Chapter 27

Portable Alpha

INTRODUCTION

Portable alpha is a form of financial engineering used by institutional investors and others in their portfolios. Portable alpha gained popularity during the late 1990s in the aftermath of the Asian currency, Russian commodity, and the Long-Term Capital Management crises. Market conditions at the time—low volatility, flush liquidity, tight spreads, low risk premiums, and high confidence in the markets—led investors to seek new ways to boost investment returns. Portable alpha was designed to provide that extra return.

Portable alpha was considered by some to be quite a major development, and was grouped along with some of finance's greatest achievements: “Every now and then, there is a development in the world of finance that results in a major paradigm shift. Examples include the introduction of present value as a tool in financial decision making, the Modigliani-Miller hypotheses regarding capital structure and the introduction of modern portfolio theory in investing … [and] the use of various portable alpha financial engineering techniques to raise returns, reduce portfolio volatility, and/or achieve better asset-liability matching.”1

Portable alpha can be structured a number of ways. During its first decade of use, for most institutional investors that embraced it, portable alpha was a success story. This group included well-known asset managers at firms such as Harvard Management, John Hancock, Fidelity, Goldman Sachs, Solomon Brothers, Janus, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley. But as the credit crisis took hold in 2007, and market conditions changed to higher volatility, lower liquidity, wider spreads, higher risk premiums, and lower confidence in the markets, some institutional investors wound down their portable alpha programs, dismantled the beta portion, or purged the alpha-related leverage. These included asset managers at entities such as the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS), the Pennsylvania State Employees Retirement System (SERS), the Massachusetts Public Reserves Investment Management Board (Mass PRIM), and the Fire and Police Pension Association of Colorado.2 So, in a little over a decade, portable alpha has been through birth, grew up to receive accolades as a major development in finance, and faced death in the eyes of some important investment managers. But recently, portable alpha has experienced a rebirth. In this chapter we discuss portable alpha and some of the key pluses and minuses of portable alpha.

WHAT IS PORTABLE ALPHA?

To define “portable alpha.” first we need to define “beta” and “alpha.” Beta is a measure of how much an investment position moves with the market. For example, betas of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 imply that the position will move half as much, the same as, or twice as much as the market, respectively (whether up or down). Alpha is a measure of how much an investment activity is non-correlated and unsystematically related to the market. Hence, alpha is a measure of the degree to which an investment activity (or manager) generates returns that outperform the market for a given period of time. A natural question is “which market?” The market is defined by the investor. It may be a broad equity market index, for example the S&P 500, the Russell 1000, the FTSE, the NIKKEI, the top 100 Euro or Asian or global stocks, the top energy or top technology stocks, and so on. It may be a broad bond market index, for example the Lehman Aggregate Bond Index [now Barclays], a composite market index such as ARIX, MSCI, a hedge fund index, or a custom index, for example credit spreads. Another approach is to “strip” beta from a successful active manager's returns, thereby leaving the alpha as a residual. For example, the investor has an investment in a manager who trades a broadly diversified portfolio of U.S. equities and achieves net returns of the S&P 500 plus 200 basis points. In this case, the investor would enter an equity swap paying the S&P 500 and receiving Libor, yielding net returns of Libor +200 basis points. The investor then may combine this return with another equity swap, for example paying Libor and receiving a bond index to achieve a return of the bond index plus 200 basis points. In this example, the alpha of the equity manager (200 basis points) is ported to a bond investment.

Portable alpha is the practice of separating alpha from beta by engaging in investment activities with a return pattern that differs from the market index from which their beta is derived. The purpose is to add low correlation sources of return to a portfolio, while maintaining the desired asset allocation (systematic beta exposure). There are three common ways to implement portable alpha:

1. Alpha Overlay

In this approach, the investor enters into a total return swap, typically paying a short-term interest rate in exchange for alpha performance. The alpha performance may be achieved via one or more hedge fund managers, or via an investable hedge fund index.

