Chapter 12

Thoughts on Retooling Risk Management

INTRODUCTION

Risk Management is one of the largest academic and practitioner fields within financial engineering. Broad and specialty roles—and often complete departments that focus on risk—exist in tens of thousands of financial and non-financial firms around the world. Areas of practice and, indeed, whole firms have been established to service the risk management community. These include consultants, specialty advisors in accounting firms and law firms, software providers, data vendors, broad stream and specialty media firms, and educational organizations from universities to executive education and conference providers. Risk management draws on core theoretical principles in pure and applied mathematics, finance, economics, accounting, law, psychology, behavioral finance, and the physical sciences, among others. Not only has risk management established itself as a large, permanent field, but also it often takes center stage during times of crisis.

Analysis and discussion of how risk management practices may have contributed to the financial crisis are inevitable. Why were so many firms and customers allowed to become so highly leveraged? How were some lending standards allowed to slip to enable subprime or other loans without proper documentation? How did some banks and broker dealers, and the financial services industry as a whole, become so exposed to single risk factors such as house price inflation? Risk Management practices find themselves in the spotlight outside the financial world as well. Was the BP Gulf oil spill avoidable? Were risk calculations incorrect, or were risk management practices weakened? Were building codes ignored, or were there flawed assumptions or sign-offs that contributed to the loss of life in major earthquakes or mud slides in places such as Haiti and China? The postmortem is necessary both to assess the damage caused as well as to provide valuable lessons for the future.

Major risk incidents do not necessarily point to a major failure in risk measurement or risk management. It is natural for managers and executives to seek a culprit. Risk model flaws, policy weaknesses, mistaken assumptions, over-leveraging, greed, and myopia were named as culprits in other crises ranging from the savings and loan crisis to the 1987 stock market crash to the bursting of the dot.com bubble to the Asian currency crisis to the unwinding of LTCM. The need for geographically diversified backup and failover facilities plus detailed disaster plans were “unforeseen” culprits after the September 11th terrorist attack in the United States; this was despite the fact that such preparation is well-embedded in other countries in the Middle East and the United Kingdom. Regulators, supervisors, and others cited their own culprits, such as procyclicality of accounting treatment and risk management benchmarking.

On many occasions risk managers spoke up about issues, only to find that their warnings were not heeded. Examples have been featured in the mainstream media regarding whistleblowers at companies such as Lehman Brothers Holdings, Inc., Fannie Mae, HBOS, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, Washington Mutual, and Royal Bank of Scotland to name a few.1 In some cases, whistle-blowing staff, and even those that resisted transactions they perceived to have excessive or insufficiently compensated risk, have found themselves shunned, silenced and—in several cases—forced to leave the firm (either by the firm or through their own moral standing). One high-profile case has been that of Matthew Lee, a Lehman Brothers employee who went to extensive lengths to report his concerns regarding “repo 105”; a practice in which the firm reported overnight security transactions as short-term loans, reducing the leverage appearing in financial statements.

In other circumstances, Boards of Directors and Supervisors during post-loss reviews were shocked to find that, upon review, common sense had been cast aside and that “stress” tests were far from stressful. It is common human nature to relax—perhaps for risk oversight to wane—during prolonged good times of growth and wealth. Alan Greenspan's “Irrational Exuberance” was aided and abetted by the relaxation of risk controls. For example, many banks are currently in the process of liquidating their private equity, residential mortgage, or commercial real estate portfolios at significant haircuts. These portfolios were built up on the basis of generating solid returns. The banks wanted to have their own large returns, in some cases believing that an equity stake in a deal or the equity tranche of a structured note might increase their chances of providing loan facilities or additional services to the firms. To enable this, some banks adjusted their risk appetite policy to allow them to increase level 3 (illiquid) asset holdings in light of the projected earnings potential.

In July 2007, Chuck Prince, CEO of Citigroup, famously spoke on the topic of subprime mortgages. “When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you've got to get up and dance. We're still dancing.” This quote has unsurprisingly increased in profile over the intervening years as the concern forming the basis of the question proved to be prescient. Interestingly the second part of Mr. Prince's response to the Financial Times journalist has not gained a similar profile. “The depth of the pools of liquidity is so much larger than it used to be that a disruptive event now needs to be much more disruptive than it used to be. At some point, the disruptive event will be so significant that instead of liquidity filling in, the liquidity will go the other way. I don't think we're at that point.”2

From this one quote and subsequent coverage we gain a valuable insight and reflection on how risk control and management operated at Citigroup at the time. It seems that someone may have raised concerns regarding the market, specifically liquidity; be that liquidity in the origination and distribution part of the market, or in the secondary market for trading holdings. Also, it seems the concerns may have reached business executives (or that the executives had concerns of their own), at least in some capacity. An important question is whether these concerns carried less weight than other drivers to do business (for example, a desire to create asset growth, market share, or earnings). The “Tone at the Top” of an organization is critical to answer such questions. The Citigroup story is not unique. As the post-mortem of the financial crisis continues, ever increasing numbers of risk managers and others who tried to express concerns are identified.

