CHAPTER

12

LISTEN

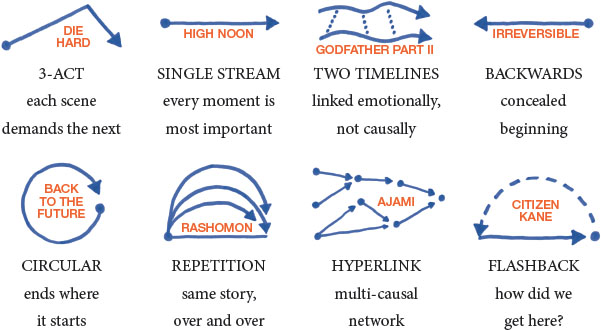

A story comes alive in the imagination of its listener. A life becomes real once it is narrated. Without a story, you would dart from moment-to-moment, embracing pleasure and fleeing hardship as each stimulus went in and out of focus. Without examination and interpretation, life reduces to mere biology. Your experience of reality is a never-ending story. Stories give you a place in the world and a place in time. Stories are how you remember the past and expect the future. Every moment, a story organizes your life by accounting for all that you see and all that you cannot see but truly believe. Information has not done its job until it impacts the story running in a person's mind. Only then has information informed. If we understand story, then we can help data come alive in a person's mind too. So let us take a critical look at the (sometimes irrational) art of storytelling. The more you know, the better you can navigate the obstacles of life. But there is a natural limit to the knowledge one can learn from their own experience. We each get only one lifetime, and that makes time precious. Stories give access to the accumulated knowledge our ancestors spent their whole lives acquiring. We get to benefit at a bargain price. That is the story of the last 5,000 years of civilization. Stories help us see what could be. Fiction is like a laboratory for life. It helps us develop alternatives and store solutions for what might happen. Stories teach us how to interact with one another. They reinforce esteemed models of behavior and chastise misdeeds with scorn. Millions of people believe they are all part of the same tribe because they all believe in the same stories. Stories are storehouses, conduits, and expanders of knowledge. They help connect staggeringly large social groups. Stories are useful. O.K., fair enough. This does not yet address the aspect of stories that offends the empiricist. Somewhere, we know that the nature of storytelling does not prioritize the truth. It prefers the sensational, the exaggerated, and the exciting. Why are stories like this? Consider an evolutionary perspective. Today, truth helps us understand reality. But the truth did not always help us survive reality. Here is a story: It is the end of the dry season and the sun is heavy. I take hold of my cane and call for my dog. Parched, we set out together across the savanna in search of water. There is no shade along the hard-baked path, just a sea of yellow grass. Walking along, all I can think about is the cool taste of water on my lips. I hardly notice the bird circling overhead, or the pair of antelope bounding away, into the hazy heat. Finally, we emerge out of the dry grass and into a clearing. There it is. I can see the watering hole. Suddenly, the dog stops. In an instant she is more alert than usual. Maybe she heard a rustle in the grass. Maybe she smells something in the air. Maybe the watering hole is just a little more quiet than usual. Looking around, things feel… different. What do they do? Approach the water or turn back? What would you do? Odds are, there is nothing awry at the watering hole today. It is unlikely that, say, a lion is waiting for the thirsty pair to step forward before it pounces. But, even a 99.9 percent chance of survival is bad odds. A one in a thousand chance of becoming lion chow can get you spit out of the gene pool. The truth—whether there actually is a lurking predator—takes a backseat to the goal of not being eaten. Total consequences win, even if the odds are small. It is better to walk away from nothing a thousand times so you can be right that one time your hunch turns out to be real. From an evolutionary perspective, the truth is a luxury good. Our biology did not keep up with how rapidly we conquered nature. The world we are wired for lags behind the world we exist in. We are no longer prey to man-eating lions, but instinctual threat detection remains. The stories we tell each other and ourselves speak to certain biases that used to help us prevail. In stories, speculation beats truth-seeking. The truth takes time and risks exposure. It is safer to assume and move on. In stories, exaggeration beats subtlety. If you are wrong and flee, you live. If you are wrong and stay, you die. In stories, excitement beats monotony. Adrenaline-juicing encounters demand our attention, then they live on as the slices of life we remember most vividly. In stories, self-deception beats rational analysis. Passionate belief in a thing is sometimes the critical piece required to make that thing real. In stories, expectation beats living in the moment. Life is hard. It helps you endure to know that traumatic experiences, eventually, end. These elements make us doubt storytelling. Stories are irrational, perhaps even animalistic. Yet, stories help us to do things that only humans do. We make meaningful connections across thousands of years. We organize massive social groups. We feel most alive when we are part of something much bigger than our individual selves. Our complicated nature prefers certain experiences. And they can tell us a little about the entertainment we enjoy. Comedies make us happy. They produce more smiles and laughs than other film genres. Yet, passionate dramas, violent adventures, and even horror films sell tickets. We yearn to be terrified, safely. We delight in scandal and surprise. We crave fake anxiety. As storytellers, we must pay attention to the natural impulse for anxiety simulation. Do not sensationalize. Do not deceive. But also, do not be afraid to entertain. If you want someone to hear you, then you must have an ear for what they listen to. Good stories build energy across their telling like a train going faster down the track toward its destination. Along the way, good stories cause the audience to endure an enjoyable amount of anxiety. Good stories also give you a reason to climb aboard for the ride. If a story moves and engages the intellect and the heart, then it is well on its way. Your mind experiences time in sequence, so it receives story in sequence too. Every story