![]() RESEARCH

RESEARCH

Application: Client, Competitor, or Market Insight

The Concept

It is difficult to capture the complexity, organizational competence, and variety of technique used in well run and properly commissioned research. This highly specialized field combines managerial competence, agency specialization, acquired professional insight, sophisticated statistical analysis, and hard won insight into markets and/or human behaviour. Where it is done well, it is highly valued. Surprisingly large and well run companies, though, do not invest in research and do not set out to understand or adopt appropriate techniques. Too many either neglect it or try to get insight for bottom dollar prices. Others use it to justify established views; like the proverbial drunk using a lamp post for support rather than illumination.

Field research is familiar not only to marketers but also to many business leaders. They may have seen results of research presented at internal meetings or read many research reports. Unfortunately, familiarity can breed contempt, making the processes, the techniques, and the outcomes seem deceptively simple. As a result, there are many unconvincing or poor research reports resulting from poor specification or poor use of the research industry.

Yet, undertaken properly, field research yields insights into human needs, customer views (which can be different to needs), competitor performance, and market trends. It can reveal the different elements of an offer which customers value and how they combine with different price points to form packages that they will buy. Moreover it can reveal how these vary between different customer groups, creating opportunities through variation of offer in different market segments. It can also save money by stopping new ideas and marketing initiatives which the market will reject. Yet to do all this it has to be properly specified and managed. It needs a brief and a managerial process if it is going to produce results. This needs to ensure that the sample frame, the approach, the technique, and the questionnaires are appropriate.

A typical, well run research process includes the following steps:

(i) Agree objectives and research needs.

(ii) Write brief for agencies. Brief includes:

- Research objectives

- Summary description of the market

- Description of the research problem and desired output

- Description of existing knowledge and previous research

- Budget constraints

- Time scales

- Report requirements

- Constraints (e.g. interviews must be arranged via client relationship managers).

(iii) Shortlist potential agencies.

(iv) Contact and invite to pitch.

(v) Create selection criteria. These might include:

- Technical skills

- Previous experience

- Interpretation of the brief

- Proposed approach

- Team fit (will the firm’s people be able to work with them?)

(vi) Hold presentations by agencies with selection team.

(vii) Choose and confirm agency.

(viii) Negotiate contract.

There are two main types of research. The first is the qualitative or “in depth” approach. This involves spending time with a relatively small number of people and seeking deep answers to questions. It gives colour to views and can reveal underlying feelings and motivations that can be enormously valuable. Quantitative research, on the other hand, involves a wider number of contacts, normally to investigate trends. Both have their strengths and their weaknesses. Companies also tend to reach for two main types of research approaches: ongoing trend surveys and ad hoc research projects. The first involves clear managerial processes to set up and run the research mechanism, especially if it is a specifically commissioned piece of work rather than the purchase of external questions in an established external programme.

However, methods used to collect and analyse research data vary enormously. They range from face-to-face interviews and observed discussion groups to telephone, postal, or internet surveys. For example:

(i) Multivariate techniques

These seem to be the most common approaches in use at the time of writing. They include approaches such as: cluster analysis, factor analysis, and latent analysis. They enable marketers to obtain and analyse complex data sets. Factor analysis, for example, is a tool to reduce a large number of data points to a few understandable trends.

(ii) Conjoint research

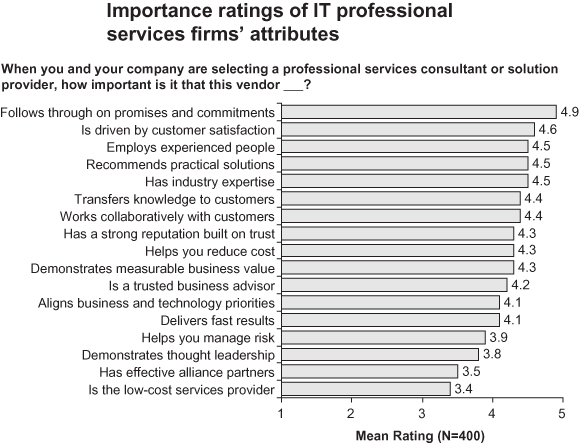

A form of multivariate analysis, this uses questions (either in face-to-face meetings or via email or telephone) designed to trade off different pairs of values or ideas. Figure R.2 shows (with permission) one part of a conjoint study undertaken by America’s “ITSMA”. It demonstrates the richness of data that this technique yields. As interviewees are forced to choose, the approach can mimic the thought processes of customers when considering purchase and can provide powerful insight into new needs and adjustments needed to specific offers. It can also identify potential bundles of features/price mixes for different groups of customers.

Figure R.2: A representation of an actual result of one question in a conjoint survey

(published with the permission of ITSMA)

(iii) “Zones of Tolerance”

Created by Valerie Ziethaml and Mary Jo Bitner (see Ziethaml, V. and Bitner, M. J., 2003) this is a very specific form of conjoint. It differentiates between customers’ “ideal”, “acceptable”, and “unacceptable” tolerances.