It is within this context of lessons learned from the credit crisis that we approach the questions of whether and how to retool risk management. Some lessons are new while others may only be described sadly as history repeating itself. It is apparent that even where things went right—for example, some identified and tried to speak up about the Madoff fraud, others challenged questionable accounting practices or spoke up to insist levels of risk in some mortgages and CDOs far outweighed the “additional” yield—things still wound up going horribly wrong. In such cases the risk managers were not caught off guard by these events; tragically, they could not get their own organizations or others to heed their warnings. Yet in other cases, risk models and frameworks succeeded in providing warning signals, some of which resulted in reformative action.

In this chapter we describe three actions that we see firms taking now to retool risk management:

1. Revisit the Tone at the Top of the Organization

2. Conduct a Board Level Review of VaR and Stress Testing

3. Add Warning Labels to Risk Reports

As we discuss, all three of these actions can provide valuable results for financial and non-financial firms alike.

REVISITING THE TONE AT THE TOP OF THE ORGANIZATION

In any organization there are few people who share the experience of the board of directors. The role of the board necessitates a wealth of experience. The board's position and existence offer the opportunity to set the tone at the top of the organization. The credit crisis has underscored the need to do so for many. In the board's discussion of the “tone at the top,” common questions around the globe have been: Did our firm set overly aggressive targets? Did our firm allow overly lenient accounting treatment? Did our firm miss or ignore important warning signals? What could our firm have done to avoid losses? Did we ignore excessive profits or growth that preceded losses? How can the board work more effectively with the management and the risk management of the organization? Did the firm's compensation practices encourage or facilitate poor decision making on a risk-adjusted basis? What changes do we need to make going forward?

During the credit crisis, there have been ample cases where individuals have either chosen to back down, left a firm, or found themselves forced out (either literally, or by sudden reassignment). As these have come to light, boards have asked the additional question of whether this happened in their firm. Clear action plans for approaching these cases are required to ensure that any and all concerns reach the appropriate audience before being addressed, closed down (i.e., do not have merit), or escalated as set down by the tone at the top.

Important questions that drive the organization benefit from the board's role. For example, “once in a hundred year” events are observed to occur in the financial markets every year. Should a large financial firm operate with the expectation that each and every year it will need to have capital on hand to weather 100-year storms, or should the firm operate assuming such events are rare? Should the firm have a risk appetite statement? If the firm has someone in the role of chief risk officer or head of enterprise risk management, should this individual play only an oversight role or a larger strategic and advisory role? Should the risk appetite and risk procedures, practices, and controls be approved by the board?

The tone at the top is also critical to provide continuity where necessary in firms. Individual career paths have increased in their transiency between roles and firms. Given this context of shifting levels of experience, combined with the increased appointment of individuals with very specific specialist skills in the quantitative finance field, risk management functions can benefit greatly from the extensive perspective and experience of both senior management and the board. The tone at the top is also critical to guard against the human and organizational tendency to focus on the most recent issues at hand.

The Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation (CSFI)3 produces a biennial report, titled “Banking Banana Skins,” that focuses on the main risks facing financial Institutions. From a survey of bankers, regulators, and industry observers, the report compiles a list of the top risks facing the global banking industry. Over the past decade, outside of the stable years (2004–2007), it is not uncommon to see new risks come into the spotlight as the report's major focus. For example, business continuity became a high priority in 2002 in the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks. More recently, liquidity (2008) and political interference (2010) became the highest priorities, with credit spreads also placing high on the list. None of these risks had placed among the top 30 risks in previous surveys. The behaviors in the “risk concerns list” reflect a scare-of-the-moment mentality. Following the collapse of Barings Bank in 1995, all institutions reinforced their efforts to place safeguards against rogue traders. However, within a few years, rogue trading dropped to a level of low concern or did not appear on the list of top risks by respondents. Seven years later, when rogue traders had become a minor concern for risk divisions relative to items such as business continuity, Allied Irish Bank suffered a large loss from a rogue trader. Risk managers then again elevated rogue trading to a high concern, only to later let it again slip down the list. A further seven years passed, and Jerome Kerviel of Société Générale was discovered to have committed the largest rogue trader event to date. The tone at the top leads the organization not only in the ethics and business practices of the firm, but also in the firm's risk management focus. It is up to the board to set the tone as to whether material potential risks are to be less actively or no longer monitored—or whether new material potential risks are to be taken—without raising these to the board.

The tone at the top is equally important to limit rash decisions to exit activities that may accompany unexpected loss-taking. Given the events in the subprime meltdown, analysis of losses may be used by some to argue for an exit from the market for all securitized or financially engineered products. For financial institutions to continue to perform and manage risk well, some form of market for securitized products and asset-backed (including mortgage-backed) securities is likely to remain. Continuing activity in these markets with appropriate risk controls and risk-adjusted return measures may be preferable to limiting the firm's competitiveness.

The inverse of this situation is also true—the tone at the top is critical to limit risk-taking decisions made solely on the basis of good experiences. This has the potential to cause financial downside, compared to the opportunity cost from the restrictive alternative. Experiences that have worked out well for the organization can result in rapid expansion into a market that is not appropriate, extending relationships into areas to which the organization is not well suited, or to increasing risk limits to accommodate larger transactions with clients who have enjoyed success on a smaller scale.