2. Alpha Transport

In this approach, the investor enters into a derivative transaction, typically paying a market index in exchange for the performance of one or more “alpha” managers, or the performance of an investable “alpha” index.

3. Alpha Replaces Beta

In this approach, the investor typically sells beta exposure and buys a pure alpha investment. In this implementation, the asset allocation of the portfolio most often changes. Rather than earning alpha on top of the systematic beta exposure, the alpha investment replaces the beta exposure.

The goal is to create a non-correlated strategy designed to increase risk-adjusted returns, by increasing the expected generation of “alpha” regardless of asset class. Approaches (1) and (2) allow investors to invest in high-alpha strategies while maintaining the desired strategic asset allocation in the traditional equities and fixed income markets, among others. One common approach is to source alpha via an investment in hedge funds, fund of hedge funds, and/or investable hedge fund indices, such as those calculated and published by Hedge fund Research (HFR), Credit Suisse (CSFB), MSCI Hedge Invest Index, Standard & Poor's (S&P), FTSE, and so forth.

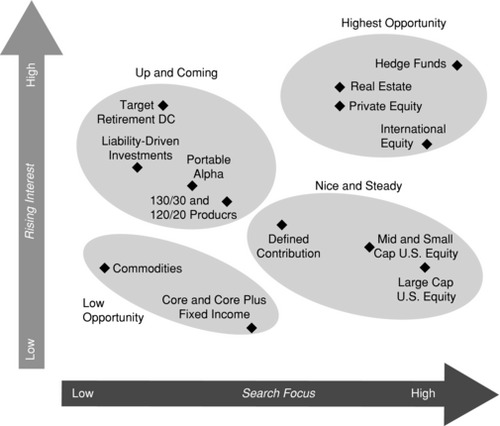

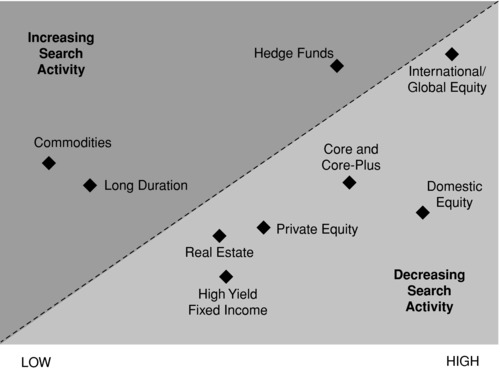

In their 2007 Consultant Search Forecast, covering expected trends in institutional consultant searches, Casey Quirk place Portable Alpha in the “Up and Coming” section, indicating that, although it may not represent a search focus yet, it sees “rising interest in conducting search activity.” However, in their 2010 Product Opportunity Matrix, portable alpha has disappeared from Casey Quirk's categories for “Increasing Search Activity” or “Decreasing Search Activity.” See Exhibits 27.1 and 27.2.

Exhibit 27.1 The 2007 Casey Quirk Search Opportunity Map

Exhibit 27.2 The 2010 Casey Quirk Product Opportunity

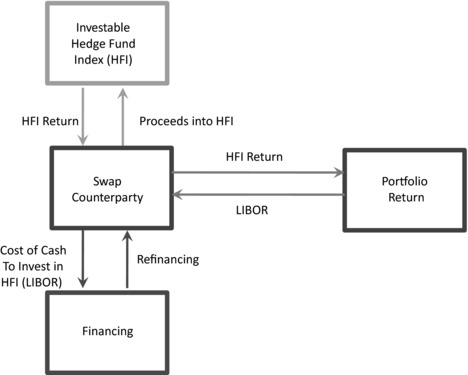

Exhibit 27.3 Implementing Alpha Transport

Illustration: Implementing Alpha Transport (AT)

Exhibit 27.3 illustrates a common form of the alpha transport transaction.

