Chapter 29

Influencing Financial Innovation: The Management of Systemic Risks and the Role of the Public Sector

INTRODUCTION

This chapter discusses the limits to market-based risk transfer and risk mitigation instruments, and the implications for the management of systemic long-term risks. Instruments or markets to transfer and better manage such risks across institutions and sectors are, as yet, either nascent or nonexistent. As such, the chapter investigates why these markets remain incomplete. It also explores a range of options by which policy makers may encourage financial innovation and the development of markets as part of governments’ broader role as a risk manager.

We start by showing that, while financial markets have demonstrated significant innovation regarding the management of a variety of nontraditional risks, little activity is occurring with regard to some of the most significant longer-term risks. However, we show that some innovations may provide the building blocks for further advances in risk management instruments and markets. In addition, we discuss the important structural impediments to further growth in the size and scope of certain markets, including data availability, regulatory frameworks, rating agency treatment, tax and accounting policies, and market structure.

We next outline the principal long-term systemic risks, focusing on certain long-gestation, often-accumulating risks, which may have a potentially significant impact on national economies and financial markets. In particular, we evaluate pension savings and related challenges, including longevity risk, health-care costs and related liabilities, and house price risk (particularly as it relates to household retirement savings). We then explore why risk transfer activity is largely absent or, to date, ineffective in these areas. The chapter highlights the ability of public authorities to influence market development and risk management practices, which may encourage greater innovation in a variety of alternative risk transfer markets. Government policies may often help to improve the measurement of risks, and therefore the management and potential transfer of risks to institutions or persons better suited to manage particular risks.

Finally, the chapter makes a case for governments to act as a macro risk manager by taking a long-term, broad-based, and proactive approach to the management of such risks across sectors. Three complementary policy approaches are highlighted: (1) governments may use the many different policy levers at their disposal to encourage private-sector and market-based solutions to foster more complete markets; (2) governments may determine, in some cases, that the least costly or most efficient approach is to use their own balance sheets, acting as the insurer of last resort; and (3) governments may determine that households, as the ultimate shareholders of the system, are best positioned to manage these risks themselves.

By seeking at an early stage to influence private-sector initiatives and innovations to pursue policies designed to develop additional risk management tools, governments (and their various constituencies) may be better able to develop and evaluate public policy initiatives, as well as to better monitor and measure policy performance. In this sense, efforts to develop greater public- and private-sector market risk management activities may produce a virtuous circle.

FINANCIAL MARKET INNOVATION

Thus far, most financial innovations that help to identify, measure, and manage systemically important risks have been applied to more traditional insurance risks, such as peak mortality and natural catastrophe (CAT) risks. Although these innovative markets are small, they are expanding, and important lessons can be learned and applied to better measure and manage long-term systemic risks.

Many of the financial innovations recently developed to measure and manage credit risks are increasingly finding application in the insurance sector. Some of the recent innovations highlight features critical to the development of insurance-oriented risk management tools, including: (1) the capability to define, isolate, and measure risk exposures more precisely; (2) the ability to model and project the evolution of risk; (3) the ability to mitigate moral hazard in the reporting of risk events and data construction; (4) regulatory and rating agency recognition of risk mitigation strategies and techniques; and (5) the structuring of such risks to attract global investment capital and thus expand existing coverage and address new and emerging perils.

Many of these characteristics are evident in recently developed market-based risk management instruments that have been well received by market participants, as discussed later. Such instruments may be broadly divided into three groups, based on how the contingent payments are triggered by the occurrence of the covered risk.

- Parametric instruments base the contingent payments on objective data and modeling customized to, and correlated with, the underlying events related to the potential losses of the issuer or insured party.

- Contingent payments of index instruments are linked to more generic industry-wide and/or geographic indices that are (more broadly) correlated with the events triggering the covered risks. They are simpler to execute than parametric instruments, although both expose ceders (e.g., reinsured parties) to basis risk (i.e., the risk that the insurance coverage does not exactly match actual losses).

- By contrast, indemnity instruments base the contingent payments on the issuer's actual loss experience, which makes them a close substitute for a reinsurance contract.

The use of parametric and index products is growing rapidly. These instruments, while presenting certain basis risks, allow payments to be made quickly to the insured party after a loss has occurred, and tend to attract a wider and diverse investor capital base.

Application of Recent Innovations to Insurance Risk Management

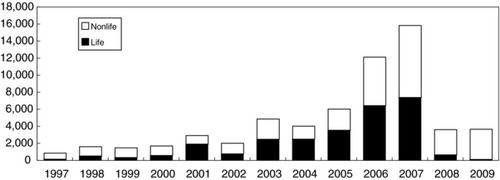

Life insurance securitizations are often based on standardized and well-defined actuarial risk measurements, which should allow for better understanding and modeling of life risk, similar in some respects to mortgage securitizations and auto insurance risk. Life insurance securitization increased from near zero in 1997 to about $7 billion in 2007.1 During the same period, non–life insurance securitization increased from about $1 billion to about $9 billion. These transactions have been spread among approximately 20 insurance and reinsurance firms, and primarily relate to natural catastrophe risks, although some of the transactions also involve auto and industrial accident insurance. (See Exhibit 29.1.)

Issuance volumes in both sectors have fallen off sharply since 2007. Life insurance securitization volumes have declined largely due to a lack of investor appetite for transactions wrapped with monoline insurer guarantees (see later discussion). Non-life insurance securitization fell off in early 2008, on account of a surplus of traditional reinsurance capacity, and dried up completely after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. A number of CAT risk bonds were backed by poor-quality collateral supposedly protected by credit derivative contracts with Lehman.2 When these bonds were sharply downgraded, investors stepped back on fears that other CAT bonds were similarly exposed to credit risk. However, these markets restarted in February 2009, as issuers introduced more conservative collateralization procedures and reinsurance markets tightened. Volumes have since bounced back smartly, although not to the 2007 peak volume levels. But even at those peak activity levels, the amount of insurance-related risk transfer activity represented only a small fraction of the potential underlying exposure.3

The securitization of peak mortality exposures, primarily related to pandemic-type risks and relying on parametric triggers, has illustrated the importance of identifying and measuring precisely the specific risk, including the use, where possible, of an index constructed by an independent agent.4 The index is based on mortality rates in populations to which the insurer is exposed, and payouts from the bond are triggered upon breaches of prespecified levels. Indeed, the development of robust indices may be a key factor in the growth of insurance securitizations or related capital market insurance products, as well as related risk management tools.

A significant motivation for insurance companies to transfer risk concerns economic and regulatory capital considerations. For instance, a large volume of securitizations by U.S. life insurers has been motivated by Regulation XXX, which became effective in 2000. This regulation requires insurers to set aside statutory reserves against term life insurance policies that are generally viewed as higher than economically warranted by current actuarial experience and data. By shifting some of their risk to capital markets, such securitizations allow insurers to hold fewer reserves than required by Regulation XXX.5 According to Goldman Sachs, of the $27 billion in life insurance–linked bonds issued globally since 1997, $13 billion were motivated purely by Regulation XXX and capital management objectives. However, Regulation XXX securitizations depend on monoline wraps to achieve the AAA ratings that investors expect, so with the monoline insurers facing their own financial challenges, the primary market has effectively been closed since 2007. Liquidity and funding considerations have also been a driver of so-called embedded value insurance securitizations, of which about $13 billion have been issued since 1997. The primary purpose of these indemnity-type transactions is to monetize expected future profits (the embedded value) on blocks of life insurance policies, since the associated expenses and regulatory reserves tend to be front-loaded, whereas the profits accrue over the life of the policy.6

Non-life exposures (e.g., natural catastrophes) are considered more difficult to precisely measure and model, and the amount of natural CAT risk sold in the capital markets to date has been a small fraction of the total amount of insured CAT exposure.7 Nevertheless, the growth of CAT bonds and risks covered shows how innovation is often very dependent on data and modeling developments, in order to assess risks with the required level of confidence. Although both parametric and indemnity-type instruments are used to cover or transfer such risks, insured parties and investors increasingly prefer parametric issues, while regulators prefer indemnity instruments.

