![]() SERVICES MARKETING

SERVICES MARKETING

Application: All Marketing Activities in the Service Sector

The Concept

This concept suggests that the methods to create, run, communicate, sell, and grow a service business are different from those used to handle a product business. The major differences reported by marketers working in the field and by researchers who have studied it are as follows.

(i) Intangibility

Pure services are intangible. They have no physical presence and cannot be experienced or detected by the five senses. So it is not possible to taste, feel, see, hear, or smell them. As a result, they are communicated, sold, and bought in the customer’s imagination.

This lack of physical components affects marketing in several ways, the first being pre-purchase assessment. Human beings seem to need physical clues to help them assess benefits and compare value propositions. People find it hard to accept or engage with a concept until it is reality, presented to them in physical form. They need to see it and touch it to understand it. In fact, the comparison of physical elements (in a new car for example) often clinches the sale. So, potential customers of a service business need help if they are to understand and grasp the offer. When buying an intangible service, they will often seek the opinion of people they respect before purchase and will buy again only if their initial experience of the service is good. So the reputation of the service, the quality of the experience, and the appeal of the packaging are all very important. The supplier needs to make its intangible service seem both tangible and testable.

Some service marketers create sales promotion materials that represent the service. For example, a recent trend in the retail market is the sale of “experiences” as gifts. People can buy days at spas and race tracks for others. These services are sold in attractive packages which can be displayed on promotion racks and easily taken, by the buyer, to tills. In business-to-business markets there have been similar packaging attempts. Over the past two decades, for instance, a number of the leading IT firms have offered their maintenance and project management services in attractive, packaged form. Even leading professional service providers, who generally detest the idea of their service being “marketed”, use collateral in the form of expensive brochures and case studies to convey the spirit and skill of their offer. Packaging and promotion are therefore one of the prime communication tactics used to market intangible services; to make the intangible, tangible.

More important, though, is the need to understand and emphasize the buyers’ experiences of an intangible service. Just as people want to understand how a product might work in practice, they need to understand what their experience of a service might be; and this should be an important focus of service marketing. When launching a new service, for instance, many suppliers create ways to encourage potential buyers to take part in free trials or test runs. They are an essential part of the launch. Some famous hairdressers, like Vidal Sassoon and Nicky Clark, started their remarkably successful franchises by giving free service to celebrities and other opinion formers.

Once the buyer has experienced the service, they are in a good position to assess it for their own future needs and, just as importantly, for the needs of friends or relatives. So, free trials overcome many of the difficulties caused by intangibility because they reduce the perceived risk of purchase. They are also a way of starting one of the most important service marketing tools: word-of-mouth (see viral marketing). If customers have a good experience they will talk about it to others and the reputation of the new service will begin to spread. (A bad experience, by contrast, will create negative stories that undermine any effort to grow the business.) After launch, the most important marketing strategy is to amplify this natural reputation. It can be captured in testimonials or printed case studies but it is most effective when word-of-mouth is amplified through viral marketing.

Also, as there is no physical product, sales people cannot emphasize benefits but must communicate the experience and outcome of the service process. The selling of an intangible service must therefore be very different from the selling of a product. In fact, if the routine closing techniques of product sales are used to clinch service deals, due to intangibility, the buyers tend to feel coerced or cheated and, as a result, might challenge the price or have second thoughts. In some cases, the deal can unravel altogether.

The intangibility of services exaggerates “post purchase distress”. So, marketers dealing with services have to ensure that they develop techniques by which they mitigate it. Many put emphasis on good after care and others produce printed examples of previous contented buyers; these are given to new buyers soon after purchase. Both provide valuable reassurance.

Finally, as it is often not possible to patent intangible services, suppliers have to find other mechanisms to protect their investment. Failure to do so will mean that services commoditize quickly and markets will be dominated by price wars. Successful service companies therefore create powerful brands which cannot be copied. Some companies that are not skilful at brand creation and management, like some in the IT industry, have damaged their business by moving into service with very little means of maintaining differentiation.

