14 Managing Brands Over Geographic Boundaries and Market Segments

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

-

Understand the rationale for developing a global brand.

-

Outline the main advantages and disadvantages of developing a standardized global marketing program.

-

Define the strategic steps in developing a global brand positioning.

-

Describe some of the unique characteristics of brand building in developing markets like India and China.

A global marketing pioneer, KFC is now setting its sights on market leadership in China.

Source: Zheng Xianzhang/TAO Images Limited/Alamy

Preview

In earlier chapters, we’ve considered how and why marketers (1) create brand portfolios to satisfy different market segments and (2) develop brand migration strategies to attract new and retain existing customers. This chapter looks at managing brand equity in different types of market segments. We’ll pay particular attention to international issues and global branding strategies.

Specifically, we begin by considering brand management issues over regional, demographic, and cultural market segments. Next, after reviewing the basic rationale for taking brands into new international markets, we consider the broader issues in developing a global brand strategy and look at some of the pros and cons of developing a standardized global marketing program.

In the remainder of the chapter, we concentrate on specific strategic and tactical issues in building global customer-based brand equity, organized around the concept of the “Ten Commandments of Global Branding.” To illustrate these guidelines, we’ll rely on global brand pioneers such as Coca-Cola, Nestlé, and Procter & Gamble. Brand Focus 14.0 addresses branding issues in the exploding Chinese market.1

Regional Market Segments

Regionalization seems to run counter to globalization. Marketers are interested in regional marketing today, however, because mass markets are splintering, computerized sales data from supermarket scanners can reveal regional pockets of sales strengths and weaknesses, and marketing communications make possible more focused targeting of consumer groups defined along virtually any lines.

A regionalization strategy can make a brand more relevant and appealing to any one individual. One study of retail stores found that a localization strategy could boost sales by one to three percentage points, and just 10–15 percent of inventory needed to be customized to get as much as 90 percent of the benefit. Tapping into several trends, Macy’s has made its brand simultaneously more local and more national.2

Macy’s

Macy’s celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2008, a milestone for any brand. Acquisitions, notably of the May Co. for over $11 billion, created a strong national chain of 825 stores, all under the iconic Macy’s brand name. At the same time, Macy’s recognizes the value of tailoring merchandise to suit local and regional tastes. With a strategy dubbed “My Macy’s,” the goal is to have 15 percent of merchandise in stores reflect local preferences, a high percentage given the 1.5–4 million different items typically stocked in each store. Using database technology, Macy’s can determine the volume, type, and color of sweaters to sell in different stores, for example, and when to replenish inventory. For Bellevue, Washington, whose local Asian population has grown from 4 percent to 23 percent over a 20-year period, the local Macy’s added more small and extra-small sizes. The company also needed to double the size of its sock department at the store, which store staff attributed to the forgetfulness of outsiders coming to visit Microsoft’s nearby offices. With a sizable African American customer base interested in men’s fashions, the Cumberland Mall store in Atlanta doubled the space devoted to men’s hats. Combined with a number of other marketing initiatives, Macy’s has outperformed its competition in recent years. In January 2012, after a stellar holiday season, CEO Terry Lundgren observed, “We clearly saw the tangible progress of our My Macy’s localization, omnichannel integration of stores, online and mobile, and ‘MAGIC Selling’ [a customer engagement training program], which have been driving our business over the past two years.”3

Macy’s is adjusting its merchandise assortments to reflect local tastes, like expanding its hat department in hat-loving parts of Atlanta.

Source: David Walter Banks/The New York Times/Redux Pictures

Different battles are now being fought between brands in different regions of the country. Anheuser-Busch and Miller Brewing have waged a fierce battle in Texas for years, where nearly 1 in 10 beers sold in the United States is consumed. Anheuser-Busch made sizable inroads during this time through special ad campaigns, displays, and sales strategies. As one observer noted, “Texans believe it’s a whole different country down here. They don’t want you to just slap an armadillo in a TV spot.”4

Regionalization can have downsides. Marketing efficiency may suffer and costs may rise with regional marketing. Moreover, regional campaigns may force local producers to become more competitive or blur a brand’s national identity. The upside, however, is that marketing can have a stronger impact.

Other Demographic and Cultural Segments

Any market segment—however we define it—may be a candidate for a specialized marketing and branding program. For example, demographic dimensions such as age, income, gender, and race—as well as psychographic considerations—often are related to more fundamental differences in shopping behaviors or attitudes about brands. These differences can often serve as the rationale for a separate branding and marketing program. The decision ultimately rests on the costs and benefits of customized marketing efforts versus those of a less targeted focus.

For example, Chapter 13 described how important it is for marketers to consider age segments, and how younger consumers can be brought into the consumer franchise. Because of increased consumer mobility, better communication via social media and mobile phones, and expanding transnational entertainment options, lifestyles are fast becoming more similar across countries within sociodemographic segments, than they are within countries across sociodemographic segments. A teenager in Paris may have more in common with a teenager in London, New York, Sydney, or almost any other major city in the world than with his or her own parents. This younger generation may be more easily influenced by trends and broad cultural movements fueled by worldwide exposure to movies, television, and other media than ever before. One result is that brands able to tap into the global sensibilities of the youth market may be better prepared to adopt a standardized branding program and marketing strategy. Unilever uses a standard approach to market its Axe Body Spray globally based on sex appeal.

Marketers are also considering how various ethnic, racial, or cultural groups may require different marketing programs. In 2010, Hispanics accounted for 50.5 million of the 308 million people in the United States and about $1 trillion in annual purchasing power.5 Established television networks such as Univision and Telemundo and targeted radio, newspapers, and magazines help marketers reach Hispanics with ads. Active online, the Hispanic market also has a higher smartphone penetration than the general population.6

Various firms have created specialized marketing programs with different products, advertising, promotions, and so on to better reach and persuade this market. Olive Garden Italian Restaurant chain spends 10 percent of its $150 million overall ad budget on Hispanic market television. Southwest Airlines communicates in “Spanglish”—a mixture of Spanish and English—in some ads. JC Penney’s Hispanic team is made up of marketing, merchandising, planning, real estate, and store operations. The company may stock smaller sizes in stores with larger Hispanic customer bases and observe Mexican holidays (Mother’s Day is on a different day than in the United States, for instance).7

The Asian population is also growing faster than the total population and is comparatively younger and better educated. Asian buying power is expected to grow by 42 percent in the coming years, from $544 billion in 2010 to $775 billion in 2015.8 Bank of America prospered by targeting Asians in San Francisco with separate TV campaigns aimed at Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese customers. Branding Brief 14-1 describes marketing efforts to build brand equity with African Americans.

Marketing critics say that some consumers may not like being targeted on the basis of their being different, since that only reinforces their image as outsiders or a minority. Moreover, consumers not in the targeted segment may feel alienated or distanced from the company and brand as a result.9 Companies like Ford, McDonald’s and Procter & Gamble that sell to a broad range of consumers are embracing diverse racial and ethnic markets in a natural, organic way, and they are seeing sales spikes among minority groups. In a different strategy, Burger King and Home Depot consolidated all their advertising with their general market agencies, believing there was no need to have separate agencies specializing in targeting particular minority groups; these consumers were being adequately included in their deliberately inclusive general market campaigns.10

Rationale for Going International

A number of well-known global brands have derived much of their sales and profits from non-domestic markets for decades, including Coca-Cola, Shell, Bayer, Rolex, Marlboro, Pampers, and Mercedes-Benz, to name a few. Apple computers, L’Oréal cosmetics, and Nescafé instant coffee have become fixtures on the global landscape. Their successes are among the forces that have encouraged many firms to market their brands internationally, including the following:

-

Perception of slow growth and increased competition in domestic markets

-

Belief in enhanced overseas growth and profit opportunities

-

Desire to reduce costs from economies of scale

-

Need to diversify risk

-

Recognition of global mobility of customers

In more product categories, the ability to establish a global profile is becoming a prerequisite for success. For example, in luxury goods such as jewelry, watches, and handbags, where the addressable market is a relatively small percentage of the global market, a global profile is necessary to grow profitably. Ideally, the marketing program for a global brand consists of one product formulation, one package design, one advertising program, one pricing schedule, one distribution plan, and so on that would prove the most effective and efficient option for every country in which the brand was sold. Unfortunately, such a uniformly optimal strategy is rarely possible. Consider how the Oreo brand has evolved globally.