Natural CAT and peak mortality bond transactions are now applying structuring techniques typically seen in credit markets. For example, the $300 million Bay Haven transaction launched in 2006 was structured very much like a traditional collateralized debt obligation (CDO), in that it is comprised of multiple tranches that expose investors to a graduated variety of insurance risks (e.g., a relatively high-risk, first-loss or equity tranche, up to a much lower-risk senior tranche that absorbs only the most remote referenced losses). The $310 million Gamut Re “collateralized risk obligation,” launched in 2007 involved an actively managed pool of underlying natural CAT risks, and the $200 million Freemantle and $1,138 million Merna transactions both included AAA-rated tranches. Some peak mortality bond issues have included tranches that are wrapped with monoline insurer guarantees so that they could be rated AAA by Moody's Investors Service and Standard & Poor's (S&P). But those without wraps have been rated no higher than AA–, with most being rated from BBB to A–. The investor base for CAT bonds has previously comprised specialized hedge funds and reinsurers, so it is notable that the senior tranches of these CDO-like transactions have attracted life insurers and other money managers.8

Natural CAT risks are also being transferred via CAT swaps and industry loss warranties (ILWs)—both relatively new instruments. CAT swaps have typically involved two reinsurers seeking diversification benefits (i.e., by type and/or location of peril—for example, Japanese earthquake for European windstorm risks). More recently, hedge funds and other institutional investors are showing interest in these markets. Hedge funds are also involved in the market for ILWs, which are reinsurance contracts that incorporate derivative-like features.9

Hedge funds have also formed reinsurance companies during periods of rising premiums, and are increasingly supporting primary insurance market activity. For example, from 2005 to the end of June 2009, in Bermuda, hedge funds and private equity firms raised about $24 billion of new reinsurance capital, including about $9 billion structured as sidecars.10 A sidecar is a limited-purpose reinsurance vehicle with a finite life, typically established to do business with a single reinsurance client and/or to underwrite a particular risk.11 Such activity has dropped off since 2007, as premiums have fallen from the record highs of 2006, and credit rating agencies have tightened their criteria for reinsurance start-ups.

Private-Sector Innovations for Managing Slow-Burn Risks

Encouraged by the increased public debate regarding pensions funding in the United Kingdom, investor interest has grown, and financial market initiatives have been launched to transfer pension-related risks. For example, private equity–style funds (buyout funds) have been established in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, seeking to acquire the assets and liabilities of closed defined-benefit pension plans, including their exposure to longevity risk. Along with a few existing insurance companies, such funds seek to purchase and subsequently manage this risk in the financial and reinsurance markets, which may stimulate further market innovation.

Broader investor interest in markets for long-term systemic risks will likely require better and timelier data to provide greater certainty of pricing and payment.12 In addition, index design may play an important role, such as the U.S. house price index futures that began trading on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) in 2006. The CME is trading contracts for 10 U.S. metropolitan areas, and settlement is based on the values of corresponding S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices, which are published monthly.13 For health-care costs, the Milliman Medical Index, first published in 2006, focuses on medical costs based on employer-sponsored managed-care accounts in the United States.14 This index, which is available for 14 major metropolitan areas, reflects actual medical care expenditures (not insurance premiums), and is designed to track employee medical spending on a yearly basis. However, the infrequent updating of the Milliman index (i.e., annually) may hamper its ability to serve as an effective hedging tool for health-care providers and insurers. Nevertheless, these are important financial market developments, which provide a greater ability to measure and potentially to manage a number of important economic risks.15

As discussed in the following pages, key challenges to expanding nontraditional risk management tools include regulatory and supervisory frameworks, as well as rating agency expertise, and support for recent and continuing financial innovations. For these and other reasons (e.g., investor knowledge, accounting treatment, and market structure), markets to better manage a variety of important risks remain incomplete.

Application of Recent Innovations to Public-Sector Risk Management

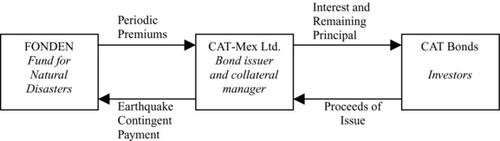

Public-sector use of risk management tools and risk transfer markets has not been significant thus far, with only a few sovereigns looking to insure or otherwise hedge various risks, including in the capital markets and the issuance of CAT bonds. However, in 2006 Mexico issued a CAT bond covering earthquake risk, and agricultural and livestock insurance is becoming more widely available (Boxes 1 and 2). Such transactions highlight the growing attraction of insurance and hedging instruments, including contingent-capital–type instruments. Increasingly, these public-sector transactions include parametric and index features, providing greater certainty regarding trigger events, and faster payments to the insured parties.

Box 1: Mexican Earthquake CAT Bond

In May 2006, Fondo de Desastres Naturales (FONDEN), a Mexican government agency created to provide emergency relief for natural disasters, issued a $160 million parametric CAT bond to reduce the potential fiscal impact of an earthquake of similar or greater magnitude to the one that killed 10,000 people in 1985 (i.e., 7.5 or more on the Richter scale).1 The bonds were part of a $450 million three-year insurance transaction.

The rationale for a sovereign to issue CAT bonds includes diversification of insurance coverage, which often improves the coverage and pricing of the overall insured peril. CAT coverage may be particularly relevant for middle-income countries, for whom self-insurance may be less of an option and where coverage is seen as affordable, relatively efficient (i.e., in scope of coverage and timeliness of payment), and complementary to traditional relief or donor funds. (See Exhibit 29.2.)

Exhibit 29.2 Mexican CAT Bond Structure

The bonds were rated by Standard & Poor’s, and investors receive a floating-rate coupon. Should there be an earthquake that meets the trigger criteria, FONDEN immediately receives the full principal amount from CAT-Mex Ltd., and the bonds are canceled. In October 2009, FONDEN followed up with a similar $290 million “MultiCat” bond that covered both earthquake and hurricane risk.2

1 More specifically, the payout is triggered by a 7.5 magnitude earthquake in and around Mexico City and/or an 8.0 magnitude earthquake in one of two Pacific Coast areas.

2 The “MultiCat” issuance platform was developed by the World Bank to offer a standardized product to member countries that uses a common legal structure and documentation, while being flexible in terms of types of risks covered.

Box 2: Financial Innovations Supporting Humanitarian Aid

A large number of natural catastrophes occur in emerging-market and low-income countries, with international agencies and charities typically covering most of the costs of recovery and reconstruction. CAT-like financial instruments may provide an additional source of capital to support such traditional assistance.

For example, in March 2006, the United Nations World Food Program (WFP) insured Ethiopian drought risk (covering the period from March to October 2006) via a derivative transaction with a French insurer.1 The WFP contracted for the insurer to pay specified amounts if a predefined Ethiopian drought index rose above an agreed trigger point. Whereas conventional aid can take many months to arrive and insurance settlements usually occur only after a lengthy verification and loss-adjustment process, this transaction structure delivers the contingent payment within weeks of the trigger being breached.

