Recent developments in relationship portfolios: a review of current knowledge

Abstract

Recent developments in relationship portfolio research are reviewed including contextuality, their significance in technology-intensive industries and innovation, portfolio dynamics and developments in customer lifetime value and other finance-based models. The interfaces between CRM, segmentation and portfolio analysis are also considered. The managerial implications are presented; these highlight the ongoing usefulness of portfolio analysis as a strategic decision-making tool.

Introduction

For business, relationship management is as central today as it was 30 years ago. Academic focus has moved from the marketing mix (e.g. Borden 1964) through relationship marketing (e.g. Grönroos 1994; Payne et al. 2005) to the current discourses on customer experience and engagement (e.g. Brodie et al. 2011), value (e.g. Ettenson et al. 2013; Ngo and O'Cass 2009; Woodruff 1997) and service-dominant logic (e.g. Grönroos 2011; Vargo and Lusch 2011). Nonetheless, it is the firms that successfully manage and meet the needs of their customers profitably that remain at the forefront of business. While customer relationship portfolios do not attract extensive attention, they remain an underlying theme in much of the research that is undertaken into strategic account management and strategy itself, and reflect the increasingly strategic role of business-to-business marketing (Wiersema 2012) and sales (Geiger and Guenzi 2009). Yorke and Wallace (1986) noted key problems in business marketing that customer selection helps to solve: achieving a true marketing orientation and strategic flexibility. Recent research by Schiele (2012) adds another perspective to this consideration with respect to the idea that customers are competing to become ‘preferred customers’ in an open innovation context where they are seeking the most innovative suppliers to collaborate with. Additionally, as Gök (2009) notes, portfolios form the basis of key account management (KAM), yet often KAM lacks the insight into customer needs that portfolio analysis can provide.

The importance of relationship portfolios (i.e. customer and supplier portfolios) in resource allocation decisions is recognized extensively by Industrial Marketing and Purchasing Group (IMP) researchers (e.g. Håkansson 1982; Terho and Halinen 2007; Turnbull et al. 1996) and purchasing scholars (e.g. Kraljic 1983; Krapfel et al. 1991). Pels (1992) highlights the importance of tools of this nature when dealing with concentrated demand, particularly when a firm is serving a limited number of clients either by choice or as a result of an oligopsonic market structure. However, there is also considerable evidence of the success of portfolio analysis in more competitive markets (e.g. Johnson and Selnes 2004; Turnbull and Zolkiewski 1997; Wuyts et al. 2004). From a marketing and sales management perspective, relationship portfolio analysis is important when clients are particularly active and relationships are important, and companies need to be able to identify the optimum resource allocation across their customer base. This is of central importance in KAM in that it allows account managers to actively focus on their most important accounts. Terho and Halinen (2007) suggest that viewing customer portfolio analysis simply in terms of the application of matrix-based models is inconsistent with what firms actually do. They propose a broader definition of portfolio analysis, as ‘an activity by which a company analyses the current and future value of its customers for developing a balanced customer structure through effective resource allocation to different customers or customer groups’ (p. 721).

The following sections present a review of the extant research into relationship portfolios and highlight the key themes that are emerging as points of discussion and practice. The managerial implications of these issues are then considered.

