![]() SEGMENTATION

SEGMENTATION

Application: Strategy, Communication, Positioning, NSD/NPD

The Concept

The segmentation of markets into groups of buyers which can be easily reached by suppliers is a powerful concept which has improved the profit of many businesses. It suggests that buyers can be grouped around common needs. Then, by customizing the firm’s offer to meet those common needs, suppliers can both gain competitive advantage and save costs because they are only addressing a portion of the market. Customer segmentation is one of the fundamental building blocks of marketing. It is the basis of: effective marketing communication, innovative offers, and appealing brands. The human insight which follows from deep knowledge of a group of human beings is the source of real competitive advantage. Segmentation, to some extent, is marketing.

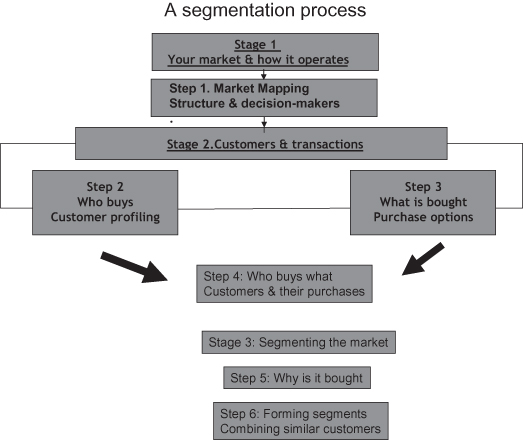

There appear to be few developed and well accepted approaches to producing effective segmentation. Some advertising agencies arrive at it through creative insight, more logical minds through a review of patterns in data, while others observe and analyse behaviours. The process shown in Figure S.1 was published by Professor Malcolm McDonald (McDonald, M.H.B., 1998). In a very practical book he argued that marketers should first define and map their generic market. They should then take an objective view of the customers and their buying behaviour before doing detailed research.

Figure S.1: A suggested segmentation process

Experience suggests that marketers should approach this with an idea of how they think their market might segment; with an hypothesis. They will need to think about how customers behave and discuss different attitudes or behaviours that they have observed. Eventually they will reach an hypothesis which can be tested. The marketer should then create a set of “segmentation dimensions” by which these differences will manifest themselves. Segmentation dimensions are the ways in which the buyers will behave towards the firm and its offers. As far as possible, they should be values, beliefs, or cultural biases (whether amongst consumers or organizations) because they determine behaviour. These can then be scaled using sensible scoring of the extremes. For example, if a supplier was segmenting a business-to-business market on the basis of “organization style”, they might hypothesize that there are centralized and de-centralized organizations. This would manifest itself in different business practices, one of which would be purchasing style and this would become a segmentation dimension. For a centralized organization, buying would be controlled by a central purchasing department, whereas in a de-centralized organization it would be devolved to business units. If the segmentation is effective, each group will exhibit these in different ways.

The hypothesis can first be tested by examining any existing customers and scoring their behaviour against segmentation dimensions. It should be possible to conduct a fast, inexpensive test on the validity of the dimensions, where different clusters appear. If no clustering is apparent in this first test, then new dimensions, or maybe a new hypothesis, need to be created. Any clustering should be confirmed with direct research. This is best conducted in two phases: first, a qualitative phase, testing the dimension in depth with a few potential customers; secondly, a large quantitative project using a trade-off technique such as conjoint research. Through this method different clusters of potential buyer groups will become evident. Again, if clustering does not appear the marketer should revisit the initial hypothesis. However, research itself is not really sufficient to confirm such an important phenomenon as customer segmentation. Potential segments should also be confirmed in a more practical way, imitating as far as possible the rough and tumble of the real market place. A number of test marketing programmes should be designed in order to ensure that the buyers identify with the proposed groups that they are in and respond to propositions specifically designed for them.