The World Bank, which was involved in the Ethiopian transaction, has also developed a pilot project to provide Mongolian livestock herders with index-based peak livestock (cattle and yak) mortality protection. It features a tranched structure, whereby commercial insurers will cover losses for mortality rates between 7 and 25 or 30 percent per species, and the Mongolian government will cover losses in excess of 30 percent. Herders pay premiums for the 7 to 30 percent protection, based on the value of their herds, which will encourage risk mitigation efforts.2

Projects like these serve as important starting points and initiatives for the development of market-based insurance solutions for developing countries and the coverage of a potentially wider variety of risks or perils.

1See Syroka (2006). A similar program has been in operation in India since 2003 (see World Bank 2005).

2See Mahul and Skees (2006).

There are several significant economic risks facing industrial countries (and many developing economies) in the medium to long term, which have the potential to produce severe economic costs and possibly financial instability. Given their systemic importance, such events can have material GDP, real economy, and welfare impacts. Some of the most significant risks relate to global demographic trends and aging populations, such as pension and health care provision, which are expected to put tremendous pressure on public and private finances in the medium term, causing some countries to rethink the role and scope of the welfare state. An additional, and somewhat related factor, is that many countries have to rethink or develop energy and even food strategies, in light of tighter supply-demand dynamics in these important commodity markets. Moreover, in each case, the potential adverse economic and financial stability impacts of these developing risks are likely to be more significant the longer policy makers delay actions designed to mitigate or to better manage such risks and related effects.

G-10 policy makers recognize that these longer-term risks present major challenges to public and private finances during upcoming decades. However, a number of countries have indicated that necessary reforms to entitlement systems, subsidies, tariffs, and other policy constraints possibly needed to address these challenges are politically difficult to implement, and may be delayed or lead to undesirable compromises. Of course, markets dislike uncertainty, and these growing long-term risks will serve only to increase market uncertainty. Moreover, the financial crisis of 2007–2009 has only served to further stretch government balance sheets and intensify fiscal pressures. Therefore, at some point, possibly before government actions are taken, as the financial markets act to more clearly measure and anticipate the economic effects of these challenges, the resulting impact and subsequent adjustments could be disorderly.16

Governments have a variety of options, including tax increases and benefits reductions, particularly when addressing risks such as health care and pensions. In some countries, the public sector has assumed many of these longer-term risks, yet current government accounting standards often do not require the quantification, reporting, or funding of such future obligations.17 Consequently, finance ministries frequently do not face a binding requirement, or have strong incentives, to proactively manage growing pension or health-care exposures. Going forward, government accountability for longer-term risk management may require improved public accounting and reporting standards, more robust fiscal frameworks, explicit estimates of contingent liabilities, and increased portfolio risk management by finance ministries. Until that happens, public-sector use of capital market-based risk transfer tools may remain limited.

Other Recent Innovative Risk Transfer Activity

The financial crisis of 2007–2009 has dampened innovation in a number of additional areas of risk transfer while highlighting its potential benefits. For instance, pure macroeconomic risk transfer mechanisms (e.g., GDP futures and swaps) are only intermittently transacted on a bilateral basis. However, the crisis has accelerated the development and trading of sovereign credit default swaps (CDS), which tend to be transacted more as a macro hedge against exposure to a country or a banking system rather than as protection purely against a credit event applying to the sovereign borrower. For instance, observers point out that buying credit protection on the U.S. government is a somewhat bizarre concept since, in the event of default by the United States, there is little likelihood that the counterparty selling protection (or the collateral) would be in existence to meet the obligation. However, this ignores the macro hedging use to which sovereign CDS are put to provide protection against sovereign downgrades or banking sector collapse.

In another area, the policy thrust toward cap-and-trade mechanisms to curb carbon emissions, the trading of CO2 emissions permits and futures, is now an important element in the efficient pricing and distribution of the burden of emissions reduction. Such futures contracts are actively traded on bespoke exchanges and brokered markets where cap-and-trade schemes are operational (notably within the European Union, with some trading occurring in some states within the United States). However, the liquidity and robustness of such markets depend heavily on the reliability of the policy-making framework for permit supply and allocation, as well as careful design features within the schemes (e.g., bankability of permits between allocation periods). Policy errors in these areas in the recent past in the EU scheme have hampered the market's development.18

INCOMPLETE MARKETS FOR INSURANCE RISK

This section focuses on the potential reasons why capital market–based solutions for managing insurance risks may remain relatively undeveloped compared, for instance, to those used by banks to manage credit risk. Some reasons may reflect the fundamental nature and characteristics of particular risks, as well as their degree of insurability or transferability (see Box 3). Others may reflect institutional momentum, in that, historically, insurance companies have often warehoused many of the risks discussed in this chapter, rather than seeking (or being encouraged) to more proactively manage such risks.

The following are some of the key influences on market behavior, risk management practices, and financial innovation: (1) regulation and supervision, (2) rating agencies, (3) accounting and tax policies, (4) market structure, (5) data availability and quality, and (6) risk-sharing arrangements.19 This section focuses on how these influences may explain why certain markets remain incomplete, and suggest potential public policy responses in order to complete certain incomplete markets.

Regulatory Influences

The Basel regulatory framework created incentives for banks to increasingly focus on risk measurement and management. Policy makers in industrial countries, as expressed in Basel regulatory principles, determined that banks should be encouraged through risk-based capital guidelines to better measure and more actively manage different credit and balance sheet risks, and thereby increase the resilience of their balance sheets for a given level of capital. This led to significant capital market innovations, including increased risk transfer. In short, the Basel framework spurred the development of more active and innovative risk management practices.

Similar regulatory influences on insurance companies’ risk management practices have generally not been forthcoming. Indeed, insurance regulators have often been ambiguous, or even ambivalent, as to whether insurers should seek additional methods to manage and transfer their insurance risks via the capital markets rather than remaining the ultimate holders of such risk (i.e., warehousers of risk). Traditionally, insurance regulation has focused primarily on consumer protection and often-prescriptive rules related to asset portfolio management, rather than on more macro prudential and financial stability considerations, or related efforts to improve risk management practices. Consequently, insurance supervisors may often assume that insurers act (or should act) as risk repositories or warehousers of risk, and, therefore, that dedicated reserves are required to ring-fence each of the distinct risks that insurers underwrite. Moreover, reserves are often ring-fenced with their underwritten risks, and rarely viewed by some supervisors as the economic equivalent of capital, to be managed and available to address a variety of risk exposures. Based on this view of insurance regulation, reserve requirements typically are not adjusted if risk is actively managed, transferred, or hedged via the capital markets. Likewise, traditional reinsurance arrangements typically attract reserve relief only if the risk is transferred in its entirety (e.g., on an indemnity basis), which usually requires dedicated reserves from the reinsurer to be held in the covered jurisdiction (often referred to within the industry as “trapped” capital).

Of course, it can be, and has been, argued that such regulatory capital regimes are more stable and safe than the more dynamic or market risk management approaches. We understand that argument, but believe that this traditional regulatory approach seems less likely to attract new capital or encourage better risk management practices. In our judgment, both more capital and better risk management and measurement practices are needed on a systemwide or marketwide basis if we are to effectively address some of the long-term and accumulating risks in the global economy. In fact, in some markets (e.g., retail-oriented coverage) insurance capital and capacity have been reduced in recent years, due in part to political interference in the pricing and/or scope of coverage (e.g., Florida property and casualty), as well as considerations related to trapped capital. While remaining focused on macro prudential and consumer regulatory protection, policy makers need to attract more capital, not less, to a variety of broadly defined insurance risks.

Box 3: What Makes a Risk Insurable, and Possibly Transferable or Tradable?