Review of extant research

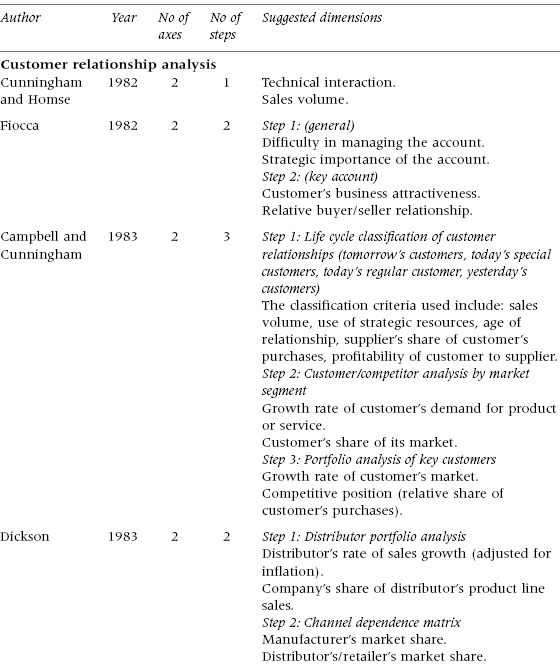

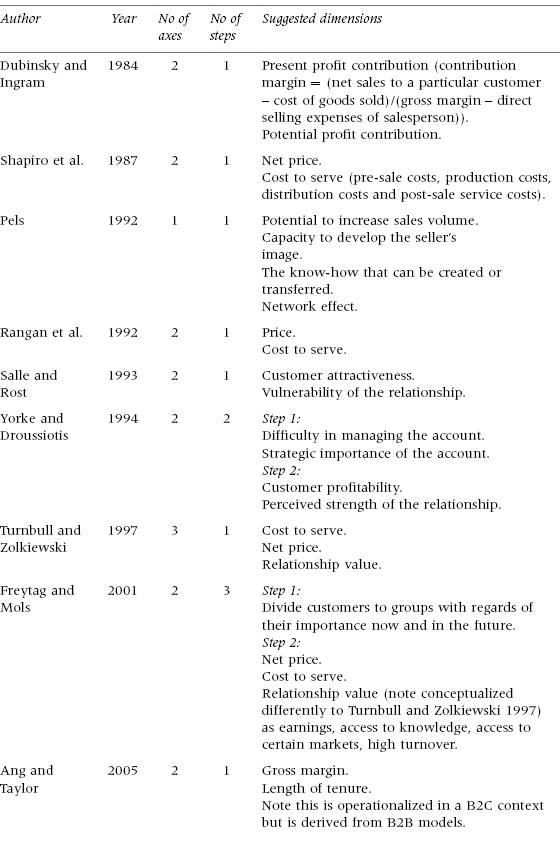

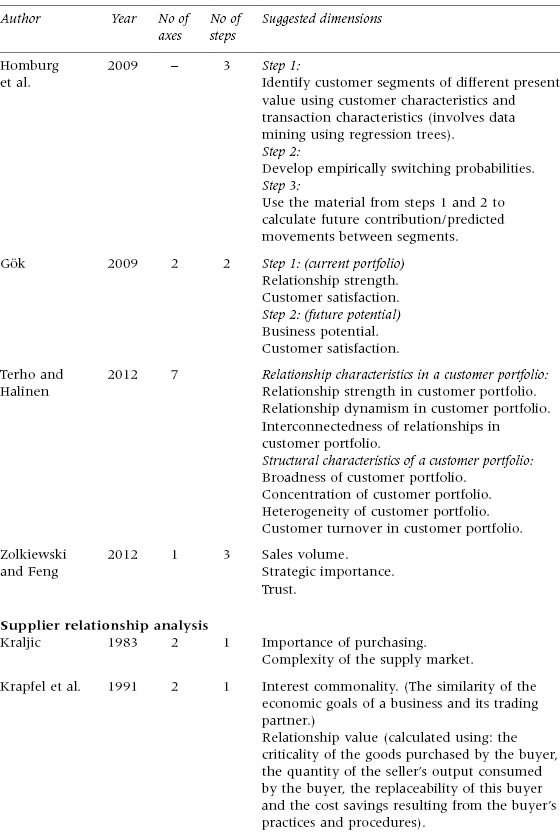

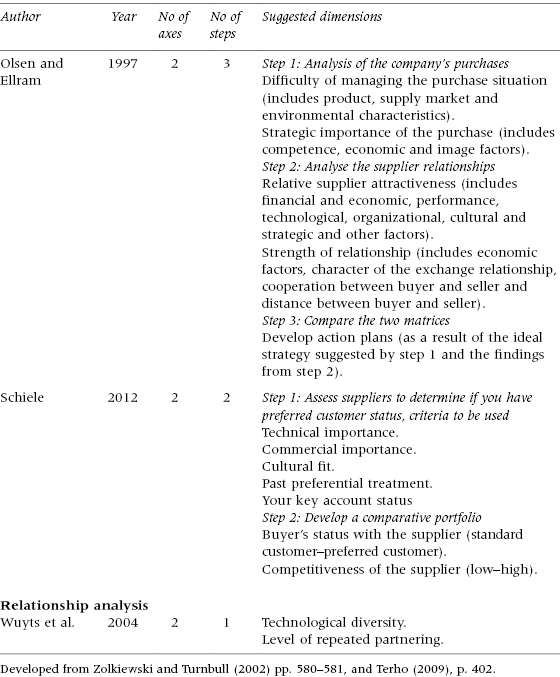

Reviews of the work on relationship portfolios can be found in Zolkiewski and Turnbull (2002) and Terho (2009). It is not our purpose to restate this work; however, Table 1 provides an updated list of relevant research into relationship portfolios drawing on both buyer and supplier perspectives. In supplier relationship management, supplier portfolios are widely adopted; for example, Gelderman and van Weele (2003) and Caniëls and Gelderman (2007) note the widespread use of Kraljic's model. However, there appears to be a wider variation in the way that customer portfolio analysis is undertaken (Terho and Halinen 2007), perhaps because many sales strategies are opportunistic in nature (Yorke and Wallace 1986). This suggests that customer portfolio analysis is not a simple implementation and adoption exercise, but rather that it needs careful planning and to be an integral part of KAM.