The tone at the top communicated by the board is necessarily different on many dimensions for every senior management team and risk department. While most firms have some inherent capacity to bear many risk types, skill, available capital, regulatory restrictions, risk appetite, and organizational strength will vary. Said another way, different firms can extract a better return on equity from certain risk types and this method of assessment can assist them in focusing on that objective. Such self-analysis and review is critical to the tone at the top discussions. Further, discussions should separate owned risks from those that the institution may actively choose to seek in the future. An organization can then assess new risks as to how they fit into the picture—are these risks we would like to add to our profile? Over time the owned risk profile can be morphed. For example, a previous decision to have 20 percent of assets as prime residential mortgages cannot immediately be removed, but the process for further lending can be adjusted to lower the overall exposure over time. Alternately, business units may be divested or acquired. New risks that may be considered can vary significantly, with the only clear similarity being that the firm can choose whether or not to take each risk on as part of their risk profile.

The tone at the top also sets other important dimensions of the firm's operations. Media attention has been focused upon the compensation structures within financial and non-financial firms alike. Some CEOs and staff were paid millions in bonus payments as recently as 2007, with the firms unable to recoup any of these payments when the business conducted at that time cost billions of dollars in losses in later years. Governments in the United States, the U.K. and elsewhere have taken steps to adjust the compensation structure. For example, the United States inaugurated a “Pay Tsar” for banks supported by the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and inserted compensation into the Financial Reform Act, whereas the U.K. implemented new taxes to redirect high bonuses to the taxpayer.

CONDUCT A BOARD-LEVEL REVIEW OF VAR AND STRESS TESTING

Value at Risk (VaR) gained huge acceptance as a risk measure, particularly after Riskmetrics4 facilitated the provision of key data after 1994. Providing an estimate of maximum potential loss over a given time period, for a given confidence level (the probability of occurrence), the metric provided both suitable rigor for many risk managers and simplicity embraced by many regulators and senior managers. VaR typically was bolstered via stress testing. The stress testing encompassed changing key assumptions, testing outcomes under historically dire market environments, testing outcomes under other scenarios expected to be painful, and evaluating liquidity assumptions among others. Common goals were to determine both how much key assumptions and/or the asset/liability mix could change prior to causing unacceptable forecast losses, and which assumptions, given a small change, might cause a substantial increase in VaR and/or a substantial drain on the liquidity position. With time, VaR was incorporated into many risk management processes; for example, by establishing VaR levels that were to trigger immediate reductions in existing risk positions.

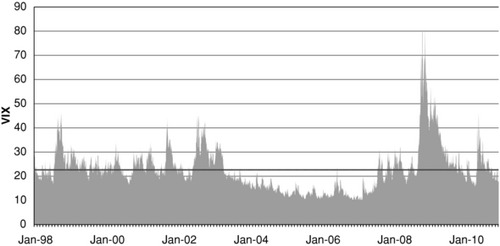

VaR's weaknesses were well-known during the boom period that preceded the crisis.5 As the markets grew increasingly illiquid, VaR-based triggers to exit positions could not be attained. In such cases the assumptions made to calculate a liquidity-stressed VaR had failed. As the markets displayed more and more “highly rare” moves, stress tests were found to be lacking in the degree of stress they forecast. In such cases, the hazards of employing the normal distribution in quantitative finance, given that once-in-a-hundred-year events occur several times each year, returned to the forefront. As stress tests of key assumptions—for example, volatility levels—were reviewed, overconfidence in extended periods of low volatility and easy monetary policy came to the limelight. During the fall of 2008 volatility, as measured by the VIX, almost quadrupled to 80 percent and maintained an unprecedented sustained level above 50 percent for weeks. The behavior of the VIX from January 1998 to September 2010 is depicted in Exhibit 12.1. The trend line depicts the average.

Within the financial crisis we witnessed the collapse of Lehman Brothers, AIG, Ambac, the bailout of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the bailout of Citigroup and General Motors, a TED spread6 that increased by over 900 percent, the failure of many auction markets and the evaporation of short-term credit. Not only were each of these risks considered an extreme outside-odds hazard, but they transpired within a matter of weeks of each other. There are so many major risk events just in 2008 that the experience of $4 gas as oil reached $147/barrel rarely warrants a mention.7

There exists a natural inclination for people to assume a lower probability of rare events than can be justified by statistical analysis. Anecdotal evidence of this can be provided in the form of the hole-in-one gang from the early 1990s.8 A group of British golf fanatics set about placing a number of bets on a hole-in-one occurring during a tournament. Bookmakers, specialists on creating odds for gamblers, provided odds of 20–1 and higher on such an event not occurring. This means that they assumed a maximum of only one hole-in-one event in twenty-one tournaments or less than a 5 percent probability. (Some bookmakers assigned odds of less than 1 percent.) The advantage that the gamblers had over the bookmakers was having performed thorough analysis, rather than trying to arbitrarily place odds on a perceived outside chance. The analysis had shown that the likelihood of a hole-in-one in a major tournament was nearer to even odds. By recognizing the bookmakers inclination to consider certain items less probable than their true chance, the gang earned hundreds of thousands on their gambling (in 1991, three of the four major tournaments had a hole-in-one).