The degree of insurability of various risks, and thus the manner which they may be managed or possibly transferred, depends on a number of considerations. In general, insurability is enhanced when a risk is assessable in terms of both its frequency and its severity, when insured events are independent of one another and losses relatively uncorrelated, and when risks may be mitigated by seeking diversification benefits through pooling or other means. In addition, transferring risks in the financial markets depends on the ability to identify, measure, and isolate specific risk characteristics, ideally using independent assessments (e.g., by rating agencies or specialized risk modeling firms).

Perceptions about the types of risk that can be intermediated change over time due to financial innovation. Moreover, such innovations are very often influenced by regulatory frameworks and technological advances, particularly with regard to the ability to better measure and decompose complex risk exposures.

Financial innovation acts to expand the boundaries of risk insurability and transferability, as most clearly illustrated by the management of credit and interest rate risks. Advances in financial market techniques allow risks that were previously considered uninsurable to be more precisely measured and proactively managed, and thus made insurable. One method by which insurers approach these issues and classify risks is by considering whether a risk exposure reflects a one-sided or a two-sided market. The latter typically involves counterparties with offsetting initial exposures (e.g., currency risks) who clearly benefit from trade. As such, two-sided risks are considered most amenable to market-based risk management activity. By contrast, one-sided risks affect exposed parties in broadly similar ways (e.g., natural catastrophes and longevity), and far fewer, if any, natural counterparties exist. Therefore, managing one-sided risks has traditionally involved pooling by (re)insurers, and charging a premium to warehouse such risks for a period of time. In addition, and very importantly, (re)insurers often also rely on the ability to periodically reprice insured risks (usually annually), which helps to adjust or limit their exposure and results in insurance customers sharing in the costs of an increase in insurance losses.

Interestingly, some risks, previously perceived as one-sided, may become more two-sided, and thereafter may be transferred to a broader group of investors as new technologies and financial instruments are developed. By creating a market price for these risks, such innovations enable insurers and other market participants to more accurately measure and manage their exposures, thereby further increasing the likelihood of one-sided risks becoming tradable.

In the absence of a clear approach or regulatory framework regarding the role of insurers, only a few of the largest and most innovative insurance companies have pursued market-based risk management techniques. These insurers have been motivated in part by economic capital, capacity, and broader balance sheet and return objectives. Insurance companies can face significant difficulty in obtaining regulatory capital relief for such activities.1 For example, while U.S. insurers can deduct the cost of reinsurance from their gross premiums for the purpose of calculating risk-based capital requirements, they generally cannot do so when securitizing risks transferred in the capital markets. In some cases, supervisors cite concerns about residual basis risk from capital market transactions (e.g., which may exist with nonindemnity structures, as noted earlier) that are not considered present with typical reinsurance arrangements. Consequently, risk reduction methods with payoffs based on indemnity triggers are more likely to be granted full capital relief, whereas the regulatory treatment of structures with payoffs based on indices or parametric triggers is typically less certain and less favorable. Relative to bank regulatory treatment, insurers in most countries get little or no regulatory credit for partial hedges or dynamic hedging strategies (e.g., transactions with term mismatches), a factor that acts to discourage proactive risk management strategies in the insurance area.

1For example, whether regulatory capital relief or benefit was given for the Fonds Commun de Créances (FCC SPARC), a French auto securitization transaction remains unclear to outside observers (see IMF 2006, Box 2.3). However, it is broadly assumed that the insurer received no regulatory capital benefit.

However, a number of insurance regulators have started to develop more comprehensive risk-based capital requirements, which recognize the benefits of reinsurance, securitization, and diversification within the risk portfolio. For example, Switzerland implemented a principles-based supervisory framework, seeking to promote a greater focus on risk and capital management and to provide insurers with regulatory capital relief for market securitizations.20 In the Netherlands, the authorities have strengthened the regulation of pensions, particularly through more risk-based supervision, which encourages pension fund managers to focus more on risk management and asset-liability management. The U.K. Financial Services Authority also signaled its willingness to promote insurance risk transfer markets through insurance special purpose vehicles, thereby building on its new risk- and principles-based approach to insurers’ capital adequacy.21 In Asia, some regulators (e.g., the Monetary Authority of Singapore) have also encouraged more proactive risk management practices in the insurance industry.22

A risk-based approach is also encompassed in the EU's Solvency II framework, and in the parallel work being conducted by the International Association of Insurance Supervisors. Solvency II is a major initiative to strengthen risk management practices in the European insurance industry. By promoting greater capital management discipline, it should enable EU regulators to better align regulatory capital requirements with economic capital models.

Despite these initiatives, some market participants express doubts regarding the potential for significant cross-border regulatory coordination in the insurance sector. They see the traditional consumer-protection versus risk-based approaches, as outlined earlier, as difficult to reconcile and unlikely to lead to more common or coordinated international standards.23 Therefore, the impact of Solvency II and related efforts remains difficult to predict.24

Rating Agency Clarity

Like regulators, rating agencies have not been viewed as a driving force in promoting or supporting the use of market-based risk management tools by insurers. Once again, in contrast to the credit markets, where rating agencies have had a material influence on credit risk analysis and management, the agencies have not thus far displayed the leadership or expertise needed to support the development of market-based risk management tools in the insurance area. In addition, and similar to the regulators, their recognition of any risk mitigation benefit to an insurer generally depends on the structure of risk transfer mechanism used. Consequently, reinsurance arrangements (i.e., indemnity policies) are typically recognized (although some allowance may be given for counterparty risk), whereas in contrast, no (or only partial) relief may be granted for parametric and indexed structures (favored by the insured parties and capital market investors for their clarity), due to the potential basis risk.

In light of the criticism and increased scrutiny and regulation that rating agencies are likely to encounter going forward, they may not act in the near term to further recognize or look to expand the credit given to insurers for risk transfer activity. However, the major rating agencies have been revising their rating methodologies for insurance risks, including the use of insurers’ in-house capital and risk management models, and, together with the larger insurers, may contribute to the development of insurance-risk indices.25 Such developments may provide insurers with greater incentives to consider market-based risk management practices, and may attract a broader group of market participants and additional capital to the insurance market and new types of risks.

Accounting Policies

Under current accounting rules, transactions with the same economic effect or result are not always treated the same, which may hinder the use of market-based risk management techniques by insurers. Also, current hedge accounting standards can produce disincentives for insurers to use market-based risk management instruments, especially compared with the treatment given to reinsurance contracts. Indeed, current standards may not recognize any of the economic benefits from less-than-perfect hedges (e.g., index-based instruments), and may act to increase reported earnings and balance sheet volatility. Yet such higher volatility may be inconsistent with the underlying economic reality. Rating agencies have also suggested that hedge (and regulatory) accounting standards have dissuaded them from providing a clear ratings benefit to market-based risk management techniques compared with reinsurance coverage, as financial reporting volatility may produce increased market volatility for a company's securities.

More broadly, while the shift to fair-value accounting principles in many jurisdictions may bring more focus to insurance and pension fund financial reporting, it is not clear that the volatility associated with fair-value accounting measures properly focuses insurance companies or pension funds on effective risk management objectives.26 Therefore, policy makers may also consider whether broader disclosure of the asset and liability structures (including the maturity profile of liabilities, and market and interest rate sensitivities) may provide investors and beneficiaries with more useful information.

Market Structure

It has also been suggested that shareholder pressure to maximize returns on capital in the insurance industry may be relatively less significant than that in the banking sector, which may contribute to making risk transfer activity less urgent in the insurance industry. In addition, in some jurisdictions the prevalence of mutual insurers may act to reduce returns on capital.27 Market participants also highlight the relative ease with which (non-life) reinsurers are able to raise capital, especially following a large catastrophe, when premiums are expected to rise. Consequently, industry participants and observers state repeatedly that the industry is not capital constrained.

