![]() INNOVATION MANAGEMENT

INNOVATION MANAGEMENT

Application: New Revenues, New Products and Services, New Strategies

The Concept

Innovation is a management process, the mechanism by which an organization captures, cultivates, and exploits initiatives. It is different from creativity itself which is the source of initial insight or ideas on which innovative new offers are founded. Traditionally, people have thought that there is a need to innovate in offerings, process, and market. There are, though, well researched projects and many anecdotal stories about the need to bring innovation to many aspects of businesses. They suggest that innovation in functions like strategy, governance, management, NPD/NSD, operations, marketing, and sales is vital in fast changing markets; that sclerosis can destroy value.

Creativity and innovation are particularly vital to a firm that needs to bring a range of new products and services to market. In fact, some researchers suggest that the ability to innovate new products and services is the key to survival for some companies operating in a number of mature or fast changing markets. In the 2010 results of McKinsey’s annual innovation survey of senior executives, for instance, 84% said that innovation was either very or extremely important to the growth of their companies (McKinsey Quarterly, July 2010).

In recent years a number of businesses have adopted successful methods of harvesting creative insight, in addition to ensuring that creativity is stimulated in the first place. They vary enormously but can be grouped into several generic approaches.

(i) Innovation Founded on a Formal Process

The proactive creation of new products (NPD) has been established practice for many years in a number of different businesses selling physical products. Leading organizations in markets where new product innovation is a critical success factor, like consumer products, have highly sophisticated processes, which are managed at a senior level in the firm. See NPD/NSD.

(ii) Innovation Through Smallness

Others, by contrast, emphasize smallness as a means to innovation. For instance, in a recent speech, Sir Richard Branson attributed part of the success of his Virgin organization to smallness. His policy, he said, was to break units in two once they had reached “around thirty” people. He had found that it maintained entrepreneurial spirit and kept overheads low. This approach is founded on a story which has become the stuff of business legend. In the 1960s, the American multi-national 3M nearly missed a major opportunity. Its Dr Spencer Silver had produced, a “low-tack reusable adhesive” (glue which didn’t stick well). He saw the potential to create what became “Post It” notes. Unfortunately, the concept was rejected by all (including the marketing department). However, he did not give up on the idea but began to manufacture samples, which he gave to the board’s secretaries. As they asked for more, word spread and demand grew until the amateurish manufacturing capability for the notes took over his supportive boss’s office. The company eventually accepted the innovation, which became one of its most successful products. Then, as a response to the fear that its large, bureaucratic structure might miss a significant product opportunity because of its short-sightedness, it broke down into small cells. It claimed that this was responsible for a number of subsequent innovations.

The approach can be seen in several different industries. In the technology industry, for instance, not only have some large companies sought to create entrepreneurial growth through small business units, but the character of places like Silicon Valley have facilitated interaction between capital investors and numerous start-ups. Leading creative technologists have grown used to the fact that tiny start-ups can grow into massive, valuable businesses like Google. Innovation through smallness has also been the reason for the success of many of the professions. Even in the largest firms, success lies in their individual practices, which, like cells in a living organism, evolve and respond to changes because they are run directly by a partner. As an owner of the business they feel freer than corporate executives to take their own course and refine their own offer. In fact, some leading practices ask partners to write and then implement a “business plan” which sets the direction for their practice; especially if in a completely new field of operation. There is even evidence of partners developing a practice in defiance of the wishes and policies of leaders, sometimes to great effect. So, fostering an innovation by dedicating a practice to it is common in the professions. Typically, though, this is intuitive and not part of structured “innovation management” policies or any managed process. Experience suggests that marketers can improve the success of this approach if they make explicit a mechanism to identify, nurture, and prioritize developing ideas.

(iii) Outsourcing Innovation Management

There is a view that creativity occurs less in large, bureaucratic, and process-dominated organizations and that innovation management rarely manages to exploit it. So, 47% of the executives who responded to McKinsey’s (see McKinsey, 2010) innovation survey said that they sourced innovation externally. This is probably in response to a concept called “open innovation”, described by US professor Henry Chesbrough. It was famously prompted at Proctor & Gamble in 1999 when, in response to analysts’ pressure, an incoming CEO (Alan Lafly) challenged the organization to source innovation from outside (as opposed to just from its own, extensive R&D facility).

