STORY DESIGN 3

This chapter will focus on conceptualizing, designing, and testing stories.

The launch of John’s crowdfunding site was now only a few days away, and while he was confident that his idea was solid, he knew that potential funders had to understand who it would actually help. But after prototyping and rehashing ideas with his team for weeks, he was completely drained. Feeling exhausted, he went home for the evening. Waiting at the door was his bulldog, Lilly. She had likely been waiting there for him all day. “Now that’s dedication,” John thought to himself. Just maybe that was an idea he could work with, “dedicated to those …” John went for his pen.

While it’s doubtful that John will have a sudden epiphany, his idea might lead to another and then another — culminating in his pitch.

INTRODUCTION

There are two kinds of stories within design presentations. The previous chapters explored the role of “S”tories (with a capital S) which are used to represent the values that prompt audience change. These Stories are complete with characters and conflict and are often folded into your presentation. Yet, virtually all design presentations can be thought of as stories – with a little “s.”

We laid the groundwork for both “S”tories and stories in Chapter 2, by identifying your goals, your audience, and determining some initial messaging strategies. This chapter will explore the ideation, design, and testing of your message, by first refining questions surrounding what you’ll be saying and how. These answers will help shape the contours of your overall design story, whether it is aimed at sharing your point of view, your project, or your fit for a position or project team.

RETURNING TO THE CREATIVE PROCESS

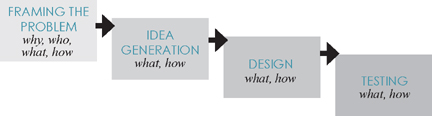

Recall that our process will be similar to the design process (see page 20). In this chapter, your goals will be used to help determine the focus of your message. The aim of the idea generation stage is to be bountiful yet economical … bountiful, in that the process should result in many ideas to choose from and economical in that each idea represents a minimal investment of your time. The story is shaped during design, where you’ll finalize, structure, and refine your message, then test its strength and appeal before determining how to share it.

Figure 3.0

Steps in presentation design

DESIGN PRESENTATION AREAS OF FOCUS

This chapter outlines idea generation for three types of these stories (with a little “s”), each of which can be very important in any design career. The first is focused on you as a designer, essentially, your point of view. The second type involves an outcome of your work such as a project summary. The third focuses on a position or project you hope to win, in other words, a pitch.

| Point of View | Project Summary | Project or Position Pitch | ||

| DESIGN PRESENTATION AREAS OF FOCUS | GOALS | Convey your design approach & background | Highlight a project | Display your fit for an opportunity |

| AUDIENCE | Potential clients or employers | Potential clients, employers, or instructors | Those who are screening candidates | |

| AUDIENCE CHANGE | Uncaring to caring | Unaware to aware | Doubt to believe | |

| PROTAGONIST | You | The project | The opportunity | |

| FACTORS | Your unique background Your motivations |

Project challenges, opportunities, & triumphs | Your unique qualities Your interest in the opportunity |

POINT OF VIEW

Discovering the source of your point of view (POV) means exploring the causes and corresponding effects of your life’s events. Doing so can help you discover what drives you and your decisions as a designer. To start generating ideas for your POV, answer as many of the questions as you can from the list below. Some of these questions will likely be easy to answer while others will be more difficult. Try to answer at least 10 of the questions (or question groupings) with at least two from each category (e.g., Yourself, Your Motivations, etc.). Once you have an answer to a question, don’t stop there; continue to ask yourself, why? Doing so will help you unearth a common theme.

YOURSELF

• Why are you reading this book?

To the answer from above, ask yourself why?

• List 4 characters or historical figures you identify with.

How are these individuals similar?

• How would you define your life?

How do your actions support that definition?

• Describe yourself in one word.

What word would others use to describe you? Are these words similar or different?

• Who are your earliest influences?

How did they shape your life?

• List 4 events you will remember forever.

How have those events shaped you?

• What are you optimistic about?

Why do you feel this way?

• What brings you joy?

What keeps you up at night? Are these things related?

YOUR MOTIVATIONS

• What inspires you?

How do you use this inspiration?

• What is the first thing you think about each morning?

What is the last thing you think of at night?

• If you could take a trip with anyone (living or dead), who would you take?

Where would you go?

• What motivates you?

How do you act upon that motivation?

• What gives you pride?

Why do you feel this way?

YOUR CONTRIBUTIONS

• How are you changing the world around you?

How might you change the world in the future?

• What advice would you give to those just starting out?

• Why did you choose to design?

What problems do you hope to alleviate?

• Describe an opportunity you embraced.

What was gained from this?

YOUR PROCESS

• What is your typical day like?

Why is it like this?

• Describe when you creatively solved a problem.

How did you accomplish this?

• Describe when you overcame a challenge.

How did you do so?

• Describe your design process.

Why is it like this?

YOUR EXPERIENCES

• Describe a regret or mistake.

