PRESENTER MEET AUDIENCE 2

This chapter will focus on the “stars” of the story, the audience.

It’s a nightmare scenario for any designer …

Having worked through the night, you excitedly step to the front of the room. Fueled by caffeine and adrenaline, you present your project idea to the entire office, knowing that this new way of thinking could finally propel your firm to the next level. However, when you finish speaking, the room is silent. There are a few passive head nods ― but no one says a word. Sensing an opportunity, your colleague then steps forward. Having thought about the problem for all of ten minutes, he outlines a mediocre idea, but the atmosphere of the entire room changes. Your coworkers begin to lean forward, nodding their heads in agreement. After his presentation, many questions arise and supporters emerge.

In this disheartening situation, your colleague managed to capture the imagination of the audience.

INTRODUCTION

The strongest communicators acknowledge that while they may be creative and charismatic, the real “stars” are the audience. They recognize that their job is to design an experience that will inform, persuade, and entertain these individuals. After all, the audience members are the ones who will approve the design, assign the grade, or fund the project. The problem lies in determining the best ways to get them to do these things. So, as with any design problem, we ask questions. But if we fail to ask the right ones, we risk sharing the wrong solutions. This chapter will help prompt some important questions that any design storyteller should consider, such as the goals of the presentation, the needs and desires of the audience, and the best way to connect the two.

OVERVIEW OF THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So much has been said of the design process; it’s messy, fuzzy, creative, iterative – there are about as many ways to describe the design process as there are ways to go about it. Design is also a mix of intuitive and deliberate actions,1 such that designers may sense things in their gut, but also rely on information to make decisions. And while we may start over, go backward, and make mistakes along the way, the design process generally follows the same trajectory.

When framing the problem, we cast a wide net around it, exploring its challenges and possibilities. During idea generation, multiple ideas are conceptualized, but none are eliminated. These ideas are then evaluated during testing and refining, where potential solutions are improved upon and perfected. After several iterations, the design solution is ready to be shared. But the process isn’t quite over since much can be learned and applied to future works. The best designers value reflection, which gives them the chance to acknowledge the successes and failures of both their product and process.

This process unfolds for both the design and the story about it.

PARALLELS BETWEEN THE DESIGN PROCESS & STORY DESIGN

| Design Solutions | Presentations | |||

| FRAMING THE PROBLEM why, who, what, how |

Goal | Resolve the right problem. | Tell the right story. | |

| Ask | What are you trying to do? | What are your goals? Who can help you achieve them? | ||

| Tactics | Interviews, observations, site visits, case studies | Determining the audience and how your goals align with their interest | ||

| IDEA GENERATION & DESIGN what, how |

Goal | Generate many ideas and select the best. | Generate many ways and select the best. | |

| Ask | How might the problem be solved? | How might the message be shared? | ||

| Tactics | Brainstorming, sketching | Brainstorming, sketching | ||

| ESTING & REFINING what, how |

Goal | Ensure the best solution. | Ensure the best story. | |

| Ask | Is this the best way? | Is this the best way? | ||

| Tactics | Prototyping, focus group, etc. | Practicing, refining, etc. | ||

| SOLUTION what, how |

Goal | The best solution is put to market. | The best story is told. | |

| REFLECTING what, how |

Goal | Review process & outcomes. | Review process & outcomes. | |

| Ask | Was that the best way? | Was that the best way? | ||

| Tactics | Post-occupancy evaluations, team reflections, consumer feedback | Reading reviews, reflecting, talking with the audience |

GETTING STARTED

It has been said that if “problems are hard to see,” then their solutions are “nearly invisible.”2

Design storytellers help their audiences see the problem for themselves. To do so, they start thinking about how to “package” their ideas nearly as soon as they begin developing them.

There are two important questions that need to be answered early on in this process. The first question centers on the goals for sharing – essentially, why are you presenting your ideas? The second question hinges on who will receive them, namely, who are you presenting these ideas to? Only after those questions are answered can designers begin to think about what to share and how.

This chapter will use the early steps of the design process as a guide to answer the why, who, what, and how questions that design storytellers must answer. Chapter 3 will then move into the process of generating story ideas.

WHY ARE YOU PRESENTING?

It may seem natural to ground your presentation in the merits of your design – certainly, there are many. Though, until the audience knows how badly they need the design, they won’t truly appreciate it. Design storytellers speak to the needs of the audience on the terms of that audience, essentially framing their design as the resolution to the audience’s needs. This takes some reflection on the part of the designer.