Some product companies have, for example, managed creativity by using an external agency; innovation through outsourcing. These agencies, which came to prominence in the 1970s, are known as “new product development companies”. They take a brief in the same way that advertising agencies or research companies take briefs from marketing departments. These briefs contain requirements to produce new products, offering benefits to new markets for whatever reason. The famous cream and whisky drink, Bailey’s Irish Cream was, for instance, created in this way. The then owners of the drink commissioned it from a creative agency because they had spare manufacturing capability in their Irish plant. The original brief, it seems, contained a requirement to produce an alcoholic drink product which contained “typically Irish components”. These suppliers have specialist processes to explore the target market, to design the offer, and to specify manufacturing and packaging. They return to the company a researched concept which can be taken, through a detailed business plan, into manufacture.

(iv) Exploiting the “diffusion of Innovation”

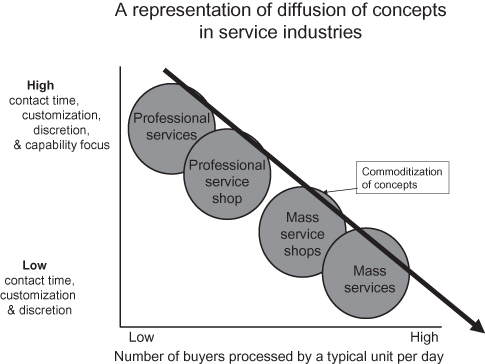

As described in the separate entry, the acceptance and growth of an innovation in society occurs through dialogue amongst a network of inter-related people. Its diffusion depends on relationships and conversation. Marketers can use this phenomenon to develop new services and marketing concepts. There is, for example, a specific type of innovation diffusion which occurs in the professional services industry, represented in Figure I.1. Consultancies which specialize in high-end customized services, like McKinsey, usually undertake complex projects to solve unique client problems. However, if their practice meets a problem several times, the type of engagement will be given a name and a new concept is born in the industry. Other suppliers will then take up the offer, creating processes and tools to handle it. It moves down the “industrialization” line, picking up volume but losing margin. Eventually the approach becomes commonplace, is captured in software tools, is taught in professional academies, and undertaken by customers themselves. It becomes more of a commodity. Offers like double entry book keeping, portfolio planning, and process reengineering have followed this course; and it is seen throughout the industry today. Yet, different offers suit different firms at different stages in the commoditization journey. High-end strategy firms pioneer new concepts, whereas one of the IT-based management consultancies, such as Accenture, might be better suited to volume, process-based offers. Marketers can identify potential innovations for their practice if they have a clear view of the concepts that are appropriate to its competences and by adapting ideas from others as they diffuse across the professions.

Figure I.1 A representation of the commoditization and diffusion of concepts in the services industry

(adapted from Johnston, R. and Clark, G., 2001)

In his definitive study on the use of this concept in technology companies, Geoffrey Moore (Moore, G.A., 1991) pointed out the difficulties that companies have in bringing true innovations to market. He emphasizes the need to take different approaches in marketing strategy and technique as diffusion progresses. The differences in the pace of development of high-tech services like Broadband over optical fibre (originally proposed in the 1980s) and either the internet or iPhone apps shows that this level of sophistication in innovation marketing is just as relevant in services marketing.

(v) Innovation Through thought Leadership

As discussed in the separate entry, thought leadership is one of the most influential marketing strategies that the world has seen. It is a vast, influential, and diverse range of activities, which, at its best, produces systematic, iconic work like the McKinsey Quarterly and the Harvard Business Review. It is both a source of innovative new services and a marketing tool that helps sales. Leading consultants like Accenture, IBM Global Services, and Deloitte have skilled staff dedicated to this function. What starts with an idea and a marketing campaign can soon have consultants and leading practitioners dedicated to it. It becomes a “practice” in its own right, sometimes earning millions of dollars in revenues. Leading businesses have, for example, had practices focused on “CRM”, “Lean service”, and “shareholder value”; each innovative ideas in their own time.

