![]() CULTURAL VARIATIONS

CULTURAL VARIATIONS

Application: International Marketing

The Concept

People in different parts of the world have different languages, mindsets, preferences, attitudes, and prejudices. This “collective programming of the mind”, the inculcation of indigenous culture, occurs during childhood and adolescence; and different cultures create different expectations and attitudes in customers. It is often so subtle that people themselves can be unaware of their own cultural perspectives and biases. Yet it has a profound effect on their attitude to life and business. While another country may look misleadingly similar to home territory, there are underlying attitudes to life and business that mean different criteria are used to make judgements. These differences in lifestyle, values, behaviours, and business practices between different geographies and cultures are difficult to identify, digest, and manage. While stereotypes and clichés are often exaggerated, there are genuine differences in taste and approach, which can cause real problems. This is a marketing issue because some products and services are intensely personal and affected by imagination, aspiration, allegiance, atmosphere, intonation, or body language. Cultural differences can affect their success in different countries or regions.

Language is an obvious example. When Coca-Cola first started serious international expansion, for example, it had difficulties with its name alone. The Chinese characters which most closely reproduced the sound of the drink’s name actually translated as “bite the wax tadpole”; whereas their slogan (“Refresh yourself with Coca-Cola”) translated into Dutch as “Wash your hands with Coca-Cola” (see Pendergrast, M., 1993). Although English is now generally accepted to be the international language of business, different words have different meanings and the subtlety of intent can be lost in translation. However, they are even more likely when a supplier is working, through translation, in a customer’s local language.

Even worse, culture and upbringing give different meaning to words which can dramatically affect understanding. Problems can be caused through the ignorance of cultural differences. For example, while the English word “lunch” refers to a meal eaten in the middle of the day, what this signifies varies enormously in European cultures. In Sweden, it is generally a meal at 11:30 am which comprises fish, potatoes, and salad accompanied by a “lättöl” (a light beer). To the English, though, it means a snack, like sandwiches, eaten soon after midday, generally at the desk, or possibly, in the pub. To the French, particularly in Paris, it is still often a three-course meal at 1:00 pm with red wine and, to the Spanish, a big meal at 3:00 pm. The cultural context gives different meanings to the word, complicating life. If an inexperienced Swedish business person says to a Spanish customer: “we’ll discuss this over lunch”, obvious complications arise. Cultural heritage has an enormous effect on marketing because words are given very different meaning by their cultural context.

Even the ubiquitous American fast food service, McDonald’s, has to be customized in different cultures of the world to deliver satisfaction. Although it is thought to be the same the world over, the franchise dynamic of the firm’s international operations has not only ensured that the service is varied around the world but also that the fast food menu itself is customized to some degree. As John Travolta’s character pointed out in the film Pulp Fiction, their products in Paris (and other countries) are different to those in the USA. But there are other aspects of the service that have been adjusted over the years. For instance, in the early years of its expansion into the UK, their employees were trained to say “Have a nice day”. In America this is a polite, unremarkable phrase, which is part of day-to-day life. However, this was not natural to employees in the UK and their uncomfortable tone of voice implied insincerity. Unfortunately, as one of the key service assumptions in the UK is sincerity this caused offence and affected trade. (British people will tolerate many other aspects of poor service if the service supplier is sincere or polite.) Eventually, McDonald’s publicly apologized to the country through PR and mass advertising media; and dropped the phrase.

What is not often understood is the vast difference that cultural heritage makes to quality expectations. “Quality” to a New Yorker, for example, can mean choice and speed of delivery while to the English it means sincerity and to Germans, thoroughness or accuracy. People approach every service with a set of expectations, which are both emotional and practical. They will only think that a service is good quality if both the technical content and the service performance meet those expectations. Yet they will not make any effort to explain these expectations and, in fact, are often unaware of them themselves. However, they are ruthless in the way they criticize and judge a firm if it does not meet these articulated and unarticulated expectations.