Oreo

In launching its Oreo brand of cookies worldwide, Kraft chose to adopt a consistent global positioning, “Milk’s Favorite Cookie.” Although not necessarily highly relevant in all countries, it did reinforce generally desirable associations like nurturing, caring, and health. To help ensure global understanding, Kraft created a brand book with a CD in an Oreo-shaped box that summarized brand management fundamentals—what needed to be common across countries, what could be changed, and what could not. In time, differences emerged across markets. In China, the original cookie is less sweet than in the United States and has different fillings, such as green tea ice cream, grape–peach, mango–orange, and raspberry–strawberry. In an example of reverse innovation, Kraft has actually successfully introduced some of these Oreo flavors into other countries. Oreo is also making a big push in India, where it is just entering the market and facing stiff competition from major local brands there, such as Parle, Britannia, and Sunfeast. Launch ads reflected Oreo’s updated global positioning based on moments of togetherness and featured a father and son in the “twist, lick, dunk” ritual. Social media has Indian parents sign an “Oreo Togetherness Pledge” promising to spend more quality time with their children. An Oreo Togetherness Bus roams the country providing a platform for parents and children to catch fun family moments. Thanks to international marketing acumen, Oreo now is a $2 billion global brand for Kraft, with 23 million members in its Facebook community.11

Adapting its iconic Oreo cookie to reflect local tastes and culture, Kraft has found much success in developing markets like China and India.

Source: AP Photo/Imaginechina

Next, let’s consider the advantages and disadvantages of creating globally standardized marketing programs for brands.

Advantages of Global Marketing Programs

A number of potential advantages attach to a global marketing program (see Figure 14-1).12 In general, the less it varies from country to country, the more these advantages will be realized.

Economies of Scale in Production and Distribution

From a supply-side or cost perspective, the primary advantages of a global marketing program are the manufacturing efficiencies and lower costs that derive from higher volumes in production and distribution. The more that strong experience curve effects exist—driving down the cost of making and marketing a product with increases in production—the more economies of scale in production and distribution from a standardized global marketing program will prevail.

Economies of scale in production and distribution

Lower marketing costs

Power and scope

Consistency in brand image

Ability to leverage good ideas quickly and efficiently

Uniformity of marketing practices

Figure 14-1 Advantages of Global Marketing Programs

Lower Marketing Costs

Another set of cost advantages arises from uniformity in packaging, advertising, promotion, and other marketing communication activities. The more uniform, the greater the potential savings. A global corporate branding strategy such as Sony’s is perhaps the most efficient means of spreading marketing costs across both products and countries. Branding experts maintain that using one name can save a business tens of millions of dollars a year in marketing costs.13

As Chapter 13 noted, L’Oréal has pursued an aggressive global growth strategy, prompting one business writer to christen the company “the United Nations of beauty.” Its Maybelline line is the best-selling brand in many Asian markets, while eastern Europeans prefer L’Oréal’s French brands, and African immigrants in Europe go for the U.S. brand Dark and Lovely. L’Oréal ensures its business remains sound on a local level by establishing national divisions. Because Brazilian women traditionally bought their cosmetics from door-to-door sales reps, the company introduced personal beauty advisers at department stores there. As the one-time head of L’Oréal’s head of luxury products said, “You have to be local and as strong as the best locals but backed by an international image and strategy.”14

Power and Scope

A global brand profile can communicate credibility.15 Consumers may believe that selling in many diverse markets is an indication that a manufacturer has gained much expertise and acceptance, meaning the product is high quality and convenient to use. An admired global brand can also signal social status and prestige.16 Avis assures its customers that they can receive the same high-quality car rental service anywhere in the world, further reinforcing a key benefit promise embodied in its slogan, “We Try Harder.”

Consistency in Brand Image

Maintaining a common marketing platform all over the world helps maintain the consistency of brand and company image; this is particularly important where customers move often or media exposure transmits images across national boundaries. Gillette sells “functional superiority” and “an appreciation of human character and aspirations” with its razors and blades brands worldwide. Services often desire to convey a uniform image due to consumer movements. For example, American Express communicates the prestige and utility of its card worldwide.

Ability to Leverage Good Ideas Quickly and Efficiently

One global marketer notes that globalization can increase sustainability and “facilitate continued development of core competencies with the organization . . . in manufacturing, in R&D, in marketing and sales, and in less talked about areas such as competitive intelligence . . . all of which enhance the company’s ability to compete.”17 Not having to develop strictly local versions speeds a brand’s market entry. Marketers can leverage good ideas across markets as long as the right knowledge transfer systems are put into place. IBM has a Web-based communications tool that provides instant multimedia interaction to connect marketers. MasterCard’s corporate marketing group helps facilitate information and best practices across the organization.18

Uniformity of Marketing Practices

Finally, a standardized global marketing program may simplify coordination and provide greater control of communications in different countries. By keeping the core of the marketing program constant, marketers can pay greater attention to making refinements across markets and over time to improve its effectiveness. Chapter 3 described the rationale for the MasterCard “Priceless” campaign. Here is how it became a global blockbuster.

Mastercard

MasterCard quickly evolved its successful “Priceless” campaign, launched in 1996, into a “worldwide platform.” By 1998, the tagline, “The best things in life are free. For everything else, there’s MasterCard” was in use in over 30 countries. Some ads’ premises were universal enough to work as is, with only language translation, such as the “Zipper” ad, in which the priceless moment is a man realizing his zipper is down before anyone else does. In other cases, a locally relevant premise was used instead, with the same tagline. “Every culture has those meaningful moments, which is why we’ve been able to globalize the campaign,” stated a creative director for McCann Erickson, which developed the campaign. Sponsorships for sports with international appeal, such as World Cup soccer and Formula 1 racing, also increased the campaign’s ability to connect with a worldwide audience. The campaign was credited with lifting brand awareness in a number of nations, driving card sales, and enabling MasterCard to take market share from Visa. Over 15 years later, the campaign is still running strong.19

Disadvantages of Global Marketing Programs

Perhaps the most compelling disadvantage of standardized global marketing programs is that they often ignore fundamental differences of various kinds across countries and cultures (see Figure 14.2). Critics claim that designing one program for all possible markets results in unimaginative and ineffective strategies geared to the lowest common denominator. Possible differences across countries come in a host of forms, as we discuss next.

Differences in Consumer Needs, Wants, and Usage Patterns for Products

Differences in cultural values, economic development, and other factors across nationalities lead customers to behave very differently. For example, the per capita consumption of alcoholic beverages varies dramatically from country to country: in liters consumed per capita annually, the Czech Republic (8.51) and Ireland (7.04) drink the most beer; France (8.14) and Portugal (6.65) drink the most wine; and South Korea (9.57) and Russia (6.88) drink the most distilled spirits.20

Product strategies that work in one country may not work in another. Tupperware, which makes the bulk of its annual sales overseas—57 percent from emerging markets—needed to adjust its products to satisfy different consumer behavior. In India, a plastic container paired with a spoon becomes a “masala keeper” for spices. In Korea, stain-resistant canisters are ideal for kimchi fermentation. Larger boxes work as safe, airtight “kimono keepers” in Japan. In France, its more expensive cookware line does much better than in the United States, where customers buy more plastic containers. Tupperware parties in France feature cooking lessons more than selling. India has followed suit, introducing the stylish Ultimo line of kitchenware.21

Differences in Consumer Response to Branding Elements

Linguistic differences across countries can twist or change the meaning of a brand name. Sound systems that differ across dialects can make a word problematic in one country but not another. Cultural context is key. Customers may actually respond well to a name with potentially problematic associations. The questions are how widespread the association is, how immediate it is, and how problematic it actually would be.

