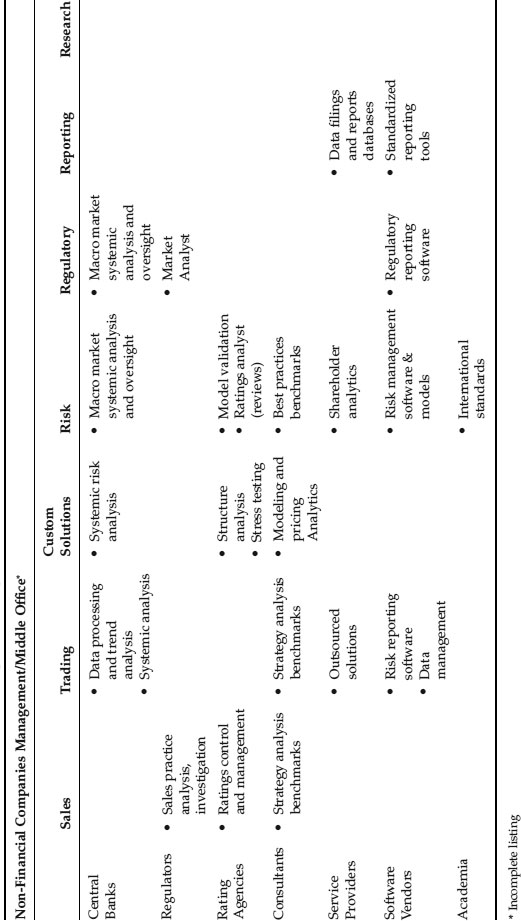

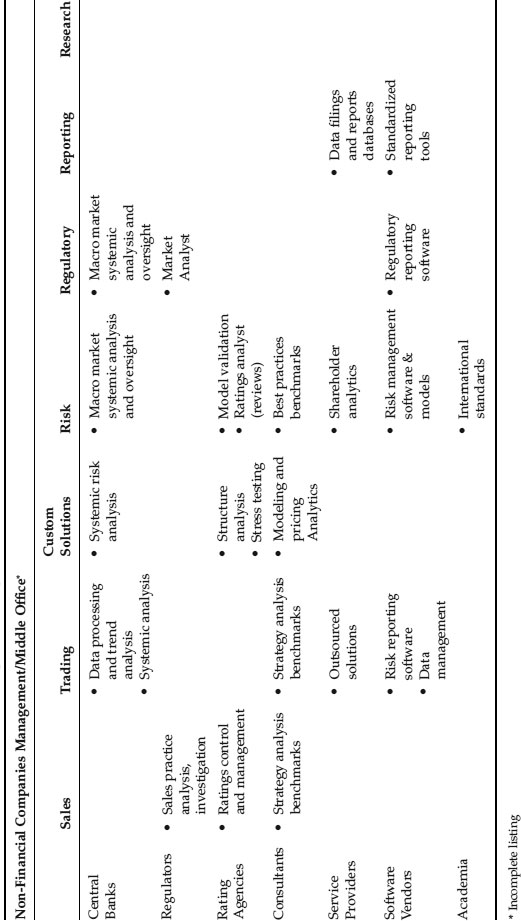

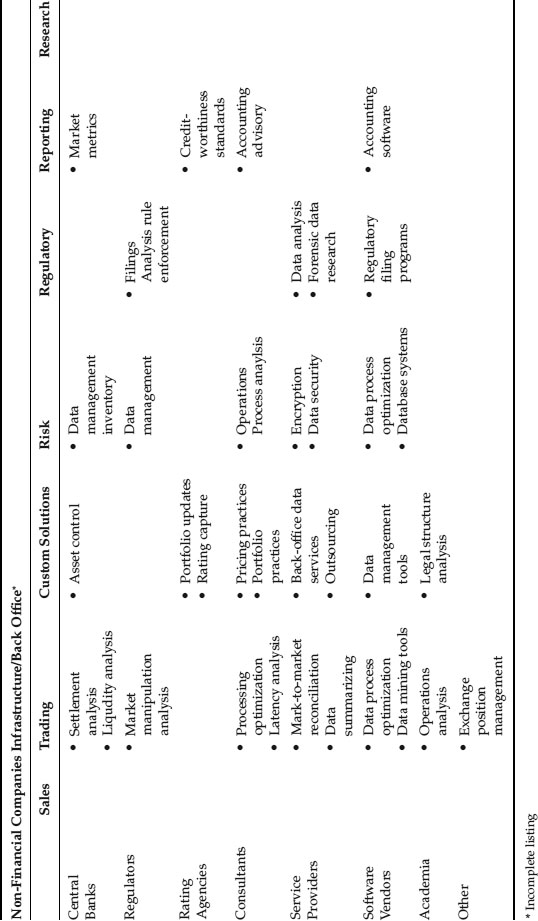

USING THE TABLES

Exhibits 2.2 through 2.7, contain a series of tables that illustrate the many roles for financial engineers and quantitative analysts. To illustrate to the reader how to read the tables, we will run through a few examples of the roles depicted in the table. We will explain why the same role appears in different boxes, and also how that role or job title may differ from one box to another.

Exhibit 2.2 Roles in Financial Companies: Applications/Front Office

Exhibit 2.3 Roles in Non-Financial Companies: Applications/Front Office

Exhibit 2.4 Roles in Financial Companies: Management/Middle Office

Exhibit 2.5 Roles in Non-Financial Companies: Management/Middle Office

Exhibit 2.6 Roles in Financial Companies: Infrastructure/Back Office

Exhibit 2.7 Roles in Non-Financial Companies: Infrastructure/Back Office

“Structurer”

Roles within structuring have been among the most coveted positions for financial engineering graduates over the last decade. The area has experienced extensive innovation and growth during this time period, leading to considerable diversity in the forms of structuring positions available.

The most common interpretation of a structurer would be the role played by an individual specializing in customized solutions in the front office of a sell-side firm. This is the area that is involved in creating the financial structure for the client and the active management of the resultant security. The structurer is involved in the selection of assets, working in conjunction with the client, rating agencies, and lawyers in building a structure that meets the objectives of the transaction.

There are several different structurer positions within sell-side firms, however. Both sales and trading require specialists within structuring to provide expertise to the market. Sales structurers operate within both the primary market, selling various tranches of structures created by custom solutions, and also within the secondary market to facilitate effective trading of existing holdings. Trading structurers need to be able to assess securities available in the market, provide valuation services, and be able to assess how the structure can be hedged. Trading roles will depend upon candidates being able to create bespoke models to aid price discovery within the marketplace. Within sales and trading roles, the emphasis of the structurer is on the analysis of a large assortment of structures; whereas the customs solutions structurer will work with a lower volume of securities, tailoring the product through numerous iterations.