Talwar et al. (2008) suggest that there is limited evidence of explicit adoption of matrix-based relationship portfolio analysis in a marketing context. For example, Talwar et al.'s (2008) empirical evidence suggests that customer portfolio management is based on a division (segmentation) of customers into groups defined by their value-seeking activity. A management process is then used to allocate them into the most appropriate contact pattern, e.g. call centre versus fully fledged KAM. The selling process is also used to try to migrate customers along this continuum. This is consistent with the dichotomy proposed by Salle et al. (2000) between strategic and operational use of portfolios. Terho (2009) suggests that relationship portfolio analysis needs to be viewed as strategic, have the support of senior management and involve good cross-functional cooperation.

One practical application of customer portfolio modelling is reported by Ang and Taylor (2005). They developed a customer portfolio model for a business-to-consumer context, an internet service provider, and utilized data on over 130,000 customers. They took a relatively simple approach by considering only gross margin (not including acquisition costs) and length of time the customer had been with the provider. They then used the results of the analysis to employ different relationship management strategies according to the quadrant in which a customer resided. For example, highly profitable short-term customers were offered an incentive to encourage them to take a longer-term contract, while stars were encouraged to become advocates by signing up a friend (Ang and Taylor 2005). Their data show some migration into the highly profitable long-term quadrant, but whether this would have happened even if no intervention had been made is not apparent. However, Ang and Taylor (2005) demonstrate that customer portfolio management can have recognized and successful outcomes.

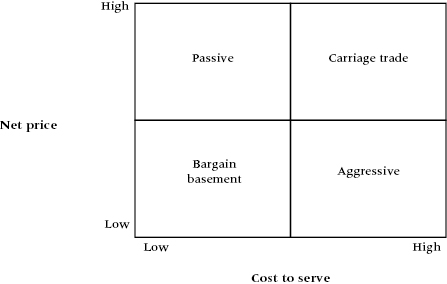

Salle et al. (2000) observe that the different portfolio models are grounded in different perspectives on how resources should be allocated. They argue that Dubinsky and Ingram (1984), for example, use the modelling for allocation of sales resources according to assessment of profit contribution, both existing and potential. Meanwhile, the models rooted in an IMP tradition involve multi-dimensional customer–supplier relationships, which include issues such as technological interaction and the importance of the overall relationship, and could therefore be argued to be more of a strategic than tactical nature. In this respect, it can be suggested that the models rooted in a relational tradition are much more useful to key account managers, as these models allow for the identification of the critical customers for the company concerned; see, for example, how key accounts were positioned on the Shapiro et al. (1987) customer classification matrix by Turnbull and Zolkiewski (1997) in Figure 1. It can be seen how this portfolio approach highlights the accounts that deserve most attention, i.e. ‘passive’ and ‘carriage trade’.

Figure 1 Key account positioning on the Shapiro et al. matrix

Source: reproduced from Turnbull and Zolkiewski (1997), p. 316

Understanding of broader relational constructs, such as trust, power and dependence, is also important in relationship portfolio analysis and consequently in KAM. These constructs should not be ignored when undertaking portfolio analysis. Johnson and Selnes (2004) and Zolkiewski and Feng (2012) note the importance of trust in portfolio analysis while Dickson (1983) and Caniëls and Gelderman (2007) identify the influence of power and dependency in the assessment of a portfolio. Ivens and Pardo (2007) concur; they empirically demonstrate that careful attention to managing the relationship with key customers results in increased commitment from those customers. This illustrates the complexity of portfolio dimension definition and calculation and emphasizes the need for subjective (management insight) as well as objective assessment, particularly when the portfolio analysis is being used to aid the identification of key relationships which need to be developed. Zolkiewski and Turnbull (2002) also concur with Salle et al. (2000) that portfolio analysis needs to be extended to consider the implications of the wider network within which a company, its suppliers and customers are embedded, again indicating a more strategic than operational approach to customer management.