(vi) Innovation Through Imitation and Adaptation

Another valid form of innovation is the adaptation of emerging ideas; when, for instance, a supplier adopts and adapts a new idea, product, or service, which has been created and pioneered by a peer in their industry. As new concepts occur, they are often pioneered by small, flexible businesses or by notable individuals. However, it tends to be when organizations with a huge footprint take them on board, that they have substantial impact and a new market is formed. So it is a natural evolution and a source of real profit to identify emerging ideas and adapt them. Some would argue that this is not true innovation because the results not completely new. Yet, famous strategy professor, Ted Levitt, argued as far back as 1966 (Levitt, T., 1966) that this was a valid form of innovation, which was less risky than blindly pursuing the entirely new idea or offer. Innovation is not only about completely new ideas but also about the sensible adaptation and improvement of concepts pioneered by others. IBM originally moved into computers (and later the PC) through imitation; as did Virgin in air travel (after Freddie Laker) and Ericsson in mobile phones. This is not to argue that the services or products that result are not unique or appealing. These companies adapt a concept without infringing copyright or patents; making it their own and producing a unique new value proposition.

(vii) Innovation Through Co-Creation

Creativity tends to occur in all businesses as they interact with customers. As local people (particularly in large, diffuse businesses) respond to needs, solve developing problems, and tackle the unintended consequences of central policy, they frequently find creative new answers to needs. This is particularly common in service companies because of the involvement of human beings in the interaction between the two sides. Unfortunately, these creative answers to local problems are, like fast blooming wild flowers, frequently lost. So some companies put great stress on capturing local innovation across the operations of their company and communicating it across the whole firm. Some marketing VPs, for instance, see part of their role as identifying and legitimizing innovation that occurs in the field. They stress the need to set up mechanisms capable of industrializing it and replicating it across their company. In many cases, this leads them to concentrate on mechanisms by which they can create innovative ideas with customers.

The “co-creation of services”, for example, is the practice of developing new services through collaboration between companies and customers. Innovation and value is created by the firm and the customer, rather than being created entirely inside the business. Co-creation not only describes a trend of jointly creating offers but also a movement away from customers buying products and services as transactions. It leads to purchases being made as part of an experience.

It is common for firms to take ideas from their customers and develop the way in which they deliver their products to them. They try to get customer input into the way they enjoy the offer; in fact some create online communities, exploring and understanding how customers use the offer and then seek their ideas on how to improve delivery. This is a way of improving the customer’s experience without affecting the product itself. It is also a way to bring the customer inside the business, helping them work with the brand on a part of the experience that matters to them most. Co-creating products and services, however, goes beyond this, it might, like Amazon, allow customers to select and change their delivery times. Many airlines, for instance, allow real-time self-service for their customers, letting them choose and change their seat, meal, and even their flight time. In some business-to-business cases, customers work with suppliers on a deeper level of engagement to create entirely new offers. The suppliers then bring these into their portfolio and offer them across their business.

(viii) Innovation Through Rivalry

There is an assumption made in much modern business literature that organizations should be efficient, smooth, and harmonious. But life isn’t like that. Business organizations are structured in different ways and contain ambitious, driven people who thrive on competitive thrust. In fact, some organizations (law firms for example) are configured to grow by exploiting and nurturing this ambition. There is evidence that this rivalry produces innovation (see Ferrari, B.T. and Goethals, J., 2010).

One credible study amongst British market leaders (Davies, R., 2010) focused on barriers to innovation. They found them to be:

- Lack of knowledge.

- Skill-related barriers

- Lack of trust

- Lack of space (i.e. energy from leadership amongst other priorities)

- Cultural alignment

- Structural barriers.

Marketing leaders need to understand these inhibitions on change in their organization if they are to develop new offers or new approaches to market. The research indicates that in many corporate companies, change management might be an important component in the innovation programme of marketing functions.

History, Context, Criticism, and Development

Innovation of products, services, and strategies has undoubtedly been a part of marketing and business life for many centuries. It is, of course, closely related to innovation in science and technology. As breakthroughs occur in technical fields it allows entrepreneurs to take advantage of business opportunities and create new markets. So, it is clearly related to diffusion of innovation of new scientific developments. In fact, since the mid 20th century in particular, governments have created policy and initiatives to encourage cooperation between universities and business entrepreneurs or financial investors. In fact, there is evidence that, in some places, marketing skills can be left out of the thinking of science specialists working to bring innovation to market.

Since the 1960s there has been a recurring belief in many circles that companies have to keep innovating new products and services to survive. Many assert that this is essential to thrive in fast changing and commoditizing markets. This is slightly dubious though. If the studies (from the 1960s and 1970s) showing that a vast percentage of revenues resulted from new products were, in fact, credible, then the companies and sectors involved would have churned their complete portfolios many times by now. Yet, as Tables B1 and B2 show, there are many branded items in all sectors that have survived and thrived for several centuries. It seems, then, that this drive for innovation needs a degree of realistic perspective and balance.