We now provide numerical examples to illustrate how alpha transport works. Assume that the investor places 20 percent of the notional amount of the existing portfolio into an alpha transport strategy using an investable hedge fund index. We provide two cases, depicted in Exhibit 27.4, one in which the return of the Hedge Fund Index (HFI) exceeds the Portfolio Return and one in which the reverse is true. All other factors are held constant. The assumed returns and cost of capital are illustrated for the two cases. A note of importance—both of these examples assume that the correlation between the HFI and portfolio return is insignificant over the life of the transaction.

Exhibit 27.4 Two Hypothetical AT Performance Outcomes

| HFI > Portfolio | Portfolio > HFI | |

| Notional invested in alpha transport strategy | 20% | 20% |

| HFI Return | 10% | 2% |

| Portfolio Return (PR) | 6% | 6% |

| Libor | 3% | 3% |

| Swap Return (HFI Return—Libor) | 7% | −1% |

| Swap Return × Notional invested (AT) | 1.4% | −0.2% |

| Return using alpha transport (PR + AT) | 7.4% | 5.8% |

As the example illustrates, alpha transport is not attractive in all scenarios. The scenario on the right, which holds all assumptions constant other than reversing the relationship between the Portfolio Return and the HFI Return (PR is 4 percent lower and higher than the HFI Return, respectively, in the two scenarios), illustrates how alpha transport may in some cases lower the return of the investor's portfolio. In addition, during the credit crunch that began in 2007, some alpha transport participants found that collateral calls by the swap counterparty placed further burden on the investor.

THE APPEAL OF PORTABLE ALPHA

What is appealing in portable alpha structures in an institutional investment context? In theory, alpha overlay and alpha transport allow investment returns derived from asset classes of strategic importance to be separated from those derived from trading and portfolio management skills. From the point of view of most institutional investors, the first group of investments represents “beta”—a strategic asset allocation mix defined in the medium-long term and infrequently modified. In contrast, “alpha” involves actively-managed portfolios of assets: definitions are abundant, but a relevant one in this context is that the resulting alpha portfolios should have desirable return and risk features, with low exposure to the investor-specific set of “beta” assets. An alpha, so defined, may include assets whose underlying risk can be diversified, as in the original Sharpe (1964) notion, but also managed portfolios of “beta” assets, such as tactical assets and currency allocation programs. They could even include actively or passively managed allocations to one or more sets of assets not included in the “beta” set, such as commodities and real estate. What matters here is less what is academically pure, and more what is relevant and acceptable to each investor within the context of their asset allocation.

While many defined benefit pension plans embraced portable alpha, because it offered freedom at a targeted risk budget to select alpha where it was best or difficult to obtain (for example, commodities), many endowments shunned the concept. Endowments often budget greater volatility than pension funds and seek the best sources of return for this higher risk budget—this may not justify a portable alpha strategy.

The question is whether, for a target volatility, returns are higher with a portable alpha strategy or not. The answer may be different in a low volatility, high liquidity, low spread environment than it is in a high volatility, low liquidity, high spread environment. Further, in very strong directional markets, portable alpha may lag both on an absolute return basis and on a risk-adjusted return basis. More importantly, strategies such as portable alpha may be most challenged at times of transition from one state to the next in trading the capital markets.

The portable alpha idea is appealing, as separating these components allows for independent risk budgeting, performance attribution, and risk control of “alpha” and “beta” investments. Portable alpha depends heavily on defining the expected outcomes ex-ante (i.e., before occurrence). But if the expected ranges of volatility and ranges of correlation (i.e., volatility of volatility and volatility of correlation) are accurately predicted, sound transportable investing results. In the recent higher volatility and lower liquidity environments, it may be more difficult to formulate expected outcomes. By contrast, more traditional “commingled” alpha/beta investments, such as an actively managed long-only equity portfolio, allow only partial, and usually unsatisfactory, levels of separation through techniques such as tracking error control. This often constrains the alpha source to ensure beta exposure.