Contextuality of portfolio analysis

Another important avenue of research has been developed by Terho and Halinen (Terho 2008, 2009; Terho and Halinen 2007, 2012), whose work explores the contextuality of portfolio analysis. Their findings suggest that in low- and medium-complexity environments more formal practices ensue, while when relationships are more intensive (highly complex contexts) management at the portfolio level is not evident (Terho and Halinen 2007). They see different customer portfolios arising to reflect different exchange conditions, and integrate perspectives from the marketing environment view and the interaction and networks perspective to analyse these (Terho and Halinen 2012). From this perspective they analyse the portfolio using seven dimensions: ‘broadness, concentration, heterogeneity of the customer base, customer turnover, the strength of relationships, the dynamism of the relationships and the interconnectedness of relationships in the portfolio’ (pp. 340–341) and see this as providing an empirical classification of portfolios.

Terho (2009) also develops a formative construct for customer portfolio management, comprising four dimensions: analysis efforts, analysis design, responsiveness efforts and responsiveness design. This construct highlights the multi-level and inter-functional nature of customer portfolio management. He emphasizes the need to consider both strength and style of management practices.

Portfolios in technology-intensive industries

Customer portfolios have also been specifically identified as important factors in areas such as new product development for young technology-based firms (Yli-Renko and Janakiraman 2008) and capability development for SMEs (Furlan et al. 2009), which illustrates how the identification of the key customers is critical in all sizes and types of company. Wuyts et al. (2004) observe the importance of using a portfolio approach to maximize the impact of effective knowledge transfer with respect to R&D relationships. Their findings are derived from the pharmaceutical industry where they see technological diversity as having a positive impact on both radical and incremental innovation, while the level of repeated partnering only affects radical innovations. This is argued to be because ongoing relationships facilitate complex knowledge transfer.

Wuyts et al. (2004) also find that diverse portfolios facilitate inter-organizational learning. Meanwhile, Yli-Renko and Janakiraman (2008) have observed an inverse U-shaped relationship between the number of new products developed and customer portfolio size. Additionally, they note that relational embeddedness is also a significant factor if the portfolio size is too small or large, suggesting again that factors such as relationship quality and more subjective elements relating to relationship management have to be given equal attention in portfolio management decisions.

Dynamics and portfolio analysis

Portfolio analysis is criticized for being often used as a static analysis. However, portfolios can be used effectively to monitor relationship dynamics. Indeed, it is often the key account manager's role to monitor these dynamics. For example, Furlan et al. (2009) show that as Italian SMEs develop marketing and design capabilities the composition of their customer portfolio changes, resulting in an increase in collaborative relationships. Homburg et al. (2009) argue that it is essential that the dynamic nature of customer portfolios is considered in any analysis. They suggest that there has been limited focus on capturing dynamics as part of portfolio analysis. However, some earlier work has focused on changes to the customer portfolio over time (Ang and Taylor 2005; Shapiro et al. 1987; Turnbull and Zolkiewski 1997) but this work has been retrospective rather than prospective.

Key to these dynamics is an understanding of how key account management strategies are influencing these changes. Clarke and Freytag (2013) note the importance of orchestrating the portfolio, not least by ensuring alignment with respect to key customers' strategic aims. Through introducing a customer lifetime value model that takes into account switching behaviour, Homburg et al. (2009) make the issue of dynamics into a central aspect of strategic decision-making around customer portfolios. They also force the consideration of future risk related to both individual customers and different segments. It is argued more widely that customer or segment risk analysis should be seen as one of the underlying principles behind portfolio management (e.g. Ryals 2002). Bolton and Tarasi (2006) also highlight the balancing or optimization of risk and return as being a central managerial challenge related to portfolio management.

Homburg et al. (2009) propose two strategies for dealing with customer/segment risk: an offensive approach which seeks new customers and also focuses on developing existing customers, while a defensive approach aims not to lose customers or let their value contribution deteriorate. As part of this they see a need for observing customer behaviour to determine what the drivers are for switching and including this in the portfolio analysis, resulting in a complex three-step contextually-based analysis tool (their data show considerable differences between sectors). Such observations are essential in order to understand the value contribution made by key customers, especially because Homburg et al. (2009) suggest that value contribution deterioration may be more detrimental to an organization than actually losing a customer. They also discuss the importance of considering deteriorating relationships and the strategy to ensure that the decline in value of the contribution that customers, including key customers, is not overlooked. They argue that this approach highlights that marketers are in danger of focusing on inappropriate key accounts/customers/segments if they only rely on static analysis.

Switching behaviours are only one form of relationship dynamic; there are others such as changes in patterns of spending that also need to be considered. This issue of dynamics or changes that occur over the life cycle of a relationship is also beginning to be explicitly investigated in KAM, with authors such as Hsieh and Chou (2011) noting the changes in alignment between key account customers and the supplier; observing that they varied over the relationship life cycle and involved passive, opportunistic, mutualistic and compensatory forms of alignment. These forms of alignment should also be considered as relevant to portfolio assessment.