What have you learned from this experience?

• Describe an accomplishment.

How can you take it further?

• What decisions have brought you to this moment?

At the end of your career, what do you hope to have accomplished?

• What advice would you give to your child-self?

• What would you remind your elderly-self?

PROJECT

The protagonist of a project story is often the design itself, in that the project goes through a series of challenges that culminate in the best possible outcome. While such stories convey design merits, they can also provide insights into how you navigate the design process, and even your tenacity and grit. To get started, select a previous project (or one nearing completion) and answer the following questions about it. Aim to answer at least 10 of the questions (two of which should be from each category). Then repeat the process, continuing to delve into the reasons for your answer; this will help you uncover the essence of the project. You might find that the questions all point to a central theme.

PROJECT PARAMETERS

• Who was the project for?

How are they unique?

How did you identify with these individuals or come to understand their needs?

• How would you define the project?

How did your design decisions support this definition?

• If you selected the project parameters (i.e., topic, scope, size, etc.):

Why did you select this topic?

Did anyone influence this selection?

• If you were given the project parameters (i.e., topic, scope, size, etc.):

How have you reframed or evolved these parameters?

• Do you feel passionate about the project topic?

How has your passion grown?

• How did you come to understand the project parameters (research, observation, etc.)?

How did those findings influence your design?

• What goals did you have for the project?

How did your solution respond to those goals?

PROJECT CONTRIBUTIONS

• Who would benefit from knowing about your project and why?

• How could knowledge or ideas from your project inform or guide others in other disciplines/areas?

• How could knowledge or ideas from your project inform or guide future generations?

PROJECT PROCESS

• Describe your design process for the project.

• Describe the project’s challenges and opportunities.

How did you approach these?

• What might you do differently?

USER EXPERIENCE

• How would others respond to your project?

How might they use or experience your solution?

• How would users see this project as unique?

What similiarities would they see?

• How might users view this project’s accomplishments (or failures)?

PITCH

Designers are often tasked with convincing others that they are the best possible candidate for an upcoming opportunity. In such scenarios, a pitch can make the difference as to whether the opportunity goes to you or a competitor. To start planning for this type of story, select an upcoming opportunity you’re hoping to gain (either a design project or a position) and answer at least 10 of the following questions (two of which should be from each category). Once you have an answer to a question, again, don’t stop there, continue to examine your response and your reasons for that response by asking Why. This will help you determine on a deeper level why you are the best fit for this opportunity. It may happen that your answers all center on a common theme.

YOURSELF (in this role)

• Why are you hoping to receive this opportunity?

To the answer from above, ask yourself why?

• What makes you unequivocally qualified?

Why are these qualities important?

• How would you define this opportunity?

How do your actions support that definition?

• List goals for this opportunity.

How would your solutions respond to these goals?

• How would you uniquely go about understanding the parameters of the project or position?

• What would influence your decisions?

How might this shape your work?

• List 4 events you will remember forever.

How would these shape your approach?

• Describe yourself in this role.

How would others describe you? Are these terms similar or different?

YOUR MOTIVATIONS

• What inspires you?

How does that inspiration support this opportunity?

• What motivates you?

How does that motivation intersect with this opportunity?

YOUR CONTRIBUTIONS

• How would you embrace this opportunity?

How would your actions support this?

• Outline your potential contributions.

How might these contributions improve the project?

YOUR PROCESS

• What would your typical day be like during this opportunity?

Why is it like this?

• Describe challenges and opportunities that would accompany this opportunity.

How would you approach these differently from competitors?

YOUR EXPERIENCES

• Describe a regret or mistake.

How would you apply what you learned from that experience to this opportunity?

• Describe an accomplishment.

How does that accomplishment parallel this opportunity?

• Describe your decision-making process.

How is your process uniquely suited to this opportunity?

HONING THE MESSAGE

By answering the previous questions AND asking yourself the reason for your answers (i.e., why?), you may start to recognize patterns. These underlining themes can be very valuable in framing your story. In the case of the Point of View answers, these themes begin to suggest your core values. These values, in turn, shape your decisions. For the Project questions, your answers speak to the rationale behind your design decisions. Finally, answers to the Pitch questions can help highlight how your values coincide with the opportunity at hand, making you the best candidate.

Take these overarching themes and use them to craft the essence of your story. To do so, pair the overarching theme with the change you are seeking from the audience (i.e., what you want them to do, act, think following your presentation; see Chapter 2). What parallels can be drawn? What universal truths might connect the two (Chapter 2)? This is the central message or big idea driving your presentation.

Figure 3.1

The process of honing your message involves merging goals & themes

According to Nancy Duarte,1 a presentation’s “big idea” should convey your unique perspective while communicating what’s at stake. Remember that the audience will likely change in response to your message, so your central idea should direct this change.