Well-known brand consultancy Lexicon employs linguists to help make these assessments for clients.22 The agency has uncovered names that would have been a sexual insult in

Differences in consumer needs, wants, and usage patterns for products

Differences in consumer response to branding elements

Differences in consumer response to marketing mix elements

Differences in brand and product development and the competitive environment

Differences in the legal environment

Differences in marketing institutions

Differences in administrative procedures

Figure 14-2 Disadvantages of Global Marketing Programs

Tupperware emphasizes different products and marketing strategies in different parts of the world.

Sources: Tupperware party in Indonesia. Courtesy of Tupperware Brands

Colombian Spanish, been sacrilegious in Hindi, conveyed impotence in Japanese, and translated as “prostitute” in Hebrew. GM went ahead and used the LaCrosse model name for its Buick line in Canada so it could leverage its U.S. advertising, even though the word was slang for masturbation in French-speaking Quebec. The hope was that its more formal English meaning as a well-known sport would dominate there.23

Differences in Consumer Responses to Marketing Mix Elements

Consumers in different parts of the world feel differently about marketing activity.24 U.S. consumers tend to be fairly cynical toward advertising, whereas Japanese view it much more positively. Differences also exist in advertising style: Japanese ads tend to be softer and more abstract in tone, whereas U.S. ads are often richer in product information.

Price sensitivity, promotion responsiveness, sponsorship support, and other activities all may differ by country, and these differences can motivate differences in consumer behavior and decision making. In a comparative study of brand purchase intentions, U.S. consumers were twice as likely to be affected by their product beliefs and attitudes toward the brand itself, whereas Koreans were eight times more likely to be influenced by social normative beliefs and what they felt others would think about the purchase.25

Finding a brand name without some kind of negative connotations in a particular language can be challenging, as Buick LaCrosse found in Canada.

Source: AP Photo/Carlos Osorio

Brand |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Strength |

USA |

UK |

Germany |

France |

Brazil |

China |

Rank |

2011 |

2011 |

2009 |

2009 |

2011 |

2011 |

1 |

United States |

Germany |

France |

Rede Globo |

Chun Jie Wan Hui |

|

2 |

Pixar |

United Kingdom |

IKEA |

Copa do Mundo |

Q-Zone |

|

3 |

Disney |

Microsoft |

IKEA |

Arte |

Fantȥstico |

KFC |

4 |

Dyson |

Die Olympischen |

Canal + |

SBT |

Colgate |

|

Spiele |

||||||

5 |

Discovery Channel |

eBay |

adidas |

Globo RepɃrter |

||

6 |

U.S. Marines |

Apple |

eBay |

Coca-Cola |

Jornal Nacional |

Baidu |

7 |

Microsoft |

Nintendo Wii |

Windows |

M6 |

Rede Record |

China Mobile |

8 |

National Geographic |

LEGO |

HȨagen-Dazs |

Nestlȳ |

Xin Wen Lian Bo |

|

9 |

DreamWorks (SKG) |

IKEA |

BMW |

Nutella |

Coca-Cola |

Apple (Computer) |

10 |

Channel 4 |

Aldi |

Nintendo Wii |

Brastemp |

Nokia |

|

Figure 14-3 Global Brand Rankings (includes products, people, and countries)

Source: BrandAsset Consulting. Used with permission.

Differences in Brand and Product Development and the Competitive Environment

Products may be at different stages of their life cycle in different countries. Moreover, the perceptions and positions of particular brands may also differ considerably across countries. Figure 14-3 shows the results of a comprehensive study of leading brands (of all kinds, including people and country brands) in different parts of the world according to the BrandAsset Valuator measurement technique (see Brand Focus 9.0). Relatively few brands appear on all the lists, suggesting that, if nothing else, consumer perceptions of even top brands can vary significantly by geographic region.

The nature of competition may also differ. Europeans tend to see more competitors because shipping products across borders is easy. Germany’s Mittelstand—small and mid-sized companies with fewer than 500 people—employ more than 70 percent of German workers and contribute roughly half of the country’s GDP. They are especially formidable competitors. Blending high technology with a focus on quality, they weathered the recession well in Europe’s largest market (82 million people).26

Differences in the Legal Environment

One of the challenges in developing a global ad campaign is the maze of constantly changing legal restrictions from country to country. At one time, laws in Venezuela, Canada, and Australia stipulated that commercials had to be physically produced in the native country. Canada banned prescription drug advertising on television. Poland required commercial lyrics to be sung in Polish. Sweden prohibited advertising to children. Malaysia did not allow lawyers or law firms to advertise. Advertising restrictions have been placed on the use of children in commercials in Austria, comparative ads in Singapore, and product placement on public television channels in Germany. Although some of these laws have been challenged or are being relaxed, numerous legal differences still exist.

Differences in Marketing Institutions

Channels of distribution, retail practices, media availability, and media costs all may vary significantly from country to country, making implementation of the same marketing strategy difficult. Foreign companies struggled for years to break into Japan’s rigid distribution system that locks out many foreign goods. The penetration of cable television, cell phones, supermarkets, and so on may also vary considerably, especially in developing countries.

Differences in Administrative Procedures

In practice, it may be difficult to achieve the control necessary to implement a standardized global marketing program. Local offices may resist having their autonomy threatened. Local managers may suffer from the “not invented here” syndrome and raise objections—rightly or wrongly—that the global marketing program misses some key dimension of the local market. Local managers who feel their autonomy has been reduced may lose motivation and feel doomed to failure.

Global Brand Strategy

With that background, let’s turn to some basic strategic issues in global branding. The contention of this chapter is that in building brand equity, we often must create different marketing programs to satisfy different market segments. Therefore we must:

-

Identify differences in consumer behavior—how consumers purchase and use products and what they know and feel about brands—in each market.

-

Adjust the branding program accordingly through the choice of brand elements, the nature of the actual marketing program and activities, and the leveraging of secondary associations.

Note that the third way to build global brand equity, leveraging secondary brand associations, is probably the most likely to require change across countries because the entities linked to a brand may take on very different meanings in different countries. For example, U.S. companies such as Coca-Cola, Levi Strauss, and Nike traditionally gained an important source of equity in going overseas by virtue of their U.S. heritage, which is not as much of an issue or asset in their domestic market. Harley-Davidson has aggressively marketed its classic U.S. image—customized for different cultures—to generate about 30 percent of its sales from abroad.27 Brands large and small can try to tap into their geographical roots. Gosling’s Black Seal Bermuda black rum uses its Caribbean heritage and its trademarked ingredient in the “dark and stormy” cocktail in its efforts to build a global brand.28

Understanding how consumers actually form their impressions of country of origin and update their brand knowledge can be challenging.29 The design, manufacture, assembly, distribution, and marketing of products often involve several countries. Apple’s iPhone is designed and owned by a U.S. company and assembled and shipped from China from parts produced largely in several Asian and European countries.30

Global Brand Equity

As we explained in Chapter 2, to build brand resonance, marketers must (1) establish breadth and depth of brand awareness; (2) create points-of-parity and points-of-difference; (3) elicit positive, accessible brand responses; and (4) forge intense, active brand relationships. Achieving these four steps, in turn, requires establishing six core brand building blocks: brand salience, brand performance, brand imagery, brand judgments, brand feelings, and brand resonance. In each and every market in which marketers sell the brand, they must consider how to achieve these steps and create these building blocks. Some of the issues that come into play are discussed in the following subsections.