Risk management also requires expertise in structuring, such that they can accurately manage and report the risks associated with structured securities, both prior to distribution and while the securities are held on the bank's balance sheet. Risk management and modeling will interact with the trading desk, potentially sharing components that feed into the tools for pricing securities. Research and strategy similarly require structuring expertise to produce market commentary and to make recommendations to clients and (or) to traders. Researchers will take an active role in analyzing securities, with strategists working on more macro-economic analysis of the marketplace.

Similar structuring roles exist on the buy side. Buy-side firms interact with structured securities to create exposure to markets they would not be able to access and also, rather famously, by providing insurance wrappers to senior tranches on structured securities. Subsequently, the buy-side firms need structurers to identify opportunities where they can create beneficial structures. Buy-side structurers need equally strong, if not stronger, skills in structured securities because the buy-side firm has the objective of keeping the exposure created, rather than selling it. Buy-side firms require structurers who can work with the sell side's trading and customized solutions personnel, but also with their own risk management departments, who must opine on the risks associated with the final product.

Alternative investment firms also employ structurers in a buying capacity. A notable example of this that attracted considerable regulatory scrutiny and press coverage was the involvement of Paulson & Co. Inc. (representing the buy side) in the design of the Abacus structure with Goldman Sachs (the sell side). As is common within alternative investments firms, there will be significant overlap between roles as the firm has a much smaller headcount. The role of a structurer will overlap with research and, potentially, risk management as the firm seeks to tailor an investment that reflects its market views. Risk management will be involved in the active mitigation of exposures that the firm does not wish to bear. Alternative investments firms are often active in very specific markets, with growth seen in the distressed structured credit market in recent years.