So, cultural differences force a company to consider the customization of service to meet local, cultural expectations. This has serious implications. It may be that, in one culture, the delivery of service is a performance designed to serve the customer with people and take care of all of their needs. In another, however, excellent service may be self-service. In yet another, it may be delivered through advanced technology. So, if a marketer is designing a service that will be received in Scandinavia, Germany, Spain, and France, they need to research the expectations of that service in each of those cultures. The outlook, attitude, and assumptions will be different in each culture and the service must be adjusted to suit those different tastes.

Firms both large and small have been damaged by ill conceived international strategies. Marketers should think through the strategic and managerial aspects of international market approaches with real care. For instance, culture affects demand for different offers. Some cultures, for instance, value strategy and consultancy more than others. The Nordic countries of Europe tend to place emphasis on discussion and debate that leads to consensus. This, in turn, tends to make them value ideas and pay for advice more readily than, say, the British. As a result, the demand for a consultancy service, and the price people are prepared to pay for it, is different in different cultures of the world.

It is often wrongly assumed that, in business-to-business markets, attitudes and expectations are very similar across the world and, as a result, cultural differences are less important. However, there is much evidence that differences occur and affect all aspects of business. One of the most useful and extensive studies to demonstrate this was undertaken by Geert Hofstede (Hofstede, G., 2001). He identified five significant cultural variations and devised matrices by which international business affairs can be planned and managed. Interestingly, his original research was conducted in one business-to-business company (IBM) that perceived itself as a successful market leader with one consistent global culture. So, even in the perceived monoculture of one large international business, cultural variations have a large influence. This has implications for many aspects of business-to-business practice.

In fact there is very little business practice that is not influenced by cultural diversity and, as a result, impacts the markets of suppliers. For instance, different cultures respond differently to colour and this affects any work on international design, advertising, and brand. Similarly, there are indications that business innovation occurs differently in different cultures so that the styling of propositions needs to be adapted. Finally, there appears to be a difference in the adoption of new ideas, affecting the pace at which new offers are launched and accepted by the market in different parts of the world.

History, Context, Criticism, and Development

Market-led companies have been working on the international stage and dealing with cultural variations for many centuries. As late as the mid 20th century, though, the attitude to international marketing amongst marketing theorists and teachers was from their home country out to the rest of the world. A groundbreaking piece of work was undertaken in the 1980s by Geert Hofstede. He researched, developed, and published a number of dimensions of cultural difference. He grouped, tested, and demonstrated the effect of these dimensions on management practice. They can be used to guide international strategy and planning.

The dimensions were:

(i) Individualism versus collectivism. Some societies are loosely knit, where individuals are supposed to take care of themselves and their immediate families. Work, career, economic provision, and progress are centred around the individual. Others are more collective. Individuals can expect their relatives, clan, or gang to look after them in exchange for loyalty.

(ii) Power distance. This is the extent to which members of a society accept that power in its institutions is distributed unequally. This attitude affects the behaviour of those with and without power. Large power distance cultures accept hierarchical order in which everyone has a place; small power distance cultures strive for equalization. This issue affects how societies handle inequalities when they occur.

(iii) Uncertainty avoidance. This is the degree to which members of a society feel uncomfortable with risk, ambiguity, and uncertainty. Uncertainty avoidance cultures maintain rigid codes of belief and behaviour. They are intolerant towards deviants. Weak uncertainty cultures are the opposite.

(iv) Masculinity versus femininity. In Hofstede’s view, masculine cultures prefer achievement, heroism, and material success. Whereas feminine cultures stand for relationships, modesty, caring for the weak, and quality of life.