On the demand side of the equation, the absence of well-established benchmarks or indices and rating agency guidance, as well as a general lack of familiarity with insurance-type risks, have made it difficult to develop a broad and diverse investor base for many insurance-type risks, despite potential portfolio diversification benefits. To date, much of the investor demand has come from other insurers and similar specialists already familiar with such risks. Similar to developments in other markets, the diversification and dispersion of risk created, even within this specialist market, would likely enhance financial stability. Moreover, improved primary market liquidity for more risks may trigger a virtuous circle, whereby the availability of liquid market indices may emerge and attract new, diverse sources of capital.

Finally, ongoing consolidation among (re)insurers may eventually limit their ability to increase capacity through traditional risk management practices, such as portfolio risk pooling or warehousing risk, and may lead to increased market-based efforts to disperse risk and attract new capital.28 Moreover, the systemic importance of these institutions is likely to increase as fewer and fewer insurers play increasingly significant roles related to certain risks, such as retirement and health-care needs. This trend may, in turn, lead authorities to reconsider prudential regulation of insurers, and possibly encourage risk transfer beyond the insurance industry to reduce risk concentrations or systemic exposure to any one company or group of companies, and to attract more capital to a variety of additional risks.

Going forward, there is significant potential for a broader capital and investor base (and related risk management capacity) in the insurance industry, together with a more return-oriented approach to capital utilization. The recently increased presence of investors, such as private equity and hedge funds, including shareholders and owners of (re)insurers, may reflect the beginning of such a change.

Data Availability

Reliable data are critical for the development of market-based risk management solutions. Indeed, market participants often cite the inadequate availability, reliability, granularity, and timeliness of data as reasons for the absence or slow development of markets to manage longevity, health-care costs, and other risks. Data are needed to support the pricing and trading of risks, the development of risk models, and the construction of benchmarks or indices. Although the underlying data typically exist (e.g., hospital records, death statistics), they are often not systematically compiled or widely disseminated on a timely basis.

Long-term risks, such as retirement and health-care costs, are often difficult to measure because the underlying drivers of these costs may be inherently unpredictable, and because forecasts and related risk assessments may be possible only infrequently and with long time lags. For example, market participants emphasize that the pricing of annuity products is materially constrained by the lack of high-quality data on mortality for higher age categories (e.g., 85 to 90+ years), or beyond a 15- to 20-year period for most annuitants (i.e., typically aged 60 to 70 years). Consequently, the absence of adequate data increases the uncertainty associated with extreme longevity risk, resulting in higher capital requirements. Market participants have stated that approximately 20 to 25 percent of the value at risk of annuities sold to 65-year-old men in the United Kingdom relates to their potential to live beyond 90 years (see also Box 4).

For each type of risk, increasing data availability should create opportunities for better risk management. For example, to develop relevant and useful house price index contracts, the underlying data need to reflect local market conditions, and to support market liquidity such data should be published or updated on a relatively frequent basis. In this regard, although underlying house price data is published monthly, the low turnover and liquidity of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange house price futures contracts have proved disappointing. Another example is the health care sector, where the lack of data aggravates the fragmented and local nature of the delivery system (e.g., a variety of specialized health-care providers and insurers’ nonstandardized systems).29 These factors make it difficult to compile comparable health-care data on a broad basis, and thus deter the development of market-based risk measures and risk management tools.

Governments may have a comparative advantage and interest in improving the availability, reliability, and timeliness of certain data necessary for the development of markets to better manage various risks. Indeed, data provision may be a relatively low-cost method of supporting market-based solutions. For example, weather data are now relatively easy to collect cost-effectively and reliably, and can be used to facilitate the provision of agricultural insurance in middle- and low-income countries. Nevertheless, market participants cite the absence of comparable health-care data, the unreliability and out-of-date nature of mortality information, and the lack of reliable local data on house price movements as reasons risk management tools have been slow to develop, or are altogether absent from financial market analysis.30 Such government initiatives may only need to be temporary, until a growing market demand leads to data collection and dissemination by the private sector.

The U.K. commercial property index derivatives market provides an example of the importance of the combination of regulatory, tax, and data considerations. The development of this market has been based on: (1) the existence of reliable and comprehensive commercial property indices, on which contracts-for-difference and swaps are based; (2) a ruling by the U.K. Financial Services Authority (FSA) in November 2002 that allowed property derivatives to qualify as admissible assets for life insurers, thereby counting toward their regulatory solvency ratios (in addition, the ability to hedge underlying positions in a property index enables insurers to save capital in the FSA's risk-based capital regime); and (3) a tax change in September 2004 that gave property derivatives the same treatment as other derivatives. As a result, transactions have grown significantly since early 2005 and exceeded £8 billion in 2007.31

Box 4: Annuity Obligations and Longevity Risk

Annuities provide individuals with the opportunity to hedge longevity risk—the risk of outliving one's assets. In its simplest form, a life annuity provides a guaranteed income flow throughout the annuitant's lifetime, thereby hedging the individual's longevity exposure.1 However, annuity providers face the challenge of hedging the aggregate longevity risk associated with annuitant cohorts, because a number of exogenous factors (e.g., medical advances) result in the relatively high correlation of the longevity of cohort members.

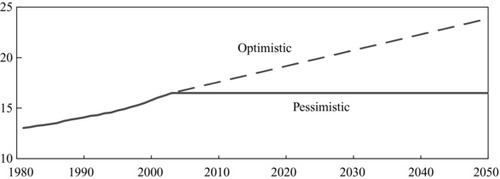

The contracted rate of return to the recipient of an individual annuity consists of a market return plus a mortality credit from pooling. This mortality credit is a source of risk for the annuity provider that cannot be easily hedged. For example, in a fixed-income annuity pool of 65-year-old males, in which about 2 percent would be expected not to survive the first year, pooling provides a one-year mortality credit of about 214 basis points if the rate of return is 5 percent.2 The value of this credit rises with the age of the pool of annuitants. For example, it reaches about 1,853 basis points for a group of 90-year-old males, of whom 15 percent would not be expected to survive a year. However, if the actual 90-year-old male mortality rate were only 14 percent, the available funds to pay the mortality credit would be reduced by 144 basis points, and the annuity provider would have to make up the difference. Indeed, projections of cohort mortality have typically understated future life expectancy and, as illustrated in Exhibit 29.3, there is a great deal of uncertainty about future longevity trends.3 Given that the increase in longevity, as well as the uncertainty of projections, affects all annuitants in broadly equivalent ways, it is largely nondiversifiable, and results in relatively more capital being required to cover the annuity providers’ risk exposure to extreme longevity.4

Exhibit 29.3 U.K. Male Cohort Life Expectancy at Age 65: Optimistic versus Pessimistic Projections

Sources: U.K. Government Actuary's Department; International Monetary Fund staff estimates.

One way to hedge longevity risk may be to transfer some of the exposure to investors via so-called longevity bonds or swaps.5 However, it is difficult to find potential counterparties to such transactions who themselves are not already exposed to longevity risk (i.e., a potential one-sided market). Also, the need for long-dated longevity hedging instruments increases concerns about counterparty credit risks. Nevertheless, since January 2008 $2.6 billion of longevity swaps have been completed by pension funds in the United Kingdom.6 Prior to the successful completion of these transactions, governments were frequently viewed as attractive counterparties, notwithstanding that most governments already have large exposures to longevity risk through their public pension and social security commitments. However, the unsuccessful attempt by the AAA-rated European Investment Bank (EIB) to launch a longevity bond in 2004–2005 illustrates how difficult it is to design such market-based longevity risk transfer instruments.7

1See Poterba (1997) for descriptions of the many variations on standard annuities, and Milevsky (2006) for the mathematics behind many of the concepts discussed here.