Practical Implementation Issues

In practice, even the simplest alpha structure requires attention to issues not usually encountered in more traditional portfolio management setups. Portable alpha structures usually result in additional investor exposures to assets, and/or markets that were not in the original allocation mix. A good example is provided by one of the earliest forms of portable alpha that has been used by institutional investors from as early as the mid 1980s: the replication of an active listed equity portfolio via an index portfolio or index futures contract, with a dollar-neutral long/short portfolio overlay on top (type one, or “Alpha Overlay”).

This type of structure appears straightforward: in the end the weight mix of any actively managed portfolio whose performance is measured relative to a benchmark is, algebraically, the sum of the underlying benchmark plus a long/short portfolio with same-value sides (in absolute terms) by construction. As professionals familiar with this structure will know, implementing this “replicating” active equity structure requires attention to at least two additional issues.

The first issue is the potential for “net short” positions. That is, a “short” weighting in the active long/short portfolio that exceeds the corresponding “long” weighting in the benchmark, leaving the underlying investor with a net short liability. This may not be allowed or may be undesirable to the underlying investor. But eliminating it requires imposing constraints in a space, that of smaller-cap stocks, which is often where active managers seek to add value, and would ultimately re-introduce the benchmark drag that the portable alpha structure is supposed to eliminate in the first place.

The second issue is that the underlying active “alpha” manager seeks short exposure through stock borrowing and short selling. These activities involve additional technical, credit, and demand/supply exposures that would not be required in the underweight/overweight context of a traditional long portfolio. Each of them, in turn, requires proper management, and consideration needs to be paid to issues such as margining and sourcing of short names.

Additionally, it may not be possible to separate “alpha” and “beta” investments, or to obtain sufficient exposure to the long and short side of the “alpha” portion. Implementing the beta exposure via an index may be more expensive (as we have seen recently) in times of tighter liquidity, as also may be the cost of establishing swap positions to offset the requisite exposure. Thus, the economics available to direct investors, or to managers who build the strategy to offer to investors, vary significantly according to the state of the market environment. Many emerging equity markets do not allow short-selling, or limit it significantly. In these cases, it is often possible to short sell an index or futures contract against the long holdings of the portfolio, but the short-side weights are limited by the underlying index, just as in long-only benchmarked portfolios. This may be even more difficult in times of market dislocation, as we have experienced recently. Or, as until recently for real estate, and currently the case for the newer forms of alternative investments, a representative index and/or index contracts capturing the relevant “beta” may not be available separately from active management of the underlying assets.

When a solution is available it usually involves structuring by banks and, increasingly, by other specialized intermediaries. In all cases, issues of liquidity and/or counterparty/credit risk arise that need to be properly highlighted and monitored.

Critical Areas in Implementing Portable Alpha Structures

It is not difficult to show that, if properly constructed, a portable alpha structure is superior to more traditional “commingled” alternatives. It also is not difficult to show that, if the market environment changes substantially, a traditional “packaged” beta plus alpha structure may exceed the returns available via portable alpha due to the increased friction, basis risk, and transactions costs. For decades now, specialized intermediaries have been providing solutions to manage the additional exposures associated with portable alpha strategies and their associated risks. They also provide technical expertise in contract structuring. But the additional exposures nonetheless need to be identified and properly managed. These include:

- Proper identification of the beta in the investment portfolio pre-implemen-tation of portable alpha;

- Proper identification of any beta in the alpha generator;

- Proper identification of the correlation of the preceding two items, plus stability of this correlation in different market environments;

- Legal, structuring, credit, and corporate governance of vehicles to manage the financial risk and legal liability arising from short positions;

- Liquidity and counterparty risk when alpha/beta separation is obtained via structuring through OTC, or through contract where liquidity, under normal and stressful circumstances, is unlikely to match that requested by the investor;

- Evaluation, monitoring, and management of additional risk exposures (shorting, stock lending, derivatives, margining/leverage) involved in the structure;