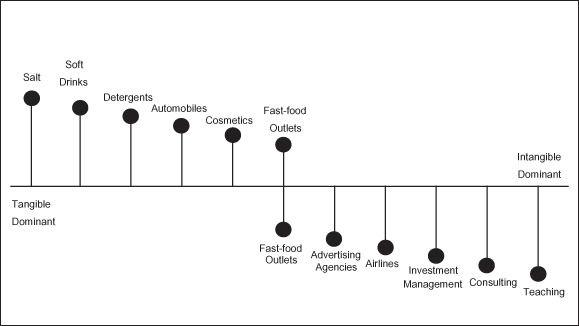

Yet, as with a number of the differences between products and services that are proposed by academics, there are “shades of grey” which complicate life for marketers. (Lynn Shostack captured this in her product/services spectrum shown in Figure S.3). In a number of services, for instance, there are physical components which mitigate the effects of intangibility. It might be that the service itself exists to support a physical product (as in the case of a maintenance service) or has important physical components (like the seat, cabin, and meal in an airline service). These can be used in the marketing of the service to help underline its benefits and overcome buyers’ fears or hesitations. They are tangible manifestations of the intangible service and can be used as marketing aides. As a result, airlines will advertise the seat or the meal, and consultancies their people.

Figure S.3: Shostack’s continuum of products and services

In fact, despite academic assertions that intangibility fundamentally changes marketing, there can be little difference in practice between the marketing of product-based services and the marketing of some products. Many products are a mix of physical, conceptual, and service components. A washing machine, for example, is bought because of its functionality, the physical components, the design, the brand, and the service support package. It is also bought through the service system of a retailer. So, the white goods industry has learnt to offer extended warranty as part of product purchase, maintaining total return from the product line through service margins whilst actual product prices have fallen. Although the warranty service is intangible, it is presented as any other retail concept tied to a major product purchase.

Moreover, the marketing industry already has great experience in communicating conceptual, intangible offers. Most brand managers in successful consumer goods companies, like Unilever or Procter & Gamble, would argue that they are in the business of making intangible offers; that a branded product is a concept offering valuable intangible benefits to buyers. A product such as Heinz Baked Beans is, for example, a combination of: haricot beans, sauce, packaging, easy distribution, image, and consistency of familiar taste. It is tangible in the sense that it contains physical components that customers can eat but enormous value is created for Heinz by careful management of the intangible brand concept. Over years the company has invested time, money, and skill in building the brand in the minds of a group of customers. As a result, there is a heritage and equity that causes customers to buy repeatedly at higher prices. So, in order to tackle intangibility, marketers should imitate many of the successful techniques of branded goods such as: excellent brand management, positioning, packaging, and progressive investment in fame.

(ii) Variability (or Heterogeneity)

Once a product has been designed and the manufacturing process set up, it will be produced time and again by a factory with little variation. Customers know what they are buying and it is consistently delivered. Any aberrations in product quality tend to be few and easily (or relatively easily) driven out by quality control and improvement processes.

Services, though, are rarely as consistently produced as manufactured products. Even those service businesses that try to “industrialize” (see Levitt, T., 1972) their offer through efficient and robust processes find it hard to deliver reliable, consistent service every time. For instance, one of the essential components of many services is the people who serve customers. But people tend to think for themselves, adjusting behaviours and outcomes to suit unique circumstances. Moreover, in certain cases, customers are involved in the process of service production. As people take initiative and change or customize the service, it is unusual for one service experience to be identical to another.

This has implications to the way services are taken to market. For instance, people need to be given clear guidelines on how much they can vary the service. Some businesses want little variation and give their employees little discretion. Others, “mass service shops” like Burger King, for example, see competitive advantage in allowing a degree of customization but are aware that too much will damage the economics of their business. So, marketers need to specify processes which streamline as much as possible but allow people to vary delivery and anticipate failures. They also need to set expectations and communicate the degree of consistency that customers might expect. Their main tool in this is their brand because it sets expectations of a standard of quality. Consumer brands like easyJet and business brands like Accenture, set different expectations. The brand positioning, for example, attracts different buyers. A cut-price airline will not be expected to provide high quality food or good landing access to the heart of key cities, whereas the service experience from Accenture’s consultants must be as excellent as the business outcomes they offer.

One particularly powerful brand strategy, which sets expectations to suit service variability, is to introduce an element of humanity or responsiveness, which acknowledges that errors might occur. Many high volume consumer services emphasize in their advertising that buyers should complain, if errors occur, so that they can be quickly put right. The Virgin organization, for example, grew through a commitment to contemporary service, which was prepared to be avant garde while promising that any human errors would be remedied well. Their humour and humanity, embodied by their brand icon Sir Richard Branson, ensured that buyers were unconcerned by minor quality errors.