Black Seal Rum leverages its Bermuda heritage to build its brand equity in overseas markets.

Source: AP Photo/PRNewsFoto/Gosling’s Rum of Bermuda

Creating Brand Salience

It is rare that a product will roll out in new markets the same way it did in the home market. Often, product introductions in the domestic market are sequential, stretched out over a longer period of time than the nearly simultaneous introductions that occur overseas.

Nivea

Nivea’s flagship product in its European home market has been its category leader, Nivea Creme. Although the company had introduced other skin care and personal care products, Nivea Creme had the most history and heritage and reflected many core brand values. In Asia, however, for cultural and climate reasons, the creme product was less well received, and the facial skin care sub-brand, Nivea Visage, and creme line extension, Nivea Soft, were of greater strategic and marketing importance. Because these two product brands have slightly different images than the Creme brand, an important issue was the impact on consumers’ collective impressions of Nivea. A strong initial emphasis on Nivea for Men in North America raised similar questions.

Different orders of introduction can profoundly affect consumer perceptions about what products the brand offers, the benefits supplied, and the needs satisfied. Thus, we need to examine the breadth and depth of recall to ensure that the proper brand salience and meaning exist.

Crafting Brand Image

If the product does not vary appreciably across markets, basic brand performance associations may not need to be that different. Brand imagery associations, on the other hand, may be quite different, and one challenge in global marketing is to meaningfully refine the brand image across diverse markets. History and heritage, which may be rich and a strong competitive advantage in the home market, may be virtually nonexistent in a new market. A desirable brand personality in one market may be less desirable in another. Nike’s competitive, aggressive user imagery proved a detriment in its introduction into European markets in the early 1990s. The company achieved greater success when it dialed down its image somewhat and emphasized team concepts more.

Eliciting Brand Responses

Brand judgments must be positive in new markets—consumers must find the brand to be of good quality, credible, worthy of consideration, and superior. Crafting the right brand image will help accomplish these outcomes. One of the challenges in global marketing, however, is creating the proper balance and type of emotional responses and brand feelings. Blending inner (enduring and private) and outer (immediate experiential) emotions can be difficult, given cultural differences across markets.

Cultivating Resonance

Finally, achieving brand resonance in new markets means that consumers must have sufficient opportunities and incentives to buy and use the product, interact with other consumers and the company itself, and actively learn and experience the brand and its marketing. Clearly, interactive, online marketing can be advantageous here, as long as it can be accessible and relevant anywhere in the world. Nevertheless, digital efforts cannot completely replace grassroots marketing efforts that help connect the consumer with the brand. Simply exporting marketing programs, even with some adjustments, may be insufficient because consumers may be too much at “arm’s length.” As a result, they may not be able to develop the intense, active loyalty that characterizes brand resonance.

Global Brand Positioning

To best capture differences in consumer behavior, and to guide our efforts in revising the marketing program, we must revisit the brand positioning in each market. Recall that brand positioning means creating mental maps, defining core brand associations, identifying points-of-parity and points-of-difference, and crafting a band mantra. In developing a global brand positioning, we need to answer three key sets of questions:

-

How valid is the mental map in the new market? How appropriate is the positioning? What is the existing level of awareness? How valuable are the core brand associations, points-of-parity, and points-of-difference?

-

What changes should we make to the positioning? Do we need to create any new associations? Should we not recreate any existing associations? Should we modify any existing associations?

-

How should we create this new mental map? Can we still use the same marketing activities? What changes should we make? What new marketing activities are necessary?

Because the brand is often at an earlier stage of development when going abroad, we often must first establish awareness and key points-of-parity. Then we can consider additional competitive considerations. In effect, we need to define a hierarchy of brand associations in the global context that defines which associations we want consumers in all countries to hold, and which we want consumers only in certain countries to have. We have to determine how to create these associations in different markets to account for different consumer perceptions, tastes, and environments. Thus, we must be attuned to similarities and differences across markets.

As this discussion suggests, although firms are increasingly adopting an international marketing perspective to capitalize on market opportunities, a number of possible pitfalls exist. Before providing some specific tactical guidelines as to how to build global customer-based brand equity, we first turn to two fundamentally important contrasts in global branding: standardization versus customization, and developing versus developed markets.

Standardization Versus Customization

The most fundamental issue in developing a global marketing program is the extent to which the marketing program should be standardized across countries, because this decision has such a deep impact on marketing structure and processes. Perhaps the biggest proponent of standardization was the legendary Harvard professor Ted Levitt.

In a controversial 1983 article, Levitt argued that companies needed to learn to operate as if the world were one large market, ignoring superficial regional and national differences.31 According to Levitt, because the world was shrinking—due to leaps in technology, communication, and so forth—well-managed companies should shift their emphasis from customizing items to offering globally standardized products that are advanced, functional, reliable, and low-priced for all. Levitt’s strong position elicited an equally strong response. One ad executive commented, “There are about two products that lend themselves to global marketing—and one of them is Coca-Cola.” Other critics pointed out that even Coca-Cola did not standardize its marketing—as Branding Brief 14-2 illustrates—and noted the lack of standardization in other leading global brands, such as McDonald’s and Marlboro.

The experiences of these top marketers have been shared by others who found out—in many cases, the hard way—that differences in consumer behavior still prevail across countries. Many firms have been forced to tailor products and marketing programs to different national markets as a result. In short, it’s difficult to identify any one company applying the global marketing concept in the strict sense—by selling the same brand exactly the same way everywhere.

Standardization and Customization

Increasingly, marketers are blending global objectives with local or regional concerns. From these perspectives, transferring products across borders may mean consistent positioning for the brand, but not necessarily the same brand name and marketing program in each market. Similarly, packaging may have the same overall look but be tailored as required to fit the local populace and market needs. For example, Danone’s kids’ yogurts are sold under a variety of names—Danonino, Danoontje, Danimals—in over 120 countries, while a general manager leads a central team that coordinates and oversees the local marketing efforts.32

In short, centralized marketing strategies that preserve local customs and traditions can be a boon for products sold in more than one country—even in diverse cultures. Fortunately, firms have improved their capabilities to tailor products and programs to local conditions. Flexible manufacturing technology has decreased the concentration of activities, and advances in information systems and telecommunications have allowed increased coordination.

Domino’s Pizza tried to maintain the same delivery system everywhere but had to adapt the model to local customs in launching its brand overseas. In Britain, customers thought anybody

knocking on the door was rude; in Kuwait, the delivery was just as likely to be made to a limousine as to a house; and in Japan, houses were not numbered sequentially, making finding a particular address difficult.

Although Heineken is seen as an everyday brand in the Netherlands, it is considered a “top-shelf” brand almost everywhere else. A case of the beer costs almost twice as much in the United States as the most popular U.S. brand, Budweiser.33 For a long time, Heineken’s slogan in the United Kingdom and other countries—”Heineken Refreshes the Parts Other Beers Can’t Reach”—was different from its U.S. positioning.

As these examples suggest, top brands adapt their marketing programs in different parts of the world. We next review the four major elements of a marketing program—product, communications, distribution, and pricing strategies—in terms of adaptation issues.

Product Strategy

One reason so many companies ran into trouble initially going overseas is that they unknowingly—or perhaps even deliberately—overlooked differences in consumer behavior. Because of the relative expense and sometimes unsophisticated nature of the marketing

research industry in smaller markets, many companies chose to forgo basic consumer research and put products on the shelf to see what would happen. As a result, they sometimes became aware of consumer differences only after the fact. To avoid these types of mistakes, marketers may need to conduct research into local markets.

In many cases, however, marketing research reveals that product differences are not justified for certain countries. At one time, Palmolive soap was sold globally with 22 different fragrances, 17 packages, nine shapes, and numerous positionings. After conducting marketing analyses to reap the benefits of global marketing, the company chose to employ just seven fragrances, one core packaging design, and three main shapes, all executed around two related positionings (one for developing markets and one for developed markets).34 Branding Brief 14-3 describes how UPS has successfully adapted its service for the European market.