An alternative issue relating to the dynamic nature of relationships and specifically focusing on temporality comes from Mota and De Castro (2005) who point out that due to the learning processes that take place in relationships, the dimensions used to assess customer portfolios need to be changed to reflect such learning processes. Taken to the extreme, this implies that a dynamic set of axes need to be employed to cater for learning and capability development within relationships and especially those with key customers.

Customer lifetime value and other financially derived models

The manner in which customer portfolios are used to guide the day-to-day management of relationships has also evolved into a discussion of customer lifetime value, and customer portfolio lifetime value, e.g. Johnson and Selnes (2004). Johnson and Selnes (2004) highlight the dynamic nature of such relationship management processes. They focus on value creation and the different ways in which it is created as their portfolio analysis criteria and note three different strategies for customer value creation: ‘parity value, differential value and customized value’ (p. 2). However, the calculation of lifetime customer value is fraught with difficulties; it relies on predictions and the categorization of customers into a typology of strangers, acquaintances, friends and partners (Johnson and Selnes 2004) and implies a progression to increased value. This progression towards increased value or profit was also included in Shapiro et al.'s (1987) work. However, Turnbull and Zolkiewski's (1997) empirical work does not reflect an upwards steady progression of profit; rather, their results show that ‘partner’ relationships (key accounts) may not provide the increase in value or profitability that is anticipated. It may be that this type of projection is not reflective of the dynamics and uncertainty in the environment. Additionally, it supports Håkansson and Snehota's (1995) views that close relationships can be restrictive and preclude a company from more profitable interactions. Perhaps it is more important that this type of analysis should encourage a company to consider how it can balance its stronger and weaker relationships (Johnson and Selnes 2004) and reflect critically upon which customers it identifies as key accounts.

Nonetheless, the use of financial models and theory to calculate portfolio value as a tool to optimize customer portfolio performance and management has been receiving increasing attention (Ryals 2002, 2003; Tarasi et al. 2011). Ryals (2002) considers the implications of using financial metrics to calculate the value of a customer or segment by looking at the ratio determined by comparing future cash flows with the weighted average cost of capital. She notes the difficulties of assessing customer risk and suggests that the traditional risk scorecard may not capture all the risks associated with a customer, e.g. risk related to changes in purchasing patterns. Ryals (2002) then promotes the view that incorporating an awareness of customer risk can help managers develop targeted relationship strategies to both reduce risk and increase the value of the customer/key account.

Tarasi et al. (2011) illustrate that financial portfolio theory can be used to develop an efficient customer portfolio that appears to outperform the firm in question's existing portfolio. Notwithstanding the actual limitations of the analysis undertaken, financial portfolio theory can be argued to be problematic. Selnes (2011) observes that marketers have always taken a simple diversification approach to their customer portfolios, but financial portfolios are more complex, aiming for low correlation of returns. Tarasi et al.'s (2011) approach equates customers to financial assets which, according to Selnes (2011), does not take into account issues such as how the customer portfolio relates to a company's production function or innovation. Nor does this allow for recognition of the strategic need to identify key customers. At the same time this approach adds to the complexity versus simplicity argument that relates to the dimensions used in the analysis, where too much complexity may obscure the simplicity of the portfolio approach and too little may mean that important variables are overlooked (Gök 2009; Olsen and Ellram 1997).

Using financial models to help optimize portfolios makes a number of underlying assumptions about the data that are available to a marketing or account manager. For example, it assumes that activity-based costing is being implemented by the firm and is accessible to the marketer; yet, as Yorke (1984) notes, the costs of acquiring, retaining and motivating customers to buy are lost in an amorphous and often large item called ‘sales and marketing expenses’ (p. 21). Billett (2011) also notes that the access and transaction costs for customer segments are not homogenous and therefore may differ from firm to firm. This is even more so for key customers. Another issue relates to the accuracy of the data in the customer relationship management (CRM) system used to support this type of analysis (Ryals 2002) and ensuring that the system is regularly updated, otherwise the data cannot give an accurate picture of the customer portfolio. The cost of data mining is another consideration; there is lack of consensus about how this can be determined but it is recognized to be significant (Marbán et al. 2008). And, of course, ability to predict the future is an art not a science; Tarasi et al. (2011) quote Bernstein (1999) who notes that even the most brilliant mathematician cannot predict the future. An additional concern is the implication that you can choose which customers you have and control the costs to serve them (cf. Shapiro et al. 1987).