Risk Managers have known for years to ask the question, “When the 99 percent confidence risk level does not hold, how much can we expect to lose?” When the risk figure is breached, as it inherently forecasts will happen, how bad can we expect the event to be?

By way of illustration we can take the example of General Electric (“GE”). As a firm, GE embraced the structure and methodology surrounding VaR with the implementation of Six Sigma to the vast majority of their processes (a form of Total Quality Management). We can consider the assortment of VaR-like models that exist within the firm. For one area, a six sigma, 1 percent, risk event can be a faulty refrigerator. To another area it could be design error that results in an aircraft engine failure, as used on a Boeing 747. Or, as GE experienced in 2008, the 1 percent outside of VaR took the form of extensive losses within their Real Estate division that ultimately required a $3 billion private investor recapitalization. While it is unlikely that these divisions of GE would have a similar VaR dollar amount, it is clear that the scale of the 1 percent events exist on a far more extreme level also. The scale of the extreme event risk can also vary significantly from the level provided within VaR; a one-in-a-million event of aircraft engine failure can result in a very low VaR level, but a very high extreme loss situation.

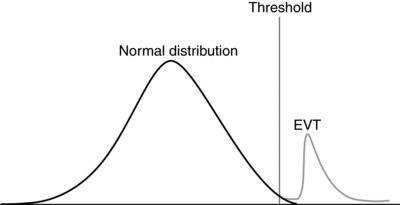

Methods and approaches do exist for both assessing and controlling the tail risk within portfolios. And these advance both in theory and in practice. For example, Extreme Value Theory (EVT) has typically been applied in areas where extreme, low probability events need to be assessed. This is a common technique for assessing natural disasters, but has made some progress into financial risk measurement. Further improvement is necessary as it has become an annual event, if not more frequent, to hear about the occurrence of a once in twenty-, fifty-, or one-hundred year event within financial markets.

The use of Extreme Value Theory to estimate tail events or expected shortfall within financial events has been the subject of academic papers and incorporated into risk analysis over the past decade. Using a Generalized Pareto Distribution to create a fat-tailed structure to estimate excess distributions, a density function is applied beyond a threshold to distribute the tail losses (see Exhibit 12.2).

Exhibit 12.2 Normal Distribution with Extreme Event Distribution Overlay

With the increasing number of tail-events, and the subsequent increased focus of executives to become more comfortable and aware of such circumstances, risk managers are presented with an opportunity to bring EVT and other techniques to the table for consideration.

Vineer Bhansali of Pimco has authored a number of strategies designed to remove tail risk within a portfolio while achieving similar expected returns to a default portfolio.9 The approach, conceived in the context of an equities portfolio, is designed to take increased risk on the investment portfolio sufficient to produce enough extra expected return to finance the hedging of tail risk via the purchase of an out-of-the-money put option on the portfolio. The portfolio is then hedged, to a level, against extreme events by the option. Bhansali's approach to Tail Risk Hedging is not that the option will come into the money, but rather that the occurrence of a tail risk event will dramatically increase volatility. This movement in the volatility surface will increase the value of the out-of-the-money option significantly relative to the premium paid at purchase, whereupon the hedging party will sell out of the hedge.

Extreme Value Theory and Bahnsali's approach to address tail events are but two of the many approaches that exist for risk managers and firms to consider in managing tail risk. Additional approaches are discussed in published studies, such as those by the Board of Mathematical Sciences and Their Applications at the National Academies: “Technical Capabilities Necessary for Systemic Risk Regulation: Summary of a Workshop” and “New Directions for Understanding Systemic Risk: A Report on a Conference Co-sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the National Academy of Sciences,” among others.

With respect to VaR and stress testing, one action that can be taken immediately by firms is to ask the board of directors to conduct a review of risk management practices with or without the help of outside advisors. One useful standard is to ask that this review be conducted at the same level of rigor as that used during a review of important forecasts, budgets, and business plans. During such reviews, directors often question key inputs, such as the assumed cost of materials, assumed manufacturing costs, assumed employee costs (including benefits and pension expenses). Directors often challenge key drivers of the outcome such as sales growth, the forecast timing, and degree of success for expansion plans into new markets or geographies, or the assumed synergies that will benefit the bottom line after an acquisition. As new approaches emerge, directors often question whether these are included in the forecast, budget, or business plan. Examples are the advent of new technologies, new hedging techniques, or new providers for items critical to the success of the business. Substantial debate is the norm in board rooms regarding forecasts, budgets, and business plans. Often, the wisdom of board members provides valuable input and improvements to the adopted version of forecasts, budgets, and business plans. VaR and stress testing should be reviewed under similar challenge and debate prior to being approved on an annual basis. Further, VaR and stress testing should be re-reviewed whenever a large unexpected result occurs—whether good or bad.