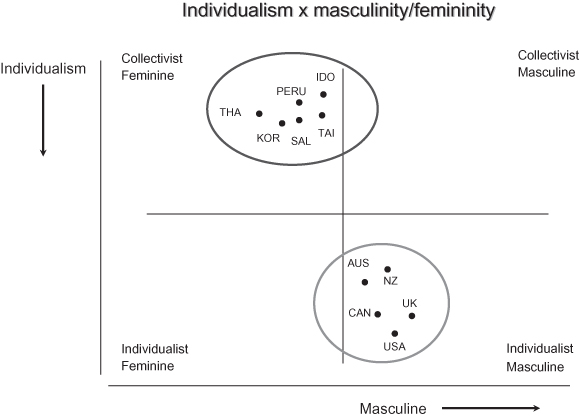

This work shows how different cultures cluster and are similar under different dimensions. Figure C.6 represents just one set of pairings (individualism/collectivism with masculinity/femininity). This clearly shows the clustering of the “Anglo Saxon”-influenced cultures of the USA, UK, New Zealand, and Canada. A proposition built on the assumptions of individualistic masculinity (like high-end executive search) is likely to succeed in this group. The model can be used as an aid to almost any international marketing function. It can be used to develop growth and acquisition strategy. It readily reveals compatible cultures that will be low-risk targets. It also shows how communications and product or services need to be adapted to penetrate different cultures.

Figure C.6: A representation of Hofstede’s cultural variation models

Voices and Further Reading

- “Since marketing is part of the social warp and woof of a nation, it is essential to understand all aspects of a people’s culture in order to appreciate the structure of their marketing systems and operations. Customs, language, religion, taboos, ethnic relationships and dispositional characteristics can significantly add to the professional insights of the marketer.” Carson, D., 1967.

- Fifield, P., “Managing the mix in Europe”, in Perspectives on Marketing Management, vol. 1 Chapter 5, edited by M.J. Baker. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Hofstede, G., “Cultural dimensions in management and planning”. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, January 1984.

- Hofstede, G, Cultural Consequences. Sage, 2001.

- “Outcome control systems are much better received in some cultures (such as the United States, Canada, Argentina, Italy, Southern Nigeria or parts of India) than in others (such as Sweden, Japan or Korea). A firm with global reach, therefore, should have multiple control systems for its various sales forces”. Anderson, E. and Onyemah, V., 2006.

- “In Europe, most of the evidence points to the fact that cultural differences persist in playing a decisive role in forming our consumption patterns and our unique expressions of consumption. At the same time, global competition tends to have a homogenizing effect in some markets such as music, sports, clothing, and entertainment … Cultural borders do not always follow national borders. Although national borders are still very important for distinguishing between cultures, there may be important regional differences within a country, as well as overlap between two countries. Add to this immigration and the import of foreign (often American) cultural phenomena and you begin to understand why it is very difficult to talk about European countries being culturally homogenous.” Solomon, M. et al., 2006.

Things You Might Like to Consider

(i) Cultural variations exist between regions within geographic boundaries. The differences between the regions with countries like, say, Spain, Italy, and the United States of America can be large and profound. So, it can be dangerous to assume that a nation responds with unanimity to an offer.

(ii) The majority of the fans of British soccer team, Manchester United, are not in Britain or even Europe. Remarkably, a wide range of people in Asia are devoted followers, keeping up with their team’s stars and tournament performance through satellite TV. Despite living in the heat of Singapore or Malaysia, in perhaps poor circumstances with Muslim beliefs, many people are part of an excitable group, which charts the course of rich, pampered Western soccer stars. They suspend their cultural heritage and issues for a greater benefit: to be part of an excited tribe. A similar phenomenon occurred just after the Second World War. At the time, America was seen as energetic, modern, and rich. People across the devastated globe wanted to feel part of its exciting modernity. They wanted to belong and, as a result, willingly bought into American exports like Coca-Cola with its promise to a young generation. It is possible, then, to create an offer that has appeal and fame across the world. It is so associated with success that it prompts people to desire it and suppress or suspend their cultural predilections. They want to get in on the experience.

(iii) Is the world truly global in the sense of creating ubiquitous, similar offers? It is certainly very integrated, with formal trading treaties, regional trading blocks, and a growing consensus amongst political representatives. Yet, for the past 3,000 years the thrust of history has been driven by the rise and fall of great powers. At the time of writing, China and India are in the ascendancy. How much is international marketing strategy to be developed within the constraints and opportunities of the evolving nature great powers? Is the world really stable, integrated and “global”?