From a corporate perspective, one obvious solution to the trade-off between global and local brands is to sell both types of brands as part of the brand portfolio in a category. Even companies that have succeeded with global brands maintain that standardized international marketing programs work with only some products, in some places, and at some times, and will never totally replace brands and ads with local appeal.35 Thus, despite the trend toward globalization, it seems that there will always be opportunities for good local brands.

Communication Strategy

Advertising is one area of marketing communications in which many firms face challenges internationally. Although the brand positioning may be the same in different countries, creative strategies in advertising may have to differ to some degree. One highly successful recent global brand campaign promoted Johnnie Walker Scotch.

Johnnie Walker

The top Scotch brand of Diageo—the largest multinational wine and spirits company—has its roots in nineteenth-century Scotland. In 1908, the brand itself was launched, including the iconic logo of a cane-wielding man clad in boots and a top hat striding forward, in honor of the founder John, or “Johnnie,” Walker. Every type of Johnnie Walker Scotch has a label color to denote type and quality and signify usage occasion. More recently, at about the turn of the century, the brand experienced a downturn, and sales dropped almost 10 percent. A new ad agency determined that the brand needed to better establish its “World Cup–level” icon status. The insight to achieve that goal was that a new generation of men shared a common desire to move forward and improve themselves in some way. Renowned ad agency BBH reversed the logo image so the “Striding Man” would be moving from left to right, to signify personal progress. With a slogan, “Keep Walking,” a campaign was launched in 120 countries via 30 TV ads, 150 print ads, radio ads, Web sites, sponsorships, internal awards, and a cause program to support the brand’s purpose. A five-minute film, The Man Who Walked Around the World, featured actor Robert Carlyle cleverly outlining Johnnie Walker’s brand history in one continuous, flowing shot. The global brand concept was creatively applied in different markets to make it locally recognizable and relevant. In Africa, a key target for brand growth, Johnnie Walker is put forth as a symbol of personal success. Billboards and magazine ads there feature champion Ethiopian runner Haile Gebrselassie “running for gold.”36

Diageo used its “Keep Walking” marketing campaign all over the world to support its Johnnie Walker brand.

Source: AP Photo/Andrew Milligan/PA Wire

Different countries can be more or less receptive to different creative styles. For example, humor is more common in U.S. and UK ads than, say, in German ads. European countries such as France and Italy are more tolerant of sex appeal and nudity in advertising.37 The penetration of satellite and cable TV has expanded broadcast media options, making it easier to simultaneously air the same TV commercial in many different countries. U.S. cable networks such as CNN, MTV, and the Cartoon Network, and other networks such as Sky TV in Commonwealth countries and Star TV in Asia have increased advertisers’ global reach.

In terms of print, Fortune, Time, Newsweek, and other magazines have printed foreign editions in English for years. Other publishers have also added local-language editions by licensing

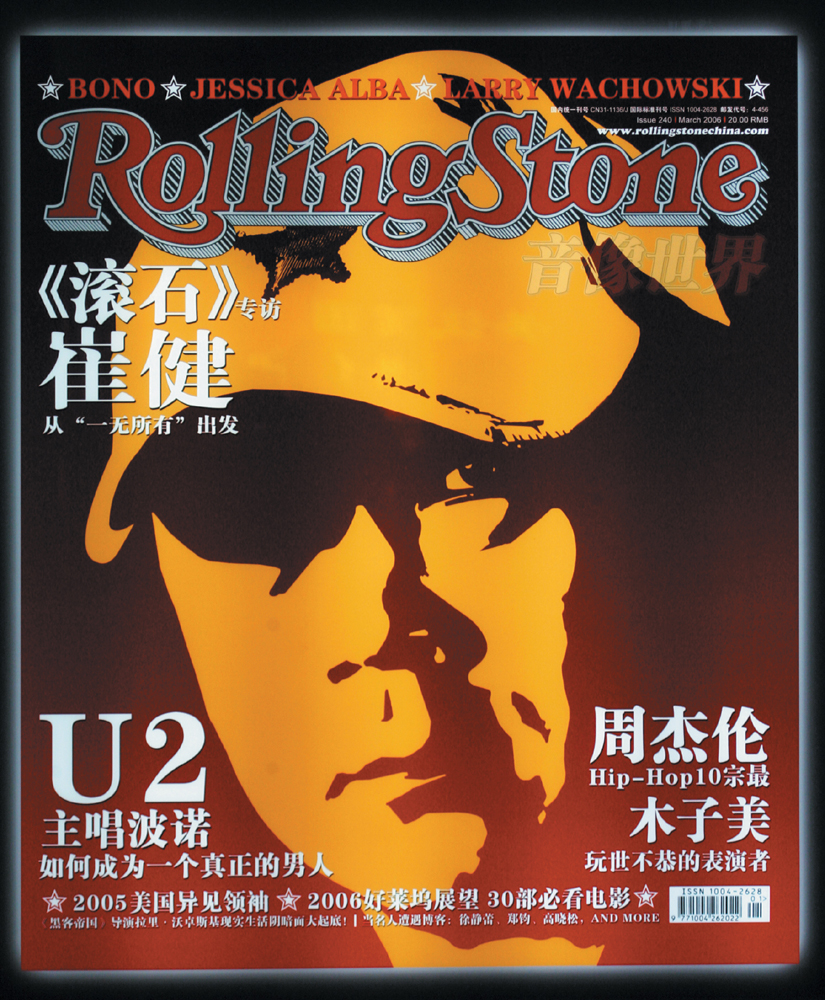

Like many magazine publications, Rolling Stone produces local-language editions for overseas markets like China.

Source: Dong Ng/EyePress News/Newscom

their trademarks to local companies, entering into joint ventures, or creating wholly owned subsidiaries. Rolling Stone has 20 international editions outside the United States; Maxim has 27 overseas editions; and Elle has 42 editions targeting the same demographic group but tailored to the country where each is published.

Each country has its own unique media challenges and opportunities. When Colgate- Palmolive decided to further penetrate the market of the 630 million or so people who lived in rural India, the company had to overcome the fact that more than half of all Indian villagers are illiterate and only one-third live in households with television sets. Its solution was to create half-hour infomercials carried through the countryside in video vans.38 To sell Tampax tampons in Mexico, Procter & Gamble created in-home informational gatherings or “bonding sessions” akin to Tupperware parties led by company-designated counselors. Although about 70 percent of women in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe used tampons, just 2 percent of women in most of Latin America did. To overcome cultural inhibitors, P&G developed its unorthodox approach.39

Sponsorship programs have a long tradition in many countries outside the United States because of a historical lack of advertising media there. Increasingly, marketers can execute sponsorship on a global basis. Entertainment and sports sponsorships can be an especially effective way to reach a younger audience.

Distribution Strategy

Channels present challenges to many firms because there are few global retailers, especially supermarkets and grocery stores, although some progress has been made with Germany’s Aldi and France’s Carrefour. Established British retailers Sainsbury, Tesco, and Marks and Spencer have all struggled to enter the U.S. market. The common English language may actually have been a barrier—assumptions were made about consumers that didn’t hold true on the other side of the Atlantic. In developing its Fresh & Easy store concept for California, Tesco found that U.S. shoppers liked to pick up and touch their fruit and vegetables and stock up with more frozen food than their British customers.40

Lacking many global retail powerhouses, companies often differ in their approach to distribution, and the results can be dramatic. Coca-Cola’s intensive deployment of vending machines in Japan was a key to success in that market. From 1981 to 1993, Coca-Cola invested over $3 billion internationally in infrastructure and marketing. PepsiCo, on the other hand, sold off some of its bottling investments during this time. Despite investing in expensive ad campaigns and diversifying into restaurants and snack foods, PepsiCo saw its global fortunes sag relative to Coca-Cola and has renewed its efforts in the years since.