Use what you have learned from your answers and subsequent exploration to examine your creative brief, which was started in Chapter 2 (see page 29). Remember that this statement should be clear, direct, and memorable. Keep the creative brief to no longer than one paragraph. In fact, some creative briefs are so succinct that they can fit on a bumper sticker.

SEEKING INSPIRATION

While honing your messages, don’t overlook outside sources of inspiration. Creative individuals are constantly on the lookout for fresh insights. As you design your story, be open to the world around you, seek ideas from a diverse range of sources. Attend lectures and events, explore online resources, read books and magazines, talk with others — absorb it all. When doing so, be hyper-vigilant, taking note of your assessments. Record your ideas using a sketchbook, digital device, or web program. Over time, you’ll develop an inspiration-gathering process that is uniquely yours, and it will be a catalyst for many ideas. Choreographer Twyla Tharp calls her process “scratching,” during which she places her sources of inspiration for a project in a box and saves these collections long after a project is complete. In turn, the boxes serve as a project archive and she can revist them to inform future projects.2

Figure 3.2

Save sources of inspiration

BRAINSTORMING

In addition to seeking outside inspiration, another way to gain ideas is with brainstorming. Advertising executive Alex Osborn offered this concept for idea generation in the 1950s.3 His technique was quickly mainstreamed into our creative consciousness, and today it’s hard to imagine design without it. Chances are you have participated in several brainstorming sessions yourself – some probably more successful than others. To make the most of your brainstorming sessions, consider the following strategies:

BRAINSTORMING TIPS

Consider if your goals are to gain diverse opinions or expert solutions and invite participants accordingly.

Aim for a small group of individuals who are interested in your project (if the group is large, break participants into groups of 4–5).

Write down your central message in the center of your workspace (either on a board or at a table).

Begin the session with a question prompt that relates to your goals.

Only focus on one question for each session. Exploring more questions might cause participants to prioritize ideas.

Appoint a moderator to write down all ideas. Remember that at this stage ideas should be cheap, plentiful, and unjudged.

Aim for bursts of ideas. Keep the sessions short and focused.

Value your unique perspective, and don’t be afraid to share personal accounts (instruct others to do the same).

Value the perspectives of the other participants as well.

Avoid lingering on one idea for too long. When things slow down, stop the session and offer a report to participants.

IDEA DROPS

Sometimes seeing a collection of ideas is more fruitful. Idea drops use visual language to collect ideas, often in the form of sketches and imagery. The goal is to represent ideas quickly and see them all at once.

Idea drops can be done individually or with a small group. If you are working with a small group, you may want to give them homework in advance, such as bringing reference images.

VISUAL BRAIN DUMPING TIPS

Write down the central message where it’s visible to everyone.

Utilize the images from your creative brief notebook, online searches, or those provided by clients. Also, provide ample space with which to draw sketches and make notes.

Set a time limit.

Don’t worry about the order of the sketches — remember, it is not yet time to evaluate ideas.

Avoid lingering on one idea; this can happen later.

DESIGNING THE STORY

Chances are your ideation sessions will have left you a little tired but also brimming with ideas. The design process helps you to prioritize those ideas. Once you have developed a central theme (i.e., your highest priority), you can begin to craft sub-themes to support it, a sequence around it, and a to it.

DEVELOP SUB-THEMES

A central theme gives meaning to your ideas, while sub-themes help you to elaborate on them. Each sub-theme is bound to your central message but adds additional depth and resonance. While developing sub-themes, explore the answers to Point of View, Project, or Pitch questions as well as your content (e.g., project deliverables). Look for patterns and areas of alignment to the central theme.

Consider the following questions:

• How do your sub-themes compare in terms of scale, context, meaning, etc.?

• How do these ideas connect, parallel, or contrast?

• How do these patterns speak to the values you’re aiming to portray while encouraging the audience change you’re seeking?

SEQUENCE

The structure of a message can have a profound impact on how it’s interpreted. Consider this to be the sequence of a presentation. A great sequence can help the audience follow along, build and maintain their interest, and leave them willing to make the proposed change. A poorly orchestrated sequence can leave the audience confused, irritated, apathetic, and unlikely to respond positively to your ideas.

While it can be easy to get lost in the details of a presentation (and lose sight of your goals), good design storytellers view their presentation holistically, almost as if they are taking the audience on a journey – each step supporting the goals at hand. With this in mind, plan the overall structure first. It’s not yet time to focus on the introduction or conclusion. Instead, concentrate on developing an ordering of your ideas that is logical and builds in momentum, thus maintaining the audience’s attention.