(iv) Observational research

As the name suggests this involves a researcher observing the behaviour of people. It can give real insight into human needs and behaviours which are not picked up by other methods because customer views and beliefs are often different to what they actually do. There is, in this particular method, debate about the effect of the observer on the results. It is suggested that it is more objective than, say, interviews, but there is credible evidence that the process of observation, and the observers themselves, influence results.

(v) Explorative research

Sometimes known as deterministic “operational research methods”, this is normally used in developing a new proposition or identifying a new customer segment. It follows issues until a trend suggests that they are likely to be substantive. The work can be iterative, checking back and adjusting the idea as interviewees respond. It is intended to develop initial ideas and insights.

(vi) Concept testing

This involves testing ideas for new propositions or approaches with customers before launch. They are shown an idea or marketing programme and asked to comment on it in a structured way.

(vii) Depth interviews

These are individual conversations with people who represent the sample of customers. They are intended to understand issues in depth and, like other qualitative techniques, cannot be set down too prescriptively. Although interview guides might be agreed it is unlikely that the interviewer will be able to stick to them as issues and ideas surface.

(viii) Focus groups

These are facilitated discussions of groups of people who represent the sample of customers. They ought to be led by an expert and can be observed in a research lab. They give a deeper and more rounded view of a segment’s view than individual conversations because of the interactive conversation.

(ix) Cluster analysis

This is a generic name given to a range of approaches which identify similar groupings and relationships between them. It is particularly good, for example, at finding similar attitudes as part of a good piece of segmentation research; or grouping various price tolerances amongst different customers; or identifying potential market positions. Academics and researchers will understand that there are different types of clustering procedures. The strength of the technique is that it identifies patterns in data which can be easily presented in graphical form; communicating complex data easily. That, though, is perhaps also the weakness of it. Executives might be too quick to jump to conclusions and actions where subtlety and interpretation are needed.

(x) Correspondence analysis

This is a technique which is able to represent “multi-dimensional tables” in digestible form. It is a process by which tables of raw data are related on relevant dimension. The inter-relationships of various results are then plotted in graphical form. It is, again, a powerful way of reducing complex data (like segment needs or competitive brand positions) in easily communicated constructs.

(xi) Various regression analysis techniques

These include things like multiple regression, automatic interaction detection, etc.

(xii) Artificial intelligence

One of the big disappointments in the development of technology is AI. (In the 1960s, it was credible to believe that there would be an operating, conscious computer, like HAL, by “2001”.) Nevertheless, there is experience of trying to use the current AI technology to solve marketing problems. They tend to be the answer to problems needing complex simulations.

(xiii) “Fuzzy sets”

This is a modern mathematical technique used to tackle abstract concepts. As this is deliberately designed to tackle vagueness, it can help with a number of marketing issues around human behaviour and response – if you can get near to understanding it!

(xiv) Simulation

This involves the creation of a model, usually a computer model, which mimics real marketing problems. The approach might help test various marketing strategies which might involve heavy initial investment or help decide between various strategic options. Some of the models used by bankers to assess viable alternatives in markets open to candidates of aggressive acquisition are near to these sorts of simulations.

(xv) Hybrid techniques

These might include: dynamic programming and Heuristic programming.

Clearly the appropriate approach and technique ought to be chosen with an experienced and specialist researcher. One practical way to pull together this complex array of possibilities might be around the pragmatic purposes for which the marketer wants to use research, as indicated in Table R.1 below:

Table R.1 Illustration of the linkage of research purpose to technique

| Purpose | Potential general methods | Potential technique |

| Explore | Focus groups

Depth interviews Observational Ethnographic | Omnibus (say, online)

Phone questionnaires |

| Develop | Sequential recycling

Online labs Deprivation/switching/trial/user experience | Online labs

Conjoint Quali-quant |

| Evaluate | Online concept test

Full potential test Simulated test market (STM) Equity tracking NPS surveys |

Research needs to be used properly and fill a gap in knowledge. It is sensible to first conduct an exhaustive “desk review” to see if an internet search can point to libraries, professional societies, or academic institutions that have already conducted research or provided commentary on the subject in question. In fact, many people in large companies which lack a structured research library find, after a brief search, that their own company has conducted research near to the subject in question on previous occasions.

Once this preliminary work has been completed, the gap in knowledge ought to be clearly defined in a brief to a specialist research agency. This should specify the purpose of the research. It might be to test a new idea, to test segmentation dimensions, to understand a new concept, or to identify client needs. The exercise will be confused if there are too many objectives. In particular, the information yield that is expected must be made clear to the supplier.

Once results come through, careful interpretation is needed. It is important to understand, not only the statistically valid representation of results but also their meaning. Human beings often do not know what they want and, sometimes, why they behave in a particular way. They will say they want cheapness yet spend outrageous sums on branded luxury goods or, in business, on a consultancy project from an elite, branded supplier. So research needs careful commissioning, good execution, and enlightened interpretation. Yet the expense and effort is more than worthwhile. It can lead to profitable new insights that build strong future revenue streams and can obviate mistakes.