arrives across a linear flow, one beat after another. A storyteller can command this flow precisely to hold a listener's attention and bias their experience. Narrative flow puts content in the right order. It makes salient what matters for each moment. It banishes anything irrelevant from view. A tight flow can meet a listener where they are, and step them to a place otherwise incomprehensible. From the familiar to the unknown. A similar controlled sequence allows a teacher to progress students toward new knowledge. We reach new domains and higher levels of abstraction by extending what we already know. Storytellers and teachers both have a vision for where they want to take their audiences and focus their attention until that goal is achieved. If the flow is smooth, the world of the story engulfs the listener's identity, and they can enter into a flow state. It is as if their mind has stepped up to the very horizon of the story's imaginary world to absorb the narrative rush through them. How is this done? You cannot show everything, an actual experiential flow. That would bore anyway. Instead, give the listener the necessary connective tissue to keep up as the story leaps forward. In film, spatial and logical context move us forward shot to shot. If we know a hero is going on trial, we are not surprised when a scene opens on a courtroom; it is a logical connection. A wide establishing shot of the entire courtroom lets us know where we are spatially before seeing a close-up of the hero taking the stand. Both logical context and spatial orientation help us go with the flow. Connective tissue is the foundation of the escapism that takes filmgoers and novel-readers on a ride. The ride gets exciting if you can get the audience to guess where the story is heading. That is called engagement. It is great if they are guessing, but no fun if the whole story is predictable. That is called a dud. At the other end of the spectrum, a narrative with weak connections is difficult to follow. If the flow is confusing, the audience gets snapped out of their flow state. They wonder what is going on. Their identities distance themselves from the story and turn critical. To engage, the narrative must land somewhere between boring and confusing. Conventional stories order events the same way we experience them, over time. First this thing happened, and then that, and then this other thing. The familiar structure steps a protagonist through a setup-conflict-resolution arc. One adventure leads to the next in a chained sequence of cause and effect. Story sequence can illuminate many more kinds of phenomena beyond temporal continuity. Sequence can also show effect, then cause. In education, effect-cause is called an explanation. In storytelling, it is called a flashback. Sequences can contrast unlike things. Sequence can elaborate, exemplify, and generalize. Sequence can surprise by violating our expectations. Take a look at the variety of plot structures below, each paired with a classic film from cinema history. Endings satisfy. Our nature is to be curious and we are willing to stick around to find out how situations will resolve to get closure. Along the way, tension, suspense, and anticipation mount as we make short-term predictions about what will happen. Anxiety builds as we wait for the outcome. It is painful to walk away from an open question. Why do we crave closure? As mentioned before, closure helps us endure struggle. Knowing that the pain will stop makes it bearable. The unknown is the worst torture. The villain you cannot see is the most terrifying. Our need to stick around for the ending seems to go against what was said earlier about prioritizing utility over the truth. Here is the difference: Closure seems to be all about forward-looking expectation and especially concerns the social world. Truth is all about backward-looking explanation and especially concerns the physical world. Knowledge about the future is more immediately critical to survival than knowledge about the past. We care a great deal about the future and will speed into it, regardless of how well we understand the past. We look forward to the fulfillment of the end. How do we motivate an audience to desire a story's closure? If we are blunt, we raise questions directly, as I just did. More elegant stories convince the listener to ask questions on their own. The story about the watering hole never explicitly states there might be a lurking threat because it does not have to. You do that work. The engaging story is a woven mesh of audience-imagined questions and answers. As a story unfolds, and questions (Q) are answered (A), new questions are asked. Multiple levels of curiosity propel us through the story. Some take the entire work to satisfy. If a film is fast-paced and builds some anxiety-inducing curiosity, you will stay until the end. You might not watch it ever again, but you will not walk out. But those two elements—linear momentum and closure—are not enough for you to finish a whole television series. You also need to care about the characters. The story has to have meaning. Our concern for an imaginary person's safety is a strange phenomenon. But is it? We can already see the thirsty pair on the savanna in our mind, even though the story did not tell you anything about what they look like. Fictional characters live exclusively in the heads of listeners. But they sit right next to historic figures, contemporary celebrities, and memories of old friends. Are your internal images of George Washington, Tom Hanks, and Harry Potter all that different from each other? For the devoted fan, Harry might be most real. We never get complete knowledge about anyone. So we take the given story character and blend it with what we know about the world. Together, the story and our own experience synthesize a gestalt being. Our imagination projects a complete person, bringing the character to life in our minds. If the story activates you to create more, then the story becomes more alive in your head. This is how books can produce more escapism than film. A good book, even with less sensory stimulation, can be more