Consider the following ways to organize your presentation:

Sequential

| Themes are ordered via a step-by-step sequence (i.e., once one event occurs, it sets in motion a series of corresponding events) For example, “if the customer wants to use this device, they simply start by…” or “I began this process by…” | |

| This structure works particularly well for highlighting what a client wants to have happen and how that scenario can come to fruition, like actions culminating in a reward or a plan moving forward. | |

| Pros: Simple Provides the potential to build momentum Example: Need to fulfillment |

Cons: Can lose audience attention |

Chronological

| Themes are arranged according to their progression in time (either forward or backward), for example, a day in the life of a customer, or a company’s past, present, and future. This order is often the simplest and easiest type of presentation to comprehend. | |

| Pros: Simple Easy to understand |

Cons: Predictable |

Spatial

| This method describes how themes relate to each other either geographically or in a physical space. This is akin to touring a space or city, and it can help the audience see how concepts “fit” with one another, showing relative location. For example, “Upon entering the space, a client would …” or “While walking through Times Square, …” | |

| Pros: Suggests relationships |

Cons: Reliant on the audience’s spatial thinking and their ability to create mental images |

Information Significance

| Themes are ordered by their relative importance ― either from least to most important, or vice versa. The former provides a sense of increasing momentum, whereas the latter is similar to the newspaper editor’s creed of “don’t bury the lead,” in that the headline provokes reader interest. More detailed information and less significant aspects of the story are reported near the end of the article. The editor’s premise is that readers choose how far into the article they wish to read. However, in a presentation, the audience generally does not have the option of abandoning the message, so the danger is in knowing how much to elaborate on the information, but still retain their attention. | |

| Pros: Establishes audience interest Example: Insight with corresponding information |

Cons: May lose audience attention |

SEQUENCES WITH CONTRAST

Organizing a presentation via sequential steps, time, location, or information significance are all fairly linear methods. They are easy to follow since they have a clear starting point and a natural progression. However, if your goals are to compare schemes, highlight gaps, or point out counterintuitive ideas, you may want to contrast ideas in order to provide both explanation and added interest.4

Problem-Solution

| The central theme in this type of presentation is solving a problem. Acknowledging the problem first can help convince the audience that they need to make a change. Once the issue is made known, they are then provided with a solution. For example, “roughly 1 in 16 Americans suffer from some form of arthritis. These individuals can face problems with … and this idea will help to alleviate their struggles.” | |

| Pros: Compares something unfamiliar to something familiar Examples: Impossible to possible; hope to reality |

Cons: Audience might disagree with the problem, thus invalidating the “solution.” |

Compare-Contrast

| This strategy compares two elements or elaborates on multiple perspectives. For instance, how things are now compared to how they could be in the future. Politicians often use this tactic when challenging incumbent candidates. In essence, “if you elect me, your future will be better.” When multiple parties are involved, you can also acknowledge their unique perspectives on the theme at hand. For example, how the politician might improve the lives of children, families, and the elderly, or sharing design features of a hospital according to the perspectives of staff, patients, and visitors. | |

| Pros: Highlights differences & gaps Examples: What is now to what could be; what was to what is now |

Cons: Can confuse audience |

Advantage-Disadvantage

| These presentations often start by discussing the central issue; sub-themes are then shared according to their advantages and disadvantages for the audience. This can be a useful tactic since clients want to maximize potential benefits (and often understand the reasoning behind a design decision). While clients are likely to want to understand potential benefits, they might grow confused about which sub-theme is being discussed. As such, presenters utilizing this structure should provide visual indicators or other devices to help the audience “track” where they are in the presentation (See Chapter 6). | |

| Pros: Provides relatable information Example: Ordinary to superior |

Cons: Audience may want to “cut to the chase” and hear only about the best scenario. |

Cause-Effect

| This structure uses causal reasoning to highlight the positive or negative consequences of a decision via an action and its corresponding reactions. Essentially, if this, then that. For instance, “if you build a new space, your company will likely recruit first-rate talent” or “if you continue down this path then … will happen.” | |

| Pros: Suggestive of consequences | Cons: Audience might not agree with the correlation of events. |

WHICH SEQUENCE IS BEST?

There is no one simple way to determine which sequence will work best for a particular scenario and it may take a few attempts to get it right. However, editing, storyboarding, and, of course, feedback will provide you with tools to help weigh your options.

EDITING YOUR STORY

There is an implied violence in the act of editing. Film editors traditionally had a “cutting room floor,” where discarded shreds of films lay waiting to be swept away. Designers are told to “kill their darlings” to decide if their most beloved idea is actually holding them back. Meanwhile, the combination of the letters “V” and “E” can send even the most stoic of architects into fits, since they mean the prospect of scaling back or “cutting” out design ideas via value engineering.

Yes, editing can be a difficult process, but it is critical. There will come a time when you will simply have too many ideas or too much content. Moreover, if you attempt to speak to everyone, you risk speaking to no one at all. And remember, as an audience-focused presenter, your goal is to tailor your message to the change agents within your audience (see page 24). If they are swimming in information, chances are they may not remember any particular parts of your message. Thus, you must edit on the behalf of your audience. Once you have determined your presentation’s sequence, reexamine it against that central idea and the audience change you are seeking. Any sub-themes that fail to “speak” to that idea should be considered irrelevant and removed.