As in domestic markets, firms will often want to blend push and pull strategies internationally to build brand equity. Sometimes companies mistakenly adapt strategies that were critical factors to success, only to discover that they erode the brand’s competitive advantage.

Dell

Dell Computer initially abandoned its direct distribution strategy in Europe and instead decided to establish a traditional retailer network through existing channels. The end result was a paltry 2.5 percent market share, and the company lost money for the first time ever in 1994. Ignoring critics who claimed that a direct distribution model would never work in Europe, Dell revamped its direct approach and relaunched its personal computer line with a new management team to execute the direct model the company had pioneered in the United States. Between 1999 and 2004, Dell’s sales in Europe grew at an average rate of 19 percent annually, substantially outpacing other competitors in the industry. Later in the decade, however, sales slumped as the PC market stagnated all over the world. Dell now must reinvent its product strategy in Europe and elsewhere, much as it did its distribution strategy so many years before.41

Pricing Strategy

When it comes to designing a global pricing strategy, the value-pricing principle from Chapter 5 still generally applies. Marketers need to understand in each country what consumer perceptions of the value of the brand are, their willingness to pay, and their elasticities with respect to price changes. Sometimes differences in these considerations permit differences in pricing strategies. Brands such as Levi’s, Heineken, and Perrier have been able to command a much higher price outside their domestic market because in other countries they have a distinctly different brand image—and thus sources of brand equity—that consumers value. Differences in distribution structures, competitive positions, and tax and exchange rates also may justify price differences.

But setting drastically different prices across countries can be difficult.42 Pressures for international price alignment have arisen, in part because of the increasing numbers of legitimate imports and exports and the ability of retailers and suppliers to exploit price differences through “gray imports” across borders. This problem is especially acute in Europe, where price differences are often large (prices of identical car models may vary by 30–40 percent) and ample opportunity exists to ship or shop across national boundaries.

Hermann Simon, a German expert on pricing, recommends creating an international “price corridor” that takes into account both the inherent differences between countries and alignment pressures. Specifically, the corridor is calculated by company headquarters and its country subsidiaries by considering market data for the individual countries, price elasticities in the countries, parallel imports resulting from price differentials, currency exchange rates, costs in countries and arbitrage costs between them, and data on competition and distribution. No country is then allowed to set its price outside the corridor: countries with lower prices have to raise them, and countries with higher prices have to lower them. Another possible strategy suggested by Simon is to introduce different brands in high-price, high-income countries and in low-price, low-income countries, depending on the relative cost trade-offs of standardization versus customization.43

In Asia, many U.S. brands command hefty premiums over inferior home-grown competitors because consumers in these countries strongly associate the United States with high-quality consumer products. In assessing the viability of Asian markets, marketers look at average income but also consider the distribution of incomes, because the consumer population is so large. For example, although the average annual income in India may be less than $1,000, some 300 million people can still afford the same types of products that might be sold to middle-class Europeans. In China, Gillette introduced Oral-B toothbrushes at 90 cents even though locally produced toothbrushes sold at 19 cents. Gillette’s reasoning was that even if it only gained 10 percent of the Chinese market, it still would sell more toothbrushes there than it is currently selling in the U.S. market.

Developing versus Developed Markets

Perhaps the most basic distinction we make between the countries that global brands enter is whether they are developing or have developed markets. Some of the most important developing markets are captured by the acronym BRICS (for Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). To that list, many marketing experts would add Indonesia. Some experts also refer to the five Rs of currency in developing markets: the Brazilian real, the Russian ruble, the Indian rupee, the Chinese renminbi, and the Indonesian rupiah.44 These countries are considered developing in that they do not yet have the infrastructure, institutions, and other features that characterize more fully developed economies in North America and Western Europe, for example. Yet they are among the largest and fastest-growing and have received much attention from companies all over the world.

Differences in consumer behavior, marketing infrastructure, competitive frame of reference, and so on are so profoundly different among developing markets, though, that distinct marketing programs are often needed for each. Often the product category itself may not be well developed, so the marketing program must operate at a very fundamental level. Consider how these firms successfully attacked the Indian market.

Winning in India

Although some global brands have struggled entering the Indian market, others have succeeded by better understanding Indian consumers and tailoring their offerings accordingly. Hyundai became India’s second-largest carmaker by offering small, affordable, and fuel-efficient cars such as the $7,000 Santro. Nokia earned 58 percent market share by selling models specially made for the Indian market, such as its 1100 phone, which features a flashlight. Pepsi earned 24 percent market share in part because it was the first Western cola to feature Indian megacelebrities as spokespeople, including cricketer Sachin Tendulkar and actor Shahrukh Khan. LG outpaced competitors Whirlpool and Haier to $1 billion in annual sales by offering refrigerators and air conditioners that stood up better to the temperature extremes and power surges that characterize rural India. As the Indian market continues to grow and mature, catering to local tastes will become even more important for global brands seeking to compete there.45

Heinz drew 20 percent of its corporate revenues from emerging markets in 2011—versus less than 5 percent just a few years before that—with a target of 30 percent by 2015. The company adheres to a “Three As” model for its emerging markets strategy and even put it on the cover of its annual report:46

-

Applicability—Product must suit local culture. Heinz ketchup has a slightly sweet taste in the United States, but in certain European countries, it is available in hot, Mexican, and curry flavors. In the Philippines, it includes bananas as an ingredient. Ketchup usage varies by country, too. In Greece, it is poured on pasta, eggs, and cuts of meat. Koreans put ketchup on pizza.

-

Availability—Product must be sold in channels that are relevant to the local population. In Indonesia, two-thirds of people buy food in tiny grocery stores or open-air markets, so Heinz must be there.

-

Affordability—Product can’t be priced out of the target market’s range. To meet consumer budget constraints in emerging markets, Heinz employs different packaging sizes or recipes. In Indonesia, it sells billions of small packets of soy sauce for 3 cents apiece.

Firms are organizing themselves differently to address the opportunities presented by developing markets. With over half its sales coming from developing markets, Unilever reorganized into eight regional clusters, six of which were wholly or mainly made up of developing markets. When Kraft Foods broke into two companies, one focused primarily on the United States and slower-growing food categories, the other on developing markets and its faster-growing global snack business.47

Procter & Gamble’s CEO has talked about shifting the company’s “center of gravity” toward Asia and Africa, where it is experiencing growth by targeting the “$2 a day” consumer based on average income. It is attempting to persuade half the men in India who use barbers to embrace at-home grooming, for instance. The “Women Against Lazy Stubble” campaign stresses the benefit

Procter & Gamble emphasizes developing markets in its marketing, for example using well-known Bollywood actors in India to promote its Gillette razors.

Source: STR/EPA/Newscom

of being clean-shaven. In Africa, the company is focusing on communicating to women the benefits of Western feminine hygiene products. In-depth consumer research is generating important insights into these markets, such as that low-income consumers do not always want the simplest products and are every bit as aspirational in their own way as more well-to-do consumers.48

Different income segments exist in developing markets. Although many marketers have successfully tapped into the high end of the income spectrum with luxury goods or by focusing on the growing middle class, opportunities also abound at the broader base of the income pyramid. One useful distinction has been made between: (1) low income ($3–5 a day; 1.4 billion people), (2) subsistence ($1–3 a day; 1.6 billion people); and (3) extreme poverty (below $1 a day; 1 billion people).49

Building Global Customer-Based Brand Equity

In designing and implementing a global brand marketing program, marketers want to realize the advantages while suffering as few of the disadvantages as possible.50 This section explores in more detail how to tactically build strong global brands, relying on the “Ten Commandments of Global Branding” (see Figure 14-4).