So, why are you presenting?

Perhaps you are committed to helping others and believe that you have the best ideas to solve their problems. Or maybe you care deeply about a client and are compelled to improve their circumstances by sharing a timely message. In such cases, consider what your presentation will do for others. Will your presentation help your client obtain the necessary funds to make their project a reality? Maybe your presentation will prompt the audience to make the right decision.

Not feeling quite so righteous? It’s okay if your motivation stems from goals that outwardly benefit yourself more than others. Who doesn’t want to get a good grade or land the promotion? Yet, if you spend a bit of time asking yourself about the root of these objectives, you may find that these too emerge from a noble purpose. For instance, if you get a good grade, you might qualify for the internship at the firm specializing in healthcare design. Or, if you land the promotion, you might be able to share your ideas more broadly, thus benefiting more people. Keep in mind that your list of goals should be short; a long list suggests you’re trying to accomplish too much in the presentation.

With your goals in mind, ask yourself how you need the audience to change in order to make these goals a reality ― this determines the moral of your story. Not only does the moral inspire the audience to take the action you are seeking, it’s central to helping you determine what they will need to know to prompt this action ― this is the content of your design story.

WHO ARE YOU PRESENTING TO?

Whatever your goals might be, chances are you need the audience to connect with your message and, by extension, with you. Thus, you will need to be an attentive design storyteller.

THE ATTENTIVE STORYTELLER

An attentive design storyteller is one that attends to their audience. They create a conversation centered on their audience’s needs and desires. To do this, they seek to understand who they are speaking to, and what makes these people tick. An attentive design storyteller also anticipates their audience’s fears and aspirations, reacting accordingly. For instance, knowing that some board members may be hesitant to change their company’s image, an attentive design storyteller may opt to acknowledge their worries before they share any new ideas.

Creating a memorable experience is critical, one where the audience is the star. Not only are they the star, but, during the presentation, audience members should feel as though they are the masterminds behind the design. This can be a difficult proposition for designers, relinquishing ownership of an idea; after all, our ideas represent our time, creative energy, and livelihoods. Do remember though, that it’s the client who takes on most of the risk. In the end, it’s their money, reputation, and future on the line. They’ll live with the design outcomes long after you’ve moved on to other projects.

Consider the following design presentation scenarios.

If you were a client, which would you prefer?

Audience-focused

Concentrates little on the designer, instead, emphasizing audience concerns.

Words like “your” are used to refer to the design.

Shared Understanding

Highlights mutual interests before guiding the audience toward a new belief.

Words like “our” are used to refer to the design.

Presenter-focused

Designers center on themselves or “their” design.

Words denoting ownership like “I” or “my” are used.

EXERCISE 2.0 WHICH IS THE BEST GAME PLAN?

Use the scenarios above to consider the following interview ideas.

For each, list the strategy represented, and 2–3 risks & rewards.

| Game plan | Reciting your many accolades and cumulative project experience. |

| Game plan | Recounting an experience that you both have had, and using that story to emphasize the opportunity at hand. |

| Game plan | Acknowledge your preparation, but offer to customize the interview according to their goals, since these goals may have changed based on their interviews with other candidates. |

BRIDGE BUILDING WITH UNIVERSAL TRUTHS

Think back to your favorite book or film. Whether is was funny, romantic, or thrilling,it likely struck a chord on an emotional level. Perhaps the circumstances resonated withyou, or maybe you identified with the characters. While the author or director didn’tknow you personally, they managed to connect with you by tapping into universal truths.

What are universal truths?

Universal truths are ideas, notions, and concepts that hold true for almost anyone, regardless of their background. Universal truths are valid across time and place, for instance, love for a family member. Chances are that no matter how old you are, where you live, or how much you earn, you love a family member. Therefore you can likely identify with a message that speaks to this universal truth.