Branded volume services use advertising and signage in their premises to signal their intent to provide as consistent and as reliable a service as possible; but also to redress any errors. Some show examples of the processes or systems they use to produce the service. Others use practical documents, like a railway timetable, to set expectations of delivery. As important, though, is the appearance of the service and any physical elements in it. The design and cleanliness of trains and the uniform of employees, for instance, must be carefully managed. A run-down, scruffy service creates entirely different expectations to one which looks organized and professional. A volume service which is clean, reliable, and well packaged will be more readily forgiven for unusual and minor inconsistencies.

At the other end of the scale, the prime mechanism by which professional services, like law, try to achieve consistency is through the recruitment and training of people who will deliver a certain quality and style of service. The delivery of the service might be highly individual and customized to a client’s unique situation, but the style of service and manner of delivery must be consistent. Young professionals are schooled in both the technical skills of the firm and its approach to business. Many practices have rigorous control procedures and detailed ethical guidelines that attempt to deliver consistent standards. Yet the heart of their business is the recruitment, development, and motivation of high quality “human capital” which, without close supervision, will deliver the style of service that reflects the firm’s position in the market. As a result, the main device used by leading professional service firms to obviate heterogeneity of service is their investment in sophisticated and consistent recruitment marketing aimed at graduates from leading universities.

Other attempts to handle variability include the nature of the contract and guarantees about quality standards, offering financial compensation if errors occur. Excellent, responsive post purchase customer care is also seen as essential to the effective marketing of variable services and forces marketers to focus on quality of service, service experience, and service recovery.

(iii) Simultaneous Consumption

A product can be manufactured and stored or passed through a distribution system until it is bought. Once bought, it can then be stored by the customer and used at a later date. By far the majority of services, however, have to be used as they are created. They cannot be stored by either the supplier or buyer. In order to deliver, resources must be prepared and deployed ready for erratic demand. A maintenance service, for instance, must have computer systems able to receive fault reports, trained technicians with appropriate tools able to tackle technical difficulties, and carefully calculated caches of spare parts. Moreover, much of this investment is unseen by the customer before, during, or after the service experience. This means that service companies need to develop techniques that communicate the value of this stored investment.

Simultaneous consumption also means that marketers must focus on demand forecasting and demand management so that resources are available when needed by buyers. They frequently use statistical modelling techniques to predict likely demand based on previous purchase patterns. Some, though, work with key buyers to share the risk of demand fluctuations while others try to influence demand by different pricing patterns. The airline industry, for example, uses different ticket types to get commitment to purchase weeks in advance. In many cases they over-book flights, using incentives to get some passengers to change their flight if necessary. Some marketers also seek to communicate the extent of their stored infrastructure as an asset at their customer’s disposal and others use that asset to underscore pricing and value messages. Many use downtime to create other value for their customers. Maintenance services, for example, will fill troughs in demand with routine or preventative maintenance.

As the service is produced while the buyer uses it, the customer is effectively “in the factory”, able to see the production process and unable to see the finished result. So the production process must be well prepared and tested, able to host customers and engage them professionally without causing anxiety. Simultaneous consumption also contributes to the need for marketers to manage expectations. They must explain the key steps in the service process and any tasks that the customer must undertake. In fact, one mistake made by many is their failure to sufficiently plan or design the process through which their customers will move (see blueprinting).

Simultaneous consumption has implications for quality management because recovery must happen in real time. Quality processes cannot be the same as manufacturers’ post production sampling and correction because any error will be immediately experienced by the customer. Any marketing messages will be undermined if the actual experience is poor or the firm is slow to remedy service errors. So simultaneous consumption concentrates marketers’ thoughts on ensuring a quality experience; it reinforces the need to understand and exploit quality of service issues in their work.

(iv) Inseparability

Credible academic researchers (see, for instance, Zeithaml and Bitner, 2003 and Berry, L.L., 1995) suggest that, in the customers’ mind, most services cannot be separated from the person they encounter when they buy and use them. So people are not only important to the design and management of a service, they are a critical part of the service itself. Their motivation, behaviour, and appearance are part of the benefit package offered to customers. In many ways they are an essential element in the value that customers seek, part of the bought service, and their behaviour affects the customers’ perceptions of price and quality. They are so intimately involved in delivering the service experience that their body language and appearance will communicate messages to the customers about the service as much as their words or the firm’s marketing claims.