Customer relationship management and relationship portfolios

IT is changing practice extensively (Geiger and Guenzi 2009) and it could be argued that technology is undermining the need for managers to understand portfolios, with more focus falling onto a discussion of CRM systems and their implicit algorithms as well as the use of other sales technology (Hunter and Perreault 2007). However, Hunter and Perreault (2007) also point out that the technology cannot manage relationships and that personnel need to be involved in it. Bolton and Tarasi (2006) also emphasize the need to consider both systems and processes as well as recognizing that, if used correctly, CRM systems can provide supporting metrics for customer portfolio management.

Bohling et al. (2006), however, note the patchy success of CRM implementation and put this down to lack of top-level management support and strategic integration. Johnson et al. (2012) also note the reluctance of firms to fully embrace CRM principles, suggesting that product and sales-led philosophies militate against true customer-centric operations.

Given the discussion that there has been about CRM, its adoption and its success, it is somewhat surprising that there is limited empirical business-to-business research into the adoption of CRM systems (Ata and Toker 2012). Hence, Ata and Toker (2012) explore the adoption of CRM in a Turkish context and demonstrate a positive impact of CRM on both customer satisfaction and organizational performance. They define CRM as ‘a strategic macroprocess aiming to build and sustain a profit-maximizing portfolio of customer relationships’ (p. 497) and illustrate its relationship with portfolio management. Ata and Toker (2012) also note that CRM adoption is often not a strategic decision but more tactical and see that this concurs with the findings of Bohling et al. (2006). Such views give strength to the argument that customer portfolio analysis is important as it can be argued to be more focused than CRM solutions. It is the senior managers who need to make the strategic decisions and, together with the sales force, they have to consider customer acquisition, retention and divestment, and this is where the notion of the customer portfolio has its primacy.

Segmentation and/or portfolio analysis

A perpetual question that remains when discussing customer portfolio analysis is how it is related to market segmentation. Homburg et al. (2009) and Tarasi et al. (2011) use customer segments as their unit of analysis rather than individual relationships, which suggests that customer portfolio management could be used either as a tool to focus on individual relationships or more broadly to focus on customer segments according to the size of the customer base and the characteristics of the customers. However, this moves away from the principle of using segmentation bases to analyse the majority of customers and portfolio analysis to analyse key accounts (Zolkiewski and Turnbull 2002).

Bolton and Tarasi (2006) comment on the applicability of segmentation and emphasize that the point of segmentation is to identify a group of customers who have the same needs and requirements. However, segmentation, in business-to-business markets, can be argued to be a useful but anonymous tool (Zolkiewski and Turnbull 2002) that does not focus on the inter-relationships of the customers in the target market nor allow for the identification of key customers. In many contexts it could be argued to be too simplistic an approach in an IT-enabled global and networked world, where interconnections and competition through and between networks is shaping the competitive landscape (Gulati et al. 2000).

Tarasi et al. (2011) note that customer portfolio analysis is particularly relevant for business-to-business markets because in this arena firms tend to focus greater proportions of their resources on individual customers and key accounts, cf. consumer markets. Portfolio analysis is also considered to be preferable when distinct customers' requirements need to be considered rather than when clear segments of homogenous groups of customers can be discerned (Terho and Halinen 2007). In this case, customer portfolios could be argued simply to be identifying segmentation bases that are relationally driven. Indeed this has been suggested by Elliott and Glynn (1998) as a mechanism for segmenting retail banking relationships. Bolton and Tarasi (2006) emphasize that the central tenet of customer portfolios is to allow managers to progress beyond the traditional segmentation approach in order to consider the dynamic management of the key relationships in their portfolio.

The issue of managing relationships in a dynamic context is a central challenge in business-to-business marketing (Ford et al. 1986) and has been argued to be the main reason why portfolios are an inappropriate management tool, in that they can move the focus away from the relationship itself (Dubois and Pedersen 2002). Nonetheless, managers still need mechanisms to determine which relationships they should resource and to help in the identification of key accounts; relationship portfolio analysis is specifically designed to analyse relationships and to help with these decisions. So as long as this analysis takes dynamics into consideration it is a good mechanism to support such decision-making.

Managerial implications

The review above shows that there are multiple relationship portfolio models, covering customers, suppliers and relationships generally, which are based upon different levels of analysis, individual customers and market segments, and which can be used tactically and strategically. Hence, it is necessary to consider what this means for business-to-business marketing and key account managers.