As the mortgage business accelerated over the half-decade leading up to the crisis, the defined neutrality of non-executive directors reviewing major assumptions within models might have provided the support required for changes. Many risk managers would have recognized that assumptions providing only a 5 percent probability of any downturn in housing were overly optimistic. A policy defining the importance of such assumptions and requiring their approval and discussion by the risk committee could have provided the support risk managers required. Non-executive directors lie outside the earnings-motivated business structure and would bring their knowledge of house prices in the 1990s and previous international collapses (e.g., Japan, United Kingdom).

This wider experience can provide an excellent test of context for any assumptions or stress testing. Stresses of credit spreads within models can be placed in a more historical context. Stresses that seem large in the context of recent history can be scaled to accommodate longer time-frames that more extensive experience can easily recall. Combination scenarios from prior downturns will be better incorporated and tested. Involvement of the risk committee in defining the stresses and assumptions within the models employed should motivate executives to be more involved and in touch with the risk figures that are presented. Involvement throughout the process will enable management to be better placed to ask questions on risk reports and be familiar with the context in which they are provided.

Incorporating the board and executives more fully into the process of risk definition and testing can provide a strong positive feedback loop for risk management. While requiring greater scrutiny and discussion on risk inputs, assumptions, and parameters, developing involvement at the highest level will enable greater understanding of risk reporting and the benefit of experience to complement that held by individuals within risk management. Further, it brings variety to the thought process, benefiting risk managers with the wider perspective provided by the varied experiences of the senior team, while revealing revenue or asset or other growth drivers so these may be agreed at the highest level of the firm.

ADDING WARNING LABELS TO RISK REPORTS

Interpretation is a fact of life for most risk calculations as well as their inputs. What does a “mark-to-market” (“MTM”) price mean? In one firm, instruments may be simple—for example, just-issued sovereign debt or round lots of highly liquid equities traded on major global exchanges, such as the NYSE, FTSE, and NIKKEI—so MTM may be assumed to be close to values at which the instruments may be bought or sold. At another firm, instruments may be more complex—for example exotic custom derivatives, large block positions or private equity investments in emerging market companies—here, MTM begins and ends with numerous assumptions and may be far from values at which these instruments may be bought or sold. As many firms learned as markets plunged in the crisis, the ability to earn profit without realization can be hazardous for the allocation of risk capital. Assets held under MTM delivered strong “earnings” but turned out to be driven by MTM appreciation in markets where liquidity evaporated and sent MTM prices spiraling downward. In the case of many subprime real-estate-linked instruments, as the participants increased, so did MTM values, as demand for these instruments rose. Prices inflated, asset bubbles were created and, for many, cash was not realized while income was booked. IMF studies have identified empirical evidence that MTM accounting encourages procyclicality within banks.10 The “originate loans to distribute/sell the loans” model is an entire business area where numerous regulators and supervisors—as well as the mainstream press—correctly observe that accounting policy and profit motives can collide to encourage subpar risk practices.

As a second example, consider the question, “What does a ‘AAA rating’ mean?” For some instruments it has the widely expected meaning that default risk is remote. Yet in other cases this is not so. For example, the “AAA” tranches of many CDOs defaulted without progressing through interim ratings downgrades, and Auction Rate Securities became illiquid and lost substantial value. These and other instruments did not behave the way many assumed AAA investments behave. Once sought-after investments in “agency” paper went awry as Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae, and other government-sponsored entities tanked and had to be bailed out.

The reliance on the ability to manufacture AAA paper became a core part of some business models. Securitization facilitated a create-to-distribute business model. This model could only work under the assumption that the product would be distributable. Should the assets need to be held on the balance sheet, the risks would remain within the firm. Financial firms reliant on securitizing a production stream found themselves unable to distribute as liquidity vanished over quality concerns by investors. If the firms had not considered this eventuality, they were either forced to immediately reduce lending, or worse, try to sustain increased short-term funding during the liquidity crisis at great expense. Even firms that had operated with caution, had prime quality assets in the pipeline for securitization, or operated using a covered bond program, found that they could not access the market.11 The assumption that the distribution model would continue to operate came at an expense for many firms and for taxpayers. For some firms, the failure of the distribution model came at the expense of their independence or even existence.

As a third example, consider transactions with what were broadly believed to be reliable, credit-worthy counterparties. Many of these turned out differently as firms defaulted and banks got into serious trouble in Iceland, Ireland, the United States, and elsewhere. Many large organizations were impacted by difficulties in identifying their exposure to Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearns, and AIG, among others. Many executives and managers who believed their firms could identify total exposures to major trading parties were almost instantaneously shocked to discover otherwise. As a consequence of understandable difficulties relating to data granularity, location, offsetting transactions, and secondary effects, the necessity for a better alternative compounded. In these cases, counterparty risk manifested at a higher magnitude and greater complexity than projected.

The complexity in counterparty risk was evident in the uncovering of the Madoff Ponzi scheme in 2009,12 highlighting the difficulty of identifying full exposures within the shadow banking system and secondary market funds. Even with a database of counterparty exposures a firm may have significantly underestimated its exposure to Madoff. It is now understood that the numerous feeder funds to Madoff were unlikely to be captured with the first assessment of exposure, with numerous entities operating as a storefront for the fund. Such realities demonstrate a complexity through cross-holdings, fund of fund investments, and numerous other paths to possible exposures. Several fund of hedge funds themselves found they had a similar complexity of potential exposures to untangle.

