HOW THIS BOOK

CAME TO BE

I wrote this book in a room so small that we talked about using it as a closet.

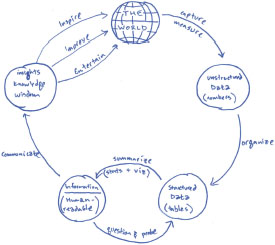

One data storytelling tradition is to follow projects with a design essay that documents some lessons learned during the process, so future creatives may benefit. In that spirit, here is a short essay about how this book took form.

A new book is just another problem that can be analyzed and solved with creativity, right? The process I forged (and endured) to make this book flowed from the practices discussed in Chapter 19. I have since learned that some parts of my process were a bit idiosyncratic, and will focus on these more unique aspects of production.

My perspective as a data storyteller was the foundation and reference point throughout this book's composition. I believe what is useful for the analysis of a data story is not always relevant to the creation of a data story. I left out what is useful only to the critic. Instead, I wrote to what I believe is useful to the creator. I also consciously reached beyond technical aspects of the craft, in search of deeper meaning. Beyond these, I included what interested me.

As soon as the book was greenlit, I rushed to learn all I could about writing. Steven King's On Writing best motivated my day-to-day rhythms. I learned the importance of daily physical exercise, daily word-count goals, and the beauty of writing to very loud rock ‘n roll. Light exercise for cognition gave me space to think and kept my energy and spirits high. I also reduced my consumption of alcohol. Maybe the write drunk, edit sober quip works for some. Not me. Every day was precious and missing one because I was not sharp was not an option.

I found the whole journey to be a complexity management process. Inhabiting the roles of researcher, writer, illustrator, and book designer meant I always had options for where to direct my energy. A walk with coffee along the San Francisco Bay, looking for sea lions, started many days. As a kind of creative hydra, I spent this time asking myself what does the book want me to do today? No matter the task, I aspired to hit two heavy creative periods each day. Mornings were my most productive time. My creative energy slumps in the afternoon, so that's when I would exercise. Sometimes I would take short naps to spring a little energy and get an extra dose of free-association time. If things were humming then I would stay up, sometimes until sunrise.

Word-count goals spurred progress. 2,000 words a day was my goal when I wrote. It was instantly obvious when I had not done the necessary preparation of reading, thinking, sketching, and outlining. It was also obvious at the end of the night when I had run out of steam. When words turned to mush, I said goodnight.

I split my desk into digital and analog workspaces. All research materials relevant to the section I was working on were at arm's length in a bookcase behind me. At the beginning they all fit. By the end, every flat surface I had was covered in stacks of books and papers. I got myself out of more than one haze by rearranging the piles of books. Colored pens, markers, index cards, book holders, and whatever mix of books I was reading at the time were stored in a small rolling cart. That way, I could wheel essential materials to the kitchen table or comfy chair whenever I got tired of my desk.

I did research by reading books in thematic bundles. For example, I read three books in one day that each explain statistics to the layperson. Across this project, I found myself developing a style of “extractive reading.” Reading for purpose, in support of a project or specific inquiry, helps focus attention. This aggression was tempered with caution. I did not read for confirmation, but genuine discovery and learning.

I took a careful approach to reading other books about data visualization. Before writing anything, I read the modern classics (Bertin, Tukey, Tufte, Cleveland, Holmes) written before 1985. This cutoff date is just before interactive computer graphics made a big splash. I read these to discover what still rang true from back then. My hunch was if it was true then and still resonates with my own practice, then it has a good shot at being timeless.

I did not review any recent data visualization books or articles until after my first draft was complete. I wanted to make sure the skeleton of the book came from my own experience and what I had discovered to be timeless. I also did not want to be too influenced by any other contemporary authors. The story had to be told in my own voice. Once the first draft was finished, I was able to turn to my colleagues to help polish and sharpen my perspective.

For books that were not about data visualization, I used a similar but more immediate process. For example, for the chapter “Encounter” I wrote everything I could without doing any research. Then I read six books on museum design, curating, and human-scale urban planning that I already had staged. Then, I returned and revised the chapter.