So, at the front line of interaction with customers, a firm’s employees must embody its intentions and, as a result, the appropriate treatment of employees is very important to service businesses. If employees of a production company are treated as mechanized “units of production” their boredom or dissatisfaction will not be passed on to the buyers. But in a service business it will. If their leaders treat them badly then it will be communicated, even if they try to be professional and disguise their unease. Conversely, if they are treated like human beings there is a strong chance that the customers will be too.

Managing employee behaviour in line with changing customer expectations is a major focus and challenge for service businesses. Good service managers understand that front line people can cause customers to turn to or away from a service. Many put real effort, investment. and resources into programmes designed to improve the impressions caused by their people. In fact, it is probably no exaggeration to say that service companies invest in this “intangible asset” the way manufacturers invest in tangible assets.

On the other hand, an increasing number of services are based on self-service technology, with no people involved in day-to-day delivery. From web services to airline check-in, the range of self-administered services is steadily growing. Clearly, in this rapidly increasing category of services, the “people” element of the service marketing mix is less prevalent. For these, the personality of the company brand is used to replace the people who normally deliver service. Marketers must invest heavily in branding this type of service at all points of visibility. The emotional reassurance of major, high quality brands like IBM, Ericsson, or Virgin implies a reliable response should self-service technology fail.

However, there is evidence that self-service technology only penetrates a market if the first buyers are shown how to use it by personable people or their proxy. They need help with the initial socialization process, and in overcoming any technology fear, from specifically designed marketing initiatives. At the time of writing, for instance, most airlines are introducing self-service check-in technology that is very simple to use. They generally place the machines near the “hand luggage only” queue. Employees are trained to approach people in the queue, often frequent flyers, and show them how to use the fast, easy machines. Although many refuse the original offer to use the technology, they are happy to comply once a demonstration overcomes their technology fear and potential embarrassment. Once a sufficient number of people have leant the process, they communicate it to others and the self-service technology penetrates the market.

(v) Perishability

Generally services cannot be stored or saved for other occasions. Once an empty airline seat has flown over the Atlantic, the opportunity is passed; the moment cannot be recaptured. So, services are time bound and the management of time is an important task of a service business. In fact, one researcher (see Ruskin Brown, I., 2005) suggests that there are several “flavours of time” that service businesses need to manage: punctuality, duration, availability, speed of response, and speed of innovation. Of these, punctuality or reliability, in the sense of delivering the service when promised, has been shown in many studies to be one of the most important influences on the way customers judge the quality of a service.

Perishable services must be marketed in the same way as perishable products like fresh food or flowers. Quality difficulties must be dealt with through an immediate, responsive recovery process and inventory must be carefully managed through forecasting and capacity management. This characteristic reinforces the need for good demand forecasting in a service business. It probably has to be more accurate than a product company that can store excess items in a factory until they are used. Maximum capacity must be carefully calculated, balancing the highest anticipated demand against the cost of investment. Marketers have to cope with variations in demand and develop techniques to sell spare capacity such as empty hotel rooms for off-season or weekend capacity. Emphasis should also be put on easy and efficient distribution and the benefit of a new, premium service.

However, the real implication of this is that the supplier must become expert in differential pricing. They need clear communication methods to potential buyers, which demonstrate why the immediate “fresh” service needs to cost a different amount to those accessing it at a later time. They need to produce special price offers, reductions to use up spare capacity, and understand marginal pricing. Moreover, they need to communicate the rationale and, particularly, the fairness of these pricing practices to their customers. This is particularly important for companies with repeat customers who become increasingly sophisticated, holding off purchase to get better offers.

(vi) Ownership

When people buy a product, ownership of it passes to them. They can store it, use it, or give it away. This simply doesn’t happen with a service though. The people who are part of a training or consultancy service cannot be owned by the buyer. Nor are airline or train seats bought; they are rented for a moment in time as part of the service. Payment is for use, access, or hire of items. People will talk as if there is a sense of ownership (my flight, my broadband service, my pension or our training) yet there is not the same sense of possession as with a product purchase. This lack of ownership will cause buyers to question value and price. They will look for greater added value or ask for price reductions. As a result, the marketer must dramatize the moment of contract and find mechanisms to emphasize value as the service progresses or they will struggle continually with price pressure. This is one area which many firms find hard to manage. In a variety of businesses, numerous valuable services have been turned into commodities because the suppliers have been incompetent at communicating value.