2The example assumes away survivor benefits, which would reduce the mortality credit. The one-year mortality credit is equal to R * [M/(1 – M)], where R is the gross rate of return and M is the mortality rate. See Milevsky (2006) for more detail.

3See Watson Wyatt (2005) for a discussion of the drivers of the optimistic and pessimistic longevity projections.

4The life insurance business is occasionally viewed as providing some natural hedging opportunities (Cox and Lin 2005), but these are typically significantly less than some assume. Indeed, such hedging opportunities are typically quite limited due to cohort mismatches—the age profile of a typical annuity pool cohort is much older (e.g., 55+ years) than that of a life insurance portfolio, which tends to reflect events earlier in an insured's life, such as marriage and having children (Brown and Orszag 2006).

5See Blake and Burrows (2001), Dowd et al. (2005), and Lin and Cox (2005).

6According to Aon Benfield (2009), legislative changes and new accounting rules are pushing U.K. pension funds to seek longevity risk mitigation solutions. Also, the legal and regulatory landscapes make longevity risk transfer more feasible.

7The failure of the EIB longevity bond has been attributed to several design flaws, including a somewhat narrowly defined underlying index (based on 65-year-old English and Welsh males) and (more importantly) its 25-year maturity, which left extreme longevity (i.e., above 90 years) uncovered (Blake et al. 2006).

PUBLIC POLICY CONSIDERATIONS

Through the use of various policy levers, governments influence the flow of risks in the financial system, and can encourage the development of new products and risk management tools, contributing to financial stability in the process. This occurred in the credit markets throughout the 1990s. Many observers believed previously that credit risk was inherently untransferable or untradable, which has proven not to be the case. Similarly, today many insurers and other market participants believe that certain of the risks highlighted in this chapter reflect one-sided risks or markets, and therefore may be appropriate only for traditional insurance risk management practices, such as portfolio diversification and pooling. However, governments may influence these markets and risk management practices. Some of the policy tools available to the authorities to encourage market innovation and alternative risk management activities have already been discussed (regulatory and supervisory frameworks, accounting standards, and data availability), and others include tax policy and compulsion. Moreover, as a practical matter, and in light of current and growing fiscal pressures on government finances, policy makers should explore means to attract more private capital to address these long-term risks and societal challenges.

Tax Policy

The structure of taxation can also significantly influence the development of risk management practices. First, governments need to consider whether existing tax systems may inadvertently penalize (and possibly prevent) the transfer of risk to other market participants.32 For example, capital losses on derivative instruments and the costs of securitization should be taxed similarly for insurers to ensure neutrality of treatment between market risk transfer, reinsurance, and retaining risk on balance sheet.

In addition, tax incentives may be considered in some cases, even if temporarily, to encourage desired risk management practices. For instance, tax regimes for company pension funds should be designed to encourage prudent, possibly continuous funding policies, and to ideally incentivize companies to build reasonable funding cushions (e.g., two or three years of normal contributions).33 With regard to the household sector, the clarity and stability of tax regimes are deemed essential to encourage the development of adequate long-term savings and investment products. More broadly, tax incentives may also be considered to facilitate the development of new markets, such as macro swaps, through which (for example) the pension fund and health-care industries could swap their complementary cash flows and exposure to longevity. Longevity increases lead to both greater liabilities for pension funds and higher revenues for health-care companies (from increased health-care spending by the elderly). The availability of an index reflecting the cumulative survival rate in a given population would provide the basis for both parties to trade their symmetric exposures, and to hedge against unexpected changes in longevity. Governments may encourage these transactions (for example) by introducing appropriate tax incentives for the health-care industry, perhaps conditioned on certain research or product development efforts targeting the needs of an aging population.

Compulsion

The need to pool diversified risks is an important feature of insurance, including annuities and health-care coverage. To help reduce adverse selection and bias, governments may require that a minimum degree of insurance be purchased by all persons. Such an option also helps to limit the potential costs that may ultimately be transferred to the public sector. With regard to longevity risk management, mandatory annuitization (similar to more specific risk measurement) may encourage the emergence of simpler annuity products, and potentially improve households’ understanding and acceptance of such products. In the health-care sector, many Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries have mandatory universal public or private health care, which may be a way for the government to overcome market limitations. For example, in 2006, the Netherlands introduced compulsory private health-care insurance, under which private insurers are required to accept any Dutch citizen for basic health-care coverage, regardless of the person's health condition or age.

CONCLUSION

Financial markets may play a greater role in the management of longer-term systemic risks. Governments should seek to encourage and positively influence market developments in these areas with the goal of completing incomplete markets. A clear and consistent regulatory framework can encourage innovation in risk management techniques. In some cases, governments may need to intervene directly in certain markets, perhaps temporarily, to provide some minimum and/or extreme insurance coverage, ideally to facilitate the development of private capacity.

The preceding discussion has highlighted how policy makers may influence financial market developments and market-based solutions to some of the challenges associated with managing longer-term systemic risks. It focused on how some of the policy levers available to governments may be utilized to progress or complement reform efforts. A central message is that governments need to approach these challenges as a risk manager, considering their explicit, implicit, and contingent obligations. In doing so, they are likely to benefit from greater market inputs and risk management instruments, including the ability to better measure and monitor such obligations (e.g., volatility measures).

To date, only a few governments have approached these financial challenges in this manner. Only in the past few years have longer-term projections been prepared and published by some ministries of finance and public auditors, addressing the issue of aging-related spending trends and longer-term fiscal sustainability. Similarly, few central governments publish balance sheets using accounting standards similar to those applied to private corporations, and the risks and magnitude of contingent liabilities in government accounts are rarely quantified. These emerging practices and trends should be encouraged.34

Furthermore, given the focus that rating agencies, in particular, are increasingly applying to sovereign borrowers’ long-term fiscal issues, and the potential for rating downgrades if such risks are left unaddressed, greater action may soon be required.35 Indeed, while the often shorter-term focus of politicians and the electorate may inhibit more immediate efforts to address these challenges, greater scrutiny from public auditors and legislators, financial media, international financial institutions, and investors will increase the emphasis on these systemic challenges and on the need for governments to pursue more comprehensive risk management strategies.

The issues related to these longer-term and other systemic risks, and their implications for financial markets, are relevant to all countries. Several governments and international institutions have acted to raise public awareness of the challenges related to these risks, and have begun to address some of the issues. However, these issues are not going to fade away. On the contrary, these tend to be cumulating risks, and with time may well exacerbate a number of related social, economic, and financial challenges. Moreover, governments, domestic businesses, and financial markets compete globally for investment capital. The potential economic and financial market impact of pension and health-care-related obligations, as well as food and energy security, may adversely influence the competitive positions, as well as the macroeconomic and financial stability of nations. These prospects should strongly encourage policy makers to build greater public support for more immediate policy initiatives designed to mitigate such adverse impacts. Given the multigenerational nature of the challenges and most of the likely reforms, it is important to move forward more ambitiously and more comprehensively to address these risks.

NOTES

* The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

1. These data do not include “life settlement” transactions, where a whole-life insurance policy is sold by the beneficiary or insured for an amount greater than its surrender value, but lower than the policy's face or insured value; see Stone and Zissu (2006).

2. For a typical CAT bond, issuance proceeds are invested in collateral to ensure that all interest, principal, and CAT-contingent payments can be made in a timely manner. The issuers of the four bonds in question opted to hold lower-quality collateral, coupled with a total return swap with Lehman Brothers, to protect against any collateral deterioration.