1. Understand Similarities and Differences in the Global Branding Landscape

The first—and most fundamental—guideline is to recognize that international markets can vary in terms of brand development, consumer behavior, marketing infrastructure, competitive activity, legal restrictions, and so on. Virtually every top global brand and company adjusts its marketing program in some way across some markets but holds the parameters fixed in other markets.

The best examples of global brands often retain a thematic consistency and alter specific elements of the marketing mix in accordance with consumer behavior and the competitive situation in each country. Snuggle fabric softener offers an example of effectively custom-tailoring the marketing mix.

Understand similarities and differences in the global branding landscape.

Don’t take shortcuts in brand building.

Establish marketing infrastructure.

Embrace integrated marketing communications.

Cultivate brand partnerships.

Balance standardization and customization.

Balance global and local control.

Establish operable guidelines.

Implement a global brand equity measurement system.

Leverage brand elements.

Figure 14-4 Ten Commandments of Global Branding

Snuggle

Unilever launched the fabric-softener product in Germany in 1970 as an economy brand in a category dominated by Procter & Gamble. To counteract negative quality inferences associated with low price, Unilever emphasized softness as the product’s key point-of-difference, naming it Kuschelweich, which means “enfolded in softness,” and displaying a teddy bear on the package. When the product was launched in France, Unilever kept the brand positioning of economy and softness but changed the name to Cajoline, meaning softness, and gave the teddy bear center stage in advertising. Success in France led to global expansion, and in each case the brand name was changed to connote softness in the local language while the advertising featuring the teddy bear remained virtually identical across global markets. By the 1990s, Unilever was marketing the fabric softener around the globe with over a dozen brand names, including Coccolino in Italy and Mimosin in Spain, all with the same product positioning and advertising support. More important, the fabric softener was generally the number-one or number-two brand in each market. Although Snuggle is still a strong market leader, Unilever sold the brand to Sun Products in 2008 to streamline its product portfolio.51

The success of Snuggle reflects the importance of understanding similarities and differences in the branding landscape. Although marketers typically strive to keep the same brand name across markets, in this case, the need for a common name was reduced since people generally don’t buy fabric softener away from home. On the other hand, a common consumer desire for softness that transcended country boundaries was effectively communicated by a teddy bear as the main character in a global ad campaign.

2. Don’t Take Shortcuts in Brand Building

In terms of building global customer-based brand equity, many of the basic tactics we discussed in Part II of the text still apply. In particular, we must create brand awareness and a positive brand image in each country in which the brand is sold. The means may differ from country to country, or the actual sources of brand equity themselves may vary. Nevertheless, it is critically important to have sufficient levels of brand awareness and strong, favorable, and unique brand associations to provide sources of brand equity in each country. VW has struggled to gain a strong foothold in the U.S. market because, unlike its Asian import competitors, it has been less willing to modify its designs for U.S. buyers. Although it has ambitious goals for global auto supremacy, one industry analyst noted, “They need to spend much more time understanding the U.S. consumer.”52

Building a brand in new markets must be done from the bottom up. Strategically, that means concentrating on building awareness first, before the brand image. Tactically, or operationally, it means determining how to best create sources of brand equity in new markets. Distribution, communication, and pricing strategies may not be appropriate in any two markets even if the same overall brand image is desired in both. If the brand is at an earlier stage of development, rather than alter it or the advertising to conform to local tastes, marketers will try to influence local behavior to fit the established uses of the brand. Consumer education then accompanies brand development efforts.

Kellogg

When Kellogg first introduced its corn flakes into the Brazilian market in 1962, cereal was eaten as a dry snack—the way U.S. consumers eat potato chips—because many Brazilians did not eat breakfast at all. As a result, the ads there centered on the family and breakfast table—much more so than in the United States. As in other Latin American countries where big breakfasts have not been part of the meal tradition, Kellogg’s task was to inform consumers of the “proper” way to eat cereal with cold milk in the morning. Similarly, Kellogg had to educate French consumers that corn flakes were meant to be eaten with cold instead of warm milk. Initial advertising showed milk being poured from transparent glass pitchers used for cold milk, rather than opaque porcelain jugs used for warm milk. A challenge to Kellogg in increasing the relatively low per capita consumption of ready-to-eat breakfast cereals in Asia was the low consumption of milk products and the positive distaste with which drinking milk was held in many Asian countries. Because cereal consumption and habits vary widely across countries, Kellogg learned to build the brand from the bottom up in each market.53

Kellogg’s had to educate consumers about cereals in many international markets where breakfast habits were very different.

Source: dbimages/Alamy

This guideline suggests the need for patience, and the possibility of backtracking on brand development, to engage in a set of marketing programs and activities that the brand has long since moved beyond in its original markets. Marketers sometimes fail to realize that in their own country, they are building on a foundation of perhaps decades of carefully compiled associations in customers’ minds. Although the period needed to build the brand in new markets may be compressed, it will still take some time.

The temptation—and often the mistake—is to export the current marketing program because it seems to work. Although that may be the case, the fact that a marketing program can meet with acceptance or even some success doesn’t mean it is the best way to build strong, sustainable global brand equity. An important key to success is to understand each consumer, recognize what he or she knows or could value about the brand, and tailor marketing programs to his or her desires.

Observing that many large companies simply diluted formulas to make less expensive products, Hindustan Lever, an Indian subsidiary of Unilever, made a substantial commitment to R&D and innovation to better serve the Indian market. These efforts resulted in completely new products that were both affordable and uniquely suited to India’s rural poor, including a high-quality combination soap and shampoo, and that were backed by successful new sales and marketing tactics specifically developed to reach remote and highly dispersed populations. Hindustan Lever trained 50,000 to go door-to-door in India to educate consumers there and sell soap, toothpaste, and other products.54

3. Establish Marketing Infrastructure

A critical success factor for many global brands is their manufacturing, distribution, and logistical advantages. These brands have created the appropriate marketing infrastructure, from scratch if necessary, and adapted to capitalize on the existing marketing infrastructure in other countries. We noted above that channels especially vary in their stages of development. Chain grocers have a 50 percent share in China, 40 percent in Russia, but only 15 percent in India.55 Concerned about poor refrigeration in European stores, Häagen-Dazs ended up supplying thousands of free freezers to retailers across the continent.56

Companies go to great lengths to ensure consistency in product quality across markets. McDonald’s gets over 90 percent of its raw materials from local suppliers and will even expend resources to create the necessary inputs if they are not locally available. Hence, investing to improve potato farms in Russia is standard practice because French fries are one of McDonald’s core products and a key source of brand equity. More often, however, companies have to adapt production and distribution operations, invest in foreign partners, or both in order to succeed abroad. General Motors’s success in Brazil in the 1990s after years of mediocre performance came about in part because of its concerted efforts to develop a lean manufacturing program and a sound dealership strategy to create the proper marketing infrastructure.57

4. Embrace Integrated Marketing Communications

A number of top global firms have introduced extensive integrated marketing communications programs. Overseas markets don’t have the same advertising opportunities as the expansive, well-developed U.S. media market. As a result, U.S.-based marketers have had to embrace other forms of communication in those markets—such as sponsorship, promotions, public relations, merchandising activity, and so on—to a much greater extent.

To help make the quintessentially Vermont brand Ben & Jerry’s more locally relevant in Britain, the company ran a contest to create the “quintessential British ice cream flavor.” Finalists covered the gamut of the British cultural spectrum and included references to royalty (Cream Victoria and Queen Yum Mum), rock and roll (John Lemon and Ruby Chewsday), literature (Grape Expectations and Agatha Crispie), and Scottish heritage (Nessie’s Nectar and Choc Ness Monster). Other finalists included Minty Python, Cashew Grant, and James Bomb. The winning flavor, Cool Britannia, was a play on the popular British military anthem Rule Britannia and consisted of vanilla ice cream, English strawberries, and chocolate-covered Scottish shortbread.58

Consider how DHL employed a wide range of communication options to strengthen its global brand.