Structuring specialists are also required in the industrial sector, as some large firms use structured securities to manage their risks. Beyond the use of interest rate swaps and foreign exchange hedging tools, corporations have been active in the hedging of commodities within their product lines and cost structures. Structuring specialists within firms are able to work with their sell-side counterparts in creating the securities to mitigate risks, much as structurers on the buy side work to create risk.

The final group of market participants to require structuring specialists is the central banks. With the actions taken during the credit crisis, central banks now find themselves with large structured asset portfolios. They have moved to supplement their structurers engaged in systemic analysis of the products with structurers focused on trading, portfolio management, and risk management. Going forward, central banks will undoubtedly perform extensive monitoring of the marketplace, working alongside regulators to ensure systemic risks are minimized.

Opportunities outside of financial firms (applying the Dodd-Frank interpretation) for structuring specialists do not necessarily imply the role has less market involvement. Ratings agencies, while not actively participating within the market, require extensive structuring skill to model, assess, and evaluate individual structures before they are brought to market. The work performed at the ratings agencies mirrors the pricing, risk, and research functions within a sell-side bank, though they are employed to render an objective credit evaluation of the products.

Service providers and software developers also require structured products modeling specialists. Here the demand is for the technical expertise and understanding of the intricacies within structured products, in order to develop resources that will benefit market participants. These companies focus on providing tools that assist in analyzing, pricing, and quantifying the risks associated with these securities, so their role is not dissimilar to that of the structurers who support trading on the sell side or buy side. Consultants specializing in structured products will also provide modeling expertise and risk management alongside asset management strategies and—in some cases—the outsourcing of the management of a portfolio of structured securities. The consultant's ability to interact across all aspects of structured products is relatively unique in the spectrum of roles.

Structuring specialists are also found in other business lines that require a deep understanding of structured products. Within accounting and reporting, specialists with an understanding of structured products are needed due to the specific treatment required by each structure. Risk management needs to monitor the structures, identifying risk indicators and methodologies for portfolios of securities. Lawyers employ structured product specialists due to the non-standard legal documentation required by each new issuance. People familiar with the structures need to work to price the securities daily prior to their sale (as opposed to pricing for trading), either working from market prices of traded products or by building appropriate, often complex, valuation models.

What should be apparent here is that there are many job functions at different types of firms that have a need for a similar set of skills. Indeed, the need is far greater than one might expect. Further, due to the complexity of structured products, all of the roles require extensive knowledge of the product and typically have demands for financial modeling and programming to work with the scale of the assets.

“Quantitative Trader”

Our review of the possible employment opportunities for those financial engineers interested in structuring illustrated the varied nature of the types of firms that require this talent. While the type of work was similar in all cases, the types of firms hiring people with structuring expertise and their reasons for requiring the skill set are quite different. An examination of opportunities for quant traders, on the other hand, illustrates just how varied the type of work can be despite the similarity of job descriptions. With the Dodd-Frank reform, the quant trader may well find previously available opportunities on the sell side restricted. But quant trading jobs will not go away; they will simply move to another venue. In addition to earning their keep for the firms that employ them, they provide valuable liquidity to the markets. Quantitative traders are, in large part, the drivers behind electronic trading which continues to grow and develop. But, even on the sell side, quantitative roles will continue, but they will evolve. Developing dark pool and grey pool environments and improved price optimization techniques for transactions are examples of the forms this evolution will take. Quant trading may also involve building instantaneous hedging systems and the automation of the hedging processes. Quant traders can also work on structured products, using programming to identify prospective assets to substitute into and out of the original structure.

Aside from the sell side, quant trading can involve any strategy that the trader can develop. Here the focus is on creating profitable trading opportunities. Trading strategies can vary from high frequency approaches that profit by providing liquidity, to those that operate on a signals basis to generate buy and sell orders to capture trends and exploit pricing inefficiencies. The methods and processes that drive these models are only limited by the creativity of the trader programming the strategy.