If editing is painful and doesn’t come naturally to you, remember when you’re receiving feedback about an idea keep yourself from thinking of it as a personal critique. A good critique isn’t aimed at you as a person but is an objective examination of your work and ideas. Keep in mind that editing can actually be a liberating process as it frees you from grasping too tightly to weak ideas. And even if you think you have arrived at your best ideas, try another option. You can always go back to your original idea – or revive your darlings – so don’t be afraid to grab the red pen.

STORY EDITING GOALS

Narrow down your ideas, and aim to be succinct.

Eliminate sub-themes that fail to support the big idea.

Explore how the sub-themes relate to each other.

Explore alternate options — never settle for your first idea without exploring other possibilities.

Share your ideas with others; who can offer a new vantage point on your work.

“S”TORY DEVELOPMENT

Your presentation is a story in and of itself, but to make it tangible and relatable, consider including a singular Story. To do so, explore your presentation sequence and determine where explicit story elements support your central theme.

There are many ways a Story can be threaded into a design presentation. A “S”tory can be used to begin the presentation and be revisited at its conclusion, or a protagonist can provide structure to the presentation as the audience explores your ideas through the character’s eyes. Stories can be factual accounts or fictional tales. The key is to be authentic.

Good storytellers know what facts the audience needs to understand a story, when to stretch out the details, and when to gloss over events.5 Applying this to a design presentation means your Story will need to garner attention almost immediately, but still leave enough time to focus on the design you’re presenting. To do so, include only the necessary details to spark interest and use vivid words when describing the aspects of the design itself.

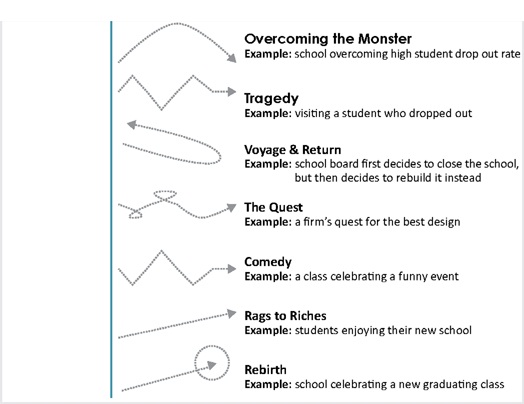

In his 2004 book Seven Basic Plots, journalist Christopher Booker asserted that stories share common themes of: initial anticipation, dream (i.e., unrealistic invincibility), frustration, nightmare, and finally resolution. He concluded that such stories could be generalized along one of seven plots, each with their own psychological unpinning.6 Consider the use of conflict in each:

BOOKER’S SEVEN BASIC PLOTS

In addition to Booker’s seven, author Kendall Haven offers 12 story types, which he refers to as models.7

HAVEN’S STORY TYPES

| Historical | conveys a sense of resilience by looking back on a trial or tribulation |

| Who we are stories | highlight a group’s unifying characteristics |

| Teaching stories | utilize analogies to help people understand something new |

| Framing stories | set the stage for a presentation or new way of thinking |

| Future vision stories | create a compelling vision of the future |

| Wow stories | build appreciation by focusing on complexity, precisions, dedication, etc. |

| Struggle stories | outline struggles faced by a character on behalf of a noble cause |

| Relevance stories | concentrate on a specific issue with a short, tightly focused narrative |

| Put a face on it stories | make something abstract like a statistic seem real and personal |

| Values stories | present events that embody an organization’s or individual’s core values |

| I am you stories | highlight shared characteristics between a speaker and their audience |

| Ongoing stories | break a complex topic into parts; think TV series or pod cast |

Booker’s and Haven’s lists can be used to stimulate your own story ideas.

No matter the type of Story you’re developing, remember that it will need to garner the attention of your audience quickly. To do so, the audience needs to understand and care about what’s at stake from the very beginning. Recall the story segments from Chapter 1, Launch, Load, and Landing (page 13).

LAUNCH

The beginning of your story should quickly set in motion its events. Early on, you’ll need to get the audience to care, so offer story components such as: who is involved (i.e., the characters), what they are doing, why they are doing it, when they are doing it, and where it occurs.

Incorporate a few carefully selected sensory details so that the audience can imagine the situation for themselves. The key is not to provide too much detail. To determine what information to include, think about affective priming. In other words, what emotions does the audience need to have to prompt the change you are seeking? With this in mind, describe the scene in a way that evokes these emotions. For instance, if you want them to be angry about a problem, offer them details that are sure to fuel their angst.

The other important task of the story’s beginning is to pique the interest of the audience, which isn’t easy since attention is such a precious commodity. But remember by human nature, when we care about a problem, we want to see that it gets resolved. So, in the beginning, spark interest by highlighting an imbalance. Remember to offer a breadcrumb trail (see page 12) to build tension and the audience’s suspicion that something is amiss. Or start out with a bang, by describing an inciting incident that sets off a chain of reactions.8 The backstory highlights the events leading up to this incident, and expository scenes provide information about it, these elements work together to build interest and understanding.