DHL

DHL, part of Deutsche Post DHL, has positioned itself as “The Logistics Company for the World.” The pillars of this brand positioning are unrivaled speed, efficiency, and strong customer service. The “International Specialists” campaign emphasizes the company’s expertise in local delivery, customs clearance, express shipping, and customer care. The U.S. campaign included a mix of digital, elevator video, airport, and print advertising across the nation and ran in prominent daily newspapers and business magazines. The campaign is also running in global media across 42 key markets, translated into 25 local languages on 280 TV stations. The TV ads featured the classic anthem, Ain’t No Mountain High Enough, sung by rising British star Dionne Bromfield. A social media digital component invited users to upload their own version of the song in a YouTube contest. The campaign was not entirely externally focused. An internal brand engagement initiative required all DHL employees to complete a course that would help their customers grow their business. During the campaign launch, DHL was also the Official Logistics Partner for Rugby World Cup 2011.59

5. Cultivate Brand Partnerships

Most global brands have marketing partners of some form in their international markets, ranging from joint venture partners, licensees or franchisees, and distributors, to ad agencies and other marketing support people. One common reason for establishing brand partnerships is to gain access to distribution. For example, Guinness has very strategically used partnerships to develop markets or provide expertise it lacked. Joint venture partners, such as with Moet Hennessey, have provided access to distribution abroad that otherwise would have been hard to achieve within the same time constraints. These partnerships were crucial for Guinness as it expanded operations into the developing markets that provide almost half its profits. Similarly, Lipton increased its sales by 500 percent in the first four years of partnering with PepsiCo to distribute its product. Lipton added the power of its brand to the ready-to-drink iced tea market, while PepsiCo added its contacts in global distribution.

Barwise and Robertson identify three alternative ways to enter a new global market:60

-

By exporting existing brands of the firm into the new market (introducing a “geographic extension”)

-

By acquiring existing brands already sold in the new market but not owned by the firm

-

By creating some form of brand alliance with another firm (joint ventures, partnerships, or licensing agreements)

They also identify three key criteria—speed, control, and investment—by which to judge the different entry strategies.

According to Barwise and Robertson, there are trade-offs among the three criteria such that no strategy dominates. For example, the major problem with geographic extensions is speed. Because most firms don’t have the necessary financial resources and marketing experience to roll out products to a large number of countries simultaneously, global expansion can be a slow, market-by-market process. Brand acquisitions, on the other hand, can be expensive and often more difficult to control than typically assumed. Brand alliances may offer even less control, although they are generally much less costly.

The choice of entry strategy depends in part on how the resources and objectives of the firm match up with each strategy’s costs and benefits. Procter & Gamble would enter new markets in categories in which it excels (diapers, detergents, and sanitary pads), building its infrastructure and then bringing in other categories such as personal care or health care. Heineken’s sequential strategy was slightly different. The company first entered a new market by exporting to build brand awareness and image. If the market response was deemed satisfactory, the company licensed its brands to a local brewer in hopes of expanding volume. If that relationship were successful, Heineken might then take an equity stake or forge a joint venture, piggybacking sales of its high-priced brand with an established local brand.61 As a result, Heineken is the world’s third-largest brewer in volume, selling in more than 170 countries with a product portfolio of over 250 brands. With brewing operations in about 70 countries and export activities all over the world, Heineken is the most international brewery group in the world.62

Companies are sometimes legally required to partner with a local company, as in many Middle Eastern countries, or when entering certain markets, such as insurance and telecoms in India. In other cases, companies elect to establish a joint venture with a corporate partner as a fast and convenient way to enter complex foreign markets. Fuji Xerox, initially formed to give Xerox a foothold in Japan, has been a highly successful joint venture that dominated the Japanese office equipment market for years and has even outperformed Xerox’s U.S. parent company. Joint ventures have been popular in Japan, where convoluted distribution systems, tightly knit supplier relationships, and close business–government cooperation have long encouraged foreign companies to link up with knowledgeable local partners.63

Finally, some mergers or acquisitions result from a desire to command a higher global profile. U.S. baby food maker Gerber agreed to be acquired by Swiss drug maker Sandoz in part because it needed to establish a stronger presence in Europe and Asia, where Sandoz has a solid base. Sandoz later merged with Ciba-Geigy and now is part of the Novartis group of companies.64

As these examples illustrate, different entry strategies have been adopted by different firms, by the same firm in different countries, or even in combination by one firm in the same country. Entry strategies can also evolve over time. Through its licensee Coca-Cola Amatil, Coca-Cola not only sells its global brands such as Coke, Fanta, and Sprite in Australia; it also sells local brands it has acquired such as Lift, Deep Spring, and Mount Franklin. One of Coca-Cola’s objectives with these acquisitions is to slowly migrate demand from some of the local brands to global brands, thus capitalizing on economies of scale. Branding Brief 14-4 describes how global brand powerhouse Nestlé has entered new markets.

6. Balance Standardization and Customization

As we discussed in detail above, one implication of similarities and differences across international markets is that marketers need to blend local and global elements in their marketing programs. The challenge, of course, is to get the right balance—to know which elements to customize or adapt and which to standardize.

Some of the factors often suggested in favor of a more standardized global marketing program include the following:

-

Common customer needs

-

Global customers and channels

-

Favorable trade policies and common regulations

-

Compatible technical standards

-

Transferable marketing skills

What types of products are difficult to sell through standardized global marketing programs? Many experts note that foods and beverages with years of tradition and entrenched customer preferences and tastes can be particularly difficult to sell in a standardized global fashion. Unilever has found that preferences for cleaning products such as detergents and soaps are more common across countries than preferences for food products.

High-end products can also benefit from standardization because high quality or prestige often can be marketed similarly across countries. Italian coffee maker illycafé maintained a “one brand, one blend” strategy across the globe for years, offering only a single blend of espresso made of 100 percent Arabica beans. As Andrea Illy, CEO of his family’s business, stated, “Our marketing strategy focuses on building quality consumer perceptions—no promotions, just differentiating ourselves from the competition by offering top quality, consistency, and an image of excellence.”65

The following are likely candidates for global campaigns that retain a similar marketing strategy worldwide:

-

High-technology products with strong functional images: Examples are televisions, watches, computers, digital cameras, and automobiles. Such products tend to be universally understood and are not typically part of the cultural heritage. Taiwan’s HTC has employed its “quietly brilliant” brand positioning and “YOU” brand campaign to reinforce its reputation as one of the world’s most innovative smartphone providers.66

-

High-image products with strong associations to fashionability, sensuality, wealth, or status: Examples are cosmetics, clothes, jewelry, and liquor. Such products can appeal to the same type of market worldwide.

-

Services and business-to-business products that emphasize corporate images in their global marketing campaigns: Examples are airlines and banks.

-

Retailers that sell to upper-class individuals or that specialize in a salient but unfulfilled need: By offering a wide variety of toys at affordable prices, Toys’R’Us transformed the European toy market, getting Europeans to buy toys for children at any time of the year, not just Christmas, and forcing competitors to level prices across countries.67

-

Brands positioned primarily on the basis of their country of origin: An example is Australia’s Foster’s beer, which ran the “How to Speak Australian” ad campaign for years in the United States.

-

Products that do not need customization or other special products to be able to function properly: ITT Corporation found that stand-alone products such as heart pacemakers could easily be sold the same way worldwide, but that integrated products such as telecommunications equipment have to be tailored to function within local phone systems.68

7. Balance Global and Local Control

Building brand equity in a global context must be a carefully designed and implemented process. A key decision in developing a global marketing program is choosing the most appropriate organizational structure for managing global brands. In general, there are three main approaches to organizing for a global marketing effort:

-

Centralization at home office or headquarters

-

Decentralization of decision making to local foreign markets

-