The existence of quantitative trading strategies, which now drive an extraordinary percentage of stock market volume, creates a demand for expertise among risk management departments, central bankers, and regulators. These people will be involved in either reverse-engineering the processes used or in developing metrics that assess the performance of the strategies. Given that the quant trading strategy will typically run automatically, pressure is placed on risk management and reporting to fully comprehend the trading methods that are employed and in determining what is critical to maintaining confidence in the system.

COMPUTER PROGRAMMING SKILLS

While it is only a prerequisite for specific roles within the discipline, it is important to address computer programming for financial engineers interested in the development and the maintenance of models. In the most quantitative of roles utilizing financial engineering skills, C++ remains the mainstay of programming and is the most frequently observed programming requirement within job postings. Given the complexity of working within C++ it is not uncommon for financial engineers to write code using Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) for quicker results. The relative importance of each will depend on the nature of the programmer's position. If the quant is expected to create quick, prototype models that can be used within a short time frame, programming in VBA will be more likely. The importance of the ability to create financial engineering tools within the Excel VBA environment should not be underestimated.6 It immediately dovetails with a universal piece of software.

For more complex and stable models, coding will most commonly be in C++, or, alternatively, C# (pronounced “C sharp”), or Java. Fortunately, there are significant overlaps between the three languages. Understanding C++ will better prepare a financial engineer for working with legacy models, as the language has been in use for longer than most Masters of Financial Engineering (MSFE or MFE) candidates have been alive, and it typically embeds better with other systems capabilities. Given that many roles will involve inheriting models that need to be migrated to a more stable environment, the ability to program in C++ is valuable.

For work between full development and Excel-based functionality, there are a number of programming skills that are in demand at financial firms. SAS and SQL are commonly applied for accessing the array of databases within the institutions. MatLab is sometimes applied for intermediate coding work, but it is less common and will not be available at all firms.

CONCLUSION

The job of any two financial engineers is very unlikely to be the same, and can often vary significantly, even within the same firm. We hope that the tables included in this chapter (2.2–2.7, following) help financial engineering students and graduates of financial engineering programs to navigate through the wealth of opportunities available to them, and assist them in identifying the subtle differences between job postings.

What is most important, however, is the asterisk on each of the tables (i.e., “* Incomplete Listing”). The listings provided in this text are incomplete, with many more potential paths available to candidates. Much as physicists never saw “quantitative analyst” among their potential career paths just a few decades ago, the opportunities that will be available to those entering financial engineering today will be unrecognizable when compared to those opportunities available in the field's infancy, and considerably beyond those captured in this chapter. What is apparent is that the roles that utilize the skill sets that financial engineering students acquire will continue to increase.

NOTES

1. For example, mathematical finance programs are a subset of financial engineering programs. Similarly, risk management programs are a subset of financial engineering programs.

2. Based on 150 programs, the median number of candidates in current class sizes from the Financial Engineering Program Survey was 36 students.

3. There are over 250,000 members of PRMIA and GARP, the leading risk management professional associations. Allowing for overlap, with consideration that many professionals do not join these Associations, makes 750,000 a somewhat conservative estimate, especially when risk can be a small component of a role, and considering that both Associations have a Financial Services bias.

4. Search performed using Manta.com. Also identified were 190 banks within the United States that met these metrics.

5. PerTrac Hedge Fund Database Study, 2009. Morningstar tracks 8,000 Active Hedge Funds.

6. Excel is a trademark of Microsoft Corporation.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Spencer Jones is currently an associate at SBCC Group, where he has worked on projects including bank restructuring, structured credit portfolio analysis, and municipal risk management. From 2005 to 2007 he was a risk manager in Barclays Treasury, responsible for risk management across two divisions of the bank, including two M&A projects. From 2000 to 2004 he was an Analyst with HBOS, working in Asset & Liability Management developing risk models. He received an MBA, with distinction, from New York University and an MA in Economics with First Class Honours from the University of Edinburgh.