THE ROLE OF PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

We are all plagued by the curse of knowledge from time to time. That is to say, our experiences bias how we see the world. This is because we call upon our prior knowledge, or what we know beforehand, to interpret new information and events.9 Similarly, an audience will use their prior knowledge to judge information. Author Ellen Lupton described this as “mapping familiar territory and charting the unknown.”10 In essence, stories act as “physical, visceral, and highly visual”11 metaphors since they symbolize familiar ideas and provide new information in a way that the audience can relate to. These relationships are indispensable as they can help the audience grasp unfamiliar concepts in vivid and tangible terms, and with emotional accuracy.

A metaphor can be established early in the story by grounding it in a universal truth that resonates with the audience (see page 23). In other words, wrapping your story around something that you know they will understand, because it speaks to the human experience. This will add to the relevancy of your message, and the audience will call upon this universal truth to judge any subsequent information that you may offer.

CHARACTER

Often, when we think about a story, we focus less on its plot and more on the characters who experience its events.12 That is, of course, only the case if we care about these characters. Similarly, an audience needs to care enough about a character to want to see their issues resolved.

While your characters don’t always have to be people, they should embody a few traits that will help an audience relate to them. Master storyteller Kendall Haven stated that compelling story characters must:13

Be a physical entity

Having a physical form makes them more relatable.

Be an individual

It’s easier to relate to one person than a group.

Possess the will and ability to act in their own self-interests

We need to know that they can act upon their goals.

Be able to communicate

We need to have insight into what they are thinking & feeling.

The longer the story, the more opportunities there are to express character traits. These traits can influence the audience’s attitude about the character, i.e., do we root for their success or revel in their failures?14 Yet, a character doesn’t always need to be real to be relatable. Fictionalized characters can be controlled, in that the storyteller scripts their reactions, but the risk is that the audience will see through these characters and grow apathetic about their plight. Real characters are obviously more relatable, but the question becomes, do they actually support the values that the storyteller is suggesting? At the same time, representing a mass of people with a prototypical character can be useful, but it can be difficult for the audience to relate to their more general characterizations. Finally, using yourself as a character can provide the benefit of instant relevance, but doing so can leave you feeling vulnerable and exposed to more intense scrutiny. So consider this tactic carefully. A story about a silly mistake you have made may be funny, but some audiences may judge you poorly after hearing it.

| Fictionalized | Real | |

| TYPES OF CHARACTERS | Pro: Can be controlled |

Pro: Relatable |

| Con: Audiences might see through them, & be less likely to care about their plight. |

Con: They might not always support the values of the story. |

|

| Prototypical | Yourself | |

| Pro: Represent many people |

Pro: Relatable |

|

| Con: They can seem inauthentic. |

Con: You may feel vulnerable and open to scrutiny. |

Recall that Jonah Sachs defined interesting characters as either “freaks,” “familiars,” or “cheats.”15 Freaks are captivating as they contradict our expectations; familiars remind us of ourselves or someone we know; cheats break the rules (either for good or bad). Going further, character’s built on Carl Jung’s archetypes can be used to frame the moral of the story,16 meaning that their traits can be used to represent the values you’re aiming to portray (See Chapter 1).

SACH’S CHARACTER QUALITIES,

based on Carl Jung’s archetypes

| Captain | Muse | |

| What values do these characters embody? | adventurous, confident, tireless, & brave | has faith in those around them |

| Key values wholeness, perfection, truth |

Key values beauty, richness, uniqueness |

|

| Negative traits can hold too tightly to their power |

Negative traits can be too passive |

|

| Pioneer | Rebel | Magician |

| bold, curious, & unafraid | creative, uncompromising, & driven to pursue justice | surprising, creative, & irreverent |

| Key values uniqueness, truth, richness | Key values justice, uniqueness, truth | Key values playfulness, perfection, beauty |

| Negative traits impatient | Negative traits easily mistaken for a criminal | Negatives traits can appear fraudulent |

| Defender | Jester | |

| driven to defend the vulnerable | intelligent but playful | What makes the character relatable? |

| Key values justice, perfection, wholeness |

Key values playfulness, justice, simplicity |

|

| Negative traits may be the last to accept change |

Negative traits can appear frivolous |

EXERCISE 3.0 CHARACTER STUDY

Write a paragraph answering the following questions.

Which character qualities from above do you most closely identify with?

How might your key values and flaws move a design story forward?