It is important for managers to consider the insight that relationship portfolio analysis can bring to understanding their key customers' needs and also how to allocate relevant resources across their portfolio of customers/suppliers. This is particularly important when customers perceive themselves to be in a relationship with the supplier or vice versa. However, if portfolio analysis is applied retrospectively only, it brings with it the danger that the focus will be on past issues rather than understanding and meeting customers' changing needs. Additionally, there is a danger of simply focusing on existing customers and forgetting to search for new customers and/or relationships and, in turn, considering their impact on the existing portfolio. As well as encouraging managers to seek new relationships, when adopted strategically, relationship portfolio management should encourage managers to consider fading relationships as well as those that need to end because they no longer fit with the strategic direction of the company or because they are simply demanding too much resource. This should be seen as central to key account management.

Managers need to be aware that portfolios can be used on a number of different levels, for example, for allocating sales resources across key accounts, or more broadly in thinking about the overall nature of a company's complete set of resources. The importance of understanding portfolios when looking for innovative partners and in R&D contexts illustrates this point. Smackey (1977) emphasizes the importance of allocating sales resources to the customers that have the most potential to contribute to a firm's profitability. Yorke and Wallace (1986) are also early contributors to this debate, reminding us that efficient allocation of marketing resources to target customers is critical to a firm's success. However, as the discussion above about understanding the importance of customer portfolios in new product development and innovation illustrates, an understanding of customer portfolios can assist in allocation of a wide range of resources. For portfolio analysis to be effective at this level, it needs strategic-level integration, top-level management support and also consideration of the wider network implications of decisions that are made.

The discussion about the range of models and dimensions provided above demonstrates that relationship portfolio analysis requires considerable strategic and critical thinking from managers. It will never fall into the genre of simply-applied strategic tools and fixes unless it is being considered in a very simplistic fashion. The contextuality surrounding the application of relationship portfolio analysis requires managers to use their knowledge and industry insight to ensure effective application of the tool, both operationally and in strategic-level thinking.

Relationship portfolio management should not be viewed as a once-a-year planning tool. It needs to be undertaken on an ongoing basis and must be used to assist in the identification and management of key accounts, to monitor relationship dynamics and to give insight into how to react to the changes observed as well as simply assessing where the company is now. It should also not be seen as a job to be done by marketing analysts or planners; it needs to be part of all managers' remits.

The more complex customer lifetime value-based analysis tools are complicated and time consuming to develop; thus they are more expensive to implement. Managers need to be certain that they have the detailed level of data needed to calculate such factors and appropriate algorithms to make the calculations relevant as well as resources to devote to the process. They should also consider if the costs of such systems do provide the returns to justify their implementation. We would suggest that such models are best used to assist in decision-making rather than becoming prescriptive mandates. They are designed to help to manage risk and as such managers utilizing these tools need to ensure that they completely understand what the risk factors are in their contexts, so a careful analysis of the risk driving factors in the area needs to be undertaken.

Relationship portfolio analysis and CRM should not be considered to be the same. They both can be central to good customer management schemas, but cannot be simply substituted for one another. Portfolio analysis should be used to guide the assignment of key account status to specific relationships. CRM should be viewed as a complementary mechanism for dealing with customers who do not warrant such careful attention. This is not to say that any customers' needs should be treated lightly, but that CRM may be more effective for dealing with customers who are being serviced through less personalized channels.

Relationship portfolio analysis necessitates the collection of detailed information about customers and their needs; which the advent of management/marketing information systems has facilitated. However, as early as 1976 Hartley noted the importance of collecting and analysing customer data to ensure improved market penetration and customer orientation, so this is not a new idea. The approach is supported by the view that marketing is primarily an information-handling problem (Holland and Naudé 2004) and perhaps suggests that an efficient and effective information collection system is the primary tool needed to ensure the success of relationship portfolio analysis. It does not negate, however, the importance of key account managers relating to, deeply understanding and personally knowing their customers.

Relationship portfolio analysis should be seen as informing strategic direction with respect to identification of the key accounts and customers that a firm has or desires. However, while Clarke and Freytag (2013) remind us to consider how we are aligned with these key customers, we need to be aware that such alignment does not imply symmetry of the relationship. It is important to recognize that key relationships are rarely symmetrical (see, for example, Ryals and Davies (2013)), and that customers' strategic intents are not necessarily the same as those of their suppliers. Awareness of this disparity will aid managerial decision-making with respect to selection of key customers and militate understanding that, while strategic intent of customers is important, it is understanding how these strategies relate to key relationships that is important in their management and selection.