real. Characters, real or not, are real in our imagination. We are filled with empathy for the people we project with our imagination. We recognize when another being is in pain and imagine what that hurt is like. Their experience, fiction or not, affects us. In some ways, it is easier to map your own identity to a fictional character than to a real person. Storytellers design characters specifically to receive your concern. Why does the thirsty character have a dog? I included a dog because I want you to care more about my protagonist. Empathy goes beyond feeling sorry for characters. We are also invested in them because vicarious living is fun and useful. Anything learned by experiencing their journey can help us in our own future trials. Movies can inspire us to be more romantic, more daring, and even more creative. We are social creatures, interested in better navigating our tribe. We gossip to learn about people. We follow stories to learn successful behavior strategies. Once again, story is a way to expand our knowledge. Feeling for a character is a reliable way of building meaning into a story, but it is not the only way. Let us look at another dimension of meaning with a pair of statements by E.M. Forster. First: The king died and then the queen died. Here we have two events, the king's death and the queen's death. We also have a continuity relationship between the two events. One after the other. Two facts, one relationship. Now, see what Forster does by adding one little detail: The king died and then the queen died of grief. Wow. Those two little words, of grief, change everything. We have one more fact, the queen's grief. It has a causal relationship to the queen's death. But that same grief also creates an additional correspondence. Now, we also know more about the queen's relationship with the king. His death destroyed her. One additional detail creates two new relationships. This is very different than if it had said the queen died of old age. That would not tell us much about how the king and queen got along. The real magic is that the connection between the queen and her beloved king is not explicit. You intuit it. Great stories are rich with opportunities for the listener to make connections on their own. These self-made connections help the story leap off the page and into the reader's imaginative reality. The more the story comes alive in the reader's head, the more meaningful the story becomes. It is the storyteller's challenge to convince the listeners what to be curious about. The storyteller cannot tell listeners if the story is meaningful or not. That is up to them. We have referred to the audience as readers and listeners. But really, we should only be using the singular form: reader or listener. Having an audience of thousands does not mean you are going to address the entire mass as a crowd in a stadium. People experience stories alone, in their heads. But what if you did address a stadium of 30,000 people? The magic of story would still occur in 30,000 individual imaginative minds. Address each listener on a human, one-to-one level. Novice storytellers think mechanically. Their currency of thought might be camera station, shot size, and camera angle. Master storytellers determine these details based on the relationship they want to create with the viewer. Instead of camera station, what point of view should we have? Instead of shot size, do we want to feel distant or close to the subject? Instead of camera angle, how should we perceive the subject? In good stories, narrative decisions drive technical execution, not the other way around. You see, the discourse is not the main event. What happens in the listener's head in response to the narrative is most important. Story activates and creates ideas unknown to the storyteller. E.M. Forster knew his queen's grief would make us feel differently about her relationship with the king. But he could never know that his little line would call forward my own grandparents' loving bond. My grandmother's lonely hardship after my grandfather's death is now somehow better illuminated to me. This feeling is a special product of my imagination. It is a private meaning, uniquely mine. A master storyteller engages the listener's imagination to bring stories to life. Their listeners intuit internal connections between story elements. A legendary storyteller goes beyond. Their listeners discover personal knowledge that is meaningful outside the story. These are the stories that cause us to feel more alive. Stories that make us feel alive are often symbolic. Symbols imply more than is obvious; they cannot be fully explained. They can be interpreted in many ways. Symbols can mean different things to different generations. Paradoxically, the universal symbolic is achieved with precise description. Strong story symbols are rich with specific detail and are often very personal to the creator. In contrast, the generic is impersonal. It has no emotion. The generic affords no opportunity for the individual to connect, empathize, and imagine. Powerful symbols are sometimes called archetypes, a concept I think best to let Carl Jung explain: [Archetypes] are pieces of life itself—images that are integrally connected to the living individual by the bridge of the emotions. That is why it is impossible to give an arbitrary (or universal) interpretation of any archetype. It must be explained in the manner indicated by the whole life-situation of the particular individual to whom it relates… They gain life and meaning only when you try to take into account their numinosity—i.e., their relationship to the living individual. Only then do you begin to understand that their names mean very little, whereas the way they are related to you is all-important. Stories are engines of knowledge creation, especially self-knowledge. They help us discover more. Sequence, closure, and meaning help bring story flow alive. And if stories are alive, then the successful stories are the ones that survive. A successful story is the one that keeps getting told. These are the stories that do not just help us thrive, but make us feel alive, too.