History, Context, Criticism, and Development

Companies in America and Europe have been conducting structured research since the start of the 20th century. In 1923, for instance, Robert Woodruff of Coca-Cola expanded the former “Information department” to conduct pioneering market research (see Pendergrast, M., 1993). In 1927, this department studied 15,500 retail outlets over a three-year period to establish that there was a relationship between traffic flow and sales volume. They demonstrated both this and the Pareto effect (a third of outlets accounted for 60% of sales volume). The highest performing outlets were in the best locations but also had few Coca-Cola signs. Sales strategy was revised after the survey (sales people visited four times a year offering special support) and an extensive consumer research project initiated (into 42,000 drug store customers).

There were established market research departments, market research agencies, and marketing consultants who appear to have been a routine part of American business in the 1920s.

It is, perhaps, not surprising, then, that a 1927 American marketing text book (White, P., 1927) talks freely about the “regular market research department” and some of the challenges presented to it by “modern, scientific marketing methods”. As a result of nearly a century of research practice and academic study there is now a vast range of acquired knowledge and practice which is available to modern marketers.

Research is also, of course, used extensively by academics investigating aspects of marketing and sales. Their techniques are usually rigorous and peer-reviewed, mimicking the approach of scientific disciplines. It is sensible for practising marketers to access their work and understand academic studies relevant to their own information needs. It is rare that there is not some study in some part of the world which is close to a developing need and even rarer that an experienced academic is not willing to cooperate with a company in solving a knotty research problem at reasonable prices. Too many neglect this route.

Voices and Further Reading

- “… there will be special research problems to be met and solved. Some of these will come up in the course of routine work, but in general these problems should be organized in some fashion or other, so that the most important ones be undertaken first. Thus the marketing manager may well suggest to the director of research certain pressing problems, or the director of research may submit to the marketing manager the problems which he considers of the greatest importance.” White, P., 1927.

- “Market research has proved a valuable role in assessing incremental improvements but has proved unreliable for radical marketing ideas. Baileys Irish Cream now dominates the global liqueurs market, but when it was introduced in the mid-70’s it had already been rejected in all market research tests. Luckily the Baileys marketers had learned to interpret that as an encouraging sign.” Ambler, T., 2003.

- “One general way to classify consumer research is in terms of the fundamental assumption the researchers make about what they are studying and how to study it … The basic set of assumptions underlying the dominant paradigm at this point in time is positivism … that human reason is supreme and that there is a single, objective truth that can be discovered by science … The newer paradigm is interpretivism … that our society places too much emphasis on science and technology, and that this ordered rational view of consumers denies the complexity of the social and cultural world in which we live.” Solomon, M. et al., 2006.

- “We need to broaden our thinking about understanding consumers beyond the perspective of market research’s conventional wisdom … Understanding consumers is not about data and the superiority of one method over another. The amount of data we collect, or the number of interviews we conduct, is not the critical success factor. Understanding consumers is about creating explanations that can be inspired by data but equally well come from experience and intuition.” “Understanding consumers” by Calder, B.J. in Iacobucci, D., Kellogg on Marketing, 2001.

- Sherry, J. and Kozinets, R.V., “Qualitative inquiry in marketing and consumer research in Iacobucci, D. (ed.), Kellogg on Marketing. 2001.

- Moutinho, Luiz, “Quantitative methods in marketing” in Baker, M.J. and Hart, S. (eds), The Marketing Book. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2008.

Things You Might Like to Consider

(i) Field research ought to carry an arrogance warning. Managers and leaders in all sectors of industry can be very dismissive of it. Many have been heard to remark that there is little that field research can tell them about their buyers. Yet they are almost always wrong. In fact, some very senior business leaders have been chastened by the direct comments they have heard their buyers make when sitting behind two-way mirrors watching focus groups.

(ii) There are numerous examples of mistakes due to poor interpretation, as shown by the inability to see latent markets (see the market maturity section).

(iii) Customers often do not know what they want. Poorly designed research will not uncover latent needs that they are unaware of.

(iv) Research has its limitations. Some companies have found innovation and new offers through explorative interaction with their customers rather than field research. Sometimes, a visionary creates a market by intuitively understanding latent need. Hence Henry Ford’s famous comment that, if he had asked people what they wanted, they would have asked for faster horses.

(v) This is as much about developing organizational competence as any other part of marketing. Marketers ought to set up processes which contribute to progressive organizational learning in research methods.

(vi) There is evidence that, even in the most market-orientated companies sclerosis can damage the potential yield from field research. At the time of writing, for instance, some specialists in large research departments are unduly sceptical of behavioural economics and its implications whilst agencies report that a number of large product companies have become so bound up in process that creative insight and interpretation of opportunity have been lost or outsourced.

(vii) Filed research can give marketers political power. Properly conducted and communicated, it can give direction to other functions and their work. Few are able to challenge that the work represents customer views and should be taken seriously. It can be used to influence the priorities of other functions toward market need.

![]() RATING: Practical and powerful

RATING: Practical and powerful