(vii) Process

One of the major differences between the purchase of a product and the experience of a service is the process through which the buyer moves. A product is an entity, which is bought through a process but is independent of it. Customers can use it, break it, give it away, and ignore the instructions on how to use it. Services, however, have a process inherent in their design through which the customer must pass. So when people use a service they must submit themselves to the service provider’s process.

So, marketers must plan the service process in detail and educate their customers in the parts of the service they will experience. Potential customers must know how to access the supplier’s service system, which has to be designed to encourage use. The firm needs to use clear signage and communicate its meaning to all potential buyers. Educating them to access and use the supplier’s process is, therefore, an important aspect of service marketing. This ranges from the deployment of branded consumer signage, like McDonald’s, to the use of customized web sites for client extranets in business-to-business marketing. Once “in the premises”, though, the customer needs direction (even in a virtual environment). If it is not immediately apparent how to use the system (the equivalent of standing helplessly in a foreign shop) they become embarrassed and give up. So, clear signage into the delivery process and a step-by-step guide through it are equally important. On landing, for example, many flights show a video guide through the airport. This ensures that the stress levels of new passengers stay low and any difficulties are seen as aberrations, which can be corrected by excellent service recovery. Finally, marketing communication must concentrate on the “outcomes” of the process rather than the product benefits emphasized by product marketers.

(viii) Control

When a customer buys a product, they normally have complete control as to when and how to use it. They might keep it, use it immediately, or give it to someone else. When they buy services, though, they do not have such freedom. They must surrender themselves to the service delivery process, which the supplier has designed for them. In doing this they cede control of themselves to the service provider and human beings detest being out of control. The purchase and use of a service therefore invades their personal space and raises emotional issues that service suppliers must learn to tackle (see Bateson and Hoffman, 1999 and Bateson, 1985).

This lack of control means that marketers must take steps to allay the anxiety of new users. They can, for example, design a simple, clear process and choose competent employees to perform the service. Both will help to alleviate anxiety. Many of the well known customer service and after care techniques (see service quality) may be used to allay fears and criticisms arising from this underlying emotion. Yet, although the character, reputation, and professionalism of service employees can inspire confidence in the quality of the service to be received, the corporate brand also allays stress.

Unfortunately, customers who use a service repeatedly assert an unconscious need to regain control. They try to cut corners, look to serve themselves, and get irritated if the process is inflexible. In fact they can become annoyed with the simple, clear steps that they first found so enticing and necessary. So, service for the experienced user is very different to that for the new customer. It must be inclusive and respectful; a streamlined club, similar to frequent flyer programmes, which allows as much self-service as possible. This has profound implications. In fact, in some markets, the arrival of a supplier offering, for the first time, a service designed for the experienced user has had major strategic impact.

For experienced buyers, marketers must ensure that mechanisms are designed whereby, as the customer becomes familiar with the service process, he or she can do more themselves or cut out steps. The design of progressive self-service into the service system will reduce costs because some of the effort of performing the service will come from the customer. Yet, it will also improve perceived quality because the service performance is within the control of the customer and thus closer to perceptions of timely delivery. So, it is possible for marketers to provide repeat customers with better service at lower cost.

(ix) Environment

For many services the environment in which they are performed is an important part of the experience for customers. The design and ambience of a restaurant and the layout and style of an airline cabin set expectations of quality and value. Retailers, hoteliers, and managers of holiday resorts are just a few of the service businesses who have to think carefully about the physical setting of their service. It affects the behaviour of employees, sets the expectations of buyers and can be a source of differentiation.

There is a wealth of research on the effect of the physical setting on the health of a service business. A complex and sophisticated process is involved in creating a new one because the marketer must take into account and balance a range of factors including: “sight appeal”, “size perception”, shape, colour, sound, scent, spatial layout, flexibility, brand, and signs or symbols. They must also calculate operational factors such as capacity, crowding, and queuing. In fact, some businesses use complex statistical techniques like queuing theory (that are used to design the capacity of sophisticated communications and computer equipment) on the flow of people through their premises. Yet in international or ethnic markets, they also have to allow for subtle cultural preferences which influence a range of ambient and behavioural factors.