Some common universal truths include:

| We were all children. Our upbringing impacts our decisions(even as adults). |

We desire happiness, though it’s fleeting. While we pursue happiness, it is oftenshort-lived. |

| Stress is inescapable. While the sources of our anxieties mightdiffer, chances are we all face stress andits consequences. |

We are impacted by those around us. Our societal norms influence how webehave. |

| We wanted to be loved and accepted. Love validates us, and acceptance allowsus to feel as though we are part ofsomething larger. |

Change and uncertainty are certain. We will all experience change in our lives,the outcomes of which are often unknown. |

An example of speaking to universal truths can be found in a recent Argentinian advertising campaign which was aimed at increasing organ donor roles.3 Instead of a more traditional campaign targeting altruism, the video’s producers started the spot with a man and his dog. Viewers witness their mutual devotion and see the two sharing in daily activities. Then the man becomes very ill and goes to the hospital. The dog sadly waits at the hospital - night and day, even in the rain. After several days, a female patient emerges from the hospital, and the dog immediately senses a kinship to this stranger. While no words are spoken, to viewers, it becomes evident that she now owns the man’s heart. In essence, the man lives on, and the dog’s purpose continues. If you’re a dog lover, chances are you connect to the message.

UNIVERSAL TRUTH EXAMPLES

Another example in the United States is a recent Truth campaign aimed at tobacco prevention. Having utilized a range of tactics, their most recent spots humorously feature cat videos, which are ubiquitous to the Internet.4

Universal Truth #1- We have seen these videos (or created them).

Universal Truth #2- Cats are funny, weird, cute, etc.

Near the video’s end, a message notes how many cats die of cancer due to their owner’s smoking. In essence, if you love your cat, you won’t smoke.

Universal Truth #3- If you won’t save yourself … at least save your cat.

In design, we can speak to universal truths in many ways.

For instance, if you are developing designs for an Alzheimer’s care unit, you may connect to the audience by speaking to their love of family.

Universal Truth- They cared for us; now we should care for them.

Figure 2.0

“Man’s best friend” can be a subject of a universal truth

IDENTIFYING THE AUDIENCE

Given that the audience is so important, it’s essential to identify their characteristics and motivations. In her book Resonate, Nancy Duarte5 outlines a process of audience segmentation, in which a presenter analyzes audience characteristics, including demographics, psychographics (i.e., personality), and firmographics (or business setting).

However, no two audiences will be the same. Even within a seemingly homogeneous audience, individuals may have varied backgrounds and even conflicting beliefs. While it is impossible to know everything about everyone, it is helpful to gain as much insight as possible about an audience relative to who they are and what they want.

WHO IS AT YOUR TABLE?

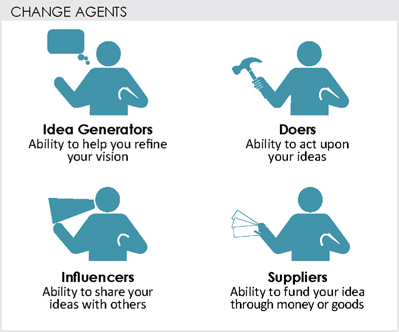

When you’re thinking about your audience, imagine them as your guests at a dinner party. Did you invite them to your table because they will help you get ready (doers), or bring the expensive wine (suppliers)? Perhaps they’ll bring a distinguished guest (influencers), or maybe they tell the best jokes (idea generators). Consider these individuals as the agents of action in your audience, since they have the ability to move your idea forward, provide funding, hone your ideas, or share those ideas with others. These change agents are the real stars of your story.

There may be times when an intended audience (i.e., Board of Directors, Parent –Teacher Association, etc.) is more effectively reached through others. For instance, if your goal is to help your client generate funds for a new classroom wing, parents may be apathetic to your appeals. However, if you enlist their children (as influencers) to share your message, the parents may be more responsive to your request. You can excite the youngsters by sharing design ideas, so that they, in turn, go home and discuss the possibilities with their parents. Of course, you want to leverage such a tactic ethically, but these types of clever targeting strategies can be very useful.

Figure 2.1

Consider who in your audience can help you achieve your goals

AUDIENCE CHARACTERISTICS

DEMOGRAPHICS

| Age | Education | Ethnicity | Gender | Location |

PSYCHOGRAPHICS

| Personality Are they Introverted/Extraverted? How do they feel about change? Are they disciplined? |

Values What do they respect? What are their priorities? |

Attitudes What is their outlook on life? How do they react to events? |

||

| Interest How do they spend their time and money? |

Knowledge What do they already know? Where do they get information? |

Lifestyle What is interesting about them? |

CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION

| Personal-domain | Public-domain | |

| How large is their family unit? | How large is their business? | |

| What does their family do in the space? | What do they do? | |

| What is in proximity of the residence? | What types of people do they employ? |

MOTIVATIONS

| Personal-domain | Public-domain | |

| Examples: | Examples: | |

| Better support for daily activities | Increased profitability | |

| Enhanced family connectivity | Employee recruitment & retention Company values |

WHAT EXPERIENCE WILL THEY HAVE?