- Stability of volatility and correlations relative to predicted levels;

- Forecasting and planning for potential cash outlays under certain structures (for example, portable alpha structures involving swaps);

- Proper identification of embedded leverage in structures that attain beta exposure via leveraged derivatives and invest “excess” cash in alpha exposure;

- The correlation and volatility of alpha—some alpha generators provide low levels of alpha with small standard deviations; others provide higher levels of alpha with higher standard deviations—when virtually all active managers produced negative alpha during the last half of 2008, the correlation of these, plus the negative alpha, caused differing degrees of pain in portable alpha implementations; and

- Proper identification of counterparty risk.

The preceding list is far from exhaustive, but in our opinion represents a sensible starting point to identify and tackle critical implementation issues in portable alpha, especially in a more unsettled investment environment than that experienced in the recent past.

The conclusion after the first decade of use? Successful implementation of portable alpha has been rare. For some investors, moving from the low volatility, flush liquidity, tight spreads, low risk premiums, and high confidence in the markets to the opposite environment that accompanied the credit crisis, was necessary to understand the leverage, credit, and cash-flow related issues discussed in this chapter. This has contributed in no small measure to defining the concept of portable alpha in a more robust and less simplistic way. It may be that, after observing the full life cycle of the initial implementations of portable alpha (birth, development, maturity, abandonment by some), we are now moving to a more dynamic approach, where portable alpha becomes a key tool in both strategic and tactical asset allocation.

NOTES

1. See Coates and Baumgartner.

2. See Pensions & Investments 2009.

REFERENCES

Coates, Jack, and M. Baumgartner. “Portable alpha: A Practitioner's guide, unraveling the hype behind the latest phenomenon.” Morgan Stanley Alternative Investment Partners [date not included in publication].

Pensions & Investments. 2009. “Plans Dump Portable Alpha as Returns Sour.”

Sharpe, William F. 1964. “Capital Asset Prices–A Theory of Market Equilibrium Under Conditions of Risk.” Journal of Finance 19:3, 425–442.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Tanya Beder is currently chairman of SBCC in New York and SBCC Group Inc. in Connecticut. SBCC, founded in 1987, has a broad base of hedge fund, private equity, traditional investment management, financial services, and corporate clients. From 2004 to 2006, Tanya was CEO of Tribeca Global Management LLC, Citigroup's $3 billion multi-strategy hedge fund, and from 1999 to 2004 was managing director of Caxton Associates LLC, a $10 billion investment management firm. Tanya sits on several boards of directors, including a major mutual fund complex and the National Board of Mathematics and their Applications. She has taught courses at Yale University's School of Management, Columbia University's Graduate School of Business and Financial Engineering, and the New York Institute of Finance. She has published in the Journal of Portfolio Management, Financial Analysts Journal, Harvard Business Review, and the Journal of Financial Engineering. She holds an MBA in finance from Harvard University and a BA in mathematics from Yale University.

Giovanni Beliossi is currently managing partner at London-based FGS Capital LLP, where he has been CEO and responsible for portfolio management since co-founding the firm in 2002. Previously he was associate director of hedge funds at First Quadrant Ltd, also in London. His experience of managing alternative investment portfolios dates back to 1995, when he joined the firm. Prior to that he was a tenured Research Fellow with the Economics Department of the University of Bologna in Italy, and he has held appointments with BARRA International and Eastern Group PLC. Giovanni is a Board and Research Committee member of Inquire UK and Inquire Europe, and a Board member of the International Association of Financial Engineers (IAFE). He is the European Chair of the Steering Group of the Investor Risk Committee (IRC) of IAFE working on guidelines for disclosure and transparency for hedge funds. Giovanni is a CFA Charterholder.

Tanya Beder and Giovanni Beliossi served as board members of the International Association of Financial Engineers (IAFE), and they co-chair the IAFE's Investor Risk Committee (www.iafe.org).