LOAD

The middle of a story helps the audience to vicariously experience its events. To aid this process, aim to provide context, define conflict, and share information during Load. When designing your story, ask yourself what “pictures” you want the audience to generate and recall. Then, what sensory details are needed to help them form these mental images? Aim to include a few details that appeal to our sense of sight, sound, touch, smell, or taste. These details can be scenic, in that they describe the setting of an event, or be event-specific, by recalling the thoughts, feelings, and motivations of the characters as they experience the story’s unfolding events. A design story might include a combination of these tactics to add richness and intrigue.

| Scenic Details | |

| TYPES OF STORY DETAILS | Use vivid words to describe the setting of an event. |

| Event-Specific Details | |

| Recount the thoughts, feelings, and motivations of the characters involved in an event. |

Whichever types of detail you choose, remember that they will be used by the audience as a substitute for their own observations. However, too many details will leave the audience buried and bored, so each detail should relate back to your central message. If this is proving difficult, the middle can actually be written after the Launch and Load segments since it serves as a bridge between the two.

EXERCISE 3.1 ADDING DETAIL

Determining the appropriate types and quantities of details can bring a dull story to life. Read the story below, and revise it by adding sensory, scenic, or event-specific details. Then share your version with another person to determine if you have added an appropriate amount of detail.

Despite her age, Gina was facing a number of health problems. These made even the most mundane daily activities difficult. Her fingers could barely move and her wrists ached. She knew that there had to be a better way to improve on some of her activities in the kitchen. After all, her family depended on her, and fast food wasn’t an option. So she picked up the cheese grater and got to work looking for a new form that might ease her pain and still allow her to provide healthy meals to her children. Many attempts ended in failure. Yet, she was driven. After nearly a year of trial, error, feedback, and revision, she was ready to share her prototype with others.

LANDING

When the audience has had the chance to become fully involved in the story’s events, their Landing can be either a hard or soft one. That is to say, you can end abruptly on a profound point or slowly bring events to a close. Either way, the story’s end should embody the moral you’re aiming to convey.

Many designers don’t offer this type of closure, instead opting to pivot their audience’s attention toward their design outcomes prematurely. This can leave the audience feeling like the story is unresolved, which can be a missed opportunity since the story’s resolution can play a central role in prompting the audience change you are seeking.

Author Kendall Haven has explored the link between a story’s resolution and the audience’s emotional state, calling this Residual Resolution Emotion (RRE).17 He posited that an audience is deeply affected by their emotional state at the end of the story – whether they are feeling upbeat or downtrodden. Haven refers to these as positive or negative RREs. While they each affect audiences differently, he asserts that both are influential. He was led to this conclusion after studying the reactions of multiple audiences to different stories.

THE INFLUENCE OF A HAPPY ENDING

Haven found that stories with a powerful happy ending, i.e., those that were considered eye-opening, gripping, inspiring, impressive, commanding, powerful, heroic, or life-altering, have little immediate effect, but can have a long-lasting impact.

Yet, he found that the most influential positive RRE stories aren’t the result of an entirely rosy scenario for the character. In fact, the character still faced turmoil and conflict. Haven suggested when the audience identifies with the main character and sees their success, in the end, their takeaway is “I should do the same thing, should a similar opportunity arise.” Thus, they may not act immediately, but when the time is right, they will be more likely to undertake the same actions as the character. However, this implicit message hinges on audience’s involvement in the story. The best way to ensure their involvement is to leave a little bit of doubt that the character will resolve the problem. That is to say, the character struggles. Without this sense of the character’s struggle, the path toward resolution appears too easy, and thus the audience is less likely to care.

THE INFLUENCE OF A TRAGIC ENDING

Haven also found that negative outcomes can be effective in prompting audience change. Stories described as abhorrent, heinous, loathsome, despicable, detestable, outrageous, atrocious, or intolerable created a demand for action from the audience. Haven suggested that it was as if the audience was driven to change the outcome of the story.

LEVERAGING THE STORY’S ENDING

If your goal is to have the audience do something quickly, negative stories can stimulate a “call to action.” In fact, the more distressing the story’s resolution, Haven wrote, the greater the tendency for that audience to take immediate action (i.e., donate, protest, boycott, etc.) – “It is as if they feel compelled to correct the situation.”18 So, keep your goals in mind when determining your character’s fate.

CHARACTER CHECKS

Haven offered some checks to help storytellers understand the possible effect their story’s characters will have on their audiences.19

| CHARACTER CHECKS | Determine which character the audience actually identifies with (it may someone other than your protagonist). How bad (or good) is the story’s ending for that character? Who is blamed (or rewarded) for that ending? |

You’ll want to ensure that your audience will identify with the intended character. You may be surprised to learn that they are more likely to identify with someone other than your main character. If so, revise your story to make your protagonist more prominent or relatable. Remember that if your goal is to evoke an immediate response, the ending should be bad for this person. If your intent is for a more sustained response, then the story’s resolution should be good for this character. This way, the audience will want to mimic the actions of the protagonist, so that they too might enjoy the same outcome. Finally, make certain that the right foe is being “blamed” for a negative outcome. For instance, if the main character is an employee struggling to be productive despite working in a poorly planned office environment, the blame for his struggles should be placed on the environment and not some irrelevant foe, such as an unreasonable boss. On the other hand, if the outcome is positive, you’ll want to make sure that the main character is credited.