At the start of the 21st century, there was a resurgence of focus on innovation. This was influenced largely by IBM’s massive thought leadership campaign on the subject. In 2006, they launched a massive international campaign (which included TV, print, outdoor, and web) “Innovation That Matters”. It was their primary campaign for the year, and would have involved spend of several million dollars. The aim was to reposition IBM as supplying the means for corporations to innovate – structurally, financially, or operationally. There is little doubt that it kick-started a renewed interest in innovation. Consultancies developed “white papers” and several creative agencies re-badged themselves as innovation companies.

Voices and Further Reading

- “We live in a business world that increasingly worships the great tribal god: innovation; lyrically hailing it not just as a desired but necessary condition of a company’s survival and growth. This highly agitated confidence in the liberating efficacy of innovation has in some places become an article of faith almost as strong as Natchez Indians’ consuming faith in the deity of the sun. Man creates gods according to his needs. Significantly, the businessman’s new demigod and the Natchez’s more venerable and historic god make identical promises. They both promise renewal and life. Yet before all our R&D energies and imaginations are too one-sidedly directed at the creation of innovations, it is useful to look at the facts of commercial life. Is innovation all that promising? More important, how does a policy of innovation compare in promise to more modest aspirations? What is needed is a sensibly balanced view of the world. Innovation is here to stay, it is necessary, and it can make a lot of sense; but it does not exhaust the whole of reality. Every company needs to recognize the impossibility of sustaining innovative leadership in its industry and the danger of an unbalanced dedication to being the industry’s innovator. No single company, regardless of its determination, energy, imagination, or resources, is big enough or solvent enough to do all the productive first things that will ever occur in its industry and to always beat its competitors to all the innovations emanating from the industry.” Levitt, T., 1966.

- “Innovation and commercialization, 2010: McKinsey global survey results”. McKinsey Quarterly, July 2010.

- “… innovation processes in large companies stifle exactly those radical developments which the firms seek”. Ambler, T., 2003.

- Hamel, G. and Prahalad, C.K., “Corporate imagination and expeditionary marketing”. Harvard Business Review, July–August 1991.

- Brown, R., “Managing the ‘S’ curves of innovation”. Journal of Marketing Management, July 1991.

- Trott, P., Innovation Management and New Product Development. Prentice Hall, 2008.

- “Traditional arguments about innovation have centred on two schools of thought. On one hand, the social deterministic school argued that innovations were the result of a combination of external social factors and influences, such as demographic changes, economic influences and cultural changes. … On the other hand, the individualistic school argued that innovations were the result of unique, individual talents and such innovators are born … The resource-based view of innovation focuses on the firm and its resources, capabilities and skills. It argues that when firms have resources that are valuable, rare and not easily copied they can achieve a sustainable competitive advantage – frequently in the form of innovative new products …” Trott, ibid.

Things You Might Like to Consider

(i) The innovation of new products, services, and strategies is undoubtedly a marketing responsibility. Experience suggests that it is not confined to the NPD/NSD processes that are so loved by academics. Marketers needs to find the appropriate style of innovation for their organization.

(ii) It seems important to keep a sensible, judicious perspective on this. Apple, the iconic case study for all advocates of innovation, had a very difficult and vulnerable history until its massive breakthroughs with the iPhone. Not all firms can innovate in this way.

(iii) There are alternative strategies. The nurturing or refreshing of a long-standing brand franchise might also be viable.

(iv) Communication strategies need to match innovation initiatives. If it is a truly novel concept, then all those strategies to promote at that point in the diffusion of innovation should be adopted. If it is, say, an innovation in a well established and understood category, then different marketing communications strategies apply.

Allen & Overy grows further

Allen & Overy is one of the world’s leading law firms with around 450 partners and nearly 3,000 lawyers working in over thirty-three cities around the globe. It is one of a small group of truly integrated international law firms and one of the UK’s “magic circle”.