(iv) The safety created by the evolution of regional entities, like the EU, seems to allow local culture and identity to reassert themselves. And, cultural identity is very powerful and durable. There is, for instance, an annual meeting and celebration of Celtic culture. People travel from Wales, Cornwall in the UK, and parts of France to share music, art, and poetry in common languages. What is remarkable about this enduring cultural identity is that the Celts were largely wiped out some 2,000 years ago. Their sense of community and identity has, it seems, endured and is growing in strength. The same can be said of many cultural groups. So, is bland international sameness really appropriate with a rise in cultural identity?

(v) When business leaders talk of globalization they often use this as shorthand for the world’s centres of capital (like New York, London, and Hong Kong). Is the company’s ambition really global or focused on some tighter international grouping?

(vi) It is remarkably difficult to identify your own cultural values, beliefs, and prejudices.

Fujitsu Evolves into a “Transnational” Enterprise to Grow Its Global Business

Japanese IT giant Fujitsu is a leading provider of IT-based business solutions for the global market place. With approximately 175,000 employees supporting customers in seventy countries, Fujitsu combines a world-wide team of systems and services experts with highly reliable computing and communications products, and advanced microelectronics, to deliver value to their customers. Headquartered in Japan, with revenues of US$47 billion, Fujitsu is the world’s fourth largest IT services provider and Japan’s market leader.

TIME FOR A NEW GLOBAL BUSINESS STRUCTURE

Global expansion is on of the agenda of most large enterprises, together with how best to organize themselves for international operations. Developing a new strategy-structure relationship in the increasingly complex environment of international business is an enormous challenge. Yet it is one that Fujitsu has taken head-on in order to achieve its aim of becoming a truly global IT company, based in Japan, within a three-year (FY2009–2011) timeframe.

Fujitsu recognized that it needed to adopt a broader, global perspective, rather than focusing so heavily on Japan, and has undertaken a radical shift in the focus of its operations. The process of structural reform has meant an end to a “silo approach” to business inside and outside Japan, with integration enabling the Group’s companies to work together better to accelerate global growth. The strategy to clarify responsibilities and strengthen overall group management is reflected in its adoption of a “transnational organisational model”. This reinforces Fujitsu’s ability to view operations from a global standpoint, while still pursuing business that is responsive to the prevailing conditions in each region, taking customer-centric management to a new level.

President Kuniaki Nozoe explains, “We will expand business globally by leveraging the base Fujitsu has built in developing its worldwide operations over many years, and by instilling the maxim ‘Think Globally, Act Locally’ in our operations.”

Two business imperatives drove this strategic change in organizational structure. First and foremost was the need to organize the group’s business to better meet the needs of its global markets and clients. This involved improving its ability to: present a “One Fujitsu” to all customers; to take products and services to market together; to simplify its regional organizations; and to derive lasting benefits from best practice and standardized processes across regions. Second, naturally, was future growth, and the opportunity to significantly increase the percentage of Fujitsu’s business outside the Japanese home market.

The expanding global IT market place, where markets are developing at different speeds and in different ways, is driving this increasing demand for both global and local excellence. In IT services, analysis of consumer wealth and IT spend shows the considerable variations and opportunities, (particularly between markets in the West and newly emerging economies). As these markets evolve quite differently, so local requirements vary from market to market, despite the fact that clients also demand the benefits of global scale and coherence. It was the need to address this paradox of “trying to do it all” that was behind Fujitsu’s move to become a transnational enterprise; “thinking globally and acting locally”. With few truly global IT companies, and none that are wholly successful, Fujitsu saw the potential for differentiation through this approach.

Fujitsu has long worked to develop operations globally, and was one of the first IT vendors in Japan to advance operations abroad. Fujitsu Services, for example, had an impressive track record in securing large-scale outsourcing business deals in Europe. But despite this record, and initiatives such as their “Global Service Innovation Programme”, Fujitsu’s operations outside Japan were limited to an “Act Locally” mindset.