For those services where the physical setting is important, these complex considerations are unavoidable because they affect buying behaviour. Credible experiments have demonstrated the effect of these different factors on sales. People buy more, for instance, if different music is played, if different colours are used, and even if different smells are deployed.

Some services, though, are experienced in more subtle and flexible environments: the virtual vagaries of the internet or the customers’ imaginations. Yet, just as in a real, physical environment, impressions need to be created which set expectations of value. This needs careful design and sophisticated marketing if it is going to influence sales and price perceptions.

After initial design and launch, the “service-scape”, the environment visible to customers, must be kept fresh and inviting by marketers. It must continue to reflect the ambitions of the service provider. Marketers must design sales promotion campaigns and point-of-sale materials to stimulate sales, to increase the margin of purchases and to maintain excitement in the service. They must routinely audit the facility, ensuring that it maintains its enticing nature to customers.

(x) Performance

Services tend to occur at a moment in time and involve the attention of one person on another. Many are “performed”, not produced. From representation in negotiation, to service at the restaurant table, people perform a service for others and the style of performance affects the customers’ views of both quality and value. Moreover, the energy, art, and style of the performance influence the price that can be charged and the degree of customer satisfaction. As a result, the service industry puts great emphasis on the “service encounter”; that “moment of truth” when the supplier’s employees interact with the buyers. It is a moment when the firm has a chance to impress and deepen a relationship with a buyer, in addition to delivering the promised benefit. It is this area, probably, more than any of the others, that creates exhilarating, enticing services. A service can be researched, blueprinted, and engineered but those which go the extra step of creating a performance tend to entrance their customers and earn higher margins.

History, Context, Criticism, and Development

Early experience of service marketing and understanding of it in marketing text books (one 1920s text examines the “intangible product”, see White, P., 1927) seemed to get lost in a fascination for consumer product marketing in the mid 20th century. As a result, until recently, the majority of marketing theory, language, and practice derived from either the experience of firms offering physical goods (particularly consumer products) or from economic theory. Consequently, many marketing techniques are modelled on product experience (particularly in consumer markets) and most marketing teachers at leading institutes had their early career in a product environment. It is in the past three decades, as Western economies have become more service dominated, that marketers have begun to move from traditional product disciplines to service environments in any significant numbers. So, coupled with the emergence of competitive service sectors in the developed economies, there has been a growing interest of marketers in this field. They are adapting marketing practice to a wider range of service businesses (whether in business-to-business or consumer, profit, or non-profit industries) and to an increasing number of activities within different service businesses.

Until the 1970s there were few well researched and objective analyses of either the role of marketing in service industries or service marketing practice. This was changed by two groundbreaking pieces of work. The first was a paper produced by G. Lynn Shostack (see Shostack, G.L., 1977) when she was a vice president of Citibank in New York and marketing director for the Investment Management Group of America. It was a set of detailed recommendations based on the experience of a senior manager working in a service industry. Shostack clearly used the processes and procedures outlined in her article to design new services and had some success with them. She suggested a number of ideas which have formed the basis of much service marketing thinking ever since. Figure S.3, for example, is her illustration of the range of offers beyond mere physical products. Her primary idea was that there are features of a service which make its creation and marketing different from the creation and marketing of products. In particular Shostack talked about the concept of “intangibility”. She suggested that the intangibility of a service is a state which makes the offer fundamentally different from a product offer; “it is not corporeal”. This has since become part of the fundamental philosophy of service marketing.

The next significant contribution appears to be a 1983 symposium of the American Marketing Association which debated in detail the marketing of services. The full agenda covered the creation of new services, the management of innovation, and the differences between the marketing of services and products. The meeting was clearly held as a result of growing interest in service marketing stimulated by the Shostack article and a concern that the marketing community was not addressing some of the key issues involved in the move to a service economy. The symposium stimulated various academics to contribute to this field. In particular, there appeared publications by Leonard Berry, Sri Parasuraman, Christian Grönroos, Christopher Lovelock, Donald Cowell, Roland Rust, Stephen Brown, and Valerie Zeithaml. These people in turn sponsored many research projects into service phenomena and set up high quality institutes with industry.