Yet many risk reports start with such information—MTM, rating, counterparty exposure, among many others—merely as inputs to risk calculations that go on from there. Layer upon layer of assumptions are routinely made—for example, regarding liquidity, volatility, and correlation—in order to produce everything from VaR to stress test results to liquidity and counterparty risk reports. With risk measures based around a framework of probability distributions and consideration of multiple events, the necessary assumptions continue and grow even more complex. Further, as the importance of risk factors change, additional assumptions may be layered on.

With regulatory risk likely to be one of the major risks of the forthcoming decade, single-number risk estimates based on regulatory capital may not be well aligned to the businesses executives will be leading. Such estimates may even be more problematic at times of tight credit or liquidity stress in the capital markets. Based on such changes it is an excellent time to perform a review of such underlying factors to the risk management process.

Sometimes, large organizations are able to perform functions better than smaller ones. Global customer relationship management, increased service through distribution networks, the ability to provide better pricing, and a balance sheet that can accommodate larger, more complex transactions are common examples. Of course, there are also areas where scale has been proven to be disadvantageous, typically in the sphere of certain trading strategies where increased capital serves to decrease returns. Perhaps somewhat counter-intuitively, risk management also falls under the category of areas that may become weakened by scale.

Risk managers, data analysts, and technology professionals are all too familiar with the extensive data processing required to produce timely risk reporting. This is a separate area of yet even more assumptions in the overall risk process. Large-scale business activities, across geographies, time zones, systems, products (from simple to complex), maturities, and counterparties, rapidly become a vast sea of data. Irrespective of the limitations of these base data, the sheer volume of transactions held by an organization at any one time presents enormous challenges.

The complexity and scale of portfolios creates a necessary trade-off for risk management and reporting; to report risk positions expeditiously, such as an end-of-day risk report, data must be mapped through a process of stratification, correlation, and simplification. To provide more accurate reporting (i.e., to incorporate less simplification of the data) often requires substantial additional expense and takes significantly longer, with technology presenting tradeoffs as to the cost and speed at which a risk assessment can be completed. Further, trade-offs made at one time—for example huge simplifications made at a time that a certain activity of the firm was small—may need to be revised to continue to provide accurate risk reports.

However, the issue of operating with summarized data streams is not an issue exclusive to larger organizations. With ever-increasing complexity within securities, the analysis of a single security portfolio can itself force assumptions in correlations, stratification, and mapping. Holding a mortgage-backed security necessitates assumptions on single-loan behaviors based on region, credit score, prepayment behavior, quality of the underlying documentation, and other metrics. A CDO increases the scope and scale of these assumptions by a factor. In assessing the risks within CDO2 (also known as a “CDO squared,” or a CDO within a CDO), synthetic CDOs with substitution rights, tranches with accelerated repayments, the necessity and complexity of assumptions and mappings to be made increase rapidly. In larger organizations, the difficulties of data mapping are compounded when working with these complex securities, with correlations on top of correlation matrices, and with credit spreads simplified and then amalgamated further.

It is critical that the user of risk reports have an understanding as to where simplifying assumptions have been made and how these may impact the quality of the results. Risk departments frequently begin with a careful review of available data, modeling, and assumptions. Data hierarchies, model risk policies, and discussions of the Achilles heel in specific quantitative approaches are often heated debates with productive results within risk management departments. Clearly, successful Risk Officers must determine the right balance of complexity versus simplifying assumptions in the approach. A trade-off exists between a model seeking to be roughly right and precisely wrong. There is a point where assumptions made within the model become a more significant component of the output of the model than the actual exposure being evaluated. Other trade-offs exist as well. Some simplifying assumptions may seem theoretically fine but may create dangerous results in practice. For example, the use of a report that includes output from a model that has a closed-form solution may be expedient for certain theoretical estimates, but may cause losses if used for other purposes.

A common technique employed, as greater and greater assumptions have been agreed and implemented, is to implement mark-to-model reserves. Simply explained, mark-to-model reserves try to estimate how far off results may be, given the assumptions required to use a particular model. As the reader can imagine, this may be difficult not only to evaluate a single model—for example, the model used to estimate the mark-to-market value for a given CDO—but grows increasingly difficult as the results of multiple models are combined to produce results such as for VaR and stress tests.

One action that can be taken immediately by firms is to include warning labels within risk reports. Similar to the practice followed in prescription drug labeling, these would include how the risk report's figures are recommended for use, and dangerous potential applications or interpretations would be clearly displayed. Some risks cannot be successfully combined and therefore should not be combined, nor presented in a manner that will imply that they can. While some of this may be communicated via presentations or in discussions with senior management and the board, labeling may serve to address the types of issues that have been common since the outset of the credit crisis. In particular, questions over whether the limitations of the risk reporting were well understood.