The partnership has grown by offering high end, customized professional services. It is seen as one of the elite practices in its field, built on its partners’ reputations for individual excellence. The firm obviously offers a wide range of legal services, from M&A instructions with leading financial institutions through corporate law to specialities like estates and insolvency. It has sector skills in fields like communications, media, and technology; energy and utilities; financial institutions; hotels and leisure; infrastructure; licensing and gaming; and life sciences. It has partners with expertise in all these fields and has created thought leadership on subjects in many of them.

The core of its client base comprises several thousand significant organizations in a variety of sectors and locations. In fact, it is on the “legal panel” of many of the world’s most well-known and influential organizations. Globalization is leading the partnership to concentrate on a core group of clients, common to many of the offices in their network. In this arena they compete with a small number of global and US-origin law firms in addition to leading local law firms. So the firm has well established strategies to concentrate on important clients, to appoint client relationship partners, and to give a more sector-specific orientation to its advice.

The partnership thinks that the international legal services market is changing due to a number of forces; including:

The 2009/10 financial crisis which gave impetus to the drive among clients to reduce legal spend and focus on the efficiency and value delivery of their external law firms

The commoditization of a number of services, leading to new forms of delivery like international outsourcing or technology-based services.

The introduction of professional buying skills into the purchase of legal services.

As a result of these forces, the firm has begun to experience two opposing but related forces.

The first is a tendency toward cost cutting, automation, outsourcing, and process efficiency. Within its field of operations, it has been asked to provide more streamlined, efficient, and competitively priced services. In areas such as syndicated loans to investment grade credits or leveraged loans in private equity, there is a tendency toward standard forms or similar processes. Although A&O is perceived to be one of the few firms with the market knowledge and resources to do this specialized work, and, although clients think they receive personalized, high quality advice, both sides think there is an increasing standardization of delivery. This process is called by academics the “industrialization of services”; a completely different business to individual advisory work, needing completely different processes and competencies.

In response to this, the firm has initiated a “More for less strategy”, aimed at delivering service to clients in new ways. It asks: how can A&O deliver more to its clients for less cost and effort using different working practices, processes, technology, document automation, sources of resource and so on?

The leaders think, therefore, that some of the existing services need to be carefully re-engineered, perhaps re-configuring back office processes and the use of technology to improve costs, margin, and client satisfaction.

This industrialization process needs the deployment of new skills and techniques. The practice needs to identify those areas where industrialization is a real phenomenon and ask the following: What technologies and systems are employable here? How can things be designed so that clients and associates can use technology instead of people, systems instead of individual preference or serendipity? Should those services which are already high volume be reconfigured or, perhaps, automated further?

For instance, Allen & Overy announced in 2009 the launch of “CDS deliverability”, a tool, sponsored by its innovation committee,* that offers the CDS market an indicator of deliverability for the growing universe of frequently traded reference obligations. The online service brings greater transparency and efficiency to the credit derivatives markets by providing rigorous legal analysis of deliverability made available in a one-page report for each obligation. (Historically market participants have conducted this analysis on a unilateral basis, duplicating effort and cost without the benefit of a recognized market standard.) CDS deliverability has been developed in association with Markit, a provider of independent data, portfolio valuations, and OTC derivatives trade processing to the global financial markets.

Simon Haddock, head of Allen & Overy’s Derivatives and Structured Finance practice, said: “Quick and efficient mechanisms for delivery of both legal and market data are an integral part of the commoditization of the credit markets. The market has long sought a cost-effective and timely indicator of deliverability for frequently traded obligations. CDS deliverability has been produced to satisfy that demand based on feedback from a number of leading dealers in the credit markets.”

Despite the industrialization forces, though, the partners are firmly of the view that there will always be demand for customized, high quality advice from world class experts. So, in parallel with the cost/efficiency strategy it has created a deliberate programme to maintain “high end work”.

There are several aspects to the programme which involves equipping partners with new skills and adopting different routes into leading clients. To do this, a partner needs to create a new dialogue with its clients, “moving up the value chain”, to discuss emerging legal, regulatory, and risk issues with business leaders, rather than merely taking instructions from in-house legal counsel and deal transactions. In doing so, partners need to adopt “the language of the board room”, learn how to identify latent needs, and maintain positive relations with the general counsel’s team. This will require new approaches, language, and skills.

* Allen & Overy’s innovation committee is a small group of senior partners, with two retained external advisors, which has a mandate and a budget to identify and sponsor innovation across the firm.

![]() RATING: Practical and powerful

RATING: Practical and powerful