3. According to Goldman Sachs, at year-end 2009 there were about $24 billion life insurance transactions outstanding and almost $13 billion of CAT bonds and sidecars (see following). There had been almost $18 billion of CAT bonds and sidecars outstanding at year-end 2007.

4. Swiss Re has issued four parametric extreme mortality bonds (Vita Capital I, Vita Capital II, Vita Capital III, and Vita Capital IV) totaling $1,537 million, and Scottish Re followed with a similar $155 million issue (Tartan Capital), AXA with a $444 million transaction (Osiris Capital), and Munich Re with a $100 million transaction (Nathan Re).

5. The policies are reinsured through a captive special purpose reinsurance vehicle that does not face similarly high reserve requirements, and the transaction is structured so that the losses that exceed economic reserves are transferred to capital markets.

6. About $4 billion of embedded value bonds were issued in 2007 (the peak year) and about $7 billion prior to 2007. By comparison, according to the American Council of Life Insurers, U.S. life insurers collected $149 billion in premiums in 2006, and the amount of life insurance in force was $19 trillion.

7. Between 1997 and 2005, natural CAT bond issuance fluctuated between about $700 million (1997) and $2,000 million (2005), increasing to about $4,700 million in 2006 and $7,000 million in 2007 (GC Securities 2008). From 1997 to 2007, of the total $22 billion in CAT bonds issued, in terms of expected loss, $14 billion covered U.S.-based perils, $5 billion European-based perils, and $3 billion Japan-based perils (GC Securities 2008; Lane Financial 2008). In comparison, global insured natural CAT losses were about $23 billion in 2007, and ranged from $10 billion to $30 billion in 1990–2006 (indexed to 2007 U.S. dollars), except for 2006, which spiked to over $100 billion (Swiss Re 2008).

8. In fact, achieving high-end investment-grade (IG) credit ratings (e.g., AAA and AA) may be a key to CAT bond market growth. The bulk of the issuance has been non-IG, and rating agencies have been reluctant to break through the AA ceiling. In fact, S&P has set an explicit AA rating on natural CAT bond ratings, and Moody's seems to have set an Aa1 ceiling.

9. An ILW incorporates indemnity and index triggers, both of which must be realized for a claims payment to be made (see also Green 2006).

10. Sourced from various Aon Benfield (www.benfieldgroup.com) publications.

11. See Moody's Investors Service (2006b).

12. In 2006, Credit Suisse introduced a U.S. longevity index based on publicly available U.S. government mortality tables. The underlying U.S. mortality tables are updated annually with a three-year lag, which is typical of the timeliness of G-10 official mortality data. In 2007, J.P. Morgan introduced similar annually updated indices (LifeMetrics), which currently cover Germany, the Netherlands, the United States, England, and Wales. Also in 2007, Goldman Sachs introduced a mortality/longevity index (QxX) aimed at the U.S. insured population over the age of 65, directed primarily at the life settlement industry (see note 2). However, Goldman shut that operation down in late 2009. In 2008, the Deutsche Bourse introduced longevity indexes (Xpect), which cover Germany and the Netherlands with a monthly frequency.

13. See Case and Wachter (2005). Due to poor liquidity in the initial CME contracts, two paired exchange-traded funds were launched in 2009 that allowed investors to take a leveraged position on the extent to which the 10-City Composite Case-Shiller house price index would rise or fall over the next five years. However, greater trading activity now occurs in the brokered over-the-counter (OTC) market in contracts tied to Radar Logic's RPX indices for prices per square foot paid for residential real estate in 25 U.S. metropolitan areas. The United Kingdom has a reasonably liquid OTC market in futures and swaps on the national Halifax house price index.

14. See Milliman's web site (www.milliman.com/expertise/healthcare/publications/mmi/).

15. See also Swiss Re (2009) for a comprehensive discussion of the use of indices in transferring insurance risks to the capital markets.

16. See Groome et al. (2006) for a fuller discussion of the scale long-term costs and risks faced by governments with respect to aging-related and health-care costs and liabilities.

17. For example, the annual Financial Report of the United States Government is intended to show, among other things, the implications of the government's long-term financial commitments and obligations. However, the Comptroller General's statement on the 2005 report suggests that the financial reporting system used by the government does not clearly or transparently reveal all of its future liabilities; see U.S. GAO (2006) for details. To present a more accurate and complete picture of the central government's net worth and financial position, France adopted a revised and more comprehensive government accounting framework in 2001 (Loi Organique Relative aux Lois de Finances), adapted from standards used by private-sector companies. However, this effort remains a work in progress, insofar as such accounts currently include only the central government, and omit future/contingent liabilities of public pensions, which are broadly summarized in an annex. Similarly, the United Kingdom has developed a system of balance sheet accounts (Whole of Government Accounts) that follow U.K. GAAP standards, and are expected to be published for the 2010–2011 fiscal year.

18. See Mills (2008) for an overview of carbon trading and weather derivatives.

19. See also Group of Thirty (2006).

20. See the Swiss Federal Office of Private Insurance (2004) solvency test white paper.

21. U.K. FSA (2006).

22. See, for example, the speech by Mr. Ong Chong Tee, deputy managing director, Monetary Authority of Singapore, at the Singapore International Insurance Conference, May 17, 2006.

23. Industry and public officials have also noted that the fragmented U.S. insurance regulatory framework restricts the U.S. authorities’ ability to assume a more influential role in international forums on these important issues (e.g., Davies 2006).

24. Swiss Re (2006).

25. See Fitch Ratings (2006), Moody's Investors Service (2006a), and Standard & Poor's (2006a).

26. See IMF (2005, Chapter III, Module 4).

27. Mutual insurers operate to maximize the benefits to their members, which may include providing coverage at lower cost than otherwise required by a market rate of return on capital.

28. Industry observers have noted that Solvency II may add pressure for further consolidation in the (European) insurance sector (see Standard & Poor's 2006c). See also comments by Walter Kielholz, of Swiss Re, in Ladbury (2006), and Swiss Re (2006).

29. Some health-care providers have realized the value of their in-house data/information, and have organized subsidiaries to collect, collate, and sell such data.

30. The development of liquid housing price index markets may also facilitate the growth of reverse mortgage products, allowing households to more easily realize an annuity-like income stream, and thus better hedge longevity risk.

31. See Fabozzi et al. (2010) for more detail on recent developments in European property derivatives markets.

32. In some instances, however, achieving neutrality in the taxation of a financial instrument may be effectively impossible for most taxpayers. For instance, the tax-favored position of owner-occupied housing in most countries makes it difficult to treat house price derivatives in a similar manner.

33. Indeed, the 2006 Pension Protection Act in the United States, for example, raised the maximum tax-deductible contribution to approximately 150 percent (including other criteria) of the applicable funding target (against 100 percent previously).

34. The IMF's Government Finance Statistics Manual (2001) and the Fiscal Transparency Manual have sought to go further by also encouraging contingent liabilities to be included in government budget documents.

35. Standard & Poor's (2006b).

REFERENCES

Aon Benfield Securities. 2009. “Insurance-Linked Securities 2009: Adapting to an Evolving Market.” December.

Blake, David, and William Burrows. 2001. “Survivor Bonds: Helping to Hedge Mortality Risk.” Journal of Risk and Insurance 68:2, 339–348.

Blake, David, Andrew Cairns, and Kevin Dowd. 2006. “Living with Mortality: Longevity Bonds and Other Mortality-Linked Securities.” Cass Business School Pensions Institute Discussion Paper, PI-0601, January.