CONCLUSION AND AN ENDNOTE

Based on all of the above, it is our recommendation that organizations (1) revisit the tone at the top, (2) conduct board-level review of VaR and stress testing, and (3) add warning labels to risk reports. These suggestions also may assist in addressing two additional items of heightened concerns in the risk arena: coping with procyclical rules and contagion.

Coping with Procyclical Rules

A shared problem for both risk management and the executives within firms is the procyclical nature of much of the regulatory environment in which they must operate. While Basel III is moving to develop methods to protect against procyclicality, it is unlikely that the committee will reflect the risk potential to the degree that is perceived by many practitioners or management. With management not wanting to deliver boom-and-bust cycles to investors, they can be expected to seek to minimize loss events by developing protection against procyclical behavior. This will likely form the basis of a major component of forward-thinking discussions.

Fighting procyclical behavior is, in part, trying to enforce rules that are contrary to human nature. Buying into asset bubbles in larger volumes is natural if more capital can be made available, as profitable markets are difficult for firms to resist (and in conflict with much of their purpose). Risk management already has numerous tools that can help contend with procyclical behavior. Risk models operating on a long-term investment basis, using Monte Carlo simulations and stress scenarios, can capture the potential risk. For short-term, liquid investments risk management's argument is more difficult and is often contended. More often than not, the side battling to enter the procyclical market wins, with the opportunity to make profit proving seductive.

The IMF recommendations to address the procyclicality include full fair value accounting (to avoid cherry picking of assets), consensus pricing, and reclassification committees for moving assets in and out of held-to-maturity status. The debate over procyclical accounting policy will certainly involve these factors, but will also benefit from risk involvement in other control mechanisms. The Pandora's Box of mark-to-market accounting has been opened, and remains the best identified accounting policy for financial firms at present. Decision rules on fair value adjustments and the method of any circuit breakers applied will involve extensive input from risk management. While Finance will present the opinion of accountancy, the business area will encourage behavior that paints it in the best light. Risk management should develop a role for itself in presenting the risks associated with the reclassification of the assets.

Contagion

An understanding of risk contagion is likely to have a significant influence on how a firm chooses to build its risk profile. Once contagion concerns are taken into consideration, the selection of new assets and risks will adjust to reflect the potential exogenous risks that the firm will become exposed to. The contagious nature of risk is well illustrated by the subprime mortgage debacle. It moved from hedge funds performing repo, to American banks sourcing liquidity, and then on to insurance companies and European banks with minimal subprime exposure. The contagion transcended sectors and borders. IMF studies using Extreme Value Theory have indicated statistically-supportable levels of contagion within U.K. banks from international and domestic stresses.13 The analysis of risk contagion has become an active area in finance research, with the Bank of International Settlements and other authorities assessing contagion within banking, sovereign debt, and other markets.

Consideration of risk contagion could motivate an organization to avert speculative bubbles. If liquidity is managed and monitored well, the risk contagion factors of many competitors holding large asset portfolios that are similar in characteristics would be of concern. In 2006, as the mortgage market was at its height, the threat of risk contagion as a result of the mortgage market was high; banks, the shadow banking system, and insurance firms all had extraordinary exposures to housing. With an ability to capture and monitor the market for contagious risks, a firm would (hopefully) be able to notice this trend and seek to reduce its own position in the market. In effect, through monitoring and controlling the exposure to risk contagion, the firm is seeking to diversify itself from its peers.

The diversification from other institutions by way of the type of assets and positions that are held will better enable firms to ride through financial storms. Awareness of the level of exposures that create systemic exposure within the organization could become a valuable component for setting and evaluating risk appetite. Managing the risk of contagion to the firm alongside exercising judicious control of liquidity will best enable an organization to continue in normal business through difficult periods, without having to significantly adjust the business model applied.

The proposals for Basel III, currently in draft regulation form, seek to incorporate considerations of leverage, counter-cyclicality, counterparty risks, and liquidity provisions. Though the expansion to recognize increased numbers of risk factors is welcomed, financial risk managers must be wary of repeating past errors and focusing only on the regulated risk factors. They need to consider all factors, regulated and unregulated, that present risk to the organization.

The critical component of this proposed approach to risk management is that risk management does not need to be torn down and completely rebuilt. The capacity, ability, and methodologies applied within the vast majority of firms to manage risk successfully exist already. Further, many of the models within these institutions perform well at their defined task. Instead, the focus should be placed on where no models are defined. This may be a result of a lapse in communication such that management is not specifically clear on the coverage provided by the risk models and the reports that currently exist. It certainly exists in areas that have not been fully analyzed, or perhaps have not ever been analyzed at all.

As organizations begin to work towards achieving improved transparency (both in reporting, assumptions, and risk measurement), risk experts can work with the risk committee to ensure that assumptions are reviewed by appropriate parties. Many assumptions will remain under localized control, where risk experts are the appropriate individuals to consider the variables. Key drivers of the risk picture and risk profile of the firm, however, would benefit from the involvement of directors.

NOTES

1. See Corkery (2010), Overby (2010), Prenesti (2009), BBC News (2009), Hudson (2010), Wilchins (2010), Chernoff (2009), Gordon (2010), and Bremer (2009).