Marketers should then create a full investment and marketing implementation plan. Segmentation has implications to: the market proposition for each group, the ideal method of marketing communication, sales strategy, IT systems, operational processes, pricing, and the most appropriate customer service methods for each group. Taken seriously, it affects every aspect of the way the firm approaches its intended market. Each aspect needs to be carefully thought through, costed, and built into all the operational plans of the business. This needs to be treated like any other hard-headed investment strategy. The pros and cons, benefits, and return on investment need to be assessed and drawn together into an investment plan, which should be submitted to the appropriate leadership team for formal approval. As part of implementation of the plan, everyone in the organization will eventually need to be familiar with the new segments and how they should be handled.

Clear tests have been developed to check whether a particular segmentation is appropriate for a particular company in a particular market. They include:

- Homogeneity: To what extent will the members of the segment act in the same way?

- Measurability: How big and valuable is the segment?

- Accessibility: Is it possible to reach the segment with marketing or sales programmes?

- Profitability: Is the segment substantial enough for the supplier to profit from?

- Attractiveness or relevance: Is the segment something customers will want to identify with?

History, Context Criticism, and Development

There have been several methods of consumer segmentation developed and publicized over the past decades. They include:

Demographics and socioeconomics: The grouping of people according to physical characteristics (age, sex) or circumstances (income, occupation, or education). This is commonly used in developed nations. In the US and Europe, for example, there is currently much emphasis on the design of products and services for ageing populations.

Life stage: This is a more precise form of demographics. It groups buyers according to the phase they have reached in their life such as “married”, “home building”, or “retired”. They might become “freedom seekers”, “dropouts”, or “traditionalists” according to their phase of life.

Psychographics: The grouping of people according to various personal characteristics such as personality or social class. In the 1980s, for instance, the “British National Readership Survey” categorized the population as “A” (higher managerial), “B” (middle class), “C” (lower middle class), and “D” (working class). However, this has now broken down.

Geographic/location: Grouping people according to their country of birth or area of residence. This can focus on the region, population density, and climate. It can involve county, town, or even street.

Behavioural or attitudinal: Grouping according to a particular behaviour which may affect product usage or price sensitivity, or values and attitudes. A good example was created by the marketing agency McCann-Erickson in the latter half of the 20th century. It identified: “avant guardians” (concerned with change and well being), “pontificators” (who have strongly held traditional views), and “self-exploiters” (who have high self-esteem).

“Tribal”: A specific example of behavioural segmentation which groups customers according to the social groups or cultures with which they identify. For example, in the 1990s, one of Europe’s premier television companies, the BBC, started to commission programmes for tribes in society (such as young, independent women) based on how they communicate and live.

Benefits sought: The grouping of people according to the advantages they are seeking from the product or service. For instance, as early as 1968, Russell Haley (Haley, R.I., 1968) published segmentation for the toothpaste market based on this approach. Customers were in the “sensory” segment (seeking flavour or product appearance) or the “sociable” segment (seeking brightness of teeth), or the “worriers” (seeking decay prevention).

Lifestyle: Grouping customers by a common approach to life. One famous example of this type of segmentation was developed by Young & Rubican in the 1980s. It was this advertising agency which developed, among others, the famous, but now defunct term, “Yuppie” (Young Urban Professional). Incidentally, this also illustrates an important point about customer segmentation: it dates easily. Whereas people revelled in being a Yuppie in the early 1980s, it is now considered out-of-date and unattractive.

Context: Proposed by Professor Paul Fifield in the early 1990s (Fifield, P., 1992), this method groups customers according to the context in which they use a product or service. It focuses attention on things that bring people together, exploiting shared interests. For instance, one cursory glance at people on a fishing bank will show that they have little in common other than the sport itself.

Business-to-business segmentation types have included:

Industry sector: Grouping businesses according to the industry in which they specialize. These sectors are often formally set by government economists as a means of defining and recording activities in different areas of the economy (see sector marketing).