Pressures for local responsiveness or for global integration lie at the heart of the international strategy-structure choices considered by Fujitsu. They reviewed four models – Multi-national (ultimately localized), Global (highly centralized), International (focused on sharing), and Transnational (highly networked) – which differ according to their management structures, external approach to the market, and internal lines of communication and reporting. The Transnational organization combines the essential features of the other three models. It is flexible and sensitive to local conditions (like a Multi-national company), competitive and efficient (like a Global company), and, at the same time, attentive to sharing knowledge across local business units (as in an International company).

So, seen as the answer to increasing complexity, the transnational model is a balance between the pressures for global integration and for local responsiveness; centralized control and decentralized autonomy. Described by Fujitsu as an “integrated network”, it can deliver simultaneous efficiency and scale benefits for global competitiveness, national responsiveness for flexibility, and the benefits of corporate-wide learning for innovation. As a pure form it is still evolving, but it seemed the obvious route for Fujitsu given the group’s multi-national heritage, global aspirations, and unique culture in the world of IT services and solutions.

Fujitsu is now fully embracing the management principles behind the transnational business model. A structural reform is underway, that underpins the global delivery of a “One Fujitsu” to all customers; going to market under one consistent brand, with one single business responsibility. Whereas the “local” component that is the company’s heritage helps to simplify and transform their regional operations, providing empowerment but not independence. Global coherence has evolved from a small but powerful set of functions, all supported by a shared incentives programme called the “collective bonds of performance”.

Clients undoubtedly benefit from the “Think Global, Act Local” approach. The scale and coherence of the transnational business elevates Fujitsu’s global delivery and global client management capabilities. The shared values of the “Fujitsu Way” reinforce the “One Fujitsu” experience. Whilst, the global knowledge and experience-sharing add considerably to the security and confidence that is a function of scale and reach.

At the same time, the local proximity of focused regional operations helps ensure Fujitsu is fully in tune with local market conditions and client requirements. For example, it enabled the successful roll-out of a client relationship initiative, “Field Innovation”, which converts IT innovation into real business value. Long-term partnerships are also more manageable.

Fujitsu believes the transnational model works well to balance global scale and local touch. From their experience, it’s now feasible to reach the higher number of services, sectors, and geographies on a “global” level, yet with the “local” benefit of greater segment focus and more localized management and delivery systems. Another advantage includes a superior ability to meet key IT purchasing criteria. These include building a deep understanding of the customer’s requirements; getting senior executives involved in the sales and delivery process to build relationships and demonstrate commitment locally; pricing competitively at both a global and local level; bringing all the benefits of a tried and tested solution to bear for the customer; and having the scale and flexibility to offer innovative, outcome-based commercials.

Fujitsu continues to push ahead on structural reforms and growth strategies geared to each market while strengthening group management, clarifying responsibilities, and increasing sales. Where previously each region implemented their own strategy, with significant overlapping of functions, now there is unified planning. R&D, sourcing, and supply chain have become “global” integrated functions, with sales and service positioned squarely at the “local” level – Japan, the Americas, APAC, China, EMEA. Taking “Think Global” a step further, the Global Business Group that drives strategy has been organized into four global support functions – namely, Marketing, Delivery, Global Client Management, and Business Management.

The specialization of Group companies has been a major component in the restructuring. Concentration of resources has put Fujitsu in a stronger position to better meet the needs of business markets of all sizes. Converting Fujitsu Business Services into a wholly owned subsidiary, for example, effectively created a one-stop shop for medium-sized businesses in Japan. The acquisition of Fujitsu Siemens Computers, was a catalyst to accelerate the Group’s globalization strategy. Through reorganization of this subsidiary, and further realignment of operations outside Japan, Fujitsu aims to double annual IA server sales within two years, and to improve profitability in the longer term by adding services to these deals.

Fujitsu’s global value proposition has evolved noticeably alongside the structural changes. An ambitious transformation that is paying dividends, with the cost efficiencies, strengthened management structure and integrated “Think Global, Act Local” capabilities of a transnational enterprise fast being realized.

President Kuniaki Nozoe confirms: “Fujitsu’s goal is to get more than 40 per cent of its sales outside of Japan in fiscal 2011, and it will do this through a ‘think globally, act locally’ strategy.”