2. See Nakamoto and Wighton (2007).

3. The CSFI is a London-based think tank established in 1993.

4. RiskMetrics is a risk subsidiary that was rolled out from J.P. Morgan to market its Value at Risk modeling and advisory.

5. See Beder (1995).

6. The Treasury to LIBOR differential for similar maturities.

7. We also fail to mention Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley becoming bank holding companies, GE requiring a private bail out, the bankruptcy of 43 companies with over $1bn in assets. See Altman and Karlin (2010).

8. See Carter and Simons (1993).

9. See Bhansali (2010).

10. See Novoa, Scarlata, and Solé (2009).

11. Covered Bond Programs are an alternative to securitization where the assets are ring fenced but remain on the balance sheet of the firm rather than being transferred to an SPV. While not providing capital relief like the securitized alternative, the Covered Bond provides liquidity to fund mortgage issuance. The buyer of covered bonds has the explicit support of the balance sheet of the firm, providing more assurance.

12. The Madoff scheme was uncovered in late 2008, but the full extent of it was not understood until 2009.

13. See Chan-Lau, Mitra, and Ong (2007).

REFERENCES

Altman, Edward I., and Brenda Karlin. 2010. “Special Report on Defaults and Returns in the High -Yield Bond and Distressed Debt Market: The Year 2009 in Review and Outlook.” Working paper, February 8.

Beder, Tanya. 1995. “Value at Risk: Seductive but Dangerous.” Financial Analysts Journal (September–October): 12–24.

Bhansali, Vineer, and Joshua Davis. 2010. “Offensive Risk Management: Can Tail Risk Hedging Be Profitable?” PIMCO, (April): 1–14.

Bhansali, Vineer, and Joshua Davis. 2010. “Offensive Risk Management II: The Case for Active Tail Risk Hedging.” Journal of Portfolio Management 37:1, 78–91.

Bremer, Jack. 2009. “RBS executives claim they were intimidated.” The First Post, March 23. www.thefirstpost.co.uk/46802,business,rbs-executives-claim-they-were-intimidated.

Carter, John, and Paul Simons. 1993. Hole-in-One Gang. Monrovia, MD: Yellow Brick Publishers.

Chan-Lau, Jorge A, Srobona, Mitra, and Li Lian Ong. 2007. “Contagion Risk in the International Banking System and Implications for London as a Global Financial Center.” Working Paper 07/74, International Monetary Fund.

Chernoff, Allan. 2009. “Madoff whistleblower blasts SEC.” CNN Money, February 4.

Corkery, Michael. 2010. “Lehman Whistle-Blower's Fate: Fired.” Wall Street Journal, March 15.

Gordon, Marcy. 2010. “Risk officers say they tried to warn WaMu of risky mortgages.” USA Today, April 13.

“HBOS whistleblower probe demanded.” 2009. BBC News, February 11.

Hudson, Michael W. 2010. “Mortgage Meltdown: How Banks Silenced Whistleblowers.” ABC News, May 11.

Nakamoto, Michiyo and David Wighton. 2007. “Citigroup Chief Stays Bullish on Buy-Outs.” Financial Times, July 9.

Novoa, Alicia, Jodi Scarlata, and Juan Solé. 2009. “Procyclicality and Fair Value Accounting.” Working Paper 09/39, International Monetary Fund.

Overby, Peter. 2010. “Consultant: Federal Aid Program Failing Homeowners.” National Public Radio, August 6.

Prenesti, Frank. 2009. “HBOS whistleblower threatens more disclosure-report.” Reuters, February 15.

Wilchins, Dan. 2010. “Former Citi Manager's Testimony Helps Lawyers.” Reuters, April 9.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Tanya Beder is currently chairman of SBCC in New York and SBCC Group Inc. in Connecticut. SBCC, founded in 1987, has a broad base of hedge fund, private equity, traditional investment management, financial services, and corporate clients. From 2004 to 2006, Tanya was CEO of Tribeca Global Management LLC, Citigroup's USD 3 billion multi-strategy hedge fund, and from 1999 to 2004 was managing director of Caxton Associates LLC, a USD 10 billion investment management firm. She serves on the National Board of Mathematics and their Applications as well as on the boards of a major mutual fund complex and family office. Tanya has taught courses atYale University's School of Management, Columbia University's Graduate School of Business and Financial Engineering, and the New York Institute of Finance. She has published in the Journal of Portfolio Management, Financial Analysts Journal, Harvard Business Review, and the Journal of Financial Engineering. She holds an MBA in finance from Harvard University and a BA in mathematics from Yale University.

Spencer Jones is currently an associate at SBCC Group, where he has worked on projects including bank restructuring, structured credit portfolio analysis, and municipal risk management. From 2005 to 2007 he was a risk manager in Barclays Treasury, responsible for risk management across two divisions of the bank, including two M&A projects. From 2000 to 2004 he was an Analyst with HBOS, working in Asset & Liability Management developing risk models. He received an MBA, with distinction, from New York University and an MA in Economics with First Class Honours from the University of Edinburgh.