Bodie, Zvi, and Robert C. Merton. 2002. “International Pension Swaps.” Pension Economics and Finance 1:1, 77–83.

Brown, Jeffrey R., and Peter R. Orszag. 2006. “The political economy of government issued longevity bonds.” Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Longevity Risk and Capital Market Solutions at the Cass Business School, April.

Case, Bradford, and Susan Wachter. 2005. “Residential real estate price indices as financial soundness indicators: Methodological issues.” In Real Estate Indicators and Financial Stability. Proceedings of a joint BIS-IMF conference in Washington, DC, October 27–28, 2003. Bank for International Settlements.

Cox, Samuel H., and Yijia Lin. 2005. “Natural Hedging of Life and Annuity Mortality Risks.” Georgia State University Center for Risk Management Insurance Research Working Paper 04–8, July.

Davies, Sir Howard. 2006. “A Word of Advice to Hank Paulson.” Financial Times, July 5, 15.

Dowd, Kevin, David Blake, Andrew Cairns, and Peter Dawson. 2005. “Survivor Swaps.” Journal of Risk and Insurance 73:1, 1–17.

Fabozzi, Frank J., Robert J. Shiller, and Radu S. Tunaru. 2010. “Property Derivatives for Managing European Real-Estate Risk.” European Financial Management 16:1.

Fitch Ratings. 2006. “Exposure Draft: Insurance Capital Assessment Methodology and Model (Prism)—Executive Summary.” Fitch Ratings Insurance Criteria Report, June.

GC Securities. 2008. “The Catastrophe Bond Market at Year-End 2007.” GC Securities.

Green, Meg. 2006. “Hot CAT Contracts.” Best's Review, April.

Groome, Todd, Nicolas Blancher, Parmeshwar Ramlogan, and Oksana Khadarina. 2006. “Population Ageing, the Structure of Financial Markets and Policy Implications.” G-20 Workshop on Demography and Financial Markets, Sydney, Australia, July 23–25.

Group of Thirty. 2006. Reinsurance and International Capital Markets. Study Group Report. (Washington, DC, January).

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2005. “Global Financial Stability Report.” World Economic and Financial Surveys. Washington, DC, September.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2006. “Global Financial Stability Report.” World Economic and Financial Surveys. Washington, DC, April.

Ladbury, Adrian. 2006. “Head for the Capital.” Insurance Day, May, 24–25.

Lane Financial. 2008. “The 2008 Review of ILS Transactions.” Lane Financial LLC, March 31.

Lin, Yijia, and Samuel H. Cox. 2005. “Securitization of Mortality Risks in Life Annuities.” Journal of Risk and Insurance 72:2, 227–252.

Mahul, Olivier, and Jerry Skees. 2006. “Piloting Index-Based Livestock Insurance in Mongolia.” World Bank Group AccessFinance Newsletter, March.

Milevsky, Moshe A. 2006. The Calculus of Retirement Income: Financial Models for Pension Annuities and Life Insurance. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Mills, Paul S. 2008. “The Greening of Markets.” Finance and Development, International Monetary Fund, March, 32–36.

Moody's Investors Service. 2006a. “Company Built Internal Models Expected to Play Greater Part in Moody's Insurance Rating Process.” Moody's Investors Service Global Credit Research Special Comment, June.

Moody's Investors Service. 2006b. “Reinsurance Side-Cars: Going Along for the Ride.” Moody's Investors Service Global Credit Research Special Comment, April.

Poterba, James M. 1997. “The History of Annuities in the United States.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 6001, April.

Standard & Poor's (S&P). 2006a. “Credit FAQ: An Advance Glimpse at the Upcoming Changes to the Insurer Capital Model.” RatingsDirect, June.

Standard & Poor's (S&P). 2006b. “Global Graying: Aging Societies and Sovereign Ratings.” CreditWeek, June 7, 55–66.

Standard & Poor's (S&P). 2006c. “Credit FAQ: The impact of Solvency II on the European insurance market.” RatingsDirect, July.

Stone, Charles A., and Anne Zissu. 2006. “Securitization of Senior Life Settlements: Managing Extension Risk.” Journal of Derivatives (Spring).

Swiss Federal Office of Private Insurance. 2004. White paper on the Swiss solvency test, no. 2, November.

Swiss Re. 2006. “Solvency II: An Integrated Risk Approach for European Insurers.” Sigma, no. 4.

Swiss Re. 2008. “Natural Catastrophes and Man-Made Disasters in 2007.” Swiss Re.

Swiss Re. 2009. “The Role of Indices in Transferring Insurance Risks to the Capital Markets.” Swiss Re.

Syroka, Joanna. 2006. “Macro-Level Weather Risk Management for Ethiopia.” International Task Force on Commodity Risk Management in Developing Countries, presentation given at annual meeting, Pretoria, South Africa, May.

UK FSA (Financial Services Authority). 2006. “Implementing the Reinsurance Directive.” CP06/12, June.

U.S. GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2006. “Fiscal Year 2005 U.S. Government Financial Statements.” Washington, DC, March.

Watson Wyatt. 2005. “The Uncertain Future of Longevity.” Watson Wyatt/Cass Business School Public Lectures on Longevity, March.

World Bank. 2005. “Managing Agricultural Production Risk: Innovations in Developing Countries.” World Bank Agriculture and Rural Development Department, Washington, DC.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Todd Groome, former advisor to the Monetary and Capital Markets Department for the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was appointed chairman of the Alternative Investment Management Association (AIMA), the global organization of the hedge fund industry, in January 2009. Mr. Groome has significant financial markets experience, developed over an extensive career in capital markets, in both the public and private sectors. Before the IMF, Mr. Groome served as managing director and head of the Financial Institutions Groups of Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse in London, focusing primarily on debt capital markets and on capital and balance sheet management for banks and insurance companies. Prior to that, he worked with Merrill Lynch in London and New York as part of the Financial Institutions Corporate Finance Group working on mergers and acquisitions (M&A), advisory, and debt and equity financing for banks and insurers. Before moving to London in 1989, he worked as an attorney with Hogan & Hartson in Washington, DC, as part of the Financial Institutions Group. Mr. Groome holds an MBA from the London Business School, a JD from the University of Virginia School of Law, and a BA in Economics from Randolph-Macon College (where he was awarded the Wade C. Temple Scholarship for Economics, and graduated Phi Beta Kappa). He is also currently a visiting scholar at the Wharton Business School, University of Pennsylvania.

John Kiff has been a senior financial sector expert at the International Monetary Fund since 2005. Prior to that he worked at the Bank of Canada, where he was involved in various financial markets analytic and trading activities. Since 1999, John was heavily involved in several BIS working groups that focused on credit risk transfer markets, and he published a number of articles and papers around these projects. At the IMF, John is part of the team that produces the semiannual “Global Financial Stability Report,” and he has continued to publish articles and papers on risk transfer markets. More recently, he has been focusing on mortgage securitization markets.

Paul Mills joined the U.K. Treasury in 1992, after having studied for a PhD in financial economics at Cambridge University. After periods in macroeconomic modeling and financial regulation, he specialized in government debt management, culminating in establishing the U.K. Debt Management Office in 1998. Paul remained at the DMO as head of policy and deputy CEO until returning to the Treasury in 2000 to lead policy sections managing the U.K. government's balance sheet (debt, cash, and currency reserves), then financial stability and regulation. He joined the International Monetary Fund in 2006 and has worked on global financial stability, the U.S. financial system, innovative risk transfer, climate change and financial markets, and Islamic finance. He now works in the IMF's London office focusing particularly on financial stability and regulatory policy.