Use your knowledge of the audience to speak to their needs, but keep in mind that they may not believe in the need, or believe that your design is the solution. This obviously makes your job more difficult since you will need to change their positions. At first, this can be disheartening since they don’t appreciate your ideas as much as you had anticipated. But it’s human nature for people to “value their own conclusions more highly than yours.”6 So plan their experience from their perspective. Essentially, what is the best way to start from their position, but change their hearts, minds, and beliefs?

EXERCISE 2.1 AUDIENCE CHARACTERISTICS

Think about the audience from your last presentation and use the chart above to reflect on their characteristics.

How much did you know about the audience?

How did that knowledge influence your presentation?

How else might this knowledge influence your presentation?

WHAT ARE YOUR GOALS FOR THE AUDIENCE?

Prior to hearing your message, your audience will likely do, think, or believe something – and may be very satisfied with that ‘something.’ Nevertheless, your goal is to prompt them to do, think, or believe something else (i.e., contribute, act upon, or believe in your ideas).

TYPES OF AUDIENCE CHANGE

| dislike | to | like |

| naive | to | wise |

| maintain | to | change |

| doubt | to | believe |

Hence, you want them to change as a result of the experience you’re creating. For instance, a company’s CEO may want to keep her private office, but your goal may be to help her see the benefits of an open office solution – thus changing her beliefs.

REWARDING THEIR CHANGE

For any number of reasons, some in your audience may not appreciate your ideas. They may feel that a new design is unnecessary, fear change, or worry that the design itself may not meet their needs. Whether their concerns are valid or unwarranted, these issues are important to them, and should not be dismissed. Your design may provide countless benefits, but remember that change is hard – and sometimes scary – so highlighting rewards can help to motivate the change.

For instance, when a company is relocating, the ensuing changes can be both exciting and distressing for staff, and there will likely be some resistance to change. Employees might have to settle for smaller workstations, and if they don’t understand the benefits of this change, they will resent the design – and perhaps you by extension.

To alleviate concerns, consider how to convey the rewards of the change – both big and small. The employees might accept smaller workstations if they are rewarded with views of the outside or access to a coveted fitness center. More broadly, the new location might accommodate more employees, thus reducing their personal workloads. Ensure that you know what the client’s objectives are so that you can weave them into your design story.

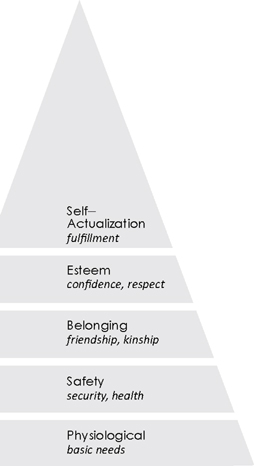

These rewards happen at an individual level too. For instance, a consumer may be willing to spend more on a product, if they can trust that it’s reliable, or feel that it was ethically produced. Such rewards can range from basic necessities to lifelong goals; consider the rewards against Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.7

Does moving to a smaller office satisfy a basic need? Probably not, but the promise of a newfound sense of openness may motivate the audience to make the change you are requesting.

WHOSE CHANGE IS IT?

It’s human nature to desire personal gain, and audience members certainly like to hear about rewards that directly impact their lives, yet they may care nearly as much about the impact on others. So, while your design may not directly change their own experience (i.e., micro benefits), the design may improve the status of their company, community, or even mankind. For example, paying extra for recycling bins may not benefit one employee in particular, but doing so will enhance the firm’s sustainable practices (group) and preserve the environment (macro benefit). Or a water feature designed for an emergency room waiting area may go unseen by the physicians listening to your presentation, but if their patients are calmed by its presence, it may help them to better diagnosis their patients’ ailments. The key is to thread these rewards back to the lives of the target audience.

Figure 2.2

Maslow’s original Hierarchy of Needs

HOW ARE YOU PRESENTING?

We come to change our beliefs based on the different ways we approach a message. Some of us may be more likely to change our minds based upon rational evidence, whereas others trust our “gut” instincts. Your goal is to align your message with the audience’s desires through your delivery, which brings us to answering questions surrounding how we might persuade the audience.