It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that there are now three academic “schools” following this field: the American school, the Scandinavian school, and the French school. Each has a different emphasis but all cooperate in a wide body of research, much of which is conducted in tandem with people in actual service businesses in a variety of countries and economic sectors. There is, then, science behind the marketing of services. Marketers wanting to adopt many of the approaches can generally rely on the applicability and relevance of much that is suggested.

In recent decades larger companies in service sectors have begun to establish substantial marketing departments similar to those in consumer goods industries. Banks, utilities, travel firms, and retailers have learnt to use these structures to market services as their industries have experienced greater competition or, as in the case of newly privatized utilities, market forces for the first time. Some of these firms appear to be adopting the processes of marketing seen in consumer goods companies, and embarking on decades-long organizational learning in marketing effectiveness. BT, for example, had no marketing resource at all when, in 1984, it was a government-owned engineering organization. It now has several hundred marketers working on brand, communication, and strategy programmes; and has a number of highly successful, award-winning campaigns to its name. More importantly, though, it has sophisticated campaign management processes which are progressively improved alongside other operational capabilities. In parallel with all this, though, the marketing profession as a whole has been exploring how different the marketing of services is from the marketing of consumer products.

Voices and Further Reading

- “… I have worked in service companies (McKinsey and American Express) and product companies (RJR Nabisco and IBM). I will state unequivocally that service businesses are much more difficult to manage. In services you don’t make a product and then sell it. You sell capability. You sell knowledge. You create it at the same time you deliver it. The business is different. The economics are entirely different.” (Gerstner, L.V., 2002).

- Thomas, D.R.E., “Strategy is different in service businesses”. Harvard Business Review, July–August 1978.

- “To the buyer, then, services … are necessary to enable him to develop the full economic value of the goods, and he is generally aware of this. Most buyers of industrial goods recognize that part of the price they pay represents the value of accompanying services, even where those services are not paid for as an individual item.” Rose, D., in Wilson, A., 1965.

- Lovelock, C.H., Service Marketing. Prentice Hall, 1991.

- “The concept of ‘service’ evokes, from the opaque recesses of the mind, time worn images of personal ministration and attendance. It refers generally to deeds one individual performs personally for another. It carries historical connotations of charity, gallantry, and selflessness, or of obedience, subordination and subjugation.” Levitt, T., 1972.

- “It is wrong to imply that services are just like products except for intangibility. By such logic, apples are just like oranges except for their ‘appleness’. Intangibility is not a modifier; it is a state. Intangibles may come with tangible wrappings but no amount of money can buy physical ownership of … experience … time … or process. Tangible means palpable and material. Intangible is … impalpable and not corporeal. This distinction has profound implications.” Shostack, G.L., 1977.

- Levitt, T., “Marketing intangible products and product intangibles”. Harvard Business Review, May–June 1981.

- Cowell, D.W., The Marketing of Services. Butterworth-Heinemann, 1984.

- “Goods are produced, sold and consumed whereas services are sold and then produced and consumed.” Cowell, ibid.

- Grönroos, C., “Applied service marketing theory”. European Journal of Marketing, 1982.

- “Services are processes consisting of activities or a series of activities rather than things. In order to understand service management and the marketing of services it is critical that one realises that the consumption of a service is process consumption rather than outcome consumption. The consumer perceives the service process (or production process) as part of the service consumption, not simply the outcome of that process, as in traditional marketing of physical goods … the consumption process leads to an outcome for the customer, which is the result of the service process. Thus, the consumption of the service process is a critical part of the service experience.” Grönroos, C., 2003.

- Palmer, A., Principles of Services Marketing. McGraw-Hill, 1994

- Payne, A., The Essence of Services Marketing. Prentice Hall, 1993.

- Bateson, J.E.G., Managing Services Marketing (text and readings). Dryden Press 1989.

- Woodruffe, H., Services Marketing. Pitman, 1995.

- Irons, K., Managing Service Companies. The Economist Intelligence Unit, 1993.

- Ziethaml, V. and Bitner, M. J., Services Marketing. McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Service Marketing: Victorian Jim Reforms the Midland

It is very hard for modern people to really understand (especially any that have been stuck on an Amtrak train during a snow storm) just how revolutionary, scientific, and advanced the railways were when they first appeared. This was the first time in human history that mankind could travel faster than a galloping horse, and it is no exaggeration to say that the railway transformed society.