Here is how I processed material from research to writing. Except in the case of a couple of rare old books, I underlined and made notes directly on the page in red ink. Once the book was read I put it aside, usually for about a day. After this short gap, I re-opened the book to review the redlines. Every book I read got a page (or more) of handwritten notes in a big black Moleskine journal. I copied exact quotes, summaries, and my own reactions in color-coded handwriting into the journal. This process resulted in a hand-lettered notebook chock-full of sketches, quotes, and observations. Condensing research into a single place was useful in many ways. A sequence of different looks at the sources acted as a set of filters. They also gave me and the material time to breathe. Collating everything in one notebook fostered unexpected connections. It expedited writing as I did not have to spend lots of time fumbling between hundreds of sources. As I typed, the journal was open and in view. It is now a neat physical artifact of my experience.

While reading, I also kept a jumbo-sized index card as a book mark. There, I could write random thoughts that came to me as I read. Anything that came to me across any part of the process got written down. I found my memory generally deteriorated to becoming useless across the writing process. Externalizing any idea was essential if it was to prevail. As the book's form took shape, I would note which chapter, and later, which page number, the idea was relevant to. These cards were stacked and later processed into the draft.

I now know what other writers meant about pushing through the first draft so that the real work, editing, can begin. Writing the first draft felt like going into an empty room, my nerd cave, and summoning a wild cave bear. Then, all the work that followed was to go back into that room every day to wrestle with the bear. The more I worked with it, the more I found that it had a spirit of its own. It became my responsibility to focus its spirit so that it could sing. I found that being an author, much like any designer, is not so much about producing something out of thin air, but rather about being the motivating force behind an evolutionary process. For editing style, I devoured Steven Pinker's The Sense of Style. His mechanical breakdown of how sentences and paragraphs work was the perfect lens for this engineer-author. I used different search strategies to highlight phrases that might benefit from extra attention. Instead of hedging with fluff words (almost, apparently, nearly…), I learned to qualify where necessary. Instead of lifeless nominized verbs (-tion, -sion, -ing), I learned to resurrect dynamic verbs. Instead of invisible meta-concepts (process, level, …), I tried to include illustrative examples. I learned that intensifiers (very, highly, …) do not intensify. Very turns a true/false statement into a gradated scale. The use of margin notes was directly inspired by Robert Greene's The 48 Laws of Power. About half of my marginalia made it into the final draft. There is so much wonder out there left to explore.

After the first draft was written I prototyped a single chapter, which forced me to figure out image style, color palette, layout design, and how all of the visual elements might work together. In addition to giving me a very real design challenge, this prototype gave me something to show others. Early feedback from designers and authors helped me define the entire look of the book.

Across the rest of the process I not only workshopped the words,but also theillustrations and the book layout. Months in, I discovered that it was necessary to do all of this on my own in order to create the composition harmony across each page spread that I desired. Doing it all was equally challenging and insightful. It gave me more constraints, and more ways, of seeing every aspect of the book.

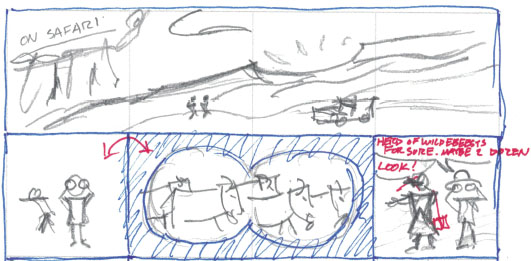

The primary color palette of Oliver Byrne's 1843 Elements of Euclid inspired the colors. The hundreds of illustrations were a joy to produce. They were all hand-drawn with markers and scanned for digital polishing. Many referenced printed digital collages, YouTube video frames, charts made with D3 and Tableau, Google Earth, and 3-D SketchUp renders. I wanted the illustrations rough enough to convey emotion, but not so rough that they distracted.

Most of the historic images I reference are manipulated in some way to better serve the story. For example, the found illustration of the Mad Hatter at a tea party was transformed into the Chapter 6 title image. I repositioned his arms, gave him the teapot, and created the stacks of cups by photographing teacups and mugs in my kitchen.

The following notes have more details about the illustrations. They now reside in a drawer in the same small room.