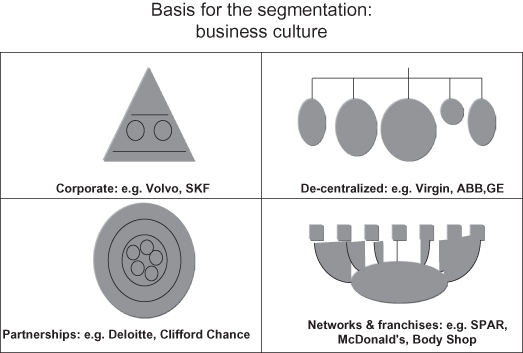

Organization style: Grouping businesses according to the culture or prevailing climate of the company. They may be centralized or de-centralized or “innovative” versus “conservative”. The Myers Briggs organizational types (“fraternal”, “collegial”, “bureaucratic”, or “entrepreneurial”) have, for example, been used as a basis for segmentation;

Organizational size: Grouping businesses according to the number of employees, assets, or revenue.

Organizational structure: Grouping businesses according to the way they choose to organize and structure their company. There are significant differences (as illustrated in Figure S.2) which can be used to create effective segmentation programmes.

Figure S.2: An hypothesis for business-to-business segmentation based on organizational style

Company life cycle: Companies, like product groups, seem to have “life cycles” through which they evolve. They go from birth to death at different rates, struggling to get through “inflection points” to increase revenue and margin. They have similar characteristics (e.g. management style) in each phase and this has been used as a basis for segmentation.

Industry maturity: Industries and markets also move through different phases (see market maturity). For instance, in developed economies, their agricultural or manufacturing industries are at a different phase of evolution to, say, biotechnology. The phase of growth affects the behaviour of suppliers in it and has also been used as a basis for segmentation.

Context: As with consumers, grouping businesses according to the context in which they use the product or service.

Needs-/benefits-based: Based on underlying needs or benefits sought by the company from its suppliers.

Voices and Further Reading

- McDonald, M.H.B. and Dunbar, I., Market Segmentation: How to Do it, How to Profit from it. MacMillan, 1998.

- “Segmentation is a creative and iterative process, the purpose of which is to satisfy customer needs more closely and, in so doing, create competitive advantage for the company. It is defined by customers’ needs and requirements, not the company’s, and should be revisited periodically. The importance of segmentation to any business should not be underestimated.” McDonald and Dunbar, ibid.

- “Segmentation variables can be broadly classified into two categories: identifier and response. Identifier variables begin by segmenting the market based on who the customers are … in contrast, post hoc segmentation starts by using response variables to divide the market on the basis of how customers behave.” Kumar, N., 2004.

- “Segmentation is a critical aspect of corporate strategy. It is essential in visualizing the competitive arena and analyzing the preferred strategic emphasis. The goal is to find a way to convert differences from competitors into a cost differential that can be maintained.” Stern, L. in The Boston Consulting Group on Strategy. John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2006.

- “Whether within or across national boundaries, effective market segmentation delineates segments whose members are similar to one another in one or more characteristics and different from other segments.” Solomon, M. et al., 2006.

- Sternthal, B. and Tybout, A.M., “Segmentation and targeting” in Iacobucci, D. (ed.), Kellogg on Marketing. 2001.

Things You Might Like to Consider

(i) There are many ways to segment any one market. Like a Rubik’s cube, the marketer needs to find their own effective segmentation for their own unique position in their market.

(ii) It is professionally wrong and very limiting to regard products as segments. There is no such thing as a “big systems market” or the “executive car market”. There are human beings who buy these things and they have a multiplicity of different needs, wants, and aspirations.

(iii) People have a herd instinct and can identify with a segment. If the target group can be expanded by people who aspire to belong, demand for the proposition will be increased.

(iv) In the past few decades, marketing thinkers have begun to emphasize the “market of one” and mass customization. It is argued that companies need to respond to each individual need. Whilst Amazon has been able to create and deploy technology which is able to take this approach, many have not. There is little evidence that people are ceasing to follow trends and behave without group mentality, so, at the time of writing, the segmentation concept does not yet seem to be debunked.

![]() RATING: Practical and powerful

RATING: Practical and powerful