The first real railway line went operational in Britain (Darlington to Stockton) in 1825 and proved to be a fabulous investment for its Quaker owners (returns of 15% between1839–41). It prompted a railway mania and investment boom. By 1840, 200,000 people were involved in railway construction in the UK alone. British Iron output doubled as a result of it and, by 1850, £240 million had been invested. By 1869, the first transcontinental railway had been completed in the USA and, in 1891 the construction of the massive trans-Siberian railway had begun in Russia.

The railways created new towns, new concepts, and new jobs. In London, for instance, a young insolvency specialist called William Deloitte created a new system of accounting for these industrialized service businesses and, through such advanced thinking, created the major accounting firm that still bears his name today. The railways introduced consistent time, holidays, commuting, and new concepts like the word “class”. Historian Eric Hobsbawm says of them (Hobsbawm, E., 1999):

By 1850 the railways had reached a standard of performance not seriously improved upon until the abandonment of steam in the mid twentieth century, their organization and methods were on a scale unparalleled in any other industry, their use of novel and science-based technology (such as the electric telegraph) unprecedented. They appeared to be several generations ahead of the rest of the economy, and indeed ‘railway’ became a sort of synonym for ultra-modernity in the 1840’s, as ‘atomic’ was to be after the second world war. Their sheer size and scale staggered the imagination and dwarfed the most gigantic public works of the past.

Despite the work of novelists like Thomas Hardy and Charles Dickens, it is also hard for modern audiences to understand the attitude of educated and wealthy people to the poor during that period. Many resisted, for example, any education initiatives because they feared that it would cause unrest. There were, though, a number enlightened souls pushing for reform. Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, caused outrage and concern, for instance, when he insisted on there being days when the poor and uneducated could visit his “Great Exhibition”. Another reformer was James Allport, who ran Britain’s Midland railway in the mid century.

His first significant act caused as much outrage and concern as Albert’s. At the time, “third class” was for the poor and working people. It normally consisted of simple open carriages with wooden benches, which were given low priority. There are reported instances of third class trains being shunted into sidings to let even cattle or freight pass them by. Allport abolished this. He had covered carriages, all of which had upholstered seats, partitioning, and more leg room. His peers in the industry hated him for it because (as BA did with flat beds in business class a century later) he set a new standard for the basic service offered on this new and exciting network of technology; and they had to keep up. For him, it was not enough just to offer carriage any more. He wanted to serve people.

He contracted with a successful catering company, Spiers & Pond, to ensure that wealthier travellers could enjoy a food service. They had begun their business with sporting events like Wimbledon and opened the Criterion restaurant which still operates in London’s Piccadilly. Passengers could buy one of their hampers at one station and drop it at another after eating the contents on the train. Their service became a social occasion, famous in Victorian England. In his extensive history of advertising (Sampson, H., 1875), Victorian author Henry Samson could have been describing the answer to airplane food:

Ten years ago no man in his senses would have dreamt of applying for food or drink at a railway buffet while he could go elsewhere; now Spiers & Pond daily serve thousands who desert the old familiar taverns and crowd the bars at the various city stations. … the old regime of mouldy pork-pies and stale Banbury cakes has made us feel very well disposed to a firm whose name has already passed into a proverb.

The following personal advert from the Daily Telegraph of 1874 shows how much this service had become part of social life:

The lady, who travelled from Bedford to London by Midland train on the night of the 4th inst, can now meet the gentleman who shared with her the contents of his railway luncheon basket. She enjoys the recollection of that pleasant meal, and would like to know if he is going on another journey. Will keep any appointment made at the Criterion in Piccadilly.

Allport’s other remarkable innovation was to create a premium service on his railway. He constructed an outsourcing contract (yes, an outsourcing contract in the 1870s!) with America’s famous Pullman trains. They provided a “hotel standard service” for an extra fee, using their own carriages and attendants. In fact, Allport had been so effective at increasing the return on the basic rail service that he was eventually asked to run another innovation, the railway clearing house, which handled ticketing and pricing across the whole national network. He repositioned the value of the core service based on a novel network infrastructure and created attractive added value services. An outstanding services marketer.

![]() RATING: Practical and powerful

RATING: Practical and powerful