To explain the different ways an audience might approach information, scientist and filmmaker Randy Olson cited four areas of the body, each having different motivations (e.g., groin, gut, heart, and head). He suggested that speaking to our desires appeals to our groin, a nod to our intuition charms our gut, tugging at our emotions speaks to our heart, and finally, rational evidence sways our head. Olson stressed that given our biological predispositions to reproduce, appeals aimed “below the belt” affect everyone, but fewer individuals are likely to be convinced through their heads. He suggested that speakers first target the lower three areas to initially gain interest, before actually speaking to their heads.8

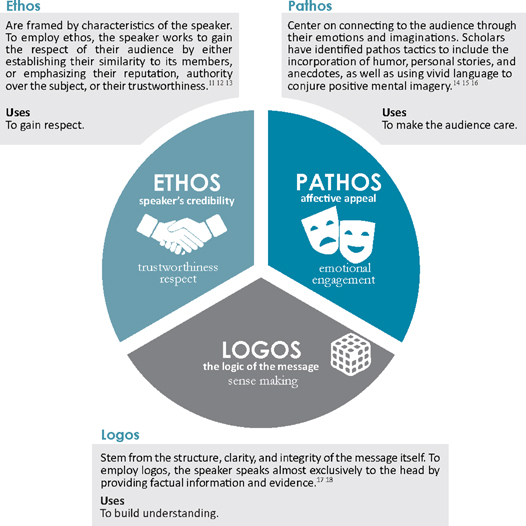

PERSUASIVE APPEALS

Olson is not the first to recognize multiple pathways to persuasion. Greek scholar Aristotle suggested that the roles of the speaker, their message, and their audience are inherently connected, and outlined three means to persuade an audience. These include the speaker’s character or credibility (ethos), the logic of the message at hand (logos), and the emotional arousal of the audience (pathos).9 10

Figure 2.3

Aristotle’s persuasive appeals

WHICH APPEAL IS BEST?

While most design presentations will use all three tactics, they may vary in terms of which is emphasized. To determine which appeal is best, consider your personality (and your level of comfort), the meaning and tone of your content, and, of course, the personalities of those in your audience.

Figure 2.4

There is an inherent relationship between a speaker, their message, & their audience

There is also some evidence to help speakers identify which appeal might work best for their specific situations. TED Talks are a popular venue to convey ideas and their popularity helps illuminate the relationship between a speaker, their message, and their audience. In studies of TED Talks, whose online videos focus on Technology, Education, and Design, communications researcher Scotto di Carlo found that Talks were often introduced using story, or by providing context about a given topic. In fact, 43% percent of the talks in her study had incipits (or entry words) that recounted a personal story or experience; this suggests that pathos, or appeals to the heart, played an important role early in a Talk.19

To understand why some messages are more apt to be shared, communications professor Jonah Berger conducted a study examining how people opted to forward nearly 7,000 online articles. His team initially found that topics considered interesting and useful were more likely to be shared. Going further, they found that articles conveying sadness were 16% less likely to be shared, while those inspiring awe were 30% more likely to be shared. To the research team, it seemed that positive articles were more likely to be shared; however, articles that made people angry or anxious were shared at similar rates.20

So, what was the difference?

Articles that evoked a physiological response (i.e., heart racing, palms sweating) – whether positive or negative – were more likely to be shared. Brain scans suggest these types of articles stimulate our mirror neurons.21 Essentially, when the emotions are deeply felt, we are more likely to care; thus, we are more likely to share.

This prompts the question, should designers aim to get their audience worked up about a problem, or simply delighted in the solution? Communications consultant Nicholas Morgan suggests that we do both.22 In other words, a good design story uses the tools of the trade (written, verbal, and visual messages) to give the audience a sense of urgency about a problem. Only once they are convinced that the problem is dire, do we offer the solution.

WHAT IS YOUR MESSAGE?

Knowing the audience, and knowing how to approach them are just the beginning of our questions. Design storytellers should also explore how their content aligns with their audience.

Is your content inherently analytical or emotional? Evidence suggests that there is great potential in appealing to the emotions of the audience, especially if affective appeals will sway audience members. But, what if emotion doesn’t inherently drive your content? The key is to wrap it in a story that does. For instance, statistics represent people. Each number accounts for a life that matters to someone else. Get the audience to care about that person’s plight, then highlight how your design will improve their life – this will help the audience to better remember the merits of your design.

LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT TOOLS

The language we use to tell the story – both visual and written – will be critical. This language should be in terms familiar to the audience. So do your homework. As you ask questions about the audience, answer these questions with words and images that represent their current characteristics and terms (i.e., slogans, adjectives, mission statements, brand imagery, pictures in the home, stylebooks, etc.). Also, compile aspirational images that best represent the tone you’d like to depict and the benefits of the design – the more of each the better. Use these to determine any underlining trends. Are there vast differences between their current language and your intended tone? What do these differences tell you about how they may react to your message? This collection of representations should serve as a reference. Use it to meet the audience where they are, and guide them toward the better destination. This is the cornerstone of your creative brief.

CREATIVE BRIEF

A creative brief can serve as an important guide during your story planning process. Start by examining the words, images, and representations that you have collected. What trends and themes do they represent? Use your assessment to write a statement that highlights your intentions. This statement should be short and direct, but with enough elaboration to provide a shared vision and collective purpose.

Steps for developing a creative brief:

1. Pose questions.

2. Conduct research to inform your answers.

3. Determine themes.

4. Define a key message.

STORYTELLING IN PRACTICE

How do you make your audience feel smart?

Over many years of designing motion media and visual effects for television and feature films, it has consistently been my experience that if you make your audience feel smart they will love you for it – and they may not even realize why. I believe this notion holds up in any medium and any venue.

Once I was tasked with creating a series of “HUD” or Head’s Up Display graphics for a sci-fi film. The director wanted to convey that the protagonist was receiving a massive download of information – and this in a shot lasting only a few seconds. There is always the temptation to dumb down a moment like this in the expedience of exposition to move the scene along. Instead of spoon-feeding the audience by stating the obvious, we wove the essential text elements necessary to convey the story in with diagrams and schematics of real objects and technology that had perhaps no immediate pertinence to the story – but which conveyed a visual richness and a certain ring of truth about them. Implicit in the design was the idea that the audience was sophisticated enough to surmise authenticity from information present on-screen for only a fraction of a second. The attention to what might seem like throwaway details in visual storytelling lent a certain gravitas to the moment in the film that might otherwise have seemed simplistic. The sequence was well-received because the audience got to connect the dots and derive significance in their own minds from the whole.

SUMMARY

The success of a presentation often hinges on its design. Knowing this, the best design storytellers go far beyond decisions about color and font. Instead, their presentations represent a comprehensive decision-making process. In fact, there are many similarities between designing products and spaces and designing a presentation. In both, asking the right questions is key. These questions should be aimed at defining your goals, understanding who will be receiving your message through their characteristics, backgrounds, and beliefs, and what you want them to do about your message. In other words, how will they change as a result of your presentation?

To prompt this change, consider incorporating several storytelling tactics into your presentation:

Aim to be attentive and to connect to your audience through universal truths, or concepts that hold true to almost everyone, everywhere.

Consider how you might emphasize any potential rewards for making the change.

Determine which type of appeal (ethos, pathos, or logos) might prompt this change.

Once these factors are established, consider the inherent tone of your content and how it might be shared with story.

FOR CONSIDERATION

To hone your storytelling skills, consider the following:

Reflect on your favorite teacher or mentor.

• When delivering a message, what did they do differently?

Reflect on your own work.

• Refer to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Consider how your projects fulfill the needs of others.

• What kinds of changes does your work typically require?

• What are potential rewards for these changes?

Become a keen observer of messaging and advertisements.

• What universal truths are used?

• Are the messages intended to sway the groin, gut, heart, or head?

• Which appeals are used (ethos, pathos, or logos)?

• Identify effective and ineffective strategies.

TERMS

| audience segmentation | firmographics |

| demographics | psychographics |

APPLICATION 2.0

To design a powerful presentation, first some important decisions must be made about the audience. Think about an upcoming presentation and consider the following:

1 Use the Audience Characteristics table on page 25 to analyze your audience. Remember to focus on the most influential audience member (the person who has the power to advance your project).

2 Identify how you want this person to change as a result of your presentation. For example, do you want them to move from dislike to like, doubt to believe, etc.?

3 Use your audience analysis answers to identify which universal truth might best evoke the desired change in this audience member.

4 Also, use your audience analysis to identify the most effective appeal (ethos, pathos, or logos).

5 In the area below, craft a one-paragraph creative brief that responds to these goals; aim to use the language of your audience (see page 29).