In an international context, particularly in emerging economies, the use of relationship analysis is still nascent. Contextuality can be seen to be important in this arena but the limited evidence from the research discussed above (both Zolkiewski and Feng (2012) and Talwar et al. (2008) have empirical data from BRIC countries) suggests that relationship portfolio analysis is not as apparent in such economies, probably because the markets are not yet mature and it is a seller's market. However, the situation offers an opportunity to managers in that if they can use portfolio analysis effectively here they can be in a position to ‘cherry pick’ the most ‘profitable’ accounts in these emerging markets. Tsybina and Rebiazina (2013), meanwhile, observe that in a Russian context the interconnectedness of companies is very influential on the portfolio, resulting in smaller companies often being treated as key customers because of their relationships with large buyers, again emphasizing the need to consider the context in which the analysis is being performed.

Relationship portfolio analysis needs to be inextricably linked to an understanding that its prime purpose actually relates to profitability for the company that is utilizing it. Profitability may be in financial terms or more broadly defined as providing access to knowledge, innovation, other markets, etc. The important factor here is that managers recognize and understand the costs of looking after different customers and also the benefits that it brings to their organization. Managers should be aware when customers become too resource demanding, and they need to be in a position to apply different management strategies to reverse these situations. The findings discussed above do not point to a ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategy that can be applied; they show the variety of factors that needs to be considered. Managers should rely on their vision and insight to apply the most creative strategy to the context, in order that they retain the company's competitive advantage and meet their customers' needs.

Of course, the use of relationship portfolio analysis is not without critics. It can be argued that relationship portfolio analysis tools suffer from the same problems as corporate portfolio analysis tools. For example, Untiedt et al. (2012) identify problems relating to over-simplification of complex and interdependent decisions, problems with the underlying assumptions that have been made and also misapplication issues. However, Untiedt et al. (2012) also support the use of portfolio analysis and suggest that what is actually needed is research to advance it and to enable managers to understand how to differentiate between when to use the analysis diagnostically and when it should be used prescriptively. Zolkiewski and Turnbull (2002) also list additional criticisms such as problems of mixing subjective and actual data, complexity of calculating customer profitability, data distortion over time and imprecise scales. However, despite these limitations it can be argued that the benefits of formally considering and analysing your relationship portfolio far outweigh simply taking an ‘anonymous’ approach to customer and/or supplier management and acquisition.

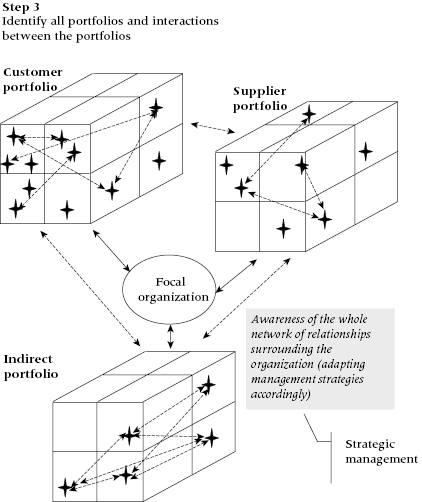

Another criticism of portfolio models is that they are unable to cope with issues such as how relationships can be used to improve efficiency and/or productivity (Mota and de Castro 2005). Similarly, Dubois and Pedersen (2002) contend that portfolio analysis actually removes focus from managing relationships in their network context and can move managers' attention away from focusing on ongoing interactions. However, Zolkiewski and Turnbull (2002) do make recommendations about how network factors can be taken into account in portfolio analysis; see Figure 2. Indeed, it could be argued that the ambition of portfolio analysis to ensure that managers consider the inter-related nature of resource decisions does force a consideration of network factors.

Figure 2 A network approach to portfolio analysis

Source: reproduced from Zolkiewski and Turnbull (2002), p. 587

Conclusion

The discussion above about relationship portfolios illustrates the heterogeneity in understanding of the term relationship portfolio; on the one hand these portfolios are simply analytic tools responding to faceless customers, while on the other they can be used to help determine future strategy of a firm and are central to key account management. This is a contextually-embedded phenomenon and it is in the hands of managers to exploit it correctly. Mota and de Castro (2005) support Gelderman and Van Weele's (2003) view that there is no single blueprint for portfolio management and that its use necessitates critical thinking. Using portfolio analysis requires a careful balance between selecting appropriate criteria and not over complicating the analysis so that it obscures the strategic decision-making it is designed to support.

We contend that, when used well, portfolio analysis can assist in identifying key accounts and ensuring all relationships that a firm is engaged with can be profitable, either financially or through providing access to scarce resources that the company needs for its ongoing success. Relationship portfolio analysis also forces managers to consider if the relationships they are engaged in are necessary for their firms' success, if they are really ‘key’ and also when they need to find additional relationships to ensure their future survival. Managers need to recognize when they are engaging in different relationships and what these relationships contribute to the firm's ongoing success.