STORYBOARD

Part organizer, part archivist: a storyboard is a vital tool in storytelling. When working on a storyboard, start broad, thinking of the overall story. Then add sub-themes and details as they become known.

Figure 3.3

Storyboards start broad & details are later added

THINGS TO AVOID IN STORYTELLING

“There are only three rules for creating great stories … unfortunately, nobody knows what any of them are,” wrote Haven.20 While we know there is no one “right way” to move through a story, established storytellers do provide some tips as to what a storyteller should avoid.21

| Bragging | An audience would rather hear about their successes than yours. | THINGS TO AVOID |

| Using Jargon | Be sure to define unfamiliar terms. | |

| Talking at the Audience | Illustrate with sensory details, but let the audience make their own conclusions. | |

| Exaggerating | Do not claim a story is true if it is not. | |

| Being Impersonal | Avoid intangible statistics. Instead, personalize a story with one central character. |

AIDING RECALL

If you have managed to change the beliefs and actions of the audience, you will want to ensure that they will remember this change. To do so, consider how to help your audience members remember your message.

LEVERAGE A LOGICAL SEQUENCE AND SERIAL POSITION EFFECT

The audience is more likely to remember the first & last parts of a message.

Tip: Orientation is important. Ensure that the audience is connecting pieces of information as they should.

Example:

A designer may include a table of contents or verbal guide on what they will cover.

HELP THE AUDIENCE DRAW CONNECTIONS

Help the audience connect new information to familiar ideas.

Tip: Consider the use of metaphor.

Example:

A designer may refer to a hospital’s design as being “like a mountain spa.”

MAKE THE AUDIENCE WORK

Having the audience work provides them stimulus & opportunities to think for themselves.

Tip: Ask the audience questions and pause for reflection.

Example:

A designer may ask an audience to think about their first experience with a product.

EXERCISE 3.2 EVALUATING STORIES

Think back to your favorite book or movie.

Can you identify the character qualities of the protagonist?

Does that story have a clear beginning, middle, & end?

HOW TO COLLABORATE

Remember the adage, “Two heads are better than one”?

Similarly, collaboration can result in better story ideas and more thoughtful presentations. While the benefits of collaboration are many, it can be a difficult process.

To manage collaboration, consider the following:

Try to work in close proximity

Teams that play together, stay together

Identify formal or informal leaders |

Accept that conflict is inevitable, but not necessarily bad

Hear and be heard |

SUMMARY

Designers use both stories and “S”tories. Presentations themselves are stories, while “S”tories can help make your ideas come alive.

Designers may find themselves crafting stories that speak to their own points of view, highlight a key project, or pitch for a potential opportunity. The design of these presentations is similar to that of the design process. In both, the early stages are marked by a multitude of ideas. These ideas are mined to unearth a central theme, which is akin to the values of your message. To hone your message, examine how your themes and sub-themes align with your goals and the characteristics of the audience – especially when it comes to how the central message prompts the desired change. The arrangement of the themes and sub-themes, also known as the sequence, should be considered holistically, wherein the overall structure is determined prior to deciding specific details.

“S”tory

To make the presentation relatable, overlay aspects of Story to pique audience interest. During your Story, provide sensory details to help the audience build mental images. Be sure to offer them a character they will care about. The Story’s resolution can influence the audience. Research suggests that strong positive stories elicit delayed, but long-lasting responses, whereas negative stories compel the audience to a more immediate action.

Recall

After all of this effort, you’ll want your audience to remember your message, and they are more likely to do so if:

• information is arranged to leverage serial processing,

• ideas are presented relevant to their prior knowledge,

• they have a chance to reflect on it or work toward a solution.

TERMS

prior knowledge

APPLICATION 3.0

As you develop your presentation further, consider the following:

1 Based on your goals, answer questions in the point of view, project, or pitch sections (see pages 35–37). Remember to ask “why” to your answers to unearth their deeper

2 Explore how your answers represent common themes, the most prominent of which becomes your central theme. Remember, the aim of this central theme should harken the change you are seeking from the audience.

3 To develop sub-themes, explore the answers to your questions alongside your content (e.g., project deliverables). Look for patterns and any potential alignment to the central theme.

4 Using your sub-themes, explore the most appropriate sequence for the presentation (see pages 40–42).

5 Then develop a Story that represents the values of this central theme. Consider how this Story should be woven into your presentation. How do the characters embody the values? How might the audience relate with the characters? Are there any metaphors that would make its events more relatable?

6 Using your answers, conceptualize your overall presentation below.

| Launch Introduction |

Load Middle |

Landing Ending |